Don’t raise issues for the first time before the CAFC unless it falls into one of the limited exceptions: the CAFC affirms the stylized letter “H” mark to be confusingly similar

| September 3, 2019

Hylete LLC v. Hybrid Athletics, LLC

August 1, 2019

Moore, Reyna, Wallach (Opinion by Reyna)

Summary

On appeal, Hylete LLC (“Hylete”) argued, for the first time, that the Board erred in its analysis by failing to compare its stylized “H” mark with “composite common law mark” of the Hybrid Athletics, LLC (“Hybrid”), comprising of the stylized letter “H” appearing above the phrase “Hybrid Athletics” and several dots underneath. By not presenting the argument during the opposition proceedings or at the request for reconsideration, the CAFC held that Hylete waived its argument, and upheld the decision of the Board.

Details

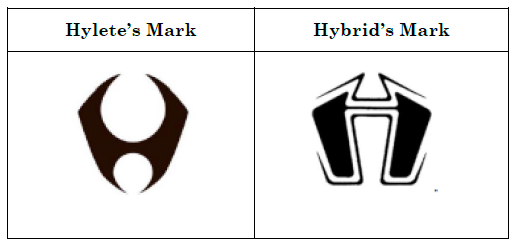

Hylete LLC applied to register a design mark for a stylized letter “H” in International Class 25 for “[a]thletic apparel, namely, shirts, pants, shorts, jackets, footwear, hats and caps.” Upon examination, the mark was approved for publication, and the mark published for opposition in the Trademark Official Gazette on June 18, 2013. After filing an extension of time to oppose, on October 16, 2013, Hybrid Athletics, LLC filed a Notice of Opposition on the grounds of likelihood of confusion with its mark under Section 2(d) of the Lanham Act. Hylete and Hybrid’s marks are as shown below:

Hybrid pleaded ownership in Application No. 86/000,809 for its design mark of a stylized “H” in connection with “conducting fitness classes; health club services, namely, providing instruction and equipment in the field of physical exercise; personal fitness training services and consultancy; physical fitness instruction” in International Class 41. Hybrid also pleaded common law rights arising from its use of the mark on “athletic apparel, including shirts, hats, shorts and socks” since August 1, 2008. The following images were submitted by Hybrid as evidence to show the use of the mark on athletic apparel:

All of the images showed the stylized “H” mark appearing above the phrase “Hybrid Athletics” and several dots underneath the phrase.

Hylete’s argument before the Board focused on the two stylized “H” designs having a different appearance, with each mark having its own distinct commercial impression. On December 15, 2016, the Board issued a final decision, sustaining Hybrid’s opposition, concluding that Hylete’s mark is likely to cause confusion with Hybrid’s mark. Hylete filed a request for reconsideration of the Board’s final decision, including an argument that “[t]here was no record evidence demonstrating that consumers would view [Hylete’s] mark as a stylized H” as a part of its commercial impression argument. The Board found that this argument is contrary to Hylete’s own characterization of the mark in its brief, as well as the testimony of its CEO, which admitted that both logos were Hs. The Board rejected Hylete’s argument and denied the request for rehearing. Hylete appealed the decision of the Board to the CAFC.

On appeal, Hylete argued that the Board erred in its analysis by failing to compare Hylete’s stylized “H” mark with Hybrid’s “composite common law mark,” comprising of the stylized letter “H” appearing above the phrase “Hybrid Athletics” and several dots underneath, as shown below:

In its appeal brief, Hylete stated as follows: “this appeal may be summarized into a single question: is Hylete’s mark sufficiently similar to [Hybrid’s] composite common law mark to be likely to cause confusion on the part of the ordinary consumer as to the source of the clothing items sold under those marks?”

In response, Hybrid stated that the “composite common law mark” arguments were never raised before the Board and are therefore waived.

The CAFC considers arguments made for the first time on appeal under the following limited circumstances:

- When new legislation is passed while an appeal is pending;

- When there is a change in the jurisprudence of the reviewing court or the Supreme Court after consideration of the case by the lower court;

- Even if the parties did not argue and the court below did not decide, when appellate court applies the correct law, if an issue is properly before the court; and

- Where a party appeared pro se.

Hylete did not dispute that the argument was not raised before the Board. Instead, Hylete contended that the argument has not been waived, because the Board “sua sponte” raised the issue of Hybrid’s common law rights in its final decision. The CAFC disagreed, stating that Hylete’s failure to raise the argument in the request for reconsideration negates its contention.

As Hylete could have raised the issue of Hybrid’s “composite common law mark” in the opposition proceedings or in the request for reconsideration, but did not do so, and as none of the exceptional circumstances in which the CAFC considers arguments made for the first time on appeals applies, the CAFC held that the issues raised by Hylete on appeal have been waived.

As the only issues Hylete raised on appeal concerned Hybrid’s “composite common law mark,” the CAFC affirmed the decision of the Board.

Takeaway

- Raise all possible arguments prior to appeal.

- It seems that the record before the Board lacked evidence that the letter H is conceptually weak or diluted in the context of the goods or in general – perhaps more evidence before the Board would have helped Hylete in this case. At the same time, perhaps presenting such evidence is not desirable to Hylete, as that would be an admission that its own mark is weak.

Arguments of “as a whole”, “high level of abstraction,” “novelty/nonobviousness,” “physicality” and “machine-or-transformation test” for subject matter eligibility were successful at the PTAB and the district court, but not at the Federal Circuit

| August 30, 2019

Solutran, Inc. v. Elavon, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2019) (Case Nos. 2019-1345, 2019-1460)

July 30, 2019

Chen, Hughes, and Stoll, Circuit Judges. Court opinion by Chen.

Summary

The Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s denial of summary judgment of ineligibility regarding a patented claims titled “system and method for processing checks and check transactions,” by concluding that the asserted claims are not directed to patent-eligible subject matter under § 101 because, under the Alice two-step framework, the claims recited the abstract idea of using data from a check to credit a merchant’s account before scanning the check, and because the claims do not contain an inventive concept sufficient to transform this abstract idea into a patent-eligible application.

Details

I. background

1. The Patent

Solutran, Inc. (Solutran) owns U.S. Patent No. 8,311,945 (’945 patent), titled “System and method for processing checks and check transactions.” The proffered benefits include “improved funds availability” for merchants and allegedly “reliev[ing merchants] of the task, cost, and risk of scanning and destroying the paper checks themselves, relying instead on a secure, high-volume scanning operation to obtain digital images of the checks.” ’945 patent at col. 3, ll. 46–62.

Claim 1, the representative claim of the ’945 patent, recites as follows:

1. A method for processing paper checks, comprising:

a) electronically receiving a data file containing data captured at a merchant’s point of purchase, said data including an amount of a transaction associated with MICR [(Magnetic Ink Character Recognition)] information for each paper check, and said data file not including images of said checks;

b) after step a), crediting an account for the merchant;

c) after step b), receiving said paper checks and scanning said checks with a digital image scanner thereby creating digital images of said checks and, for each said check, associating said digital image with said check’s MICR information; and

d) comparing by a computer said digital images, with said data in the data file to find matches.

2. The Alice Two-Step Framework under 35 U.S.C. § 101

To determine whether a patent claims ineligible subject matter, the U.S. Supreme Court has established a two-step framework. In Step One, courts must determine whether the claims at issue are directed to a patent-ineligible concept such as an abstract idea. Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank International, 573 U.S. 208, 217 (2014). In Step Two, if the claims are directed to an abstract idea, the courts must “consider the elements of each claim both individually and ‘as an ordered combination’ to determine whether the additional elements ‘transform the nature of the claim’ into a patent-eligible application.” Id. To transform an abstract idea into a patent-eligible application, the claims must do “more than simply stat[e] the abstract idea while adding the words ‘apply it.’” Id. at 221. At each step, the claims are considered as a whole. See id. at 218 n.3, 225.

3. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB)

Two months after the Supreme Court issued the decision in Alice, the PTAB issued an institution decision granting a petition of a covered business method (CBM) review by U.S. Bancorp as to the § 103 challenge (obviousness) but denying a petition as to the § 101 challenge (lack of subject matter eligibility), concluding that claim 1 of the ’945 patent was not directed to an abstract idea. U.S. Bancorp v. Solutran, Inc., No. CBM2014-00076, 2014 WL 3943913 (P.T.A.B. Aug. 7, 2014). The PTAB reasoned that “the basic, core concept of independent claim 1 is a method of processing paper checks, which is more akin to a physical process than an abstract idea.” Id. at *8. It is noted that the CBM post-grant review certificate was issued under 35 U.S.C. § 328(b) on February 14, 2018, reflecting the final results of CBM2014-00076 determining that claims 1-6 are found patentable.

3. The District Court

Solutran sued U.S. Bancorp and its affiliate Elavon, Inc. (collectively, U.S. Bank) in the United States District Court for the District of Minnesota, alleging infringement of claims 1-5 of the ’945 patent. U.S. Bank moved for summary judgment that the ’945 patent was invalid because the claims were directed to the “abstract idea of delaying and outsourcing the scanning of paper checks.”

On February 23, 2018, the district court entered summary judgment for Solutran finding that the ‘945 patent was patent eligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101 for following reasons:

· Step One: The district court found the previous CBM review of the ’945 patent by the PTAB persuasive, concluding that that the ’945 patent is directed to an improved technique for processing and transporting physical checks, rather than just handling data that had been scanned from the checks.

· Step Two: The district court concluded, in the alternative, that the asserted claims also recited an inventive concept under step two of Alice. The district court accepted Solutran’s assertion that “Claim 1’s elements describe a new combination of steps, in an ordered sequence, that was never found before in the prior art and has been found to be a nonobvious improvement over the prior art by both the USPTO examiner and the PTAB’s three-judge panel.” The district court also concluded that the claim passes the machine-or-transformation test because “the physical paper check is transformed into a different state or thing, namely into a digital image.”

U.S. Bank appeals, inter alia, the § 101 ruling. Solutran cross-appeals on the issue of willful infringement.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit reversed the summary judgment in favor of Solutran on the issue of the subject matter eligibility, concluding that, contrary to the views of the PTAB and the district court, the claims are not directed to patent-eligible subject matter under § 101 because the claims of the ’945 patent recite the abstract idea of using data from a check to credit a merchant’s account before scanning the check, and because the claims do not contain an inventive concept sufficient to transform this abstract idea into a patent-eligible application. The Federal Circuit thus did not review U.S. Bank’s alternative § 103 argument or Solutran’s cross-appeal relating to a potential willful infringement claim.

The unanimous court opinion by Circuit Judge Chen discussed each step of the two-step framework in detail.

1. Step One

The Federal Circuit concluded that the claims are directed to the abstract idea of crediting a merchant’s account as early as possible while electronically processing a check.

Comparison with Precedents

The Federal Circuit has a precedent as to the determination of “abstract idea” that the court finds it sufficient to compare claims at issue to those claims already found to be directed to an abstract idea in previous cases, instead of establishing a definitive rule to determine what constitutes an “abstract idea.” Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., 822 F.3d 1327, 1334 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

The court opinion argued that “[a]side from the timing of the account crediting step, the ’945 patent claims recite elements similar to those in Content Extraction & Transmission LLC v. Wells Fargo Bank, National Ass’n, 776 F.3d 1343 (Fed. Cir. 2014)” where the Federal Circuit held that a method of extracting and then processing information from hard copy documents, including paper checks, was drawn to the abstract idea of collecting data, recognizing certain data within the collected data set, and storing that recognized data in a memory. As for the account crediting step, the court opinion stated that “[c]rediting a merchant’s account as early as possible while electronically processing a check is a concept similar to those determined to be abstract by the Supreme Court in Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593 (2010) and Alice.”

In sum, the court opinion concluded that the claims at issue are similar to those claims already found to be directed to an abstract idea in previous cases.

As A Whole

Solutran argued that the claims “as a whole” are not directed to an abstract idea. The court opinion countered by pointing out that “[t]he only advance recited in the asserted claims is crediting the merchant’s account before the paper check is scanned,” and concluded that this is an abstract idea.

The court opinion distinguished this case from previous cases where claims were held patent-eligible by noting that this is not “a situation where the claims “are directed to a specific improvement to the way computers operate” and therefore not directed to an abstract idea, as in cases such as Enfish,” nor is it “a situation where the claims are “limited to rules with specific characteristics” to create a technical effect and therefore not directed to an abstract idea, as in McRO, Inc. v. Bandai Namco Games America Inc., 837 F.3d 1299, 1313 (Fed. Cir. 2016).” The court opinion further stated that “[t]o the contrary, the claims are written at a distinctly high level of generality.”

High Level of Abstraction

The court opinion disagreed with Solutran that U.S. Bank “improperly construe[d] Claim 1 to ‘a high level of abstraction.’” While conceding that “all inventions at some level embody, use, reflect, rest upon, or apply laws of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract ideas,” Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., Inc., 566 U.S. 66, 70, 71 (2012), the court opinion stressed “where, as here, the abstract idea tracks the claim language and accurately captures what the patent asserts to be the “focus of the claimed advance over the prior art,” Affinity Labs of Texas, LLC v. DIRECTV, LLC, 838 F.3d 1253, 1257 (Fed. Cir. 2016), characterizing the claim as being directed to an abstract idea is appropriate.”

Physicality of The Paper Checks Being Processed and Transported

The court opinion concluded that “the physicality of the paper checks being processed and transported is not by itself enough to exempt the claims from being directed to an abstract idea” by citing a precedent that “the abstract idea exception does not turn solely on whether the claimed invention comprises physical versus mental steps,” In re Marco Guldenaar Holding B.V., 911 F.3d 1157, 1161 (Fed. Cir. 2018),

2. Step Two

The court opinion disagreed with the district court’s holding that the ’945 patent claims “contain a sufficiently transformative inventive concept so as to be patent eligible.”

As A Whole

The court opinion stated that “[e]ven when viewed as a whole, these claims “do not, for example, purport to improve the functioning of the computer itself” or “effect an improvement in any other technology or technical field” and that “[t]o the contrary, as the claims in [Ultramercial, Inc. v. Hulu, LLC, 772 F.3d 709 (Fed. Cir. 2014)] did, the claims of the ’945 patent “simply instruct the practitioner to implement the abstract idea with routine, conventional activity.”” The court opinion further found any remaining elements in the claims, including use of a scanner and computer and “routine data-gathering steps” (i.e., receipt of the data file), as “hav[ing] been deemed insufficient by this court in the past to constitute an inventive concept” in the past precedents. Content Extraction, 776 F.3d at 1349 (conventional use of computers and scanners); OIP Techs., Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc., 788 F.3d 1359, 1363 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (routine data- gathering steps).

Novelty/Nonobviousness

In rejecting Solutran’s argument that these claims are patent-eligible because they are allegedly novel and nonobvious, the court opinion reiterated the precedent that “merely reciting an abstract idea by itself in a claim—even if the idea is novel and non-obvious—is not enough to save it from ineligibility.” See, e.g., Synopsys, Inc. v. Mentor Graphics Corp., 839 F.3d 1138, 1151 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (“[A] claim for a new abstract idea is still an abstract idea.” (emphasis in original)).”

Machine-or-Transformation Test

In rejecting Solutran’s argument that its claims passed the machine-or-transformation test—i.e., “transformation and reduction of an article ‘to a different state or thing,’” the court opinion stated “[w]hile the Supreme Court has explained that the machine-or-trans- formation test can provide a “useful clue” in the second step of Alice, passing the test alone is insufficient to overcome Solutran’s above-described failings under step two. See DDR Holdings, LLC v. Hotels.com, L.P., 773 F.3d 1245, 1256 (Fed. Cir. 2014) (“[I]n Mayo, the Supreme Court emphasized that satisfying the machine-or-transformation test, by itself, is not sufficient to render a claim patent-eligible, as not all transformations or machine implementations infuse an otherwise ineligible claim with an ‘inventive concept.’”).”

