Inventor declaration not related to what is claimed or discussed in the patent would not help the patent to survive from patent eligibility attack in the pleading stage

| March 8, 2024

INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MACHINES CORPORATION v. ZILLOW GROUP, INC., ZILLOW, INC.

Decided: January 9, 2024

Hughes (author), Prost, and Stoll

Summary:

The Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision holding that the claims of two IBM’s patents are directed to patent ineligible subject matter under §101, and properly granting Zillow’s motion to dismiss under FRCP 12(b)(6).

Details:

IBM appealed a decision from the Western District of Washington, where the district court granted Zillow’s motion to dismiss under FRCP 12(b)(6). The district court held that all patent claims asserted against Zillow by IBM were directed to ineligible subject matter under 35 U.S.C. §101.

At issue in this appeal were IBM’s two patents – U.S. Patent Nos. 6,778,193 and 6,785,676.

The ’193 patent

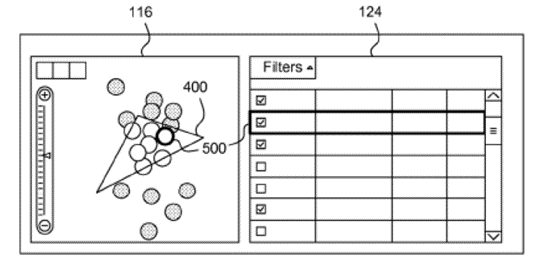

The ’193 patent is directed to a “graphical user interface for a customer self-service system that performs resource search and selection.”

This patent is directed to improving how search results are displayed to a user by providing three visual workspaces: (1) a user begins by entering their search query into a “Context Selection Workspace”; (2) a user can further specify the details of their search in a “Detail Specification Workspace”; and (3) a user can view the results of their search in a “Results Display Workspace.”

Independent claim 1 is a representative claim:

1. A graphical user interface for a customer self service system that performs resource search and selection comprising:

a first visual workspace comprising entry field enabling entry of a query for a resource and, one or more selectable graphical user context elements, each element representing a context associated with the current user state and having context attributes and attribute values associated therewith;

a second visual workspace for visualizing the set of resources that the customer self service system has determined to match the user’s query, said system indicating a degree of fit of said determined resources with said query;

a third visual workspace for enabling said user to select and modify context attribute values to enable increased specificity and accuracy of a query’s search parameters, said third visual workspace further enabling said user to specify resource selection parameters and relevant resource evaluation criteria utilized by a search mechanism in said system, said degree of fit indication based on said user’s context, and said associated resource selection parameters and relevant resource evaluation criteria; and,

a mechanism enabling said user to navigate among said first, second and third visual workspaces to thereby identify and improve selection logic and response sets fitted to said query.

The ’676 patent

The ’676 patent is directed to enhancing how search results are displayed to users by disclosing a four-step process of annotating resource results obtained in a customer self service system that performs resource search and selection.”

Independent claim 14 is a representative claim:

14. A method for annotating resource results obtained in a customer self service system that performs resource search and selection, said method comprising the steps of:

a) receiving a resource response set of results obtained in response to a current user query;

b) receiving a user context vector associated with said current user query, said user context vector comprising data associating an interaction state with said user and including context that is a function of the user;

c) applying an ordering and annotation function for mapping the user context vector with the resource response set to generate an annotated response set having one or more annotations; and,

d) controlling the presentation of the resource response set to the user according to said annotations, wherein the ordering and annotation function is executed interactively at the time of each user query.

The District Court

Initially, IBM sued Zillow in the Western District of Washington for allegedly infringing five patents. The claims for two patents were dismissed, and Zillow filed a motion to dismiss under FRCP 12(b)(6) for the remaining three patents.

As for the ’676 patent, the district court found that the claims were merely directed to offering a user ‘the most beneficial and meaningful way’ to view the results of a query… and not advancing computer capabilities per se.”

The district court noted that four steps could be performed with a pen and paper, and that the claims were merely result-oriented.

Therefore, the district court found the asserted claims of the ’676 patent ineligible under §101.

As for the ’193 patent, the district court found that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of “more precisely tailoring the outcome of a query by guiding users (via icons, pull-down menus, dialogue boxes, and the like) to make choices about specific context variables, rather than requiring them to formulate and enter detailed search criteria.”

The district court did not find user context icons, separate workstations, and iterative navigation to be inventive concepts and held that they were well-understood, routine, or conventional at the time of the invention.

Therefore, the district court similarly found the asserted claims of the ’193 patent ineligible under §101.

The CAFC

The CAFC reviewed de novo.

As for the ’193 patent, the CAFC agreed with the district court that the claims do nothing more than improving a user’s experience while using a computer application.

Here, the CAFC noted that IBM failed to explain how the claims do anything more than identify, analyze, and present certain data to a user and that the claims did not disclose any technical improvement to how computer applications are used.

Furthermore, the CAFC agreed with the district court that IBM’s allegations of inventiveness “do[] not . . . concern the computer’s or graphical user interface’s capability or functionality, [but] relate[] merely to the user’s experience and satisfaction with the search process and results.”

Finally, the CAFC noted that the inventor declaration (“one of the key innovative aspects of the invention of the ’193 patent was not just the multiple visual workspaces alone, but how these various visual workspaces build upon each other and interact with each other,” as well as “the use of one visual workspace to affect the others in a closed-loop feedback system.”) did not cite the patent at all, and that neither the claims nor the specification include any such information. Therefore, the CAFC held that simply including allegations of inventiveness in a complaint with the inventor declaration did not make the complaint survive at the pleading stage.

