File your patent application before attending a trade show to showcase your products

| May 26, 2023

Minerva Surgical, Inc. v. Hologic, Inc., Cytyc Surgical Products, LLC

Decided: February 15, 2023

Summary:

Minerva Surgical, Inc. sued Hologic, Inc. and Cytyc Surgical Products, LLC in the District of Delaware for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 9,186,208 (“the ’208 patent”). Hologic moved for summary judgment of invalidity, arguing that the ’208 patent claims were anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b). The district court granted summary judgment that the asserted claims are anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) because the patented technology was “in public use,” and the technology was “ready for patenting.” The Federal Circuit held that the district court correctly determined that Minerva’s disclosure of their constituted the invention being “in public use,” and that the device was “ready for patenting.” Therefore, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s grant of summary judgment.

Details:

Minerva Surgical, Inc. sued Hologic, Inc. and Cytyc Surgical Products, LLC in the District of Delaware for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 9,186,208 (“the ’208 patent”).

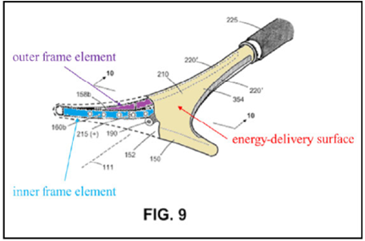

The ’208 patent is directed to surgical devices for a procedure called “endometrial ablation” for stopping or reducing abnormal uterine bleeding. This procedure includes inserting a device having an energy-delivery surface into a patient’s uterus, expanding the surface, energizing the surface to “ablate” or destroy the endometrial lining of the patient’s uterus, and removing the surface.

The application for the’208 patent was filed on November 2, 2021 and claims a priority date of November 7, 2011. Therefore, the critical date for the ’208 patent is November 7, 2010.

The ’208 patent

Independent claim 13 is a representative claim:

A system for endometrial ablation comprising:

an elongated shaft with a working end having an axis and comprising a compliant energy-delivery surface actuatable by an interior expandable-contractable frame;

the surface expandable to a selected planar triangular shape configured for deployment to engage the walls of a patient’s uterine cavity;

wherein the frame has flexible outer elements in lateral contact with the compliant surface and flexible inner elements not in said lateral contact, wherein the inner and outer elements have substantially dissimilar material properties.

The appeal focused on the claim term, “the inner and outer elements have substantially dissimilar material properties” (“SDMP” term”).

District Court

After discovery, Hologic moved for summary judgment of invalidity, arguing that the ’208 patent claims were anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b).

The district court granted summary judgment that the asserted claims are anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) because of the following reasons:

First, the patented technology was “in public use” because Minerva disclosed fifteen devices (“Aurora”) at an event, where Minerva showcased them at a booth, in meeting with interested parties, and in a technical presentation. Also, Minerva did not disclose them under any confidentiality obligations.

Second, the technology was “ready for patenting” because Minerva created working prototypes and enabling technical documents.

Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit reviewed a district court’s grant of summary judgment under the law of the regional circuit (Third Circuit).

The Federal Circuit held that “the public use bar is triggered ‘where, before the critical date, the invention is [(1)] in public use and [(2)] ready for patenting.’”

The “in public use” element is satisfied if the invention “was accessible to the public or was commercially exploited” by the invention.

“Ready for patenting” requirement can be shown in two ways – “by proof of reduction to practice before the critical date” and “by proof that prior to the critical date the inventor had prepared drawings or other descriptions of the invention that were sufficiently specific to enable a person skilled in the art to practice the invention.”

The Federal Circuit held that disclosing the Aurora device at the event (American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (“AAGL 2009”)) constituted the invention being “in public use” because this event included attendees who were critical to Minerva’s business, and Minerva’s disclosure of their devices included showcasing them at a booth, in meeting with interested parties, and in a technical presentation.

The Federal Circuit noted that AAGL 2009 was the “Super Bowl” of the industry and was open to the public, and that Minerva had incentives to showcase their products to the attendees. Also, Minerva sponsored a presentation by one of their board members to highlight their products and pitched their products to industry members, who were able to see how they operate.

The Federal Circuit also noted that there were no “confidentiality obligations imposed upon” those who observed Minerva’s devices, and that the attendees were not required to sign non-disclosure agreements.

The Federal Circuit also held that Minerva’s Aurora devices at the event disclosed the SDMP term because Minerva’s documentation about this device from before and shortly after the event disclosed this device having the SDMP terms or praises benefits derived from this device having the SDMP technology.

The Federal Circuit held that the record clearly showed that Minerva reduced the invention to practice by creating working prototypes that embodied the claim and worked for the intended purpose.

The Federal Circuit noted that there was documentation “sufficiently specific to enable a person skilled in the art to practice the invention” of the disputed SDMP term. Here, the documentation included the drawings and detailed descriptions in the lab notebook pages disclosing a device with the SDMP term.

Therefore, the Federal Circuit held that the district court correctly determined that Minerva’s disclosure of the Aurora device constituted the invention being “in public use” and that the device was “ready for patenting.”

Accordingly, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s grant of summary judgment because there are no genuine factual disputes, and Hologic is entitled to judgment as a matter of law that the ’208 patent is anticipated under the public use bar of § 102(b).

