If It Isn’t The Same, It’s Different!

Adele Critchley | December 4, 2025

MERCK SERONO S.A., Appellant v. HOPEWELL PHARMA VENTURES, INC., (Presidential)

Date of Decision: October 30, 2025

Panel: Before HUGHES, LINN, and CUNNINGHAM, Circuit Judges. LINN, Circuit Judge.

Summary:

Merck Serono S.A. (“Merck”) appeals the determinations by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) in two consolidated inter partes reviews (“IPR”). In this case, the Board held several claims of Merck’s U.S. Patent No. 7,713,947 (“’947 patent”) and U.S. Patent No. 8,377,903 (“’903 patent”) unpatentable as obvious over a combination of Bodor and Stelmasiak. The Patents in question related to oral formulations of cladribine to treat MS.

In 2002, Serono partnered with IVAX Corporation (“Ivax”) to develop oral cladribine to treat MS. Serono was acquired by Merck in 2006. Under their joint research agreement, Merck would “‘conduct clinical trials’ to determine ‘the dose, safety, and/or efficacy’” of cladribine oral tablets, and Ivax would “develop an oral dosage formulation of [cladribine] in tablet or capsule form suitable for use in clinical trials and commercial sale.” On March 26, 2004, Ivax employees Drs. Bodor and Dandiker filed the Bodor international patent application (the primary reference used by Hopewell here). The application was published less than one year before the effective filing date of the patents in-suit, which were each filed December 22, 2004. Both patents list as inventors: Drs. De Luca, Ythier, Munafo, and Lopez Bresnahan (collectively, “named inventors”). All four were employees of Serono and, in at least some way, were a part of the development team that developed the claimed oral cladribine regimen back in 2002 (as evidenced by meeting minutes).

Hopewell Pharma Ventures, Inc. (“Hopewell”) filed two IPRs, respectively challenging claims of the ’947 patent and the ’903 patent as obvious over Bodor and Stelmasiak. The Board held that all challenged claims were unpatentable as obvious thereover. In doing so, the Board rejected patentee’s legal argument that “a reference’s disclosure of the invention of a subset of inventors is disqualified as prior art against the invention of all the inventors.” Id. at 36 (emphasis in original). The rule of In re Land, 368 F.2d 866 (CCPA 1966), that any difference in the “inventive entity” between the reference disclosure and the challenged claims—whether adding or subtracting inventors—rendered the reference a disclosure “by another” and therefore available as prior art, was affirmed. The Board also found there was insufficient corroboration evidence that De Luca’s contribution provided an inventive contribution found in Bodor, as would be required to exclude the disclosure from the prior ar.

Ultimately the CAFC affirmed the Board’s determinations.

Under pre-AIA § 102(e), a patent is anticipated if “the invention was described in . . . a patent granted on an application for patent by another filed in the United States before the invention by the applicant for patent.” 35 U.S.C. 102(e) (emphasis added).

The question presented to the CAFC in this appeal is “whether and to what extent a disclosure invented by fewer than all the named inventors of a patent may be deemed a disclosure “by another” and thus included in the prior art, or whether the disclosure should properly be treated as “one’s own work” and therefore excluded from the prior art.”

Merck argued for the latter, but the CAFC found for the first.

Merck focuses on the following two sentences in Applied Materials, Inc. v. Gemini Res. Corp., 835 F.2d 279 (Fed. Cir. 1987):

However, the fact that an application has named a different inventive entity than a patent does not necessarily make that patent prior art.

Id. at 281 (citing In re Kaplan, 789 F.2d 1574, 1576 (Fed. Cir. 1986)); Appellant’s Opening Br. 30–31. And:

Even though an application and a patent have been conceived by different inventive entities, if they share one or more persons as joint inventors, the 35 U.S.C. § 102(e) exclusion for a patent granted to ‘another’ is not necessarily satisfied.

Applied Materials, 835 F.2d at 281 (emphasis added); Appellant’s Opening Br. 29.

