The Federal Circuit declined to be bound by the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance by the Patent Office, but affirmed the Board’s conclusion of the ineligibility, which relied on the Guidance

| May 7, 2020

In re Rudy

April 24, 2020

Prost, Chief Judge, O’Malley and Taranto. Court opinion by Prost.

Summary

The Federal Circuit declined to be bound by the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance by the Patent Office, and instead followed the Supreme Court’s Alice/Mayo framework, and the Federal Circuit’s interpretation and application thereof. However, the Federal Circuit unanimously affirmed the Board’ affirmance of the Examiner’s rejection of claims 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, and 45–49 of the ’360 application as patent-ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101, which was fully relied on the Office Guidance.

Details

I. background

United States Patent Application No. 07/425,360 (“the ’360 application”), filed by Christopher Rudy on October 21, 1989 (before the signing of the 1994 Uruguay Round Agreements Act), is entitled “Eyeless, Knotless, Colorable and/or Translucent/Transparent Fishing Hooks with Associatable Apparatus and Methods.” After a lengthy prosecution of more than twenty years, including numerous amendments and petitions, four Board appeals, and a previous trip to the Federal Circuit where the obviousness of all claims then on appeal was affirmed (In re Rudy, 558 F. App’x. 1011 (Fed. Cir. 2014) (non-precedential)), claim 34, which the Board considered illustrative, reads as follows:

34. A method for fishing comprising steps of

(1) observing clarity of water to be fished to deter- mine whether the water is clear, stained, or muddy,

(2) measuring light transmittance at a depth in the water where a fishing hook is to be placed, and then

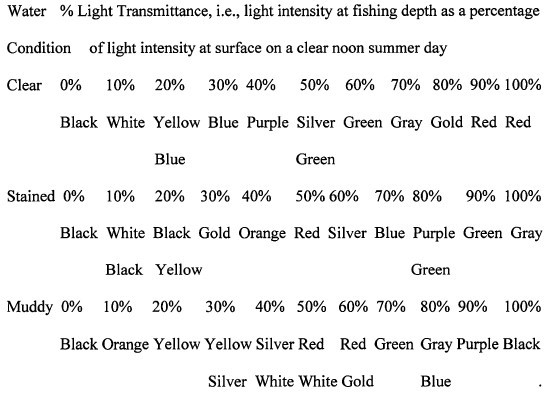

(3) selecting a colored or colorless quality of the fishing hook to be used by matching the observed water conditions ((1) and (2)) with a color or colorless quality which has been previously determined to be less attractive under said conditions than has undergone those pointed out by the following correlation for fish-attractive non-fluorescent colors:

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) affirmed the Examiner’s rejection of claims 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, and 45–49 of the ’360 application in the last Board appeal. The Board conducted its analysis under a dual framework for patent eligibility, purporting to apply both 1) “the two-step framework described in Mayo [Collaborative Ser- vices v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 566 U.S. 66 (2012)] and Alice [Corp. v. CLS Bank International, 573 U.S. 208 (2014)],” and 2) the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance, 84 Fed. Reg. 50 (Jan. 7, 2019) (“Office Guidance”), published by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“Patent Office”). Specifically, the Board concluded “[u]nder the first step of the Alice/Mayo framework and Step 2A, Prong 1, of [the] Office Guidelines” that claim 34 is directed to the abstract idea of “select[ing] a colored or colorless quality of a fishing hook based on observed and measured water conditions, which is a concept performed in the human mind.” The Board went on to conclude that “[u]nder the second step in the Alice/Mayo framework, and Step 2B of the 2019 Revised Guidance, we determine that the claim limitations, taken individually or as an ordered combination, do not amount to significantly more than” the abstract idea.

Mr. Rudy timely appealed, challenging both the Board’s reliance on the Office Guidance, and the Board’s ultimate conclusion that the claims are not patent eligible.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit unanimously affirmed the Board’ affirmance of the Examiner’s rejection of claims 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, and 45–49 of the ’360 application.

1. Office Guidance vs. Case Law

Mr. Rudy contended that the Board “misapplied or refused to apply . . . case law” in its subject matter eligibility analysis and committed legal error by instead applying the Office Guidance “as if it were prevailing law.”

