Depends On How You Slice It: CAFC reverses PTAB on Weber v. Provisur IPR ruling

| April 5, 2024

Weber, Inc. v. Provisur Tech. Inc.

Decided: February 8, 2024

Before Reyna, Hughes and Stark. Authored by Reyna

Summary: The Court reversed the PTAB’s finding that Weber’s instruction manuals did not qualify as printed publications under 35 USC §102. The Court also reversed key claim construction taken by the PTAB in upholding Provisur’s patents.

Background:

Provisur sued Weber for patent infringement on two patents, USP 10,639,812 (“’812 patent”) and 10,625,436 (“’436 patent”) relate to high-speed mechanical slicers used in food-processing plants. Weber countered by filing IPR proceedings against both patents at the USPTO Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). The PTAB found both the ‘812 and the ‘436 patentable. During the PTAB proceeding, Weber had attempted to use their own instruction manual for the slicer they sold as a prior art publication under 35 U.S.C. §102. The Board found that the instruction manual was not a “printed publication” under §102 on the basis that the manuals were controlled in their circulation to only customers or potential customers by a strict copyright and confidentiality clause.

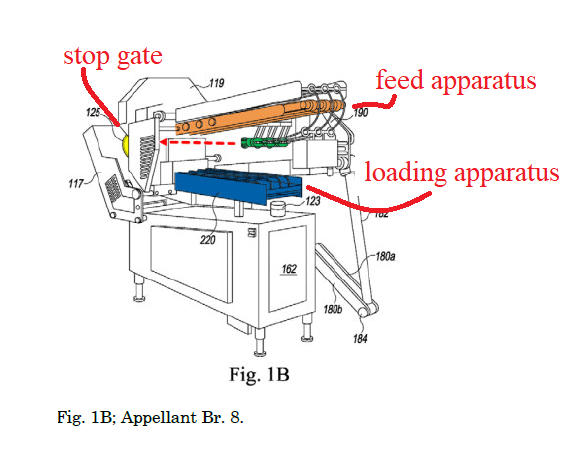

Further, the PTAB had construed three terms from the slicer components, (1) the “food article loading apparatus”; (2) the “food article feed apparatus”; and (3) the “food article stop gate” in a manner that maintained the patents’ validity while excluding the disclosures in Weber’s manuals.

Weber appealed the Board’s finding that their instruction manual was not a printed publication under §102 and the claim construction of the three terms.

Decision:

(a) Weber’s Instruction Manual as a “Printed Publication”

The Board had relied upon the CAFC’s prior holding in Cordis Corp. v. Boston Scientific Corp., 561 F.3d 1319 (Fed. Cir. 2009), in finding that Weber’s manuals were not “printed publications.” In Cordis, the references in question were two academic monographs describing an inventor’s work that were only distributed to a handful colleagues and two companies potentially interested in the technology.

The CAFC was quick to distinguish the current case from Cordis. First, the CAFC noted that the statutory phrase “printed publication” from § 102 has been defined to mean a reference that was “sufficiently accessible to the public interested in the art,” citing In re Klopfenstein, 380 F.3d 1345, 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2004) and that “public accessibility” was based on the relevant public being able to “locate the reference by reasonable diligence,” citing Valve Corp. v. Ironburg Inventions Ltd., 8 F.4th 1364, 1376 (Fed. Cir. 2021). Next, the Court found that Weber’s operating manuals were created for dissemination to the interested public to provide instructions for Weber’s slicer. The Court stated the Weber manuals were in “stark contrast” to the confidential monographs in Cordis which were subject to “academic confidentiality norms.” The Court went on to describe that the evidence provided by employees of Weber, stating that the manuals were readily provided to potential buyers, clearly indicated that the manuals did in fact qualify as “printed publications” under §102.