Merck essentially argued that the Courts have rejected a bright-line rule requiring an identical inventive entity to exclude a reference as not “by another.”

The CAFC held that Merck overreads Applied Materials. The CAFC clarified that the decision did not rely on the fact that two of the three named inventors in the later patent were named in the earlier reference patent. Instead, the decision rested on the fact that the later patent and the earlier reference patent were descendants of the same application. The CAFC emphasized that it is erroneous to place too much reliance on the inventive entity “named” in the earlier reference patent: “[T]he fact that an application has named a different inventive entity than a patent does not necessarily make that patent prior art.” Id. (emphasis added). Instead, like in Land, the key question is whether the disclosure in the earlier reference evidenced knowledge by “another” before the patented invention.

The CAFC stated that:

Our case law—in particular, Land—precludes our adoption of the policy argument presented by Merck. As those cases make clear, for a reference not to be “by another,” and thus unavailable as prior art under pre-AIA § 102(e), the disclosure in the reference must reflect the work of the inventor of the patent in question. That is clear enough when a single inventor is involved. What should also be clear is that when the patented invention is the result of the work of joint inventors, the portions of the reference disclosure relied upon must reflect the collective work of the same inventive entity identified in the patent to be excluded as prior art. That showing may be made by fewer than all the inventors but nonetheless must evince the joint work of them all to avoid being considered a work “by another” under the statute. Any incongruity in the inventive entity between the inventors of a prior reference and the inventors of a patent claim renders the prior disclosure “by another,” regardless of whether inventors are subtracted from or added to the patent.

Here, ultimately, Merck failed to provide sufficient evidence that one of the inventors had made an inventive contribution to the relevant disclosure in Bodor, but even if Merck had shown such a contribution, the evidence did show that Bodor’s inventors had made significant contributions, so the reference would still qualify as “by another”.

Next, Merck next argued that it was “surprised by the Board’s application of the above-discussed rule requiring complete identity of inventive entity because the rule is contrary to several provisions of the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (“MPEP”).”

Merck relies on the following MPEP sections. Appellant’s Opening Br. 34. MPEP § 2132.01:

An inventor’s or at least one joint inventor’s disclosure of his or her own work within the year before the application filing date cannot be used against the application as prior art.

And MPEP § 2136.05(b):

[E]ven if an inventor’s or at least one joint inventor’s work was publicly disclosed prior to the patent application, the inventor’s or at least one joint inventor’s own work may not be used against the application subject to preAIA 35 U.S.C. 102 unless there is a time bar.

Hopewell responded that Merck “did not lack notice of the rule because the MPEP expressly adopts the rule of Land in § 2136.04 (titled “Different Inventive Entity; Meaning of ‘By Another’”)”.

The CAFC agreed with Hopewell. Moreover, the CAFC noted that “To the extent the MPEP describes our case law differently, that interpretation does not control,” but nonetheless failed to agree that the MPEP was different.

Accordingly, the CAFC found that Bodor was proper prior art. Once confirmed, the Court went on to affirm the Board’s determination that the challenged claims were obvious in view of Bodor and Stelmasiak,

Comments:

- The phrase “by another” requires complete identity of the inventive entity to exclude a reference as prior art. In order to disqualify overlapping inventor references, corroborated evidence must be provided that all named inventors contributed to the inventive aspect of prior relevant disclosure. Thus, it is important for inventors working under joint research agreements to keep up-to-date lab and meeting notes that could aid in establishing such corroborated evidence.

- MPEP is not controlling over case law where interpretation is distinct.

when an apparatus claim depends on functioning claim to describe the apparatus, what the device does and how it does it are highly relevant to understanding what the device is

Sung-Hoon Kim | October 22, 2025

ROTHSCHILD CONNECTED DEVICES INNOVATIONS, LLC v. COCA-COLA COMPANY

Date of Decision: October 21, 2025

Before: Prost (author), Lourie, and Stoll

Summary:

The CAFC agreed with the decision of the district court and affirmed the summary judgement of noninfringement because by looking at the claim language and the specification, the claimed communication module must be configured to perform its steps in the order in which they are written, thereby allowing a narrow claim construction.

