Why not to be conclusory!

| September 6, 2023

Volvo Penta of the Ams. LLC v. Brunswick Corp.

Decided: August 24, 2023

Before Moore, Chief Judge, Lourie and Cunningham, Circuit Judges. Authored by Chief Judge, Lourie.

Summary:

The CAFC vacated a Final Written Decision of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) holding all claims of U.S. Patent 9,630,692 (the “’962 patent”), owned by Volvo Penta, unpatentable as obvious. The court remanded the decision for further evaluation of objective indicia of non-obviousness that the Board had not adequately considered.

- A steerable tractor-type drive for a boat, comprising:

a drive support mountable to a stern of the boat;

a drive housing pivotally attached to the support about a steering axis, the drive housing having a vertical drive shaft connected to drive a propeller shaft, the propeller shaft extending from a forward end of the drive housing;

at least one pulling propeller mounted to the propeller shaft,

wherein the steering axis is offset forward of the vertical drive shaft.

The ’962 patent is directed to a boat drive, designed to provide a “pulling-type” or “forward facing drive” positioned under the stern of the boat. Claim 1 of the ’692 patent, reproduced below, is representative.

In 2015, Volvo Penta launched its commercial embodiment of the ’692 patent, the ‘Forward Drive.’ This product became extremely successful once available, particularly for wakesurfing and other water sports.

In August 2020, Brunswick Corp. (“Brunswick”) launched its own drive that also embodied the ’692 patent, the ‘Bravo Four S.’ The same day that Brunswick launched the Bravo Four S, it petitioned for inter partes review of all claims of the ’692 patent. Relevant to this appeal, Brunswick asserted that the challenged claims would have been obvious based on the references, Kiekhaefer and Brandt. Kiekhaefer is a 1952 patent assigned to Brunswick and directed to an outboard motor that could have either rear-facing or forward-facing propellers. Brandt is a 1989 patent assigned to Volvo Penta and directed to a stern drive with rear-facing propellers.

Volvo Penta position was not that the references combined failed to disclose all the claim elements, but rather that there was a lack of motivation to combine said references. Volvo Penta further proffered evidence of six objective indicia of non-obviousness: copying, industry praise, commercial success, skepticism, failure of others, and long-felt but unsolved need.

Ultimately, the Board had found Volvo Penta’s position unpersuasive asserting that sufficient motivation was found and that Volvo Penta’s objective evidence of secondary considerations was insufficient to outweigh Brunswick’s “strong evidence of obviousness.”

Accordingly, Volvo Penta raises three main arguments on appeal: (1) that the Board’s finding of motivation to combine was not supported by substantial evidence, (2) that the Board erred in its determination that there was no nexus, and (3) that the Board erred in its consideration of Volvo Penta’s objective evidence of secondary considerations of nonobviousness.

The court discussed each one in turn:

- Motivation:

The court began:

The ultimate conclusion of obviousness is a legal determination based on underlying factual findings, including whether or not a relevant artisan would have had a motivation to combine references in the way required to achieve the claimed invention. Henny Penny Corp. v. Frymaster LLC, 938 F.3d 1324, 1331 (Fed. Cir. 2019) (citing Wyers v. Master Lock Co., 616 F.3d 1231, 1238–39 (Fed. Cir. 2010)).

Volvo Penta first argued that the Board ignored a number of assertions in its favor, including: (1) that Brunswick, despite having knowledge of Kiekhaefer for decades, never attempted the proposed modification itself; (2) that Brunswick’s proposed modification would have entailed a nearly total and exceedingly complex redesign of the drive system; (3) the complexity of and difficulty in shifting the vertical drive shaft of Kiekhaefer; and (4) that Brunswick itself attempted to make its proposed modification yet failed to create a functional drive. The court disagreed on all points.

The Board acknowledged the testimony of Volvo Penta’s expert that a “complete redesign of Brandt” would be necessary, including “over two dozen modifications,” but ultimately found that not all of the identified changes would have been required to arrive at the claimed invention.

Volvo Penta also argued that the Board’s reliance on Kiekhaefer for motivation to combine was misplaced. The Board had relied on Kiekhaefer teaching that a “tractor-type propeller” is “more efficient and capable of higher speeds.” Volvo Penta argued this is not the metric by which recreational boats are measured.

However, again, the court disagreed stating that while ‘it is likewise not conclusive that speed may not be the primary or only metric by which recreational boats are measured. Substantial evidence supports a finding that speed is at least a consideration.’

The CAFC thus upheld the Board’s finding that motivation to combine was supported by substantial evidence.

II. Nexus

The Court began:

For objective evidence of secondary considerations to be relevant, there must be a nexus between the merits of the claimed invention and the objective evidence. See In re GPAC, 57 F.3d 1573, 1580 (Fed. Cir. 1995). A showing of nexus can be made in two ways: (1) via a presumption of nexus, or (2) via a showing that the evidence is a direct result of the unique characteristics of the claimed invention.

A patent owner is entitled to a presumption of nexus when it shows that the asserted objective evidence is tied to a specific product that “embodies the claimed features, and is coextensive with them.” Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. v. Philip Morris, Inc., 229 F.3d 1120, 1130 (Fed. Cir. 2000).When a nexus is presumed, “the burden shifts to the party asserting obviousness to present evidence to rebut the presumed nexus.” Id.; see also Yita LLC v. MacNeil IP LLC, 69 F.4th 1356, 1365 (Fed. Cir. 2023). The inclusion of noncritical features does not defeat a finding of a presumption of nexus. See, e.g., PPC Broadband, Inc. v. Corning Optical Commc’ns RF, LLC, 815 F.3d 734, 747 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (stating that a nexus may exist “even when the product has additional, unclaimed features”)

Initially, for a presumption of nexus, there is a requirement that the product embodies the invention and is coextensive with it. Brown & Williamson, 229 F.3d at 1130. The CAFC noted that neither party disputed that both the Forward Drive and the Bravo Four S embodied the claimed invention. See, e.g., J.A. 1211, 117:10–25, but emphasized that coextensiveness is a separate requirement. Fox Factory, 944 F.3d at 1374.

