The Twists and Turns of Claim Construction Issues in an IPR

| February 2, 2024

Parkervision v. Vidal

Decided: December 20, 2023

Summary:

Although patent owner ParkerVision’s claim construction was adopted in multiple district court litigations, it was not adopted by the PTAB in the IPR of the same patent. The Federal Circuit, reviewing claim construction de novo, affirmed the Board’s final decision. ParkerVision introduced the claim construction issue in its patent owner response, arguing that the claimed “storage element” should be construed as “an element of an energy transfer system that stores non-negligible amounts of energy from an input EM signal” and that the cited prior art did not teach the claimed “storage element” because its allegedly corresponding capacitors were not part of any energy transfer system. Intel filed a reply asserting that the interpretation of a “storage element” does not require it to be part of an energy transfer system. The Board and the Federal Circuit agreed. ParkerVision did not further argue in its patent owner response that the cited prior art’s capacitors failed the requirement that it store “non-negligible” amounts of energy from the input EM signal. ParkerVision included in its sur-reply that the cited prior art’s capacitors stored only a negligible amount of energy because “non-negligible” must be measured relative to the available energy of the input EM signal. The Board granted Intel’s motion to strike this part of ParkerVision’s sur-reply. The court affirmed, noting that there was no abuse of discretion when the Board refused to consider a new theory of patentability raised for the first time in a sur-reply.

Procedural History:

Intel petitioned for inter partes review (IPR) of claim 3 of Parkervision’s USP 7,110,444 (the ‘444 patent). There are related district court litigations involving the ‘444 patent and other related patents, which adopted a claim construction of a “storage element” aligned with Parkervision’s proposed claim construction. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (the Board) adopted Intel’s claim construction of a “storage element” and issued a final decision that the ‘444 patent was obvious over cited prior art. Parkervision appealed. In issuing its final decision, the Board recognized that several district court cases involving the ‘444 patent adopted claim constructions inconsistent with Intel’s proposed construction. See, ParkerVision, Inc. v. Intel Corp., Nos. 6:20-cv-108-ADA, 6:20-cv-562-ADA (W.D. Tex.); ParkerVision, Inc. v. Hisense Co., Nos. 6:20-cv-870-ADA, 6:21-cv-562-ADA (W.D. Tex.); ParkerVision, Inc. v. TCL Indus. Holdings Co., No. 6:20-cv-945-ADA (W.D. Tex.); ParkerVision, Inc. v. LG Elecs. Inc., No. 6:21-cv-520-ADA (W.D. Tex.).

Decision:

Claim 3 of the ‘444 patent is as follows:

A wireless modem apparatus, comprising:

a receiver for frequency down-converting an input signal including,

a first frequency down-conversion module to down-convert the input signal, wherein said first frequency down-conversion module down-converts said input signal according to a first control signal and outputs a first down-converted signal;

a second frequency down-conversion module to down-convert said input signal, wherein said second frequency down-conversion module down-converts said input signal according to a second control signal and outputs a second down-converted signal; and

a subtractor module that subtracts said second down-converted signal from said first down-con-verted signal and outputs a down-converted signal;

wherein said first and said second frequency down-conversion modules each comprise a switch and a storage element.

The ‘444 patent relates to wireless local area networks (WLANs) that use frequency translation technology. In a two-device network using frequency translation, the first device receives a low-frequency baseband signal (audible voice signal) and up-converts it to a high-frequency electromagnetic (EM) signal before wireless transmission to the second device. The second device receives the EM signal, down-converts it back to a low-frequency baseband signal, and outputs an audible signal. The ‘444 patent is directed to down-converting EM signals using down-converter modules that include a switch and a storage element (also called a storage module).

The main issue in this case is the claim construction for a “storage element.”

ParkerVision contends that a “storage element” is an element of an energy transfer system that stores non-negligible amounts of energy from an input EM signal. A magistrate judge’s claim construction order in ParkerVision v. LG and a special master’s recommendation in ParkerVision v. Hisense and in ParkerVision v. TCL adopted ParkerVision’s proposed claim construction.

Intel contends that a “storage element” is “an element of a system that stores non-negligible amounts of energy from an input EM signal” – which does not require that the element be part of an energy transfer system. The Board adopted Intel’s claim construction. The Federal Circuit agreed. This is dispositive in the obviousness holding because ParkerVision’s patent owner response in the IPR focused exclusively on the prior art’s lack of an energy transfer system.

The ‘444 patent incorporated by reference USP 6,061,551 (the ‘551 patent) which provided the following disclosure critical to the meaning of a “storage element”:

1 FIG. 82A illustrates an exemplary energy transfer system 8202 for down-converting an input EM signal 8204. 2 The energy transfer system 8202 includes a switching module 8206 and a storage module illustrated as a storage capacitance 8208. 3 The terms storage module and storage capacitance, as used herein, are distinguishable from the terms holding module and holding capacitance, respectively. 4 Holding modules and holding capacitances, as used above, identify systems that store negligible amounts of energy from an under-sampled input EM signal with the intent of “holding” a voltage value. 5 Storage modules and storage capacitances, on the other hand, refer to systems that store non-negligible amounts of energy from an input EM signal.