Details:

Rothschild Connected Devices Innovations, LLC (“Rothschild”) owns U.S. Patent No. 8,417,377 (“the ’377 patent) and sued Coca-Cola Co. (“Coca-Cola”) for infringing the ’377 patent in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia, which granted summary judgement of noninfringement.

At issue is an independent claim 11, which reads as follows:

A beverage dispenser comprising:

at least one compartment containing an element of a beverage;

at least one valve coupling the at least one compartment to a dispensing section configured to dispense the beverage;

a mixing chamber for mixing the beverage;

a user interface module configured to receive an[] identity of a user and an identifier of the beverage;

a communication module configured to transmit the identity of the user and the identifier of the beverage to a server over a network, receive user generated beverage product preferences based on the identity of the user and the identifier of the beverage from the server and communicat[e] the user generated beverage product preferences to controller; and

the controller coupled to the communication module and configured to actuate the at least one valve to control an amount of the element to be dispensed and to actuate the mixing chamber based on the user gene[r]ated beverage product preferences.

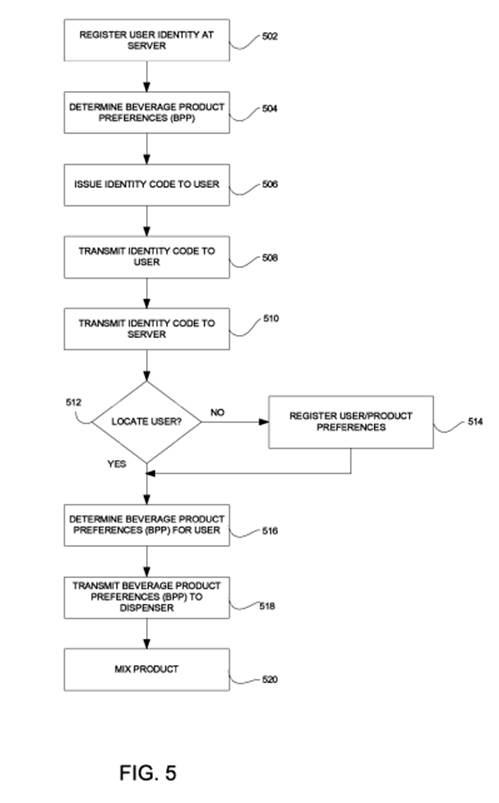

At issue in this appeal is whether the claimed communication module must be configured to perform its steps in the order in which they are written:

(1) “transmit the identity of the user and the identifier of the beverage to a server over a network”;

(2) “receive user generated beverage product preferences based on the identity of the user and the identifier of the beverage from the server”; and

(3) “communicat[e] the user generated beverage product preferences to controller.”

The district court held that the communication module must be configured to perform these steps in that particular order.

The CAFC agreed with the decision of the district court and affirmed the summary judgement of noninfringement.

The CAFC applied a two-part test for determining if steps that do not otherwise recite an order “must nonetheless be performed in the order in which they are written.”

First, the CAFC look at the claim language to determine if, as a matter of logic or grammar, they must be performed in the order written.

Second, if not, the CAFC review the specification to determine whether it directly or implicitly requires such construction.

If not, the sequence in which such steps are written is not a requirement.

In this case, the CAFC held that as a matter of logic or grammar, the communication module must be configured to perform its steps in the order in which they are written – to a server and from the server.

In particular, the CAFC noted that the use of “based on” indicates that the first step precedes the second step.

Furthermore, the CAFC noted that the specification clearly contains language and figures (the below Fig. 5) describing this order and does not contain any suggestion as to Rothschild’s contrary claim interpretation.

Rothschild argued that independent claim 11 is an apparatus claim, and therefore the claim does not require ordered steps (this apparatus claim covers what a device is, not what a device does).

The CAFC noted that while apparatus claims focus on the structure instead of the operation or use, when an apparatus claim depends on functioning claim to describe the apparatus, what the device does and how it does it are “highly relevant to understanding what the device is.”