Takeaway

· The case demonstrates that courts still stick to the comparative approach in Alice step one, instead of defining or categorizing the “abstract idea.” This approach is notably in contrast with that of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, which follows the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance on January 7, 2019, dividing Alice step one into two inquiries: (i) evaluate whether the claim recites a judicial exception; and (ii) evaluate whether the judicial exception is integrated into a practical application if the claim recites a judicial exception. The courts’ approach may give wider latitude to turn an issue of the subject matter eligibility in either direction for its less clarity of the standard.

· Physicality of subjects recited in a claim, novelty/nonobviousness of the claim, and passing of the machine-or-transformation test may not be enough to exempt the claim from being directed to an abstract idea.

“Built Tough”: Ford’s Design Patents Survive Creative Attacks by Accused Infringers

| August 21, 2019

Automotive Body Parts Association v. Ford Global Technologies, LLC

July 23, 2019

Before Hughes, Schall, and Stoll

Summary

The Federal Circuit is asked to decide two questions: what types of functionality invalidate a design patent, and whether the same rules of patent exhaustion and repair rights that apply to utility patents ought to also be applied to design patents. On the former, the Federal Circuit decides that “mechanical or utilitarian” functionality, rather than “aesthetic functionality”, invalidates a design patent. On the latter, however unique design patents are from utility patents, the Federal Circuit declines to apply the well-established rules of patent exhaustion and right to repairs differently between design and utility patents.

Details

Ford Motor Company introduced the F-150 pickup trucks in the 1970’s, and the trucks have become a mainstay of Ford’s lineup. The trucks’ popularity has endured, as the model is now in its thirteenth generation, with Ford claiming to have sold more than 1 million F-150 trucks in 2018.

Ford Global Technologies, LLC (“Ford”) is a subsidiary of Ford Motor Company, and manages the parent company’s intellectual property. Ford’s large patent portfolio includes numerous design patents covering different design elements of Ford vehicles. Among those design patents are U.S. Design Patent Nos. D489,299 and D501,685.

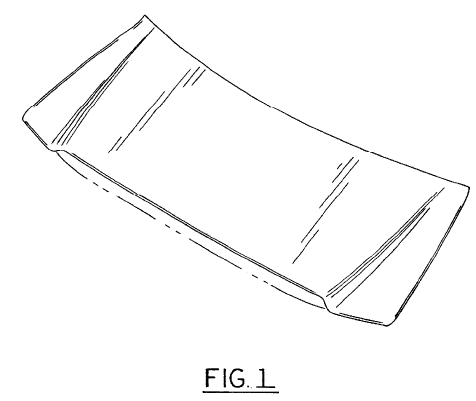

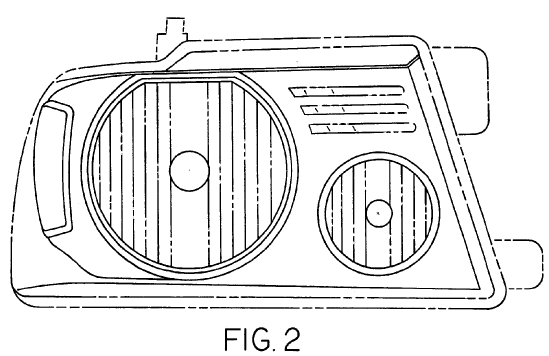

The D’299 patent is directed to an “exterior vehicle hood” having the following design:

The D’685 patent is directed to a “vehicle head lamp” having the following design:

The patented designs are found on the eleventh generation F-150 trucks, which were in production from 2004 to 2008:

Automotive Body Parts Association (“Automotive Body”) is an association of companies that distribute automotive body parts. The member companies serve predominantly the collision repair industry, selling replacement auto parts to collision repair shops or directly to vehicle owners.

Ford began asserting the D’299 and D’685 patents against Automotive Body in 2005, when Ford initiated a patent infringement action in the International Trade Commission. The ITC action was ultimately settled, followed by a few years of relative quiet until 2013, when tension grew after a member of Automotive Body began selling replacement parts covered by Ford’s two design patents.

In 2013, Automotive Body, together with the member company, initiated a declaratory judgment action in a district court, seeking to have the D’299 and D’685 patents declared invalid, or if valid, unenforceable. Automotive Body moved the district court for summary judgment of invalidity and unenforceability, but was denied. Automotive Body’s appeal of that denial of summary judgment leads us to this decision by the Federal Circuit.

Automotive Body’s arguments on appeal mirror those made in the district court.

- Invalidity

Automotive Body makes two main invalidity arguments. First, the designs of Ford’s two patents are “dictated by function”, and second, the two designs are not a “matter of concern”.

The “dictated by function” argument involves a basic design patent concept: if an article has to be designed a certain way for the article to function, then the design cannot be the subject of a design patent.

Design patents protect only “new, original and ornamental design[s] for an article of manufacture”. 35 U.S.C. 171(a). To be “ornamental”, a particular design must not be essential to the use of the article.

Automotive Body argues, rather creatively, that the designs of Ford’s headlamp and hood are functionally dictated not only by the physical fit on a F-150 truck, but also by the aesthetics of the surrounding body parts. Automotive Body’s position is that these commercial requirements for aesthetic continuity, driven by customer preferences, render Ford’s designs functional.

The Federal Circuit disagrees:

We hold that, even in this context of a consumer preference for a particular design to match other parts of a whole, the aesthetic appeal of a design to consumers is inadequate to render that design functional…If customers prefer the “peculiar or distinctive appearance” of Ford’s designs over that of other designs that perform the same mechanical or utilitarian functions, that is exactly the type of market advantage “manifestly contemplate[d]” by Congress in the laws authorizing design patents.

In other words, functionality that invalidates a design should be “mechanical or utilitarian”, and not aesthetical.

Particularly damaging to Automotive Body’s argument is Ford’s abundant evidence of “performance parts”, that is, alternative headlamp and hood designs that would also fit the F-150 trucks. As the Federal Circuit explains, “the existence of ‘several ways to achieve the function of an article of manufacture,’ though not dispositive, increases the likelihood that a design serves a primarily ornamental purpose.”

To bolster its functionality argument, Automotive Body attempts to borrow the doctrine of “aesthetic functionality” from trademark law.

Under that doctrine, trademark protection is unavailable to features that serve an aesthetic function that is independent and distinct from the function of source identification. For example, “John Deere green”, the color, may invoke an immediate association with John Deere, the brand, but the color itself also serves the significant nontrademark function of color-matching many farm equipment. As such, the color is not entitled to trademark protection.[1]

The Federal Circuit quickly disposes of Automotive Body’s “aesthetic functionality” argument, finding that the doctrine rooted in trademark law does not apply to patent law. The competitive considerations driving the “aesthetic functionality” doctrine of trademark law do not apply to the anticompetitive effects of design patents.

Automotive Body’s second invalidity argument is that the designs of Ford’s two patents are not a “matter of concern”.

The “matter of concern” argument involves the straightforward concept that, if no one cares about a particular design, then that design is not deserving of patent protection. Automotive Body argues that Ford’s patented headlamp and hood designs are not a “matter of concern”, because an F-150 owner in need of a replacement headlamp or hood would assess the replacement part simply for their aesthetic compatibility with the truck.

The Federal Circuit finds two faults with Automotive Body’s arguments. First, that an F-150 owner would assess the aesthetic of a headlamp or hood design means that, by definition, the designs are a matter of concern. Second, Automotive Body errs in temporally limiting the “matter of concern” inquiry to when a consumer is purchasing a replacement part. The proper inquiry is “whether at some point in the life of the article an occasion (or occasions) arises when the appearance of the article becomes a ‘matter of concern’”.

- Unenforceability

Automotive Body’s unenforceability arguments are also two-fold.