Accordingly, the CAFC affirmed the district court’s decision holding that the ’193 patent is directed to ineligible subject matter under §101 and granting Zillow’s motion to dismiss as to the ’193 patent.

As for the ’676 patent, the CAFC agreed with the district court that the claims are directed to an abstract idea of displaying and organizing information because the representative claims use results-oriented language without mentioning any specific mechanism to perform the claimed steps.

In addition, the CAFC agreed with the district court that IBM failed to plausibly allege any inventive concept that would render the abstract claims patent-eligible.

IBM argued that the district court erred by failing to consider a supposed claim construction dispute regarding the term “user context vector”.

However, the CAFC noted that Zillow adapted IBM’s construction and did not propose an alternate construction. Therefore, the CAFC found that there was no claim construction dispute for the district court to resolve.

Accordingly, the CAFC affirmed the district court’s decision holding that the ’676 patent claimed ineligible subject matter under §101 and granting Zillow’s motion to dismiss as to the ’676 patent.

Dissenting opinion by Stoll

Stoll would vacate the district court’s holding of ineligibility of the claims of the ’676 patent because the majority, like the district court, did not meaningfully address IBM’s proposed construction of “user context vector.”

Takeaway:

- Conclusionary allegations of inventiveness in the inventor declaration would not help the patent to survive from patent eligibility attack in the pleading stage.

- The inventor declaration should be closely tied to the claims and the specification to help the patent to survive from patent eligibility attack.

Tags: 35 U.S.C. § 101 > declaration > Motion to Dismiss > patent eligible subject matter

MERE AUTOMATION OF MANUAL PROCESSES USING GENERIC COMPUTERS DOES NOT CONSTITUTE A PATENTABLE IMPROVEMENT IN COMPUTER TECHNOLOGY

| December 6, 2022

International Business Machines Corporation v. Zillow Group, Inc., Zillow, Inc.

Decided: October 17, 2022

Hughes (author), Reyna, and Stoll (dissenting in parts)

Summary:

In 2019, IBM sued Zillow for infringement of several patents related to graphical display technology in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington. Zillow filed a motion for judgment on the pleadings, arguing that the claims of IBM’s asserted patents were patent ineligible under § 101. The district court granted Zillow’s motion as to two IBM patents because they were directed to abstract ideas with no inventive concept. The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court decision and therefore, affirmed.

Details:

Two asserted IBM patents are U.S. Patent Nos. 9,158,789 (“the ’789 patent”) and 7,187,389 (“the ’389 patent”).

The ’789 patent

This patent describes a method for “coordinated geospatial, list-based and filter-based selection.” Here, a user draws a shape on a map to select that area of the map, and the claimed system then filters and displays data limited to that area of the map.

Claim 8 is a representative claim:

A method for coordinated geospatial and list-based mapping, the operations comprising:

presenting a map display on a display device, wherein the map display comprises elements within a viewing area of the map display, wherein the elements comprise geospatial characteristics, wherein the elements comprise selected and unselected elements;

presenting a list display on the display device, wherein the list display comprises a customizable list comprising the elements from the map display;

receiving a user input drawing a selection area in the viewing area of the map display, wherein the selection area is a user determined shape, wherein the selection area is smaller than the viewing area of the map display, wherein the viewing area comprises elements that are visible within the map display and are outside the selection area;

selecting any unselected elements within the selection area in response to the user input drawing the selection area and deselecting any selected elements outside the selection area in response to the user input drawing the selection area; and

synchronizing the map display and the list display to concurrently update the selection and deselection of the elements according to the user input, the selection and deselection occurring on both the map display and the list display.

The ’389 patent

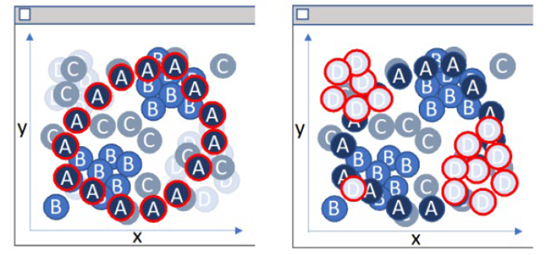

This patent describes methods of displaying layered data on a spatially oriented display based on nonspatial display attributes (i.e., displaying objects in visually distinct layers). Here, objects in layers of interest could be emphasized while other layers could be deemphasized.

Claim 1 is a representative claim:

A method of displaying layered data, said method comprising:

selecting one or more objects to be displayed in a plurality of layers;

identifying a plurality of non-spatially distinguishable display attributes, wherein one or more of the non-spatially distinguishable display attributes corresponds to each of the layers;

matching each of the objects to one of the layers;

applying the non-spatially distinguishable display attributes corresponding to the layer for each of the matched objects;

determining a layer order for the plurality of layers, wherein the layer order determines a display emphasis corresponding to the objects from the plurality of objects in the corresponding layers; and

displaying the objects with the applied non-spatially distinguishable display attributes based upon the determination, wherein the objects in a first layer from the plurality of layers are visually distinguished from the objects in the other plurality of layers based upon the non-spatially distinguishable display attributes of the first layer.

Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit reviewed the grant of a Rule 12 motion under the law of the regional circuit (de novo for the Ninth Circuit).

As for Alice step one analysis of the ’789 patent, the Federal Circuit held that the claims fail to recite any inventive technology for improving computers as tools, and instead directed to “an abstract idea for which computers are invoked merely as a tool.”

