A comparison of an accused product to a commercial product that meets all the claim limitations for finding infringement of the claim

| April 29, 2019

TEK Global S.R.L. v. Sealant Systems International Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2019) (Prost, C.J.) (Case No. 17-2507)

March 29, 2019

Prost, Chief Judge, Dyk and Wallach, Circuit Judges. Court opinion by Chief Judge Prost.

Summary

In a precedential opinion, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s claim construction in a specific context that an asserted claim including “container connecting conduit” was not subject to 35 U.S.C 112, ¶ 6 (112(f)) because the term “conduit” recites sufficiently definite structure to avoid classification as a nonce term. The Federal Circuit also affirmed the district court’s overruling of the accused infringer’s objections to certain alleged product-to-product comparisons in the patentee’s closing argument with general guidance that, despite the maxim that to infringe a patent claim, an accused product must meet all the limitations of the claim, a comparison of the accused product to a commercial product that meets all the claim limitations may support a finding of infringement of the claim.

Details

I. background

1. Patent in Dispute

TEK Corporation and TEK Global, S.R.L. (collectively, “TEK”) owns U.S. Patent No. 7,789,110 (“’110 patent”), directed to an emergency kit for repairing vehicle tires deflated by puncture.

In a lawsuit by TEK against Sealant Systems International and ITW Global Tire Repair (collectively, “SSI”) at the United States District Court for the Northern District of California (“district court”), claim 26 is the only asserted independent claim:

26. A kit for inflating and repairing inflatable articles; the kit comprising a compressor assembly, a container of sealing liquid, and conduits connecting the container to the compressor assembly and to an inflatable article for repair or inflation, said kit further comprising an outer casing housing said compressor assembly and defining a seat for the container of sealing liquid, said container being housed removably in said seat, and additionally comprising a container connecting conduit connecting said container to said compressor assembly, so that the container, when housed in said seat, is maintained functionally connected to said compressor assembly, said kit further comprising an additional hose cooperating with said inflatable article; and a three-way valve input connected to said compressor assembly, and output connected to said container and to said additional hose to direct a stream of compressed air selectively to said container or to said additional hose.

2. Preceding Proceedings

In claim construction proceedings, SSI argued that “conduits connecting the container” and “container connecting conduit” in claim 26 are subject to 35 U.S.C. 112, ¶ 6, and that the claim requires a fast-fit coupling, which the accused product lacks.

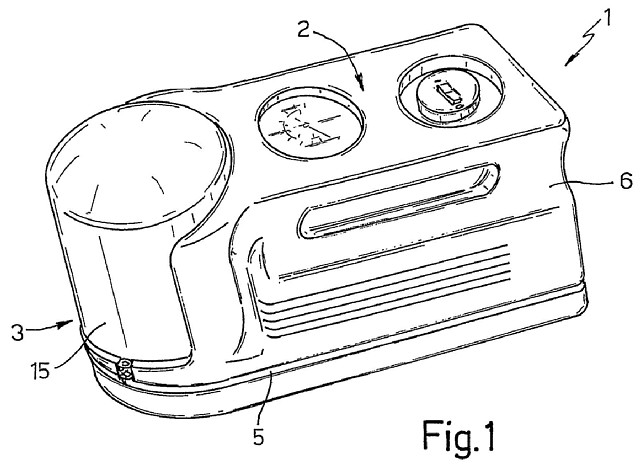

FIG. 1, showing a “view in perspective of a repair kit [1] comprising a container [3] of sealing liquid [and a compressor assembly 2],” is reproduced below