Volvo Penta, as Brunswick and the Board note, did not provide sufficient argument on coextensiveness. Rather, it submitted a mere sentence that the Forward Drive is a “commercial embodiment” of the ‘692 Patent and “coextensive with the claims”. The Board found this argument “conclusory” and the CAFC agreed. As above, “[t]he patentee bears the burden of showing that a nexus exists.” Fox Factory, 944 F.3d at 1373 (quoting WMS Gaming Inc. v. Int’l Game Tech., 184 F.3d 1339, 1359 (Fed. Cir. 1999)).

However, the court found that the Boards finding of a lack of nexus, independent of a presumption, not supported by evidence. Specifically, the Board found that Brunswick’s development of the Bravo Four S was “akin to ‘copying,’” and that its “own internal documents indicate that the Forward Drive product guided [Brunswick] to design the Bravo Four S in the first place.” Indeed, the undisputed evidence, as the Board found, shows that boat manufacturers strongly desired Volvo Penta’s Forward Drive and were urging Brunswick to bring a forward drive to market.

The court found that there is therefore a nexus between the unique features of the claimed invention, a tractor-type stern drive, and the evidence of secondary considerations.

III. Objective Indicia

The court began:

Objective evidence of nonobviousness includes: (1) commercial success, (2) copying, (3) industry praise, (4) skepticism, (5) long-felt but unsolved need, and (6) failure of others. See, e.g., Transocean Offshore Deepwater Drilling, Inc. v. Maersk Drilling U.S., Inc., 699 F.3d 1340, 1349–56 (Fed. Cir. 2012). The weight to be given to evidence of secondary considerations involves factual determinations, which we review only for substantial evidence. In re Couvaras, 70 F.4th 1374, 1380 (Fed. Cir. 2023).

The court found that “the Board’s analysis of [this] objective indicia of non-obviousness, including its assignments of weight to different considerations, was overly vague and ambiguous.”

For example, despite recognizing the importance of Brunswick internal documents demonstrating deliberate copying of the Forward Drive, and “finding copying, the Board only afforded this factor ‘some weight.’” The Federal Circuit held that this “assignment of only ‘some weight’” was insufficient in view of its precedent, which generally explains that “copying [is] strong evidence of non-obviousness,” and the “failure by others to solve the problem and copying may often be the most probative and cogent evidence of non-obviousness.” Panduit Corp. v. Dennison Mfg. Co., 774 F.2d 1082, 1099 (Fed. Cir. 1985), cert. granted, judgment vacated on other grounds, 475 U.S. 809 (1986) (“That Dennison, a large corporation with many engineers on its staff, did not copy any prior art device, but found it necessary to copy the cable tie of the claims in suit, is equally strong evidence of nonobviousness.”).

Regarding commercial success, the Board recognized that the record supported, and Brunswick did not contest, that boat manufacturers “strongly desired Volvo Penta’s Forward Drive and were urging Brunswick to bring a forward drive to market.” Nevertheless, the Board only afforded this factor “some weight.” The court stated that this finding was not supported by substantial evidence.

Regarding industry praise, the Board found that although the exhibits submitted “provide praise for the Forward Drive more generally, including mentioning its forward facing propellers, as claimed in the ’692 patent,” it also found that “many of the statements of alleged praise specifically discuss unclaimed features, such as adjustable trim and exhaust-related features.”

The court noted that the Board assigned industry praise, commercial success, and copying all “some weight” without explaining why it gave these three factors the same weight. The court concluded this was ambiguous, and so the Board had “failed to sufficiently explain and support its conclusions. See, e.g., Pers. Web Techs., LLC v. Apple, Inc., 848 F.3d 987, 993 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (remanding in view of the Board’s failure to “sufficiently explain and support [its] conclusions”); In re Nuvasive, Inc., 842 F.3d 1376, 1385 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (same).”

Next, the Court also determined that the Board failed to properly evaluate long-felt but unresolved need. In evaluating the evidence presented by Volvo Penta, the Board dismissed it as merely describing the benefits of the product without indicating a long-felt problem that others had failed to solve. Volvo Penta had cited articles in support of its position, but the Board, without explanation, gave the arguments very little weight. Upon review, the CAFC stated that the articles identified more than mere benefits and “indisputably identifies a long-felt need: safe wakesurfing on stern-drive boats.”

The CAFC touches upon the relevance of the time since the issuance of cited references. The CAFC agreed with the Board that “the mere passage of time from dates of the prior art to the challenged patents” does not indicate nonobviousness “their age can be relevant to long-felt unresolved need.” See Leo Pharm. Prods., 726 F.3d 1346, 1359 (Fed. Cir. 2013) (“The length of the intervening time between the publication dates of the prior art and the claimed invention can also qualify as an objective indicator of nonobviousness.”); cf. Nike, Inc. v. Adidas AG, 812 F.3d 1326, 1338 (Fed. Cir. 2016), overruled on other grounds by Aqua Prods., Inc. v. Matal, 872 F.3d 1290 (Fed. Cir. 2017). The CAFC stated that other factors such as “lack of market demand” can explain why a product was not developed for years, even decades after the prior art. However, when, as here, “evidence demonstrates that there was a market demand for at least” a period of that time (here, the market demand only existed for ten of the fifty years from the prior art reference), the fact that Brunswick itself owned one of the asserted should not be overlooked. That, it is certainly relevant that the asserted patents were long in existence and not obscure, but rather owned by the parties in this case.

Finally, the CAFC held that the Board’s ultimate conclusion that “Brunswick’s “strong evidence of obviousness outweighs Patent Owner’s objective evidence of nonobviousness” lacked a proper explanation for said conclusion.

