Federal Circuit Affirms Alice Nix of Poll-Based Networking System

| August 10, 2023

Trinity Info Media v Covalent, Inc.

Decided: July 14, 2023

Before Stoll, Bryson and Cunningham.

Summary:

The Federal Circuit affirmed patent ineligibility of the Trinity’s poll-based networking system under Alice. The claims are directed to the abstract idea of matching based on questioning, something that a human can do. The additional features of a data processing system, computer system, web server, processor(s), memory, hand-held device, mobile phone, etc. are all generic components providing a technical environment for performing the abstract idea and do not detract from the focus of the claims being on the abstract idea. The specification also does not support a finding that the claims are directed to a technological improvement in computers, mobile phones, computer systems, etc.

Procedural History:

Trinity sued Covalent for infringing US Patent Nos. 9,087,321 and 10,936,685 in 2021. The district court granted Covalent’s 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss, concluding that the asserted claims are not patent eligible subject matter under 35 USC §101. Trinity appealed.

Decision:

Representative claim 1 from the ‘321 patent is as follows:

A poll-based networking system, comprising:

a data processing system having one or more processors and a memory, the memory being specifically encoded with instructions such that when executed, the instructions cause the one or more processors to perform operations of:

receiving user information from a user to generate a unique user profile for the user;

providing the user a first polling question, the first polling question having a finite set of answers and a unique identification;

receiving and storing a selected answer for the first polling question;

comparing the selected answer against the selected answers of other users, based on the unique identification, to generate a likelihood of match between the user and each of the other users; and

displaying to the user the user profiles of other users that have a likelihood of match within a predetermined threshold.

Representative claim 2 from the ‘685 patent is as follows:

A computer-implemented method for creating a poll-based network, the method comprising an act of causing one or more processors having an associated memory specifically encoded with computer executable instruction means to execute the instruction means to cause the one or more processors to collectively perform operations of:

receiving user information from a user to generate a unique user profile for the user;

providing the user one or more polling questions, the one or more polling ques-tions having a finite set of answers and a unique identification;

receiving and storing a selected answer for the one or more polling questions;

comparing the selected answer against the selected answers of other users, based on the unique identification, to generate a likelihood of match between the user and each of the other users;

causing to be displayed to the user other users, that have a likelihood of match within a predetermined threshold;

wherein one or more of the operations are carried out on a hand-held device; and

wherein two or more results based on the likelihood of match are displayed in a list reviewable by swiping from one result to another.

Looking at the claims first, the claimed functions of (1) receiving user information; (2) providing a polling question; (3) receiving and storing an answer; (4) comparing that answer to generate a “likelihood of match” with other users; and (5) displaying certain user profiles based on that likelihood are all merely collecting information, analyzing it, and displaying certain results which fall in the “familiar class of claims ‘directed to’ a patent ineligible concept,” which a human mind could perform. The court agreed with the district court’s finding that these claims are directed to an abstract idea of matching based on questioning.

The ‘685 patent adds the further function of reviewing matches using swiping and a handheld device. These features did not alter the court’s decision. The dependent claims also added other functional variations, such as performing matching based on gender, varying the number of questions asked, displaying other users’ answers, etc. These are all trivial variations that are themselves abstract ideas. The further recitation of the hand-held device, processors, web servers, database, and a “match aggregator” did not change the “focus” of the asserted claims. Instead, such generic computer components were merely limitations to a particular environment, which did not make the claims any less abstract for the Alice/Mayo Step 1.

With regard to software-based inventions, the Alice/Mayo Step 1 inquiry “often turns on whether the claims focus on the specific asserted improvement in computer capabilities or, instead, on a process that qualifies as an abstract idea for which computers are invoked merely as a tool.” In addressing this, the court looks at the specification’s description of the “problem facing the inventor.” Here, the specification framed the inventor’s problem as how to improve existing polling systems, not how to improve computer technology. As such, the specification confirms that the invention is not directed to specific technological solutions, but rather, is directed to how to perform the abstract idea of matching based on progressive polling.

Under Alice/Mayo Step 2, the claimed use of general-purpose processors, match servers, unique identifications and/or a match aggregator is merely to implement the underlying abstract idea. The specification describes use of “conventional” processors, web servers, the Internet, etc. The court has “ruled many times” that “invocations of computers and networks that are not even arguably inventive are insufficient to pass the test of an inventive concept in the application of an abstract idea.” And, no inventive concept is found where claims merely recite “generic features” or “routine functions” to implement an underlying abstract idea.

Trinity’s Argument 1

Claim construction and fact discovery was necessary, but not done, before analyzing the asserted claims under §101.

Federal Circuit’s Response 1

“A patentee must do more than invoke a generic need for claim construction or discovery to avoid grant of a motion to dismiss under § 101. Instead, the patentee must propose a specific claim construction or identify specific facts that need development and explain why those circumstances must be resolved before the scope of the claims can be understood for § 101 purposes.”

Trinity’s Argument 2

Under Alice/Mayo Step One, the claims included an “advance over the prior art” because the prior art did not carry out matching on mobile phones, did not employ “multiple match servers” and did not employ “match aggregators.”

Federal Circuit’s Response 2

A claim to a “new” abstract idea is still an abstract idea.

Trinity’s Argument 3

Humans cannot mentally engage in the claimed process because humans could not perform “nanosecond comparisons” and aggregate “result values with huge numbers of polls and members” nor could humans select criteria using “servers, storage, identifiers, and/or thresholds.”

Federal Circuit’s Response 3

The asserted claims do not require “nanosecond comparisons” nor “huge numbers of polls and members.”

Trinity’s claims can be directed to an abstract idea even if the claims require generic computer components or require operations that a human cannot perform as quickly as a computer. Compare, for example, with Electric Power Group, where the court held the claims to be directed to an abstract idea even though a human could not detect events on an interconnected electric power grid in real time over a wide area and automatically analyze the events on that grid. Likewise, in ChargePoint (electric car charging network system), claims directed to enabling “communication over a network” were abstract ideas even though a human could not communicate over a computer network without the use of a computer.

Trinity’s Argument 4

Claims are eligible inventions directed to improvements to the functionality of a computer or to a network platform itself.

Federal Circuit’s Response 4

As described in the specification, mere generic computer components, e.g., a conventional computer system, server, web server, data processing system, processors, memory, mobile phones, mobile apps, are used. Such generic computer components merely provide a generic technical environment for performing an abstract idea. The specification does not describe the invention of swiping or improving on mobile phones. Indeed, the ‘685 patent describes the “advent of the internet and mobile phones” as allowing the establishment of a “plethora” or “mobile apps.” As such, “the specification does not support a finding that the claims are directed to a technological improvement in computer or mobile phone functionality.”

Trinity’s Argument 5

The district court failed to properly consider the comparison of selected answers against other uses “based on the unique identification” which was a “non-traditional design” that allowed for “rapid comparison and aggregation of result values even with large numbers of polls and members.”

Federal Circuit’s Response 5

Use of a “unique identifier” does not render an abstract idea any less abstract.

On the other hand, the “non-traditional design” appears to be based on use of an “in-memory, two-dimensional array” that “provides for linear speed across multiple match servers” and permits “an immediate comparison to determine if the user had the same answer to that of another user.” However, the asserted claims do not require any such in-memory, two-dimensional array.

Trinity’s Argument 6

The district court failed to properly consider the generation of a likelihood of a match “within a predetermined threshold.” Without this consideration, “there would be no limit or logic associated with the volume or type of results a user would receive.”

Federal Circuit’s Response 6

This merely addresses the kind of data analysis that the abstract idea of matching would include, namely how many answers should be the same before declaring a match. This does not change the focus of the claimed invention from the abstract idea of matching based on questioning.