Takeaway:

- File your patent application before attending a trade show to showcase your products.

- Have the attendees of the trade show sign non-disclosure agreements, if necessary.

Tags: 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) > confidentiality > critical date > enablement > pre-AIA > prototype > public use > reduction to practice > summary judgment

The applicants’ statement during the prosecution may play a critical role for claim construction

| July 4, 2022

Sound View Innovations, LLC v. Hulu, LLC

Decided: May 11, 2022

Prost, Mayer (Sr.) and Taranto. Court opinion by Taranto.

Summary

On appeals from the district court for summary judgment of noninfringement of a patent, directed to a method of reducing latency in a network having a content server, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s construction of the down-loading/retrieving limitation solely on the basis of prosecution history, but the Court rejected the district court’s determination that “buffer” cannot cover “a cache,” and vacated the district court’s grant of summary judgment and remanded for further proceedings.

Details

I. Background

(i) The Patent in Dispute

Sound View Innovations, LLC (“Sound View”) owns now-expired U.S. Patent No. 6,708,213 (“the ’213 patent”), which describes and claims “methods which improve the caching of streaming multimedia data (e.g., audio and video data) from a content provider over a network to a client’s computer.” Claim 16 of the ’213 patent provides as follows:

16. A method of reducing latency in a network having a content server which hosts streaming media (SM) objects which comprise a plurality of time-ordered segments for distribution over said network through a plurality of helpers (HSs) to a plurality of clients, said method comprising:

receiving a request for an SM object from one of said plurality of clients at one of said plurality of helper servers;

allocating a buffer at one of said plurality of HSs to cache at least a portion of said requested SM object;

downloading said portion of said requested SM object to said requesting client, while concurrently retrieving a remaining portion of said requested SM object from one of another HS and said content server (the “downloading/retrieving limitation”); and

adjusting a data transfer rate at said one of said plurality of HSs for transferring data from said one of said plurality of helper servers to said one of said plurality of clients (emphasis added).

During the prosecution, the examiner rejected original claim 16—which was identical to issued claim 16 except that it lacked the downloading/retrieving limitation—as anticipated over DeMoney (U.S. Patent No. 6,438,630). To overcome the rejection, the applicants amended the claim to add the downloading/retrieving limitation. The applicants explained that support for the added limitation is found in the applicants’ specification, pointing to the portion of the specification that shows concurrent downloading and retrieval involving a single buffer (emphasis added). In fact, the specification nowhere says that the invention includes use of separate buffers for the concurrent downloading and retrieving functions, and it nowhere illustrates or describes such an embodiment, in which different buffers are involved in con- current downloading of one portion and retrieving of a remaining portion of the same SM object in response to a given client’s request.

(ii) The District Court

Sound View sued Hulu, LLC (“Hulu”) for infringement of six Sound View patents including the ’213 patent in the United States District Court for the Central District of California (“the district court”). As the case proceeded, only claim 16 of the ’213 patent remained at issue.

It was undisputed that the accused edge servers— the edge servers Sound View identified as the “helper servers” for its infringement charge—do NOT download and retrieve subsequent portions of the same SM object in the same buffer (emphasis added).

Sound View alleged, among other things, that, under Hulu’s direction, when an edge server receives a client request for a video not already fully in the edge server’s possession, and obtains segments of the video seriatim from the content server (or another edge server), the edge server transmits to the Hulu client a segment it has obtained while concurrently retrieving a remaining segment.

The district court agreed with Hulu’s argument that the applicants’ statements accompanying the amendment in the prosecution disclaimed the full scope of the downloading/retrieving limitation, and that the downloading/retrieving limitation thus required that the same buffer in the helper server—the one allocated in the preceding step—host both the portion sent to the client and a remaining portion retrieved concurrently from the content server or other helper server (emphasis added).

In reliance on the construction, Hulu then sought summary judgment of non-infringement of claim 16, arguing that it was undisputed that, in the edge servers of its content delivery networks, no single buffer hosts both the video portion downloaded to the client and the retrieved additional portion. Sound View countered that there remained a factual dispute about whether “caches” in the edge servers met the concurrency limitation as construed. The district court held, however, that a “cache” could not be the “buffer” that its construction of the down- loading/retrieving limitation required, and on that basis, it granted summary judgment of non-infringement. A final judgment followed.

Sound View timely appealed.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit (“the Court”) affirmed the district court’s construction of the down-loading/retrieving limitation. but the Court rejected the district court’s determination that “buffer” cannot cover “a cache,” and vacated the district court’s grant of summary judgment and remanded for further proceedings.

Claim Construction (the downloading/retrieving limitation)

The Court first noted that this is not a case in which the other intrinsic evidence—the claim language and specification—establish a truly plain meaning contrary to the meaning assertedly established by the prosecution history because the downloading/retrieving limitation, which does not expressly refer to “buffers,” contains no words affirmatively making clear that different buffers in the helper server may be used for the sending out to clients of one portion of the SM object and the receiving of a retrieved remaining portion.

The Court viewed the prosecution history as establishing that the applicants made clear that the applicants’ invention concurrently empties and fills the buffer, while the DeMoney reference teaches filling the buffer only after the buffer is empty,” citing column 12, lines 28–40 of DeMoney (emphasis added).