Thus, ultimately the Court found that the Board failed to properly consider the evidence of objective indicia of nonobviousness and so vacated and remanded for further consideration consistent with the opinion.

Comments:

Motivation to combine a reference does not require a recognition of the primary or only metric by which an invention is measured, so long as it is at least a consideration.

Regarding a presumption of nexus, be reminded that (i) coextensiveness is a separate element and should be addressed as such; and that (ii) “[t]he patentee bears the burden of showing that a nexus exists” and this requires more than conclusory statements. Similarly, the PTO must support a finding of a lack of nexus with evidence not mere conclusory statements.

It also serves as a reminder to be thoughtful and thorough in presenting objective indicia of nonobviousness, not only during IPRs and other forms of litigation, but in prosecution too. Avoid citing arguments in conclusory fashion.

Tags: Motivation > nexus > objective indicia of nonobviousness > obviousness > secondary considerations

Winning on Objective Indicia of Non-Obviousness in an IPR

| March 11, 2022

Quanergy Systems, Inc.. v. Velodyne Lidar USA, Inc.

Opinion by: O’Malley, Newman, and Lourie

Decided on February 4, 2022

Summary:

The Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s validity decisions in two IPRs for Velodyne’s patent on lidar, relying substantially on Velodyne’s objective evidence of non-obviousness. Quanergy’s appeal attacked the PTAB’s presumption of a nexus between Velodyne’s product and the claimed invention. In particular, Quanergy challenged the nexus presumption by arguing that there were unclaimed features that attributed to the significance of Velodyne’s products, instead of the claimed invention. The Federal Circuit found the PTAB’s reasoning for how each alleged unclaimed feature resulted directly from claim limitations – such that Velodyne’s products are essentially the claimed invention – were found to be both adequate and reasonable.

Procedural History:

Quanergy Systems, Inc. (Quanergy) challenged the validity of Velodyne Lidar USA, Inc. (Velodyne) U.S. Patent 7,969,558 in two inter partes review (IPR) proceedings before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) as being obvious. The PTAB sustained the validity of the ‘558 patent. The Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s decision.

Background:

The ‘558 patent relates to a lidar-based 3-D point cloud measuring system, useful in autonomous vehicles. “Lidar” is an acronym for “Laser Imaging Detection and Ranging.” Lidar technology uses a pulse of light to measure distance to objects. Each pulse of light for measurement results in one “pixel” and a collection of pixels is called a “point cloud.” A 3-D point cloud may be achieved by making measurements with the light pulses in up-down directions, as well as in 360 degrees. Representative claim 1 is as follows:

A lidar-based 3-D point cloud system comprising:

a support structure;

a plurality of laser emitters supported by the support structure;

a plurality of avalanche photodiode detectors supported by the support structure; and

a rotary component configured to rotate the plurality of laser emitters and the plurality of avalanche photodiode detectors at a speed of at least 200 RPM.

Quanergy relied on a Mizuno reference that uses a “triangulation system” measuring the distance to an object by detecting light reflected from the object to image sensors. Quanergy also relied on a Berkovic reference that teaches the triangulation technique, as well as a time-of-flight sensing technique. To win on obviousness, Quanergy relied on a broad interpretation of “lidar” to encompass both triangulation systems and “pulsed time-of-flight (ToF) lidar.”

However, the PTAB construed “lidar” to mean pulsed time-of-flight lidar because the ‘558 specification exclusively focuses on pulsed time-of-flight lidar in which distance is measured by the “time” of travel (i.e., flight) of the laser pulse to and from an object. The PTAB also found that Mizuno does not address a time-of-flight lidar system. Instead, Mizuno’s triangulation system is a short-range measuring device. And, the PTAB held that the skilled artisan would not have had a reasonable expectation of success in modifying Mizuno’s device to use pulsed time-of-flight lidar because Quanergy’s expert did not explain how or why a skilled artisan would have had an expectation of success in overcoming the problems in implementing a pulsed time-of-flight sensor in a short range measurement system such as that of Mizuno’s. Indeed, the Berkovic reference was found to suggest that the accuracy of pulsed time-of-flight lidar measurements degrades in shorter ranges, such as in Mizuno’s system.

But, more importantly, the PTAB relied substantially on Velodyne’s objective evidence of non-obviousness, which “clearly outweighs any presumed showing of obviousness by Quanergy” even if Quanergy satisfied obviousness with respect to the first three of the four Graham v John Deere factors (i.e., (1) scope and content of the prior art, (2) difference between the prior art and the claims at issue, (3) level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art, and (4) any objective indicia of nonobviousness).

Decision:

As for the initial claim construction issue regarding “lidar,” the Federal Circuit agreed with the strength of the intrinsic record focusing exclusively on pulsed time-of-flight lidar, collecting time-of-flight measurements, and taking note of the specification’s boasted ability to “collect approximately 1 million time of flight (ToF) distance points per second, overcoming commercial point cloud systems inability to meet the demands of autonomous vehicle navigation. Indeed, the court found Quanergy’s arguments for a broader construction to be inconsistent with the specification and therefore unreasonable.

Quanergy also challenged the PTAB’s presumption of a nexus between the claimed invention and Velodyne’s evidence of an unresolved long-felt need, industry praise, and commercial success.

To accord substantial weight to Velodyne’s objective evidence, that evidence must have a “nexus” to the claims, i.e., there must be a “legally and factually sufficient connection” between the evidence and the patented invention.

The Federal Circuit may presume a nexus to exist “when the patentee shows that the asserted objective evidence is tied to a specific product and that product ‘embodies the claimed features, and is co-extensive with them.” This co-extensiveness does not require a patentee to prove perfect correspondence between the product and the patent claim. Instead, it is sufficient to demonstrate that “the product is essentially the claimed invention.” In this analysis, “the fact finder must consider the unclaimed features of the stated products to determine their level of significance and their impact on the correspondence between the claim and the products.” “Some unclaimed features ‘amount to nothing more than additional insignificant features,’ such that presuming nexus is still appropriate.” “Other unclaimed features, like a ‘critical’ unclaimed feature that is claimed by a different patent and that materially impacts the product’s functionality, indicate that the claim is not coextensive with the product.”

