The Federal Circuit declined to be bound by the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance by the Patent Office, but affirmed the Board’s conclusion of the ineligibility, which relied on the Guidance

| May 7, 2020

In re Rudy

April 24, 2020

Prost, Chief Judge, O’Malley and Taranto. Court opinion by Prost.

Summary

The Federal Circuit declined to be bound by the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance by the Patent Office, and instead followed the Supreme Court’s Alice/Mayo framework, and the Federal Circuit’s interpretation and application thereof. However, the Federal Circuit unanimously affirmed the Board’ affirmance of the Examiner’s rejection of claims 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, and 45–49 of the ’360 application as patent-ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101, which was fully relied on the Office Guidance.

Details

I. background

United States Patent Application No. 07/425,360 (“the ’360 application”), filed by Christopher Rudy on October 21, 1989 (before the signing of the 1994 Uruguay Round Agreements Act), is entitled “Eyeless, Knotless, Colorable and/or Translucent/Transparent Fishing Hooks with Associatable Apparatus and Methods.” After a lengthy prosecution of more than twenty years, including numerous amendments and petitions, four Board appeals, and a previous trip to the Federal Circuit where the obviousness of all claims then on appeal was affirmed (In re Rudy, 558 F. App’x. 1011 (Fed. Cir. 2014) (non-precedential)), claim 34, which the Board considered illustrative, reads as follows:

34. A method for fishing comprising steps of

(1) observing clarity of water to be fished to deter- mine whether the water is clear, stained, or muddy,

(2) measuring light transmittance at a depth in the water where a fishing hook is to be placed, and then

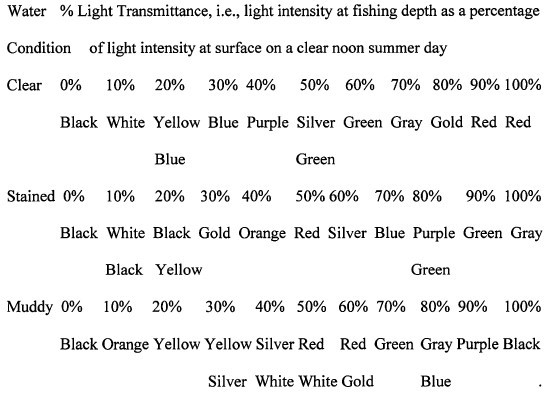

(3) selecting a colored or colorless quality of the fishing hook to be used by matching the observed water conditions ((1) and (2)) with a color or colorless quality which has been previously determined to be less attractive under said conditions than has undergone those pointed out by the following correlation for fish-attractive non-fluorescent colors:

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) affirmed the Examiner’s rejection of claims 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, and 45–49 of the ’360 application in the last Board appeal. The Board conducted its analysis under a dual framework for patent eligibility, purporting to apply both 1) “the two-step framework described in Mayo [Collaborative Ser- vices v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 566 U.S. 66 (2012)] and Alice [Corp. v. CLS Bank International, 573 U.S. 208 (2014)],” and 2) the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance, 84 Fed. Reg. 50 (Jan. 7, 2019) (“Office Guidance”), published by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“Patent Office”). Specifically, the Board concluded “[u]nder the first step of the Alice/Mayo framework and Step 2A, Prong 1, of [the] Office Guidelines” that claim 34 is directed to the abstract idea of “select[ing] a colored or colorless quality of a fishing hook based on observed and measured water conditions, which is a concept performed in the human mind.” The Board went on to conclude that “[u]nder the second step in the Alice/Mayo framework, and Step 2B of the 2019 Revised Guidance, we determine that the claim limitations, taken individually or as an ordered combination, do not amount to significantly more than” the abstract idea.

Mr. Rudy timely appealed, challenging both the Board’s reliance on the Office Guidance, and the Board’s ultimate conclusion that the claims are not patent eligible.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit unanimously affirmed the Board’ affirmance of the Examiner’s rejection of claims 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, and 45–49 of the ’360 application.

1. Office Guidance vs. Case Law

Mr. Rudy contended that the Board “misapplied or refused to apply . . . case law” in its subject matter eligibility analysis and committed legal error by instead applying the Office Guidance “as if it were prevailing law.”

The Federal Circuit agreed with Mr. Rudy, stating: “[w]e are not[] bound by the Office Guidance, which cannot modify or supplant the Supreme Court’s law regarding patent eligibility, or our interpretation and application thereof.” Interestingly, the Federal cited a non-precedential opinion to support its position: “As we have previously explained:

While we greatly respect the PTO’s expertise on all matters relating to patentability, including patent eligibility, we are not bound by its guidance. And, especially regarding the issue of patent eligibility and the efforts of the courts to determine the distinction between claims directed to [judicial exceptions] and those directed to patent-eligible ap- plications of those [exceptions], we are mindful of the need for consistent application of our case law.

Cleveland Clinic Found. v. True Health Diagnostics LLC, 760 F. App’x. 1013, 1020 (Fed. Cir. 2019) (non-precedential). ”

In conclusion, the Federal Circuit declared: “[t]o the extent the Office Guidance contradicts or does not fully accord with our caselaw, it is our caselaw, and the Supreme Court precedent it is based upon, that must control.”

2. Subject Matter Eligibility of Rudy’s Case

The Federal Circuit concluded that although a portion of the Board’s analysis is framed as a recitation of the Office Guidance, the Board’s reasoning and conclusion for Rudy’s case are nevertheless fully in accord with the relevant caselaw in this particular case.