The Federal Circuit agreed with Mr. Rudy, stating: “[w]e are not[] bound by the Office Guidance, which cannot modify or supplant the Supreme Court’s law regarding patent eligibility, or our interpretation and application thereof.” Interestingly, the Federal cited a non-precedential opinion to support its position: “As we have previously explained:

While we greatly respect the PTO’s expertise on all matters relating to patentability, including patent eligibility, we are not bound by its guidance. And, especially regarding the issue of patent eligibility and the efforts of the courts to determine the distinction between claims directed to [judicial exceptions] and those directed to patent-eligible ap- plications of those [exceptions], we are mindful of the need for consistent application of our case law.

Cleveland Clinic Found. v. True Health Diagnostics LLC, 760 F. App’x. 1013, 1020 (Fed. Cir. 2019) (non-precedential). ”

In conclusion, the Federal Circuit declared: “[t]o the extent the Office Guidance contradicts or does not fully accord with our caselaw, it is our caselaw, and the Supreme Court precedent it is based upon, that must control.”

2. Subject Matter Eligibility of Rudy’s Case

The Federal Circuit concluded that although a portion of the Board’s analysis is framed as a recitation of the Office Guidance, the Board’s reasoning and conclusion for Rudy’s case are nevertheless fully in accord with the relevant caselaw in this particular case.

To determine whether a patent claim is ineligible subject matter, the U.S. Supreme Court has established a two-step Alice/Mayo framework. In Step One, courts must determine whether the claims at issue are directed to a patent-ineligible concept such as an abstract idea. Alice, 573 U.S. at 208. In Step Two, if the claims are directed to an abstract idea, the courts must “consider the elements of each claim both individually and ‘as an ordered combination’ to determine whether the additional elements ‘transform the nature of the claim’ into a patent-eligible application.” Id. To transform an abstract idea into a patent-eligible application, the claims must do “more than simply stat[e] the abstract idea while adding the words ‘apply it.’” Id. at 221. At each step, the claims are considered as a whole. See id. at 218 n.3, 225.

a. Step One

With respect to claim 34, the Federal Circuit concluded, as the Board did, that the claim is directed to the abstract idea of selecting a fishing hook based on observed water conditions. Specifically, the Federal Circuit compared claim 34 with Elec. Power Grp., and reasoned that claim 34 requires nothing more than collecting information (water clarity and light transmittance) and analyzing that information (by applying the chart included in the claim), which collectively amount to the abstract idea of selecting a fishing hook based on the observed water conditions. See Elec. Power Grp., LLC v. Alstom S.A., 830 F.3d 1350, 1353–54 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (the Federal Circuit held in the computer context that “collecting information” and “analyzing” that information are within the realm of abstract ideas.).

The Federal Circuit disagreed with Mr. Rudy’s contention that claim 34’s preamble, “a method for fishing,” is a substantive claim limitation such that each claim requires actually attempting to catch a fish by placing the selected fishing hook in the water. The Federal Circuit reasoned that such an “additional limitation,” even if that were true, would not alter the conclusion because the character of claim 34 as a whole remains directed to an abstract idea.

The Federal Circuit also disagreed with Mr. Rudy’s contention that claim 34 is not directed to an abstract idea both because fishing “is a practical technological field . . . recognized by the PTO” and because he contends that observing light transmittance is unlikely to be performed mentally. Regarding the “practical technological field,” the Court reasoned that the undisputed fact that an applicant can obtain subject-matter eligible claims in the field of fishing is irrelevant to the fact that the claims currently before the Court are not eligible. Regarding the unlikeliness of the mental performance, the Court pointed our that the plain language of the claims encompasses such mental determination.