This presumption of a nexus is rebuttable. However, a patent challenger may not rebut the presumption of nexus with argument alone. The patent challenger may present evidence showing that the proffered objective evidence was “due to extraneous factors other than the patented invention” such as unclaimed features or external factors like improvements in marketing or superior workmanship.

Here, Quanergy argued that the PTAB failed to consider the issue of unclaimed features before presuming a nexus and failed to provide an adequate factual basis or reasoned explanation dismissing the unclaimed features argument. Quanergy argued that Velodyne’s evidence relies on unclaimed features, including high frame-rate, dense 3D point cloud with a wide field of view and collecting measurements in an outward facing lidar for 360 degree azimuth and 26 degree vertical arc. And, such unclaimed features are critical and materially impact the functionality of Velodyne’s products. Therefore, the requisite presumption of a nexus does not exist.

However, the court found that the PTAB considered, and adequately/reasonably did so, the unclaimed features arguments, reasonably finding that Veloydyne’s products embody the full scope of the claimed invention and that the claimed invention is not merely a subcomponent of those products. First, the PTAB credited Velodyne’s expert testimony providing a detailed analysis mapping claim 1 to description of Velodyne’s product literature. Second, the claims call for a 3-D point cloud and the density of the cloud and the 360 degree horizontal field of view (i.e., the ”unclaimed features”) “result directly” from the limitation for “[rotating] the plurality of laser emitters and the plurality of avalanche photodiode detectors at a speed of at least 200 RPM.” The “3-D” feature necessarily infers both horizontal and vertical fields of view. The PTAB also pointed to (1) contemporaneous news articles describing the long-felt need for a lidar sensor that could capture points rapidly in all directions and produce a sufficiently dense 3-D point cloud for autonomous navigation, (2) articles praising Velodyne as the top lidar producer and Velodyne’s products, and (3) financial information and articles reflecting Velodyne’s revenue and market share to show commercial success.

The court also found the PTAB’s analysis of those unclaimed features arguments to be commensurate with Quanergy’s presentation of the issue. Here, the court found Quanergy’s unclaimed features arguments to be merely skeletal, undeveloped arguments. In contrast, the PTAB’s explanation of how each alleged unclaimed feature results directly from claim limitations – such that Velodyne’s products are essentially the claimed invention – were found to be both adequate and reasonable.

Quanergy also presented new arguments (not previously presented to the PTAB) that, to obtain the dense 3-D point cloud, Velodyne’s products require the unclaimed critical features of (1) more than 2 laser emitters, (2) a high pulse rate, (3) vertical angular separation between pairs of emitters and detectors, and (4) a rotation speed significantly greater than 200 RPM. However, the court held that these new arguments, presented only on appeal, were forfeited.

Takeaways:

- This case is a good primer for how to best present or attack objective indicia of non-obviousness.

- One key to success for objective indicia of non-obviousness is expert testimony mapping claimed features to product literature and explaining how and why that description of the product is essentially the claimed invention. Other helpful evidence includes contemporaneous news articles about the long-felt need, praise for the subject product, and financial information/articles showing the company’s commercial success, presumably tied to the subject product.

- If unclaimed features are asserted to attack a presumption of nexus, expert testimony explaining how those alleged unclaimed features are direct results from claimed limitations, so as to side step the attack, is helpful.

- Skeletal arguments are insufficient. If making an unclaimed features argument, it is best to flesh it out before the PTAB in detail, otherwise it will be considered forfeited if newly presented on appeal.

Nexus for Secondary Considerations requires Coextensiveness between a product and the claimed invention

| June 26, 2020

Fox Factory, Inc. v. SRAM, LLC

May 18, 2020

Lourie, Mayer and Wallach. Opinion by Lourie.

Summary:

SRAM sued Fox Factory for infringing U.S. Patent 9,291,250 (the ‘250 patent) and the parent patent U.S. Patent 9,182,027 (the ‘027 patent) to bicycle chainrings having teeth that alternate between widened teeth that better fit a gap between outer plates of a chain and narrower teeth to fit a gap between inner plates of a chain. Fox Factory filed IPRs against each patent. SRAM provided evidence of secondary considerations and argued that a greater than 80% gap-filling feature of the X-Sync chainring was crucial to its success for solving chain retention problem. The PTAB held that both patents are not unpatentable as obvious relying in part on secondary consideration evidence provided by SRAM. On appeal, the CAFC vacated the PTAB’s decision with regard to the ‘027 patent because the SRAM X-Sync chainring is not coextensive with the claims of the ‘027 patent that do not recite the greater than 80% gap-filling feature. However, the CAFC affirmed the PTAB’s decision for the ‘250 patent because the claims include the greater than 80% gap-filling feature.