To determine whether a patent claim is ineligible subject matter, the U.S. Supreme Court has established a two-step Alice/Mayo framework. In Step One, courts must determine whether the claims at issue are directed to a patent-ineligible concept such as an abstract idea. Alice, 573 U.S. at 208. In Step Two, if the claims are directed to an abstract idea, the courts must “consider the elements of each claim both individually and ‘as an ordered combination’ to determine whether the additional elements ‘transform the nature of the claim’ into a patent-eligible application.” Id. To transform an abstract idea into a patent-eligible application, the claims must do “more than simply stat[e] the abstract idea while adding the words ‘apply it.’” Id. at 221. At each step, the claims are considered as a whole. See id. at 218 n.3, 225.

a. Step One

With respect to claim 34, the Federal Circuit concluded, as the Board did, that the claim is directed to the abstract idea of selecting a fishing hook based on observed water conditions. Specifically, the Federal Circuit compared claim 34 with Elec. Power Grp., and reasoned that claim 34 requires nothing more than collecting information (water clarity and light transmittance) and analyzing that information (by applying the chart included in the claim), which collectively amount to the abstract idea of selecting a fishing hook based on the observed water conditions. See Elec. Power Grp., LLC v. Alstom S.A., 830 F.3d 1350, 1353–54 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (the Federal Circuit held in the computer context that “collecting information” and “analyzing” that information are within the realm of abstract ideas.).

The Federal Circuit disagreed with Mr. Rudy’s contention that claim 34’s preamble, “a method for fishing,” is a substantive claim limitation such that each claim requires actually attempting to catch a fish by placing the selected fishing hook in the water. The Federal Circuit reasoned that such an “additional limitation,” even if that were true, would not alter the conclusion because the character of claim 34 as a whole remains directed to an abstract idea.

The Federal Circuit also disagreed with Mr. Rudy’s contention that claim 34 is not directed to an abstract idea both because fishing “is a practical technological field . . . recognized by the PTO” and because he contends that observing light transmittance is unlikely to be performed mentally. Regarding the “practical technological field,” the Court reasoned that the undisputed fact that an applicant can obtain subject-matter eligible claims in the field of fishing is irrelevant to the fact that the claims currently before the Court are not eligible. Regarding the unlikeliness of the mental performance, the Court pointed our that the plain language of the claims encompasses such mental determination.

The Federal Circuit further rejected Mr. Rudy’s contention that, relying on the machine-or-transformation test, practicing claim 34 “acts upon or transforms fish” by transforming “freely swimming fish to hooked and landed fish” or by transforming a fishing hook “from one not having a target fish on it to one dressed with a fish when a successful strike ensues.” The Court declined to decide in this case whether the transformation from free fish to hooked fish is the type of transformation discussed in Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593, 604 (2010) and its predecessor cases. Instead, the Court stated that claim 34 does not actually recite or require the purported transformation that Mr. Rudy relies upon because, as Mr. Rudy’s explained, “landing a fish is never a sure thing. Many an angler has gone fishing and returned empty handed.”

b. Step Two

In the Step Two Analysis, the Court concluded that claim 34 fails to recite an inventive concept at step two of the Alice/Mayo test, and is thus not patent eligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101 because the three elements of the claim (observing water clarity, measuring light transmittance, and selecting the color of the hook to be used), either individually or as an ordered combination, do not amount to “‘significantly more than a patent upon the ineligible concept itself.’” The argument in the Step Two Analysis appears somewhat cursory.

c. The Remaining Claims

The Federal Circuit concluded that claim 38, the only other independent claim on appeal, is not patent-eligible as well.

Claim 38 begins with a method that is substantively identical to claim 34, but includes a slightly different chart for selecting the fishing hook color, and further includes only one additional limitation, which recites: “wherein the fishing hook used is disintegrated from but is otherwise connectable to a fishing lure or other tackle and has a shaft portion, a bend portion connected to the shaft portion, and a barb or point at the terminus of the bend, and wherein the fishing hook used is made of a suitable material, which permits transmittance of light therethrough and is colored to colorless in nature.”

The Court stated that the slightly different substance of claim 38’s chart does not render it patent eligible because the substance of claim 34’s hook color chart was not the basis of the eligibility determination. The Court further stated that its step-one analysis of claim 34 is equally applicable to claim 38 because, as described above, this limitation does not change the fact that the character of the claim, as a whole, is directed to an abstract idea.

The Court also affirmed the Board’s conclusions that dependent claims 35, 37, and 40 are not patent eligible, as each recites the physical attributes of the connection between the fishing hook and the fishing lure in ways not meaningfully distinct from claim 38.

The Court further affirm the Board’s conclusions regarding claims 45–49, which differ from the previously discussed claims only in that they mandate a specific color of fishing hook, which neither changes the character of the claims as a whole, nor provides an inventive concept distinct from the abstract idea itself.

Takeaway

· The case demonstrates that courts still stick to the comparative approach in Alice step one, instead of defining or categorizing the “abstract idea.” This approach is notably in contrast with that of the Patent Office, which follows the Office Guidance, dividing Alice step one into two inquiries: (i) evaluate whether the claim recites a judicial exception; and (ii) evaluate whether the judicial exception is integrated into a practical application if the claim recites a judicial exception.

· To be on the safe side for the purpose of drafting a patent specification including claim(s), which is robust to an invalidity defense under 35 U.S.C. § 101, the Supreme Court’s law regarding patent eligibility, and the Federal Circuit’s interpretation and application thereof, not the Office Guidance, shall be relied on.