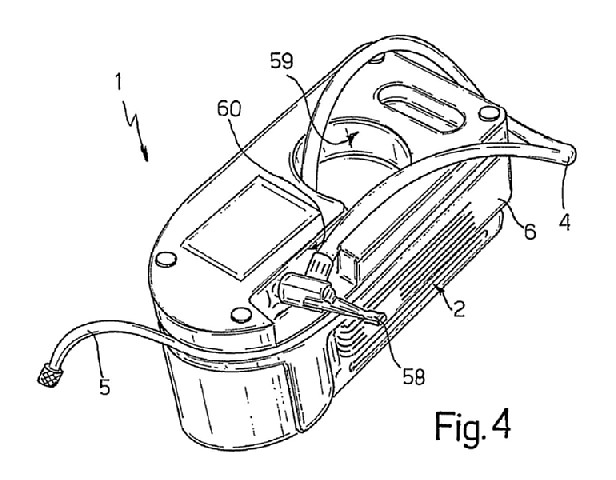

FIG. 4, showing a “underside view in perspective [o]f the FIG. 1 kit [1] partly disassembled,” and a portion of the specification of ’110 patent, relevant to the “fast-fit coupling” are reproduced below:

“Conveniently, hose 4 [i]s fitted on its free end with a fast-fit, e.g. lever-operated, coupling 58.” ’110 patent col. 4 ll. 7–9.

The magistrate judge rejected SSI’s contention, and entered an order respectively construing these terms (“conduits connecting the container” and “container connecting conduit”) as “hoses and associated fittings connecting the container to the compressor assembly and to an inflatable article for repair or inflation” and “a hose and associated fittings for connecting the container to the compressor assembly.”

Following the claim construction, SSI moved for summary judgment of invalidity, arguing that claim 26 was obvious over U.S. Patent Application No. 2003/0056851 (“Eriksen”) in view of Japanese Patent No. 2004-338158 (“Bridgestone”). The district court granted SSI’s motion with determinations that the term “additional hose cooperating with said inflatable article” did not require a direct connection between the additional hose and the inflatable article, and that Bridgestone discloses an air tube (54) that works together with a tire, even though it is not directly connected to the tire, and that air tube (54) therefore represents the element of an additional hose (83) cooperating with the tire. TEK appealed the district court’s order to the Federal Circuit.

The Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s construction of the “cooperating with” limitation and its subsequent invalidity determination, and remanded the case back to the district court, because SSI “has not had an opportunity to make a case for invalidity in light of this court’s claim construction.”

On remand, SSI again moved for summary judgment of invalidity, contending that “it would have been obvious . . . to modify Bridgestone to eliminate the second three-way valve (60) and joint hose (66), resulting in a conventional tire repair kit meeting the limitations of the claims of the 110 Patent.” The magistrate judge denied SSI’s motion, noting that “the Federal Circuit has already considered and rejected obviousness in light of the combination of Eriksen and Bridgestone.”

Following a four-day trial, the jury found the asserted claims including claim 26 of the ’110 patent infringed and not invalid. The jury awarded $2,525,482 in lost profits and $255,388 in the form of a reasonable royalty for infringing sales for which TEK did not prove its entitlement to lost profits.

SSI then moved for a new trial on damages (or remittitur) and for JMOL on damages, invalidity, and noninfringement. The district court denied SSI’s motions for a new trial and for JMOL on invalidity and noninfringement. As to SSI’s motion for JMOL on damages, the district court denied the motion with respect to lost profits and granted it with respect to reasonable royalty. The district court also granted TEK’s motion for a permanent injunction. SSI appealed to the Federal Circuit.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit vacated the district court’s final judgment as to validity and reversed its denial of SSI’s motion for partial new trial on validity. In the interest of judicial economy, the Federal Circuit also reached the remaining issues on appeal including claim construction and infringement, and affirmed on those issues in the event the ’110 patent is found not invalid following the new trial.

This article focuses on the issues of the claim construction and infringement.

1. Claim Construction

(a) Fast-fit coupling

Review the district court’s claim construction de novo, and any underlying factual findings based on extrinsic evidence for clear error, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s claim construction, concluding that the intrinsic and extrinsic evidence in this case establishes that the term “conduit” recites sufficiently definite structure to avoid classification as a nonce term and agreed with the district court that SSI did not meet its burden to overcome the presumption against applying 35 U.S.C. 112, ¶ 6.