(bracketed numbers identifying referenced sentences)

This is deemed “lexicographic” because “as used herein” in sentence #3 refers to the use of these terms (contained throughout the drawings and specification) in general, and not to specific embodiments, and “refer to” in sentence #5 links “storage modules” (parties agreed this is synonymous with “storage element”) to “systems that store non-negligible amounts of energy from an input EM signal.”

ParkerVision’s argued that the ‘551 paragraph was addressing examples in which storage modules are used in energy transfer systems in which holding modules, by contrast, are used in under-sampling systems. The court dismissed this because the comparative nature of the paragraph does not prevent it from being definitional. And, the court refused to incorporate an entire “energy transfer system” into the claim just because a single component (storage element) can be a part of such a system. The court also stated that the district court claim constructions by the magistrate judge and special masters do not alter its conclusion that the Board arrived at the correct construction.

Another, procedural, issue on appeal is whether (1) the Board erred in relying on Intel’s reply (raising this claim construction issue that “storage element” is not limited to being part of an “energy transfer system”) and (2) the Board erred in striking parts of ParkerVision’s sur-reply.

First, ParkerVision asserted that the Board erred in relying on Intel’s arguments allegedly raised for the first time in Intel’s reply. The presumed contention is that the Board deprived ParkerVision of its procedural rights under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) and failed to comply with the USPTO’s rule that a reply “may only respond to arguments raised in the … patent owner response…” 37 C.F.R. § 42.23(b). The court reviews the Board’s compliance with the APA de novo, and the Board’s determination that a party violated USPTO rules for abuse of discretion. Under the APA, the Board must:

“timely inform[]” the patent owner of “the matters of fact and law asserted,” 5 U.S.C. § 554(b)(3), must provide “all interested parties opportunity for the submission and consideration of facts [and] arguments . . . [and] hearing and decision on notice,” id. § 554(c), and must allow “a party . . . to submit rebuttal evidence . . . as may be required for a full and true disclosure of the facts,” id. § 556(d).

Dell Inc. v. Acceleron, LLC, 818 F.3d 1293, 1301 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

Neither petitioner nor patent owner expressly proposed any pre-institution claim construction. Post-institution, ParkerVision first proposed a new claim construction position in its patent owner response wherein “storage element” was construed as “an element of an energy transfer system that stores non-negligible amounts of energy from an input electromagnetic signal.” The APA required the Board to give Intel “adequate notice and an opportunity to respond under the new construction” proffered in ParkerVision’s patent owner response. As in Axonics, Inc. v. Medtronic, Inc., 75 F.4th 1374 (Fed. Cir. 2023), the court held that “where a patent owner in an IPR first proposes a claim construction in a patent owner response, a petitioner must be given the opportunity in its reply to argue and present evidence of anticipation or obviousness under the new construction….” Id. at 1384. Intel did just that. Intel’s reply countered that ParkerVision’s non-obviousness position that the cited prior art did not disclose the claimed “storage element” because it was not in an energy transfer system is misplaced because that term is not restricted to be an element of an energy transfer system.

Pursuant to the APA, the Board may not change theories mid-stream without giving the parties reasonable notice of its change. The Board’s adopting of Intel’s claim construction did not “change theories midstream without giving the parties reasonable notice of its change.” “Once ParkerVision introduced a claim construction argument into the proceeding through its patent owner response, Intel was entitled in its reply to respond to that argument and explain why that construction should not be adopted.” And, ParkerVision had an opportunity to respond to Intel’s proposed construction by filing its sur-reply, which continued to press for its own claim construction.

However, with regard to patentability (non-obviousness), ParkerVision added in its sur-reply, for the first time, that the cited prior art’s capacitors stored only a negligible amount of energy because “non-negligible” must be measured relative to the available energy of the input EM signal. This part of ParkerVision’s sur-reply was stricken by the Board. ParkerVision’s patent owner response asserted that the cited prior art capacitors must store non-negligible amounts of energy, but did not assert that the reference failed to meet that requirement (instead, merely arguing the capacitors are not part of an energy transfer system). Accordingly, its sur-reply offered a new theory of patentability. There is no abuse of discretion in declining to consider a new theory of patentability raised for the first time in sur-reply.

ParkerVision further asserted that its sur-reply arguments addressed allegedly new arguments in Intel’s reply. But, the Board noted:

[I]f [ParkerVision] believed [Intel’s] Reply raised an issue that was inappropriate for a reply brief or that [ParkerVision] needed a greater opportunity to respond beyond that provided by our Rules (e.g., to include new argument and evidence in its Sur-reply), it was incumbent upon [ParkerVision] to contact [the Board] and request authorization for an exception to the Rules. [ParkerVision] did not do so. [ParkerVision] did not request that its Sur-reply be permitted to include arguments and evidence that would otherwise be impermissible in a sur-reply.

The court faulted ParkerVision for not availing itself of the available procedural mechanisms. For these reasons, the court found no abuse of discretion in the Board’s exclusion of part of ParkerVision’s sur-reply.

Takeaways:

The existence of district court claim construction positions do not guarantee the same claim constructions being adopted by the Board. And, the Federal Circuit reviews claim construction issues de novo.

For the patent owner’s sur-reply, be wary of potentially “new” patentability positions being advanced that were not originally raised in the patent owner response. If any such “new” patentability positions are taken, be cognizant of the procedural mechanism to contact the Board and request authorization for an exception to the Rules to include arguments and/or evidence that may otherwise be impermissible in a sur-reply.

