Divided Claim Construction Leads to Reversal of Jury Verdict Against Alleged Infringer

| April 17, 2013

Saffran v. Johnson & Johnson

April 4, 2013

Panel: Lourie, Moore, and O’Malley. Opinion by Lourie. Concurrence Opinions by Moore and O’Malley.

Summary

The Federal Circuit reversed a $482 million jury verdict against Cordis, a member of the Johnson & Johnson family. The reversal came as a result of the Federal Circuit’s significant narrowing of the district court’s construction of two key claim limitations. One claim term was narrowed because the Federal Circuit found that the patentee’s arguments made during prosecution of the asserted patent, for the purpose of distinguishing over cited prior art, amounted to prosecution disclaimer. Meanwhile, a structure identified in the specification by the patentee as the corresponding structure to a means-plus-function limitation was disregarded as such, because the specification failed to link the identified structure to the recited function with sufficient specificity.

Details

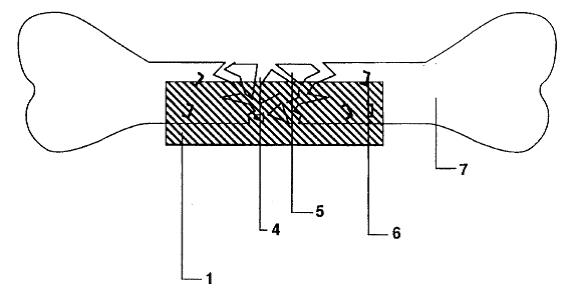

Dr. Bruce Saffran (“Saffran”) is the owner and sole inventor of U.S. Patent No. 5,653,760 (the “’760 patent”). The ’760 patent describes an apparatus for spurring the repair of bone fractures by containing tissue fragments and tissue growth-promoting macromolecules within the fracture site. A single-layered sheet, which is selectively impermeable to the macromolecules and the tissue fragments, is affixed to the injured bone tissues.

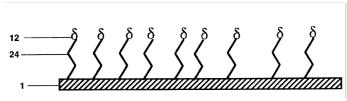

Drugs facilitating tissue regeneration can be bonded via hydrolysable chemical bonds to the inner surface of the single-layered sheet. This inner surface faces the injured tissues. Water molecules present at the fracture site causes lysing of the chemical bonds, which in turn releases and delivers the drugs into the fracture site. Bond lysis occurs at a constant rate, which enables the steady and controlled release of the drugs.

One particular embodiment of Saffran’s invention involves wrapping the single-layered sheet around an intravascular stent. The stent can then be inserted into a blood vessel to repair injured blood vessel wall.

Claim 1 is representative and reads as follows:

1. A flexible device for implantation into human or animal tissue to promote healing of a damaged tissue comprising:

a layer of flexible material that is minimally porous to macromolecules, said layer having a first and second major surface, the layer being capable of being shaped in three dimensions by manipulation by human hands . . .

the layer having material release means for release of an at least one treating material in a directional manner when said layer is placed adjacent to a damaged tissue,

the device being flexible in three dimensions by manipulation by human hands,

the device being capable of substantially restricting the through passage of at least one type of macromolecule therethrough

(emphasis added).