Trinity’s Argument 7

There is an inventive concept under Alice/Mayo Step 2 because the claims recite steps performed in a “non-traditional system” that can “rapidly connect multiple users using progressive polling that compare[s] answers in real time based on their unique identification (ID) (and in the case of the ’685 patent employ swiping)” which “represents a significant advance over the art.”

Federal Circuit’s Response 7

These conclusory assertions are insufficient to demonstrate an inventive concept. “We disregard conclusory statements when evaluating a complaint under Rule 12(b)(6).”

Takeaways:

The evisceration of software-related inventions as abstract ideas continues. Although the court looks at the “claimed advance over the prior art” in assessing the “directed to” inquiry under Alice Step 1, conclusory assertions of advances over the prior art are insufficient to demonstrate inventive concept under Alice Step 2, at least for a 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss. It remains to be seen what type of description of an “advance over the prior art” would not be “conclusory” and satisfy the “significantly more” inquiry to be an inventive concept under Alice Step 2.

The one glimmer of hope for the patentee might have been the use of an “in-memory, two-dimensional array” that “provides for linear speed across multiple match servers.” An example of patent eligibility based on use of such logical structures can be found in Enfish. However, if the specification does not describe this use of an in-memory two-dimensional array and the “technological” improvement resulting therefrom to be the “focus” of the invention, even this feature might not be enough to survive § 101.

Limitations of Result-Based Functional Language and Generic Computer Components in Patent Eligibility

| May 2, 2023

Hawk Technology Systems, Llc V. Castle Retail, LLC

Before REYNA, HUGHES, and CUNNINGHAM, Circuit Judges.

Summary

The district court granted Castle Retail’s motion, finding that the patent claims were directed towards the abstract idea of storing and displaying video without providing an inventive step to transform the abstract idea into a patent-eligible invention. The district court dismissed Hawk’s case, and Hawk appealed. The Federal Circuit upheld the district court’s decision, affirming that the patent claims were invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

Background

Hawk Technology Systems is the owner of a US Patent No. 10,499,091 ( the ’91 patent) entitled “High-Quality, Reduced Data Rate Streaming Video Product and Monitoring System.” The patent was filed in 2017 and granted in 2019, with priority claimed back to 2002. It describes a technique for displaying multiple stored video images on a remote viewing device in a video surveillance system, using a configuration that utilizes existing broadband infrastructure and a generic PC-based server to transmit signals from cameras as streaming sources at low data rates and variable frame rates. The patent claims that this approach reduces costs, minimizes memory storage requirements, and enhances bandwidth efficiency.

Hawk Technology Systems sued Castle Retail for patent infringement in Tennessee, alleging that Castle Retail’s use of security surveillance video operations in its grocery stores infringed on Hawk’s patent. Castle Retail moved to dismiss the case, arguing that the patent claims were invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 101, as they were directed towards ineligible subject matter.

The ‘091 patent contains six claims, but the appellant, Hawk Technology Systems, did not assert that there was any significant difference between the claims regarding eligibility. As a result, claim 1 was selected as representative, which recites:

1. A method of viewing, on a remote viewing device of a video surveillance system, multiple simultaneously displayed and stored video images, comprising the steps of:

receiving video images at a personal computer based system from a plurality of video sources, wherein each of the plurality of video sources comprises a camera of the video surveillance system;

digitizing any of the images not already in digital form using an analog-to-digital converter;

displaying one or more of the digitized images in separate windows on a personal computer based display device, using a first set of temporal and spatial parameters associated with each image in each window;

converting one or more of the video source images into a selected video format in a particular resolution, using a second set of temporal and spatial parameters associated with each image;

contemporaneously storing at least a subset of the converted images in a storage device in a network environment;

providing a communications link to allow an external viewing device to access the storage device;

receiving, from a remote viewing device remoted located remotely from the video surveillance system, a request to receive one or more specific streams of the video images;

transmitting, either directly from one or more of the plurality of video sources or from the storage device over the communication link to the remote viewing device, and in the selected video format in the particular resolution, the selected video format being a progressive video format which has a frame rate of less than substantially 24 frames per second using a third set of temporal and spatial parameters associated with each image, a version or versions of one or more of the video images to the remote viewing device, wherein the communication link traverses an external broadband connection between the remote computing device and the network environment; and

displaying only the one or more requested specific streams of the video images on the remote computing device.

In September 2021, the district court granted Castle Retail’s motion to dismiss the case. The court found that the claims in Hawk’s ‘091 patent failed the two-part Alice test. The court determined that the ‘091 patent is directed to an abstract idea of a method for storing and displaying video, and that the claimed elements are generic computer elements without any technological improvement.

Hawk’s argument that the temporal and spatial parameters are the inventive concept was also rejected, as the claims and specification failed to explain what those parameters are or how they should be manipulated. The district court also found that the claimed “analog-to-digital converter” and “personal computer based system” were not technological improvements, but rather generic computer elements. Additionally, it determined that the “parameters and frame rate” defined in the claims and specification did not appear to be more than manipulating data in a way that has been found to be abstract.

The district court concluded that the claims can be implemented using off-the-shelf, conventional computer technology and entered judgment against Hawk. Hawk appealed the decision.

Discussion

The Federal Circuit applied Alice step one in this case to determine if the ’091 patent claims were directed to an abstract idea. They agreed with the district court’s conclusion that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of “storing and displaying video.”

The Federal Circuit further clarified that the claims are directed to a method of receiving, displaying, converting, storing, and transmitting digital video “using result-based functional language.” Two-Way Media Ltd. v. Comcast Cable Commc’ns, LLC, 874 F.3d 1329, 1337 (Fed. Cir. 2017). The claims require various functional results of “receiving video images,” “digitizing any of the images not already in digital form,” “displaying one or more of the digitized images,” “converting one or more of the video source images into a selected video format,” “storing at least a subset of the converted images,” “providing a communications link,” “receiving . . . a request to receive one or more specific streams of the video images,” “transmitting . . . a version of one or more of the video images,” and “displaying only the one or more requested specific streams of the video images.”

Hawk argued that the ’091 patent claims were not directed to an abstract idea but to a specific technical problem and solution related to maintaining full-bandwidth resolution while providing professional quality editing and manipulation of digital video images. However, this argument failed because the Federal Circuit found that the claims themselves did not disclose how the alleged goal was achieved and that converting information from one format to another is an abstract idea. Furthermore, the claims did not recite a specific solution to make the alleged improvement concrete and, at most, recited abstract data manipulation. Therefore, the ’091 patent claims lacked sufficient recitation of how the purported invention improved the functionality of video surveillance systems and amounted to a mere implementation of an abstract idea.

At Alice step two, the claim elements were examined individually and as a combination to determine if they transformed the claim into a patent-eligible application of the abstract idea. The district court found that the claims did not show a technological improvement in video storage and display and that the limitations could be implemented using generic computer elements.

Hawk argued that the claims provided an inventive solution that achieved the benefit of transmitting the same digital image to different devices for different purposes while using the same bandwidth, citing specific tools, parameters, and frame rates. The Federal Circuit acknowledged that the claims mentioned “parameters.” However, the claims did not specify what these parameters were, and at most they pertained to abstract data manipulation such as image formatting and compression. Hawk did not contest that the claims involved conventional components to carry out the method. The Federal Circuit also noted that the ‘091 patent affirmed that the invention was meant to “utilize” existing broadband media and other conventional technologies. Thus, the Federal Circuit found that there is nothing inventive in the ordered combination of the claim limitations and noted that Hawk has not pointed to anything inventive.