The Federal Circuit further rejected Mr. Rudy’s contention that, relying on the machine-or-transformation test, practicing claim 34 “acts upon or transforms fish” by transforming “freely swimming fish to hooked and landed fish” or by transforming a fishing hook “from one not having a target fish on it to one dressed with a fish when a successful strike ensues.” The Court declined to decide in this case whether the transformation from free fish to hooked fish is the type of transformation discussed in Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593, 604 (2010) and its predecessor cases. Instead, the Court stated that claim 34 does not actually recite or require the purported transformation that Mr. Rudy relies upon because, as Mr. Rudy’s explained, “landing a fish is never a sure thing. Many an angler has gone fishing and returned empty handed.”

b. Step Two

In the Step Two Analysis, the Court concluded that claim 34 fails to recite an inventive concept at step two of the Alice/Mayo test, and is thus not patent eligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101 because the three elements of the claim (observing water clarity, measuring light transmittance, and selecting the color of the hook to be used), either individually or as an ordered combination, do not amount to “‘significantly more than a patent upon the ineligible concept itself.’” The argument in the Step Two Analysis appears somewhat cursory.

c. The Remaining Claims

The Federal Circuit concluded that claim 38, the only other independent claim on appeal, is not patent-eligible as well.

Claim 38 begins with a method that is substantively identical to claim 34, but includes a slightly different chart for selecting the fishing hook color, and further includes only one additional limitation, which recites: “wherein the fishing hook used is disintegrated from but is otherwise connectable to a fishing lure or other tackle and has a shaft portion, a bend portion connected to the shaft portion, and a barb or point at the terminus of the bend, and wherein the fishing hook used is made of a suitable material, which permits transmittance of light therethrough and is colored to colorless in nature.”

The Court stated that the slightly different substance of claim 38’s chart does not render it patent eligible because the substance of claim 34’s hook color chart was not the basis of the eligibility determination. The Court further stated that its step-one analysis of claim 34 is equally applicable to claim 38 because, as described above, this limitation does not change the fact that the character of the claim, as a whole, is directed to an abstract idea.

The Court also affirmed the Board’s conclusions that dependent claims 35, 37, and 40 are not patent eligible, as each recites the physical attributes of the connection between the fishing hook and the fishing lure in ways not meaningfully distinct from claim 38.

The Court further affirm the Board’s conclusions regarding claims 45–49, which differ from the previously discussed claims only in that they mandate a specific color of fishing hook, which neither changes the character of the claims as a whole, nor provides an inventive concept distinct from the abstract idea itself.

Takeaway

· The case demonstrates that courts still stick to the comparative approach in Alice step one, instead of defining or categorizing the “abstract idea.” This approach is notably in contrast with that of the Patent Office, which follows the Office Guidance, dividing Alice step one into two inquiries: (i) evaluate whether the claim recites a judicial exception; and (ii) evaluate whether the judicial exception is integrated into a practical application if the claim recites a judicial exception.

· To be on the safe side for the purpose of drafting a patent specification including claim(s), which is robust to an invalidity defense under 35 U.S.C. § 101, the Supreme Court’s law regarding patent eligibility, and the Federal Circuit’s interpretation and application thereof, not the Office Guidance, shall be relied on.

Arguments of “as a whole”, “high level of abstraction,” “novelty/nonobviousness,” “physicality” and “machine-or-transformation test” for subject matter eligibility were successful at the PTAB and the district court, but not at the Federal Circuit

| August 30, 2019

Solutran, Inc. v. Elavon, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2019) (Case Nos. 2019-1345, 2019-1460)

July 30, 2019

Chen, Hughes, and Stoll, Circuit Judges. Court opinion by Chen.

Summary

The Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s denial of summary judgment of ineligibility regarding a patented claims titled “system and method for processing checks and check transactions,” by concluding that the asserted claims are not directed to patent-eligible subject matter under § 101 because, under the Alice two-step framework, the claims recited the abstract idea of using data from a check to credit a merchant’s account before scanning the check, and because the claims do not contain an inventive concept sufficient to transform this abstract idea into a patent-eligible application.

Details

I. background

1. The Patent

Solutran, Inc. (Solutran) owns U.S. Patent No. 8,311,945 (’945 patent), titled “System and method for processing checks and check transactions.” The proffered benefits include “improved funds availability” for merchants and allegedly “reliev[ing merchants] of the task, cost, and risk of scanning and destroying the paper checks themselves, relying instead on a secure, high-volume scanning operation to obtain digital images of the checks.” ’945 patent at col. 3, ll. 46–62.