The Federal Circuit further held that identifying, analyzing, and presenting any data to a user is not an improvement specific to computer technology, and that mere automation of manual processes using generic computers is not a patentable improvement in computer technology.

The Federal Circuit held that this patent describes functions (presenting, receiving, selecting, synchronizing) without explaining how to accomplish these functions.

As for Alice step two analysis of the ’789 patent, the Federal Circuit noted that IBM has not made any allegations that any features of the claims is inventive. Instead, the Federal Circuit held that the limitations in this patent simply describe the abstract method without providing more.

As for Alice step one analysis of the ’389 patent, the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that this patent is directed to the abstract idea of organizing and displaying visual information (merely organize and arrange sets of visual information into layers and present the layers on a generic display device).

The Federal Circuit held that like the ’789 patent, this patent describes various functions without explaining how to accomplish any of them.

The Federal Circuit further held that the problem this patent tries to solve is not even specific to a computing environment, and the solution that this patent provides could be accomplished using colored pencils and translucent paper.

As for Alice step two analysis of the ’389 patent, the Federal Circuit noted that dynamic re-layering or rematching could also be done by hand (slowly), and that any of the patent’s improved efficiency does not come from an improvement in the computer but from applying the claimed abstract idea to a computer display.

Therefore, the Federal Circuit held that there is no inventive concept that transforms the abstract idea of organizing and displaying visual information into a patent-eligible application of that abstract idea.

Dissent by Stoll

Judge Stoll agreed with the majority opinion. However, she did not agree with the majority opinion that claims 9 and 13 of the ’389 patent are not patent eligible.

The information handling system as described in claim 8 further comprising:

a rearranging request received from a user;

rearranging logic to rearrange the displayed layers, the rearranging logic including:

re-matching logic to re-match one or more objects to a different layer from the plurality of layers;

application logic to apply the non-spatially distinguishable display attributes corresponding to the different layer to the one or more re-matched objects; and

display logic to display the one or more rematched objects.

She noted that in combination with factual allegations in the complaint (problems with the conventional technology with larger and complex data systems) and the expert declaration, the claimed relaying and rematching steps are directed to a technical improvement in how a user interacts with a computer with the GUI.

Takeaway:

- The argument that the claimed invention improves a user’s experience while using a generic computer is not sufficient to render the claims patent eligible at Alice step one analysis.

- Identifying, analyzing, and presenting certain data to a user is not an improvement specific to computing technology itself (mere automation of manual processes using generic computers not sufficient).

- The specification should be drafted to explain how to accomplish the required functions instead of merely describing them (avoid “result-based functional language”).

Tags: 35 U.S.C. §101 > Alice > patent eligible subject matter > patent ineligible subject matter

CLAIMS SHOULD PROVIDE SUFFICIENT SPECIFICITY TO IMPROVE THE UNDERLYING TECHNOLOGY

| September 30, 2021

Universal Secure Registry LLC, v. Apple Inc., Visa Inc., Visa U.S.A. Inc.

Before TARANTO, WALLACH, and STOLL, Circuit Judges. STOLL

Summary

The Federal Circuit upheld a decision that all claims of the asserted patents are directed to an abstract idea and that the claims contain no additional elements that transform them into a patent-eligible application of the abstract idea.

Background

USR sued Apple for allegedly infringing U.S. Patent Nos. 8,856,539; 8,577,813; 9,100,826; and 9,530,137 that are directed to secure payment technology for electronic payment transactions. The four patents involve different authentication technology to allow customers to make credit card transactions “without a magnetic-stripe reader and with a high degree of security.”

The magistrate judge determined that all the representative claims were not directed to an abstract idea. Particularly it was concluded that the claimed invention provided a more secure authentication system. The magistrate judge also explained that the non-abstract idea determination is based on that “the plain focus of the claims is on an improvement to computer functionality itself, not on economic or other tasks for which a computer is used in its ordinary capacity.” However, the district court judge disagreed and concluded that the asserted claims failed at both Alice steps and the claimed invention was directed to the abstract idea of “the secure verification of a person’s identity.” The district court explained that the patents did not disclose an inventive concept—including an improvement in computer functionality—that transformed the abstract idea into a patent-eligible application.

The Federal Circuit concluded that the asserted patents claim unpatentable subject matter and thus upheld the district court’s decision.

Discussion

The Federal Circuit addressed all asserted patents. The claims in the four patents have fared similarly. The discussion here is focused on the ‘137 patent. The ’137 patent is a continuation of the ’826 patent and discloses a system for authenticating the identities of users. Claim 12 is representative of the ’137 patent claims at issue, reciting

12. A system for authenticating a user for enabling a transaction, the system comprising:

a first device including:

a biometric sensor configured to capture a first biometric information of the user;

a first processor programmed to: 1) authenticate a user of the first device based on secret information, 2) retrieve or receive first biometric information of the user of the first device, 3) authenticate the user of the first device based on the first biometric, and 4) generate one or more signals including first authentication information, an indicator of biometric authentication of the user of the first device, and a time varying value; and

a first wireless transceiver coupled to the first processor and programmed to wirelessly transmit the one or more signals to a second device for processing;

wherein generating the one or more signals occurs responsive to valid authentication of the first biometric information; and

wherein the first processor is further programmed to receive an enablement signal indicating an approved transaction from the second device, wherein the enablement signal is provided from the second device based on acceptance of the indicator of biometric authentication and use of the first authentication information and use of second authentication information to enable the transaction.

Claim 12 recites a system for authenticating the identities of users, including a first device. The first device can include a biometric sensor, a first processor, and a first wireless transceiver, where the device utilizes authentication of a user’s identity to enable a transaction.