The Federal Circuit determined that the claims in the ‘091 patent did not transform the abstract concept into something substantial and therefore did not pass the second step of the Alice test. As a result, the Federal Circuit concluded that the ‘091 patent is ineligible since its claims address an abstract idea that was not transformed into eligible subject matter.

Takeaway

- Reciting an abstract idea performed on a set of generic computer components does not contain an inventive concept.

- Claims that use result-based functional language in combination with generic computer components may not be sufficient to transform an abstract idea into patent-eligible subject matter.

MERE AUTOMATION OF MANUAL PROCESSES USING GENERIC COMPUTERS DOES NOT CONSTITUTE A PATENTABLE IMPROVEMENT IN COMPUTER TECHNOLOGY

| December 6, 2022

International Business Machines Corporation v. Zillow Group, Inc., Zillow, Inc.

Decided: October 17, 2022

Hughes (author), Reyna, and Stoll (dissenting in parts)

Summary:

In 2019, IBM sued Zillow for infringement of several patents related to graphical display technology in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington. Zillow filed a motion for judgment on the pleadings, arguing that the claims of IBM’s asserted patents were patent ineligible under § 101. The district court granted Zillow’s motion as to two IBM patents because they were directed to abstract ideas with no inventive concept. The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court decision and therefore, affirmed.

Details:

Two asserted IBM patents are U.S. Patent Nos. 9,158,789 (“the ’789 patent”) and 7,187,389 (“the ’389 patent”).

The ’789 patent

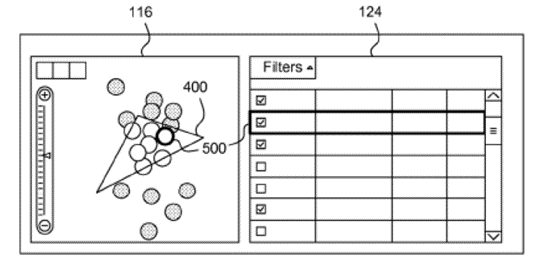

This patent describes a method for “coordinated geospatial, list-based and filter-based selection.” Here, a user draws a shape on a map to select that area of the map, and the claimed system then filters and displays data limited to that area of the map.

Claim 8 is a representative claim:

A method for coordinated geospatial and list-based mapping, the operations comprising:

presenting a map display on a display device, wherein the map display comprises elements within a viewing area of the map display, wherein the elements comprise geospatial characteristics, wherein the elements comprise selected and unselected elements;

presenting a list display on the display device, wherein the list display comprises a customizable list comprising the elements from the map display;

receiving a user input drawing a selection area in the viewing area of the map display, wherein the selection area is a user determined shape, wherein the selection area is smaller than the viewing area of the map display, wherein the viewing area comprises elements that are visible within the map display and are outside the selection area;

selecting any unselected elements within the selection area in response to the user input drawing the selection area and deselecting any selected elements outside the selection area in response to the user input drawing the selection area; and

synchronizing the map display and the list display to concurrently update the selection and deselection of the elements according to the user input, the selection and deselection occurring on both the map display and the list display.

The ’389 patent

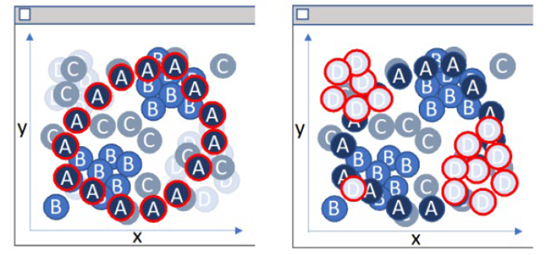

This patent describes methods of displaying layered data on a spatially oriented display based on nonspatial display attributes (i.e., displaying objects in visually distinct layers). Here, objects in layers of interest could be emphasized while other layers could be deemphasized.

Claim 1 is a representative claim:

A method of displaying layered data, said method comprising:

selecting one or more objects to be displayed in a plurality of layers;

identifying a plurality of non-spatially distinguishable display attributes, wherein one or more of the non-spatially distinguishable display attributes corresponds to each of the layers;

matching each of the objects to one of the layers;

applying the non-spatially distinguishable display attributes corresponding to the layer for each of the matched objects;

determining a layer order for the plurality of layers, wherein the layer order determines a display emphasis corresponding to the objects from the plurality of objects in the corresponding layers; and

displaying the objects with the applied non-spatially distinguishable display attributes based upon the determination, wherein the objects in a first layer from the plurality of layers are visually distinguished from the objects in the other plurality of layers based upon the non-spatially distinguishable display attributes of the first layer.

Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit reviewed the grant of a Rule 12 motion under the law of the regional circuit (de novo for the Ninth Circuit).

As for Alice step one analysis of the ’789 patent, the Federal Circuit held that the claims fail to recite any inventive technology for improving computers as tools, and instead directed to “an abstract idea for which computers are invoked merely as a tool.”

The Federal Circuit further held that identifying, analyzing, and presenting any data to a user is not an improvement specific to computer technology, and that mere automation of manual processes using generic computers is not a patentable improvement in computer technology.

The Federal Circuit held that this patent describes functions (presenting, receiving, selecting, synchronizing) without explaining how to accomplish these functions.

As for Alice step two analysis of the ’789 patent, the Federal Circuit noted that IBM has not made any allegations that any features of the claims is inventive. Instead, the Federal Circuit held that the limitations in this patent simply describe the abstract method without providing more.

As for Alice step one analysis of the ’389 patent, the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that this patent is directed to the abstract idea of organizing and displaying visual information (merely organize and arrange sets of visual information into layers and present the layers on a generic display device).

The Federal Circuit held that like the ’789 patent, this patent describes various functions without explaining how to accomplish any of them.

The Federal Circuit further held that the problem this patent tries to solve is not even specific to a computing environment, and the solution that this patent provides could be accomplished using colored pencils and translucent paper.

As for Alice step two analysis of the ’389 patent, the Federal Circuit noted that dynamic re-layering or rematching could also be done by hand (slowly), and that any of the patent’s improved efficiency does not come from an improvement in the computer but from applying the claimed abstract idea to a computer display.

Therefore, the Federal Circuit held that there is no inventive concept that transforms the abstract idea of organizing and displaying visual information into a patent-eligible application of that abstract idea.

Dissent by Stoll

Judge Stoll agreed with the majority opinion. However, she did not agree with the majority opinion that claims 9 and 13 of the ’389 patent are not patent eligible.

The information handling system as described in claim 8 further comprising:

a rearranging request received from a user;

rearranging logic to rearrange the displayed layers, the rearranging logic including:

re-matching logic to re-match one or more objects to a different layer from the plurality of layers;

application logic to apply the non-spatially distinguishable display attributes corresponding to the different layer to the one or more re-matched objects; and

display logic to display the one or more rematched objects.

She noted that in combination with factual allegations in the complaint (problems with the conventional technology with larger and complex data systems) and the expert declaration, the claimed relaying and rematching steps are directed to a technical improvement in how a user interacts with a computer with the GUI.

Takeaway:

- The argument that the claimed invention improves a user’s experience while using a generic computer is not sufficient to render the claims patent eligible at Alice step one analysis.

- Identifying, analyzing, and presenting certain data to a user is not an improvement specific to computing technology itself (mere automation of manual processes using generic computers not sufficient).

- The specification should be drafted to explain how to accomplish the required functions instead of merely describing them (avoid “result-based functional language”).

Tags: 35 U.S.C. §101 > Alice > patent eligible subject matter > patent ineligible subject matter

Throwing in Kitchen Sink on 101 Legal Arguments Didn’t Help Save Patent from Alice Ax

| November 21, 2022

In Re Killian

Taranto, Clevenger, Chen (August 23, 2022).