The Court also found the Board’s reliance on the copyright and confidentiality of Weber’s manuals to be misplaced. The Board had keyed in on the copyright language restricting the reproduction or transfer of the manuals and Weber’s “terms and conditions” stating that documents related to a sale of a slicer “remain the property of” Weber. The CAFC was not convinced that these statements made the manuals confidential to the point of not being a “printed publication”, stating:

Weber’s assertion of copyright ownership does not negate its own ability to make the reference publicly accessible. Cf. Correge v. Murphy, 705 F.2d 1326, 1328–30 (Fed. Cir. 1983) (“A mere assertion of ownership cannot convert what was in fact a public disclosure and offer to sell to numerous potential customers into a non-disclosure.”). The intellectual property rights clause from Weber’s terms and conditions covering sales, likewise, has no dispositive bearing on Weber’s public dissemination of operating manuals to owners after a sale has been consummated.

The Court reversed the PTAB’s finding that Weber’s instruction manuals were not “printed publications” within the meaning of 35 U.S.C. §102.

(b) Claim Construction – “disposed over” and “stop gate”

The Court next addressed the PTAB’s claim construction as to the term “disposed over” as used in the claims. The Board had construed the term “disposed over” to require that the “feed apparatus and its conveyor belts and grippers are ‘positioned above and in vertical and lateral alignment with’ the food article loading apparatus and its lift tray assembly.” The Court rejected this interpretation asserting that it reads elements into the claim which are not present. The Court noted that the specification and prosecution history did not impart any limited meaning to the term “disposed over” and therefore there was no basis for including the additional aspect that the feed apparatus and loading apparatus were in alignment. Citing Cyntec Co. v. Chilisin Elecs. Corp., 84 F.4th 979, 986 (Fed. Cir. 2023), the Court held that “Had the patent drafter intended to limit the claims” to address the alignment of the conveyor belts and lift tray assembly between the apparatuses, “narrower language could have been used in the claim.”

Running Provisur through the figurative slicer, the Court noted that Provisur did not dispute that Weber’s manuals satisfy the limitation under Weber’s proposed construction (i.e. that alignment is not required between the feed and loading apparatus). Hence, they concluded that their review of the Board’s claim construction is dispositive of the issue and that the Weber manuals do disclose the “disposed over” limitation.

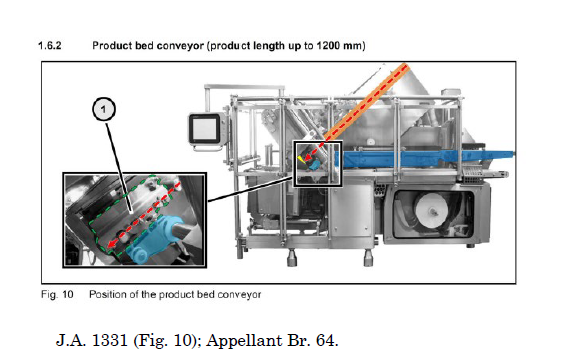

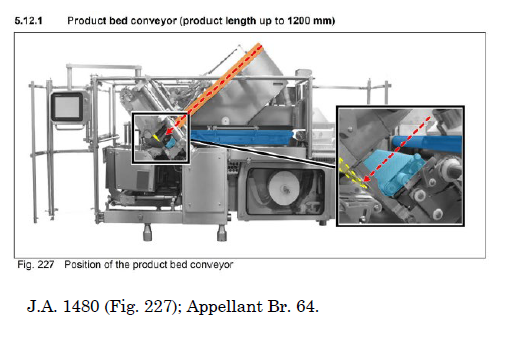

As to the “stop gate” term in the claims, Weber asserted that the Board erred in determining that the “product bed conveyer” disclosed in Weber’s operating manuals (as shown in Figures 10 and 227 thereof), does not disclose the “stop gate” limitation.

After analyzing the figures, the Court only commented that given these disclosures of the Weber manuals there was no substantial evidentiary support for the Board’s finding. Thus, the Court again reversed on the “stop gate” determinations.

Take aways:

- The Court clarifies the meaning of “printed publication” in 35 U.S.C. §102 by further defining the line between documents primarily intended to be confidential, such as the monographs in Cordis, and those primarily intended to be disseminated to the interested public, such as Weber’s manuals.

- By reversing the PTAB’s claim interpretation that had read a required alignment of parts into the claim where no such requirement was present, the Court also reiterates the standing law of claim construction that claim terms have their ordinary meaning unless intrinsic evidence demonstrates otherwise.