Details:

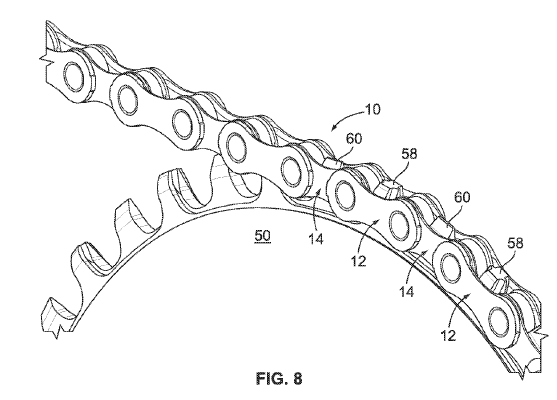

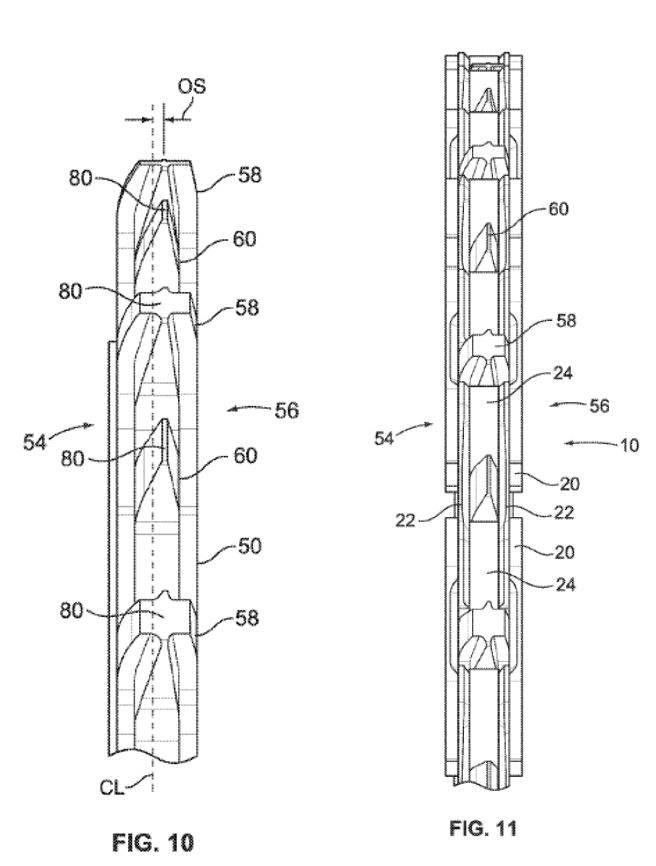

The ’250 patent and the ‘027 patent are to bicycle chainrings. Some figures of the patents are provided below.

This chainring is designed to be a solitary chainring that does not need to switch between different size chainrings. Since it is a solitary chainring, the chainring can be designed to provide a tighter fit with the chain. A conventional chain has links that are alternatingly narrow and wide, but the conventional chainring has teeth that are all the same size. SRAM designed a chairing to have alternating teeth having widened teeth to fit the wide gaps and narrow teeth to fit the narrower gaps. SRAM’s product the X-Sync chainring that implements this design has been praised for its chain retention.

Claim 1 of the ‘250 patent is provided:

1. A bicycle chainring of a bicycle crankset for engagement with a drive chain, comprising:

a plurality of teeth extending from a periphery of the chainring wherein roots of the plurality of teeth are disposed adjacent the periphery of the chainring;

the plurality of teeth including a first group of teeth and a second group of teeth, each of the first group of teeth wider than each of the second group of teeth; and

at least some of the second group of teeth arranged alternatingly and adjacently between the first group of teeth,

wherein the drive chain is a roller drive chain including alternating outer and inner chain links defining outer and inner link spaces, respectively;

wherein each of the first group of teeth is sized and shaped to fit within one of the outer link spaces and each of the second group of teeth is sized and shaped to fit within one of the inner link spaces; and

wherein a maximum axial width about halfway between a root circle and a top land of the first group of teeth fills at least 80 percent of an axial distance defined by the outer link spaces.

In the IPR for the ‘250 patent, Fox Factory cited JP S56-42489 to Shimano and U.S. Patent 3,375,022 to Hattan. Shimano teaches a bicycle chainring with widened teeth to fit into the outer chain links of a conventional chain. Hattan describes that a chainring’s teeth should fill between 74.6% and 96% of the inner chain link space. Fox Factory argued that the claims would have been obvious because one of ordinary skill in the art would have seen the utility in designing a chainring with widened teeth to improve chain retention as taught by Shimano, and one of ordinary skill in the art would have looked to Hattan’s teaching with regard to the percentage of the link space that should be filled.

The PTAB held the claims to be non-obvious because of the axial fill limitation “at the midpoint of the teeth.” The PTAB found that Hattan taught the fill percentage at the bottom of the tooth instead of at the midpoint. The PTAB also found that SRAM’s evidence of secondary considerations rebutted Fox Factory’s arguments of obviousness.

On appeal, Fox Factory argued that the only difference between the prior art and the claimed invention is that the fill limitation is measured halfway up the tooth. Regarding secondary considerations, Fox Factory argued that a nexus between the claimed invention and the evidence of success of the X-Sync chainring was not demonstrated because the success is due to other various unclaimed aspects of the X-Sync chainring.

The CAFC stated that Fox Factory is correct that “a mere change in proportion … involves no more than mechanical skill, rather than the level of invention required by 35 U.S.C. § 103.” However, the CAFC stated that the PTAB “found that SRAM’s optimization of the X-Sync chainring’s teeth, as claimed in the ‘250 patent, displayed significant invention.” The CAFC pointed out that SRAM provided evidence that the success of the X-Sync chainring surprised skilled artisans, evidence of industry skepticism and subsequent praise, and evidence of a long-felt need to solve chain retention problems. The X-Sync chainring also won an award for “Innovation of the Year.” Based on the evidence, the CAFC stated that the PTAB did not err in concluding that the evidence of secondary considerations defeated the contention of routine optimization.

Fox Factory argued that the CAFC’s previous decision on the ‘027 patent requires vacatur in this case. In the appeal of the IPR for the ‘027 patent the CAFC stated that the PTAB misapplied the legal requirement of showing a nexus between evidence of secondary considerations and the obviousness of the claims of the patent. The CAFC stated that the patent owner must show that “the product from which the secondary considerations arose is coextensive with the claimed invention.” In the IPR for the ‘250 patent, SRAM argued that the greater than 80% gap-filling feature of the X-Sync chainring was crucial to its success. But the claims of the ‘027 patent do not include this greater than 80% gap filling feature. Thus, in the ‘027 appeal, the CAFC stated that no reasonable factfinder could decide that the X-Sync chainring was coextensive with a claim that did not include the greater than 80% gap filling feature, and vacated the decision of the PTAB.