The district court emphasized that the claims recite, and the specification discloses, generic well-known components—“a device, a biometric sensor, a processor, and a transceiver—performing routine functions—retrieving, receiving, sending, authenticating—in a customary order.”

The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court and found that the claims of ‘137 patent include some limitations but still are not sufficiently specific. The Federal Circuit cited their previous decision, Solutran, Inc. v. Elavon, Inc (Fed. Cir. 2019) that held claims abstract “where the claims simply recite conventional actions in a generic way” without purporting to improve the underlying technology. The Court explained that claim 12 does not tell a person of ordinary skill what comprises the secret information, first authentication information, and second authentication information.

USR cited Finjan, Inc. v. Blue Coat Systems, Inc (Fed. Cir. 2018), arguing that the claim is akin to the claim in Finjan whose claims are directed to a method of providing computer security by scanning a downloadable file and attaching the scanned results to the downloadable file in the form of a “security profile.” However, the Court differentiated Finjan, explaining that Finjan employed a new kind of file enabling a computer system to do things it could not do before, namely “behavior-based” virus scans. In contrast, the claimed invention combines conventional authentication techniques to achieve an expected cumulative higher degree of authentication integrity. The claimed idea of using three or more conventional authentication techniques to achieve a higher degree of security is abstract without some unexpected result or improvement. The Court also acknowledged that some of the dependent claims provide more specificity on these aspects, but still concluded the claimed is still merely conventional and the specification discloses that each authentication technique is conventional.

The district court also turned to Alice step two to determine that claim 12 “lacks the inventive concept necessary to convert the claimed system into patentable subject matter.” USR asserted that the use of a time-varying value, a biometric authentication indicator, and authentication information that can be sent from the first device to the second device form an inventive concept. The Federal Circuit rejected this argument, explaining that the specification makes clear that each of these devices and functions is conventional because the patent acknowledged that the step of generating time-varying codes for authentication of a user is conventional and long-standing. USR further argued that authenticating a user at two locations constitutes an inventive concept because it is locating the authentication functionality at a specific, unconventional location within the network. However, the Court found that the specification of the patent suggests that the claims only recite a conventional location for the authentication functionality and thus rejected the argument. The court further stated that there is nothing in the specification suggesting, or any other factual basis for a plausible inference (as needed to avoid dismissal), that the combination of these conventional authentication techniques results in an unexpected improvement beyond the expected sum of the security benefits of each individual authentication technique.

The Federal Circuit ruled that all the patents simply described well-known and conventional ways to perform authentication and did not include any technological improvements that transformed those abstract ideas into patent-eligible inventions. The Court also cited several of its previous decisions related to patent invalidity under Alice, noting that “patent eligibility often turns on whether the claims provide sufficient specificity to constitute an improvement to computer functionality itself.”

Takeaway

- An abstract idea is not patentable if it does not provide an inventive solution to a problem in implementing the idea.

- Claims may be abstract even when they are directed to physical devices but include generic well-known components that perform conventional actions in a generic way without improving the underlying technology or only to achieve an expected cumulative improvement.

Anything Under §101 Can be Patent Ineligible Subject Matter

| August 16, 2021

Yanbin Yu, Zhongxuan Zhang v. Apple Inc., Fed. Cir. 2020-1760Yanbin Yu, Zhongxuan Zhang v. Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd., Samsung Electronics America, Inc., Fed. Cir. 2020-1803

Decided on June 11, 2021

Before Newman, Prost, and Taranto (Opinion by Prost, Dissenting opinion by Newman)

Summary

Yu had ’289 patent which is titled “Digital Cameras Using Multiple Sensors with Multiple Lenses” and sued Apple and Samsung at District Court for infringement. The District Court found that the ’289 patent is directed towards an abstract idea and does not include an inventive concept. The District Court held the patent was invalid under §101 and granted the defendant’s motion to dismiss. Yu appealed to the CAFC. The majority panel affirmed the District Court’s decision. However, Judge Newman dissented and wrote that the disputed patent is directed towards a mechanical and electronic device and not an abstract idea. The Judge also pointed out that neither the majority panel nor the District Court decided patentability under §102 or 103.

Details

Background

According to Yu, early digital camera technologies were starting to flourish in the 1990s. However, before the ’289 patent, “the technological limitations of then-existing image sensors—used as the capture mechanism—caused digital cameras to produce lower quality images compared with those produced by traditional film cameras.” The’289 patent was applied in 1999 and issued in 2003. Yu believed that “the ’289 patent solved the technological problems associated with prior digital cameras by providing an improved digital camera having multiple image sensors and multiple lenses.[1]” Yu also explained that “all dual-lens cameras on the market today use the techniques claimed in the ’289 Patent[2]” and therefore, sued Apple and Samsung (“the Defendants”) for infringement of claims 1, 2, and 4 of the ’289 patent in October 2018 (before the ’289 patent expires in 2019). In response, the Defendants filed a Rule 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss, asserting that the claims are directed towards an abstract idea under §101.

Claim 1 of the ’289 patent

1. An improved digital camera comprising:

a first and a second image sensor closely positioned with respect to a common plane, said second image sensor sensitive to a full region of visible color spectrum;

two lenses, each being mounted in front of one of said two image sensors;

said first image sensor producing a first image and said second image sensor producing a second image;

an analog-to-digital converting circuitry coupled to said first and said second image sensor and digitizing said first and said second intensity images to produce correspondingly a first digital image and a second digital image;

an image memory, coupled to said analog-to-digital converting circuitry, for storing said first digital image and said second digital image; and

a digital image processor, coupled to said image memory and receiving said first digital image and said second digital image, producing a resultant digital image from said first digital image enhanced with said second digital image.