First, Automotive Body argues that under the doctrine of patent exhaustion, the authorized sale of an F-150 truck exhausts all design patents embodied in the truck. This exhaustion therefore permits the use of Ford’s designs on replacement parts intended for use with the truck.

The Federal Circuit disagrees that the doctrine of patent exhaustion should be so broadly applied.

The doctrine of patent exhaustion is triggered only if the sale is authorized, and conveys only with the article sold. Since Ford has not authorized Automotive Body’s sales of replacement headlamps and hood, and Automotive Body is not a purchaser of Ford’s F-150 trucks, the Federal Circuit easily concludes that Automotive Body cannot rely on patent exhaustion as a defense.

Automotive Body’s second argument is that an authorized sale of the F-150 truck also conveys to the owner the right to repair, so that the owner of the F-150 truck would be permitted to replace the headlamps or hood on the truck.

Here also, the Federal Circuit disagrees with Automotive Body’s broad application of the right to repair.

The right to repair allows an owner to repair the patented headlamps or hood on the truck, but does not allow the owner to make new copies of the patented designs.

A common premise of Automotive Body’s unenforceability arguments is their broad interpretation of the term “article of manufacture” as used in the statute. From Automotive Body’s perspective, the term includes not only the patented component, but also the larger product incorporating that component. By this interpretation, the sale of either the patented headlamps or hood, or the truck containing the patented headlamps or hood would totally exhaust Ford’s rights in the design patents.

The Federal Circuit rejects Automotive Body’s broad interpretation:

In our view, the breadth of the term “article of manufacture” simply means that Ford could properly have claimed its designs as applied to the entire F-150 or as applied to the hood and headlamp… Unfortunately for ABPA, Ford did not do so; the designs for Ford’s hood and headlamp are covered by distinct patents, and to make and use those designs without Ford’s authorization is to infringe.

Had Ford’s design patents covered the whole F-150 truck, the sale of the truck would have exhausted Ford’s rights in those patents. But, as it were, Ford’s patents cover only the designs of the headlamps and the hood, and not the design for the truck as a whole. As such, while the authorized sale of an F-150 truck permits the owner to use and repair the headlamps and the hood, the sale leaves untouched Ford’s ability to prevent the owner from making new copies of those designs.

It is not uncommon for aftermarket suppliers, especially those who supply parts intended to restore a vehicle to its original condition and aesthetics, to promise identity or near identity between its products and the OEM parts. This promise, however, would effectively be an admission that the products infringe any design patents covering the part. In this respect, this Federal Circuit decision may signal a tough road ahead for aftermarket suppliers.

Takeaway

- Use design patents not only to protect a product as a whole, but also to protect the smallest sellable component of the product.

[1] Interestingly, a district court recently determined that trademark protection extended to the combination of “John Deere green” and “John Deere yellow” as a color scheme.

Predictability and Criticality – Disclosure of Species Can Support Broader Genus

| August 5, 2019

IN RE: GLOBAL IP HOLDINGS LLC

July 5, 2019

Before Moore, Reyna, and Stoll

Summary

This precedential decision illustrates that disclosure of a species can support a broader genus claim. The test for sufficiency is whether the specification “reasonably conveys to those skilled in the art that the inventor had possession of the claimed subject matter as of the filing date.” Predictability and criticality are relevant to the written description inquiry.

Background

Global IP Holdings LLC (Global) filed a reissue application seeking to broaden the claims of its U.S. Patent No. 8,690,233[1]. The reissue application sought to change the term “thermoplastic” to “plastic” in independent claims 1, 14 and 17. Claim 1 is representative:

1. A carpeted automotive vehicle load floor comprising:

a composite panel having first and second reinforced

thermoplastic skins and athermoplastic cellular core disposed between and bonded to the skins, the first skin having a top surface;a cover having top and bottom surfaces and spaced apart from the composite panel; and

a substantially continuous top covering layer bonded to the top surface of the panel and the top surface of the cover to at least partially form a carpeted load floor having a carpeted cover, wherein an intermediate portion of the top covering layer between the cover and the panel is not bonded to either the panel or the cover to form a living hinge which allows the carpeted cover to pivot between different use positions relative to the rest of the load floor.

The reissue declaration of the inventor explained that he is the inventor of over fifty U.S. patents in the field of plastic-molded products and that he was aware of the use of other plastics than thermoplastics (such as thermoset plastics) for composite panels with a cellular core.

The claims of the reissue application were rejected for failing to comply with the written description requirement of 35 U.S.C. § 112, first paragraph. The Examiner noted that the specification only describes the skins and core being formed of thermoplastic materials. Thus, the Examiner considered the change to result in new matter.

On appeal to the Patent Trademark and Appeal Board (PTAB), Global argued that “because the type of plastic used is not critical to the invention and plastics other than thermoplastics were predictable options, the disclosure of thermoplastics (species) supports the claiming of plastics (genus).” The PTAB rejected these arguments, explaining that “regardless of the predictability of results of substituting alternatives, or the actual criticality of thermoplastics in the overall invention, [Global’s] Specification, as a whole, indicates to one of ordinary skill in the art that the inventors had possession only of the skins and core comprising specifically thermoplastic.”

Discussion

The CAFC reviewed the PTAB’s legal conclusions de novo and its fact finding for substantial evidence. The CAFC found that the PTAB legally erred in its analysis. In particular, the PTAB’s finding that the specification was insufficient “regardless of the predictability of results of substituting alternatives, or actual criticality of thermoplastics in the overall invention” conflicts with Ariad Pharm., Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co., 598 F.3d 1336, 1351 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (en banc). The CAFC explained that “the predictability of substituting generic plastics for thermoplastics in the skins and cellular cores of vehicle load floors is relevant to the written description inquiry.” In addition, criticality of an unclaimed limitation to the invention “can be relevant to the written description requirement.”

The CAFC pointed to In re Peters, 723 F.2d 891, 893–94 (Fed. Cir. 1983), in which the original claims were directed to a metal tip having a tapered shape. In a reissue application of that patent, the claims were amended to cover both tapered and non-tapered tips. The Board held that the broadened claims were not supported because the original disclosure only disclosed tapered tips. The CAFC disagreed, explaining that:

“[t]he broadened claims merely omit an unnecessary limitation that had restricted one element of the invention to the exact and non-critical shape disclosed in the original patent.” Id. We reasoned that the disclosed tip configuration was not critical because no prior art was overcome based on the tip shape and “one skilled in the art would readily understand that in practicing the invention it is unimportant whether the tips are tapered.”

Accordingly, the decision of the PTAB is vacated and remanded to address the relevant factors including predictability and criticality in order to determine whether the written description requirement has been satisfied.

Takeaways

Although a specification may not literally disclose a broader genus, disclosure of a species may support a broader genus, depending on the predictability and criticality of the feature.

Could Global seek an even broader claim by deleting “thermoplastic” in its entirety? Perhaps so, if deletion of thermoplastic is considered not critical to overcome prior art as in In re Peters. A review of the patent does show use of generic terms of “skin” and “cellular core” (column 5, lines 1-26 for example).

[1] A review of the file history shows that 15 patents issued from the same priority application no. 13/453,201.

Plausible and specific factual allegations of inventive claims are enough to survive a motion to dismiss for Patent Ineligible Subject Matter

| July 22, 2019

Cellspin Soft, Inc. v. Fitbit, Inc.

June 25, 2019

Lourie, O’Malley, and Taranto

Summary:

Cellspin sued Fitbit and nine other defendants for infringement of various claims of four different patents relating to connecting a data capture device such as a digital camera to a mobile device. Fitbit filed a motion to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(6) because the asserted claims of all of the patents are to patent ineligible subject matter under § 101. The district court granted the motion to dismiss and Cellspin appealed to the CAFC. The CAFC agreed with the district court that the claims recite an abstract idea under step one of the Alice test. However, under step two of the Alice test, the CAFC stated that Cellspin made “specific, plausible factual allegations about why aspects of its claimed inventions were not conventional,” and that “the district court erred by not accepting those allegations as true.” Thus, the CAFC vacated the district court decision and remanded.

