Should’ve, Could’ve, Would’ve; Hindsight is as common as CDMA, allegedly!

| March 5, 2020

Acoustic Technology, Inc., vs., Itron Networked Solutions, In.

February 13, 2020

Circuit Judges Moore, Reyna (author) and Taranto.

Summary:

i. Background:

Acoustic owns U.S. Patent No., 6,509,841 (‘841 hereon), which relates to communications systems for utility providers to remotely monitor groups of electricity meters.

Back in 2010, Acoustic sued Itron for infringement of the ‘841 patent, with the parties later settling. As part of this settlement, Acoustic licensed the patent to Itron. As a result of the lawsuit, Itron was time-barrred from seeking inter partes review (IPR), of the patent. See 35 U.S.C. § 315(b).

Six years later, Acoustic sued Silver Spring Networks, Inc., (SS) for infringement, and in response, SS filed an IPR petition that has given rise to this Appeal.

Prior to and thereafter filing the IPR, SS was in discussions with Itron regarding a potential merger. Nine days after the Board instituted IPR, the parties agreed to merge. It was publicly announced the following day. The merger was completed while the IPR proceeding remained underway. SS filed the necessary notices that listed Itron as a real-party-in-interest.

Finally, seven months after Itron and SS completed the merger, the Board entered a final written decision wherein they found claim 8 of the ‘841 patent unpatentable. Acoustic did not raise a time-bar challenge to the Board.

ii. Appeal Issues:

ii-a: Acoustic alleges the Boards final written decision should be vacated because the underlying IPR proceeding is time-barred under 35 U.S.C. § 315(b).

ii.b: Acoustic alleges the Boards unpatentability findings are unsupported.

iii. IPR

35 U.S.C. § 315(b)

An inter partes review may not be instituted if the petition requesting the proceeding is filed more than 1 year after the date on which the petitioner, real party in interest, or privy of the petitioner is served with a complaint alleging infringement of the patent.

The CAFC held that “when a party raises arguments on appeal that it did not raise to the Board, they deprive the court of the benefit of the Board’s informed judgment.” Thus, since Acoustic failed to raise this issue to the Board, the CAFC declined to resolve whether Itron’s pre-merger activities rendered it a real-party-in-interest. Concluding, the CAFC stated that “[A]lthough we do not address the merits of Acoustic’s time-bar argument, we note Acoustics concerns about the concealed involvement of interested, time-barred parties.”

iv. Unpatentability

The sole claim at issue is as follows:

8. A system for remote two-way meter reading comprising:

a metering device comprising means for measuring usage and for transmitting data associated with said measured usage in response to receiving a read command;

a control for transmitting said read command to said metering device and for receiving said data associated with said measured usage transmitted from said metering device; and

a relay for code-division multiple access (CDMA) communication between said metering device and said control, wherein said data associated with said measured usage and said read command is relayed between said control and metering device by being passed through said relay.

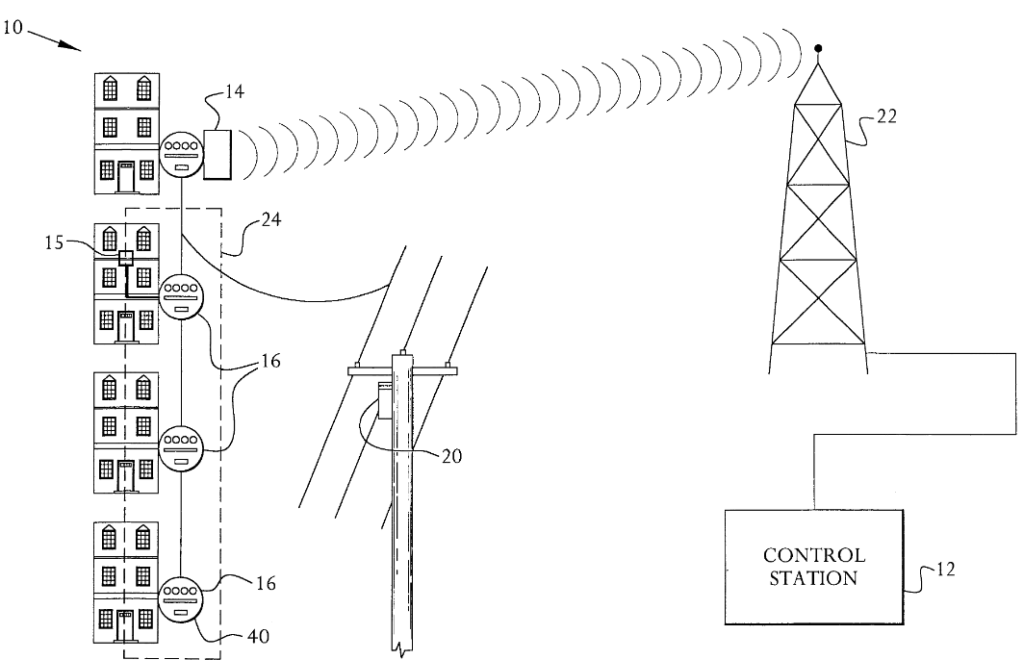

Fig. 1:

Key: 16 = on-site utility meters: 14 = relay means: 12 = contro means. The relay means can communicate via CMDA (code-divisional mutliple access), which is descibred as “an improvement upon prior art automated meter reading systems that used exspensive and problematic radio frrequency transmitter or human meter-readers.”

- Novelty

The CAFC upheld both anticipation challenges.

The first, anticipation by Netcomm, Acoustic claims that the Board erred by finding the reference disclosed the claimed CDMA communication limitation. Acoustic argued that the Board based its final decision entirely upon SS’s expert Dr. Soliman, who applied an incorrect standard. Specifically, that Dr. Soliman’s statements used the word “recognize” which, Acoustic alleged, was akin to testimony about what a prior art reference “suggests”, and so goes to obvious not anticipation. CAFC disagreed with Acoustic.

CAFC held that the “question is whether a skilled artisan would “reasonably understand or infer” from a prior art reference that every claim limitation is disclosed in that single reference.” Further that, “Expert testimony may shed light on what a skilled artisan would reasonably understand or infer from a prior art reference,” and “expert testimony can constitute substantial evidence of anticipation when the expert explains in detail how each claim element is disclosed in the prior art reference.”

The CAFC held that “Dr. Soliman conducted a detailed analysis and explained how a skilled artisan would reasonably understand that NetComm’s disclosure of radio wave communication was the same as CDMA,” and “Acoustic provided no evidence to rebut Dr. Soliman’s testimony.”

The second, anticipation by Gastouniotis, Acoustic argued that “the Board’s finding is erroneous because the Board relied on “the same structures to satisfy separate claim limitations.” Specifically, Acoustic asserts that the Board relied on the same “remote station 6” in Gastouniotis to satisfy the “control” and “relay” limitations of claim 8.” CAFC disagreed with Acoustic.

Specifically, the CAFC held that Gastouniotis disclosed a system that included a plurality of “remote stations” and “that individual “remote stations” may have different functions in a given embodiment.” So, “In finding that Gastouniotis anticipated claim 8, the Board relied on separate “remote station” structures to meet the “control” and “relay” limitations.” Again, the CAFC held that “Dr. Soliman provided unrebutted testimony that a skilled artisan would understand that these remote stations disclosed in Gastouniotis” meet the limitations of claim 8.

- Obviousness

Acoustic challenged the Boards determination of obvious in view of Nelson and Roach. “Acoustic asserts two errors in the Board’s obviousness analysis: (i) that the Board erroneously mapped Nelson onto the elements of claim 8; and (ii) that the Board’s motivation-to-combine finding is not supported by substantial evidence.” The CAFC rejected both arguments.

Regarding point (i): “Acoustic asserts that the Board relied on the same “electronic meter reader (EMR)” in Nelson to satisfy both the “metering device” and “relay” limitations of claim 8.” Again, the CAFC held that the Board had correctly relied on “separate EMR structures to meet the “metering device” and “relay” limitations,” and that “Dr. Soliman provided unrebutted testimony that a skilled artisan would recognize” the metering apparatus of Nelson as meeting the limitations of claim 8.”

Regarding point (ii): “Acoustic requests that [the CAFC] reverse the Board’s finding because the Board relied on “attorney argument,” and “generically cited to [Dr. Soliman’s] expert testimony.” The CAFC held that “The motivation to combine prior art references can come from the knowledge of those skilled in the art, from the prior art reference itself, or from the nature of the problem to be solved.” That, the CAFC “have found expert testimony insufficient where, for example, the testimony consisted of conclusory statements that a skilled artisan could combine the references, not that they would have been motivated to do so.”

However, ultimately, the CAFC found that “Dr. Soliman’s testimony was not conclusory or otherwise defective, and the Board was within its discretion to give that testimony dispositive weight.” That the Board did not merely “generically” cite to Dr. Soliman’s testimony, but cited specific pages. Thus concluding that the “expert testimony constituted substantial evidence of a motivation to combine prior art references.”