The District Court held that the ’289 patent was directed to “the abstract idea of taking two pictures and using those pictures to enhance each other in some way” and “the asserted claims lack an inventive concept, noting “the complete absence of any facts showing that the claimed elements were not well-known, routine, and conventional.” Therefore, the District Court concluded that the ’289 patent was directed to an ineligible subject matter and entered judgment for Defendants. Yu appealed to the CAFC.

Majority Opinion

At the CAFC, as we have seen in the various other §101 precedents, the panel applied the two-step Mayo/Alice framework.

Step 1: “Whether a patent claim is directed to an unpatentable law of nature, natural phenomenon, or abstract idea. Alice, 573 U.S. at 217.”

Step 2: If Step 1 is Yes, “Whether the claim nonetheless includes an “inventive concept” sufficient to “‘transform the nature of the claim’ into a patent-eligible application. Id.”

(If Step 2’s answer is No, the invention is not a patent-eligible subject matter.)

In the majority opinion filed by Judge Prost, as to Step 1, the court applied the approach to the Step 1 inquiry “by asking what the patent asserts to be the focus of the claimed advance over the prior art” and concluded that “claim 1 is “directed to a result or effect that itself is the abstract idea and merely invoke[s] generic processes and machinery” rather than “a specific means or method that improves the relevant technology.” The majority opinion also mentioned that “Yu does not dispute that, as the district court observed, the idea and practice of using multiple pictures to enhance each other has been known by photographers for over a century.” The majority opinion also noted that although, “Yu’s claimed invention is couched as an improved machine (an “improved digital camera”), … “whether a device is “a tangible system (in § 101 terms, a ‘machine’)” is not dispositive”. Thus, the majority panel concluded that “the focus of claim 1 is the abstract idea.”

As to Step 2, the majority opinion concludes that claim 1 does not include an inventive concept sufficient to transform the claimed abstract idea into a patent-eligible invention because “claim 1 is recited at a high level of generality and merely invokes well-understood, routine, conventional components to apply the abstract idea” discussed in Step 1. Yu raised the prosecution history to prove that “the ’289 patent were allowed over multiple prior art references.” Also, Yu argued that the claimed limitations are “unconventional” because “the claimed “hardware configuration is vital to performing the claimed image enhancement.” However, the court was not convinced with this argument and conclude that “the claimedhardware configuration itself is not an advance and does not itself produce the asserted advance of enhancement of one image by another, which, as explained, is an abstract idea.”

Thus, the majority of the court concluded that the ‘’289 patent is not patent-eligible subject matter under §101. Therefore, the court hold for the Defendants.

Dissenting Opinion

In the dissenting opinion, Judge Newman said that “this camera is a mechanical and electronic device of defined structure and mechanism; it is not an “abstract idea” and “a statement of purpose or advantage does not convert a device into an abstract idea.”

The judge explained that “claim 1 is not for the general idea of enhancing camera image”, but “for a digital camera having a designated structure and mechanism that perform specified functions.” The Judge further mentioned, “the ‘abstract idea’ concept with respect to patent-eligibility is founded in the distinction between general principle and specific application.” The Judge quoted Diamond v. Chakrabarty and emphasized that “Congress intended statutory subject matter to ‘include anything under the sun that is made by man.’”

Judge Newman noted that “the ’289 patent may or may not ultimately satisfy all the substantive requirements of patentability”, and noted that neither the majority opinion and the district court discussed §102 and §103.

Takeaway

- After 7 years from Alice, we are still witnessing the profound impact that Alice has on §101 jurisprudence, and waiting for further judicial, legislative, and/or administrative clarity.

- In a previous §101 decision in American Axel (previously reported by John P. Kong), the dissenting opinion by Judges Chen and Wallach criticized that §101 swallowed §112. Now, Judge Newman criticized that §101 swallowed §102 and §103. The dire warning by the Supreme Court about §101 swallowing all of patent law seems to have come full circle.

- Judge Newman’s criticism of §101 swallowing §102 and §103 can be an added argument for appeal for another case and may help get these issues before the Supreme Court.

- John P. Kong said that The approach for determining the Step 1 inquiry, i.e., “by asking what the patent asserts to be the focus of the claimed advance over the prior art” is the source of much of the court’s criticisms. This approach was never vetted, and it conflates §101 with §102 and §103 issues. First, this “focus” is just another name for deriving the “point of novelty,” “gist,” “heart,” or “thrust” of the invention, which had previously been discredited by Supreme Court and Federal Circuit decisions relating to §102 and §103 issues. The problem with tests such as these is that it subtracts out various “conventional” features of the claimed invention (like what is done for the “claimed advance over the prior art”), and thus violates the Supreme Court requirement to consider the claim “as a whole.” If the point of novelty, gist, or heart of the invention contravenes the requirement to consider the claim “as a whole” in the §102 and §103 contexts, then it should likewise contravene the same Supreme Court requirement to consider the claim “as a whole” in the §101 context (as noted in John P. Kong’ “Today’s Problems with §101 and the Latest Federal Circuit Spin in American Axle v. Neapco” powerpoint, Dec. 2020). Judge Newman’s dissent echoes the same.