THE PTAB’S IPR INSTITUTION DECISION IS FINAL AND NONAPPEALABLE

| April 6, 2021

CyWee Group LTD. v. Google LLC

Summary:

CyWee appealed the PTAB’s final decision on three grounds. First, CyWee argued that the PTAB erred in concluding that Google disclosed all real parties in interest. However, the CAFC noted that the CAFC is precluded from reviewing this challenge because the PTAB’s determination on this issue is final and nonappealable. Second, CyWee argued that the CAFC should terminate and dismiss the IPR proceedings because the APJs were appointed in violation of the Appointments Clause. The CAFC rejected this challenge because the APJs were constitutionally appointed as of the date that the Arthrex decision was issued. Finally, a prior cited by Google (Bachmann) is not an analogous art. However, the CAFC held that Bachmann is reasonably pertinent to the particular problem with which the inventor is involved, and that this reference does not have to be reasonably pertinent to every problem facing a field to be analogous prior art. Therefore, the CAFC affirmed that the PTAB’s determination that the challenged claims would have been obvious in view of Bachmann.

Details:

Google LLC (“Google”) petitioned for IPR of claims 1 and 3-5 of U.S. Patent No. 8,441,438 and claims 10 and 12 of U.S. Patent No. 8,552,978, asserting that those claims are unpatentable as obvious in view of U.S. Patent No. 7,089,148 (“Bachmann”).

The PTAB instituted IPR and found that those claims would have been obvious. CyWee appeals.

CyWee’s first argument

CyWee argues that the PTAB erred in concluding that Google disclosed all real parties in interest, as required by 35 U.S.C. §312(a)(2)[1].

The CAFC found that the CAFC is precluded from reviewing this challenge because the PTAB’s determination on this issue is final and nonappealable under 35 U.S.C. §314(d)[2] because this issue “raises an ordinary dispute about the application of an institution-related statute.”

CyWee argued that CyWee attempts to challenge the PTAB’s denial of CyWee’s post-institution motion to terminate the proceedings in view of newly found evidence.

However, the CAFC found that CyWee’s request is nothing more than a request for the PTAB to reconsider its institution decision, which is final and nonappealable.

CyWee’s second argument

CyWee argues that the CAFC should terminate and dismiss the IPR proceedings because the APJs were appointed in violation of the Appointments Clause.

However, the CAFC rejected this challenge because the APJs were constitutionally appointed as of the date that the Arthrex decision[3] was issued, and because the Arthrex decision was issued before the final decisions in this case. Therefore, the CAFC found that those final decisions were rendered by constitutional panels.

CyWee’s third argument

CyWee argues that Bachmann is not an analogous art.

However, the CAFC found that the PTAB’s conclusion is supported by substantial evidence because the PTAB determined that (1) “improving error compensation with an enhanced comparison method” was of “central importance” to the inventors, and that (2) Bachmann was reasonably pertinent to this problem because Bachmann “illustrates collection of data from the same kinds of sensors” and “correct[s] for the same kinds of errors that were of concern to the inventor[s].”

Therefore, the CAFC found that Bachmann is reasonably pertinent to the particular problem with which the inventor is involved.

Furthermore, the CAFC noted that a reference need not be reasonably pertinent to every problem facing a field to be analogous prior art, but rather need only be “reasonably pertinent to one or more of the particular problems to which the claimed inventions relate.” Donner Tech., LLC v. Pro Stage Gear, LLC, 979 F.3d 1353, 1361 (Fed. Cir. 2020).

Finally, the CAFC noted that “a reference can be analogous art with respect to a patent even if there are significant differences between the two references.” Donner, 979 F.3d at 1361.

Takeaway:

- The PTAB’s decision on whether to institute an IPR proceeding is final and nonappealable.

- The Supreme Court heard the oral argument in the Arthrex case on March 1, 2021. Two questions before the Court are (1) whether APJs are properly appointed, and (2) if they are not properly appointed, whether removing employment protections corrects the defect.

- A reference need not be reasonably pertinent to every problem facing a field to be analogous prior art, but rather need only be “reasonably pertinent to one or more of the particular problems to which the claimed inventions relate.” A reference can be analogous art with respect to a patent even if there are significant differences between the two references.

[1] 35 U.S. Code § 312 – Petitions

(a) Requirements of Petition. – A petition filed under section 311 may be considered only if –

(2) the petition identifies all real parties in interest;

[2] 35 U.S. Code § 314 – Institution of inter partes review

(d) No Appeal. – The determination by the Director whether to institute an inter partes review under this section shall be final and nonappealable.

[3] Arthrex, Inc. v. Smith & Nephew, Inc., 941 F.3d 1320 (Fed. Cir. 2019): “The APJs were actually “principal officers” under the Appointments Clause, and that the APJ appointment provisions of the AIA creating the PTAB were unconstitutional because the APJs were not appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate, as is required for “principal officers.””

Tags: administrative patent judge > Analogous Art > appointment clause > inter partes review > real party in interest

New evidence submitted with a reply in IPR institution proceedings

| December 30, 2020

VidStream LLC v. Twitter, Inc.

November 25, 2020

Newman, O’Malley, and Taranto. Court opinion by Newman.

