Prosecution Refreshers – Incorporating Foreign Priority Application by Reference, Translations, Means-Plus-Function

| October 7, 2021

Team Worldwide Corp. v. Intex Recreation Corp.

Decided September 9, 2021

Opinion by: Chen, Newman, and Taranto

Summary:

The claimed “pressure controlling assembly” was found to be a means-plus-function claim element. Because the specification did not disclose any corresponding structure to perform at least one of the associated functions for this pressure controlling assembly, the claim was held to be indefinite. The specification did not disclose any corresponding structure because the portions of the foreign priority application (that disclosed corresponding structure) were omitted in the US application, and there was no incorporation by reference of the foreign priority application.

Procedural History:

This is a non-precedential Federal Circuit decision for an appeal from a PTAB post-grant review (PGR) decision. Intex petitioned for a PGR on Team Worldwide’s USP 9,989,979 patent (filed Aug. 29, 2014). The ‘979 patent is a divisional application of an earlier pre-AIA application. The ‘979 patent, filed after the March 16, 2013 effective date for AIA, is subject to AIA’s PGR unless each claim is supported in its pre-AIA parent application under 35 USC §112(a) for written description support and enablement. However, the earlier pre-AIA application at least did not have written description support for the claimed “pressure controlling assembly.” Thus, the ‘979 patent was subject to AIA’s post-grant review. The PTAB held that “pressure controlling assembly” is a means-plus-function (MPF) claim element subject to interpretation under 35 USC §112(f) and the ‘979 claims are invalid as indefinite under 35 USC §112(b) because there is no corresponding structure disclosed in the specification for at least one of the claimed functions thereof. The Federal Circuit affirmed.

Background:

The ‘979 patent relates to an inflator for an air mattress. Representative claim 1:

1. An inflating module adapted to an inflatable object comprising an inflatable body, the inflating module used in conjunction with a pump that provides primary air pressure and comprising:

a pressure controlling assembly configured to monitor air pressure in the inflatable object after the inflatable body has been inflated by the pump; and

a supplemental air pressure providing device,

wherein the pressure controlling assembly is configured to automatically activate the supplemental air pressure providing device when the pressure controlling assembly detects that the air pressure inside the inflatable object decreases below a predetermined threshold after inflation by the pump, and to control the supplemental air pressure providing device to provide supplemental air pressure to the inflatable object so as to maintain the air pressure of the inflatable object within a predetermined range.

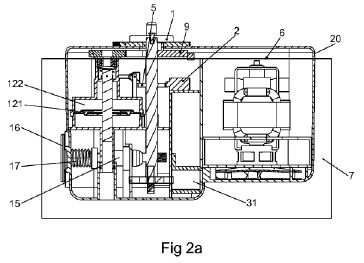

The ‘979 patent describes the pressure controlling assembly almost exclusively in functional terms, including the functions recited in claim 1. There is one sentence that states “[a]fter the supplemental air pressure providing device is in a standby mode, a pressure controlling assembly 121/122 as described starts monitoring air pressure in the inflatable object” (col. 4, lines 48-51). No explanation is provided about elements 121/122 shown in Fig. 2a:

Both the ‘979 and its parent application (having the same specification) claim foreign priority from CN 201010186302. However, neither US application incorporates the CN ‘302 application by reference.

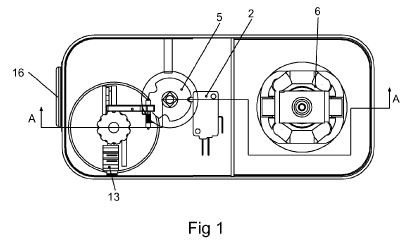

According to a translation of CN ‘302 application, CN ‘302 does describe an “air pressure control mechanism” that includes “air valve plate 121” and “chamber 122” which move in response to changing air pressure within the attached inflatable device. CN ‘302 further describes a switch 13, see Fig. 1 (same drawings in both CN ‘302 and the ‘979 patent and its parent):

According to CN ’302, as translated, “[w]hen the air pressure value inside the inflatable product is greater than the reset mechanism’s preset value, the air pressure control mechanism shifts upward, the second switch 13 is closed by the projection pressing against it, and the automatic reinflation mechanism halts reinflation” and “[w]hen the air pressure value inside the inflatable product is less than the reset mechanism’s preset value, the air pressure control mechanism shifts downward, the projection is removed from second switch 13 causing it to disconnect, and the automatic reinflation mechanism starts reinflation.”

