Joint Inventorship Gone Up In Smoke For Want of Significant Contribution

| June 16, 2023

HIP, INC. v. HORMEL FOODS CORPORATION

Decided: May 2, 2023

Before Lourie, Clevenger, and Taranto. Opinion by Lourie.

Summary

The CAFC held that an alleged inventor did not make a contribution sufficiently significant in quality to establish joint inventorship to an issued patent, where the alleged contributed concept was only minimally mentioned throughout the entirety of the patent document including the specification, drawings and claims.

Details

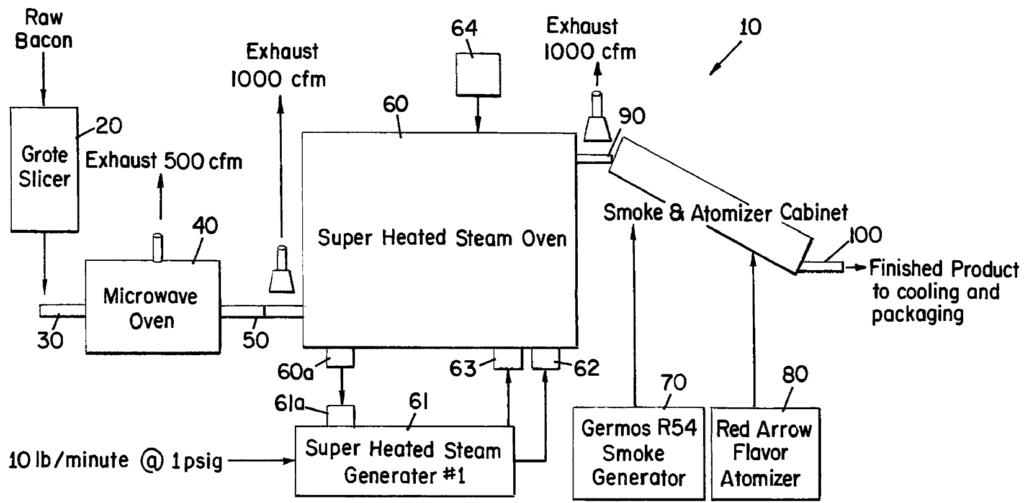

Hormel Foods Corporation (“Hormel”) owns U.S. Patent 9,980,498 (the “’498 patent”) relating to production of precooked bacon. While a traditional bacon producer would “precook” or prepare the bacon prior to sale by a certain type of oven, such as microwave or steam oven, the invention uses a two-step, hybrid oven system to improve the precooking process. FIG. 1, reproduced below, depicts a principle embodiment where a microwave oven 40 initially heats bacon so as to form a coating of melted fat around the meat piece, followed by a super heated steam oven 60 equipped with external steam source 61 for further cooking to a finishing temperature:

Per the ‘498 patent, the first step of forming the “fat barrier” protects the underlying meat from condensation and resulting dilution of flavor, whereas the second step using the external gas source prevents the oven’s internal surfaces from becoming hotter than the smoke point of bacon fat, which would otherwise cause off flavor of the resulting product.

The ’498 patent includes independent claims 1, 5 and 13, defining the inventive method using slightly different languages from each other. As relevant on appeal, claims 1 and 13 both recite a particular mode of cooking in the first step of the hybrid system as “preheating … with a microwave oven,” whereas claim 5 recites three alternative preheating techniques using a Markush language, “selected from the group consisting of a microwave oven, an infrared oven, and hot air.”

As part of its R&D efforts toward the improved precooking process, Hormel contacted Unitherm Food Systems, Inc. (“Unitherm”), now HIP, a manufacturer of cooking machinery such as industrial ovens. The parties jointly agreed to develop an oven to be used in a two-step cooking process. The alleged inventor in question, David Howard of Unitherm, was involved in those meetings and testing process where he allegedly disclosed an infrared heating concept to Hormel. As Hormel’s further R&D—including testing with their own facility instead of Unitherm’s facility—eventually led to the discovery of the inventive two-step process, Hormel filed for a patent. The resulting ’498 patent named four inventors, which did not include Howard.

HIP sued Hormel in the District Court for the District of Delaware, alleging that Howard was either the sole inventor or a joint inventor of the ’498 patent. HIP argued, among other things, that Howard contributed to preheating with an infrared oven, the concept recited in independent claim 5. The district court held that although Howard was not the sole inventor, his contribution of the infrared oven concept made him a joint inventor of the ’498 patent. Hormel appealed.

On appeal, Hormel argued, among other things,[1] that Howard was not a joint inventor because the infrared oven concept was well known, and his alleged contribution was insignificant in quality relative to the extent of the full invention.