Summary

On appeals from the United States Patent and Trademark Office in IPR arising from two petitions filed by Twitter, the Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s ruling that Bradford is prior art (printed publication) against the ’997 patent where the priority date of the ’997 patent is May 9, 2012 and a page of the copy of Bradford cited in Twitter’s petitions stated, in relevant parts, “Copyright © 2011 by Anselm Bradford and Paul Haine” and “Made in the USA Middletown, DE 13 December 2015.” The Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s admission of new evidence regarding Bradford submitted by Twitter in reply (not included in petitions). The Federal Circuit also affirmed the Board’s rulings of unpatentability of claims 1– 35 of the ’997 patent over Bradford and other prior art references, in the two IPR decisions on appeal.

Details

I. background

U.S. Patent No. 9,083,997 (“the ’997 patent”), assigned to VidStream LLC, is directed to “Recording and Publishing Content on Social Media Websites.” The priority date of the ’997 patent is May 9, 2012.

Twitter filed two petitions for inter partes review (“IPR”), with method claims 1–19 of the ’997 patent in one petition, and medium and system claims 20–35 of the ’997 patent in the other petition. Twitter cited Bradford as the primary reference for both petitions, combined with other references.

With the petitions, Twitter filed copies of several pages of the Bradford book, and explained their relevance to the ’997 claims. Twitter also filed a Bradford copyright page that contains the following legend:

Copyright © 2011 by Anselm Bradford and Paul Haine

ISBN-13 (pbk): 978-1-4302-3861-4

ISBN-13 (electronic): 978-1-4302-3862-1

A page of the copy of Bradford cited in Twitter’s petitions also states:

Made in the USA

Middletown, DE

13 December 2015

VidStream, in its patent owner’s response, argued that Bradford is not an available reference because it was published December 13, 2015.

Twitter filed replies with additional documents, including (i) a copy of Bradford that was obtained from the Library of Congress, marked “Copyright © 2011” (this copy did not contain the “Made in the USA Middletown, DE 13 December 2015” legend); and (ii) a copy of Bradford’s Certificate of Registration that was obtained from the Copyright Office and contains following statements:

Effective date of registration: January 18, 2012

Date of 1st Publication: November 8, 2011

“This Certificate issued under the seal of the Copyright Office in accordance with title 17, United States Code, attests that registration has been made for the work identified below. The information on this certificate has been made a part of the Copyright Office records.”

Twitter also filed following declarations:

The Declaration of “an expert on library cataloging and classification,” Dr. Ingrid Hsieh-Yee, who declared that Bradford was available at the Library of Congress in 2011 with citing a Machine-Readable Cataloging (“MARC”) record that was created on August 25, 2011 by the book vendor, Baker & Taylor Incorporated Technical Services & Product Development, adopted by George Mason University, and modified by the Library of Congress on December 4, 2011.

the Declaration of attorney Raghan Bajaj, who stated that he compared the pages from the copy of Bradford submitted with the petitions, and the pages from the Library of Congress copy of Bradford, and that they are identical.

Twitter further filed copies of archived webpages from the Internet Archive, showing the Bradford book listed on a publicly accessible website (http://www.html5mastery.com/) bearing the website date November 28, 2011, and website pages dated December 6, 2011 showing the Bradford book available for purchase from Amazon in both an electronic Kindle Edition and in paperback.

VidStream filed a sur-reply challenging the timeliness and the probative value of the supplemental information submitted by Twitter.

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB” or “Board”) instituted the IPR petitions, found that Bradford was an available reference, and held claims 1–35 unpatentable in light of Bradford in combination with other cited references. Regarding Bradford, the Board discussed all the materials that were submitted, and found:

“Although no one piece of evidence definitively establishes Bradford’s public accessibility prior to May 9, 2012, we find that the evidence, viewed as a whole, sufficiently does so. In particular, we find the following evidence supports this finding: (1) Bradford’s front matter, including its copyright date and indicia that it was published by an established publisher (Exs. 1010, 1042, 2004); (2) the copyright registration for Bradford (Exs. 1015, 1041); (3) the archived Amazon webpage showing Bradford could be purchased on that website in December 2011 (Ex. 1016); and (4) Dr. Hsieh-Yee’s testimony showing creation and modification of MARC records for Bradford in 2011.”

VidStream timely appealed.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit unanimously affirmed all aspects of the Board’s holdings including Bradford being prior art (printed publication).

The critical issue on this appeal is whether Bradford was made available to the public before May 9, 2012, the priority date of the ’997 patent.

Admissibility of Evidence – PTAB Rules and Procedure

VidStream argued that Twitter was required to include with its petitions all the evidence on which it relies because the PTO’s Trial Guide for inter partes review requires that “[P]etitioner’s case-in-chief” must be made in the petition, and “Petitioner may not submit new evidence or argument in reply that it could have presented earlier.” Trial Practice Guide Update, United States Patent and Trademark Office 14–15 (Aug. 2018), https://www.uspto.gov/sites/de- fault/files/documents/2018_Revised_Trial_Practice_Guide. pdf.

Twitter responded that the information filed with its replies was appropriate in view of VidStream’s challenge to Bradford’s publication date, and that this practice is permitted by the PTAB rules and by precedent, which states: “[T]he petitioner in an inter partes review proceeding may introduce new evidence after the petition stage if the evidence is a legitimate reply to evidence introduced by the patent owner, or if it is used to document the knowledge that skilled artisans would bring to bear in reading the prior art identified as producing obviousness.” Anacor Pharm., Inc. v. Iancu, 889 F.3d 1372, 1380–81 (Fed. Cir. 2018).