Additional Note:

The subject ‘841 Patent is a continuation of U.S. Patent Application No., 08/949,440 (Patent No., 5,986,574). Acoustic filed a related appeal in said Patent on the same day as filing this Appeal. (Acoustic Tech., Inc. v. Itron Networked Solutions, Inc., Case No. 2019-1059). Oral arguments were heard in both cases on the same day, and the CAFC simultaneously issued opinions in both cases.

In the related Appeal, Acoustics argued again that the CAFC “must vacate the Board’s final written decisions because the inter partes reviews were time-barred under 35 U.S.C. § 315(b).” For the same reasons outlined above, Acoustics were unsuccessful.

The second issue on Appeal in the related case centered on Acoustic arguing that the CAFC “should reverse the Board’s obviousness findings on grounds that the Board erroneously construed the “WAN means” term.” However, the CAFC noted that “Acoustic’s argument on appeal is new. Rather than arguing that the prior art fails to disclose a conventional radio capable of transmitting over publicly available WAN, Acoustic now argues that the prior art fails to disclose any conventional WAN radio” Thus, “[B]ecause Acoustic never presented to the Board the non-obviousness arguments it now raises on appeal, we find those arguments waived,” and so the Board’s decision was affirmed.

Take-away:

1. Ensure all arguments are presented to the Board.

2. Ensure that any arguments against an unpatentability rejection directly address the actual reasons for rejection. That is, the CAFC repeatedly stated that Acoustic had failed to rebut any of the actual reasons outlined in the expert testimony that the Board ultimately relied upon in its holding.

3. Be aware of Broadest Reasonable Interpretation. Here, Acoustic argued

What role does inherency have in an obviousness analysis?

| February 22, 2020

Persion Pharmaceuticals LLC v. Alvogen Malta Operations Ltd.

December 27, 2019

Before O’Malley, Reyna, and Chen (Opinion by Reyna).

Summary

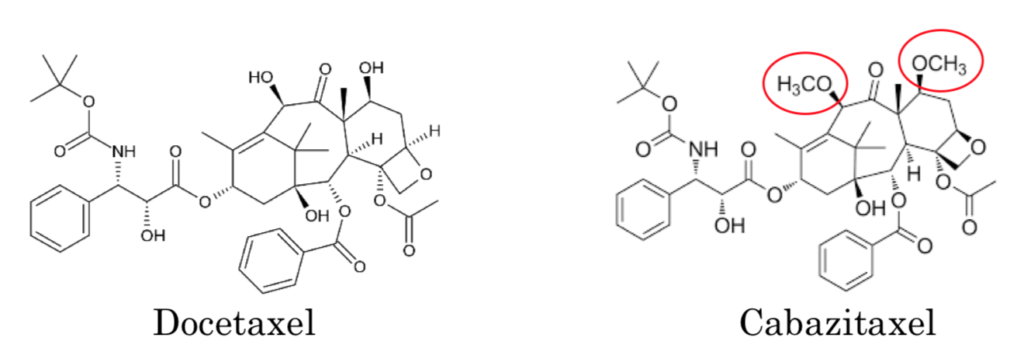

The Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision invalidating as obvious patents directed to method of using a hydrocodone-only formulation to treat pain in patients with hepatic impairment. Important to the obviousness determination was the concept of “inherency”. Specifically, the Federal Circuit agreed with the District Court that where the claimed method of would have been obvious from the prior art, claim limitations directed to the pharmacokinetic properties of the formulation would be inherent in the combination of the prior art.

Details

Hydrocodone is an opioid pain medication commonly prescribed to treat prolonged, severe pain. The bulk of metabolism of many opioids, including hydrocodone, occurs in the liver. People suffering from hepatic impairment (i.e., liver dysfunction) are at increased risk of opioid overdose, because their livers cannot clear the drugs from their bloodstreams as quickly and effectively as would be the case for people with healthy livers. As such, when prescribed to patients with impaired livers, dosages of opioids are often adjusted to prevent build-ups.

Persion Pharmaceuticals, LLC (“Persion”) commercializes a hydrocodone drug under the brand name Zohydro ER. The drug is an extended-released hydrocodone-only product—that is, it contains no other active ingredients. Clinical trials on Zohydro ER revealed, to its inventors’ surprise, that the concentration of hydrocodone in the bloodstream of subjects with mild and moderate hepatic impairment was not dramatically higher than in patients with unimpaired livers. The inventors of Zohydro ER filed U.S. patent applications that eventually issued as U.S. Patent Nos. 9,265,760 (“760 patent”) and 9,339,499 (“499 patent”).

The 760 and 499 patents were directed specifically to methods of treating pains in patients with mild or moderate hepatic impairment, and the claims emphasized the similar effects that the hydrocodone-only formulation had on patients with and without hepatic impairment.

The relevant claims of the two patents fell into two categories. The “non-adjustment” claims recited the lack of need to adjust the dosage for patients with mild or moderate hepatic impairment relative to patients without hepatic impairment. Meanwhile, the “pharmacokinetic” claims recited certain pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters that highlighted the similarity in the results of administering the claimed formulation to patients with and without hepatic impairment.

Claim 1 of the 760 patent is representative of the “non-adjustment” claims:

1. A method of treating pain in a patient having mild or moderate hepatic impairment, the method comprising:

administering to the patient having mild or moderate hepatic impairment a starting dose of an oral dosage unit having hydrocodone bitartrate as the only active ingredient, wherein the dosage unit comprises an extended release formulation of hydrocodone bitartrate, and wherein the starting dose is not adjusted relative to a patient without hepatic impairment.

Claim 12 of the 760 patent is representative of the “pharmacokinetic” claims:

12. A method of treating pain in a patient having mild or moderate hepatic impairment, the method comprising:

administering to the patient having mild or moderate hepatic impairment an oral dosage unit having hydrocodone bitartrate as the only active ingredient, wherein the dosage unit comprises an extended release formulation of hydrocodone bitartrate,

wherein the dosage unit provides a release profile of hydrocodone that:

(1) does not increase average hydrocodone AUC0-inf in subjects suffering from mild hepatic impairment relative to subjects not suffering from renal or hepatic impairment in an amount of more than 14%;

(2) does not increase average hydrocodone AUC0-inf in subjects suffering from moderate hepatic impairment relative to subjects not suffering from renal or hepatic impairment in an amount of more than 30%;

(3) does not increase average hydrocodone Cmax in subjects suffering from mild hepatic impairment relative to subjects not suffering from renal or hepatic impairment in an amount of more than 9%; and

(4) does not increase average hydrocodone Cmax in subjects suffering from moderate hepatic impairment relative to subjects not suffering from renal or hepatic impairment in an amount of more than 14%.

When Alvogen Malta Operations, Ltd. (“Alvogen”) filed an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) seeking to market a generic version of Zohydro ER, Persion sued Alvogen for infringing the 760 and 499 patents.

Naturally, Alvogen sought to invalidate those patents.

The prior art at issue were Devane (US2006/0240105), Jain (US2010/0010030), Vicodin label, and Lortab label.

Devane disclosed the same formulation as Zohydro ER, and disclosed an in vivo study in which the formulation was administered to treat post-operative pains in patients following their bunionectomy surgery. Devane did not disclose patients with mild or moderate hepatic impairment.

Jain disclosed a hepatic impairment PK study on Vicodin CR, a hydrocodone-acetaminophen combination formulation. Jain reported that the PK parameters (Cmax and AUC values) for hydrocodone in Vicodin CR were similar in normal and hepatically impaired subjects.

The Vicodin and Lortab labels disclosed the dosing instructions for those drugs. Vicodin contains hydrocodone and acetaminophen. Lortab contains hydrocodone and ibruprofen. The labels did not provide any precautions or dosing restrictions for individuals with mild or moderate hepatic impairment.

The district court found that the claims were obvious over the cited prior art.

As to the “non-adjustment” claims, the district court found that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have been motivated to administer Devane’s formulation to patients with mild or moderate hepatic impairment, because Jain taught that the hydrocodone exhibited similar PK parameters in normal and hepatically impaired patients, while the Vicodin and Lortab labels did not require different dosages for patients with mild or moderate hepatic impairment.

As to the “pharmacokinetic” claims, the district court found that the claimed PK values were “inherent in any obviousness combination that contains the Devane formulation”, because Devane disclosed what was essentially Zohydro ER, i.e., the claimed formulation, and the claimed values were “necessarily present” in Zohydro ER.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit honed in on Persion’s challenge of the district court’s “inherency” determination. Persion argued that Devane did not teach administering its formulation to hepatically impaired patients, so that “the natural result flowing from the operation as taught” in Devane could not be the claimed pharmacokinetic properties.

The Federal Circuit disagreed, distinguishing between the applications of “inherency” in the obviousness and anticipation contexts:

To the extent Persion contends that inherency can only satisfy a claim limitation when all other limitations are taught in a single reference, that position is contrary to our prior recognition that “inherency may supply a missing claim limitation in an obviousness analysis” where the limitation at issue is “the natural result of the combination of prior art elements.”

As the Federal Circuit noted, the longstanding rule is that “an obvious formulation cannot become nonobvious simply by administering it to a patient and claiming the resulting serum concentrations.”

Notably, there was no dispute that if administered under the same conditions, Devane’s formulation, which was identical to Zohydro ER, would necessarily exhibit the claimed PK values.