Accordingly, the CAFC affirmed the summary judgement of noninfringement.

Takeaway:

- Functional claim language matters even for apparatus claims. When an apparatus claim depends on functioning claim to describe the apparatus, what the device does and how it does it are relevant to understanding what the device is.

- In order to obtain broad coverage of functional claim language, the specification should include several embodiments and figures describing broad functional coverage.

Functional Limitation, Claim Construction, and Obviousness: Bayer v. Mylan

Bo Xiao | September 24, 2025

BAYER PHARMA AKTIENGESELLSCHAFT, v. MYLAN PHARMACEUTICALS INC., TEVA PHARMACEUTICALS USA, INC., INVAGEN PHARMACEUTICALS INC.

Date of Decision: September 23, 2025

Before: MOORE, Chief Judge, CUNNINGHAM, Circuit Judge, and SCARSI, District Judge.

Summary

The Federal Circuit affirmed in part, vacated in part, and remanded the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s decision invalidating claims of Bayer Pharma AG’s patent. The court upheld the invalidation of claims 1-4 but vacated and remanded with respect to claims 5-8.

Background

Bayer owns the ’310 patent (U.S. Patent No. 10,828,310), which claims methods for reducing the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and/or peripheral artery disease (PAD) through administration of rivaroxaban and aspirin.

Independent claim 1 recites administration of rivaroxaban and aspirin in clinically proven amounts. Independent claim 5 recites once-daily administration of a first product comprising rivaroxaban and aspirin and a second product comprising rivaroxaban. Claims 1 and 5 are listed below with emphasis added:

1. A method of reducing the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke or cardiovascular death in a human patient with coronary artery disease and/or peripheral artery disease, comprising administering to the human patient rivaroxaban and aspirin in amounts that are clinically proven effective in reducing the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke or cardiovascular death in a human patient with coronary artery disease and/or peripheral arterial dis-ease, wherein rivaroxaban is administered in an amount of 2.5 mg twice daily and aspirin is administered in an amount of 75-100 mg daily.

5. A method of reducing the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke or cardiovascular death in a human patient with coronary artery disease and/or peripheral artery disease, the method comprising administering to the human patient rivaroxaban and aspirin in amounts that are clinically proven effective in reducing the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke or cardiovascular death in a human patient with coronary artery disease and/or peripheral arterial disease, wherein the method comprises once daily administration of a first product comprising rivaroxaban and aspirin and a second product comprising rivaroxaban, and further wherein the first product comprises 2.5 mg rivaroxaban and 75-100 mg aspirin and the second product comprises 2.5 mg rivaroxaban.

Mylan, Teva, and InvaGen filed substantively identical IPR petitions, arguing that a 2016 journal article by Foley (summarizing a trial which includes its dosing regimen of 2.5 mg rivaroxaban twice daily and 100 mg aspirin once daily without disclosing the trial results) and a 2014 journal article by Plosker (disclosing a dosing regimen of 2.5 mg rivaroxaban twice daily, co-administered with 75-100 mg aspirin) anticipated or rendered the claims obvious. The Board agreed and held all challenged claims unpatentable. Bayer appealed.

Discussion

The Federal Circuit addressed four disputes.

The first dispute is related to the phrase “clinically proven effective.” The Board had treated it as non-limiting or inherently anticipated. Bayer argued that the phrase should operate as a substantive limitation on the claims. According to Bayer, the language required that the claimed dosages of rivaroxaban and aspirin be supported by actual clinical trial evidence of efficacy, which in turn distinguished the claims from prior art references such as Foley. Bayer emphasized that Foley disclosed dosing regimens but did not provide trial results demonstrating that the regimens were effective and therefore could not anticipate or render the claimed methods obvious.