In this case, the CAFC pointed out that the claims of the ‘250 patent include the greater than 80% gap filling feature, and thus, the X-Sync chainring is coextensive with the claims. The CAFC also stated that the unclaimed features relied on by Fox Factory as contributing to the success are to some extent incorporated into the 80% gap-filling feature. Thus, the CAFC found that substantial evidence supports the PTAB’s findings on secondary considerations and nexus, and the CAFC stated that they agree with the PTAB’s conclusion that the claims of the ‘250 patent would not have been obvious.

Comments

When arguing secondary considerations, make sure that there is nexus between the evidence and the claims. Specifically, you need to make sure that the product from which the secondary considerations arose is “coextensive” with the claimed invention. A product that falls within the scope of the claim is not necessarily coextensive with the claim.

This case is also a reminder to include claims having varying scope. In this case, SRAM’s claims survived because of the 80% gap-filling feature which was not included in the claims of the parent patent.

A Good Fry: Patent on Oil Quality Sensing Technology for Deep Fryers Survives Inter Partes Review

| October 4, 2019

Henny Penny Corporation v. Frymaster LLC

September 12, 2019

Before Lourie, Chen, and Stoll (Opinion by Lourie)

Summary

In an appeal from an inter partes review, the Federal Circuit affirmed the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s decision to uphold the validity of a patent relating to oil quality sensing technology for deep fryers. The Board found, and the Federal Circuit agreed, that the disadvantages of pursuing the challenger’s proposed modification of the prior art weighed against obviousness, in the absence of some articulated rationale as to why a person of ordinary skill in the art would have pursued that modification. In addition, the Federal Circuit reiterated that as a matter of procedure, the scope of an inter partes review is limited to the theories of unpatentability presented in the original petition.

Details

Fries are among the most common deep-fried foods, and McDonald’s fries may still be the most popular and highest-consumed worldwide. But, there would be no McDonald’s fries without a deep fryer and a good pot of oil, and Frymaster LLC (“Frymaster”) is the maker of some of McDonald’s deep fryers.

During deep frying, chemical and thermal interactions between the hot frying oil and the submerged food cause the food to cook. These interactions degrade the quality of the oil. In particular, chemical reactions during frying generate new compounds, including total polar materials (TPM), that can change the oil’s physical properties and electrical conductivity.

Frymaster’s fryers are equipped with integrated oil quality sensors (OQS), which monitor oil quality by measuring the oil’s electrical conductivity as an indicator of the TPM levels in the oil. This sensor technology is embodied in Frymaster’s U.S. Patent No. 8,497,691 (“691 patent”).

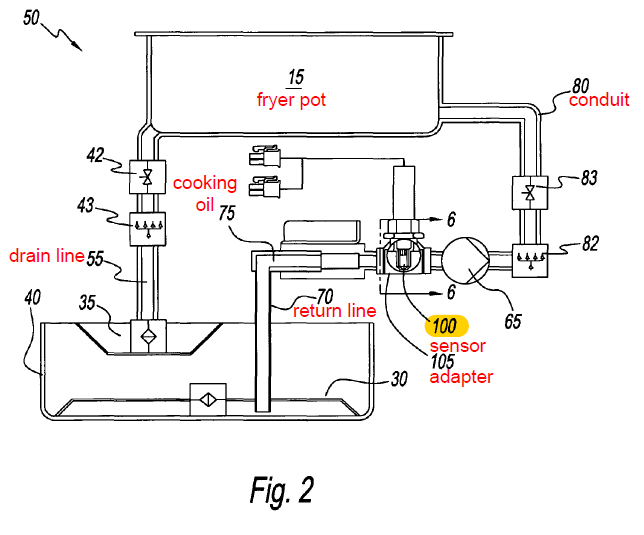

The 691 patent describes an oil quality sensor that is integrated directly into the circulation of cooking oil in a deep fryer, and is capable of taking measurements at the deep fryer’s operational temperatures of 150-180°C, i.e., without cooling the hot oil.

Claim 1 of the 691 patent is representative:

1. A system for measuring the state of degradation of cooking oils or fats in a deep fryer comprising:

at least one fryer pot;

a conduit fluidly connected to said at least one fryer pot for transporting cooking oil from said at least one fryer pot and returning the cooking oil back to said at least one fryer pot;

a means for re-circulating said cooking oil to and from said fryer pot; and

a sensor external to said at least on[e] fryer pot and disposed in fluid communication with said conduit to measure an electrical property that is indicative of total polar materials of said cooking oil as the cooking oil flows past said sensor and is returned to said at least one fryer pot;

wherein said conduit comprises a drain pipe that transports oil from said at least one fryer pot and a return pipe that returns oil to said at least one fryer pot,

wherein said return pipe or said drain pipe comprises two portions and said sensor is disposed in an adapter installed between said two portions, and

wherein said adapter has two opposite ends wherein one of said two ends is connected to one of said two portions and the other of said two ends is connected to the other of said two portions.

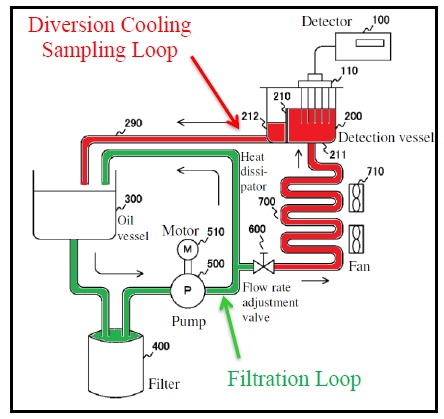

Figure 2 of the 691 patent illustrates the structure of Frymaster’s system:

Henny Penny Corporation (HPC) is a competitor of Frymaster, and initiated an inter partes review of the 691 patent.