Related was Persion’s argument that the person skilled in the art would not have combined the cited prior art as the district court had. In particular, Persion argued that the district court should not have relied on the combination formulations disclosed in Jain and the Vicodin and Lortab labels.

Here also, the Federal Circuit disagreed. The Federal Circuit focused primarily on Jain’s teachings that its hydrocodone-acetaminophen combination formulation produced similar PK results for normal and hepatically impaired patients. That is, if Jain disclosed that its combination formulation was safe for patients with hepatic impairment, then it would be reasonable to expect the acetaminophen-free, hydrocodone-only formulation to be even safer. Further, considering Jain’s reported similarity in PK results for both hepatically impaired and unimpaired patients, it would have been obvious to the person skilled in the art to forgo dose adjustments when administering the same hydrocodone formulation to patients with hepatic impairment.

Where a claim defines some property of the claimed invention, it is not uncommon to find Examiners relying on inherency for those properties to complete their obviousness analyses. Reliance may be especially prevalent in chemical arts, as it has long been established that a chemical composition and its properties are inseparable. The Persion decision seems to reinforce the idea of inherency as a powerful argument that allows a missing limitation to be supplied based on some hypothetical combination of the prior art. That said, I suspect that the reach of the Persion decision will limited, as the fact that Persion’s claimed hydrocodone formulation already existed may have made it easier for the Federal Circuit to accept the finding of inherency.

Takeaway

- If the claim is directed to a new use of a known compound, then the claim should be more specific than a single, generic step of “applying the compound”. Consider defining the specific population or subpopulation that is helped by the compound, the specific conditions under which the compound is applied, and/or combination of the compound with other ingredients.

- If one can help it, avoid reciting intended results, which continue to be a complicated strategy. Not only could such a recitation force the issue of inherency, it could also raise the question of whether the recitation is even entitled to patentable weight, which is often a difficult argument to win with Examiners.

GENERAL KNOWLEDGE OF A SKILLED ARTISAN COULD BE USED TO SUPPLY A MISSING CLAIM LIMITATION FROM THE PRIOR ART WITH EXPERT EVIDENCE IN THE OBVIOUSNESS ANALYSIS

| February 5, 2020

Koninklijke Philips N.V. v. Google LLC, Microsoft Corporation, Microsoft Mobile Inc.

January 30, 2020

Summary:

The Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s final decision that claims of Philips’ ‘806 patent are unpatentable as obvious. The Federal Circuit held that the PTAB did not err in relying on general knowledge to supply a missing claim limitation in the IPR if the PTAB relied on expert evidence corroborated by a cited reference. The Federal Circuit also held that the PTAB did not have discretion to institute the IPR on the grounds not advanced in the petition.

Details:

The ‘806 Patent

Philips’ ‘806 patent is directed to solving a conventional problem where the user cannot play back the digital content until after the entire file has finished downloading. Also, the ‘806 patent states that streaming requires “two-way intelligence” and “a high level of integration between client and server software,” thereby excluding third parties from developing software and applications.

The ‘806 patent offers a solution that reduces delay by allowing the media player download the next portion of a media presentation concurrently with playback of the previous portion.

Representative claim 1 of the ‘806 patent:

1. A method of, at a client device, forming a media presentation from multiple related files, including a control information file, stored on one or more server computers within a computer network, the method comprising acts of:

downloading the control information file to the client device;

the client device parsing the control information file; and based on parsing of the control information file, the client device:

identifying multiple alternative flies corresponding to a given segment of the media presentation,

determining which files of the multiple alternative files to retrieve based on system restraints;

retrieving the determined file of the multiple alternative files to begin a media presentation,

wherein if the determined file is one of a plurality of files required for the media presentation, the method further comprises acts of:

concurrent with the media presentation, retrieving a next file; and

using content of the next file to continue the media presentation.

PTAB

Google filed a petition for IPR with two grounds of unpatentability. First, claims of the ‘806 patent are anticipated by SMIL 1.0 (Synchronized Multimedia Integration Language Specification 1.0). Second, claims of the ‘806 patent would have been obvious in view of SMIL 1.0 in view of the general knowledge of the skilled artisan regarding distributed multimedia presentation systems as of the priority date. Google cited Hua (2PSM: An Efficient Framework for Searching Video Information in a Limited-Bandwidth Environment, 7 Multimedia Systems 396 (1999)) and an expert declaration to argue that pipelining was a well-known design technique, and that a skilled artisan would have been motivated to use pipelining with SMIL.

The PTAB instituted review on three grounds (including two grounds raised by Google and additional ground). In other words, the PTAB exercised its discretion and instituted an IPR on the additional ground that claims would have been obvious over SMIL 1.0 and Hua based on the arguments and evidence presented in the petition.

In the final decision, the PTAB concluded that while Google had not demonstrated that claims were anticipated, Google had demonstrated that claims would have been obvious in view of SMIL 1.0 and that they would have been obvious in view of SMIL 1.0 in view of Hua as well.

CAFC

First, the CAFC held that the PTAB erred by instituting IPR reviews based on a combination of prior art references not presented in Google’s petition. Citing 35 U.S.C. § 314(b) (“[t]he Director shall determine whether to institute an inter partes review . . . pursuant to a petition”), the CAFC held that it is the petition, not the Board’s discretion, that defines the metes and bounds of an IPR.

Second, the CAFC held that while the prior references that can be considered in IPR are limited patents and printed publications only, it does not mean that the skilled artisan’s knowledge should be ignored in the obviousness inquiry. Distinguishing this case from Arendi (where the CAFC held that the PTAB erred in relying on common sense because such reliance was based merely upon conclusory statements and unspecific expert testimony), the CAFC held that the PTAB correctly relied on expert evidence corroborated by Hua in concluding that pipelining is within the general knowledge of a skilled artisan.

Third, with regard to Philips’ arguments that the PTAB’s combination fails because the basis for the combination rests on the patentee’s own disclosure, the CAFC held that the PTAB’s reliance on the specification was proper and that it is appropriate to rely on admissions in the specification for the obviousness inquiry. The CAFC held that the PTAB supported its findings with citations to an expert declaration and the Hua reference. Therefore, the CAFC found that the PTAB’s factual findings underlying its obviousness determination are supported by substantial evidence.

Accordingly, the CAFC affirmed the PTAB’s final decision that claims of the ‘806 patent are unpatentable as obvious.

Takeaway:

- In the obviousness analysis, the general knowledge of a skilled artisan could be used to supply a missing claim limitation from the prior art with expert evidence.

- Patentee’s own disclosure and admission in the specification could be used in the obviousness inquiry. Patent drafters should be careful about what to write in the specification including background session.

- Patent owners should check whether the PTAB instituted IPR on the grounds not advanced in the IPR petition because the PTAB does not discretion to institute IPR based on grounds not advanced in the petition.

Tags: anticipation > General Knowledge > inter partes review > obviousness > Petition > Skilled Artisan

A Claimed Range May be Anticipated and/or Obviousness When the Lower Limit of the Range of the Reference Abuts the Upper limit of the Disputed Claim Range

| January 31, 2020

Genentech, Inc., v. Hospira, Inc.

Prost, Newman and Chen. Opinion by Chen; Dissenting opinion by Newman.

Summary

At an inter partes review (IPR) proceeding, the Board held that a reference that discloses a range where the lower limit of said range abuts the upper limit of the disputed claim range was sufficient to render the disputed patent invalid for anticipation and obviousness. The Majority Opinion of the CAFC affirmed the holding of anticipation and obviousness. The Dissenting Opinion held that there was insufficient evidence to establish anticipation, the wrong reasoning was used to establish obviousness and the findings of Board and the Majority Opinion were based on hindsight.

Details

Background

Protein A affinity chromatography is a purification method, wherein “a composition comprising a mixture of the target antibody and undesired impurities often present in harvested cell culture fluid (HCCF) is placed into the chromatography column…. The target antibody binds to protein A, which is covalently bound to the chromatography column resin, while the impurities and rest of the composition pass through the column…. Next, the antibody of interest is removed from the chromatography column….” Id. at 3. A known problem of protein A affinity chromatography is leaching, wherein protein A detaches from the column and contaminates the purified antibody solution. Thus, further purification steps of the antibody solution retrieved from the column are necessary. Patent 7,807,799 (hereinafter “‘799”), owned by Genentech, addresses the known problem of protein A leaching, with regards to antibodies and other proteins that comprises a CH2/CH3 region. By reducing the temperature of the composition that is subjected to chromatography, leaching can be prevented and/or minimized to an acceptable level of impurity for commercial purposes. Claim 1, herein presented below, is the representative claim.

A method of purifying a protein which comprises CH2/CH3 region, comprising subjecting a composition comprising said protein to protein A affinity chromatography at a temperature in the range from about 10°C to about 18°C.

See Patent ‘799, Col. 35, Lines 44-47.

IPR

Hospira sought an inter partes review (IPR) of claims 1-3 and 5-11 of Patent ‘799. The Board instituted a trial of unpatentability and held that WO95/22389 (hereinafter “WO ‘389) anticipated and WO ‘389, both solely and in combination with secondary references, rendered obvious all of the challenged claims.