Neither the ‘979 patent, nor its parent application, includes the above-noted structures of an air valve plate for reference number 121 nor the chamber for reference number 122. Neither US applications mention any switch 13 nor the above-noted operations involving the switch 13 for starting or stopping reinflation. Reference number 13 is not at all described in the ‘979 specification, nor in its parent’s specification.

The court also noted that the original specification in both the ‘979 patent and its parent application did not even mention reference numbers 121 and 122. It was added to the specification during prosecution to overcome an Examiner’s drawing objection for including those reference numbers in a drawing that were not described in the specification.

MPF Primers:

- If a claim does not recite the word “means,” it creates a rebuttable presumption that §112(f) does not apply.

- A presumption against applying §112(f) is overcome “if the challenger demonstrates that the claim term fails to recite sufficiently definite structure or else recites function without reciting sufficient structure for performing that function.” Williamson v. Citrix Online, LLC, 792 F.3d 1339, 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (en banc).

Decision:

Claim construction is reviewed de novo, considering the intrinsic record, i.e., the claims, specification, and prosecution history, and any extrinsic evidence.

For the claim itself, like the word “means,” the word “assembly” is a generic nonce word. “Like the claim term ‘mechanical control assembly’ in MTD Products, ‘the claim language reciting what the [pressure] control[ing] assembly is ‘configured to” do is functional,’ and thus the claim format supports applicability of §112(f).”

As for the specification, the court agrees with the PTAB that the specification’s “mere reference to items 121 and 122, without further description, does not convey that the term ‘pressure controlling assembly’ itself connotes sufficient structure.” The court also noted that the specification does not indicate that the patentee acted as his own lexicographer to define the “pressure controlling assembly” to be a structural term.

As for the prosecution history, the fact that the examiner cited prior art pressure sensors as disclosing the claimed “pressure controlling assembly” does not establish that the term itself connotes structure. While a pressure sensor may perform some of the functions of the “pressure controlling assembly,” the examiner’s reliance on a pressure sensor says nothing about the term itself connoting structure. The court also rejected giving weight to the fact that the examiner did not apply §112(f) for interpreting the subject term.

As for extrinsic evidence, Team’s expert testimony was deemed conclusory and unsupported by evidence. Team’s expert relied on a dictionary definition of “pressure control” – any device or system able to maintain, raise, or lower pressure in a vessel or processing system. However, such a definition sheds no light on “pressure controlling assembly” being used in common parlance to connote structure. Even the purported admissions by Intex’s expert (i.e., that the term controls pressure and is an assembly, that devices exist that sense or control pressure, and that a cited prior art reference depicted “an apparatus that controls the pressure”) merely indicates that devices existed that can perform some of the functions of the “pressure controlling assembly.” However, none of the experts’ testimony establish that “pressure controlling assembly” is “used in common parlance or by [skilled artisans] to designate a particular structure or class of structures.”

As for prior art references that refer to a “pressure controlling assembly,” the court agreed with the PTAB’s assessment that such extrinsic evidence “demonstrates, at best, that the term is used as a descriptive term across a broad spectrum of industries, having a broad range of structures. The record does not include sufficient evidence to demonstrate that the term ‘pressure controlling assembly’ is used in common parlance or used to designate a particular structure by [the skilled artisan].”

As for the functions claimed for the “pressure controlling assembly,” there was no dispute:

- monitoring air pressure in the inflatable object after the inflatable body has been inflated by the pump;

- detecting that the air pressure inside the inflatable object decreases below a predetermined threshold after inflation by the pump;

- automatically activating the supplemental air pressure providing device when the pressure controlling assembly detects that the air pressure inside the inflatable object decreases below the predetermined threshold after inflation by the pump; and

- controlling the supplemental air pressure providing device to provide supplemental air pressure to the inflatable object so as to maintain the air pressure of the inflatable object within a predetermined range.