First, the Federal Circuit noted that SSI did not dispute that the elements connected via the conduits—i.e., the container, the compressor assembly, and the inflatable article (e.g., a tire)—each comprise definite structure, and that SSI did not dispute that the “hose” disclosed in the ’110 patent is structural.

Second, the Federal Circuit concluded that the ’110 patent (intrinsic evidence) clearly contemplates a conduit having physical structure. Indeed, the disclosed conduits serve to physically connect a container of sealing liquid to a compressor and to connect the compressor to tires such that “[t]he liquid is fed into the [tire] for repair by means of compressed air, e.g., by means of a compressor.” ’110 patent col. 1 ll. 13–14. Note that the cited portion in the parentheses is described in the “BACKGROUND ART” section of the specification without reference to any drawing in the patent.

Third, citing the applicant’s statement when adding new claim 26 to its patent application, “[n]ew claim 26 is similar to claim 10 but defines the connections in structural terms rather than ‘means for’ language,” the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court’s determination that the prosecution history establishes that the applicant intended for the term “conduit” to avoid the application of 35 U.S.C. 112, ¶ 6, with note that “[t]he subjective intent of the inventor when he used a particular term is of little or no probative weight in determining the scope of a claim,” but that is not necessarily true when the intent is “documented in the prosecution history.” Markman v. Westview Instruments, Inc., 52 F.3d 967, 985 (Fed. Cir. 1995) (en banc) (emphasis added).

Finally, the Federal Circuit indicated that extrinsic evidence also supports the conclusion. For example, dictionary definitions at or around the time of the invention confirm that the noun “conduit” denoted structure with “a generally understood meaning in the mechanical arts.” Greenberg v. Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc., 91 F.3d 1580, 1583 (Fed. Cir. 1996) (explaining that the dictionary definition of “detent” shows that a person skilled in the art would understand the term to connote structure); Webster’s Third New International Dictionary 474 (1993) (defining “conduit” as “a natural or artificial channel through which water or other fluid passes or is conveyed: aqueduct, pipe”); The New Oxford American Dictionary 358 (2001) (defining “conduit” as “a channel for conveying water or other fluid”).

(b) Outer casing connected to compressor

SSI also argues that because claim 26 requires that the “seat is part of the outer casing[,] . . . the outer casing connects the container to the compressor.”

Regarding the issue, the Federal Circuit indicated that its inquiry is limited to whether substantial evidence supports the jury’s infringement verdict under the issued claim construction, and did not reach whether the accused product infringes the asserted claims under SSI’s posited constructions because the district court expressly rejected SSI’s interpretation when determining that the term should have its plain and ordinary meaning, and because SSI did not appeal the district court’s claim construction order rejecting its interpretation of the plain and ordinary meaning.

2. Infringement (Product-to-Product Comparison)

SSI argued that the district court legally erred by allowing TEK, over SSI’s objections, to compare the accused product to TEK’s commercial embodiment during its closing argument.

While the Federal Circuit agreed with SSI’s assertion that to infringe, the accused product must meet all the limitations of the claim, the Court noted, “when a commercial product meets all the claim limitations, then a comparison [of the accused product] to that [commercial] product may support a finding of infringement.”

Regarding this case, the Federal Circuit stated that it cannot say that the district court abused its discretion by allowing the jury to hear the indirect product-to-product comparison, given that SSI’s own expert, Dr. King, acknowledged that he understood the TEK device to be an “embodying device” and to “practice[] the ’110 Patent,” and that certain statements made by SSI’s former executive, TEK’s counsel, and the inventor also suggest that TEK’s device is the commercial embodiment of the ’110 patent.