Based on the applicants’ statements, the Court agreed with the district court that the applicants limited claim 16 to using the same buffer for the required concurrent downloading and retrieval of portions of a requested SM object.

Summary Judgment of Non-Infringement

After the district court adopted its “buffer”-requiring claim construction of the downloading/retrieving limitation, it granted summary judgment of non-infringement, concluding that accused-system components called “caches”—on which Sound View relied for its allegation of infringement under the court’s claim construction—could not be the required “buffers.” The district court relied for its conclusion on the ’213 patent’s references to its described “buffers” and “caches” as distinct physical components. To support the conclusion, the district court noted that the ’213 patent describes buffers and caches in different locations: The patent defines “cache” as “a region on the computer disk that holds a subset of a larger collection of data,” and although the patent does not define “buffer,” it describes “ring buffers” located “in the memory” of the HS.

However, the Court stated that the district court’s construction here was inadequate for the second step of an infringement analysis (comparison to the accused products or methods) because it did not adopt an affirmative construction of what constitutes a “buffer” in this patent. More specifically, the Court stated that the district court did not decide, and the record does not establish, that “cache” is a term of such uniform meaning in the art that its meaning in the ’213 patent must be relevantly identical to its meaning when used by those who labeled the pertinent components of the accused edge servers. The Court thus concluded that, in the absence of such a uniformity-of-meaning determination, the district court’s conclusion that the ’213 patent distinguishes its buffers and caches is insufficient to support a determination that the accused-component “caches” are outside the “buffers” of the ’213 patent. What was needed was an affirmative construction of “buffer”— which could then be compared to the accused-component “caches” based on more than a mere name.

For an additional reason for the further affirmative construction, the Court pointed out that, even in the ’213 patent, the terms “buffer” and “cache” do not appear to be mutually exclusive, but instead seem to have at least some overlap in their coverage given that the disputed claim describes “allocating a buffer . . . to cache” a portion of the SM object, and that the specification explains that “the ring buffer . . . operates as a type of short term cache” because it is capable of servicing multiple client requests within a certain time interval (emphasis added).

Takeaway

· Claim construction: The applicants’ statement during the prosecution may play a critical role for claim construction if the claim language and specification do not establish a truly plain meaning of a disputed term contrary to the meaning assertedly established by the prosecution history.

· Summary Judgment: Portions of the specification may provide genuine issue of material fact for denial of summary judgment (in this case, the embodiment describes buffers and caches in different locations while the disputed claim provides “allocating a buffer . . . to cache”)

Claim construction of a non-functional term in an apparatus claim; proof of vitiation against infringement under the doctrine of equivalents

| March 29, 2021

Edgewell Personal Care Brands, LLC v. Munchkin, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2021) (Case No. 2020-1203)

March 9, 2021

Newman, Moore, and Hughes. Court opinion by Moore

Summary

On appeals from the district court for summary judgment of noninfringement of two patents, both directed to a cassette to be installed when a diaper pail system is in use, the Federal Circuit unanimously vacated the summary judgment of noninfringement of one patent because of erroneous claim construction, with caution that it is usually improper to construe non-functional claim terms in apparatus claims in a way that makes infringement or validity turn on the way an apparatus is later put to use. Furthermore, the Federal Circuit unanimously reversed the summary judgment of noninfringement of the other patent under the doctrine of equivalents because of erroneous application of the vitiation theory in the context of summary judgment, with caution that courts should be cautious not to shortcut the inquiry for infringement under the doctrine of equivalents by identifying a ‘binary’ choice in which an element is either present or ‘not present.’”

Details

I. Background

(i) The Patents in Dispute

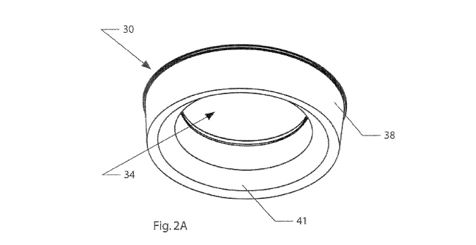

U.S. Patent Nos. 8,899,420 (“the ’420 patent”) and 6,974,029 (“the ’029 patent”) are directed to a cassette to be installed when a diaper pail system is in use.

The ’420 patent is directed to a cassette with a “clearance” located in a bottom portion of the cassette. Claim 1 is the representative of the ’420 patent, which recites:

1. A cassette for packing at least one disposable object, comprising: an annular receptacle including an annular wall delimiting a central opening of the annular receptacle, and a volume configured to receive an elongated tube of flexible material radially outward of the annular wall; a length of the elongated tube of flexible material disposed in an accumulated condition in the volume of the annular receptacle; and an annular opening at an upper end of the cassette for dispensing the elongated tube such that the elongated tube extends through the central opening of the annular receptacle to receive disposable objects in an end of the elongated tube,

wherein the annular receptacle includes a clearance in a bottom portion of the central opening, … (emphasis added).

Fig. 2A of the ’420 patent, reproduced below, illustrates a bottom perspective view of a cassette 30 to be used with an apparatus 10 (not shown in the figure) for packaging disposable objects (34: a central opening; 38: a bottom annular receptacle; a chamfer clearance 41).