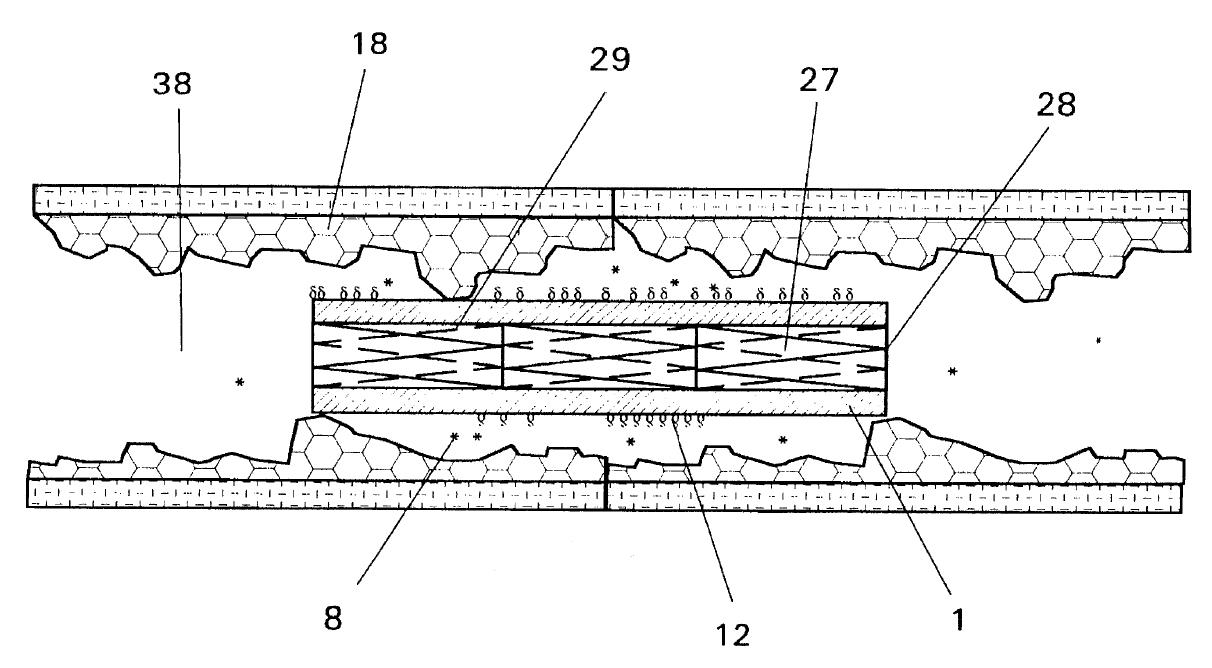

Cordis Corporation (“Cordis”), a member of the Johnson & Johnson family of companies, manufactures a drug-eluting coronary stent under the brand name, Cypher®. The stent comprises a metallic mesh coated with a microscopic layer of polymers. The macromolecular drug, sirolimus, is mixed with the polymer matrix, and is used to prevent plague buildup in coronary arteries. Following implantation of the stent, the drug diffuses out of the stent in a controlled release.

In 2007, Saffran filed suit against Cordis, alleging that Cypher® infringed the ’760 patent. A particularly contentious issue at trial was the construction of “device” and “release means” as recited in the ’760 patent. After a Markman hearing, the district court first interpreted the term “device” to be non-limiting preamble language that “merely gives a descriptive name to the set of limitations in the body of the claim.” The district court then continued on to construe the term to mean “a device having the limitations called out by the body of the claim.”

Next, the district court addressed the language, “release means for release of an at least one treating material in a directional manner.” The district court first found that the claim language is a means-plus-function limitation invoking 35 U.S.C. §112, sixth paragraph. Accordingly, the district court interpreted function of the claimed “release means” as “releas[ing] a drug preferentially toward the damaged tissue,” and defined the corresponding structure disclosed in the specification of the ’760 patent as “chemical bonds and linkages.”

The case proceeded to a jury trial, from which Saffran emerged a rich victor. The jury awarded Saffran a handsome amount upward of $590 million dollars ($482 million in damages, plus over $111 million in interest). At the time, the award was the ninth-largest patent verdict in the U.S. history. Naturally, Cordis appealed. The primary issue on appeal was the correct construction of claim terms, “device” and “release means.”

I. Claim Construction

1. “Device”

The Federal Circuit began by faulting the district court for interpreting “device” as merely non-limiting preamble language. Certainly, the district court was correct that term “device” must possess all the limitations set forth in the body of the claims. However, noting the appearance of the term “device” in the body of every claim of the ’760 patent, the Federal Circuit concluded that the term itself required construction beyond the explicitly recited limitations.

Relying primarily on the prosecution history of the ’760 patent, the Federal Circuit then went on to interpret “device” to narrowly mean a continuous sheet. During prosecution, one of the arguments that Saffran presented to distinguish over the cited art was that unlike the prior art invention, his device is a sheet. This argument, the Federal Circuit found, did not merely illuminate how the inventor understood his invention. Rather, Saffran’s arguments provided an affirmative definition for the term “device”. It is irrelevant that Saffran had also offered other grounds for overcoming the cited art.

The Federal Circuit acknowledged that “[t]o be sure, a prosecution disclaimer requires ‘clear and unambiguous disavowal of claim scope.’” However, a clear and unambiguous disavowal need not amount to an applicant’s explicit, affirmative disclaimer. Saffran’s assertion during prosecution that the claimed device is a sheet sufficed to limit “device” as recited in the claims of the ’760 patent to a continuous sheet.

2. “Release means”

On appeal, there was no dispute that the claim language, “release means for release of an at least one treating material in a directional manner,” should be construed as a means-plus-function pursuant to 35 U.S.C. §112, sixth paragraph. The district court’s interpretation of the function of the “release means” was also undisputed.

However, Cordis disagreed with the district court’s identification of the corresponding structure for carrying out the function. Cordis argued that the disclosure of the ’760 patent identified hydrolysable bonds as the only corresponding structure for the “release means.” Cordis further argued that there was inadequate disclosure in the ’760 patent to establish the more general “chemical bonds and linkages” as the corresponding structure.