The Federal Circuit sided with Twitter, concluding that the Board acted appropriately, for the Board permitted both sides to provide evidence concerning the reference date of the Bradford book, in pursuit of the correct answer.

The Bradford Publication Date

VidStream argued that, even if Twitter’s evidence submitted in reply were considered, the Board did not link the 2015 copy of Bradford with the evidence purporting to show publication in 2011, i.e., the date of copyright registration, the archival dates for the Amazon and other webpages, and the date the MARC records were created. VidStream argued that the Board did not “scrutiniz[e] whether those documents actually demonstrated that any version of Bradford was publicly accessible at that time.” VidStream states that Twitter did not meet its burden of showing that Bradford was accessible prior art.

Twitter responded that that the evidence established the identity of the pages of Bradford filed with the petitions and the pages from the copy of Bradford in the Library of Congress. Twitter explains that the copy “made” on December 13, 2015 was a reprint, for the 2015 copy has the same ISBN as the Library of Congress copy, as is consistent with a reprint, not a new edition.

After citing arguments of both parties, the Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s ruling that Bradford is prior art against the ’997 patent because “[t]he evidence well supports the Board’s finding that Bradford was published and publicly accessible before the ’997 patent’s 2012 priority date.” There is no more explanation than this for the affirmance.

Obviousness Based on Bradford

The Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s rulings of unpatentability of claims 1– 35 of the ’997 patent, in the two IPR decisions on appeal because VidStream did not challenge the Board’s decision of obviousness if Bradford is available as a reference.

Takeaway

· Although all relevant evidence should be submitted with an IPR petition, new evidence submitted with a reply may have chance to be admitted if the new evidence is a legitimate reply to the evidence introduced by a patent owner, or if it is used to document the knowledge that skilled artisans would bring to bear in reading the prior art identified as producing obviousness.

FACEBOOK’S IPRs CAN’T FRIEND EACH OTHER

| April 10, 2020

FACEBOOK, INC. v. WINDY CITY INNOVATIONS, LLC.

March 18, 2020

Prost, Plager and O’Malley (Opinion by Prost)

Summary: Plaintiff/Patent Holder Windy Citysuccessfully cross-appealed against Facebook on the issue of improper joinder of IPRs under 35 U.S.C. § 315(c). Facebook had filed IPRs within one year of Windy City’s District Court complaint and then joined later filed IPRs adding new claims. The PTAB had allowed the joinder. The CAFC vacated the Board’s joinder finding that Facebook could not join their own already filed IPRs.

Background:

In June 2016, exactly one year after being served with Windy City’s complaint for infringement of four patents related to methods for communicating over a computer-based net-work, Facebook timely petitioned for inter partes review (“IPR”) of several claims of each patent. At that time, Windy City had not yet identified the specific claims it was asserting in the district court proceeding. The four patents totaled 830 claims. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) instituted IPRs of each patent.

In January 2017, after Windy City had identified the claims it was asserting in the district court litigation, Facebook filed two additional petitions for IPR of additional claims of two of the patents. Facebook concurrently filed motions for joinder to the already instituted IPRs on those patents. By the time of filing the new IPRs, the one-year time bar of §315(b) had passed. The Board nonetheless instituted Facebook’s two new IPRs, and granted Facebook’s motions for joinder.

The Board agreed with Facebook that Windy City’s district court complaint generally asserting the “claims” of the asserted patents “cannot reasonably be considered an allegation that Petitioner infringes all 830 claims of the several patents asserted.” The Board therefore found that Facebook could not have reasonably determined which claims were asserted against it within the one-year time bar. Once Windy City identified the asserted claims after the one-year time bar, the Board found that Facebook did not delay in challenging the newly asserted claims by filing the second petitions with the motions for joinder.

The Board found that Facebook had shown by a preponderance of the evidence that some of the challenged claims are unpatentable, many of these claims had only been challenged in the later filed and joined IPRs. Facebook appealed and Windy City cross-appealed on the Board’s obviousness findings. Further, Windy City also challenged the Board’s joinder decisions allowing Facebook to join its new IPRs to its existing IPRs and to include new claims in the joined proceedings. Windy City’s cross-appeal on the joinder issue is addressed here.

Discussion:

In its cross-appeal, Windy City argued that the Board’s decisions granting joinder were improper on the basis that 35 U.S.C. § 315(c): (1) does not permit a person to be joined as a party to a proceeding in which it was already a party (“same-party” joinder); and (2) does not permit new issues to be added to an existing IPR through joinder (“new issue” joinder), including issues that would otherwise be time-barred.

Sections 315(b) and (c) recite:

(b) Patent Owner’s Action. —An inter partes review may not be instituted if the petition requesting the proceeding is filed more than 1 year after the date on which the petitioner, real party in interest, or privy of the petitioner is served with a complaint alleging infringement of the patent. The time limitation set forth in the preceding sentence shall not apply to a request for joinder under subsection (c).

(c) Joinder. —If the Director institutes an inter partes review, the Director, in his or her discretion, may join as a party to that inter partes review any person who properly files a petition under section 311 that the Director, after receiving a preliminary response under section 313 or the expiration of the time for filing such a response, determines warrants the institution of an inter partes review under section 314.