The ’029 patent is directed to a cassette with a cover extending over pleated tubing housed therein. Claim 1 is the representative of the ’029 patent, which recites:

1. A cassette for use in dispensing a pleated tubing comprising:

an annular body having a generally U shaped cross-section defined by an inner wall, an outer wall and a bottom wall joining a lower part of said inner and outer walls, said walls defining a housing in which the pleated tubing is packed in layered form;

an annular cover extending over said housing; said cover having an inner portion extending downwardly and engaging an upper part of said inner wall of said body and a top portion extending over said housing; said top portion including a tear-off outwardly projecting section having an outer edge engaging an upper part of said outer wall of said annular body; said tear-off section, when torn-off, leaving a peripheral gap to allow access and passage of said tubing therebetween; said downwardly projecting inner portion having an inclined annular area defining a funnel to assist in sliding said tubing when pulled through a central core defined by said inner wall of said body; and … (emphasis added).

(ii) The District Court

Edgewell Personal Care Brands, LLC, and International Refills Company, Ltd. (“Edgewell”) sued Munchkin, Inc. (“Munchkin”) in the United States District Court for the Central District of California (“the district court”) for infringement of claims of the ’420 patent and ’029 patent.

Edgewell manufactures and sells the Diaper Genie, which is a diaper pail system that has two main components: (i) a pail for collection of soiled diapers; and (ii) a replaceable cassette that is placed inside the pail and forms a wrapper around the soiled diapers.

Edgewell accused Second and Third Generation refill cassettes, which Munchkin marketed as being compatible with Edgewell’s Diaper Genie-branded diaper pails.

After the district court issued a claim construction order, construing terms of both the ’420 patent and the ’029 patent, Edgewell continued to assert literal infringement for the ’420 patent, and infringement under the doctrine of equivalents (“the DoE”) for the ’029 patent. Munchkin moved for, and the district court granted, summary judgment of noninfringement of both patents. Edgewell appealed.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit (“the Court”) unanimously vacated the summary judgment of noninfringement (literal infringement) of the ’420 patent, reversed the summary judgment of noninfringement (infringement under the DoE) of the ’029 patent, and remanded the case to the district court for further proceedings.

(i) The ’420 Patent

There was no dispute that the cassette itself contained a clearance when it is not installed in the pail. Rather, the dispute focused on whether the claims required a clearance space between the annular wall defining the chamfer clearance and the pail itself when the cassette was installed (emphasis added). The district court determined that “clearance” required space after cassette installation and construed the clearance as “the space around [interfering] members that remains (if there is any), not the space where the interfering member or cassette is itself located upon insertion” (emphasis added).

The Court held that the district court erred in construing the term “clearance” in a manner dependent on the way the claimed cassette is put to use in an unclaimed structure, and vacated the district court’s grant of summary judgment of noninfringement of the ’420 patent.

On the merits, the Court stated that it is usually improper to construe non-functional claim terms in apparatus claims in a way that makes infringement or validity turn on the way an apparatus is later put to use because an apparatus claim is generally to be construed according to what the apparatus is, not what the apparatus does.

The Court moved on to argue that, absent an express limitation to the contrary, the term “clearance” should be construed as covering all uses of the claimed cassette as the parties do not dispute that the ’420 patent claims are directed only to a cassette. The Court looked into the specification to find that, in nearly all of the disclosed embodiments, the specification suggests that the cassette clearance mates with a complimentary structure in the pail such that there is “engagement” (emphasis added). Thus, the Court concluded that the claim does not require a clearance after insertion. In other words, the specification, taken as a whole, does not support the district court’s construction which would preclude such engagement when the cassette is inserted into the pail (emphasis added).

In conclusion, the Court vacated the district court’s grant of summary judgment of noninfringement of the ’420 patent and remanded the case because the Court held that the district court erred in its construction of the term “clearance.”

(ii) The ’029 Patent

The district court construed “annular cover” in the ’029 patent as “a single, ring-shaped cover, including at least a top portion and an inner portion that are parts of the same structure” (emphasis added). Edgewell did not dispute the construction. Instead, Edgewell sought infringement under the DoE for the ’029 patent because Munchkin’s accused Second and Third Generation cassettes each include a two-part annular cover (emphasis added). The district court granted summary judgment of noninfringement of the ’029 patent under the DoE. because the district court determined that no reasonable jury could find that Munchkin’s Second and Third Generation Cassettes satisfy the ’029 patent’s “annular cover” and “tear-off section” limitations under the DoE given that favorable application of the DoE would effectively vitiate the ‘tear-off section’ limitation (emphasis added).

The Court affirmed the district court’s claim construction in view of the plain language of the claims and the written description of the ’029 patent.

In contrast, the Court disagreed to the district court’s vitiation theory under the DoE. While the Court reconfirmed the vitiation theory by stating that vitiation has its clearest application “where the accused device contain[s] the antithesis of the claimed structure”(citing Planet Bingo, LLC v. GameTech Int’l, Inc., 472 F.3d 1338, 1345 (Fed. Cir. 2006)), the Court cautioned that “[c]ourts should be cautious not to shortcut this inquiry by identifying a ‘binary’ choice in which an element is either present or ‘not present’” (citing Deere & Co. v. Bush Hog, LLC, 703 F.3d 1356–57 (Fed. Cir. 2012)).