Summary:

Killian’s claim to “determining eligibility for Social Security Disability Insurance [SSDI] benefits through a computer network” was deemed “clearly patent ineligible in view of our precedent.” However, the Federal Circuit also disposes of a host of the appellant’s legal challenges to 101 jurisprudence, including:

(A) all court and Board decisions finding a claim patent ineligible under Alice/Mayo is arbitrary and capricious under the APA;

(B) comparing this case to other cases in which this court and the Supreme Court considered issues of patent eligibility under 101 violates the appellant’s due process rights because Mr. Killian had no opportunity to appear in those other cases;

(C) the search for an “inventive concept” at Alice Step 2 is improper because Congress did away with an “invention” requirement when it enacted the Patent Act of 1952;

(D) “mental steps” ineligibility has no foundation in modern patent law; and

(E) there is no substantial evidence to support the rejections in view of the PTAB’s “evidentiary vacuum” in assessing the factual inquiry into whether the claimed process is well-understood, routine, and conventional.

Procedural History:

The PTAB’s affirmance of the examiner’s final rejection of Killian’s US Patent Application No. 14/450,024 under 35 USC §101 was appealed to the Federal Circuit and was upheld.

Decision:

Representative claim 1 is as follows:

A computerized method for determining eligibility for social security disability insurance (SSDI) benefits through a computer network, comprising the steps of:

(a) providing a computer processing means and a computer readable media;

(b) providing access to a Federal Social Security database through the computer network, wherein the Federal Social Security database provides records containing information relating to a person’s status of SSDI and/or parental and/or marital information relating to SSDI benefit eligibility;

(c) selecting at least one person who is identified as receiving treatment for developmental disabilities and/or mental illness;

(d) creating an electronic data record comprising information relating to at least the identity of the person and social security number, wherein the electronic data record is recorded on the computer readable media;

(e) retrieving the person’s Federal Social Security record containing information relating to the person’s status of SSDI benefits;

(f) determining whether the person is receiving SSDI benefits based on the SSDI status information contained within the Federal Social Security database record through the computer network; and

(g) indicating in the electronic data record whether the person is receiving SSDI benefits or is not receiving SSDI benefits.

The court agreed with the PTAB that the thrust of this claim is “the collection of information from various sources (a Federal database, a State database, and a caseworker) and understanding the meaning of that information (determining whether a person is receiving SSDI benefits and determining whether they are eligible for benefits under the law).” Collecting information and “determining” whether benefits are eligible are mental tasks humans routinely do. That these steps are performed on a generic computer or “through a computer network” does not save these claims from being directed to an abstract idea under Alice step 1. Under Alice step 2, this is merely reciting an abstract idea and adding “apply it with a computer.” The claims do not recite any technological improvement in how a computer goes about “determining” eligibility for benefits. Merely comparing information against eligibility requirements is what humans seeking benefits would do with or without a computer.

The court also addresses appellant’s further challenges (A)-(E) as follows.

- all court and Board decisions finding a claim patent ineligible under Alice/Mayo is arbitrary and capricious under the APA

The standards of review in the APA do not apply to decisions by courts. The APA governs judicial review of “agency action.”

There was also an assertion that there is a Fifth Amendment Due Process Clause violation stemming from the imprecision of the Alice/Mayo standard. However, the court noted that Killian never argued that the Alice/Mayo standard runs afoul of the “void-for-vagueness doctrine” and could not have argued this because this case was not even a close call (vagueness as applied to the particular case is a prerequisite to establishing facial vagueness).

As for Board decisions finding patents ineligible as being arbitrary and capricious under the APA, “we may not announce that the Board acts arbitrarily and capriciously merely by applying binding judicial precedent.” This would be akin to using the APA to attack the Supreme Court’s interpretations of 101. However, “the APA does not empower us to review decisions of ‘the courts of the United States’ because they are not agencies.”

Mr. Killian also requested “a single non-capricious definition or limiting principle” for “abstract idea” and “inventive concept.” However, the court points out that there is “no single, hard-and-fast rule that automatically outputs an answer in all contexts” because there are different types of abstract ideas (mental processes, methods of organizing human activity, claims to results rather than a means of achieving the claimed result). Nevertheless, guidance has been provided (citing several cases).

And even if the Alice/Mayo framework is unclear, “both this court and the Board would still be bound to follow the Supreme Court’s §101 jurisprudence as best we can as we must follow the Supreme Court’s precedent unless and until it is overruled by the Supreme Court.”

- comparing this case to other cases in which this court and the Supreme Court considered issues of patent eligibility under 101 violates the appellant’s due process rights because Mr. Killian had no opportunity to appear in those other cases

Examination of and comparison to earlier caselaw is just classic common law methodology for deciding cases arising under 101. “Nothing stops Mr. Killian from identifying any important distinctions between his claimed invention and claims we have analyzed in prior cases.”

- the search for an “inventive concept” at Alice Step 2 is improper because Congress did away with an “invention” requirement when it enacted the Patent Act of 1952

First, Killian has not established that Alice Step 2’s “inventive concept” is the same thing as the “invention” requirement in the Patent Act of 1952. It is not. For instance, there is no requirement to ascertain the “degree of skill and ingenuity” possessed by one of ordinary skill in the art under Alice Step 2. In any event, the Supreme Court required the “inventive concept” inquiry at Step 2, and so, “search for an inventive concept we must.”

- “mental steps” ineligibility has no foundation in modern patent law

“This argument is plainly incorrect” (citing Benson, Mayo, Diehr, Bilski, etc.). “[W]e are bound by our precedential decisions holding that steps capable of performance in the human mind are, without more, patent-ineligible abstract ideas.”

- there is no substantial evidence to support the rejections in view of the PTAB’s “evidentiary vacuum” in assessing the factual inquiry into whether the claimed process is well-understood, routine, and conventional

Substantial evidence supported the PTAB’s decision regarding Alice Step 2. The additional elements of a computer processor and a computer readable media are generic, as the application itself admits (the PTAB cited to the specification’s description about how the claimed method “may be performed by any suitable computer system”). And, the claimed “creating an electronic data record,” “indicating in the electronic data record whether the person is receiving SSDI adult child benefits,” “providing a caseworker display system,” “generating a data collection input screen,” “indicating in the electronic data record whether the person is eligible for SSDI adult child benefits,” and other data tasks are merely selection and manipulation of information – are not a transformative inventive concept.

Mr. Killian also refers to 55 documents allegedly presented to the examiner and the PTAB. But, because these were not included in the joint appendix and nothing is explained on appeal as to what these 55 documents show, “Mr. Killian forfeited any argument on appeal based on those fifty-five documents by failing to present anything more than a conclusory, skeletal argument.”

Takeaways:

Given the continued dissatisfaction over the court’s eligibility guidance and the frustration over the Supreme Court’s refusal to take on §101 since Alice, this decision offers a rare insight into the court’s position on various §101 legal challenges. For instance, this decision appears to suggest a potential Fifth Amendment Due Process Clause violation stemming from the imprecision of the Alice/Mayo standard, but only for a “close call” case where vagueness can be established for the particular case, in order to challenge the facial vagueness of the Alice/Mayo standard under the “void-for-vagueness doctrine.”

Detecting Natural Phenomena Using Conventional Techniques Found “Directed to” Natural Phenomena at Alice/Mayo Step One

| September 16, 2022

CAREDX, INC. v. NATERA, INC.

Lourie, Bryson, and Hughes. Opinion by Lourie.

Summary

The CAFC held that genetic diagnostic method claims are ineligible for patent, finding that the claims reciting conventional laboratory techniques to perform diagnosis using a naturally occurring correlation are directed to natural phenomena under Alice/Mayo step one, and also lack additional elements to constitute enough inventive concept under Alice/Mayo step two.