Specifically, the joint inventorship issue was argued based on the three-part test set forth in Pannu v. Iolab Corp., 155 F.3d 1344, 1351. Under Pannu, to qualify as an additional joint inventor, one must have:

(1) contributed in some significant manner to the conception of the invention;

(2) made a contribution to the claimed invention that is not insignificant in quality, when that contribution is measured against the dimension of the full invention; and

(3) did more than merely explain to the real inventors well-known concepts and/or the current state of the art.

Hormel asserted that Howard met none of the three factors, and HIP countered that each and every factor was met so as to establish joint inventorship.

The CAFC ultimately sided with Hormel. The CAFC focused its analysis on the second Pannu factor, noting specific circumstances:

- Small # of times mentioned in the specification: The alleged contribution, preheating with an infrared oven, is “mentioned only once in the … specification as an alternative heating method to a microwave oven.”

- Small # of times mentioned in the claims: The alleged contribution is “recited only once in a single claim” whereas the two other independent claims recite preheating with a microwave oven, with no mention of an infrared oven.

- Presence of a more significant alternative in the disclosure: The alternative to the alleged contribution, preheating with a microwave oven, “feature[s] prominently throughout the specification, claims, and figures.”

- Specification focused on the alternative: All the specific examples disclosed in the specification are limited to embodiments using preheating with a microwave oven.

- Drawings focused on the alternative: All the figures, including Figure 1 primarily depicting the operating principles of the claimed invention, are limited to embodiments based on preheating with a microwave oven.

Noting that the entirety of the ’498 patent disclosure supports insignificance in quality of the alleged contribution per the second part of Pannu test, the CAFC concluded that Howard did not qualify as a joint inventor. Lastly, the CAFC noted that there was no need to address the other Pannu factors “as the failure to meet any one factor is dispositive on the question of inventorship.”

Takeaway

This case provides a reminder of the role a patent disclosure may play in determining the question of joint inventorship. In particular, although the second Pannu factor requires the inventor’s contribution to be “not insignificant in quality” (emphasis added), in certain circumstances, the amount of mentions made of the alleged contributed concept in the patent, along with other considerations such as the primary focus of the patent as discerned from the entire disclosure, may influence the determination of joint inventorship.

[1] Hormel’s second main argument challenges insufficiency of corroboration of Howard’s testimony, the question rendered moot due to the decision on the significance of the alleged contribution.

Artificial Intelligence Systems Cannot be Inventors on a Patent Application

| October 5, 2022

Thaler v. Vidal

Decided: August 5, 2022

Moore, Taranto and Stark. Opinion by Stark

Summary:

This case decided the issue of whether an artificial intelligence (AI) software system can be an inventor on a patent application. The USPTO concluded that an inventor is limited to natural persons. The U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia agreed and granted the USPTO summary judgment. The CAFC affirmed the District Court concluding that an inventor must be a natural person.

Details:

Thaler developed the Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Science which is referred to as “DABUS.” DABUS is described as “a collection of source code or programming and a software program.” Thaler filed two patent applications at the USPTO listing DABUS as the sole inventor. Thaler stated that he did not contribute to the conception of the inventions and that any person having skill in the art could have taken DABUS’ output and reduced the ideas in the applications to practice.

For the inventor’s last name, Thaler wrote that “the invention was generated by artificial intelligence.” For the oath/declaration requirement, Thaler submitted a statement on behalf of DABUS. In a Statement on Inventorship, Thaler explained that DABUS was “a particular type of connectionist artificial intelligence” called a “Creativity Machine.” Thaler also filed an assignment assigning all of DABUS’ rights to himself.

The PTO mailed a Notice to File Missing Parts for each application requiring that Thaler identify valid inventors. Thaler petitioned the PTO to vacate the notices. However, the PTO denied the petitions on the ground that “a machine does not qualify as an inventor.” Thaler then challenged the petition decision in District Court. The District Court granted the PTO’s motion for summary judgment concluding that “an ‘inventor’ under the Patent Act must be an ‘individual’ and the plain meaning of ‘individual’ as used in the statute is a natural person.”

Thaler appealed the District Court’s decision to the CAFC. The CAFC stated that “[t]he sole issue on appeal is whether an AI software system can be an ‘inventor’ under the Patent Act. The CAFC first looked to the plain meaning of the Patent Act. The Patent Act defines an “inventor” as “the individual or, if a joint invention, the individuals collectively who invented or discovered the subject matter of the invention.” 35 U.S.C. 100(f). Citing § 115, the CAFC stated that the Patent Act also consistently refers to inventors as “individuals,” and uses personal pronouns “himself” and “herself” to refer to an “individual.” The Patent Act does not define “individuals,” but the CAFC looked to Supreme Court precedent and stated that “as the Supreme Court has explained, when used as a noun, ‘individual’ ordinarily means a human being, a person.