Applying these concepts to the facts of this case, the Court conclude that the district court erred in evaluating this element as a binary choice between a single-component structure and a multi-component structure, rather than evaluating the evidence to determine whether a reasonable juror could find that the accused products perform substantially the same function, in substantially the same way, achieving substantially the same result as the claims.

Citing Edgewell’s expert testimony, the Court concluded that the detailed application of the function-way-result test, supported by deposition testimony from Munchkin employees, is sufficient to create a genuine issue of material fact for the jury to resolve and, therefore, is sufficient to preclude summary judgment of noninfringement under the DoE.

In conclusion, the Court reversed the district court’s grant of summary judgment of noninfringement of the ’029 patent under the DoE and remanded the case.

Takeaway

· Claim construction: A term in a claim should be construed as covering all uses of the claimed subject matter.

· Infringement under the DoE: Proof of vitiation requires more than identifying a binary choice in which an element is either “present” or “not present.” Instead, the proof still requires failure of passing the function-way-result test.

Tags: claim construction > doctrine of equivalents > summary judgment > vitiation

When there is competing evidence as to whether a prior art reference is a proper primary reference, an invalidity decision cannot be made as a matter of law at summary judgment

| April 29, 2020

Spigen Korea Co., Ltd. v. Ultraproof, Inc., et al.

April 17, 2020

Newman, Lourie, Reyna (Opinion by Reyna; Dissent by Lourie)

Summary

Spigen Korea Co., Ltd. (“Spigen”) sued Ultraproof, Inc. (“Ultraproof”) for infringement of its multiple patents directed to designs for cellular phone cases. The district court held that as a matter of law, Spigen’s design patents were obvious over prior art references, and granted Ultraproof’s motion for summary judgment of invalidity. However, based on the competing evidence presented by the parties, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the “CAFC”) reversed and remanded, holding that a reasonable factfinder could conclude that a genuine dispute of material fact exists as to whether the primary reference was proper.

原告Spigen社は、自身の所有する複数の携帯電話ケースに関する意匠特許を被告Ultraproof社が侵害しているとして、提訴した。地裁は、原告の意匠特許は、先行技術文献により自明であるとして、裁判官は被告のサマリージャッジメントの申し立てを容認した。しかしながら、連邦控訴巡回裁判所(CAFC)は、双方の提示している証拠には「重要な事実についての真の争い(genuine dispute of material fact)」があるとして、地裁の判決を覆し、事件を差し戻した。

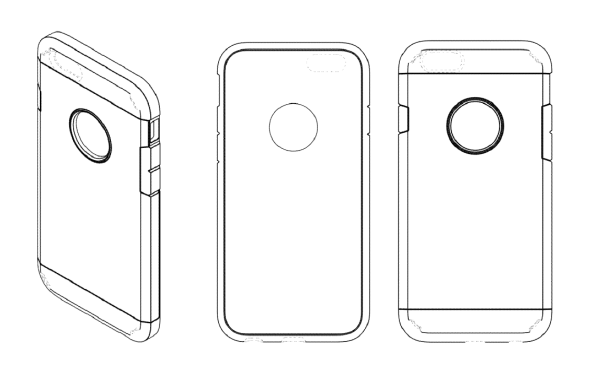

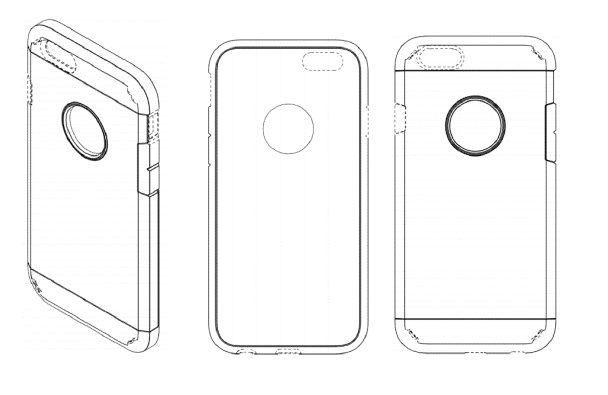

Details

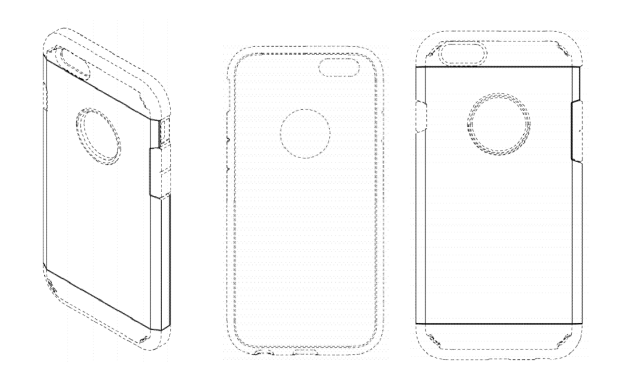

Spigen is the owner of U.S. Design Patent Nos. D771,607 (“the ’607 patent”), D775,620 (“the ’620 patent”), and D776,648 (“the ’648 patent”) (collectively the “Spigen Design Patents”), each of which claims a cellular phone case. Figures 3-5 of the ’607 patent are as shown below:

The ’620 patent disclaims certain elements shown in the ’607 patent, and Figures 3-5 of the ’620 patent are shown below:

