When there is competing evidence as to whether a prior art reference is a proper primary reference, an invalidity decision cannot be made as a matter of law at summary judgment

| April 29, 2020

Spigen Korea Co., Ltd. v. Ultraproof, Inc., et al.

April 17, 2020

Newman, Lourie, Reyna (Opinion by Reyna; Dissent by Lourie)

Summary

Spigen Korea Co., Ltd. (“Spigen”) sued Ultraproof, Inc. (“Ultraproof”) for infringement of its multiple patents directed to designs for cellular phone cases. The district court held that as a matter of law, Spigen’s design patents were obvious over prior art references, and granted Ultraproof’s motion for summary judgment of invalidity. However, based on the competing evidence presented by the parties, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the “CAFC”) reversed and remanded, holding that a reasonable factfinder could conclude that a genuine dispute of material fact exists as to whether the primary reference was proper.

原告Spigen社は、自身の所有する複数の携帯電話ケースに関する意匠特許を被告Ultraproof社が侵害しているとして、提訴した。地裁は、原告の意匠特許は、先行技術文献により自明であるとして、裁判官は被告のサマリージャッジメントの申し立てを容認した。しかしながら、連邦控訴巡回裁判所(CAFC)は、双方の提示している証拠には「重要な事実についての真の争い(genuine dispute of material fact)」があるとして、地裁の判決を覆し、事件を差し戻した。

Details

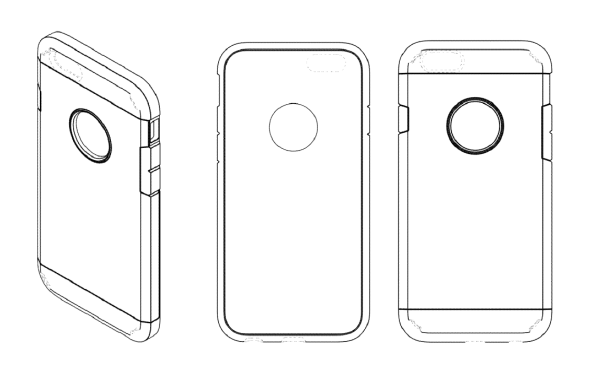

Spigen is the owner of U.S. Design Patent Nos. D771,607 (“the ’607 patent”), D775,620 (“the ’620 patent”), and D776,648 (“the ’648 patent”) (collectively the “Spigen Design Patents”), each of which claims a cellular phone case. Figures 3-5 of the ’607 patent are as shown below:

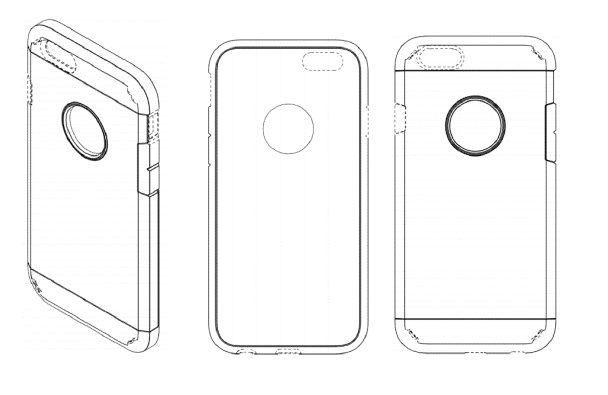

The ’620 patent disclaims certain elements shown in the ’607 patent, and Figures 3-5 of the ’620 patent are shown below:

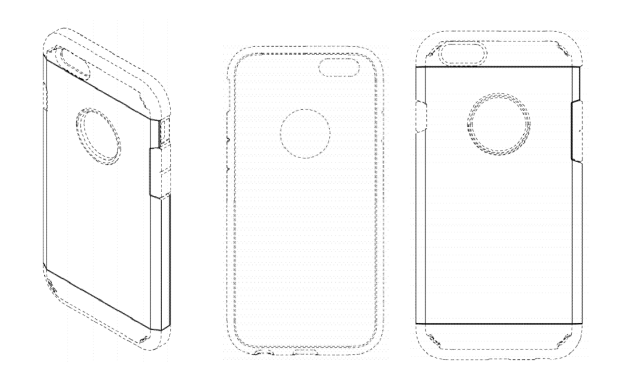

Finally, the ’648 patent disclaims most of the elements present in the ’620 patent and the ’607 patent, Figures 3-5 of which are shown below:

On February 13, 2017, Spigen sued Ultraproof for infringement of Spigen Design Patents in the United States District Court for the Central District of California. Ultraproof filed a motion for summary judgment of invalidity of Spigen Design Patents, arguing that the Spigen Design Patents were obvious as a matter of law in view of a primary reference, U.S. Design Patent No. D729,218 (“the ’218 patent”) and a secondary reference, U.S. Design Patent No. D772,209 (“the ’209 patent”). Spigen opposed the motion arguing that 1) the Spigen Design Patents were not rendered obvious by the primary and secondary reference as a matter of law; and 2) various underlying factual disputes precluded summary judgment. The district court held that as a matter of law, the Spigen Design Patents were obvious over the ’218 patent and the ’209 patent, and granted summary judgment of invalidity in favor of Ultraproof. Ultraproof then moved for attorneys’ fees, which the district court denied. Spigen appealed the district court’s obviousness determination, and Ultraproof cross-appealed the denial of attorneys’ fees.