The CAFC also looked to dictionary definitions of “individual” which is defined as a human being. The CAFC also referred to the Dictionary Act which states that “person” and “whoever” broadly include “unless the context dictates otherwise,” “corporations, companies, associations, firms, partnerships, societies, and joint stock companies, as well as individuals.” 1 U.S.C. § 1. The CAFC interprets the Dictionary Act as meaning that Congress understands “individual” to mean natural persons unless otherwise noted.

Thaler argued that the Patent Act uses “whoever” in §§ 101 and 271. With regard to § 101, the CAFC stated that this section uses “whoever,” but § 101 also states that patents must satisfy the “conditions and requirements” of Title 35 of the U.S. Code, including the definition of inventor. Regarding § 271, the CAFC stated that this section refers to infringement, however, “That non-humans may infringe patents does not tell us anything about whether non-humans may also be inventors of patents.”

Thaler also argued that AI software must qualify as inventors because otherwise patentability would depend on “the manner in which the invention was made,” in contravention of 35 U.S.C. § 103. However, the CAFC stated that § 103 is not about inventorship. The cited provision of § 103 refers to how an invention is made, and does not outweigh the statutory provision addressing who may be an inventor.

The CAFC also referred to its own precedent stating that inventors must be natural persons and cannot be corporations or sovereigns. Univ. of Utah v. Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Forderung der Wissenschaften E.V., 734 F.3d 1315, 1323 (Fed. Cir. 2013); Beech Aircraft Corp. v. EDO Corp., 990 F.2d 1237, 1248 (Fed. Cir. 1993).

Thaler also raised some policy arguments stating that “inventions generated by AI should be patentable in order to encourage innovation and public disclosure.” However, the CAFC stated that this is speculative and lacks a basis in the text of the Patent Act and in the record, and anyway, the text in the statue is unambiguous.

The CAFC concluded that the Patent Act unambiguously and directly answers the question regarding whether AI can be an inventor and stated that “Congress has determined that only a natural person can be an inventor, so AI cannot be.”

Comments

According to Thaler, South Africa has granted patents with DABUS as an inventor. However, this will not be possible in the US unless the Supreme Court steps in (which does not seem likely) or Congress amends the Patent Act.

PETITION DENIED: AI MACHINE CANNOT BE LISTED AS AN INVENTOR

| May 21, 2020

In re Application of Application No. 16/524,350 (“Devices and Methods for Attracting Enhanced Attention”)

April 27, 2020

Robert W. Bahr (Deputy Commissioner for Patent Examination Policy)

Summary:

The PTO denied a petition to vacate a Notice to File Missing Parts of Nonprovisional Application because an AI machine cannot be listed as an inventor based on the relevant patent statutes, case laws from the Federal Circuit, and the relevant sections in the MPEP. The PTO did not find the petitioner’s policy arguments persuasive.

Details:

This application was filed on July 29, 2019. Its Application data sheet (ADS) included a single inventor with the given name “DABUS[1]” and the family name “Invention generated by artificial intelligence.” The ADS identified the Applicant as the Assignee “Stephen L. Thaler.” Also, a substitute statement (in lieu of declaration) executed by Mr. Thaler was submitted, and an assignment document executed by Mr. Thaler on behalf of both DABUS and himself was submitted. Finally, an “Inventorship Statement,” which stated that the invention was conceived by “DABUS” and it should be named as the inventor, was also submitted.

Afterward, the PTO issued a first Notice to File Missing Parts on August 8, 2019, which indicated that the ADS “does not identify each inventor by his or her legal name,” and an surcharge of $80 is due for late submission of the inventor’s oath or declaration.

Mr. Thaler filed a petition on August 29, 2019, requesting supervisory review of the first Notice.

The PTO issued a second Notice to File Missing Parts on December 13, 2019. The PTO dismissed the petition filed on August 29, 2019 in a decision issued on December 17, 2019.

Mr. Thaler filed a second petition on January 20, 2020, requesting reconsideration of the decision issued on December 17, 2019.

Relevant Statutes cited by the PTO

35 U.S.C. §100(f):

The term “inventor” means the individual or, if a joint invention, the individuals collectively who invented or discovered the subject matter of the invention.

35 U.S.C. §100(g):

The terms “joint inventor” and “coinventor” mean any 1 of the individuals who invented or discovered the subject matter of a joint invention.