Claim 1, the representative claim of the ’945 patent, recites as follows:

1. A method for processing paper checks, comprising:

a) electronically receiving a data file containing data captured at a merchant’s point of purchase, said data including an amount of a transaction associated with MICR [(Magnetic Ink Character Recognition)] information for each paper check, and said data file not including images of said checks;

b) after step a), crediting an account for the merchant;

c) after step b), receiving said paper checks and scanning said checks with a digital image scanner thereby creating digital images of said checks and, for each said check, associating said digital image with said check’s MICR information; and

d) comparing by a computer said digital images, with said data in the data file to find matches.

2. The Alice Two-Step Framework under 35 U.S.C. § 101

To determine whether a patent claims ineligible subject matter, the U.S. Supreme Court has established a two-step framework. In Step One, courts must determine whether the claims at issue are directed to a patent-ineligible concept such as an abstract idea. Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank International, 573 U.S. 208, 217 (2014). In Step Two, if the claims are directed to an abstract idea, the courts must “consider the elements of each claim both individually and ‘as an ordered combination’ to determine whether the additional elements ‘transform the nature of the claim’ into a patent-eligible application.” Id. To transform an abstract idea into a patent-eligible application, the claims must do “more than simply stat[e] the abstract idea while adding the words ‘apply it.’” Id. at 221. At each step, the claims are considered as a whole. See id. at 218 n.3, 225.

3. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB)

Two months after the Supreme Court issued the decision in Alice, the PTAB issued an institution decision granting a petition of a covered business method (CBM) review by U.S. Bancorp as to the § 103 challenge (obviousness) but denying a petition as to the § 101 challenge (lack of subject matter eligibility), concluding that claim 1 of the ’945 patent was not directed to an abstract idea. U.S. Bancorp v. Solutran, Inc., No. CBM2014-00076, 2014 WL 3943913 (P.T.A.B. Aug. 7, 2014). The PTAB reasoned that “the basic, core concept of independent claim 1 is a method of processing paper checks, which is more akin to a physical process than an abstract idea.” Id. at *8. It is noted that the CBM post-grant review certificate was issued under 35 U.S.C. § 328(b) on February 14, 2018, reflecting the final results of CBM2014-00076 determining that claims 1-6 are found patentable.

3. The District Court

Solutran sued U.S. Bancorp and its affiliate Elavon, Inc. (collectively, U.S. Bank) in the United States District Court for the District of Minnesota, alleging infringement of claims 1-5 of the ’945 patent. U.S. Bank moved for summary judgment that the ’945 patent was invalid because the claims were directed to the “abstract idea of delaying and outsourcing the scanning of paper checks.”

On February 23, 2018, the district court entered summary judgment for Solutran finding that the ‘945 patent was patent eligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101 for following reasons:

· Step One: The district court found the previous CBM review of the ’945 patent by the PTAB persuasive, concluding that that the ’945 patent is directed to an improved technique for processing and transporting physical checks, rather than just handling data that had been scanned from the checks.

· Step Two: The district court concluded, in the alternative, that the asserted claims also recited an inventive concept under step two of Alice. The district court accepted Solutran’s assertion that “Claim 1’s elements describe a new combination of steps, in an ordered sequence, that was never found before in the prior art and has been found to be a nonobvious improvement over the prior art by both the USPTO examiner and the PTAB’s three-judge panel.” The district court also concluded that the claim passes the machine-or-transformation test because “the physical paper check is transformed into a different state or thing, namely into a digital image.”

U.S. Bank appeals, inter alia, the § 101 ruling. Solutran cross-appeals on the issue of willful infringement.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit reversed the summary judgment in favor of Solutran on the issue of the subject matter eligibility, concluding that, contrary to the views of the PTAB and the district court, the claims are not directed to patent-eligible subject matter under § 101 because the claims of the ’945 patent recite the abstract idea of using data from a check to credit a merchant’s account before scanning the check, and because the claims do not contain an inventive concept sufficient to transform this abstract idea into a patent-eligible application. The Federal Circuit thus did not review U.S. Bank’s alternative § 103 argument or Solutran’s cross-appeal relating to a potential willful infringement claim.