The Twists and Turns of Claim Construction Issues in an IPR

| February 2, 2024

Parkervision v. Vidal

Decided: December 20, 2023

Summary:

Although patent owner ParkerVision’s claim construction was adopted in multiple district court litigations, it was not adopted by the PTAB in the IPR of the same patent. The Federal Circuit, reviewing claim construction de novo, affirmed the Board’s final decision. ParkerVision introduced the claim construction issue in its patent owner response, arguing that the claimed “storage element” should be construed as “an element of an energy transfer system that stores non-negligible amounts of energy from an input EM signal” and that the cited prior art did not teach the claimed “storage element” because its allegedly corresponding capacitors were not part of any energy transfer system. Intel filed a reply asserting that the interpretation of a “storage element” does not require it to be part of an energy transfer system. The Board and the Federal Circuit agreed. ParkerVision did not further argue in its patent owner response that the cited prior art’s capacitors failed the requirement that it store “non-negligible” amounts of energy from the input EM signal. ParkerVision included in its sur-reply that the cited prior art’s capacitors stored only a negligible amount of energy because “non-negligible” must be measured relative to the available energy of the input EM signal. The Board granted Intel’s motion to strike this part of ParkerVision’s sur-reply. The court affirmed, noting that there was no abuse of discretion when the Board refused to consider a new theory of patentability raised for the first time in a sur-reply.

Procedural History:

Intel petitioned for inter partes review (IPR) of claim 3 of Parkervision’s USP 7,110,444 (the ‘444 patent). There are related district court litigations involving the ‘444 patent and other related patents, which adopted a claim construction of a “storage element” aligned with Parkervision’s proposed claim construction. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (the Board) adopted Intel’s claim construction of a “storage element” and issued a final decision that the ‘444 patent was obvious over cited prior art. Parkervision appealed. In issuing its final decision, the Board recognized that several district court cases involving the ‘444 patent adopted claim constructions inconsistent with Intel’s proposed construction. See, ParkerVision, Inc. v. Intel Corp., Nos. 6:20-cv-108-ADA, 6:20-cv-562-ADA (W.D. Tex.); ParkerVision, Inc. v. Hisense Co., Nos. 6:20-cv-870-ADA, 6:21-cv-562-ADA (W.D. Tex.); ParkerVision, Inc. v. TCL Indus. Holdings Co., No. 6:20-cv-945-ADA (W.D. Tex.); ParkerVision, Inc. v. LG Elecs. Inc., No. 6:21-cv-520-ADA (W.D. Tex.).

Decision:

Claim 3 of the ‘444 patent is as follows:

A wireless modem apparatus, comprising:

a receiver for frequency down-converting an input signal including,

a first frequency down-conversion module to down-convert the input signal, wherein said first frequency down-conversion module down-converts said input signal according to a first control signal and outputs a first down-converted signal;

a second frequency down-conversion module to down-convert said input signal, wherein said second frequency down-conversion module down-converts said input signal according to a second control signal and outputs a second down-converted signal; and

a subtractor module that subtracts said second down-converted signal from said first down-con-verted signal and outputs a down-converted signal;

wherein said first and said second frequency down-conversion modules each comprise a switch and a storage element.

The ‘444 patent relates to wireless local area networks (WLANs) that use frequency translation technology. In a two-device network using frequency translation, the first device receives a low-frequency baseband signal (audible voice signal) and up-converts it to a high-frequency electromagnetic (EM) signal before wireless transmission to the second device. The second device receives the EM signal, down-converts it back to a low-frequency baseband signal, and outputs an audible signal. The ‘444 patent is directed to down-converting EM signals using down-converter modules that include a switch and a storage element (also called a storage module).

The main issue in this case is the claim construction for a “storage element.”

ParkerVision contends that a “storage element” is an element of an energy transfer system that stores non-negligible amounts of energy from an input EM signal. A magistrate judge’s claim construction order in ParkerVision v. LG and a special master’s recommendation in ParkerVision v. Hisense and in ParkerVision v. TCL adopted ParkerVision’s proposed claim construction.