The CAFC noted that §315(b) articulates the time-bar for when an IPR “may not be instituted.” 35 U.S.C. §315(b). But §315(b) includes a specific exception to the time bar, namely “[t]he time limitation . . . shall not apply to a request for joinder under subsection (c).”

Regarding the propriety of Facebooks joinder, the Court held the plain language of §315(c) allows the Director “to join as a party [to an already instituted IPR] any person” who meets certain requirements. However, when the Board instituted Facebook’s later petitions and granted its joinder motions, the Board did not purport to be joining anyone as a party. Rather, the Board understood Facebook to be requesting that its later proceedings be joined to its earlier proceedings. The CAFC concluded that the Boards interpretation of §315(c) was incorrect because their decision authorized two proceedings to be joined, rather than joining a person as a party to an existing proceeding.

Section 315(c) authorizes the Director to “join as a party to [an IPR] any person who” meets certain requirements, i.e., who properly files a petition the Director finds warrants the institution of an IPR under § 314. No part of § 315(c) provides the Director or the Board with the authority to put two proceedings together. That is the subject of § 315(d), which provides for “consolidation,” among other options, when “[m]ultiple proceedings” involving the patent are before the PTO.35 U.S.C. § 315.

The Court went on to explain that the clear and unambiguous language of § 315(c) confirms that it does not allow an existing party to be joined as a new party, noting that subsection (c) allows the Director to “join as a party to [an IPR] any person who” meets certain threshold requirements. They noted that it would be an extraordinary usage of the term “join as a party” to refer to persons who were already a party. Finding the phrase “join as a party to a proceeding” on its face limits the range of “person[s]” covered to those who, in normal legal discourse, are capable of being joined as a party to a proceeding (a group further limited by the own-petition requirements), and an existing party to the proceeding is not so capable.

Regarding the second issue raised by Windy City that the Joinder cannot include newly raised issues, the CAFC found the language in §315(c) does no more than authorize the Director to join 1) a person 2) as a party, 3) to an already instituted IPR. Finding this language does not authorize the joined party to bring new issues from its new proceeding into the existing proceeding, particularly when those new issues are other-wise time-barred.

The Court noted that under the statute, the already-instituted IPR to which a person may join as a party is governed by its own petition and is confined to the claims and grounds challenged in that petition.

In reaching these conclusions, the Court did acknowledge the rock and hard place Facebook is left in.

We do not disagree with Facebook that the result in this particular case may seem in tension with one of the AIA’s objectives for IPRs “to provide ‘quick and cost effective alternatives’ to litigation in the courts.” [Citations omitted] Indeed, it is fair to assume that when Congress imposed the one-year time bar of § 315(b), it did not explicitly contemplate a situation where an accused infringer had not yet ascertained which specific claims were being asserted against it in a district court proceeding before the end of the one-year time period. We also recognize that our analysis here may lead defendants, in some circumstances, to expend effort and expense in challenging claims that may ultimately never be asserted against them.

However, the Court gave little remedy to bearing an enormous “effort and expense” of filing IPRs to 830 claims, asserting that they are bound by the unambiguous nature of the statute.

Petitioners who, like Facebook, are faced with an enormous number of asserted claims on the eve of the IPR filing deadline, are not without options. As a protective measure, filing petitions challenging hundreds of claims remains an available option for accused infringers who want to ensure that their IPRs will challenge each of the eventually asserted claims. An accused infringer is also not obligated to challenge every, or any, claim in an IPR. Accused infringers who are unable or unwilling to challenge every claim in petitions retain the ability to challenge the validity of the claims that are ultimately asserted in the district court. Accused infringers who wish to protect their option of proceeding with an IPR may, moreover, make different strategy choices in federal court so as to force an earlier narrowing or identification of asserted claims. Finally, no matter how valid, “policy considerations cannot create an ambiguity when the words on the page are clear.” SAS, 138 S. Ct. at 1358. That job is left to Congress and not to the courts.

Hence, the CAFC concluded that the clear and unambiguous language of §315(c) does not authorize same-party joinder, and also does not authorize joinder of new issues, including issues that would otherwise be time-barred. As a result, they vacated the Board’s decisions on all claims which were asserted in the later filed IPRs.

Take Away: A loop-hole between the one-year time bar, joinder statute for IPRs and District Court timing potentially gives a Plaintiff/Patent holder the ability to render an IPR more cost inefficient to a Defendant/Petitioner. By not identifying the claims to be asserted within one year of filing a patent infringement complaint, the patent holder can place a large burden on filing an IPR. Plaintiffs/Patent holders can strategize to assert infringement ambiguously to a prohibitive number of claims early in a District Court proceeding. Defendants will need to attempt to counter such a strategy by requesting District Courts to force Plaintiffs to identify the specific claims which will be asserted within one year of filing the complaint.

GENERAL KNOWLEDGE OF A SKILLED ARTISAN COULD BE USED TO SUPPLY A MISSING CLAIM LIMITATION FROM THE PRIOR ART WITH EXPERT EVIDENCE IN THE OBVIOUSNESS ANALYSIS

| February 5, 2020

Koninklijke Philips N.V. v. Google LLC, Microsoft Corporation, Microsoft Mobile Inc.