The court agrees with the PTAB that the patent fails to disclose any corresponding structure for at least #3. Team’s expert’s conclusory testimony that a skilled artisan would recognize that 121 and 122 in Fig. 2a interacts with element 13 in Fig. 1 to activate the supplemental air pressure providing device is not supported by any evidence. Nothing in the patent describes 13 to be a switch, much less how it interacts with 121 and 122, whatever those are.

As for the fact that CN ‘302 is part of the prosecution history, the court noted that the content of any document or reference submitted during prosecution by itself is not sufficient to remedy this missing disclosure of corresponding structure. In reference to B. Braun Medical, Inc. v. Abbott Lab., 124 F.3d 1419, 1424 (Fed. Cir. 1997), Braun’s reference to the “prosecution history” is in reference to affirmative statements made by the applicant during prosecution (such as in an Amendment or in a sworn declaration regarding the relationship between something in a drawing and a claimed MPF claim element) linking or associating corresponding structure with a claimed function. “[W]e decline to hold that a Chinese-language priority document, whose potentially relevant disclosure was omitted from the United States patent application family, provides a clear link or association between the claimed ‘pressure controlling assembly’ and any structure recited or disclosed in the ‘979 patent.”

Takeaways:

- This case is a good refresher for MPF interpretation.

- 37 CFR 1.57 addresses the situation where there is an inadvertent omission of a portion of the specification or drawings, by allowing a claim for foreign priority to be considered an incorporation by reference as to any inadvertently omitted portion of the specification or drawings from that foreign priority application. 37 CFR 1.57(a) (pre-AIA) would apply to the parent application of the ‘979 patent. 37 CFR 1.57(b) (AIA) would apply to the application leading to the ‘979 patent. However, any amendment made pursuant to 37 CFR 1.57 must be made before the close of prosecution. It is unclear why the applicant did not use the provisions of 37 CFR 1.57 in this case. Once the application is issued into a patent, as was the case here, the incorporation by reference provisions of 37 CFR 1.57 no longer apply. As noted in MPEP 217(II)(E), “In order for the omitted material to be included in the application, and hence considered to be part of the disclosure, the application must be amended to include the omitted portion. Therefore, applicants can still intentionally omit material contained in the prior-filed application from the application containing the priority or benefit claim without the material coming back in by virtue of the incorporation by reference of 37 CFR 1.57(b). Applicants can maintain their intent by simply not amending the application to include the intentionally omitted material.” Presumably, because the applicant for the ‘979 patent and its parent never took advantage of 37 CFR 1.57 during prosecution, the missing subject matter was treated as “intentionally omitted material” and does not come back into the patent by virtue of 37 CFR 1.57.

- The specification of the ‘979 patent and of its parent did not include any incorporation by reference of its foreign priority application. The applicant also did not take advantage of 37 CFR 1.57 during prosecution (see above). Accordingly, the foreign priority application was deemed “omitted from the United States patent application family.” And, just having it in the file wrapper at the USPTO is still not enough. The applicant, during prosecution, must correct any missing link between any MPF claim elements and its corresponding structure in the specification. Here, IF the Chinese priority application had been incorporated by reference or IF 37 CFR 1.57(a) (pre-AIA) and 37 CFR 1.57(b) (AIA) were used, an amendment to the specification to ADD inadvertently omitted English language translations of the corresponding structure from the priority application could have been submitted. Such amendments to the specification would not be deemed “new matter” because of the incorporation by reference of the foreign priority application.

- Always check the English language translation. It seems odd that no one noticed the omission of any description of the elements 121, 122, and 13 from the Chinese priority application. During the prosecution of the parent and the ‘979 patent, the Examiner identified at least a dozen different reference numbers that were not described in the specification. When preparing an application, or translating one, the specification should be checked for a description for each and every reference number used in the drawings.

Tags: Foreign Priority > Incorporation by reference > means-plus-function > translation

Be careful in translating foreign applications into English, particularly with respect to uncommon terms

| September 18, 2020

IBSA Institut Biochimique, S.A., Altergon, S.A., IBSA Pharma Inc. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc.