WO ‘389 discloses a method for purifying similar antibodies by a protein A affinity chromatography step and then a washing step, comprising washing with at least three column volumes of buffer. WO ‘389 discloses that “[a]ll steps are carried out at room temperature (18-25oC).” Id. at 6.

The Board held that WO ‘389 overlaps the claimed range of “about 10oC to about 18oC”, regardless of the claim construction of “about 18oC”. Further, the Board held that Genentech failed to establish the criticality of the claimed range to the operability of the claimed invention and thus did not overcome the prima facie case of anticipation. Also, the Board held that the claimed temperature range was in reference to the temperature of the composition both prior to and/or during chromatography. The Board held that the disclosed temperature range (18-25oC) of WO ‘389 applied to all components of the purification process and that the temperature of the HCCF composition both prior to and during chromatography were within said range.

Genentech appealed the Board’s holding of unpatentable due to anticipation and obviousness over WO ‘389. Of note, in the Appeal, Genentech did not challenge the Board’s holding that criticality of the claimed temperature range was not established.

CAFC

Anticipation

Genentech argued that the meaning of “all steps are carried out at room temperature (18-25oC)” is applicable only to the temperature of the laboratory and is not applicable to the temperature of the HCCF composition. Genentech asserted that 1) WO ‘389 discloses “steps” where the HCCF composition was cold or frozen, 2) Genentech’s expert and Hospira’s expert testified that typically HCCF coming from a bioreactor, are at a temperature of 37oC, 3) both experts testified WO ‘389 is silent regarding how long HCCF was held prior to chromatography and 4) Genentech’s expert testified that a skilled artisan in industrial processing would perform chromatography of the HCCF as soon as possible, i.e. without waiting for the HCCF to cool to room temperature, unless there were explicit instructions to do so. Id. at 8. Hospira argued that the explicit disclosure of “room temperature (18-25oC)” is with regards to the temperature of performing chromatography and all the components of said purification process, including the HCCF composition. Hospira noted that WO ‘389 disclosed specific temperatures for when the composition was not at room temperature. Further, Hospira’s expert testified that a skilled artisan would perform experiments at “ambient temperature with all materials equilibrated in order to obtain robust scientific data.” Id. at 9. The CAFC affirmed the Board and held that there was substantial evidence that the HCCF composition was within the claimed temperature of “about 10oC to about 18oC.” The CAFC agreed with the Board’s findings that 1) the statement “[a]ll steps are carried out at room temperature (18-25oC)” was a blanket statement and thus, specifying the temperature of HCCF during chromatography is redundant, 2) it disagreed with Genentech’s expert because said opinion was based upon large-scale industrially standards, and 3) it agreed with Hospira’s expert that a skilled artisan would not use HCCF at 37oC in a chromatography column and then report that all steps were performed at room temperature because the warm HCCF would raise the temperature of the entire system. Id. at 10. Lastly, the CAFC disagreed with Genentech’s argument that there was no anticipation because there was a missing limitation in WO ‘389 and agreed with the Board’s finding that WO ‘389 discloses a composition that is at the claimed temperature of “about 10oC to about 18oC” either prior to or during chromatography. (Nidec Motor Corp. v. Zhongshan Board Ocean Motor Co., cited by Genentech, holds that a reference missing a limitation cannot anticipate even if a skilled artisan would ‘at once envisage’ the missing limitation. 851 F.3d 1270, 1274–75 (Fed. Cir. 2017).” Id. at 10.)

Obviousness

The Board, citing the secondary references, determined that the temperature at which chromatography is performed is a result-effective variable and that when temperature is lowered, leaching is reduced. Thus, a skilled artisan would have been motivated to optimize temperature. Genentech argued that there was no reason or motivation to optimize the temperature because “the desire to reduce protein A leaching applies only to the large-scale, industrial purification of therapeutic antibodies for clinical applications…[and] that chilling HCCF for largescale, industrial processes would have been inconvenient, costly, and impractical.” Id. at 13. Hospira argued that a skilled artisan in non‑clinical applications would have been motivated to reduce leaching because leaching damages chromatography columns. The CAFC held that the Board was correct in holding that neither the ‘799 patent nor WO ‘389 are limited to large-scale industrial applications. The CAFC affirmed the Boards’ finding that temperature is a “result-effective variable” and that it would have been routine experimentation for a skilled artisan to optimize the temperature to reduce protein A leaching.

Dissent

Newman dissented and asserted that affirming the holding of invalidity for anticipation and obviousness was an error because none of the prior art shows or suggest the claimed method. Id. at 9. According to Newman, the determination by the Board and the CAFC is based on hindsight. Newman noted that the “retrospective simplicity of the solution apparently led the Board to find it obvious to them, despite the undisputed testimony that no reference suggests this solution to the contamination problem here encountered, as the experts for both sides acknowledged.” Id. at 3. Newman noted that the ‘799 patent disclosed in detail the complexities with regards to obtaining and purifying antibodies, the many factors to consider when performing chromatography, the problems associated with the leaching of protein A, and explained their discovery of the cause of said leaching and their solution to said problem. At the Board, Genentech argued the advantages of their claimed method, i.e. prevent leaching of protein A in protein A affinity chromatography, in contrast to the need to perform additional purification chromatography to remove protein A, as in WO ‘389. Both experts agreed that the reference to room temperature (18-25oC) was in reference to the ambient temperature and was not in reference to the chilled material in the column. “Nonetheless, the PTAB and now my colleagues hold that this ‘room temperature’ range anticipates the ‘799 patent’s chilled range of 10oC-18oC, ignoring the significantly different results in the recited ranges.” Id. at 6.

According to Newman, mere abutment of the 18oC is not anticipation. “Anticipation requires that the same invention, including all claim limitations, was previously described. Nidec Motor Corp. v. Zhongshan Broad Ocean Motor Co., 851 F.3d 1270, 1274– 75 (Fed. Cir. 2017). The “anticipating reference must describe the entirety of the claimed subject matter.” Id. at 7. Newman holds that the affirmation of anticipation fails to consider the “absence of identify of these ranges” (18-25oC vs. about 10oC-about 18oC), fails to consider “the different results at the lower range” and fails to consider “the significance of the purity of the eluted antibody.” Id. at 8 Regarding obviousness, Newman holds that there is no evidence that it was known or suggested that cooling the HCCF composition either prior to or during chromatography would minimize or prevent leaching of the protein A in the purified antibody solution. According to Newman, “the question is not whether it would have been easy to cool the material to the 10ºC–18ºC range; the question is whether it would have been obvious to do so. Contrary to the Board’s and the court’s view, this is not a matter of optimizing a known procedure to obtain a known result; for it was not known that cooling the material for chromatography would avoid contamination of the purified antibody with leached protein A.” Id. at 9. That is, even if it is possible to modify the temperature, Newman asserts that there is no reason or motivation to optimize the temperature to prevent leaching of protein A.

Takeaway

- If possible, establish the criticality of a claimed range. One is encouraged to rebut a prima facie case of anticipation or obviousness by establishing that the claimed range is critical to the operability of the claimed invention.

- If there is an overlap of a disputed claim range and the range disclosed in the prior art, but the results are different, this may be evidence of the criticality of the range.

Post-filing examples, even if made by different method than prior art, may be relied upon to show inherency, particularly if patent owner fails to show that inherent feature is absent in prior art

| January 21, 2020

Hospira, Inc. v. Fresenius Kabi USA, LLC

January 9, 2020

Lourie, Dyk, Moore. Opinion by Lourie.

Summary

The CAFC upheld the obviousness of claims based on an inherency theory. In particular, the CAFC saw no fault in the conclusion that the combination of prior art possessed an inherent property even though the data demonstrating the inherent property was from post-filing examples made by a different method than the combination of cited art. This is because the patent owner failed to demonstrate any situation where the inherent property was not present.

Details

Background

Hospira is the owner of U.S. Patent No. 8,648,106. Fresenius filed an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) stipulating to infringement of claim 6 of the ‘106 patent, but arguing that this claim is invalid. Claim 6 (which depends on claim 1) recites as follows:

6. [A ready to use liquid pharmaceutical composition for parenteral administration to a subject, comprising dexmedetomidine or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof disposed within a sealed glass container, wherein the liquid pharmaceutical composition when stored in the glass container for at least five months exhibits no more than about 2% decrease in the concentration of dexmedetomidine,]

[] wherein the dexmedetomidine or pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof is at a concentration of about 4 μg/mL.

Dexmedetomidine is a sedative that was originally patented in the 1980’s. In 1989, safety studies were performed using a 20 µg/mL dosage in humans, but were eventually abandoned due to adverse side effects.

In 1994, FDA approval was granted to market a 100 µg/mL dose of dexmedetomidine under the name “Precedex Concentrate.” Precedex Concentrate was provided in 2 mL sealed glass vials/ampoules with coated rubber stoppers. Precedex Concentrate was sold with instructions for diluting to a concentration of 4 µg/mL prior to use.