The Federal Circuit affirmed that the district court overruled SSI’s objections to certain alleged product-to-product comparisons in TEK’s closing argument because it determined that “SSI and its expert invited a product-to-product comparison by identifying TEK’s product as an embodiment of the invention, then drawing a contrast (albeit an unconvincing one) with SSI’s product.”

The Federal Circuit also affirmed that the district court, in its discretion, determined that the indirect comparison between TEK’s product and SSI’s product, in the context that it occurred, was not cause for a new trial. For the support of the affirmance, the Federal Circuit referred to the district court’s instruction directing the jury not to perform a product-to-product comparison to decide the issue of infringement (“You’ve heard evidence about both TEK’s product and SSI’s product. However, in deciding the issue of infringement, you may not compare SSI’s Accused Product to TEK’s product. Rather, you must compare SSI’s Accused Product to the claims of the ’110 Patent when making your decision regarding patent infringement.”). In the Federal Circuit’s view, the district court’s cautionary instructions are sufficient to mitigate any potential jury confusion or substantial prejudice to SSI due to the apparent product-to-product comparison.

In light of the above considerations, the Federal Circuit concluded that the district court did not abuse its discretion, and thus declined to reverse its denial of SSI’s motion for a new trial on infringement.

Takeaway

• The term “conduit” is now a member of examples of structural terms that have been found not to invoke 35 U.S.C. 112(f) or pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 112, paragraph 6. See MPEP 2181 [R-08.2017].

• Despite the maxim that to infringe a patent claim, an accused product must meet all the limitations of the claim, a comparison of the accused product to a commercial product that meets all the claim limitations could support a finding of infringement of the claim.

A case for importing limitation from specification into the claim

| April 6, 2019

Forest Laboratories, LLC v. Sigmapharm Laboratories, LLC

March 14, 2019

Before Prost, Dyk, and Moore (Opinion by Moore)

Summary

A district court’s narrowing claim interpretation that read a limitation from the specification into the claim may have helped a patent about an antipsychotic drug survive invalidity challenges. The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court’s claim interpretation, reasoning that repeated emphasis on the limitation in the specification and prosecution history supports the reading of the limitation into the claim. The Federal Circuit also agreed that, as a solution to an unrecognized problem, the claimed invention may not be obvious, particularly when there were no alternate, independent bases on which the prior art could be combined to make the claimed invention. Unfortunately, the district court’s lack of express findings on an unrelated proffered motivation to combine prompted the Federal Circuit to nevertheless vacate the district court’s nonobviousness determination and remand the case.

Details

Forest Laboratories, LLC makes and sells the drug, SAPHRIS®, for treating bipolar disorders and schizophrenia. The active ingredient in SAPHRIS® is the compound, asenapine. This compound is the subject matter of U.S. Patent No. 5,763,476 (“476 patent”), also owned by Forest Laboratories.

SAPHRIS® on average costs almost $1,500 for 60 tablets, and there are currently no generic alternatives. When a group of drug makers sought approval from the FDA to make generic versions of SAPHRIS®, Forest Laboratories accused them of infringing the 476 patent.

For our purpose, claim 1 of the 476 patent is of particular interest:

1. A pharmaceutical composition comprising as a medicinally active compound: trans-5-chloro-2-methyl-2,3,3a,12b-tetrahydro-1H-dibenz[2,3:6,7]oxepino[4,5,-c]pyrrole or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof; wherein the composition is a solid composition and disintegrates within 30 seconds in water at 37°C.

It is worth noting that claim 4 of the 476 patent recites a “method for treating tension, excitation, anxiety, and psychotic and schizophrenic disorders, comprising administering sublingually or buccally” the asenapine.

Among the issues on appeal, the Federal Circuit’s discussions on claim construction and nonobviousness of claim 1 are informative.

As to claim construction, the question was whether claim 1 should be limited to sublingually or buccally administered compositions, or as the accused infringers would argue, should cover any composition that meets the claimed disintegration profile.