Intel contends that a “storage element” is “an element of a system that stores non-negligible amounts of energy from an input EM signal” – which does not require that the element be part of an energy transfer system. The Board adopted Intel’s claim construction. The Federal Circuit agreed. This is dispositive in the obviousness holding because ParkerVision’s patent owner response in the IPR focused exclusively on the prior art’s lack of an energy transfer system.

The ‘444 patent incorporated by reference USP 6,061,551 (the ‘551 patent) which provided the following disclosure critical to the meaning of a “storage element”:

1 FIG. 82A illustrates an exemplary energy transfer system 8202 for down-converting an input EM signal 8204. 2 The energy transfer system 8202 includes a switching module 8206 and a storage module illustrated as a storage capacitance 8208. 3 The terms storage module and storage capacitance, as used herein, are distinguishable from the terms holding module and holding capacitance, respectively. 4 Holding modules and holding capacitances, as used above, identify systems that store negligible amounts of energy from an under-sampled input EM signal with the intent of “holding” a voltage value. 5 Storage modules and storage capacitances, on the other hand, refer to systems that store non-negligible amounts of energy from an input EM signal.

(bracketed numbers identifying referenced sentences)

This is deemed “lexicographic” because “as used herein” in sentence #3 refers to the use of these terms (contained throughout the drawings and specification) in general, and not to specific embodiments, and “refer to” in sentence #5 links “storage modules” (parties agreed this is synonymous with “storage element”) to “systems that store non-negligible amounts of energy from an input EM signal.”

ParkerVision’s argued that the ‘551 paragraph was addressing examples in which storage modules are used in energy transfer systems in which holding modules, by contrast, are used in under-sampling systems. The court dismissed this because the comparative nature of the paragraph does not prevent it from being definitional. And, the court refused to incorporate an entire “energy transfer system” into the claim just because a single component (storage element) can be a part of such a system. The court also stated that the district court claim constructions by the magistrate judge and special masters do not alter its conclusion that the Board arrived at the correct construction.

Another, procedural, issue on appeal is whether (1) the Board erred in relying on Intel’s reply (raising this claim construction issue that “storage element” is not limited to being part of an “energy transfer system”) and (2) the Board erred in striking parts of ParkerVision’s sur-reply.

First, ParkerVision asserted that the Board erred in relying on Intel’s arguments allegedly raised for the first time in Intel’s reply. The presumed contention is that the Board deprived ParkerVision of its procedural rights under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) and failed to comply with the USPTO’s rule that a reply “may only respond to arguments raised in the … patent owner response…” 37 C.F.R. § 42.23(b). The court reviews the Board’s compliance with the APA de novo, and the Board’s determination that a party violated USPTO rules for abuse of discretion. Under the APA, the Board must:

“timely inform[]” the patent owner of “the matters of fact and law asserted,” 5 U.S.C. § 554(b)(3), must provide “all interested parties opportunity for the submission and consideration of facts [and] arguments . . . [and] hearing and decision on notice,” id. § 554(c), and must allow “a party . . . to submit rebuttal evidence . . . as may be required for a full and true disclosure of the facts,” id. § 556(d).

Dell Inc. v. Acceleron, LLC, 818 F.3d 1293, 1301 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

Neither petitioner nor patent owner expressly proposed any pre-institution claim construction. Post-institution, ParkerVision first proposed a new claim construction position in its patent owner response wherein “storage element” was construed as “an element of an energy transfer system that stores non-negligible amounts of energy from an input electromagnetic signal.” The APA required the Board to give Intel “adequate notice and an opportunity to respond under the new construction” proffered in ParkerVision’s patent owner response. As in Axonics, Inc. v. Medtronic, Inc., 75 F.4th 1374 (Fed. Cir. 2023), the court held that “where a patent owner in an IPR first proposes a claim construction in a patent owner response, a petitioner must be given the opportunity in its reply to argue and present evidence of anticipation or obviousness under the new construction….” Id. at 1384. Intel did just that. Intel’s reply countered that ParkerVision’s non-obviousness position that the cited prior art did not disclose the claimed “storage element” because it was not in an energy transfer system is misplaced because that term is not restricted to be an element of an energy transfer system.