Additionally, in 2002, a 500 µg/mL “ready to use” formulation of dexmedetomidine was granted approval for veterinary use in Europe. This product was called Dexdomitor, and was stored in 10 mL glass vials sealed with a coated rubber stopper. Dexdomitor has a 2 year shelf life.

The ‘106 patent explained that the prior art dexmedetomidine was problematic due to the requirement for dilution, and disclosed a premixed, “ready to use” formulation, which can be administered without dilution. The ‘106 patent stated that the invention was based in part on the discovery that the premixed dexmedetomidine “remains stable and active after prolonged storage.” The specification included studies of dexmedetomidine potency over time under different storage conditions, such as the material of the container. Further, the specification disclosed a manufacturing method that provided nitrogen gas into the headspace of the bottle.

District Court

The district court concluded that claim 6 was obvious in view of (a) the combination of Precedex Concentrate (100 µg/mL requiring dilution) and the knowledge of a person skilled in the art, and (b) the combination of Precedex Concentrate (100 µg/mL requiring dilution) and Dexdomitor (500 µg/mL not requiring dilution). In particular, the district court focused on the “4 µg/mL preferred embodiment”: a glass container made of glass and a rubber-coated stopper with ready to use 4 µg/mL dexmedetomidine. The main issue related to the “about 2%” limitation.

The district

court concluded that the “about 2%” limitation was inherent in the prior art’s

“4 µg/mL preferred embodiment.” To reach this conclusion, the district court

relied on evidence of 20+ tested samples, all of which met the “about 2%”

limitation. The court also relied on

expert testimony that the concentration of dexmedetomidine does not impact its

stability. Further, the court relied on the fact that neither the label of

Precedex Concentrate nor the label of Dexdomitor mentions chemical

stabilizers. Importantly, the district

court found insufficient evidence that it would have been expected that a lower

concentration of dexmedetomidine would reduce stability, or that oxidation

would occur in the absence of a nitrogen gas environment. The district court concluded that dexmedetomidine

is a “rock stable molecule” and that claim 6 is therefore invalid as obvious in

view of the prior art.

CAFC

At the CAFC, the main issue raised was whether the inherency conclusion of the district court was improper because it relied on non-prior art embodiments, rather than the alleged obvious combination of prior art. In particular, the data relied upon by the district court was entirely from Hospira’s NDA for Precedex Premix and Fresenius’s ANDA product. Both of these are after the filing date of the application. Both were made using the nitrogen gas environment method as described in the specification. As such, Hospira argued that it cannot be said that the data demonstrate the inherency of a preferred embodiment which may or may not be made using this manufacturing process.

However, the CAFC agreed with Fresenius that it was not an error to point to post-filing data in support of an inherency conclusion. Although the later evidence is not prior art, it can nonetheless be used to demonstrate the properties of the prior art. The NDA and ANDA data merely served as evidence to show whether there was the decrease in concentration over time of the 4 µg/mL preferred embodiment.

Additionally, the CAFC noted that claim 6 is not a method claim or a product-by-process claim. Since claim 6 includes no limitations relating to a nitrogen gas environment in the glass container, such limitations should not be read into the claim. Thus, the district court properly ignored the process by which the samples were prepared when considering inherency.

The CAFC then highlighted that the record included evidence that concentration does not affect the stability of dexmedetomidine, and also criticized Hospira for failing to present any examples of the 4 µg/mL preferred embodiment which did not satisfy the “about 2%” limitation. Furthermore, Hospira failed to demonstrate that the reason why the 20+ examples satisfied the “about 2%” limitation was because of the nitrogen gas in the glass container, and likewise that samples made by a different method would fail to satisfy the “about 2%” limitation.

Additionally, Hospira argued that the district court applied the wrong standard to inherency by applying a “reasonable expectation of success” standard. Although the CAFC agreed that the district court conflated two issues, they found that the district court’s “unnecessary analysis” was a harmless error and does not impact the outcome of the case. In other words, if a property is inherently present, there is no further question of whether one has a reason expectation of success in obtaining this property.

Returning to the merits, the CAFC concluded that claim 6 is obvious. Since there are no other relevant limitations recited in claim 6, the mere recitation of the inherent “about 2% limitation” cannot render the claim nonobvious. Rather, the patent was merely based on a discovery that dexmedetomidine is stable after long-term storage, but does not require any additional manufacturing limitations or the like.

Takeaway

-Applicants and patent owners should be aware that post-filing data can demonstrate inherency of prior art in some situations.

-When facing an issue of inherency, the Applicant or patent owner should focus on providing evidence to demonstrate the lack of an allegedly inherent feature in some situations, rather than criticizing the experimental design of the data alleged to show inherency.

-Applicants and patent owners should take care that non-inherency arguments are commensurate in scope with the claims. Here, the patent owner should have presented evidence relating to differences between drug potency in a nitrogen gas environment (as in the data relied upon by the court) as compared to a normal air environment (as in the combination of prior art). Although the claims do not require any particular environment, such data could have shown that even if the nitrogen gas environment (not prior art) satisfied the “about 2% limitation,” the non-nitrogen gas environment (prior art) did not necessarily satisfy the “about 2% limitation.”

-Applicants should be sure to claim all disclosed important features. In this case, positively reciting the nitrogen gas environment and the container at a minimum level of detail may have been sufficient to save the claims from obviousness.

Presenting multiple arguments in prosecution risks prosecution history estoppel on each of them

| November 8, 2019

Amgen Inc. v. Coherus BioSciences Inc.

July 29, 2019

Before Reyna, Hughes, and Stoll. Opinion by Stoll.

Summary

The CAFC affirmed a district court decision holding that Amgen had failed to state a claim and dismissed Amgen’s suit against Coherus for patent infringement under the doctrine of equivalents, in view of Amgen’s clear and unmistakable disclaimer of claim scope during prosecution.

Details

Amgen Inc. and Amgen Manufacturing Ltd. (“Amgen”) sued Coherus BioSciences Inc. for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 8,273,707 (the ‘707 patent). The patent relates to methods of purifying proteins using hydrophobic interaction chromatography (“HIC”), in which a buffered salt solution containing the desired protein is poured into a HIC column and the proteins are bound to a column matrix while the impurities are washed out. However, only a limited amount of protein can bind to the matrix. If too much protein is loaded on the column, some of the protein will be lost to the solution phase before elution.

Conventionally, a higher salt concentration in a buffer solution is provided to increase the dynamic capacity of the HIC column, but the higher salt concentration causes protein instability. Amgen’s ‘707 patent discloses a process that increases the dynamic capacity of a HIC column by providing combinations of salts instead of using a single salt.

According to the ‘707 patent, any one of the three combinations of salts – citrate and sulfate, citrate and acetate, or sulfate and acetate – allows for a decreased concentration of at least one of the salts to achieve a greater dynamic capacity without compromising the quality of the protein separation.

During prosecution, the Examiner rejected the claims as being obvious in view of U.S. Patent No. 5,231,178 (“Holtz”). In reply to the Examiner’s rejection, Amgen argued that:

(1) The pending claims recite a particular combination of salts. No combinations of salts are taught nor suggested in Holtz;

(2) No particular combinations of salts recited in the pending claims are taught or suggested in Holtz; and

(3) Holtz does not teach dynamic capacity at all.

Amgen also attached a declaration from the inventor. The declaration stated that the use of the three salt combinations leads to substantial increases in the dynamic capacity of a HIC column and “[use] of this particular combination of salts greatly improves the cost-effectiveness of commercial manufacturing by reducing the number of cycles required for each harvest and reducing the processing time for each harvest.”

The Examiner again rejected Amgen’s argument and took the position that the prior art does disclose salts used in a method of purification and that adjustment of conditions was within the skill of an ordinary artisan. This time, in response to the Examiner’s position, Amgen replied that Holtz does not disclose any combination of salts and does not mention the dynamic capacity of a HIC column. In particular, Amgen stated that it was a “lengthy development path” when choosing a working salt combination and that merely adding a second salt would not have been expected to result in the invention. The Examiner allowed the claims.

In 2016, Coherus sought FDA approval to market a biosimilar version of Amgen’s pegfilgrastim product. In 2017, Amgen sued Coherus for infringing the ‘707 patent under the doctrine of equivalents because Coherus’s process did not match any of the three explicitly recited salt combinations in the ‘707 patent. Coherus moved to dismiss Amgen’s complaint for failure to state a claim.

The district court agreed to dismiss the complaint. The district court noted that during prosecution, Amgen had distinguished Holtz by repeatedly arguing that Holtz did not disclose “one of the particular, recited combinations of salts” in the two responses and in the declaration. The district court held that “[t]he prosecution history, namely, the patentee’s correspondence in response to two office actions and a final rejection, shows a clear and unmistakable surrender of claim scope by the patentee.” In addition, the district court held that “by disclosing but not claiming the salt combination used by Coherus, Amgen had dedicated that particular combination to the public.”

Amgen appealed.

The CAFC affirmed the district Court’s dismissal and found that the “prosecution history estoppel has barred Amgen from succeeding on its infringement claim under the doctrine of equivalents.”

In the appeal, Amgen argued that it only had distinguished Holtz by stating that Holtz does not disclose increasing any dynamic capacity or mention any salt combination. Amgen also argued that the prosecution history should not apply here because the last response filed prior to allowance did not make the argument that Holtz failed to disclose the particular salt combinations.