July 31, 2020

Prost (Chief Judge), Reyna, and Hughes. Opinion by Prost.

Summary

In a U.S. application claiming priority to an Italian application, the term “semiliquido” was translated as “half-liquid.” This term was found to be indefinite, in view of a lack of a clear meaning in the art, as well as the statements of the prosecution history and specification. Further, attempts to argue that the term “half-liquid” should be interpreted as “semi-liquid” failed due to inconsistencies with the specification.

Details

IBSA is the owner of U.S. Patent No. 7,723,390, which claims priority to an Italian application. Claim 1 of the ‘390 patent is as follows:

1. A pharmaceutical composition comprising thyroid hormones or their sodium salts in the form of either:

a) a soft elastic capsule consisting of a shell of gelatin material containing a liquid or half-liquid inner phase comprising said thyroid hormones or their salts in a range between 0.001 and 1% by weight of said inner phase, dissolved in gelatin and/or glycerol, and optionally ethanol, said liquid or half-liquid inner phase being in direct contact with said shell without any interposed layers, or

b) a swallowable uniform soft-gel matrix comprising glycerol and said thyroid hormones or their salts in a range between 0.001 and 1% by weight of said matrix.

Teva filed an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification asserting that the patent is invalid. In particular, Teva asserted that claim 1 is invalid as being indefinite. Upon filing of the ANDA, IBSA filed suit against Teva.

The key issue in this case is the meaning of the term “half-liquid.” IBSA asserted that this term should mean “semi-liquid, i.e., having a thick consistency between solid and liquid.” Meanwhile, Teva argued that the term is either invalid, or should be interpreted as a “non-solid, non-paste, non-gel, non-slurry, non-gas substance.”

District Court

At the district court, all parties agreed that the intrinsic record does not define the term “half-liquid.” However, IBSA asserted that its construction is supported by intrinsic evidence, including the Italian priority application. The Italian priority application used the term “semiliquido” at all places where the ‘390 patent used the term “half-liquid.” In 2019, IBSA obtained a certified translation in which “semiliquido” was translated as “semi-liquid.” IBSA asserted that “semi-liquid” and “half-liquid” would be understood as synonyms.

However, the district court noted that there were other differences between the Italian priority application and the ‘390 patent specification, beyond the “semiliquido”/“half-liquid” difference. These differences included the “Field of Invention” and “Prior Art” sections. Because of these other differences, the district court concluded that the terminology in the U.S. specification reflected the Applicant’s intent, and that any difference was deliberate.

Furthermore, the district court noted that during prosecution, there was at one point a dependent claim using the term “semi-liquid” which was dependent on an independent claim using the term “half-liquid.” Even though the term “semi-liquid” was eventually deleted, this was interpreted as evidence that the terms are not synonymous.

Additionally, the specification cited to pharmaceutical references that used the term “semi-liquid.” According to the district court, this shows that the Applicant knew of the term “semi-liquid,” but chose to use the term “half-liquid” instead.

Finally, all extrinsic evidence was considered by the district court to be unpersuasive. The extrinsic evidence used the term “half-liquid” in a different context than the present application. As such, the district court concluded that the term “half-liquid” was “exceedingly unlikely” to be a term of art at the time of filing.

Next, the district court analyzed whether a skilled artisan would nevertheless be able to determine the meaning of the term “half-liquid.” First, the court noted that the claims do not clarify what qualifies as a half liquid, other than the fact that it is neither liquid nor solid. The district court concluded that one skilled in the art would only understand “half-liquid” to be something that is not a gel or paste. This conclusion was based on a passage in the specification that stated:

In particular, said soft capsule contains an inner phase consisting of a liquid, half-liquid, a paste, a gel, an emulsion, or a suspension comprising the liquid (or half-liquid) vehicle and the thyroid hormones together with possible excipients in suspension or solution.

Additionally, during prosecution, the Applicant responded to an obviousness rejection by including the statement that the claimed invention “is not a macromolecular gel-lattice matrix” or a “high concentration slurry.” As such, the Applicant disclaimed these from the scope of “half-liquid.”