Details

CareDx sued Natera and Eurofins in the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware, asserting that their products infringed one or more patents licensed to CareDx. The district court awarded summary judgment for the defendants, holding that the patents are ineligible for patent under 35 U.S.C. §101. CareDx appealed the district court’s grant of the summary judgment motions of ineligibility.

The patents at issue, U.S. Patents 8,703,652, 9,845,497, and 10,329,607, relate to diagnosis of organ transplant status by detecting a donor’s cell-free DNA (“cfDNA”) circulating in a recipient’s body. The specification, common to all three patents, depicts prior findings that the existence of cfDNA in blood is mostly attributed to dead cells, and had been used for various diagnostic purposes, such as cancer diagnostics and prenatal testing. The specification notes that the cfDNA-based diagnostic scheme is applicable to organ transplant situations, where the recipient’s immune system kills incompatible donor’s cells which in turn release their nucleic acids into the recipient’s stream, such that an increased level of the donor-derived cfDNA may allow for detection of the transplant rejection.

Claim 1 of ‘652 patent recites:

1. A method for detecting transplant rejection, graft dysfunction, or organ failure, the method comprising:

(a) providing a sample comprising cell-free nucleic acids from a subject who has received a transplant from a donor;

(b) obtaining a genotype of donor-specific polymorphisms or a genotype of subject-specific polymorphisms, or obtaining both a genotype of donor-specific polymorphisms and subject-specific polymorphisms, to establish a polymorphism profile for detecting donor cell-free nucleic acids, wherein at least one single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) is homozygous for the subject if the genotype comprises subject-specific polymorphisms comprising SNPs;

(c) multiplex sequencing of the cell-free nucleic acids in the sample followed by analysis of the sequencing results using the polymorphism profile to detect donor cell-free nucleic acids and subject cell-free nucleic acids; and

(d) diagnosing, predicting, or monitoring a transplant status or outcome of the subject who has received the transplant by determining a quantity of the donor cell-free nucleic acids based on the detection of the donor cell-free nucleic acids and subject cell-free nucleic acids by the multiplexed sequencing, wherein an increase in the quantity of the donor cell-free nucleic acids over time is indicative of transplant rejection, graft dysfunction or organ failure, and wherein sensitivity of the method is greater than 56% compared to sensitivity of current surveillance methods for cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV).

The representative claims of the three patents recite somewhat similar procedures, which may be summarized as:

- collecting a bodily sample from the recipient,

- “genotyping” or identifying genetic features that allow for distinction between the donor and recipient,

- “sequencing” or determining the makeup of cfDNA included in the sample, and

- determining, using the genetic features, the amount of cfDNA originating from the donor in the sample.

The specification depicts that the methods are performed using specific techniques that are “standard,” “well-established” and/or reported in prior patents and scientific articles, including sophisticated polymerase chain reaction (“PCR”), such as digital PCR and selective amplification, and next-generation sequencing (“NGS”), all of which are advanced, but already known, techniques in the field.

The district court held that that the asserted claims were patent ineligible as they were “directed to the detection of natural phenomena, specifically, the presence of donor cfDNA in a transplant recipient and the correlation between donor cfDNA and transplant rejection” and also, “recited only conventional techniques.”

On appeal, the CAFC performed the two-step Alice/Mayo analysis to determine patent-eligibility.

- Are the claims “directed to” laws of nature or natural phenomena? – Yes.

CareDx sought to characterize the claimed invention as directed to “improved measurement methods,” in particular, patent-eligible “use of digital PCR, NGS, and selective amplification” allowing for improved accuracy in cfDNA measurement, as opposed to “discovery of a natural correlation between organ rejection and the donor’s cfDNA levels in the recipient’s blood.” CareDx also asserted that the district court improperly considered conventionality of the claimed techniques at step one, essentially merging the two steps into a single-step analysis centered on conventionality.

The CAFC found that the claims satisfy the step one. Two contrasting precedents are notable: Illumina, Inc. v. Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc., 952 F.3d 1367, opinion modified by 967 F.3d 1319, 1327 (Fed. Cir. 2020), and Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc. v. Sequenom, Inc., 788 F.3d 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2015). The CAFC noted that this case is different from Illumina, where the claimed improvement was a patent-eligible “method for preparing” a cfDNA fraction that would not occur naturally without manipulation of a starting sample; rather, the asserted claims are akin to those in Ariosa, wherein the claimed diagnostic methods, including the steps of “amplifying” (i.e., making many copies of) a cfDNA sample using PCR and “detecting” a certain type of cfDNA, so as to perform diagnosis using a natural correlation between certain conditions and the level of cfDNA, were found to be “directed to a natural phenomenon.”

The CAFC noted that the conventionally considerations are not limited to step two, and precedents have routinely performed overlapping conventionality inquiry at both stages of Alice/Mayo. The CAFC found that the use of specific laboratory techniques relied on by CareDx only amounts to “conventional use of existing techniques to detect naturally occurring cfDNA.” The CAFC added that the conventionality is supported by the specification’s numerous remarks characterizing the claimed techniques as “any suitable method known in the art” and similar boilerplate language.

- Do the claims recite additional elements, aside from the natural phenomena, which transform the nature of the claim’ into a patent-eligible application? – No.

CareDx’s main argument at step two was that the inventive concept resides in the use of the specific advanced techniques to identify and measure donor-derived cfDNA.

The CAFC disagreed, concluding that the claimed methods lack requisite inventive concept. In reaching the conclusion, the CAFC again pointed to the specification’s admissions of the conventionality of the individual techniques recited in the claims. The CAFC went on to state that “[t]he specification confirms that the claimed combination of steps … was a straightforward, logical, and conventional method for detecting cfDNA previously used in other contexts,” which adds nothing inventive to the detection of natural phenomena.

Takeaway

This case provides a reminder that conventionality of claimed elements may affect both steps of Alice/Mayo test. At step one, the effort to characterize the claim as being “directed to” a patent-eligible subject matter can be thwarted where the claimed elements are undisputedly conventional, in the absence of an unconventional element that is not a judicial exception to eligibility. And at step two, the conventionality of the individual elements and their combination prohibits finding of inventive concept.

Authentication method held patent-eligible at Alice Step Two

| October 14, 2021

CosmoKey Solutions GmbH & Co. v. Duo Security LLC

Decided on October 4, 2021

O’Malley, Reyna, and Stoll. Court opinion by Stoll. Concurring opinion by Reyna.

Summary

The United States District Court for the District of Delaware granted Duo’s motion for judgment on the pleadings under Rule 12(c), arguing that all claims of the patent in dispute are ineligible under 35 U.S.C. 101 as the claims are directed to the abstract idea of authentication and do not recite any patent-eligible inventive concept. On appeal, the Federal Circuit unanimously revered the district court decision, holding that the claims of the patent are patent-eligible under Alice Step Two because they recite a specific improvement to a particular computer-implemented authentication technique. Reyna concurred, arguing that he would resolve the dispute at Alice Step One, not Step Two.

Details

I. Background

(1) Patent in Dispute

CosmoKey Solutions GmbH & Co. (“CosmoKey’s”) owns U.S. Patent No. 9,246,903 (“the ’903 patent”), titled “Authentication Method” and purported to disclose an authentication method that is both low in complexity and high in security.