Finally, the ’648 patent disclaims most of the elements present in the ’620 patent and the ’607 patent, Figures 3-5 of which are shown below:

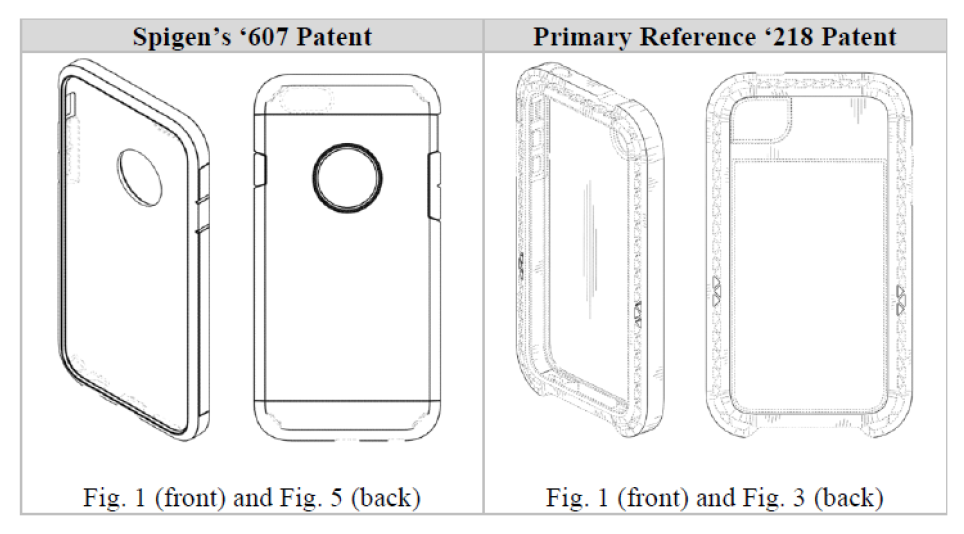

On February 13, 2017, Spigen sued Ultraproof for infringement of Spigen Design Patents in the United States District Court for the Central District of California. Ultraproof filed a motion for summary judgment of invalidity of Spigen Design Patents, arguing that the Spigen Design Patents were obvious as a matter of law in view of a primary reference, U.S. Design Patent No. D729,218 (“the ’218 patent”) and a secondary reference, U.S. Design Patent No. D772,209 (“the ’209 patent”). Spigen opposed the motion arguing that 1) the Spigen Design Patents were not rendered obvious by the primary and secondary reference as a matter of law; and 2) various underlying factual disputes precluded summary judgment. The district court held that as a matter of law, the Spigen Design Patents were obvious over the ’218 patent and the ’209 patent, and granted summary judgment of invalidity in favor of Ultraproof. Ultraproof then moved for attorneys’ fees, which the district court denied. Spigen appealed the district court’s obviousness determination, and Ultraproof cross-appealed the denial of attorneys’ fees.

On appeal, Spigen presented several arguments as to why the district court’s grant of summary judgment should be reversed. First, Spigen argued that there is a material factual dispute over whether the ’218 patent is a proper primary reference that precludes summary judgment. The CAFC agreed. The CAFC explained, citing Titan Tire Corp. v. Case New Holland, Inc., 566 F.3d 1372, 1380-81 (Fed. Cir. 2009) (quoting Durling v. Spectrum Furniture Co., 101 F.3d 100, 103 (Fed. Cir. 1996)) that the ultimate inquiry for obviousness “is whether the claimed design would have been obvious to a designer of ordinary skill who designs articles of the type involved,” which is a question of law based on underlying factual findings. Whether a prior art design qualifies as a “primary reference” is an underlying factual issue. The CAFC went on to explain that a “primary reference” is a single reference that creates “basically the same” visual impression, and for a design to be “basically the same,” the designs at issue cannot have “substantial differences in the[ir] overall visual appearance[s].” Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 678 F.3d 1314, 1330 (Fed. Cir. 2012). A trial court must deny summary judgment if based on the evidence before the court, a reasonable jury could find in favor of the non-moving party. Here, the district court errored in finding that the ’218 patent was “basically the same” as the Spigen Design Patents despite there being “slight differences,” as a reasonable factfinder could find otherwise.

Spigen’s expert testified that the Spigen Design Patents and the ’218 patent are not “at all similar, let alone ‘basically the same.’” Spigen’s expert noted that the ’218 patent has the following features that are different from the Spigen Design Patents:

- unusually broad front and rear chamfers and side surfaces

- substantially wider surface

- lack of any outer shell-like feature or parting lines

- lack of an aperture on its rear side

- presence of small triangular elements illustrated on its chamfers

In contrast, Ultraproof argued that the ’218 patent was “basically the same” because of the presence of the following features:

- a generally rectangular appearance with rounded corners

- a prominent rear chamfer and front chamfer

- elongated buttons corresponding to the location of the buttons of the underlying phone

Ultraproof stated that the only differences were the “circular cutout in the upper third of the back surface and the horizontal parting lines on the back and side surfaces.”

Based on the competing evidence in the record, the CAFC found that a reasonable factfinder could conclude that the ’218 patent and the Spigen Design Patents are not basically the same. T

The CAFC determined that a genuine dispute of material fact exists as to whether the ’218 patent is a proper primary reference, and therefore, reversed the district court’s grant of summary judgment of invalidity and remanded the case for further proceedings.