- John P. Kong also said that Enfish moved up into Step 1 the “improvement in technology” comment in Alice regarding the inventive concept consideration under Step 2 because some computer technology isn’t inherently abstract and thus should not be automatically subject to Alice’s Step 2 and its inventive-concept test. Enfish only had a passing reference to “inquiring into the focus of the claimed advance over the prior art” citing Genetic Techs v. Merial (Fed. Cir. 2016), as support for considering the “improvement in technology” in Alice Step 1. Herein lies the problem. The “improvement in technology” concept pertains to whether the claims are directed to a practical application, instead of an abstract idea. The “claimed advance over prior art” is not a substitute for, and not the same as, determining whether there is a practical application reflected in an improvement in technology. Stated differently, there can still be a practical application (and therefore not an abstract idea) even without checking the prior art and subtracting out “conventional” elements from the claim to discern a “claimed advance over the prior art.” While a positive answer to the “claimed advance over the prior art” would satisfy the “improvement in technology” point as being a practical application justifying eligibility, a negative answer to the “claimed advance over the prior art” does not diminish the claim being directed to a practical application (such as for an electric vehicle charging system, a garage door opener, a manufacturing method for a car’s driveshaft, or for a camera). But, in Electric Power Group v Alstom (Fed. Cir. 2016), the Fed. Cir. considered whether the “advance” is an abstract idea using a computer as a tool or a technological improvement in the computer or computer functionality (in an “improvement in technology” inquiry). And then, in Affinity Labs of Texas LLC v. DirecTV LLC, the Fed Cir cemented the “claimed advance” spin into Step 1, subtracting out “general components such as a cellular telephone, a graphical user interface, and a downloadable application” to arrive at a purely functional remainder that constituted an abstract idea of out-of-region delivery of broadcast content, without offering any technological means of effecting that concept (the 1-2 knockout of: subtract generic elements, and no “how-to” for the remainder). This laid the groundwork for §101 swallowing §§112, 102 and 103.

[1] See Brief, USDC ND of Ca Appeal Nos. 20-1760, -1803.

[2] See Yu v. Apple, United States District Court for the Northern District of California in No. 3:18-cv-06181-JD

Tailored Advertising Claims Are Invalidated Due to Lack of Improvements to Computer Functionality

| June 8, 2021

Free Stream Media Corp., DBA Samba Tv, V. Alphonso Inc., Ashish Chordia, Lampros Kalampoukas, Raghu Kodige

Decided on May 11, 2021

Before DYK, REYNA, and HUGHES. Opinion by REYNA.

Summary

The Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s decision and found that the asserted claims directed to tailored advertising were patent ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

Background

Free Stream sued Alphonso for infringement of its US patents No. 9,026,668 (“the ’668 patent”) and No. 9,386,356 (“the ’356 patent”). The patents describe a system sending tailored advertisements to a mobile phone user based on data gathered from the user’s television. Claim 1 and 10 were involved in the alleged infringement. Free Stream conceded claims 1 and 10 are similar. Listed below is claim 1.

1. A system comprising:

a television to generate a fingerprint data;

a relevancy-matching server to:

match primary data generated from the fingerprint data with targeted data, based on a relevancy factor, and

search a storage for the targeted data;

wherein the primary data is any one of a content identification data and a content identification history;

a mobile device capable of being associated with the television to:

process an embedded object,

constrain an executable environment in a security sandbox, and

execute a sandboxed application in the executable environment; and

a content identification server to:

process the fingerprint data from the television, and

communicate the primary data from the fingerprint data to any of a number of devices with an access to an identification data of at least one of the television and an automatic content identification service of the television.

The asserted claims of ‘356 patent includes three main components: (1) a television (e.g., a smart TV) or a networked device ; (2) a mobile device or a client device ; and (3) a relevancy matching server and a content identification server. The television is a network device collecting primary data, which can consist of program information, location, weather information, or identification information. The mobile phone is a client device that may be smartphones, computers, or other hardware showing advertisements. The client device includes a security sandbox, which is a security mechanism for separating running programs. Finally, the servers use primary data from the networked device to select advertisements or other targeted data based on a relevancy factor associated with the user.

Alphonso argued that the asserted claims are patent ineligible under § 101 because they are directed to the abstract idea of tailored advertising. But Free Stream characterized the claims as directed to a specific improvement of delivering relevant content (e.g., targeted advertising) by bypassing the conventional “security sandbox” separating the mobile phone from the television.

The district court rejected Alphonso’s argument and applied step one of the Alice test to conclude that the asserted claims are not directed to an abstract idea. The district court found that the ’356 patent “describes systems and methods for addressing barriers to certain types of information exchange between various technological devices, e.g., a television and a smartphone or tablet being used in the same place at the same time.”

Discussion

The Federal Circuit agreed with Alphonso’s contention that the district court erred in concluding that the ’356 patent is not directed to patent-ineligible subject matter. Claims 1 and 10 were reviewed by the Federal Circuit as being directed to (1) gathering information about television users’ viewing habits; (2) matching the information with other content (i.e., targeted advertisements) based on relevancy to the television viewer; and (3) sending that content to a second device.

Free Stream contended that claim 1 is “specifically directed to a system wherein a television and a mobile device are intermediated by a content identification server and relevancy-matching server that can deliver to a ‘sandboxed’ mobile device targeted data based on content known to have been displayed on the television, despite the barriers to communication imposed by the sandbox.” Free Stream also asserted that its invention allows devices on the same network to communicate where such devices were previously unable to do so, namely bypassing the sandbox security.

The Federal Circuit, however, noted that the specification does not provide for any other mechanism that can be used to bypass the security sandbox other than “through a cross site scripting technique, an appended header, a same origin policy exception, and/or an other mode of bypassing

a number of access controls of the security sandbox.” Also, the Federal Circuit pointed out that the asserted claims only state the mechanism used to achieve the bypassing communication but not at all describe how that result is achieved.