Defending the district court’s interpretation, Saffran contended that one skilled in the art would have recognized “chemical bonds and linkages” as suitable structures for the claimed “release means.” The Federal Circuit ultimately sided with Cordis.

The Federal Circuit articulated that for the purpose of §112, sixth paragraph, a structure disclosed in the specification is a corresponding structure only if the specification or prosecution history clearly links or associates the structure to the function recited in the claim. The Federal Circuit indicated that the specification of the ’760 patent fully described the linkage between the treating material and the sheet as a hydrolysable bond. The specification even distinguished Saffran’s invention over the prior art on the basis of hydrolysable bonds.

However, the specification of the ’760 patent did not link any additional structures to the release function with sufficient specificity to satisfy §112, sixth paragraph. The Federal Circuit noted that the scattered and seemingly indeterminate use of the term “chemical bonds” throughout the specification failed to convey additional, specific corresponding structures separate and apart from hydrolysable bonds.

More importantly, as to Saffran’s contention that a skilled artisan would have understood the range of chemical bonds and linkages that could be used to perform the release function, the Federal Circuit seemed to suggest that such an argument would be an end run around §112, sixth paragraph. The Federal Circuit held that:

“A patentee cannot avoid providing specificity as to structure simply because someone of ordinary skill in the art would be able to devise a means to perform the claimed function. Under §112, ¶ 6, the question is not what structures a person of ordinary skill in the art would know are capable of performing a given function, but what structures are specifically disclosed and tied to that function in the specification” (emphasis added).

II. Infringement

Having determined that the district court misconstrued the claimed “device” and “release means,” the Federal Circuit went on to find that Cordis’ Cypher® stent did not infringe the ’760 patent. The Cypher® stent both lacked a continuous sheet covering the metallic mesh structure and lacked a drug affixed to the stent surface via hydrolysable bonds.

Concurrence opinions by Moore and O’Malley

Interestingly, the concurrence opinions both agreed that the jury verdict for Saffran should be reversed, but disagreed as to the correct claim construction. Basically, each member of the three-judge panel endorsed a different construction for the claim terms in question.

We begin with Judge Moore. Judge Moore agreed with the majority’s interpretation of “device,” but preferred the district court’s construction of the claimed “release means.” Pointing in particular to one passage in the specification of the ’760 patent, which described attaching a treating material “either mechanically or by chemical bond” to a surface of the claimed device, Judge Moore determined that this passage sufficiently associated the claimed “release means” with a chemical bond structure to satisfy §112, sixth paragraph. Judge Moore reasoned that §112, sixth paragraph requires only some link between a generic structural reference and the claimed function understandable to one skilled in the art. Judge Moore seemed to suggest that the majority had inappropriately and arbitrarily raised the level of specificity necessary to establish a corresponding structure under §112, sixth paragraph.

Meanwhile, Judge O’Malley took issue with the majority’s construction of the term “device,” opting for the district court’s construction of the term as something which comprises the limitations set out in the body of the claim. Judge O’Malley’s opinion focused on the fact that the specification of the ’760 patent broadly disclosed several embodiments that demonstrably did not include a continuous sheet. The breadth of the disclosure precluded limiting “device” to the one particular embodiment requiring a continuous sheet structure.

Judge O’Malley further questioned the majority opinion’s reliance on the prosecution history of the ’706 patent. The majority was faulted for elevating prosecution history to a prominence it did not deserve, while giving a short shrift to the specification. The Federal Circuit had previously held that prosecution history is less useful than specification for claim construction purposes, because “prosecution history represents an ongoing negotiation between the PTO and the applicant, rather than the final product, [and thus] often lacks the clarity of the specification.” Further, Judge O’Malley acknowledged that while Saffran had unambiguously disclaimed the alternative embodiments disclosed in the cited prior art, she was skeptical as to whether the prosecution history of the ’760 patent convincingly supported the finding that Saffran had also deliberately and unambiguously disclaimed all embodiments which excluded the continuous sheet structure.

Takeaway

- Every argument made during prosecution of a patent matters. Even ineffective or superfluous arguments may be used later as evidence of prosecution disclaimer, resulting in the unintended loss of claim scope.

- Relying on means-plus-function claim language continues to be fraught with the danger of inadequate disclosure. MPEP §2181(II) provides that a specification properly supports a means-plus-function limitation if “the corresponding structure of the means-plus-function limitation [is] disclosed in the specification itself in a way that one skilled in the art will understand what structure will perform the recited function.” Now, the Federal Circuit seems to also require that the specification link or associate a structure with the claimed function with “sufficient specificity.” However, what constitutes “sufficient specificity” is murky and unknowable.