In its petition, HPC challenged claim 1 of the 691 patent as being obvious over Kauffman (U.S. Patent No. 5,071,527) in view of Iwaguchi (JP2005-55198).

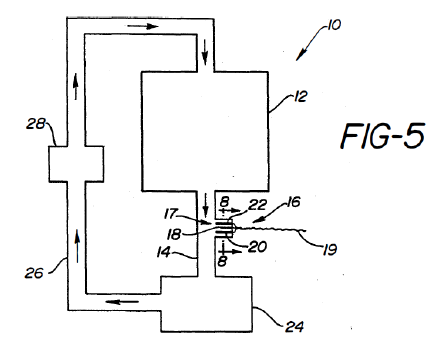

Kauffman taught a system for “complete analysis of used oils, lubricants, and fluids”. The system included an integrated electrode positioned between drain and return lines connected to a fluid reservoir. The electrode measured conductivity and current to monitor antioxidant depletion, oxidation initiator buildup, product buildup, and/or liquid contamination. Kauffman’s system operated at 20-400°C. However, Kauffman did not teach monitoring TPMs.

Iwaguchi taught monitoring TPMs to gauge quality of oil in deep fryers. However, Iwaguchi cooled the oil to 40-80°C before taking measurements. If the oil temperature was outside the disclosed range, Iwaguchi’s system would register an error. Specifically, oil was diverted from the frying pot to a heat dissipator where the oil was cooled to the appropriate temperature, and then to a detection vessel where a TPM detector measured the electrical properties of the oil to detect TPMs. Iwaguchi taught that cooling relieved heat stress on the detector, prevented degradation, and obviated the need for large conversion tables.

The parties’ dispute focused on the sensor feature of the 691 patent.

In the initial petition, HPC argued simply that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have found it obvious to modify Kauffman’s system to “include the processor and/or sensor as taught by Iwaguchi.”

In its patent owner’s response, Frymaster disputed HPC’s proposed modification. Frymaster argued that Iwaguchi’s “temperature sensitive” detector would be inoperable in an “integrated” system such as that taught in Kauffman, unless Kauffman’s system was further modified to add an oil diversion and cooling loop. However, such an addition would have been complex, inefficient, and undesirable to those skilled in the art.

In its reply, HPC changed course and argued that it was unnecessary to swap the electrode in Kauffman’s system for Iwaguchi’s detector. HPC argued that Kauffman’s electrode was capable of monitoring TPMs by measuring conductivity, and that Iwaguchi was relevant only for teaching the general desirability of using TPMs to assess oil quality.

However, whereas HPC’s theory of obviousness in its original petition was based on a modification of the physical structure of Kauffman’s system, HPC’s reply proposed changing only the oil quality parameter being measured. During the oral hearing before the Board, HPC’s counsel even admitted to this shift in HPC’s theory of obviousness.

In its final written decision, the Board determined, as a threshold matter of procedure, that HPC impermissibly presented a new theory of obviousness in its reply, and that the patentability of the 691 patent would be assessed only against the grounds asserted in HPC’s original petition.

The Board’s final written decision thus addressed only whether the person skilled in the art would have been motivated to “include”—that is, integrate—Iwaguchi’s detector into Kauffman’s system. The Board found no such motivation.

The Board’s reasoning largely mirrored Frymaster’s arguments. Kauffman’s system did not include a cooling mechanism that would have allowed Iwaguchi’s temperature-sensitive detector to work. Integrating Iwaguchi’s detector into Kauffman’s system would therefore necessitate the addition of the cooling mechanism. The Board agreed that the disadvantages of such additional construction outweighed the “uncertain benefits” of TPM measurements over the other indicia of oil quality already being monitored in Kauffman.

On appeal, HPC raised two issues: first, the Board construed the scope of HPC’s original petition overly narrowly; and second, the Board erred in its conclusion of nonobviousness.[1]

The Federal Circuit sided with the Board on both issues.

On the first issue, the Federal Circuit did a straightforward comparison of HPC’s petition and reply. In the petition, HPC proposed a physical substitution of Iwaguchi’s detector for Kauffman’s electrode. In the reply, HPC proposed using conductivity measured by Kauffman’s electrode as a basis for calculating TPMs. The apparent differences between the two theories of obviousness, together with the “telling” confirmation of HPC’s counsel during oral hearing that the original petition espoused a physical modification, made it easy for the Federal Circuit to agree with the Board’s decision to disregard HPC’s alternative theory raised in its reply.

The Federal Circuit reiterated the importance of a complete petition:

It is of the utmost importance that petitioners in the IPR proceedings adhere to the requirement that the initial petition identify ‘with particularity’ the ‘evidence that supports the grounds for the challenge to each claim.

On the second issue of obviousness, HPC argued that the Board placed undue weight on the disadvantages of incorporating Iwaguchi’s TPM detector into Kauffman’s system.

Here, the Federal Circuit reiterated “the longstanding principle that the prior art must be considered for all its teachings, not selectively.” While “[t]he fact that the motivating benefit comes at the expense of another benefit…should not nullify its use as a basis to modify the disclosure of one reference with the teachings of another”, “the benefits, both lost and gained, should be weighed against one another.”

The Federal Circuit adopted the Board’s findings on the undesirability of HPC’s proposed modification of Kauffman, agreeing that the “tradeoffs [would] yield an unappetizing combination, especially because Kauffman already teaches a sensor that measures other indicia of oil quality.”