Further, the Federal Circuit went on to note that “even assuming the specification sufficiently discloses how the sandbox is overcome, the asserted claims nonetheless do not recite an improvement in computer functionality.” The asserted claims do not incorporate any such limitations of bypassing the sandbox. The Federal Circuit determined that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of “targeted advertising.”

The Federal Circuit further reached Step 2 because the district court concluded that the claims were not directed to an abstract idea at Step 1. Free Stream argued that the claims of the ’356 patent “specify the components or methods that permit the television and mobile device to operate in [an] unconventional manner, including the use of fingerprinting, a content identification server, a relevancy-matching server, and bypassing the mobile device security sandbox.”

The argument on Step 2 was also directed around bypassing sandbox security. The Federal Circuit explained that the security sandbox may limit access to the network, but the claimed invention simply seeks to undo that by “working around the existing constraints of the conventional functioning of television and mobile devices.” It was concluded that “such a ‘work around’ or ‘bypassing’ of a client device’s sandbox security does nothing more than describe the abstract idea of providing targeted content to a client device.” The Federal Circuit emphasized that “an abstract idea is not patentable if it does not provide an inventive solution to a problem in implementing the idea.” Finally, the Federal Circuit found that the asserted claims simply utilized generic computing components arranged in a conventional manner but failed to embody an “inventive solution to a problem.”

Takeaway

- An abstract idea is not patentable if it does not provide an inventive solution to a problem in implementing the idea.

- The “work-around” does not add more features that give rise to a Step 2 “inventive concept.”

An Improvement in Computational Accuracy Is Not a Technological Improvement

| May 20, 2021

In Re: Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University

Decided on March 25, 2021

Prost, Lourie and Reyna. Opinion by Reyna.

Summary:

This case is an appeal from a PTAB decision that affirmed the Examiner’s rejection of the claims on the grounds that they involve patent ineligible subject matter. Leland Stanford Junior University’s patent to computerized statistical methods for determining haplotype phase were held by the CAFC to be to an abstract idea directed to the use of mathematical calculations and statistical modeling and that the claims lack an inventive concept that transforms the abstract idea into patent eligible subject matter. Thus, the CAFC affirmed the rejection on the grounds that the claims are to patent ineligible subject matter.

Details:

Leland Stanford Junior University’s (“Stanford”) patent application is to methods for determining haplotype phase which provides an indication of the parent from whom a gene has been inherited. The application discloses methods for inferring haplotype phase in a collection of unrelated individuals. The methods involve using a statistical tool called a hidden Markov model (“HMM”). The application uses a statistical model called PHASE-EM which allegedly operates more efficiently and accurately than the prior art PHASE model. The PHASE-EM uses a particular algorithm to predict haplotype phase.

Representative claim 1 recites:

1. A computerized method for inferring haplotype phase in a collection of unrelated individuals, comprising:

receiving genotype data describing human genotypes for a plurality of individuals and storing the genotype data on a memory of a computer system;

imputing an initial haplotype phase for each individual in the plurality of individuals based on a statistical model and storing the initial haplotype phase for each individual in the plurality of individuals on a computer system comprising a processor a memory;

building a data structure describing a Hidden Markov Model, where the data structure contains:

a set of imputed haplotype phases comprising the imputed initial haplotype phases for each individual in the plurality of individuals;

a set of parameters comprising local recombination rates and mutation rates;

wherein any change to the set of imputed haplotype phases contained within the data structure automatically results in re-computation of the set of parameters comprising local recombination rates and mutation rates contained within the data structure;

repeatedly randomly modifying at least one of the imputed initial haplotype phases in the set of imputed haplotype phases to automatically re-compute a new set of parameters comprising local recombination rates and mutation rates that are stored within the data structure;

automatically replacing an imputed haplotype phase for an individual with a randomly modified haplotype phase within the data structure, when the new set of parameters indicate that the randomly modified haplotype phase is more likely than an existing imputed haplotype phase;

extracting at least one final predicted haplotype phase from the data structure as a phased haplotype for an individual; and

storing the at least one final predicted haplotype phase for the individual on a memory of a computer system.

The PTAB determined that the claim describes receiving genotype data followed by mathematical operations of building a data structure describing an HMM and randomly modifying at least one imputed haplotype to automatically recompute the HMM’s parameters. Thus, the PTAB held that the claim is to patent ineligible abstract ideas such as mathematical relationships, formulas, equations and calculations. The PTAB further found that the additional elements in the claim recite generic steps of receiving and storing genotype data in a computer memory, extracting the predicted haplotype phase from the data structure, and storing it in a computer memory, and that these steps are well-known, routine and conventional. Thus, finding the claim ineligible under steps one and two of Alice, the PTAB affirmed the Examiner’s rejection as being to ineligible subject matter.

On appeal, the CAFC followed the two-step test under Alice for determining patent eligibility.

1. Determine whether the claims at issue are directed to a patent-ineligible concept such as laws of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract ideas. If so, proceed to step 2.

2. Examine the elements of each claim both individually and as an ordered combination to determine whether the claim contains an inventive concept sufficient to transform the nature of the claims into a patent-eligible application. If the claim elements involve well-understood, routine and conventional activity they do not constitute an inventive concept.