Takeaway

When there is competing evidence in the record, the determination of whether a prior art reference creates “basically the same” visual impression, and therefore a proper primary reference, is a matter that cannot be decided at summary judgment.

A Patent of Few Words and a Defendant with a Few Parts cannot avoid a Trier of Fact

| February 22, 2019

Centrak, Inc. v. Sonitor Tech., Inc.

February 14, 2019

Before Reyna, Taranto and Chen. Opinion by Chen.

Summary:

The CAFC reversed and remanded a Motion of Summary Judgment finding that the District Court errored in focusing on the length of a written description and dismissing a plausible theory for direct infringement based on the final assembly being done by the defendant within a customer’s system.

Details

- Background

CenTrak, Inc. sued Sonitor Technologies, Inc. for alleged infringement of U.S. Patent No. 8,604,909 (’909 patent), which claims systems for locating and identifying portable devices using ultrasonic base stations. The district court granted Sonitor’s MSJ that the relevant claims are invalid for lack of written description and are not directly infringed because Sonitor does not individually provide for all the aspects of the claims.

The claims are directed to ultrasonic base stations which can be mounted in various fixed locations in a facility, such as rooms in a hospital, and the portable devices can be attached to people or assets that move between rooms. Each portable device is configured to detect the ultrasonic location codes from the nearby ultrasonic base stations and “transmit an output signal including a portable device ID representative of the portable device and the detected ultrasonic location code.” While the portable devices receive location codes from ultrasonic base stations via ultrasound, they might transmit location and device information via RF to an RF base station.

The asserted claims generally recite: (1) ultrasonic (US) base stations; (2) portable devices (tags); (3) a server; (4) radio frequency (RF) base stations; and (5) a backbone network that connects the server with the RF base stations.

All the claims of the ’909 patent are directed to “ultrasonic” components. However, the specification focuses on infrared (IR) or RF components. Only two sentences of the ’909 patent’s specification discuss ultrasonic technology:

Although IR base stations 106 are described, it is contemplated that the base stations 106 may also be configured to transmit a corresponding BS-ID by an ultrasonic signal, such that base stations 106 may represent ultrasonic base stations. Accordingly, portable devices 108 may be configured to include an ultrasonic receiver to receive the BS-ID from an ultrasonic base station.

In regard to lack of written description, Sonitor argued that the two sentences in the specification dedicated to ultrasound, did not show that the inventors had possession of an ultrasound-based RTL system.

Regarding invalidity, the district court ruled that while the specification “contemplated” ultrasound, “[m]ere contemplation . . . is not sufficient to meet the written description requirement.

In regard to infringement, the accused Sonitor Sense system includes three pieces of hardware sold by Sonitor: RF “gateways,” ultrasonic location transmitters, and portable locator tags. Sonitor also provides software for installation on a customer’s server hardware.

Sonitor’s main non-infringement argument was that Sonitor does not make, use, or sell certain elements recited in the claims, including the required backbone network, Wi-Fi access points, or server hardware.

CenTrak argues that the resulting system infringes the ’909 patent when the components Sonitor sells are integrated with a customer’s existing network and server hardware. CenTrak asserted only direct infringement. Since, Sonitor does not sell all of the hardware necessary to practice the asserted claims, so, on appeal, CenTrak only pursued a theory under 35 U.S.C. § 271(a) that Sonitor “makes” infringing systems when it installs and configures the Sonitor Sense system. In short, the crux of CenTrak’s assertion is that there is direct infringement when the party assembles components into the claimed assembly (i.e. the party “makes” the patented invention, even when someone else supplies most of the components).

The district court granted summary judgment of non-infringement. It held that a defendant must be the actor who assembles the entire claimed system to be liable for direct infringement, and CenTrak had not submitted proof that Sonitor personnel had made an infringing assembly.

CenTrak appealed both MSJ grants.

2. Opinion

In regard to invalidity, the CAFC held that, the district court leaned too heavily on the fact that the specification devoted relatively less attention to the ultra-sonic embodiment compared to the infrared embodiment. Quoting their ScriptPro LLC v. Innovation Associates, Inc., 833 F.3d 1336, 1341 (Fed. Cir. 2016), they reiterated that “a specification’s focus on one particular embodiment or purpose cannot limit the described invention where that specification expressly contemplates other embodiments or purposes.”

The Court explained that the real question is the level of detail the ’909 patent’s specification must contain, beyond disclosing that ultrasonic signals can be used, to adequately convey to a skilled artisan that the inventors possessed an ultrasonic embodiment. Citing their Ariad Pharm., Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co., 598 F.3d 1336, 1351 (Fed. Cir. 2010) en banc: “the level of detail required to satisfy the written description requirement varies depending on the nature and scope of the claims and on the complexity and predictability of the relevant technology.” They further noted per Ariad that the issue of whether a claimed invention satisfies the written description requirement is a question of fact.

The opinion details that the parties disputed the complexity and predictability of ultrasonic RTL systems, and the district court erred at the summary judgment stage by not sufficiently crediting testimony from CenTrak’s expert that the differences between IR and ultrasound, when used to transmit small amounts of data over short distances, are incidental to carrying out the claimed invention. The Court specifically noted the testimony from CenTrak’s expert that those details were not particularly complex or unpredictable, and Sonitor does not explain why a person of ordinary skill in the art would need to see such details in the specification to find that the named inventors actually invented the claimed system.