The district court determined that claim 1 should be limited to sublingual or buccal compositions. And the Federal Circuit agreed.

Unlike claim 4, claim 1 does not expressly recite “sublingual or buccal” administrations. The original claim 1 did recite “[a] sublingual or buccal pharmaceutical composition…suitable for use in sublingual or buccal compositions”, but all the “sublingual or buccal” language was removed during prosecution.

At first glance, then, the district court’s claim interpretation would seem to contradict not only the plain language of the claims, and also the intrinsic evidence vis-à-vis the prosecution history.

However, both the district court and the Federal Circuit were able to draw for their claim interpretation from the specification and prosecution history of the 476 patent.

The 476 patent specification repeatedly uses “sublingual or buccal” to modify the “invention”. For example, the 476 patent is titled “sublingual or buccal pharmaceutical composition”, and statements like “the invention relates to a sublingual or buccal pharmaceutical composition” are peppered throughout the specification. The 476 patent also extolls sublingual and buccal treatments, and criticizes conventional peroral or oral treatments.

The Federal Circuit noted that “[w]hen a patent…describes the features of the ‘present invention’ as a whole, this description limits the scope of the invention” (quoting Verizon Servs. Corp. v. Vonage Holdings Corp., 503 F.3d 1295, 1308 (Fed. Cir. 2007). In addition, both the district court and the Federal Circuit cited UltimatePointer, LLC v. Nintendo Co., 816 F.3d 816 (Fed. Cir. 2016) to support their claim interpretation. In UltimatePointer, the court limited the claim term “handheld device” to a “direct-pointing device” (for example, a Wiimote), even though the claim language did not expressly contain such a limitation. “[T]he repeated description of the invention as a direct-pointing system, the repeated extolling of the virtues of direct pointing, and the repeated criticism of indirect pointing clearly point to the conclusion that the ‘handheld device’…is limited to a direct-pointing device.” Id. at 823-24.

The prosecution history of the 476 patent likewise repeatedly used “sublingual or buccal” to modify the claimed composition. Most notably, in interpreting the original claim 1, the Examiner took the position that the language “‘suitable for sublingually or buccal administration,’ does not result in a structural difference between the claimed invention and the prior art,” and the “the composition as claimed may be used for either mode of administration (sublingually or orally, rectally, etc.).” In response, the patentee amended claim 1 to define “suitability” to mean that “the composition is a solid composition and disintegrates within 30 seconds in water at 37°C”. This feature distinguished the claimed invention over the prior art:

The Office Action indicated that any composition whose physical characteristics make the composition unique to sublingual or buccal administration…would be allowable. Applicants submit that the distinguishing feature of disintegration time is exactly such a characteristic…It is this feature of rapid disintegration which distinguishes a sublingual composition from a peroral one and which makes the compositions of the present invention suitable to avoid the adverse effects observed with peroral administration….

To obtain the good effects of the compositions of the present invention, it is necessary that the medicine be delivered by sublingual or buccal administration.

The district court inferred from those statements the inventors’ intention to limit the claims to sublingual or buccal compositions. The Federal Circuit reached the same conclusion even without considering the prosecution history. Looking only at the specification, and in a rather attenuated logic, the Federal Circuit determined that since the specification describes the claimed disintegration time as defining “rapid disintegration”, and also describes “rapid disintegration” as a feature of sublingual/buccal composition, the claimed disintegration time must therefore limit the claim to “sublingual or buccal” compositions.

Based on the above interpretation, the district court and the Federal Circuit agreed that claim 1 of the 476 patent was not obvious.

Even though asenapine, the use of asenapine to treat schizophrenia, and sublingual and buccal administrations of drugs were separately known in the art, there was no motivation to combine the prior art to arrive at the 476 patent’s sublingual or buccal formulation.