Under step one, the CAFC found that the claims are directed to abstract ideas including mathematical calculations and statistical modeling. Citing Parker v. Flook, 437 U.S. 584, 595 (1978), the CAFC stated that mathematical algorithms for performing calculations, without more, are patent ineligible under § 101. The CAFC determined that claim 1 involves “building a data structure describing an HMM,” and then “repeatedly randomly modifying at least one of the imputed haplotype phases” to automatically recompute parameters of the HMM until the parameters indicate that the most likely haplotype is found. The CAFC also found that the steps of receiving genotype data, imputing an initial haplotype phase, extracting the final predicted haplotype phase from the data structure, and storing it in a computer memory do not change claim 1 from an abstract idea to a practical application. The CAFC concluded that “Claim 1 recites no application, concrete or otherwise, beyond storing the haplotype phase.”

Stanford argued that the claim provides an improvement of a technological process because the claimed invention provides greater efficiency in computing haplotype phase. However, the CAFC stated that this argument was forfeited because it was not raised before the PTAB.

Stanford also argued that the claimed invention provides an improvement in the accuracy of haplotype predictions rendering claim 1 a practical application rather than an abstract idea. However, the CAFC stated that “the improvement in computational accuracy alleged here does not qualify as an improvement to a technological process; rather, it is merely an enhancement to the abstract mathematical calculation of haplotype phase itself.” The CAFC concluded that “[t]he different use of a mathematical calculation, even one that yields different or better results, does not render patent eligible subject matter.”

Under step two, the CAFC determined that there is no inventive concept that would transform the use of the claimed algorithms and mathematical calculations from an abstract idea to patent eligible subject matter. The steps of receiving, extracting and storing data are well-known, routine and conventional steps taken when executing a mathematical algorithm on a regular computer. The CAFC further stated that claim 1 does not require or result in a specialized computer or a computer with a specialized memory or processor.

Stanford argued that the PTAB failed to consider all the elements of claim 1 as an ordered combination. Specifically, they stated that it is the specific combination of steps in claim 1 “that makes the process novel” and “that provides the increased accuracy over other methods.” The CAFC did not agree stating that the PTAB was correct in its determination that claim 1 merely “appends the abstract calculations to the well-understood, routine, and conventional steps of receiving and storing data in a computer memory and extracting a predicted haplotype.” The CAFC further stated that even if a specific or different combination of mathematical steps yields more accurate haplotype predictions than previously achievable under the prior art, that is not enough to transform the abstract idea in claim 1 into a patent eligible application.

Comments

A key point from this case is that an improvement in computational accuracy does not qualify as an improvement to a technological process. It is merely considered an enhancement to an abstract mathematical calculation. Also, it seems that Stanford made a mistake by not arguing at the PTAB that the claimed invention provides the technological advance of greater efficiency in computing haplotype phase. The CAFC considered this argument forfeited. It is not clear if this argument would have saved Stanford’s patent application, but it certainly would have helped their case.

CAFC finds broadly claimed computer memory system eligible under first step of Alice.

| September 21, 2017

Visual Memory LLC v Nvidia Corporation

August 15, 2017

Before O’Malley, Hughes and Stoll. Precedential Opinion by Stoll, joined by O’Malley; Dissent by Hughes.

Summary:

Visual Memory sued Nvidia for infringement of USP 5,953,740 (the ‘740 patent). The district court granted Nvidia’s motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim (rule 12(b)(6)) based on patent ineligible subject matter. The CAFC reversed and remanded finding that the computer memory systems claims of the ‘740 satisfied the first step of Alice.

Tags: 35 U.S.C. § 101 > Alice > patent eligible subject matter > patent ineligible subject matter

Last month on §101: You Win Some (Amdocs), You Lose Some (FairWarning; Synopsys)

| November 21, 2016

Amdocs (Israel) Limited v. Openet Telecom, Inc.

November 1, 2016

Before Newman, Plager, and Reyna. Opinion by Plager. Dissenting opinion by Reyna.

Summary

A trio of Federal Circuit decisions on patent eligible subject matter in the past month offers additional guidance on how to survive scrutiny under 35 U.S.C. §101. The focus will be on Amdocs (Israel) Limited v. Openet Telecom, Inc., in which the Federal Circuit found eligibility, but for the sake of comparison, the Federal Circuit’s decisions in FairWarning IP, LLC v. Iatric Systems, Inc. and Synopsys, Inc. v. Mentor Graphics Corporation, in which the Federal Circuit reached the opposite conclusion, will be briefly summarized.

Tangible Components in the Claims could not save from 12(b)(6)Dismissal for patent-ineligible subject matter after Alice

| June 6, 2016

TLI Communications LLC v. AV Automotive et al.

May 17, 2016

Before Dyk, Schall and Hughes. Opinion by Hughes.

Summary

The East-District of Virginia dismissed the patent infringement suit under FRCP 12(B)(6) on the basis that the claims did not contain patent-eligible subject matter. TLI appealed to the CAFC. The Court, relying heavily on the disclosures of the patent’s specification, affirmed the ruling noting that the tangible components in the claims were insufficient to survive the Alice test even without a finding of fact.

Tags: 35 U.S.C. Section 101 > Motion to Dismiss > patent eligible subject matter

Inventive concept standing alone is not patent eligible

| July 10, 2015

Internet Patents Corp. v. Active Network, Inc.,

June 23, 2015

Before: Newman (Opinion author), Moore and Reyna.

Summary

Claims to a method which allows the use of a conventional web browser Back and Forward button functions without loss of data were not patent eligible under 35 U.S.C. 101 because the inventive concept recited in the claim was not limited to any mechanism and thus remained abstract.

Tags: 35 U.S.C. § 101 > abstract ideas > inventive concept > patent eligible subject matter > significantly more