Details:

Cellspin sued Fitbit and nine other defendants for infringement of several claims of four different patents. The four patents are U.S. Patent Nos. 8,738,794; 8,892,752; 9,258,698; and 9,749,847. These patents share the same specification and relate to connecting a data capture device such as a digital camera, to a mobile device so that a user can automatically publish content from the data capture device to a website.

According to the ‘794 patent, prior art devices had to transfer their content from the digital capture device to a personal computer using a memory stick or cable. The ‘794 patent teaches using a short-range wireless communication protocol such as bluetooth to automatically or with minimal user intervention transfer and upload data from a data capture device to a mobile device. The mobile device can then automatically or with minimal user intervention publish the content on websites.

Claim 1 of the ‘794 patent recites:

1. A method for acquiring and transferring data from a Bluetooth enabled data capture device to one or more web services via a Bluetooth enabled mobile device, the method comprising:

providing a software module on the Bluetooth enabled data capture device;

providing a software module on the Bluetooth enabled mobile device;

establishing a paired connection between the Bluetooth enabled data capture device and the Bluetooth enabled mobile device;

acquiring new data in the Bluetooth enabled data capture device, wherein new data is data acquired after the paired connection is established;

detecting and signaling the new data for transfer to the Bluetooth enabled mobile device, wherein detecting and signaling the new data for transfer comprises:

determining the existence of new data for transfer, by the software module on the Bluetooth enabled data capture device; and

sending a data signal to the Bluetooth enabled mobile device, corresponding to existence of new data, by the software module on the Bluetooth enabled data capture device automatically, over the established paired Bluetooth connection, wherein the software module on the Bluetooth enabled mobile device listens for the data signal sent from the Bluetooth enabled data capture device, wherein if permitted by the software module on the Bluetooth enabled data capture device, the data signal sent to the Bluetooth enabled mobile device comprises a data signal and one or more portions of the new data;

transferring the new data from the Bluetooth enabled data capture device to the Bluetooth enabled mobile device automatically over the paired Bluetooth connection by the software module on the Bluetooth enabled data capture device;

receiving, at the Bluetooth enabled mobile device, the new data from the Bluetooth enabled data capture device;

applying, using the software module on the Bluetooth enabled mobile device, a user identifier to the new data for each destination web service, wherein each user identifier uniquely identifies a particular user of the web service;

transferring the new data received by the Bluetooth enabled mobile device along with a user identifier to the one or more web services, using the software module on the Bluetooth enabled mobile device;

receiving, at the one or more web services, the new data and user identifier from the Bluetooth enabled mobile device, wherein the one or more web services receive the transferred new data corresponding to a user identifier; and

making available, at the one or more web services, the new data received from the Bluetooth enabled mobile device for public or private consumption over the internet, wherein one or more portions of the new data correspond to a particular user identifier.

The opinion highlighted as relevant that claim 1 requires establishing a paired connection between the data capture device and the mobile device before data is transmitted between the two. The other claims from the other patents recite small variations of claim 1 of the ‘794 patent.

Nine defendants filed a motion to dismiss under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) and one defendant filed a motion to dismiss under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(c). The motions argued that the asserted patents are ineligible under § 101. The district court granted the motions to dismiss stating that all of the asserted claims from all of the asserted patents are to ineligible subject matter under § 101.

CAFC – Step One Analysis

Cellspin argued that the claims are directed to improving internet-capable data capture devices and mobile networks and that its claims recite technological improvements because the claims describe improving data capture devices by allowing even “internet-incapable” capture devices to transfer newly captured data to the internet via an internet capable mobile device.

The CAFC characterized the claims as “drawn to the idea of capturing and transmitting data from one device to another.” And the CAFC stated that they have “consistently held that similar claims reciting the collection, transfer, and publishing of data are directed to an abstract idea,” and that these cases “compel the conclusion that the asserted claims are directed to an abstract idea as well.” The CAFC further stated that the patents acknowledge that users could already transfer data from a data capture device (even an internet-incapable device) to a website using a cable connected to a PC, and that the patents provided a way to automate this transfer. Thus, the CAFC concluded that the district court correctly held that the asserted claims are to an abstract idea.

CAFC – Step Two Analysis

Cellspin argued that the claimed invention was unconventional. They described the prior art devices as including a capture device with built-in wireless internet, but that these devices were inferior because at the time of the patent priority date, these combined devices were bulky, expensive in terms of hardware and expensive in terms of requiring an extra or separate cellular service for the data capture device. Cellspin stated that its device was unconventional in that it separated the steps of capturing and publishing the data by separate devices linked by a wireless, paired connection. This invention allowed for the data capture device to serve one core function of capturing data without the need to incorporate other hardware and software components for storing data and publishing on the internet. And one mobile device with one data plan can be used to control several data capture devices.

Cellspin further argued that its specific ordered combination of elements was inventive because Cellspin’s claimed device requires establishing a paired connection between the mobile device and the data capture device before data is transmitted, whereas the prior art data capture device forwarded data to a mobile device as captured regardless of whether the mobile device is capable of receiving the data, i.e. whether the mobile device is on and whether the mobile device is near the data capture device. Cellspin also argued that its use of HTTP transfers of data received over a paired connection to web services was non-existent prior to its invention.

The district court stated that Cellspin failed to cite support in the patent specifications for its allegations regarding the inventive concepts and benefits of its invention. However, the CAFC stated that in the Aatrix case (Aatrix Software Inc. v. Green Shades Software, Inc., 882 F.3d 1121 (Fed. Cir. 2018)), they repeatedly cited allegations in the complaint to conclude that the disputed claims were potentially inventive. The CAFC stated:

While we do not read Aatrix to say that any allegation about inventiveness, wholly divorced from the claims or the specification, defeats a motion to dismiss, plausible and specific factual allegations that aspects of the claims are inventive are sufficient. Id. As long as what makes the claims inventive is recited by the claims, the specification need not expressly list all the reasons why this claimed structure is unconventional.

The CAFC stated that in this case, Cellspin made “specific, plausible factual allegations about why aspects of its claimed inventions were not conventional,” and that “the district court erred by not accepting those allegations as true.”

The district court also did not give weight to Cellspins’ allegations because Cellspin relied on Berkheimer (Berkheimer v. HP Inc., 881 F.3d 1360 (Fed. Cir. 2018)), which was distinguished by the district court because the Berkheimer case dealt with a motion for summary judgment. But the CAFC stated that the district court’s conclusion cannot be reconciled with the Aatrix case and stated:

The district court thus further erred by ignoring the principle, implicit in Berkheimer and explicit in Aatrix, that factual disputes about whether an aspect of the claims is inventive may preclude dismissal at the pleadings stage under § 101.

The CAFC further stated that Cellspin did more than just label certain techniques as inventive; Cellspin pointed to evidence suggesting that these techniques had not been implemented in the same way. The CAFC concluded that Cellspin sufficiently alleged that they claimed significantly more than the idea of capturing, transferring or publishing data, and thus the district court erred by granting the motion to dismiss.

Attorney Fees

The CAFC also commented on the district court’s decision to award attorney fees to the defendant. The district court awarded attorney fees to the defendants because the district court deemed the case exceptional due to actions by Cellspin. But since the CAFC found that the district court erred in granting the motions to dismiss, the CAFC vacated the award of attorney fees. But the CAFC went further to point out errors by the district court in determining the case to be exceptional.

The CAFC faulted the district court for not presuming that the issued patents are eligible. The CAFC stated that issued patents are not only presumed to be valid but also presumed to be patent eligible. In citing Berkheimer, the CAFC stated that underlying facts regarding whether a claim element or combination is well-understood or routine must be proven by clear and convincing evidence.

Comments

A patent owner as a plaintiff in an infringement suit can defend against a motion to dismiss by providing “specific, plausible factual allegations” about why aspects of the claimed invention were not conventional. Explicit description in the specification providing reasons why the claimed invention is unconventional is not required as long as the claim recites what makes the claim inventive. Also, this case states that underlying facts regarding ineligibility must be proven by clear and convincing evidence.