The unanimous court opinion by Circuit Judge Chen discussed each step of the two-step framework in detail.

1. Step One

The Federal Circuit concluded that the claims are directed to the abstract idea of crediting a merchant’s account as early as possible while electronically processing a check.

Comparison with Precedents

The Federal Circuit has a precedent as to the determination of “abstract idea” that the court finds it sufficient to compare claims at issue to those claims already found to be directed to an abstract idea in previous cases, instead of establishing a definitive rule to determine what constitutes an “abstract idea.” Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., 822 F.3d 1327, 1334 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

The court opinion argued that “[a]side from the timing of the account crediting step, the ’945 patent claims recite elements similar to those in Content Extraction & Transmission LLC v. Wells Fargo Bank, National Ass’n, 776 F.3d 1343 (Fed. Cir. 2014)” where the Federal Circuit held that a method of extracting and then processing information from hard copy documents, including paper checks, was drawn to the abstract idea of collecting data, recognizing certain data within the collected data set, and storing that recognized data in a memory. As for the account crediting step, the court opinion stated that “[c]rediting a merchant’s account as early as possible while electronically processing a check is a concept similar to those determined to be abstract by the Supreme Court in Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593 (2010) and Alice.”

In sum, the court opinion concluded that the claims at issue are similar to those claims already found to be directed to an abstract idea in previous cases.

As A Whole

Solutran argued that the claims “as a whole” are not directed to an abstract idea. The court opinion countered by pointing out that “[t]he only advance recited in the asserted claims is crediting the merchant’s account before the paper check is scanned,” and concluded that this is an abstract idea.

The court opinion distinguished this case from previous cases where claims were held patent-eligible by noting that this is not “a situation where the claims “are directed to a specific improvement to the way computers operate” and therefore not directed to an abstract idea, as in cases such as Enfish,” nor is it “a situation where the claims are “limited to rules with specific characteristics” to create a technical effect and therefore not directed to an abstract idea, as in McRO, Inc. v. Bandai Namco Games America Inc., 837 F.3d 1299, 1313 (Fed. Cir. 2016).” The court opinion further stated that “[t]o the contrary, the claims are written at a distinctly high level of generality.”

High Level of Abstraction

The court opinion disagreed with Solutran that U.S. Bank “improperly construe[d] Claim 1 to ‘a high level of abstraction.’” While conceding that “all inventions at some level embody, use, reflect, rest upon, or apply laws of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract ideas,” Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., Inc., 566 U.S. 66, 70, 71 (2012), the court opinion stressed “where, as here, the abstract idea tracks the claim language and accurately captures what the patent asserts to be the “focus of the claimed advance over the prior art,” Affinity Labs of Texas, LLC v. DIRECTV, LLC, 838 F.3d 1253, 1257 (Fed. Cir. 2016), characterizing the claim as being directed to an abstract idea is appropriate.”

Physicality of The Paper Checks Being Processed and Transported

The court opinion concluded that “the physicality of the paper checks being processed and transported is not by itself enough to exempt the claims from being directed to an abstract idea” by citing a precedent that “the abstract idea exception does not turn solely on whether the claimed invention comprises physical versus mental steps,” In re Marco Guldenaar Holding B.V., 911 F.3d 1157, 1161 (Fed. Cir. 2018),

2. Step Two

The court opinion disagreed with the district court’s holding that the ’945 patent claims “contain a sufficiently transformative inventive concept so as to be patent eligible.”

As A Whole

The court opinion stated that “[e]ven when viewed as a whole, these claims “do not, for example, purport to improve the functioning of the computer itself” or “effect an improvement in any other technology or technical field” and that “[t]o the contrary, as the claims in [Ultramercial, Inc. v. Hulu, LLC, 772 F.3d 709 (Fed. Cir. 2014)] did, the claims of the ’945 patent “simply instruct the practitioner to implement the abstract idea with routine, conventional activity.”” The court opinion further found any remaining elements in the claims, including use of a scanner and computer and “routine data-gathering steps” (i.e., receipt of the data file), as “hav[ing] been deemed insufficient by this court in the past to constitute an inventive concept” in the past precedents. Content Extraction, 776 F.3d at 1349 (conventional use of computers and scanners); OIP Techs., Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc., 788 F.3d 1359, 1363 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (routine data- gathering steps).