January 30, 2020

Summary:

The Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s final decision that claims of Philips’ ‘806 patent are unpatentable as obvious. The Federal Circuit held that the PTAB did not err in relying on general knowledge to supply a missing claim limitation in the IPR if the PTAB relied on expert evidence corroborated by a cited reference. The Federal Circuit also held that the PTAB did not have discretion to institute the IPR on the grounds not advanced in the petition.

Details:

The ‘806 Patent

Philips’ ‘806 patent is directed to solving a conventional problem where the user cannot play back the digital content until after the entire file has finished downloading. Also, the ‘806 patent states that streaming requires “two-way intelligence” and “a high level of integration between client and server software,” thereby excluding third parties from developing software and applications.

The ‘806 patent offers a solution that reduces delay by allowing the media player download the next portion of a media presentation concurrently with playback of the previous portion.

Representative claim 1 of the ‘806 patent:

1. A method of, at a client device, forming a media presentation from multiple related files, including a control information file, stored on one or more server computers within a computer network, the method comprising acts of:

downloading the control information file to the client device;

the client device parsing the control information file; and based on parsing of the control information file, the client device:

identifying multiple alternative flies corresponding to a given segment of the media presentation,

determining which files of the multiple alternative files to retrieve based on system restraints;

retrieving the determined file of the multiple alternative files to begin a media presentation,

wherein if the determined file is one of a plurality of files required for the media presentation, the method further comprises acts of:

concurrent with the media presentation, retrieving a next file; and

using content of the next file to continue the media presentation.

PTAB

Google filed a petition for IPR with two grounds of unpatentability. First, claims of the ‘806 patent are anticipated by SMIL 1.0 (Synchronized Multimedia Integration Language Specification 1.0). Second, claims of the ‘806 patent would have been obvious in view of SMIL 1.0 in view of the general knowledge of the skilled artisan regarding distributed multimedia presentation systems as of the priority date. Google cited Hua (2PSM: An Efficient Framework for Searching Video Information in a Limited-Bandwidth Environment, 7 Multimedia Systems 396 (1999)) and an expert declaration to argue that pipelining was a well-known design technique, and that a skilled artisan would have been motivated to use pipelining with SMIL.

The PTAB instituted review on three grounds (including two grounds raised by Google and additional ground). In other words, the PTAB exercised its discretion and instituted an IPR on the additional ground that claims would have been obvious over SMIL 1.0 and Hua based on the arguments and evidence presented in the petition.

In the final decision, the PTAB concluded that while Google had not demonstrated that claims were anticipated, Google had demonstrated that claims would have been obvious in view of SMIL 1.0 and that they would have been obvious in view of SMIL 1.0 in view of Hua as well.

CAFC

First, the CAFC held that the PTAB erred by instituting IPR reviews based on a combination of prior art references not presented in Google’s petition. Citing 35 U.S.C. § 314(b) (“[t]he Director shall determine whether to institute an inter partes review . . . pursuant to a petition”), the CAFC held that it is the petition, not the Board’s discretion, that defines the metes and bounds of an IPR.

Second, the CAFC held that while the prior references that can be considered in IPR are limited patents and printed publications only, it does not mean that the skilled artisan’s knowledge should be ignored in the obviousness inquiry. Distinguishing this case from Arendi (where the CAFC held that the PTAB erred in relying on common sense because such reliance was based merely upon conclusory statements and unspecific expert testimony), the CAFC held that the PTAB correctly relied on expert evidence corroborated by Hua in concluding that pipelining is within the general knowledge of a skilled artisan.

Third, with regard to Philips’ arguments that the PTAB’s combination fails because the basis for the combination rests on the patentee’s own disclosure, the CAFC held that the PTAB’s reliance on the specification was proper and that it is appropriate to rely on admissions in the specification for the obviousness inquiry. The CAFC held that the PTAB supported its findings with citations to an expert declaration and the Hua reference. Therefore, the CAFC found that the PTAB’s factual findings underlying its obviousness determination are supported by substantial evidence.

Accordingly, the CAFC affirmed the PTAB’s final decision that claims of the ‘806 patent are unpatentable as obvious.

Takeaway:

- In the obviousness analysis, the general knowledge of a skilled artisan could be used to supply a missing claim limitation from the prior art with expert evidence.

- Patentee’s own disclosure and admission in the specification could be used in the obviousness inquiry. Patent drafters should be careful about what to write in the specification including background session.

- Patent owners should check whether the PTAB instituted IPR on the grounds not advanced in the IPR petition because the PTAB does not discretion to institute IPR based on grounds not advanced in the petition.

Tags: anticipation > General Knowledge > inter partes review > obviousness > Petition > Skilled Artisan

A Claimed Range May be Anticipated and/or Obviousness When the Lower Limit of the Range of the Reference Abuts the Upper limit of the Disputed Claim Range

| January 31, 2020

Genentech, Inc., v. Hospira, Inc.

Prost, Newman and Chen. Opinion by Chen; Dissenting opinion by Newman.

Summary

At an inter partes review (IPR) proceeding, the Board held that a reference that discloses a range where the lower limit of said range abuts the upper limit of the disputed claim range was sufficient to render the disputed patent invalid for anticipation and obviousness. The Majority Opinion of the CAFC affirmed the holding of anticipation and obviousness. The Dissenting Opinion held that there was insufficient evidence to establish anticipation, the wrong reasoning was used to establish obviousness and the findings of Board and the Majority Opinion were based on hindsight.