The Federal Circuit rejected this position, explaining that it did not decide whether the phrase “clinically proven effective” was a limiting element in claims 1-8. Even assuming it was limiting, the court reasoned that the phrase would not affect patentability because it merely described a characteristic of the treatment regimen rather than altering the steps of the claimed method. The court emphasized that the claims already specify the exact dosages of rivaroxaban and aspirin to be administered, and those dosages remain unchanged regardless of whether clinical trials later demonstrate efficacy. Accordingly, the limitation was deemed functionally unrelated to the claimed method and insufficient to distinguish the claims from the prior art.

The second dispute concerned the proper construction of the phrase “first product comprising rivaroxaban and aspirin” in claim 5. The Board had construed this language broadly to encompass circumstances where rivaroxaban and aspirin were provided in separate dosage forms and administered together, not limited to a single dosage form, and, if administered separately, the dosage forms could be administered simultaneously or sequentially.

The Federal Circuit disagreed with that interpretation. Relying on both the plain language of the claim and the description in the specification, the court concluded that “a first product comprising rivaroxaban and aspirin” required a single dosage form containing both ingredients. The court emphasized that the specification describes that “combination therapy may be administered using separate dosage forms for rivaroxaban and aspirin, or using a combination dosage form containing both rivaroxaban and aspirin.” The court agreed with Bayer that “first product comprising rivaroxaban and aspirin” corresponds to the latter, which narrows the term.

Therefore, the Federal Circuit remanded for further consideration so that the Board’s analysis of the obviousness arguments would be under the correct construction of the “first product” term.

The third dispute concerned whether the Board adequately explained a skilled artisan’s motivation to combine the prior art references with a reasonable expectation of success. The Federal Circuit agreed with the Board’s decision and found it supported by substantial evidence. The court noted that the Board identified both an overlap in the disclosed dosage ranges and the established practice of administering aspirin within that range. The court further found that Foley and Plosker described similar motivations for combining rivaroxaban with aspirin in patients with cardiovascular risk, which supported the Board’s conclusion that a skilled artisan would have had reason to combine the references with a reasonable expectation of success. Accordingly, the Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s determination of obviousness as to dependent claims 3-4 and 6-7.

The fourth dispute concerned Bayer’s argument that its own clinical trial provided clinical proof of efficacy was an unexpected result. The Federal Circuit rejected this position, holding that there was no nexus between the asserted unexpected property and the claimed invention. The court explained that the asserted results were tied only to the “clinically proven effective” limitation, which it had already deemed functionally unrelated to the actual treatment method. Without that nexus, the secondary consideration of unexpected results could not support nonobviousness.

Takeaways

- Claim language that merely recites a property or result, without further defining the claimed steps or structure, may be deemed functionally unrelated and insufficient to establish distinction over the prior art.

- Secondary considerations require a demonstrated nexus between the evidence presented and the claimed invention as construed.

The Federal Circuit’s First AIA Derivation Case

John Kong | September 10, 2025

Global Health Solutions LLC v. Selner

Date of Decision: August 26, 2025

Before: Stoll, Stark, Circuit Judges. Goldberg, District Judge.

Summary:

The Federal Circuit addressed a derivation proceeding under the AIA for the first time. While derivation issues arose in pre-AIA interference proceedings, AIA derivation does not require a showing of who is first-to-conceive. Independent conception by an accused inventor overcomes the derivation accusation.

Procedural History:

Global Health Solutions (GHS) petitioned for an AIA derivation proceeding against Selner. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) granted the petition because GHS identified at least one claim in GHS’ application that is (i) the same or substantially the same as Selner’s claimed invention and is also (ii) the same or substantially the same as the invention disclosed to Selner. After the derivation proceedings, the Board ruled in Selner’s favor. GHS appealed to the Federal Circuit.

Background:

In 2013, Selner and Burnam worked together, although unsuccessfully, to make and sell a novel emulsifier-free wound treatment ointment. Burnam later left and formed GHS. GHS and Selner each filed a patent application on a wound treatment ointment and method for making it, resulting in permanently suspended nanodroplets without the use of an emulsifier that can irritate a patient’s skin. Selner is the first-filer, and GHS is the second-filer. An AIA derivation proceeding provides a limited opportunity for a first-inventor second-filer to obtain a patent despite another person filing an application first (first-filer) in the situation where the first filer derived the invention from the second-filer. During the derivation proceedings, the Board found that Burnam conceived the invention and communicated it to Selner, but the Board also found that Selner proved conception earlier the same day Burnam contacted him.