Novelty/Nonobviousness

In rejecting Solutran’s argument that these claims are patent-eligible because they are allegedly novel and nonobvious, the court opinion reiterated the precedent that “merely reciting an abstract idea by itself in a claim—even if the idea is novel and non-obvious—is not enough to save it from ineligibility.” See, e.g., Synopsys, Inc. v. Mentor Graphics Corp., 839 F.3d 1138, 1151 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (“[A] claim for a new abstract idea is still an abstract idea.” (emphasis in original)).”

Machine-or-Transformation Test

In rejecting Solutran’s argument that its claims passed the machine-or-transformation test—i.e., “transformation and reduction of an article ‘to a different state or thing,’” the court opinion stated “[w]hile the Supreme Court has explained that the machine-or-trans- formation test can provide a “useful clue” in the second step of Alice, passing the test alone is insufficient to overcome Solutran’s above-described failings under step two. See DDR Holdings, LLC v. Hotels.com, L.P., 773 F.3d 1245, 1256 (Fed. Cir. 2014) (“[I]n Mayo, the Supreme Court emphasized that satisfying the machine-or-transformation test, by itself, is not sufficient to render a claim patent-eligible, as not all transformations or machine implementations infuse an otherwise ineligible claim with an ‘inventive concept.’”).”

Takeaway

· The case demonstrates that courts still stick to the comparative approach in Alice step one, instead of defining or categorizing the “abstract idea.” This approach is notably in contrast with that of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, which follows the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance on January 7, 2019, dividing Alice step one into two inquiries: (i) evaluate whether the claim recites a judicial exception; and (ii) evaluate whether the judicial exception is integrated into a practical application if the claim recites a judicial exception. The courts’ approach may give wider latitude to turn an issue of the subject matter eligibility in either direction for its less clarity of the standard.

· Physicality of subjects recited in a claim, novelty/nonobviousness of the claim, and passing of the machine-or-transformation test may not be enough to exempt the claim from being directed to an abstract idea.

Plausible and specific factual allegations of inventive claims are enough to survive a motion to dismiss for Patent Ineligible Subject Matter

| July 22, 2019

Cellspin Soft, Inc. v. Fitbit, Inc.

June 25, 2019

Lourie, O’Malley, and Taranto

Summary:

Cellspin sued Fitbit and nine other defendants for infringement of various claims of four different patents relating to connecting a data capture device such as a digital camera to a mobile device. Fitbit filed a motion to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(6) because the asserted claims of all of the patents are to patent ineligible subject matter under § 101. The district court granted the motion to dismiss and Cellspin appealed to the CAFC. The CAFC agreed with the district court that the claims recite an abstract idea under step one of the Alice test. However, under step two of the Alice test, the CAFC stated that Cellspin made “specific, plausible factual allegations about why aspects of its claimed inventions were not conventional,” and that “the district court erred by not accepting those allegations as true.” Thus, the CAFC vacated the district court decision and remanded.

Details:

Cellspin sued Fitbit and nine other defendants for infringement of several claims of four different patents. The four patents are U.S. Patent Nos. 8,738,794; 8,892,752; 9,258,698; and 9,749,847. These patents share the same specification and relate to connecting a data capture device such as a digital camera, to a mobile device so that a user can automatically publish content from the data capture device to a website.

According to the ‘794 patent, prior art devices had to transfer their content from the digital capture device to a personal computer using a memory stick or cable. The ‘794 patent teaches using a short-range wireless communication protocol such as bluetooth to automatically or with minimal user intervention transfer and upload data from a data capture device to a mobile device. The mobile device can then automatically or with minimal user intervention publish the content on websites.