Regarding Amgen’s first point – that during prosecution, only dynamic capacity had been used to distinguish Holtz – the CAFC noted the three grounds on which Amgen has relied for distinguishing Holtz, and the fact that Amgen had quoted the declaration in support of the particular combination of salts recited in the claims. The CAFC explained that “separate arguments create separate estoppels as long as the prior art was not distinguished based on the combination of these various grounds.”

The CAFC also disagreed with Amgen’s second point (that prosecution history estoppel should not apply because of their last response), commenting that “there is no requirement that argument-based estoppel apply only to arguments made in the most recent submission before allowance… We see nothing in Amgen’s final submission that disavows the clear and unmistakable surrender of unclaimed salt combinations made in Amgen’s response.”

The CAFC held that the prosecution history estoppel applied and affirmed the District Court’s order dismissing Amgen’s complaint for failure to state a claim. The CAFC did not discuss whether Amgen dedicated unclaimed salt combinations to the public.

Takeaway

- Prosecution history estoppel can be triggered, not only by narrowing amendments, but also by arguments, even without any amendments.

- Presenting multiple arguments does not eliminate the risk of triggering estoppel for each of them.

- When writing an argument, avoid using expressions that are not recited in the claims (when discussing the claimed invention) or the cited documents (when discussing the state of the art).

A Good Fry: Patent on Oil Quality Sensing Technology for Deep Fryers Survives Inter Partes Review

| October 4, 2019

Henny Penny Corporation v. Frymaster LLC

September 12, 2019

Before Lourie, Chen, and Stoll (Opinion by Lourie)

Summary

In an appeal from an inter partes review, the Federal Circuit affirmed the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s decision to uphold the validity of a patent relating to oil quality sensing technology for deep fryers. The Board found, and the Federal Circuit agreed, that the disadvantages of pursuing the challenger’s proposed modification of the prior art weighed against obviousness, in the absence of some articulated rationale as to why a person of ordinary skill in the art would have pursued that modification. In addition, the Federal Circuit reiterated that as a matter of procedure, the scope of an inter partes review is limited to the theories of unpatentability presented in the original petition.

Details

Fries are among the most common deep-fried foods, and McDonald’s fries may still be the most popular and highest-consumed worldwide. But, there would be no McDonald’s fries without a deep fryer and a good pot of oil, and Frymaster LLC (“Frymaster”) is the maker of some of McDonald’s deep fryers.

During deep frying, chemical and thermal interactions between the hot frying oil and the submerged food cause the food to cook. These interactions degrade the quality of the oil. In particular, chemical reactions during frying generate new compounds, including total polar materials (TPM), that can change the oil’s physical properties and electrical conductivity.

Frymaster’s fryers are equipped with integrated oil quality sensors (OQS), which monitor oil quality by measuring the oil’s electrical conductivity as an indicator of the TPM levels in the oil. This sensor technology is embodied in Frymaster’s U.S. Patent No. 8,497,691 (“691 patent”).

The 691 patent describes an oil quality sensor that is integrated directly into the circulation of cooking oil in a deep fryer, and is capable of taking measurements at the deep fryer’s operational temperatures of 150-180°C, i.e., without cooling the hot oil.

Claim 1 of the 691 patent is representative:

1. A system for measuring the state of degradation of cooking oils or fats in a deep fryer comprising:

at least one fryer pot;

a conduit fluidly connected to said at least one fryer pot for transporting cooking oil from said at least one fryer pot and returning the cooking oil back to said at least one fryer pot;

a means for re-circulating said cooking oil to and from said fryer pot; and

a sensor external to said at least on[e] fryer pot and disposed in fluid communication with said conduit to measure an electrical property that is indicative of total polar materials of said cooking oil as the cooking oil flows past said sensor and is returned to said at least one fryer pot;

wherein said conduit comprises a drain pipe that transports oil from said at least one fryer pot and a return pipe that returns oil to said at least one fryer pot,

wherein said return pipe or said drain pipe comprises two portions and said sensor is disposed in an adapter installed between said two portions, and

wherein said adapter has two opposite ends wherein one of said two ends is connected to one of said two portions and the other of said two ends is connected to the other of said two portions.

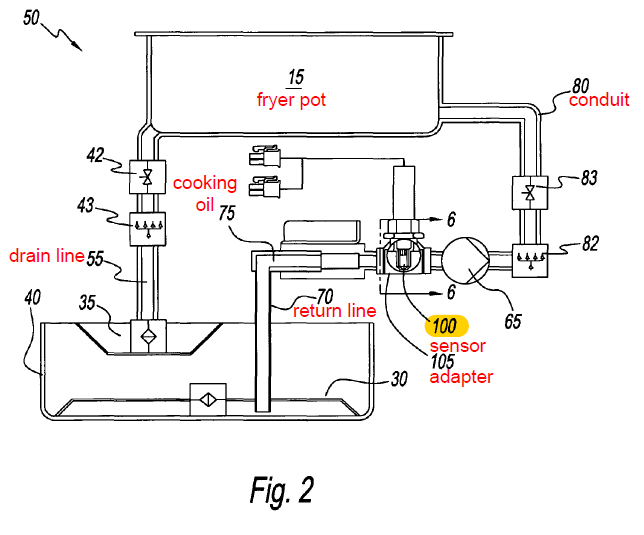

Figure 2 of the 691 patent illustrates the structure of Frymaster’s system:

Henny Penny Corporation (HPC) is a competitor of Frymaster, and initiated an inter partes review of the 691 patent.

In its petition, HPC challenged claim 1 of the 691 patent as being obvious over Kauffman (U.S. Patent No. 5,071,527) in view of Iwaguchi (JP2005-55198).

Kauffman taught a system for “complete analysis of used oils, lubricants, and fluids”. The system included an integrated electrode positioned between drain and return lines connected to a fluid reservoir. The electrode measured conductivity and current to monitor antioxidant depletion, oxidation initiator buildup, product buildup, and/or liquid contamination. Kauffman’s system operated at 20-400°C. However, Kauffman did not teach monitoring TPMs.

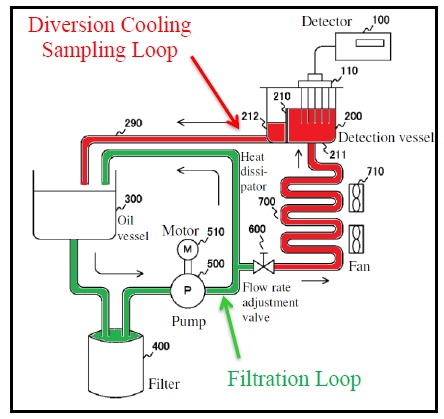

Iwaguchi taught monitoring TPMs to gauge quality of oil in deep fryers. However, Iwaguchi cooled the oil to 40-80°C before taking measurements. If the oil temperature was outside the disclosed range, Iwaguchi’s system would register an error. Specifically, oil was diverted from the frying pot to a heat dissipator where the oil was cooled to the appropriate temperature, and then to a detection vessel where a TPM detector measured the electrical properties of the oil to detect TPMs. Iwaguchi taught that cooling relieved heat stress on the detector, prevented degradation, and obviated the need for large conversion tables.

The parties’ dispute focused on the sensor feature of the 691 patent.

In the initial petition, HPC argued simply that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have found it obvious to modify Kauffman’s system to “include the processor and/or sensor as taught by Iwaguchi.”

In its patent owner’s response, Frymaster disputed HPC’s proposed modification. Frymaster argued that Iwaguchi’s “temperature sensitive” detector would be inoperable in an “integrated” system such as that taught in Kauffman, unless Kauffman’s system was further modified to add an oil diversion and cooling loop. However, such an addition would have been complex, inefficient, and undesirable to those skilled in the art.

In its reply, HPC changed course and argued that it was unnecessary to swap the electrode in Kauffman’s system for Iwaguchi’s detector. HPC argued that Kauffman’s electrode was capable of monitoring TPMs by measuring conductivity, and that Iwaguchi was relevant only for teaching the general desirability of using TPMs to assess oil quality.

However, whereas HPC’s theory of obviousness in its original petition was based on a modification of the physical structure of Kauffman’s system, HPC’s reply proposed changing only the oil quality parameter being measured. During the oral hearing before the Board, HPC’s counsel even admitted to this shift in HPC’s theory of obviousness.

In its final written decision, the Board determined, as a threshold matter of procedure, that HPC impermissibly presented a new theory of obviousness in its reply, and that the patentability of the 691 patent would be assessed only against the grounds asserted in HPC’s original petition.

The Board’s final written decision thus addressed only whether the person skilled in the art would have been motivated to “include”—that is, integrate—Iwaguchi’s detector into Kauffman’s system. The Board found no such motivation.

The Board’s reasoning largely mirrored Frymaster’s arguments. Kauffman’s system did not include a cooling mechanism that would have allowed Iwaguchi’s temperature-sensitive detector to work. Integrating Iwaguchi’s detector into Kauffman’s system would therefore necessitate the addition of the cooling mechanism. The Board agreed that the disadvantages of such additional construction outweighed the “uncertain benefits” of TPM measurements over the other indicia of oil quality already being monitored in Kauffman.