Claim 1 is the only independent claim of the ’903 patent and reads:

1. A method of authenticating a user to a transaction at a terminal, comprising the steps of:

transmitting a user identification from the terminal to a transaction partner via a first communication channel,

providing an authentication step in which an authentication device uses a second communication channel for checking an authentication function that is implemented in a mobile device of the user, as a criterion for deciding whether the authentication to the transaction shall be granted or denied, having the authentication device check whether a predetermined time relation exists between the transmission of the user identification and a response from the second communication channel,

ensuring that the authentication function is normally inactive and is activated by the user only preliminarily for the transaction,

ensuring that said response from the second communication channel includes information that the authentication function is active, and

thereafter ensuring that the authentication function is automatically deactivated.

(2) The District Court

CosmoKey brought a civil lawsuit against Duo Security, Inc. (“Duo”) for infringement of the ’903 patent at the United States District Court for the District of Delaware (“the district court”). Duo moved for judgment on the pleadings pursuant to Rule 12(c) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, arguing that the claims of the ’903 patent are ineligible under 35 U.S.C. 101.

The district court agreed with Duo, holding that the patent claims were invalid. The district court reasoned that the claims “are directed to the abstract idea of authentication—that is, the verification of identity to permit access to transactions” at Alice Step One, and that “the [’]903 patent merely teaches generic computer functionality to perform the abstract concept of authentication; and it therefore fails Alice’s step two inquiry.” In so holding, the district court determined that the patent itself admits that “the detection of an authentication function’s activity and the activation by users of an authentication function within a predetermined time relation were well-understood and routine, conventional activities previously known in the authentication technology field.”

CosmoKey appealed the district court’s judgment.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit (“the Court”) unanimously revered the district court decision, holding that the claims of the patent are patent-eligible under Alice step two.

Before discussing Alice Steps One and Two, the Court referred to several cases in which the Court has previously considered the eligibility of various claims generally directed to authentication and verification under § 101. However, the Court compared the claims of the ’903 patent with none of those claims held patent-eligible or patent-ineligible. See Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., 822 F.3d 1327, 1334 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (“The Supreme Court has not established a definitive rule to determine what constitutes an “abstract idea” sufficient to satisfy the first step of the Mayo/Alice inquiry. … Rather, both this court and the Supreme Court have found it sufficient to compare claims at issue to those claims already found to be directed to an abstract idea in previous cases.”).

(1) Alice Step One

The Court stated that the critical question at Alice Step One for this case is whether the correct characterization of what the claims are directed to is either an abstract idea or a specific improvement in computer verification and authentication techniques.

Interestingly however, the Court stated that it needs not answer this question because even if the Court accepts the district court’s narrow characterization of the ’903 patent claims, the claims satisfy Alice step two.

The Court noted in footnote 3 that this very approach was followed in Amdocs (Israel) Ltd. v. Openet Telecom, Inc., 841 F.3d 1288, 1303 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (explaining that “even if [the claim] were directed to an abstract idea under step one, the claim is eligible under step two”).

(2) Alice Step Two

The district court recognized that the specification indicates that the “difference between [the] prior art methods and the claimed invention is that the [’]903 patent’s method ‘can be carried out with mobile devices of low complexity’ so that ‘all that has to be required from the authentication device function is to detect whether or not this function is active’” and that “the only activity that is required from the user for authentication purposes is to activate the authentication function at a suitable timing for the transaction.” But the district court cited column 1, lines 15–53 of the specification as purportedly admitting that detection of activation of an authentication function’s activity and the activation by users of an authentication function within a pre-determined time relation were “well-understood and routine, conventional activities previously known in the authentication technology field” (emphasis added).

The Court criticized the district court’s reliance on column 1, lines 15–53 as misplaced. The Court stated that, while column 1, lines 30–46 describes three prior art references, none teach the recited claim steps, and read in context, the rest of the passage cited by the district court makes clear that the claimed steps were developed by the inventors, are not admitted prior art, and yield certain advantages over the described prior art (emphasis added).

Duo also argued that using a second communication channel in a timing mechanism and an authentication function that is normally inactive, activated only preliminarily, and automatically deactivated is itself an abstract idea and thus cannot contribute to an inventive concept, and far from concrete (emphasis added). The Court disagreed, stating that the claim limitations are more specific and recite an improved method for overcoming hacking by ensuring that the authentication function is normally inactive, activating only for a transaction, communicating the activation within a certain time window, and thereafter ensuring that the authentication function is automatically deactivated (emphasis added). Referring to the Court’s recognition in Ancora Techs., Inc. v. HTC Am., Inc., 908 F.3d 1343 (Fed. Cir. 2018) that improving computer or network security can constitute “a non-abstract computer-functionality improvement if done by a specific technique that departs from earlier approaches to solve a specific computer problem,” the Court emphasized that, as the specification itself makes clear, the claims recite an inventive concept by requiring a specific set of ordered steps that go beyond the abstract idea identified by the district court and improve upon the prior art by providing a simple method that yields higher security (emphasis added).

II. Concurring Opinion

Judge Reyna’s concurrence challenged the Court’s approach of accepting the district court’s analysis under Alice step one and resolving the case under Alice step two. Judge Reyna argues that Alice Step two comes into play only when a claim has been found to be directed to patent-ineligible subject matter. He concluded that, employing step one, the claims at issue are directed to patent-eligible subject matter because, as the Court opinion stated, “[t]he ’903 Patent claims and specification recite a specific improvement to authentication that increases security, prevents unauthorized access by a third party, is easily implemented, and can advantageously be carried out with mobile devices of low complexity,” which is a step-one rationale.

Takeaway

· In the Alice inquiry, courts may assume that the claim in question does not pass Alice Step One without detailed analysis, and immediately move on to Alice Step Two.

· At both Alice Steps One and Two, the Court almost always inquires about improvements, i.e., the claimed advance over the prior art (“Under Alice step one, we consider “what the patent asserts to be the ‘focus of the claimed advance over the prior art.’”; “Turning then to Alice step two, we “consider the elements of each claim both individually and ‘as an ordered combination’ to determine whether the additional elements ‘transform the nature of the claim’ into a patent-eligible ap- plication.” … In computer-implemented inventions, the computer must perform more than “well-understood, routine, conventional activities previously known to the industry.””) (emphasis added). This approach may appear different from the views of the Supreme Court and the USPTO. See Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 132 S.Ct. 1289, 1304 (2012) (“We recognize that, in evaluating the significance of additional steps, the § 101 patent-eligibility inquiry and, say, the § 102 novelty inquiry might sometimes overlap. But that need not always be so.””); MPEP 2106.04(d)(1) (“[T]he improvement analysis at Step 2A [(Alice Step One)] Prong Two differs in some respects from the improvements analysis at Step 2B [(Alice Step Two)]. Specifically, the “improvements” analysis in Step 2A determines whether the claim pertains to an improvement to the functioning of a computer or to another technology without reference to what is well-understood, routine, conventional activity.”) (emphasis added).

CLAIMS SHOULD PROVIDE SUFFICIENT SPECIFICITY TO IMPROVE THE UNDERLYING TECHNOLOGY

| September 30, 2021

Universal Secure Registry LLC, v. Apple Inc., Visa Inc., Visa U.S.A. Inc.

Before TARANTO, WALLACH, and STOLL, Circuit Judges. STOLL

Summary

The Federal Circuit upheld a decision that all claims of the asserted patents are directed to an abstract idea and that the claims contain no additional elements that transform them into a patent-eligible application of the abstract idea.

Background

USR sued Apple for allegedly infringing U.S. Patent Nos. 8,856,539; 8,577,813; 9,100,826; and 9,530,137 that are directed to secure payment technology for electronic payment transactions. The four patents involve different authentication technology to allow customers to make credit card transactions “without a magnetic-stripe reader and with a high degree of security.”