Claim 1 of the ‘794 patent recites:

1. A method for acquiring and transferring data from a Bluetooth enabled data capture device to one or more web services via a Bluetooth enabled mobile device, the method comprising:

providing a software module on the Bluetooth enabled data capture device;

providing a software module on the Bluetooth enabled mobile device;

establishing a paired connection between the Bluetooth enabled data capture device and the Bluetooth enabled mobile device;

acquiring new data in the Bluetooth enabled data capture device, wherein new data is data acquired after the paired connection is established;

detecting and signaling the new data for transfer to the Bluetooth enabled mobile device, wherein detecting and signaling the new data for transfer comprises:

determining the existence of new data for transfer, by the software module on the Bluetooth enabled data capture device; and

sending a data signal to the Bluetooth enabled mobile device, corresponding to existence of new data, by the software module on the Bluetooth enabled data capture device automatically, over the established paired Bluetooth connection, wherein the software module on the Bluetooth enabled mobile device listens for the data signal sent from the Bluetooth enabled data capture device, wherein if permitted by the software module on the Bluetooth enabled data capture device, the data signal sent to the Bluetooth enabled mobile device comprises a data signal and one or more portions of the new data;

transferring the new data from the Bluetooth enabled data capture device to the Bluetooth enabled mobile device automatically over the paired Bluetooth connection by the software module on the Bluetooth enabled data capture device;

receiving, at the Bluetooth enabled mobile device, the new data from the Bluetooth enabled data capture device;

applying, using the software module on the Bluetooth enabled mobile device, a user identifier to the new data for each destination web service, wherein each user identifier uniquely identifies a particular user of the web service;

transferring the new data received by the Bluetooth enabled mobile device along with a user identifier to the one or more web services, using the software module on the Bluetooth enabled mobile device;

receiving, at the one or more web services, the new data and user identifier from the Bluetooth enabled mobile device, wherein the one or more web services receive the transferred new data corresponding to a user identifier; and

making available, at the one or more web services, the new data received from the Bluetooth enabled mobile device for public or private consumption over the internet, wherein one or more portions of the new data correspond to a particular user identifier.

The opinion highlighted as relevant that claim 1 requires establishing a paired connection between the data capture device and the mobile device before data is transmitted between the two. The other claims from the other patents recite small variations of claim 1 of the ‘794 patent.

Nine defendants filed a motion to dismiss under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) and one defendant filed a motion to dismiss under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(c). The motions argued that the asserted patents are ineligible under § 101. The district court granted the motions to dismiss stating that all of the asserted claims from all of the asserted patents are to ineligible subject matter under § 101.

CAFC – Step One Analysis

Cellspin argued that the claims are directed to improving internet-capable data capture devices and mobile networks and that its claims recite technological improvements because the claims describe improving data capture devices by allowing even “internet-incapable” capture devices to transfer newly captured data to the internet via an internet capable mobile device.

The CAFC characterized the claims as “drawn to the idea of capturing and transmitting data from one device to another.” And the CAFC stated that they have “consistently held that similar claims reciting the collection, transfer, and publishing of data are directed to an abstract idea,” and that these cases “compel the conclusion that the asserted claims are directed to an abstract idea as well.” The CAFC further stated that the patents acknowledge that users could already transfer data from a data capture device (even an internet-incapable device) to a website using a cable connected to a PC, and that the patents provided a way to automate this transfer. Thus, the CAFC concluded that the district court correctly held that the asserted claims are to an abstract idea.

CAFC – Step Two Analysis

Cellspin argued that the claimed invention was unconventional. They described the prior art devices as including a capture device with built-in wireless internet, but that these devices were inferior because at the time of the patent priority date, these combined devices were bulky, expensive in terms of hardware and expensive in terms of requiring an extra or separate cellular service for the data capture device. Cellspin stated that its device was unconventional in that it separated the steps of capturing and publishing the data by separate devices linked by a wireless, paired connection. This invention allowed for the data capture device to serve one core function of capturing data without the need to incorporate other hardware and software components for storing data and publishing on the internet. And one mobile device with one data plan can be used to control several data capture devices.

Cellspin further argued that its specific ordered combination of elements was inventive because Cellspin’s claimed device requires establishing a paired connection between the mobile device and the data capture device before data is transmitted, whereas the prior art data capture device forwarded data to a mobile device as captured regardless of whether the mobile device is capable of receiving the data, i.e. whether the mobile device is on and whether the mobile device is near the data capture device. Cellspin also argued that its use of HTTP transfers of data received over a paired connection to web services was non-existent prior to its invention.