On appeal, HPC raised two issues: first, the Board construed the scope of HPC’s original petition overly narrowly; and second, the Board erred in its conclusion of nonobviousness.[1]

The Federal Circuit sided with the Board on both issues.

On the first issue, the Federal Circuit did a straightforward comparison of HPC’s petition and reply. In the petition, HPC proposed a physical substitution of Iwaguchi’s detector for Kauffman’s electrode. In the reply, HPC proposed using conductivity measured by Kauffman’s electrode as a basis for calculating TPMs. The apparent differences between the two theories of obviousness, together with the “telling” confirmation of HPC’s counsel during oral hearing that the original petition espoused a physical modification, made it easy for the Federal Circuit to agree with the Board’s decision to disregard HPC’s alternative theory raised in its reply.

The Federal Circuit reiterated the importance of a complete petition:

It is of the utmost importance that petitioners in the IPR proceedings adhere to the requirement that the initial petition identify ‘with particularity’ the ‘evidence that supports the grounds for the challenge to each claim.

On the second issue of obviousness, HPC argued that the Board placed undue weight on the disadvantages of incorporating Iwaguchi’s TPM detector into Kauffman’s system.

Here, the Federal Circuit reiterated “the longstanding principle that the prior art must be considered for all its teachings, not selectively.” While “[t]he fact that the motivating benefit comes at the expense of another benefit…should not nullify its use as a basis to modify the disclosure of one reference with the teachings of another”, “the benefits, both lost and gained, should be weighed against one another.”

The Federal Circuit adopted the Board’s findings on the undesirability of HPC’s proposed modification of Kauffman, agreeing that the “tradeoffs [would] yield an unappetizing combination, especially because Kauffman already teaches a sensor that measures other indicia of oil quality.”

At first glance, the nonobviousness analysis in this decision seems to involve weighing the disadvantages and advantages of the proposed modification. However, looking at the history of this case, I think the problem with HPC’s arguments was more fundamentally that they never identified a satisfactory motivation to make the proposed modification. HPC’s original petition argued that the motivation for integrating Iwaguchi’s detector into Kauffman’s system was to “accurately” determine oil quality. This “accuracy” argument failed because it was questionable whether Iwaguchi’s detector would even work at the operating temperature of a deep fryer. Further, HPC did not argue that the proposed modification was a simple substitution of one known sensor for another with the predictable result of measuring TPMs. And when Kauffman argued that the substitution was far from simple, HPC failed to counter with adequate reasons why the person skilled in the art would have pursued the complex modification.

Takeaway

- The petition for a post grant review defines the scope of the proceeding. Avoid being overly generic in a petition for post grant review. It may not be possible to fill in the details later.

- Context matters. If an Examiner is selectively citing to isolated disclosures in a prior art out of context, consider whether the context of the prior art would lead away from the claimed invention.

- The MPEP is clear that the disadvantages of a proposed combination of the prior art do not necessarily negate the motivation to combine (see, e.g., MPEP 2143(V)). The disadvantages should preferably nullify the Examiner’s reasons for the modification.

[1] On the issue of obviousness, HPC also objected to the Board’s analysis of Frymaster’s proffered evidence of industry praise as secondary considerations. This objection is not addressed here.

A Change in Language from IPR Petition to Written Decision May Not Result in A Change in Theory of Motivation to Combine

| September 25, 2019

Arthrex, Inc. v. Smith & Nephew, Corp.

August 21, 2019

Dyk, Chen, Opinion written by Stoll

Summary

The CAFC affirmed the Board’s decision that claims 10 and 11 of Patent ‘541 were obvious over Gordon in view of West and that the IPR proceeding was constitutional. The CAFC held that minor variations in wording, from the IPR Petition to the written Final Decision, do not violate the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). Further, the CAFC rejected Arthrex’s argument to reconsider evidence that was contrary to the Board’s decision since there was sufficient evidence to support the Board’s findings of obviousness by the preponderance of evidence standard.

Details

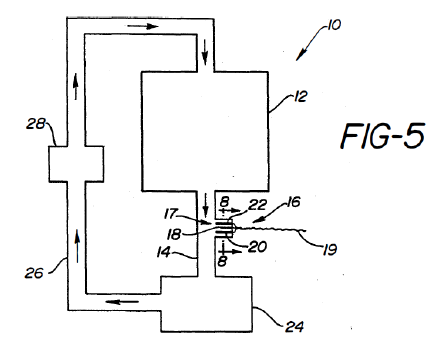

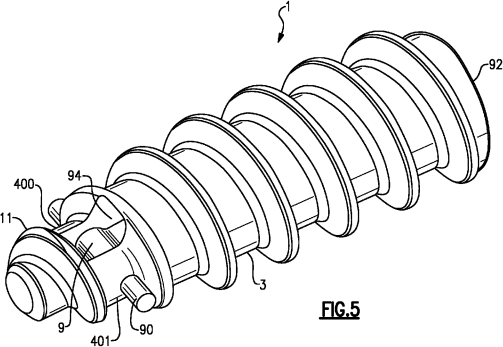

Arthrex’s Patent No. 8,821,541 (hereinafter “Patent ’541”) is directed towards a surgical suture anchor that reattaches soft tissue to bone. A feature of the suture anchor of Patent ‘541 is that the “fully threaded suture anchor’ includes ‘an eyelet shield that is molded into the distal part of the biodegradable suture anchor’”, wherein the eyelet shield is an integrated rigid support that strengthen the suture to the soft tissue. Id. at 2 and 3. The specification discloses that “because the support is molded into the anchor structure (as opposed to being a separate component), it ‘provides greater security to prevent pull-out of the suture.’ Id at col 5 ll. 52-56.” Id. at 3. Figure 5 of Patent ‘541 illustrates an embodiment of the suture anchor (component 1), wherein component 9 is the eyelet shield (integral rigid support) and component 3 is the body wherein helical threading is formed.

Claims 10 and 11 of Patent ‘541 are herein enclosed (emphasis added to the claim terms at issue in the dispute)

10. A suture anchor assembly comprising:

an anchor body including a longitudinal axis, a proximal end, a distal end, and a central passage extending along the longitudinal axis from an opening at the proximal end of the anchor body through a portion of a length of the anchor body, wherein the opening is a first suture opening, the anchor body including a second suture opening disposed distal of the first suture opening, and a third suture opening disposed distal of the second suture opening, wherein a helical thread defines a perimeter at least around the proximal end of the anchor body;

a rigid support extending across the central passage, the rigid support having a first portion and a second portion spaced from the first portion, the first portion branching from a first wall portion of the anchor body and the second portion branching from a second wall portion of the anchor body, wherein the third suture opening is disposed distal of the rigid support;

at least one suture strand having a suture length threaded into the central passage, supported by the rigid support, and threaded past the proximal end of the anchor body, wherein at least a portion of the at least one suture strand is disposed in the central passage between the rigid support and the opening at the proximal end, and the at least one suture strand is disposed in the first suture opening, the second suture opening, and the third suture opening; and

a driver including a shaft having a shaft length, wherein the shaft engages the anchor body, and the suture length of the at least one suture strand is greater than the shaft length of the shaft.

11. A suture anchor assembly comprising:

an anchor body including a distal end, a proximal end having an opening, a central longitudinal axis, a first wall portion, a second wall portion spaced opposite to the first wall portion, and a suture passage beginning at the proximal end of the anchor body, wherein the suture passage extends about the central longitudinal axis, and the suture passage extends from the opening located at the proximal end of the anchor body and at least partially along a length of the anchor body, wherein the opening is a first suture opening that is encircled by a perimeter of the anchor body, a second suture opening extends through a portion of the anchor body, and a third suture opening extends through the anchor body, wherein the third suture opening is disposed distal of the second suture opening;

a rigid support integral with the anchor body to define a single-piece component, wherein the rigid support extends across the suture passage and has a first portion and a second portion spaced from the first portion, the first portion branching from the first wall portion of the anchor body and the second portion branching from the second wall portion of the anchor body, and the rigid support is spaced axially away from the opening at the proximal end along the central longitudinal axis; and

at least one suture strand threaded into the suture passage, supported by the rigid support, and having ends that extend past the proximal end of the anchor body, and the at least one suture strand is disposed in the first suture opening, the second suture opening, and the third suture opening.