The Federal Circuit noted a “problem/solution” basis for finding nonobviousness. “[W]here a problem was not known in the art, the solution to that problem may not be obvious”. “[S]olving an unrecognized problem in the art can itself be [a] nonobvious patentable invention, even where the solution is obvious once the problem is known.”

Here, the invention grew out of concerns over severe cardiotoxic side effects of oral asenapine, which caused cardiac arrest in some patients. This prompted the inventors to consider alternative routes of administration. However, the dangers of oral asenapine were unknown in the art at the time of invention. Large-scale clinical studies were even being conducted with conventional oral asenapine tablets.

In addition, the inventors found that the cardiotoxicity of oral asenapine was likely due to accumulation of unmetabolized asenapine. However, sublingual or buccal administrations were expected to produce more, not less, unmetabolized asenapine.

The district court found, and the Federal Circuit accepted, that since nothing in the prior art indicated that oral asenapine had problems, the person skilled in the art would not have been motivated to change the route of administration. Moreover, “it would not have been predictable or expected that sublingual administration would provide a solution to the problem of cardiotoxic effect.”

The accused infringers attempted to argue, as an alternate motivation to combine, the benefit of having more treatment options. However, the Federal Circuit dismissed this argument, because “a generic need for more antipsychotic treatment options did not provide a motivation to combine these particular prior art elements.”

The Federal Circuit did disagree with the district court on one thing—unexpected results. The district court found it unexpected that sublingual administrations of asenapine lacked the cardiotoxicity of the oral formulations, because the skilled person would have expected the contrary. However, if the problem was not known, then how could the solution to the problem be “unexpected”? There would have been no expectations. As the Federal Circuit explained, “[A] person of ordinary skill could not have been surprised that the sublingual route of administration did not result in cardiotoxic effects because the person of ordinary skill would not have been aware that other routes of administration do result in cardiotoxic effect”.

The fight, however, is not completely over. The accused infringers offered a different “motivation to combine” argument, based on whether sublingual or buccal administration would have addressed patient compliance problems. The Federal Circuit did not think the district court made sufficient express findings on this proffered motivation to combine, and for this reason, vacated the district court’s nonobviousness determinations and remanded the case.

The district court and the Federal Circuit’s “problem/solution” approach to nonobviousness in this case raised an interesting question. How does that approach reconcile with the established case law that any need or problem known in the field of endeavor at the time of invention and addressed by the patent can provide a reason for combining the prior art? The whole of MPEP 2144(IV) is dedicated to explaining how the motivation to combine can be for a purpose or problem different from that of the inventor.

The Federal Circuit answered that question in a recent, non-precedential decision in In re Conrad (Fed. Cir., March 22, 2019): “[C]ases found that the inventor’s discovery of and solution to an unknown problem weighed in favor of non-obviousness because the proffered reason to modify the prior art did not present a specific, alternate basis that was unrelated to the rationale behind the inventor’s reasons for making the invention.” Where the person skilled in the art would combine the prior art “for a reason independent from solving the problem identified by [the inventor]”, the fact that the invention solved an unrecognized problem may not lend as much patentable weight as it did in Forest Laboratories.

Takeaway

In this case, the narrower interpretation worked to the patentee’s advantage, particularly because the accused infringers had already conceded on the question of infringement. But such narrowing of the claim scope after the fact may not always be desirable. One may have preserved the validity of the patent, but is left with a negligible pool of potential infringers against whom to assert the patent.

Be mindful of how the invention is defined in the specification and during prosecution. Be careful with scope-limiting language such as “The present invention is…”, and absolute language such as “necessary”, “essential”, and “the distinguishing feature”.

Question the Examiner’s rationale for combining prior art. I have on several occasions seen Examiners use “more options” to rationalize a proposed combination of prior art. This may be a cop-out, because the Examiner may not have a specific, alternate basis for combining the prior art that is unrelated to the inventor’s reasons for making the invention. In that case, the nonobviousness of the invention may be formulated as the discovery of a solution to the “recognition of an unknown problem”.