Even though this case states that explicit description in the specification regarding why the invention is unconventional is not required, patent applicants should consider including a description in the specification regarding why the invention or certain aspects of the invention are unconventional to make their patents stronger.

The Federal Circuit Affirms PTAB’s Obvious Determination Against German-Based Non-Practicing Entity, Papst Licensing GMBH & Co., Based on Both Issue Preclusion and Lack of Merit

| July 19, 2019

Papst Licensing GMBH & Co. v. Samsung

May 23, 2019

Dyk, Taranto, and Chen. Opinion by Taranto

Summary

German-based non-practicing entity Papst Licensing GMBH & Co. is the owner of U.S. Patent No. 9,189,437 entitled “Analog Data Generating and Processing Device Having a Multi-Use Automatic Processor.” The ‘437 patent issued in 2015 and claims priority to an original application filed in 1999 through continuation applications, and is one of a family of at least seven patents based on the same specification and/or priority that have been asserted in litigations by Papst against various entities to seek licenses. Here, Samsung successfully brought an Inter Parties Review (IPR) proceeding before the Patent & Trademark Appeal Board (PTAB) in which the PTAB held that claims of the ‘437 were invalid as obvious over prior art. Papst appealed the PTAB’s decision, and, on appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s decision based on both issue preclusion and obviousness.

Details

Procedural Background

German-based non-practicing entity Papst Licensing GMBH & Co. (“Papst”)

is the owner of U.S. Patent No. 9,189,437 entitled “Analog Data Generating and

Processing Device Having a Multi-Use Automatic Processor.” The ‘437 patent issued in 2015 and claims

priority to an original application filed in 1999 through continuation

applications, and is one of a family of at least seven patents based on the same

specification and/or priority that have been asserted in litigations by Papst

against various companies to seek licenses.

In response to such litigations, various combinations of companies filed

numerous petitions for Inter Partes Review (IPR) to review many claims of the

family of patents. In this case,

Samsung successfully initiated an IPR proceeding before the Patent &

Trademark Appeal Board (PTAB) in which the PTAB held that claims of the ‘437

were invalid as obvious over prior art.

Factual Background

The patent at issue on appeal is U.S. Patent No. 9,189,437 is entitled “Analog Data Generating and Processing Device Having a Multi-Use Automatic Processor.” The specification describes an interface device for communication between a data device (on one side of the interface) and a host computer (on the other). The interface device achieves high data transfer rates, without the need for a user-installed driver specific to the interface device, by using fast drivers that are already standard on the host computer for data transfer, such as a hard-drive driver. In short, the interface device sends signals to the host device that the interface device is an input/output device for which the host already has such a driver – i.e., such that the host device perceives the interface device to actually be that other input/output device.

For reference, claim 1of the ‘437 patent is shown below:

1. An analog data generating and processing de-vice (ADGPD), comprising:

an input/output (i/o) port;

a program memory;

a data storage memory;

a processor operatively interfaced with the i/o port, the program memory and the data storage memory;

wherein the processor is adapted to implement a data generation process by which analog data is acquired from each respective analog acquisition channel of a plurality of independent analog acquisition channels, the analog data from each respective channel is digitized, coupled into the processor, and is processed by the processor, and the processed and digitized analog data is stored in the data storage memory as at least one file of digitized analog data;

wherein the processor also is adapted to be involved in an automatic recognition process of a host computer in which, when the i/o port is operatively interfaced with a multi-purpose interface of the host computer, the processor executes at least one instruction set stored in the program memory and thereby causes at least one parameter identifying the analog data generating and processing device, independent of analog data source, as a digital storage device instead of an analog data generating and processing device to be automatically sent through the i/o port and to the multi-purpose interface of the computer (a) without requiring any end user to load any software onto the computer at any time and (b) without requiring any end user to interact with the computer to set up a file system in the ADGPD at any time, wherein the at least one parameter is consistent with the ADGPD being responsive to commands is-sued from a customary device driver;

wherein the at least one parameter provides information to the computer about file transfer characteristics of the ADGPD; and

wherein the processor is further adapted to be involved in an automatic file transfer process in which, when the i/o port is operatively interfaced with the multi-purpose interface of the computer, and after the at least one parameter has been sent from the i/o port to the multi-purpose interface of the computer, the processor executes at least one other instruction set stored in the program memory to thereby cause the at least one file of digitized analog data acquired from at least one of the plurality of analog acquisition channels to be transferred to the computer using the customary device driver for the digital storage device while causing the analog data generating and processing device to appear to the computer as if it were the digital storage device without requiring any user-loaded file transfer enabling software to be loaded on or in-stalled in the computer at any time.

a. The Board’s IPR Decision Related to the ‘437 Patent

Before the PTAB, the board held that the relevant claims of the ‘437 – claims 1-38 and 43-45 – were invalid as obvious over U.S. Patent No. 5,758,081 (Aytac), a publication setting forth standards for SCSI interfaces (discussed in the ‘081 patent) and “admitted” prior art described in the ‘437 patent.

The Aytac patent describes connecting a personal computer to an interface device that would in turn connect to (and switch between) various other devices, such as a scanner, fax machine, or telephone. The interface device includes the “CaTbox,” which is connected to a PC via SCSI cable, and to a telecommunications switch.

In its determination of obviousness, the Board adopted a claim construction that is central to Papst’s appeal. In particular, claim 1 of the ‘437 patent requires an automatic recognition process to occur “without requiring any end user to load any software onto the computer at any time” and an automatic file transfer process to occur “without requiring any user-loaded file transfer enabling software to be loaded on or installed in the computer at any time.”

The Board interpreted the “without requiring” limitations to mean “without requiring the end user to install or load specific drivers or software for the ADGPD beyond that included in the operating system, BIOS, or drivers for a multi-purpose interface or SCSI interface.” In adopting that construction, among those that can be required to be installed for the processes to occur, relying on the specification and claims as making clear that the invention contemplates use of SCSI drivers to carry out the processes.

The Board also rejected Papst’s contention that “the ‘without requiring’ limitations prohibit an end user from installing or loading other drivers.”

b. The Board’s IPR Decision Related to the ‘144 Patent

With respect to another U.S. Patent in Papst’s family of patents – i.e., U.S. Patent No. 8,966,144, which is based on the same specification as the ‘437 patent – the PTAB had issued a similar IPR decision, in which the same claim limitations of “without requiring …” were similarly interpreted as in the present board decision and in which the claim limitation was similarly found to be obvious over the same prior art as applied in the present board decision.

Following the PTAB decision related

to the ‘144 patent, Papst appealed the decision to the Federal Circuit. However, on the eve before oral arguments,

Papst voluntarily dismissed its appeal, whereby the PTAB’s decision related to

the ‘144 patent became final.

Discussion

On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s decision based on both issue preclusion and obviousness.

- Issue Preclusion

The Federal Circuit explained that “[t]he Supreme Court has made clear that, under specified conditions, a tribunal’s resolution of an issue that is only one part of an ultimate legal claim can preclude the loser on that issue from later contesting, or continuing to contest, the same issue in a separate case. Thus:

subject to certain well-known exceptions, the general rule is that “[w]hen an issue of fact or law is actually litigated and determined by a valid and final judgment, and the determination is essential to the judgment, the determination is conclusive in a subsequent action between the parties, whether on the same or a different claim.”

The Federal Circuit noted that “we have held that the same is true of an IPR proceeding before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, so that the issue preclusion doctrine can apply in this court to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s decision in an IPR once it becomes final.”

The well-known exception, noted by the Federal Circuit, involved that: the court recognizes that “[i]ssue preclusion may be in-apt if ‘the amount in controversy in the first action [was] so small in relation to the amount in controversy in the second that preclusion would be plainly unfair.”