Finally, the district court commented on the expert testimony. IBSA’s expert had “difficulty articulating the boundaries of ‘half-liquid’” during his deposition. Meanwhile, Teva’s expert stated that “half-liquid is not a well-known term in the art.”

Based on the above, the district court concluded that one having ordinary skill in the art would find it impossible to know “whether they are dealing with a half-liquid within the meaning of the claim,” and concluded that the claims are invalid as being indefinite.

CAFC

The CAFC agreed with the district court on all points. First, the CAFC agreed that the claim language does not clarify the issue. Rather, the claim language only clarifies that “half-liquid” is not the same as liquid.

As to the specification, the CAFC agreed with the district court that the portion of the specification noted above clarifies that “half-liquid” cannot mean a gel or paste. Moreover, the CAFC cited another passage, which refers to “soft capsules (SEC) with liquid, half-liquid, paste-like or gel-like inner phase.” The CAFC concluded that the use of the word “or” in these passages shows that “half-liquid” is an alternative to the other members of the list, such as pastes and gels. Meanwhile, since gels and pastes have a thick consistency, IBSA’s proposed claim construction is in contradiction with these passages of the specification.

Additionally, the CAFC refuted IBSA’s argument that the specification includes passages that are at odds with the description of “half-liquid” as an alternative to pastes and gels. These passages include:

…an SEC capsule containing an inner phase consisting of a paste or gel comprising gelatin and thyroid hormones or pharmaceutically acceptable salts thereof…in a liquid or half liquid.

However, this argument conflates the inner phase and the vehicle within the inner phase, and does not explain why these are the same.

Additionally, the CAFC noted that the specification includes a list of examples of liquid or half-liquid vehicles, and a reference to a primer on making “semi-liquids.” However, even if some portions of the specification could support the position that “half-liquid” and “semi-liquid” are synonyms, the specification fails to describe the boundaries of “half-liquid.”

Next, the CAFC discussed the prosecution history. As in the district court, IBSA asserted that “half-liquid” means “semi-liquid.” This was because the term “half-liquid” was used in all places where “semiliquido” was used, and a certified translation showed that “semiliquido” is translated as “semi-liquid.”

The CAFC agreed the use of “half-liquid” was intentional, relying on not only the differences between the Italian application and the U.S. application noted by the district court, but others as well. In particular, claim 1 of the U.S. application differed from claim 1 of the Italian application, and incorporated an embodiment not found in the Italian application. Further, the Italian application does not use the term “gel” in the first passage noted above.

The CAFC also agreed with the district court that the temporary presence of a claim reciting “semi-liquid” dependent on a claim reciting “half-liquid” further demonstrates that these terms are not synonymous.

Finally, the CAFC reviewed the extrinsic evidence. The CAFC noted the IBSA’s expert’s inability to explain the boundaries of the term “half-liquid.” The CAFC also pointed out that only one dictionary of record had a definition including the term “half liquid,” and this was a non-scientific dictionary. This dictionary defined “semi-liquid” as “Half liquid; semifluid.” But, IBSA’s expert stated that “semifluid” and “half-liquid” are not necessarily the same.

Further, although other patents using the term “half-liquid” were cited, these patents used the term in a different context, and thus were not helpful to define the term in the context of the ‘390 patent. IBSA’s expert acknowledged the lack of any other literature such a textbook or a peer-reviewed journal using the term “half-liquid.” Additionally, IBSA’s expert stated that he was uncertain about whether his construction of “half-liquid” would exclude gels or slurries.

Based on the above, the CAFC concluded that the term “half-liquid” does not have a definite meaning. As such, the claim is invalid as failing to comply with §112.

Takeaways

-When translating a specification from a foreign language to English, it is preferable that the specifications are as close to identical as possible.

-If there are differences between a foreign language specification and the U.S. specification, these differences should ideally be limited to non-technical portions of the specification.

-If using a term that is not widely used, it is recommended to clearly define this term in the record. Failure to do so may result in the term being interpreted in an unintended manner, or worse, the term being considered indefinite.

-Where there are discrepancies between a foreign priority application and a US application, such differences may be interpreted as intentional.