The district court stated that Cellspin failed to cite support in the patent specifications for its allegations regarding the inventive concepts and benefits of its invention. However, the CAFC stated that in the Aatrix case (Aatrix Software Inc. v. Green Shades Software, Inc., 882 F.3d 1121 (Fed. Cir. 2018)), they repeatedly cited allegations in the complaint to conclude that the disputed claims were potentially inventive. The CAFC stated:

While we do not read Aatrix to say that any allegation about inventiveness, wholly divorced from the claims or the specification, defeats a motion to dismiss, plausible and specific factual allegations that aspects of the claims are inventive are sufficient. Id. As long as what makes the claims inventive is recited by the claims, the specification need not expressly list all the reasons why this claimed structure is unconventional.

The CAFC stated that in this case, Cellspin made “specific, plausible factual allegations about why aspects of its claimed inventions were not conventional,” and that “the district court erred by not accepting those allegations as true.”

The district court also did not give weight to Cellspins’ allegations because Cellspin relied on Berkheimer (Berkheimer v. HP Inc., 881 F.3d 1360 (Fed. Cir. 2018)), which was distinguished by the district court because the Berkheimer case dealt with a motion for summary judgment. But the CAFC stated that the district court’s conclusion cannot be reconciled with the Aatrix case and stated:

The district court thus further erred by ignoring the principle, implicit in Berkheimer and explicit in Aatrix, that factual disputes about whether an aspect of the claims is inventive may preclude dismissal at the pleadings stage under § 101.

The CAFC further stated that Cellspin did more than just label certain techniques as inventive; Cellspin pointed to evidence suggesting that these techniques had not been implemented in the same way. The CAFC concluded that Cellspin sufficiently alleged that they claimed significantly more than the idea of capturing, transferring or publishing data, and thus the district court erred by granting the motion to dismiss.

Attorney Fees

The CAFC also commented on the district court’s decision to award attorney fees to the defendant. The district court awarded attorney fees to the defendants because the district court deemed the case exceptional due to actions by Cellspin. But since the CAFC found that the district court erred in granting the motions to dismiss, the CAFC vacated the award of attorney fees. But the CAFC went further to point out errors by the district court in determining the case to be exceptional.

The CAFC faulted the district court for not presuming that the issued patents are eligible. The CAFC stated that issued patents are not only presumed to be valid but also presumed to be patent eligible. In citing Berkheimer, the CAFC stated that underlying facts regarding whether a claim element or combination is well-understood or routine must be proven by clear and convincing evidence.

Comments

A patent owner as a plaintiff in an infringement suit can defend against a motion to dismiss by providing “specific, plausible factual allegations” about why aspects of the claimed invention were not conventional. Explicit description in the specification providing reasons why the claimed invention is unconventional is not required as long as the claim recites what makes the claim inventive. Also, this case states that underlying facts regarding ineligibility must be proven by clear and convincing evidence.

Even though this case states that explicit description in the specification regarding why the invention is unconventional is not required, patent applicants should consider including a description in the specification regarding why the invention or certain aspects of the invention are unconventional to make their patents stronger.

Spreadsheet Tabs Survive Alice Test of Patent Subject Matter Eligibility

| November 2, 2018

Data Engine Technologies LLC v. Google LLC

October 9, 2018

Before Reyna, Bryson, Stoll. Opinion by Stoll.

Summary:

This case is about patent claims to spreadsheet functionality. On an appeal from a grant of a motion for judgement on the pleadings for lack of patent-eligible subject matter, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit reversed-in-part finding some of the claims patent eligible. Specifically, the claims reciting a “spreadsheet page identifier being displayed as an image of a notebook tab” were held as not being directed to an abstract idea. However, claims that more generally recite identifying and storing electronic spreadsheet pages and claims that recite methods that allow electronic spreadsheet users to track their changes were held as invalid under § 101 because they fail step one of Alice as being abstract, and they fail step two of Alice because they merely recite the method of implementing the abstract idea itself.