However, the Federal Circuit emphasized that that was not the case here, and, the court also emphasized that, in the ‘144 case Papst even brought the litigation through to the eve of oral argument, which highlights that that was not the case. Notably, the Federal Circuit also emphasizes that: “More generally, given the heavy burdens that Papst placed on its adversaries, the Board, and this court by waiting so long to abandon defense of the ’144 patent and ’746 patent claims, Papst’s course of action leaves it without a meaningful basis to argue for systemic efficiencies as a possible reason for an exception to issue preclusion.”

With respect to issue preclusion, the Federal Circuit explained that the Board in the ’144 patent decisionresolved the same claim construction issue in the same way as the Board in the present IPR. It characterized “the issue in dispute” as “center[ing] on whether the ‘without requiring’ limitations prohibit an end user from installing or loading other drivers.” Moreover, the Federal Circuit also explained that “the Board also ruled that use of SCSI software does not violate the ‘without requiring’ limitations, because the patent clearly showed that such software may be used,” and that “[t]hat ruling was not just materially identical to the Board’s claim construction ruling in this case; it also was essential to the Board’s ultimate determination, which depended on finding that the installation of CATSYNC, as disclosed in Aytac, was not prohibited by the ’144 patent’s “without requiring” limitation and that Aytac taught that the transfer process could be performed with SCSI software.”

Thus, the Federal Circuit held that issue preclusion applied in this case related to the ‘437 patent.

- Obviousness

On appeal, Papst presents two arguments that are addressed by the Federal Circuit First, Papst argues that the board improperly construed the limitation “without requiring” as meaning that the claimed processes can take place with SCSI software (or other multi-purpose interface soft-ware or software included in the operating system or BIOS).. Second, Papst argues that the board improperly concluded that Aytac teaches an automatic file transfer that can take place with only the SCSI drivers, without the assistance of user-added CATSYNC software.

With respect to the obviousness evaluation, the Federal Circuit found the Board’s conclusion regarding the construction of the “without requiring” limitations of the ‘437 patent to be correct based on the “ordinary meaning” of the words employed. The Federal Circuit explained that “[t]o state that a process can take place “without requiring” a particular action or component is, by the words’ ordinary meaning as confirmed in Celsis In Vitro, to state simply that the process can occur even though the action or component is not present; it is not to forbid the presence of the particular action or component.”

In addition, the Federal Circuit also agreed with the Board’s conclusion that SCSI interface software was permitted software in the claim construction because of the description in the specification of the ‘437 patent. The Federal Circuit expressed that: “The specification is decisive. Reflecting the recognition that SCSI interfaces were ‘present on most host devices or laptops’ at the time” and that “the specification explains that the invention contemplates use of SCSI software.”

Moreover, the Federal Circuit agreed that the “Board’s finding that a relevant skilled artisan would understand that the Aytac’s CaTbox can perform an automatic file transfer using SCSI without the CATSYNC software that Papst says is required, ” noting that Samsung’s expert Dr. Reynolds testified that only the SCSI protocol and the ASPI drivers are needed to transfer a file in Aytac, similar to the function of the ’437 patent.

Thus, the Federal Circuit affirmed the board’s determinations of obviousness related to the ‘437 patent.

Takeaway

When asserting patent infringement of multiple similar patents in a patent family, there is an increased risk of facing issue preclusion issues.

There is a Standing to Defend Your Expired Patent Even If an Infringement Suit Has Been Settled

| July 8, 2019

Sony Corp. v. Iancu

Summary:

The CAFC vacated the PTAB’s decision, in which the PTAB found that the limitation “reproducing means” is not computer-implemented and does not require an algorithm because this limitation should have been construed as computer-implemented and that the corresponding structure is a synthesizer and controller that performs the algorithm described in the specification. In addition, the CAFC found that there is a standing to appeal to defend an expired patent because the CAFC’s decision would have a consequence on any infringement that took place during the life of the patent.

Details:

Sony is the owner of U.S. Patent No. 6,097,676 (“the ’676 patent”) and appeals the PTAB’s decision in IPR, in which the PTAB found claims 5 and 8 of the ’676 patent unpatentable as obvious.

The ’676 patent:

The ’676 patent is directed to an information recording medium that can store audio data having multiple channels and a reproducing device that can select which channel to play based on a default code or value stored in a memory. This reproducing device has (1) storing means for storing the audio information, (2) reading means for reading codes associated with the audio information, and (3) reproducing means for reproducing the audio information based on the default code or value.

Claim 5 of the ’676 patent recites:

5. An information reproducing device for reproducing an information recording medium in which audio data of plural channels are multiplexedly recorded, the information reproducing device comprising:

storing means for storing a default value for designating one of the plural channels to be reproduced; and

reproducing means for reproducing the audio data of the channel designated by the default value stored in the storing means; and

wherein a plurality of voice data, each voice data having similar contents translated into different languages are multiplexedly recorded as audio data of plural channels; and a default value for designating the voice data corresponding to one of the different languages is stored in the storing means.

Claim 8 recites the same features as claim 5 with some additional features.

The PTAB:

The PTAB instituted IPR as to claims 5 and 8 of the ’676 patent. The issue during IPR was whether the “reproducing means” was computer-implemented and required an algorithm.

On September, 2017, the PTAB issued a final decision, where the claims were found to be unpatentable as obvious over the Yoshio reference. The PTAB construed the “reproducing means” has a means-plus-function limitation, and found that its corresponding structure is a controller and a synthesizer, or the equivalents. Furthermore, the PTAB found that this limitation is not computer-implemented and does not require an algorithm because a controller and a synthesizer are hardware elements.

The CAFC:

The CAFC agreed with Sony’s argument that the “reproducing means” requires an algorithm to carry out the claimed function.

The CAFC held that:

“In cases involving a computer-implemented invention in which the inventor has invoked means-plus-function claiming, this court has consistently required that the structure disclosed in the specification be more than simply a general purpose computer or microprocessor.” Aristocrat Techs. Austl. Pty Ltd. v. Int’l Game Tech., 521 F.3d 1328, 1333 (Fed. Cir. 2008). For means-plus-function claims “in which the disclosed structure is a computer, or microprocessor, programmed to carry out an algorithm,” we have held that “the disclosed structure is not the general purpose computer, but rather the special purpose computer programmed to perform the disclosed algorithm.” WMS Gaming, Inc. v. Int’l Game Tech., 184 F.3d 1339, 1349 (Fed. Cir. 1999).

The specification of the ’676 patent discloses that “[i]n reproducing such a recording medium by using the reproducing device of the present invention, the processing as shown in FIG. 16 is executed.” In fact, Fig. 16 discloses an algorithm in the form of a flowchart.

Therefore, the CAFC held that the “reproducing means” of claims 5 and 8 of the ’676 patent should be construed as computer-implemented and that the corresponding structure is a synthesizer and controller that performs the algorithm described in the specification.

Accordingly, the CAFC vacated the PTAB’s decision and remand for further consideration of whether the Yoshio reference discloses a synthesizer and controller that performs the algorithm described in the specification, or equivalent, and whether the claims would have been obvious over the Yoshio reference.

Standing to Appeal:

The ’676 patent was expired in August 2017. Petitioners have elected not to participate in the appeal before the CAFC. The parties have settled the district court infringement suit involving this patent.

Is there a standing to appeal?

Majority: YES because

- The parties to this appeal remain adverse and none has suggested the lack of an Article III case or controversy.

- The PTO argues that the PTAB’s decision should be affirmed.

- Sony argues that the PTAB’s decision should be reversed and the claims should be patentable.

- The CAFC’s decision would have a consequence on any infringement that took place during the life of the ’676 patent (past damages subject to the 6-year limitation and the owner of an expired patent can license the rights or transfer title to an expired patent).

Dissenting: NO because

- No private and public interest (patent expired, petitioner declined to defend its victory, and infringement suit has been settled).

- No hint or possibility of present or future case or controversy by both parties and the PTO.

Takeaway:

- Even if the patent has expired, the patentee has a standing to appeal before the CAFC to dispute the PTAB’s final decision.