Pursuant to the APA, the Board may not change theories mid-stream without giving the parties reasonable notice of its change. The Board’s adopting of Intel’s claim construction did not “change theories midstream without giving the parties reasonable notice of its change.” “Once ParkerVision introduced a claim construction argument into the proceeding through its patent owner response, Intel was entitled in its reply to respond to that argument and explain why that construction should not be adopted.” And, ParkerVision had an opportunity to respond to Intel’s proposed construction by filing its sur-reply, which continued to press for its own claim construction.

However, with regard to patentability (non-obviousness), ParkerVision added in its sur-reply, for the first time, that the cited prior art’s capacitors stored only a negligible amount of energy because “non-negligible” must be measured relative to the available energy of the input EM signal. This part of ParkerVision’s sur-reply was stricken by the Board. ParkerVision’s patent owner response asserted that the cited prior art capacitors must store non-negligible amounts of energy, but did not assert that the reference failed to meet that requirement (instead, merely arguing the capacitors are not part of an energy transfer system). Accordingly, its sur-reply offered a new theory of patentability. There is no abuse of discretion in declining to consider a new theory of patentability raised for the first time in sur-reply.

ParkerVision further asserted that its sur-reply arguments addressed allegedly new arguments in Intel’s reply. But, the Board noted:

[I]f [ParkerVision] believed [Intel’s] Reply raised an issue that was inappropriate for a reply brief or that [ParkerVision] needed a greater opportunity to respond beyond that provided by our Rules (e.g., to include new argument and evidence in its Sur-reply), it was incumbent upon [ParkerVision] to contact [the Board] and request authorization for an exception to the Rules. [ParkerVision] did not do so. [ParkerVision] did not request that its Sur-reply be permitted to include arguments and evidence that would otherwise be impermissible in a sur-reply.

The court faulted ParkerVision for not availing itself of the available procedural mechanisms. For these reasons, the court found no abuse of discretion in the Board’s exclusion of part of ParkerVision’s sur-reply.

Takeaways:

The existence of district court claim construction positions do not guarantee the same claim constructions being adopted by the Board. And, the Federal Circuit reviews claim construction issues de novo.

For the patent owner’s sur-reply, be wary of potentially “new” patentability positions being advanced that were not originally raised in the patent owner response. If any such “new” patentability positions are taken, be cognizant of the procedural mechanism to contact the Board and request authorization for an exception to the Rules to include arguments and/or evidence that may otherwise be impermissible in a sur-reply.

DOCTRINE OF PROSECUTION DISCLAIMER ENSURES THAT CLAIMS ARE NOT CONSTRUED ONE WAY TO GET ALLOWANCE AND IN A DIFFERENT WAY TO AGAINST ACCUSED INFRINGERS

| July 8, 2021

SpeedTrack, Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc. et al.

Decided on June 3, 2021

Prost (author), Bryson, and Reyna

Summary:

The Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s claim construction orders regarding the hierarchical limitations recited in the SpeedTrack’s ’360 patent based on Applicants’ arguments and claim amendments made during the prosecution of the ’360 patent.

Details:

The ’360 patent

SpeedTrack owns U.S. Patent No. 5,544,360 (“the ’360 patent), which is directed to providing “a computer filing system for accessing files and data according to user-designated criteria.” The ’360 patent discusses that prior-art systems “employ a hierarchical filing structure” which could be very cumbersome when the number of files are large or file categories are not well-defined. In addition, the ’360 patent discusses that some prior-art systems are subject to errors when search queries are mistyped and restricted by the field of each data element and the contents of each field.

However, the ’360 patent discloses a method that uses “hybrid” folders, which “contain those files whose content overlaps more than one physical directory,” for providing freedom from the restrictions caused by hierarchical and other computer filing systems.

Representative claim 1 recites a three-step method: (1) creating a category description table containing category descriptions (having no predefined hierarchical relationship with such list or each other); (2) creating a file information directory as the category descriptions are associated with files; and (3) creating a search filter for searching for files using their associated category descriptions.