35 U.S.C. §101:

Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.

35 U.S.C. §115(a):

An application for patent that is filed under section 111 (a) or commences the national stage under section 371 shall include, or be amended to include, the name of the inventor for any invention claimed in the application. Except as otherwise provided in this section, each individual who is the inventor or a joint inventor of a claimed invention in an application for patent shall execute an oath or declaration in connection with the application

35 U.S.C. §115(b):

An oath or declaration under subsection (a) shall contain statements that … such individual believes himself or herself to be the original inventor or an original joint inventor of a claimed invention in the application.

35 U.S.C. §115(h)(1):

Any person making a statement required under this section may withdraw, replace, or otherwise correct the statement at any time.

The PTO’s reasoning

Citing the above statutes, the PTO found that the patent statutes preclude the petitioner’s broad interpretation that an “inventor” could be construed to cover machines. That is, the PTO asserted that such broad interpretation could contradict the plain reading of the patent statutes.

The PTO also cited the case law from the Federal Circuit to dismiss the petitioner’s argument. For example, in Univ. of Utah v. Max-Planck-Gesellschajt zur Forderung der Wissenschajten e. V (734 F.3d 1315 (Fed. Cir. 2013), the CAFC held that a state could not be an inventor. In Beech Aircraft Corp. v. EDO Corp. (990 F.2d 1237 (Fed. Cir. 1993), the CAFC held that “only natural persons can be ‘inventor.’”

Furthermore, the PTO cited the relevant sections in the MPEP to support their position. The PTO indicated that the MPEP defines “conception” as “the complete performance of the mental part of the inventive act” and it is “the formation in the mind of the inventor of a definite and permanent idea of the complete and operative invention as it is thereafter to be applied in practice.” The PTO asserted that the use of terms such as “mental” and “mind” indicates that conception must be performed by a natural person.

The PTO rejected the petitioner’s argument that the PTO should take into account the position adopted by the EPO and the UKIPO that DABUS created the invention, but DABUS cannot be named as the inventor. The PTO indicated that the EPO and the UKIPO are interpreting and enforcing their own laws.

The PTO also rejected the petitioner’s argument that inventorship should not be a substantial condition for the grant of patents by arguing that “inventorship has long been a condition for patentability.” The PTO rejected the notion that the granting of a patent for an invention that covers a machine does not mean that the patent statutes allow that machined to be listed as an inventor in another patent application.

Finally, the petitioner provided some policy considerations to support his position: (1) this would incentivize innovation using AI systems, (2) would reduce the improper naming of persons as inventor who do not qualify as inventors, and (3) would inform the public of the actual inventors of an invention. The PTO rejected the petitioner’s policy considerations by arguing that they do not overcome the plain language of the patent statutes.

Takeaway:

- At this point, it appears that it is not possible to list an AI machine as an inventor in the U.S. patent applications. The EPO reached a similar decision in December. It is known that the Japanese Patent Act and the Korean Patent Act do not include an explicit definition of an inventor. Also, the Chinese State Council called for “better IP protections to promote AI.”

- Congress needs to work on this issue because the patent system is in place to incentive innovation in technology, and eventually, increase investment for more jobs.

- A lack of patent protection for inventions developed by AI would decrease investment in the development and use of AI.

- However, there is a concern, among other things, that the PTO may not be able to deal with situations where AI created enormous amount of prior arts to be reviewed by the Examiners.

- Human programmer of AI or the one who defined the task of AI machine could be listed as the named inventor.

[1] DABUS stands for “Device for Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience.” Mr. Thaler asserts that DABUS is a creativity machine programmed as a series of neural networks that have been trained with general information in the field of endeavor to independently create invention. In addition, Mr. Thaler asserts that this machine was “not created to solve any particular problem and not trained on any special data relevant to the instant invention.” Furthermore, Mr. Thaler asserts that this machine recognized “the novelty and salience of the instant invention.”

Tags: 35 U.S.C. §100 > artificial intelligence > conception > DABUS > inventorship > Petition