The magistrate judge determined that all the representative claims were not directed to an abstract idea. Particularly it was concluded that the claimed invention provided a more secure authentication system. The magistrate judge also explained that the non-abstract idea determination is based on that “the plain focus of the claims is on an improvement to computer functionality itself, not on economic or other tasks for which a computer is used in its ordinary capacity.” However, the district court judge disagreed and concluded that the asserted claims failed at both Alice steps and the claimed invention was directed to the abstract idea of “the secure verification of a person’s identity.” The district court explained that the patents did not disclose an inventive concept—including an improvement in computer functionality—that transformed the abstract idea into a patent-eligible application.

The Federal Circuit concluded that the asserted patents claim unpatentable subject matter and thus upheld the district court’s decision.

Discussion

The Federal Circuit addressed all asserted patents. The claims in the four patents have fared similarly. The discussion here is focused on the ‘137 patent. The ’137 patent is a continuation of the ’826 patent and discloses a system for authenticating the identities of users. Claim 12 is representative of the ’137 patent claims at issue, reciting

12. A system for authenticating a user for enabling a transaction, the system comprising:

a first device including:

a biometric sensor configured to capture a first biometric information of the user;

a first processor programmed to: 1) authenticate a user of the first device based on secret information, 2) retrieve or receive first biometric information of the user of the first device, 3) authenticate the user of the first device based on the first biometric, and 4) generate one or more signals including first authentication information, an indicator of biometric authentication of the user of the first device, and a time varying value; and

a first wireless transceiver coupled to the first processor and programmed to wirelessly transmit the one or more signals to a second device for processing;

wherein generating the one or more signals occurs responsive to valid authentication of the first biometric information; and

wherein the first processor is further programmed to receive an enablement signal indicating an approved transaction from the second device, wherein the enablement signal is provided from the second device based on acceptance of the indicator of biometric authentication and use of the first authentication information and use of second authentication information to enable the transaction.

Claim 12 recites a system for authenticating the identities of users, including a first device. The first device can include a biometric sensor, a first processor, and a first wireless transceiver, where the device utilizes authentication of a user’s identity to enable a transaction.

The district court emphasized that the claims recite, and the specification discloses, generic well-known components—“a device, a biometric sensor, a processor, and a transceiver—performing routine functions—retrieving, receiving, sending, authenticating—in a customary order.”

The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court and found that the claims of ‘137 patent include some limitations but still are not sufficiently specific. The Federal Circuit cited their previous decision, Solutran, Inc. v. Elavon, Inc (Fed. Cir. 2019) that held claims abstract “where the claims simply recite conventional actions in a generic way” without purporting to improve the underlying technology. The Court explained that claim 12 does not tell a person of ordinary skill what comprises the secret information, first authentication information, and second authentication information.

USR cited Finjan, Inc. v. Blue Coat Systems, Inc (Fed. Cir. 2018), arguing that the claim is akin to the claim in Finjan whose claims are directed to a method of providing computer security by scanning a downloadable file and attaching the scanned results to the downloadable file in the form of a “security profile.” However, the Court differentiated Finjan, explaining that Finjan employed a new kind of file enabling a computer system to do things it could not do before, namely “behavior-based” virus scans. In contrast, the claimed invention combines conventional authentication techniques to achieve an expected cumulative higher degree of authentication integrity. The claimed idea of using three or more conventional authentication techniques to achieve a higher degree of security is abstract without some unexpected result or improvement. The Court also acknowledged that some of the dependent claims provide more specificity on these aspects, but still concluded the claimed is still merely conventional and the specification discloses that each authentication technique is conventional.

The district court also turned to Alice step two to determine that claim 12 “lacks the inventive concept necessary to convert the claimed system into patentable subject matter.” USR asserted that the use of a time-varying value, a biometric authentication indicator, and authentication information that can be sent from the first device to the second device form an inventive concept. The Federal Circuit rejected this argument, explaining that the specification makes clear that each of these devices and functions is conventional because the patent acknowledged that the step of generating time-varying codes for authentication of a user is conventional and long-standing. USR further argued that authenticating a user at two locations constitutes an inventive concept because it is locating the authentication functionality at a specific, unconventional location within the network. However, the Court found that the specification of the patent suggests that the claims only recite a conventional location for the authentication functionality and thus rejected the argument. The court further stated that there is nothing in the specification suggesting, or any other factual basis for a plausible inference (as needed to avoid dismissal), that the combination of these conventional authentication techniques results in an unexpected improvement beyond the expected sum of the security benefits of each individual authentication technique.

The Federal Circuit ruled that all the patents simply described well-known and conventional ways to perform authentication and did not include any technological improvements that transformed those abstract ideas into patent-eligible inventions. The Court also cited several of its previous decisions related to patent invalidity under Alice, noting that “patent eligibility often turns on whether the claims provide sufficient specificity to constitute an improvement to computer functionality itself.”

Takeaway

- An abstract idea is not patentable if it does not provide an inventive solution to a problem in implementing the idea.

- Claims may be abstract even when they are directed to physical devices but include generic well-known components that perform conventional actions in a generic way without improving the underlying technology or only to achieve an expected cumulative improvement.

Anything Under §101 Can be Patent Ineligible Subject Matter

| August 16, 2021

Yanbin Yu, Zhongxuan Zhang v. Apple Inc., Fed. Cir. 2020-1760Yanbin Yu, Zhongxuan Zhang v. Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd., Samsung Electronics America, Inc., Fed. Cir. 2020-1803

Decided on June 11, 2021

Before Newman, Prost, and Taranto (Opinion by Prost, Dissenting opinion by Newman)

Summary

Yu had ’289 patent which is titled “Digital Cameras Using Multiple Sensors with Multiple Lenses” and sued Apple and Samsung at District Court for infringement. The District Court found that the ’289 patent is directed towards an abstract idea and does not include an inventive concept. The District Court held the patent was invalid under §101 and granted the defendant’s motion to dismiss. Yu appealed to the CAFC. The majority panel affirmed the District Court’s decision. However, Judge Newman dissented and wrote that the disputed patent is directed towards a mechanical and electronic device and not an abstract idea. The Judge also pointed out that neither the majority panel nor the District Court decided patentability under §102 or 103.

Details

Background

According to Yu, early digital camera technologies were starting to flourish in the 1990s. However, before the ’289 patent, “the technological limitations of then-existing image sensors—used as the capture mechanism—caused digital cameras to produce lower quality images compared with those produced by traditional film cameras.” The’289 patent was applied in 1999 and issued in 2003. Yu believed that “the ’289 patent solved the technological problems associated with prior digital cameras by providing an improved digital camera having multiple image sensors and multiple lenses.[1]” Yu also explained that “all dual-lens cameras on the market today use the techniques claimed in the ’289 Patent[2]” and therefore, sued Apple and Samsung (“the Defendants”) for infringement of claims 1, 2, and 4 of the ’289 patent in October 2018 (before the ’289 patent expires in 2019). In response, the Defendants filed a Rule 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss, asserting that the claims are directed towards an abstract idea under §101.

Claim 1 of the ’289 patent

1. An improved digital camera comprising:

a first and a second image sensor closely positioned with respect to a common plane, said second image sensor sensitive to a full region of visible color spectrum;

two lenses, each being mounted in front of one of said two image sensors;

said first image sensor producing a first image and said second image sensor producing a second image;

an analog-to-digital converting circuitry coupled to said first and said second image sensor and digitizing said first and said second intensity images to produce correspondingly a first digital image and a second digital image;

an image memory, coupled to said analog-to-digital converting circuitry, for storing said first digital image and said second digital image; and

a digital image processor, coupled to said image memory and receiving said first digital image and said second digital image, producing a resultant digital image from said first digital image enhanced with said second digital image.