1. A method for accessing files in a data storage system of a computer system having means for reading and writing data from the data storage system, displaying information, and accepting user input, the method comprising the steps of:

(a) initially creating in the computer system a category description table containing a plurality of category descriptions, each category description comprising a descriptive name, the category descriptions having no predefined hierarchical relationship with such list or each other;

(b) thereafter creating in the computer system a file information directory comprising at least one entry corresponding to a file on the data storage system, each entry comprising at least a unique file identifier for the corresponding file, and a set of category descriptions selected from the category description table; and

(c) thereafter creating in the computer system a search filter comprising a set of category descriptions, wherein for each category description in the search filter there is guaranteed to be at least one entry in the file information directory having a set of category descriptions matching the set of category descriptions of the search filter.

District Court

In September of 2009, SpeedTrack sued retail website operations for infringement of the ’360 patent. The Northern District construed the hierarchical limitation with the below construction (relied in part on disclaimers made during prosecution):

The category descriptions have no predefined hierarchical relationship. A hierarchical relationship is a relationship that pertains to hierarchy. A hierarchy is a structure in which components are ranked into levels of subordination; each component has zero, one, or more subordinates; and no component has more than one superordinate component.

After that, SpeedTrack moved to clarify the district court’s construction regarding prosecution-history disclaimer.

Subsequently, the district court issued a second claim construction order by adding the following clarification in its first order:

Category descriptions based on predefined hierarchical field-and-value relationships are disclaimed. “Predefined” means that a field is defined as a first step and a value associated with data files is entered into the field as a second step. “Hierarchical relationship” has the meaning stated above. A field and value are ranked into levels of subordination if the field is a higher-order description that restricts the possible meaning of the value, such that the value must refer to the field. To be hierarchical, each field must have zero, one, or more associated values, and each value must have at most one associated field.

In order to support its second claim construction order, the district court analyzed SpeedTrack’s prosecution statements (for their clear disavowal of category descriptions based on hierarchical field-and-value relationships).

The Federal Circuit

The CAFC handled the issue of claim construction.

SpeedTrack acknowledged that the hierarchical limitation was added during the prosecution of the ’360 patent to overcome the Schwartz reference.

During the prosecution, Applicants distinguished their invention from Schwartz by arguing that “unlike prior art hierarchical filing systems, the present invention does not require the 2-part hierarchical relationship between fields or attributes, and associated values for such fields or attributes.”

In addition, Applicants argued that “the present invention is a non-hierarchical filing system that allows essentially ‘free-form’ association of category descriptions to files without regard to rigid definitions of distinct fields containing values.”

Finally, Applicants argued that “this distinction has been clarified in the claims as amended by the addition of the following language in all of the claims: ‘each category description comprising a descriptive name, the category descriptions having no predefined hierarchical relationships with such list or each other.’”).

The CAFC agreed with the district court’s assessment that predefined field-and-value relationships are excluded from the claims.

The CAFC disagreed with SpeedTrack’s argument that the “category descriptions” of the ’360 patent are not the fields of Schwartz and that the hierarchical limitation precludes predefined hierarchical relationships only among category descriptions.

SpeedTrack argued that Applicants distinguished Schwartz on other grounds. However, the CAFC did not agree with this argument.

In addition, the CAFC noted that SpeedTrack’s position contradicts its other litigation statements. “Ultimately, the doctrine of prosecution disclaimer ensures that claims are not ‘construed one way in order to obtain their allowance and in a different way against accused infringers.’” Aylus Networks, Inc. v. Apple Inc., 856 F.3d 1353, 1360 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (quoting Southwall Techs., Inc. v. Cardinal IG Co., 54 F.3d 1570, 1576 (Fed. Cir. 1995)).

Finally, the CAFC noted that both of the first and second construction orders acknowledged the disclaimer.

Therefore, the CAFC affirmed the district court’s final judgement of noninfringement.

Takeaway:

- Applicants need to be careful about claim amendments and arguments made during the prosecution of their patents.

- Litigation statements, while not inventors’ prosecution statements and do not demonstrate prosecution-history disclaimer, can strengthen the court’s reasonings on the prosecution history.