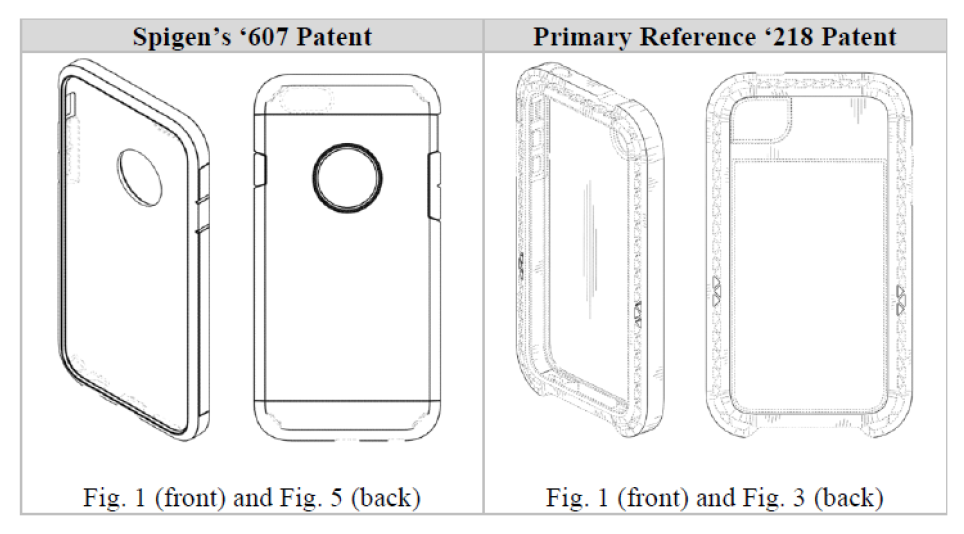

On appeal, Spigen presented several arguments as to why the district court’s grant of summary judgment should be reversed. First, Spigen argued that there is a material factual dispute over whether the ’218 patent is a proper primary reference that precludes summary judgment. The CAFC agreed. The CAFC explained, citing Titan Tire Corp. v. Case New Holland, Inc., 566 F.3d 1372, 1380-81 (Fed. Cir. 2009) (quoting Durling v. Spectrum Furniture Co., 101 F.3d 100, 103 (Fed. Cir. 1996)) that the ultimate inquiry for obviousness “is whether the claimed design would have been obvious to a designer of ordinary skill who designs articles of the type involved,” which is a question of law based on underlying factual findings. Whether a prior art design qualifies as a “primary reference” is an underlying factual issue. The CAFC went on to explain that a “primary reference” is a single reference that creates “basically the same” visual impression, and for a design to be “basically the same,” the designs at issue cannot have “substantial differences in the[ir] overall visual appearance[s].” Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 678 F.3d 1314, 1330 (Fed. Cir. 2012). A trial court must deny summary judgment if based on the evidence before the court, a reasonable jury could find in favor of the non-moving party. Here, the district court errored in finding that the ’218 patent was “basically the same” as the Spigen Design Patents despite there being “slight differences,” as a reasonable factfinder could find otherwise.

Spigen’s expert testified that the Spigen Design Patents and the ’218 patent are not “at all similar, let alone ‘basically the same.’” Spigen’s expert noted that the ’218 patent has the following features that are different from the Spigen Design Patents:

- unusually broad front and rear chamfers and side surfaces

- substantially wider surface

- lack of any outer shell-like feature or parting lines

- lack of an aperture on its rear side

- presence of small triangular elements illustrated on its chamfers

In contrast, Ultraproof argued that the ’218 patent was “basically the same” because of the presence of the following features:

- a generally rectangular appearance with rounded corners

- a prominent rear chamfer and front chamfer

- elongated buttons corresponding to the location of the buttons of the underlying phone

Ultraproof stated that the only differences were the “circular cutout in the upper third of the back surface and the horizontal parting lines on the back and side surfaces.”

Based on the competing evidence in the record, the CAFC found that a reasonable factfinder could conclude that the ’218 patent and the Spigen Design Patents are not basically the same. T

The CAFC determined that a genuine dispute of material fact exists as to whether the ’218 patent is a proper primary reference, and therefore, reversed the district court’s grant of summary judgment of invalidity and remanded the case for further proceedings.

Takeaway

When there is competing evidence in the record, the determination of whether a prior art reference creates “basically the same” visual impression, and therefore a proper primary reference, is a matter that cannot be decided at summary judgment.