Decision:

Pre-AIA case law involving derivation often arose in the context of an interference to determine who was the first to invent under the previous first-to-invent law. However, when the AIA eliminated interferences and transformed 35 USC 135 from a law governing interferences to one governing derivation proceedings, Congress did not specify what a second-filer inventor must prove to show that the first-filer inventor derived the claimed invention from the second-filer inventor. However, the court concludes that “the required elements of a derivation claim have not changed other than to the extent necessary to reflect the transition from a first-to-invent to a first-to-file system of patent administration.”

Derivation in an AIA case requires the petitioner to “produce evidence sufficient to show (i) conception of the claimed invention, and (ii) communication of the conceived invention to the respondent prior to respondent’s filing of that patent application.” In a footnote, the Court sidestepped any decision regarding whether a party’s burden of proof in an AIA derivation proceeding is by a preponderance of evidence or by clear and convincing evidence (in pre-AIA interferences, proof of derivation was by clear and convincing evidence) since neither party raised this issue. But, a “respondent can overcome the petitioner’s showing by proving independent conception prior to having received the relevant communication from the petitioner.”

In particular, Selner need not prove that he was the first-to-conceive. Although the Board erred in focusing on whether Selner or Burnam was the first-to-invent or first-to-conceive, that was harmless error. “[A] first-to-file respondent like Selner need only prove that his conception was independent.” While the Board erroneously reached its decisions predicated on Selner being the first-to-conceive, the Board, in doing so, also indirectly determined that Selner independently conceived, and therefore, did not derive his invention from Burnam.

GHS argued that the Board erred by not requiring Selner to corroborate his inventorship with evidence independent of himself. The court found no such error. First, a “rule of reason test is used to determine whether an alleged inventor’s testimony is sufficiently corroborated.” Second, “the Board must consider ‘all pertinent evidence’ and then determine whether the ‘inventor’s story’ is credible.” More importantly, “[d]ocumentary or physical evidence that is made contemporaneously with the inventive process provides the most reliable proof that the inventor’s testimony has been corroborated.” Here, the corroboration was achieved through emails retrieved by Selner’s attorney’s law clerk from Selner’s AOL email account that were generated contemporaneously with the inventive process. And, such emails, whose authenticity was not challenged by GHS, do not require independent corroboration. In addition, the metadata generated by the web-based email server is independent of Selner’s own testimony and documents. Accordingly, the Board had substantial evidence for its findings of fact and there was no reversible error.

GHS argued that Selner did not show reduction to practice to prove conception. The court agreed with the Board that conception can occur without reducing the invention to practice. “Selner’s conception was complete at the point at which he was ‘able to define [the Invention] by its method of preparation’ or when he had formed ‘a definite and permanent idea of the complete and operative invention.’”

GHS argued that Burnam should be named as a co-inventor on Selner’s application. The court refused because GHS did not properly present this request to the Board and is thus forfeited. 37 CFR 42.22 requires a contested request for correction of inventorship in a patent application to be made in a separate motion, including a “statement of the precise relief requested” and a “full statement of the reasons for the relief requested, including a detailed explanation of the significance of the evidence including material facts, and the governing law, rules, and precedent.” No such separate motion was made to the Board, nor was any detailed explanation supporting joint inventorship and material facts relating thereto provided.

Takeaways:

In this case, even though the second-filer showed conception and communication of the invention to the first-filer, the first-filer’s independent conception was a complete defense over the derivation accusation. Unfortunately for Burnam (because GHS did not file a separate motion for correcting inventorship in Selner’s application), the “independent” nature of Selner’s conception was never really challenged despite all the interactions between him and Selner.

This case also provided good reminders that reduction to practice is not required for showing conception, and that contemporaneously generated evidence can corroborate the inventor’s story.