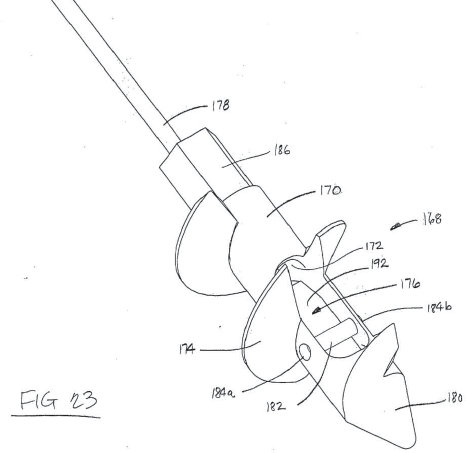

Smith & Nephew (hereinafter “Smith”) initiated an inter partes review of claims 10 and 11 of Patent ‘541. Smith alleged that claims 10 and 11 of Patent ‘541 were invalid as obvious over Gordon (U.S. Patent Application Publication No. 2006/0271060) in view of West (U.S. Patent No. 7,322,978) and alleged that claim 11 was anticipated by Curtis (U.S. Patent No. 5,464,427) (The discussion regarding Curtis (U.S. Patent No. 5,464,427) is not herein included). Smith argued that Gordon disclosed all the features claimed except for the rigid support. Gordon disclosed “a bone anchor in which a suture loops about a pulley 182 positioned within the anchor body. Figure 23 illustrates the pully 182 held in place in holes 184a, b.” Id. at 5 and 6.

Figure 23 of Gordon

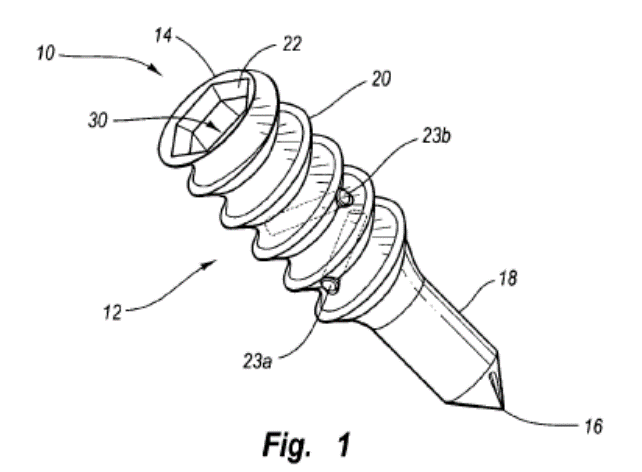

Smith acknowledged that the pulley of Gordon was not “integral with the anchor body to define a single-piece component”, a feature recited in claim 11 of Patent ‘541. Smith cited West to allege obviousness of this feature. West also disclosed a bone anchor wherein one or more pins are fixed within the bore of the anchor body. In West, “to manufacture the bone anchor, ‘anchor body 12 and posts 23 can be cast and formed in a die. Alternatively anchor body 12 can be cast or formed and post 23a and 23b inserted later.’” Id. at 7.

Figure 1 of West

Smith argued that it would have been obvious to a skilled artisan to form the bone anchor of Gordon by the casting process of West to thereby create a rigid support integral with the anchor body to define a single piece component, as recited in claim 11 of Patent ‘541. Smith’s expert testified that the casting process of West would “minimize the materials used in the anchor, thus facilitating regulatory approval, and would reduce the likelihood of the pulley separating from the anchor body.” Id. at 7. Smith asserted that the casting process of West was well-known in the art and that such a manufacturing process “would have been a simple design choice.” Id. at 7. Arthrex argued that a skilled artisan would not have been motivated to modify Gordon in view of West. The Board agreed with Smith that the claims were unpatentable. Arthrex filed an appeal.

Arthrex appealed the Board’s decision that Smith proved unpatentability of claims 10 and 11 in view of Gordon and West, on both a procedurally and a substantively basis, and the constitutionality of the IPR proceeding. The CAFC found that Arthrex’s procedural rights were not violated; that the Decision by the Board was supported by substantial evidence and the application of IPR to Patent ‘541 was constitutional.

IPR proceedings are formal administrative adjudications subject to the procedural requirements of the APA. See, e.g., Dell Inc. v. Acceleron, LLC, 818 F.3d 1293, 1298 (Fed. Cir. 2016); Belden, 805 F.3d at 1080. One of these requirements is that “‘an agency may not change theories in midstream without giving respondents reasonable notice of the change’ and ‘the opportunity to present argument under the new theory.’” Belden, 805 F.3d at 1080 (quoting Rodale Press, Inc. v. FTC, 407 F.2d 1252, 1256–57 (D.C. Cir. 1968)); see also 5 U.S.C. § 554(b)(3). Nor may the Board craft new grounds of unpatentability not advanced by the petitioner. See In re NuVasive, Inc., 841 F.3d 966, 971–72 (Fed. Cir. 2016); In re Magnum Oil Tools Int’l, Ltd., 829 F.3d 1364, 1381 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

Id. at 9.

Arthrex argued that the Board’s decision relied on a new theory of motivation to combine. Arthrex argued that the new theory violated their procedural rights by depriving them an opportunity to respond to said new theory. Arthrex argued that the Board’s reasoning differed from the Smith Petition by describing the casting method of West as “preferred.” The CAFC held that while the language used by the Board did differ from the Petition, said deviation did not introduce a new issue or theory as to the reason for combining Gordon and West. West disclosed “an ‘anchor body 12 and posts 23 can be cast and formed in a die. Alternatively anchor body 12 can be cast or formed and posts 23a and 23b inserted later’.” Id. at 10. The Smith Petition asserted that “a person of ordinary skill would have had ‘several reasons’ to combine West and Gordon, including that the casting process disclosed by West was a ‘well-known technique [whose use] would have been a simple design choice’.” (emphasis added) Id. at 10. In the written decision by the Board, the Board characterized West as disclosing two manufacturing methods, wherein the casting method was the “primary” and “preferred” method, and thus, a skilled artisan would have “applied West’s casting method to Gordon because choosing the ‘preferred option’ presented by West ‘would have been an obvious choice of the designer’.” Id. at 11. The CAFC noted that while the Board’s language of “preferred” differed from the language of the Petition, i.e. “well-known”, “accepted” and “simple”, the Board nonetheless relied upon the same disclosure of West as the Petition, the same proposed combination of the references and ruled on the same theory of obviousness, as presented in the Petition. “[t]he mere fact that the Board did not use the exact language of the petition in the final written decision does not mean it changed theories in a manner inconsistent with the APA and our case law…. the Board had cited the same disclosure as the petition and the parties had disputed the meaning of that disclosure throughout the trial. Id. As a result, the petition provided the patent owner with notice and an opportunity to address the portions of the reference relied on by the Board, and we found no APA violation.” Id. at 11.

Next, Arthrex argued that even if the Board’s decision was procedurally proper, an error was made by finding Smith had established a motivation to combine the cited art by a preponderance of the evidence. The CAFC held that there was sufficient substantial evidence to support the Board’s finding that a skilled artisan would be motivated to use the casting method of West to form the anchor of Gordon. First, the Board noted West’s disclosure of two methods of making a rigid support. Second, the wording by West suggested that casting was the preferred method. Third, Smith’s experts testified that the casting method would likely produce a stronger anchor, which in turn would be more likely to be granted regulatory approval. Also, casting would decrease manufacturing cost, produce an anchor that is less likely to interfere with x-rays and would reduce stress concentrations on the anchor. The CAFC agreed with Arthrex that there was some evidence that contradicts the Board’s decision, such as Arthrex’s expert’s testimony. However, “the presence of evidence supporting the opposite outcome does not preclude substantial evidence from supporting the Board’s fact finding. See, e.g., Falkner v. Inglis, 448 F.3d 1357, 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2006)”. Id. at 14. The CAFC refused to “reweight the evidence.” Id. at 14.

Lastly, the CAFC addressed Arthrex’s argument that an IPR is unconstitutional when applied retroactively to a pre-AIA patent. Since this argument was first presented on appeal, the CAFC could have chosen not to address it. However, exercising its discretion, the CAFC held that an IPR proceeding against Patent ‘541 was constitutional. Patent ‘541 was filed prior to the passage of the AIA, but was issued almost three years after the passage of the AIA and almost two years after the first IPR proceedings, on September 2, 2014. “As the Supreme Court has explained, ‘the legal regime governing a particular patent ‘depend[s] on the law as it stood at the emanation of the patent, together with such changes as have since been made.’” Eldred v. Ashcroft, 537 U.S. 186, 203 (2003) (quoting McClurg v. Kingsland, 42 U.S. 202, 206 (1843)). Accordingly, application of IPR to Arthrex’s patent cannot be characterized as retroactive.” Id. at 18. The CAFC further explained that even if Patent ‘541 issued prior to the AIA, an IPR would have been constitutional. “[t]he difference between IPRs and the district court and Patent Office proceedings that existed prior to the AIA are not so significant as to ‘create a constitutional issue’ when IPR is applied to pre-AIA patents.” Id. at 18.

Takeaway

- Slight changes in language does not create a new theory of motivation to combine.

- However, a new theory of motivation to combine

may exist when:

- the Board

creates a new theory of obviousness by mixing arguments from two different

grounds of obviousness presented in a Petition.

- In re Magnum Oil Tools Int’l, Ltd., 829 F.3d 1364, 1372–73, 1377 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

- the claim construction by the Board varies

significantly from the uncontested construction announced in an institution

decision.

- SAS Institute v. ComplementSoft, LLC, 825 F.3d 1341, 1351 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

- the Board

relies upon a portion of the prior art, as an essential part of its obviousness

finding, that is different from the portions of the prior art cited in the

Petition.

- In re NuVasive, Inc., 841 F.3d 966, 971 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

- the Board

creates a new theory of obviousness by mixing arguments from two different