- An algorithm described in the specification for means-plus-function language helped the patentee with a narrow claim construction.

Tags: 112(f) > case or controversy > expired patent > hardware > infringement > means-plus-function > software > standing to appeal

Satisfying Written Description When Therapeutic Effectiveness is Claimed

| June 26, 2019

Nuvo Pharmaceuticals v. Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories

Summary

The CAFC reversed and dismissed a holding by the District Court that the claims of the ‘907 and the ‘285 patents had adequate written description regarding the efficacy of an uncoated PPI. The CAFC states that it not necessary to prove that a claimed pharmaceutical compound actually achieves a certain result. However, if the claim recites said result, then there must be sufficient support in the specification. Herein, the claims were held invalid because the therapeutic effectiveness of uncoated PPI, which was recited in the claims, was not supported by the specification.

Details

The use of a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (hereinafter “NSAID”), such as aspirin, can cause gastrointestinal problems, and thus, some patients are prescribed an acid inhibitor, such as proton pump inhibitor (PPI), to be taken with said NSAID. However, even this combination therapy may be problematic. That is, if the PPI has not taken affect before the administration of the NSAID then gastrointestinal problems may still occur.

The U.S. Patent Nos. 6,926,907 (hereinafter “the ‘907 patent”) and 8,557,285 (hereinafter “the ’285 patent”) are directed towards a coordinated release drug formulation comprising an acid inhibitor/PPI and a NSAID. The coordinated release drug allows for an acid inhibitor to work before the release of the NSAID and thereby minimizes potential gastrointestinal problems. The ‘285 patent is a related patent of the ‘907 patent and both share a specification. Claim 1 of the ‘907 patent and claim 1 of the ‘285 patent are presented below:

Claim 1 of the ’907 patent:

1. A pharmaceutical composition in unit dosage form suitable for oral administration to a patient, comprising:

(a) an acid inhibitor present in an amount effective to raise the gastric pH of said patient to at least 3.5 upon the administration of one or more of said unit dosage forms;

(b) a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) in an amount effective to reduce or eliminate pain or inflammation in said patient upon administration of one or more of said unit dosage forms;

and wherein said unit dosage form provides for coordinated release such that:

i) said NSAID is surrounded by a coating that, upon ingestion of said unit dosage form by said patient, prevents the release of essentially any NSAID from said dosage form unless the pH of the surrounding medium is 3.5 or higher;

ii) at least a portion of said acid inhibitor is not surrounded by an enteric coating and, upon ingestion of said unit dosage form by said patient, is released regardless of whether the pH of the surrounding medium is below 3.5 or above 3.5.

(emphasis added)

Claim 1 of the ’285 patent:

1. A pharmaceutical composition in unit dosage form comprising therapeutically effective amounts of:

(a) esomeprazole, wherein at least a portion of said esomeprazole is not surrounded by an enteric coating; and

(b) naproxen surrounded by a coating that inhibits its release from said unit dosage form unless said dosage form is in a medium with a pH of 3.5 or higher;

wherein said unit dosage form provides for release of said esomeprazole such that upon introduction of said unit dosage form into a medium, at least a portion of said esomeprazole is released regardless of the pH of the medium.

(emphasis added)

Nuvo, who owns the ‘907 and ‘285 patents, make and sells Vimovo, which is the commercial embodiment of the patents. The patented drug achieves a coordinated release of the acid inhibitor and the NSAID in a single tablet. The core of the tablet is NSAID, which is coated so as to prevent its release before the pH has increased to a desired level, and an acid inhibitor, like PPI, on the outside of the coating, that actively works to increase the pH to said desired level. The PPI is uncoated. The specifications discloses methods for preparing and making the claimed drug formulations and provides examples of the structure and ingredients of the drug formulations but does not disclose any experimental data demonstrating the therapeutic effectiveness of any amount of uncoated PPI and coated NSAID in a single dosage form. Id. at 6. The specification discloses that coated PPIs avoid destruction by stomach acid but may not work quickly enough and the specification does not have any disclosure regarding the effectiveness of uncoated PPIs being able to raise pH. The inventor of the ‘907 and ‘285 patents recognized that an uncoated PPI is at greater risk of being destroyed by stomach acid, which would undermine the effectiveness of the PPI, but contemplated that uncoated PPI would allow for immediate release into a patient’s stomach and achieve an increase in pH level.

Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Inc., Mylan Pharmaceuticals, and Lupin Pharmaceuticals (hereinafter “the Generics”) submitted an Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration seeking approval to sell a generic version of Vimovo. Dr. Reddy’s submitted a second ANDA wherein the product would contain a small amount of uncoated NSAID on the outermost layer of the tablet, which is separate from the coated-core-NSAID.

Nuvo sued the Generics in the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey, in order to prevent the Generics from entering the market upon approval of the ANDAs, alleging all ANDAs products would infringe the ‘907 and ‘285 patents. The Generics stipulated to infringement, except for Dr. Reddy’s second ANDA product, and then countered that the ‘907 and ‘285 patents were invalid for obviousness, lack of enablement and inadequate written description.

The District Court granted Dr. Reddy’s motion for summary judgment of noninfringment of the ‘907 patent with regards to the second ANDA product. A bench trail was held regarding the validity of the ‘907 patent, the ‘285 patent, and whether the second ANDA product by Dr. Reddy infringed the ‘285 patent. It was concluded that the claims were not obvious over the prior art “because it was nonobvious to use a PPI to prevent NSAID-related gastric injury, and persons of ordinary skill in the art were discouraged by the prior art from using uncoated PPI and would not have reasonably expected it to work.” Id. at 8. It was also held that the claims of both patents were enabled and there was sufficient written description. The District Court held that the second ANDA by Dr. Reddy infringes the claims of the ‘285 patent.

At the District Court, the Generics argued that, “if they lose on their obviousness contention, then the claims lack written description support for the claimed effectiveness of uncoated PPI because ordinarily skilled artisans would not have expected it to work and the specification provides no experimental data or analytical reasoning showing the inventor possessed an effective uncoated PPI.” Id. at 9. Nuvo countered that “experimental data and an explanation of why an invention works are not required, the specification adequately describes using uncoated PPI, and its effectiveness is necessarily inherent in the described formulation.” Id. at 9. The District Court rejected Nuvo’s argument that effectiveness does not need to be described because effectiveness is inherent. The District Court acknowledged that the specification of the ‘907 and ‘285 patents did not describe efficacy of uncoated PPI. However, the District Court did conclude that there was sufficient written description because “the specification described the immediate release of uncoated PPI and the potential disadvantages of coated PPI, namely that enteric-coated PPI sometimes works too slowly to raise the intragastric pH. The district court did not explain why the mere disclosure of immediate release uncoated PPI, coupled with the known disadvantages of coated PPI, is relevant to the therapeutic effectiveness of uncoated PPI, which the patent itself recognized as problematic for efficacy due to its potential for destruction by stomach acid.” Id. at 10. The Generics appeal the written description ruling and Nuvo cross-appeals the District Court grant of summary judgment of noninfringement. Based solely on the written description issue regarding the claim language of “efficacy”, the CAFC reversed the appeal and dismissed the cross-appeal.

Before the CAFC, the Generics argued that the patents claim uncoated PPI that raises the gastric pH to at least 3.5, but that in view of the District Court’s holding, as part of the obviousness analysis, a skilled artisan would not have expected uncoated PPI to be effective to raise gastric pH, and that the specification of the patents fails to disclose the effectiveness of uncoated PPI. Id. at 12. Nuvo argued that “the claims do not require any particular degree of efficacy of the uncoated PPI itself, it is enough that the specification discloses making and using drug formulations containing effective amounts of PPI and NSAID, and experimental data and additional explanations demonstrating the invention works are unnecessary.” Id. at 12. The CAFC held that the District Court’s analysis does not support its conclusion of adequate written description and gave a review of the record to establish that the clear error standard has been met. “A written description finding is review for a clear error.” Id. at 11.