At first glance, the nonobviousness analysis in this decision seems to involve weighing the disadvantages and advantages of the proposed modification. However, looking at the history of this case, I think the problem with HPC’s arguments was more fundamentally that they never identified a satisfactory motivation to make the proposed modification. HPC’s original petition argued that the motivation for integrating Iwaguchi’s detector into Kauffman’s system was to “accurately” determine oil quality. This “accuracy” argument failed because it was questionable whether Iwaguchi’s detector would even work at the operating temperature of a deep fryer. Further, HPC did not argue that the proposed modification was a simple substitution of one known sensor for another with the predictable result of measuring TPMs. And when Kauffman argued that the substitution was far from simple, HPC failed to counter with adequate reasons why the person skilled in the art would have pursued the complex modification.

Takeaway

- The petition for a post grant review defines the scope of the proceeding. Avoid being overly generic in a petition for post grant review. It may not be possible to fill in the details later.

- Context matters. If an Examiner is selectively citing to isolated disclosures in a prior art out of context, consider whether the context of the prior art would lead away from the claimed invention.

- The MPEP is clear that the disadvantages of a proposed combination of the prior art do not necessarily negate the motivation to combine (see, e.g., MPEP 2143(V)). The disadvantages should preferably nullify the Examiner’s reasons for the modification.

[1] On the issue of obviousness, HPC also objected to the Board’s analysis of Frymaster’s proffered evidence of industry praise as secondary considerations. This objection is not addressed here.

Not All Secondary Considerations are Probative of Nonobviousness

| July 23, 2014

Galderma Labs v. Tolmar, Inc.

December 11, 2013

Before NEWMAN, BRYSON, and PROST, Circuit Judges. Opinion for the court filed by Circuit Judge PROST. Dissenting opinion filed by Circuit Judge NEWMAN.

SUMMARY

This Hatch-Waxman case is based on Tolmar’s filing of an Abbreviated New Drug Application (“ANDA”) seeking approval to market a generic drug (Differin® Gel,0.3%), which is a topical medication containing 0.3% by weight adapalene approved for the treatment of acne.

Tags: commercial success > secondary considerations > teaching away > unexpected results

CAFC Reminds the Patent Office to Play Fair When Issuing New Grounds of Rejection and Evaluating Objective Evidence of Non-Obviousness

| October 3, 2013

Rambus Inc. v. Rea

September 24, 2013

Panel of Moore, Linn, and O’Malley, Opinion by Moore

Summary

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Rambus Inc. v. Rea reminds Examiners and the Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences (now the Patent Trial and Appeal Board) that procedural checks remain in place for issuing new grounds of rejection. Examiners and the Board cannot bury a new ground of rejection in a decision, without ensuring that a patent applicant has had a fair opportunity to respond to the rejection. Indeed, whether the applicant has had a fair opportunity to react to the thrust of the rejection is reiterated as the ultimate determination of whether a rejection is considered “new”.

In line with the Federal Circuit’s recent decision in Leo Pharmaceutical Products v. Rea, Rambus is also a reminder that objective evidence of non-obviousness must be given due consideration and weight. Examiners and the Board cannot undercut an applicant’s objective evidence of non-obviousness through an overly stringent interpretation of the nexus and “commensurate in scope” requirements.

Tags: obviousness > procedural issues > reexamination > secondary considerations

Prior art can show what the claims would mean to those skilled in the art

| December 5, 2012

ArcelorMittal v. AK Steel Corp.

November 30, 2012

Panel: Dyk, Clevenger, and Wallach. Opinion by Dyk.

Summary:

The U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware held that defendants AK Steel did not infringe plaintiffs ArcelorMittal’s U.S. Patent No. 6,296,805 (the ‘805 patent), and that the asserted claims were invalid as anticipated and obvious based on a jury verdict.

ArcelorMittal appealed the district court’s decision. On appeal, the CAFC upheld the district court’s claim construction in part and reverse it in part. With regard to anticipation, the CAFC reversed the jury’s verdict of anticipation. With regard to obviousness, the CAFC held that a new trial is required because the district court’s claim construction error prevented the jury from properly considering ArcelorMittal’s evidence of commercial success.

미국 델라웨어주 연방지방법원 (U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware)은 원고 (ArcelorMittal)가 피고 (AK Steel)를 상대로 낸 특허 침해 소송에서 원고의 특허 (U.S. Patent No. 6,296,805)가 예견가능성 (anticipation) 및 자명성 (obviousness) 기준을 통과하지 못하였다는 배심원의 판단을 바탕으로 피고가 원고의 특허를 침해하지 않았다고 판결하였다.

이에 불복하여 원고는 연방항소법원 (U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit)에서 상고 (appeal) 하였으며, 연방항소법원은 지방법원의 청구항 해석 (claim construction)에 대해 일정 부분은 확인하였으나, 나머지 부분은 번복하였다.

예견가능성과 관련하여 연방항소법원은 배심원의 예견가능성 판단과 다른 결정을 내렸다.

자명성과 관련해서는 연방지방법원의 잘못된 청구항 해석으로 인하여 배심원이 원고의 상업적 성공 (commercial success) 증거를 고려하지 않았기때문에 재심 (new trial)이 필요하다고 판결하였다.

Tags: anticipation > claims construction > commercial success > extrinsic evidence > intrinsic evidence > obviousness > prior art > secondary considerations

Unexpected results, not disclosed in the specification, of a compound may overcome a prima facie case of obviousness

| April 2, 2012

Genetics Institute, LLC v. Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics, Inc.

August 23, 2011

Panel: Lourie, Plager and Dyk. Opinion by Lourie. Concurrence-in-part and dissent-in part by Dyk.

Summary:

Today, we bring you the first in a series of three articles regarding an important case from last year. This article discusses the following question:

Question: Can evidence of unexpected results of a compound be used to overcome a prima facie case of obviousness, where the unexpected result is not disclosed in the specification as originally filed?

Answer: Yes.

Evidence of unexpected results to a property of a compound, where the unexpected result is not disclosed in the specification as originally filed, can be used to overcome a prima facie case of obviousness.

Tags: comparative results > interference > obviousness > secondary considerations > unexpected data