Hence, the Court concluded that:

…there is a material dispute of fact as to whether the named inventors actually possessed an ultrasonic RTL system at the time they filed their patent application or whether they were “leaving it to the . . . industry to complete an unfinished invention.”…

Here, as in ScriptPro, the fact that the bulk of the specification discusses a system with infrared components does not necessarily mean that the inventors did not also constructively reduce to practice a system with ultrasonic components … “the written description requirement does not demand either examples or an actual reduction to practice; a constructive reduction to practice” may be sufficient if it “identifies the claimed invention” and does so “in a definite way.” Ariad, 598 F.3d at 1352.

In regard to direct infringement, the Court noted that it is undisputed that Sonitor does not provide certain claimed elements in the accused systems, such as a backbone network, Wi-Fi access points, or server hardware. Moreover, the district court analyzed the evidence CenTrak offered and concluded that no reasonable jury could find that Sonitor “made” the claimed invention by performing installations relying on Centillion Data Systems, LLC v. Qwest Communications International, Inc., 631 F.3d 1279 (Fed. Cir. 2011) for the proposition that to “make” a system, a single entity must assemble the entire system itself.

The CAFC found that Centillion does not rule out CenTrak’s infringement theory. In this case, Cen-Trak argued that the final, missing elements are the configuration that allows the location transmitters to work with the network and the location codes that are entered into the Sonitor server. According to CenTrak, admissible evidence that Sonitor is the “final assembler” raises a triable issue of fact on infringement even though Sonitor does not “make” each of the claimed components of the accused systems.

The Court further held that under Lifetime Industries, Inc. v. Trim-Lok, Inc., 869 F.3d 1372 (Fed. Cir. 2017), and Cross Med. Prods., Inc. v. Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Inc., 424 F.3d 1293, 1311 (Fed. Cir. 2005), a final assembler can be liable for making an infringing combination—assuming the evidence supports such a finding—even if it does not make each individual component element.

3. Decision

The CAFC found that the District Court errored in both: (1) finding a lack of written description as it relied too heavily on the briefness of the ‘909 patents comments on ultrasonic RTL systems rather than the amount of knowledge needed for a skilled artisan to consider; and (2) finding that there was no dispute of fact as to whether Sonitor was a “final assembler” by virtue of performing the final system installation for its customers. The Court therefore reversed and remanded.

Take away

- The measure of a sufficient written description is not in its length. Rather, the test is to the amount of disclosure necessary for a skilled artisan to discern that the inventor in fact possessed the invention.

- A case for direct infringement can be made even where the defendant does not “make all the parts” if there is sufficient evidence that the accused infringer is a “final assembler” in terms of actuating the combination of elements to infringe.

Tags: 35 U.S.C. §112 > direct infringement > summary judgment > written description

Public use bar inappropriate when participants in clinical trials do not discern specifics of new product

| May 22, 2013

Dey, L.P. v. Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

May 20, 2013

Panel: Bryson, O’Malley, and Newman. Opinion by Bryson. Dissent by Newman.

Summary:

The Federal Circuit reversed and remanded the holding of the District Court that some of Dey’s patents were invalid because a Sunovion’s clinical trial, where Sunovion tested its own product, constituted an invalidating public use. The Federal Circuit determined that although some of test samples were lost and clinical trial was not perfectly confidential, Sunovion’s clinical trial is not an invalidating public use as long as participants do not recognize the specifics of a new drug.

연방지방법원 뉴욕 남부지원(U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York)은 Sunovion의 임상실험 (clinical trial)이 공용 (public use)에 해당된다고 판단하여, Dey의 특허가 무효 (invalid)라도 판결하였다.

이에 불복하여, 원고는 연방항소법원 (U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit)에 상고 (appeal)하였다. 연방항소법원은 임상실험 도중 test sample이 분실되었거나 임상실험이 완벽히 비공개로 진행되지 않았더라도 실험참가자가 신약에 대한 자세한 정보를 모른다면Sunovion의 임상실험은 공용에 해당되지 않는다고 판결하였다.

Tags: anticipation > clinical trial > public use bar > summary judgment > third party use

Means-Plus-Function: The Achilles’ Heel

| May 9, 2012

Noah Systems, Inc. v. Intuit, Inc.

April 9, 2012

Panel: Rader, O’Malley and Reyna. Opinion by Judge O’Malley

Summary

This decision illustrates that a patent could become invalidated even after surviving challenges of reexamination, which strengthen the presumption of validity, when a challenger discovers the Achilles’ Heel of a means-plus-function claim element resulting in a summary judgment of invalidity by the CAFC. Noah appeals the granting, by the United States District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania (DC), of Intuit’s Motion for Summary Judgment of Invalidity of USP 5,875,435 (the ‘435 patent) based on indefiniteness for a means-plus-function claim element without the DC hearing evidence of how one of skill in the art would view the specification. The CAFC affirms by finding that the specification discloses no algorithm when the specification discloses an algorithm that only accomplishes one of two identifiable functions performed by the means-plus-function limitation.