A Federal Circuit Reminder of the Continued Importance of Laboratory Notebooks and Other Corroborative Evidence of Inventorship

| April 22, 2016

Meng v. Chu

April 5, 2016

Before: Prost, Dyk and Wallach. Opinion by Prost

Summary

In 1987, a research group at the High Pressure Low Temperature (“HPLT”) lab at the University of Houston lead by Ching-Wu Chu, a professor and the lab’s lead investigator, developed inventions related to superconducting compounds having transition temperatures higher than the boiling point of liquid nitrogen. The University of Houston filed two applications listing Chu as the sole inventor. The inventions were assigned to the University of Houston and licensed to Dupont. The University of Houston and Ching-Wu evenly shared the license proceeds received from Dupont, and Chu gave $274,000 from his share to Pei-Herng Hor, a grad student at the lab, and Ruling Meng, an independent scientist at the lab. After issuance of patents for the inventions, in 2008 Hor filed a law suit in the District Court for the Southern District of Texas seeking to be added as a co-inventor and in 2010 Meng intervened seeking to also be added as a co-inventor. The District Court denied both Hor’s and Meng’s claims on the bases that they had failed to meet the “heavy burden” of proving co-inventorship by clear and convincing evidence despite Hor and Meng having received proceeds under the license, having been the first and second listed authors on a publication related to the inventions, and having been commended by Chu in a letter of recommendation for Hor for his discoveries related to the inventions. The Federal Circuit affirmed.

Problems That May Arise When Inventor Changes Employment: Obviousness-type Double Patenting

| March 13, 2013

In Re Jeffery Hubbell

March 7, 2013

Panel: Newman, O’Malley and Wallach. Opinion by O’Malley. Dissent by Newman.

Summary

Most patent practitioners would not be worried about an issued patent having a much later filing date than the application they are prosecuting. However, this case illustrates that such a patent can ultimately bar their application from issuing due to the doctrine of obviousness-type double patenting.

Tags: common assignees > common ownership > double patenting > inventorship > obviousness-type double patenting > terminal disclaimer

A District Court application of Therasense

| February 28, 2013

Caron and Spellbinders Paper Arts Company, LLC vs. QuicKutz, Inc.

United States District Court for the District Of Arizona

November 13, 2012, Decided

SUMMARY

In Therasense, Inc. v. Becton, Dickinson & Company, 649 F.3d 1276 (Fed. Cir. 2011) the CAFC ruled that District Courts must find intent and materiality separately, i.e., weighing the evidence of intent to deceive independently from analysis of materiality.

Here, in one of the few cases since Therasense, a District Court applies separate analyses for each of intent and materiality. In addition, the District Court applied the exception to the but-for materiality requirement in cases of affirmative egregious misconduct.

Knowingly not naming the inventors was held to be inequitable conduct.

Declarations by persons not skilled in the art were held to be inequitable conduct.

Declarations that did not disclose financial relationships with the inventors were held to be inequitable conduct.

A Declaration where the Declarant, when he made the declaration, did not know whether the statements in the declaration were true or not was held to be inequitable conduct.

Tags: but-for test > declaration > egregious conduct > inequitable conduct > inventorship

CAFC Allows Willful Infringer to Continue Infringements for an “Ongoing Royalty” Due to “the Public’s Interest to Allow Competition in the Medical Device Arena”

| February 16, 2012

Bard Peripheral Vascular, Inc., et al. v. W.L. Gore & Associates, Inc.

February 10, 2012

Panel: Gajarsa, Linn and Newman. Opinion by Gajarsa. Dissent by Newman.

Summary

This decision concludes a forty-year-long story that began in 1973 between two cooperating individuals that independently filed patent applications for vascular grafts in 1974. Those applications went to interference in 1983 and have been the subject of ongoing litigation since, concluding now in the current CAFC decision. The Arizona district court from which the present case was appealed expressed that this was “the most complicated case the district court has [ever] presided over.” In this case, the Gore inventor was the first to both 1) conceive of the invention and 2) file a patent application in 1974 (i.e., filing 6 months prior to the Bard inventor), but Gore lost in an interference before the Patent Office. Now, Gore is found to be willfully infringing the patent that was awarded to Bard, and is subjected to doubled damages (i.e., totaling $371 million) and attorney’s fees (i.e., totaling $19 million). However, despite these findings, the CAFC allows Gore to continue infringing, declining a permanent injunction and awarding reasonable royalties in the amount of between 12.5% to 20% for future infringements due to the weight of “the public interest to allow competition in the medical device arena.”

Tags: damages > first-to-file > inventorship > ongoing royalty > permanent injunction > willfulness

Joint Inventorship of a novel compound may exist even if co-inventor only developed method of making

| January 25, 2012

Falana v. Kent State University and Alexander J. Seed

January 23, 2012

Panel: Linn, Prost and Reyna. Opinion by Linn.

Summary

The CAFC held that a putative inventor who envisioned the structure of a novel chemical compound and contributed to the method of making that compound is a joint inventor of a claim covering that compound. One may be a joint inventor even if co-inventor’s contribution to conception is merely a method of making the claimed product and said co-inventor does not synthesize the claimed compound.

Tags: claim construction > damages > exceptional case > inventorship > joint inventorship