The District Court held that the ’289 patent was directed to “the abstract idea of taking two pictures and using those pictures to enhance each other in some way” and “the asserted claims lack an inventive concept, noting “the complete absence of any facts showing that the claimed elements were not well-known, routine, and conventional.” Therefore, the District Court concluded that the ’289 patent was directed to an ineligible subject matter and entered judgment for Defendants. Yu appealed to the CAFC.

Majority Opinion

At the CAFC, as we have seen in the various other §101 precedents, the panel applied the two-step Mayo/Alice framework.

Step 1: “Whether a patent claim is directed to an unpatentable law of nature, natural phenomenon, or abstract idea. Alice, 573 U.S. at 217.”

Step 2: If Step 1 is Yes, “Whether the claim nonetheless includes an “inventive concept” sufficient to “‘transform the nature of the claim’ into a patent-eligible application. Id.”

(If Step 2’s answer is No, the invention is not a patent-eligible subject matter.)

In the majority opinion filed by Judge Prost, as to Step 1, the court applied the approach to the Step 1 inquiry “by asking what the patent asserts to be the focus of the claimed advance over the prior art” and concluded that “claim 1 is “directed to a result or effect that itself is the abstract idea and merely invoke[s] generic processes and machinery” rather than “a specific means or method that improves the relevant technology.” The majority opinion also mentioned that “Yu does not dispute that, as the district court observed, the idea and practice of using multiple pictures to enhance each other has been known by photographers for over a century.” The majority opinion also noted that although, “Yu’s claimed invention is couched as an improved machine (an “improved digital camera”), … “whether a device is “a tangible system (in § 101 terms, a ‘machine’)” is not dispositive”. Thus, the majority panel concluded that “the focus of claim 1 is the abstract idea.”

As to Step 2, the majority opinion concludes that claim 1 does not include an inventive concept sufficient to transform the claimed abstract idea into a patent-eligible invention because “claim 1 is recited at a high level of generality and merely invokes well-understood, routine, conventional components to apply the abstract idea” discussed in Step 1. Yu raised the prosecution history to prove that “the ’289 patent were allowed over multiple prior art references.” Also, Yu argued that the claimed limitations are “unconventional” because “the claimed “hardware configuration is vital to performing the claimed image enhancement.” However, the court was not convinced with this argument and conclude that “the claimedhardware configuration itself is not an advance and does not itself produce the asserted advance of enhancement of one image by another, which, as explained, is an abstract idea.”

Thus, the majority of the court concluded that the ‘’289 patent is not patent-eligible subject matter under §101. Therefore, the court hold for the Defendants.

Dissenting Opinion

In the dissenting opinion, Judge Newman said that “this camera is a mechanical and electronic device of defined structure and mechanism; it is not an “abstract idea” and “a statement of purpose or advantage does not convert a device into an abstract idea.”

The judge explained that “claim 1 is not for the general idea of enhancing camera image”, but “for a digital camera having a designated structure and mechanism that perform specified functions.” The Judge further mentioned, “the ‘abstract idea’ concept with respect to patent-eligibility is founded in the distinction between general principle and specific application.” The Judge quoted Diamond v. Chakrabarty and emphasized that “Congress intended statutory subject matter to ‘include anything under the sun that is made by man.’”

Judge Newman noted that “the ’289 patent may or may not ultimately satisfy all the substantive requirements of patentability”, and noted that neither the majority opinion and the district court discussed §102 and §103.

Takeaway

- After 7 years from Alice, we are still witnessing the profound impact that Alice has on §101 jurisprudence, and waiting for further judicial, legislative, and/or administrative clarity.

- In a previous §101 decision in American Axel (previously reported by John P. Kong), the dissenting opinion by Judges Chen and Wallach criticized that §101 swallowed §112. Now, Judge Newman criticized that §101 swallowed §102 and §103. The dire warning by the Supreme Court about §101 swallowing all of patent law seems to have come full circle.

- Judge Newman’s criticism of §101 swallowing §102 and §103 can be an added argument for appeal for another case and may help get these issues before the Supreme Court.

- John P. Kong said that The approach for determining the Step 1 inquiry, i.e., “by asking what the patent asserts to be the focus of the claimed advance over the prior art” is the source of much of the court’s criticisms. This approach was never vetted, and it conflates §101 with §102 and §103 issues. First, this “focus” is just another name for deriving the “point of novelty,” “gist,” “heart,” or “thrust” of the invention, which had previously been discredited by Supreme Court and Federal Circuit decisions relating to §102 and §103 issues. The problem with tests such as these is that it subtracts out various “conventional” features of the claimed invention (like what is done for the “claimed advance over the prior art”), and thus violates the Supreme Court requirement to consider the claim “as a whole.” If the point of novelty, gist, or heart of the invention contravenes the requirement to consider the claim “as a whole” in the §102 and §103 contexts, then it should likewise contravene the same Supreme Court requirement to consider the claim “as a whole” in the §101 context (as noted in John P. Kong’ “Today’s Problems with §101 and the Latest Federal Circuit Spin in American Axle v. Neapco” powerpoint, Dec. 2020). Judge Newman’s dissent echoes the same.

- John P. Kong also said that Enfish moved up into Step 1 the “improvement in technology” comment in Alice regarding the inventive concept consideration under Step 2 because some computer technology isn’t inherently abstract and thus should not be automatically subject to Alice’s Step 2 and its inventive-concept test. Enfish only had a passing reference to “inquiring into the focus of the claimed advance over the prior art” citing Genetic Techs v. Merial (Fed. Cir. 2016), as support for considering the “improvement in technology” in Alice Step 1. Herein lies the problem. The “improvement in technology” concept pertains to whether the claims are directed to a practical application, instead of an abstract idea. The “claimed advance over prior art” is not a substitute for, and not the same as, determining whether there is a practical application reflected in an improvement in technology. Stated differently, there can still be a practical application (and therefore not an abstract idea) even without checking the prior art and subtracting out “conventional” elements from the claim to discern a “claimed advance over the prior art.” While a positive answer to the “claimed advance over the prior art” would satisfy the “improvement in technology” point as being a practical application justifying eligibility, a negative answer to the “claimed advance over the prior art” does not diminish the claim being directed to a practical application (such as for an electric vehicle charging system, a garage door opener, a manufacturing method for a car’s driveshaft, or for a camera). But, in Electric Power Group v Alstom (Fed. Cir. 2016), the Fed. Cir. considered whether the “advance” is an abstract idea using a computer as a tool or a technological improvement in the computer or computer functionality (in an “improvement in technology” inquiry). And then, in Affinity Labs of Texas LLC v. DirecTV LLC, the Fed Cir cemented the “claimed advance” spin into Step 1, subtracting out “general components such as a cellular telephone, a graphical user interface, and a downloadable application” to arrive at a purely functional remainder that constituted an abstract idea of out-of-region delivery of broadcast content, without offering any technological means of effecting that concept (the 1-2 knockout of: subtract generic elements, and no “how-to” for the remainder). This laid the groundwork for §101 swallowing §§112, 102 and 103.

[1] See Brief, USDC ND of Ca Appeal Nos. 20-1760, -1803.

[2] See Yu v. Apple, United States District Court for the Northern District of California in No. 3:18-cv-06181-JD

Tailored Advertising Claims Are Invalidated Due to Lack of Improvements to Computer Functionality

| June 8, 2021

Free Stream Media Corp., DBA Samba Tv, V. Alphonso Inc., Ashish Chordia, Lampros Kalampoukas, Raghu Kodige

Decided on May 11, 2021

Before DYK, REYNA, and HUGHES. Opinion by REYNA.

Summary

The Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s decision and found that the asserted claims directed to tailored advertising were patent ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

Background