Details

Background

Protein A affinity chromatography is a purification method, wherein “a composition comprising a mixture of the target antibody and undesired impurities often present in harvested cell culture fluid (HCCF) is placed into the chromatography column…. The target antibody binds to protein A, which is covalently bound to the chromatography column resin, while the impurities and rest of the composition pass through the column…. Next, the antibody of interest is removed from the chromatography column….” Id. at 3. A known problem of protein A affinity chromatography is leaching, wherein protein A detaches from the column and contaminates the purified antibody solution. Thus, further purification steps of the antibody solution retrieved from the column are necessary. Patent 7,807,799 (hereinafter “‘799”), owned by Genentech, addresses the known problem of protein A leaching, with regards to antibodies and other proteins that comprises a CH2/CH3 region. By reducing the temperature of the composition that is subjected to chromatography, leaching can be prevented and/or minimized to an acceptable level of impurity for commercial purposes. Claim 1, herein presented below, is the representative claim.

A method of purifying a protein which comprises CH2/CH3 region, comprising subjecting a composition comprising said protein to protein A affinity chromatography at a temperature in the range from about 10°C to about 18°C.

See Patent ‘799, Col. 35, Lines 44-47.

IPR

Hospira sought an inter partes review (IPR) of claims 1-3 and 5-11 of Patent ‘799. The Board instituted a trial of unpatentability and held that WO95/22389 (hereinafter “WO ‘389) anticipated and WO ‘389, both solely and in combination with secondary references, rendered obvious all of the challenged claims.

WO ‘389 discloses a method for purifying similar antibodies by a protein A affinity chromatography step and then a washing step, comprising washing with at least three column volumes of buffer. WO ‘389 discloses that “[a]ll steps are carried out at room temperature (18-25oC).” Id. at 6.

The Board held that WO ‘389 overlaps the claimed range of “about 10oC to about 18oC”, regardless of the claim construction of “about 18oC”. Further, the Board held that Genentech failed to establish the criticality of the claimed range to the operability of the claimed invention and thus did not overcome the prima facie case of anticipation. Also, the Board held that the claimed temperature range was in reference to the temperature of the composition both prior to and/or during chromatography. The Board held that the disclosed temperature range (18-25oC) of WO ‘389 applied to all components of the purification process and that the temperature of the HCCF composition both prior to and during chromatography were within said range.

Genentech appealed the Board’s holding of unpatentable due to anticipation and obviousness over WO ‘389. Of note, in the Appeal, Genentech did not challenge the Board’s holding that criticality of the claimed temperature range was not established.

CAFC

Anticipation

Genentech argued that the meaning of “all steps are carried out at room temperature (18-25oC)” is applicable only to the temperature of the laboratory and is not applicable to the temperature of the HCCF composition. Genentech asserted that 1) WO ‘389 discloses “steps” where the HCCF composition was cold or frozen, 2) Genentech’s expert and Hospira’s expert testified that typically HCCF coming from a bioreactor, are at a temperature of 37oC, 3) both experts testified WO ‘389 is silent regarding how long HCCF was held prior to chromatography and 4) Genentech’s expert testified that a skilled artisan in industrial processing would perform chromatography of the HCCF as soon as possible, i.e. without waiting for the HCCF to cool to room temperature, unless there were explicit instructions to do so. Id. at 8. Hospira argued that the explicit disclosure of “room temperature (18-25oC)” is with regards to the temperature of performing chromatography and all the components of said purification process, including the HCCF composition. Hospira noted that WO ‘389 disclosed specific temperatures for when the composition was not at room temperature. Further, Hospira’s expert testified that a skilled artisan would perform experiments at “ambient temperature with all materials equilibrated in order to obtain robust scientific data.” Id. at 9. The CAFC affirmed the Board and held that there was substantial evidence that the HCCF composition was within the claimed temperature of “about 10oC to about 18oC.” The CAFC agreed with the Board’s findings that 1) the statement “[a]ll steps are carried out at room temperature (18-25oC)” was a blanket statement and thus, specifying the temperature of HCCF during chromatography is redundant, 2) it disagreed with Genentech’s expert because said opinion was based upon large-scale industrially standards, and 3) it agreed with Hospira’s expert that a skilled artisan would not use HCCF at 37oC in a chromatography column and then report that all steps were performed at room temperature because the warm HCCF would raise the temperature of the entire system. Id. at 10. Lastly, the CAFC disagreed with Genentech’s argument that there was no anticipation because there was a missing limitation in WO ‘389 and agreed with the Board’s finding that WO ‘389 discloses a composition that is at the claimed temperature of “about 10oC to about 18oC” either prior to or during chromatography. (Nidec Motor Corp. v. Zhongshan Board Ocean Motor Co., cited by Genentech, holds that a reference missing a limitation cannot anticipate even if a skilled artisan would ‘at once envisage’ the missing limitation. 851 F.3d 1270, 1274–75 (Fed. Cir. 2017).” Id. at 10.)

Obviousness

The Board, citing the secondary references, determined that the temperature at which chromatography is performed is a result-effective variable and that when temperature is lowered, leaching is reduced. Thus, a skilled artisan would have been motivated to optimize temperature. Genentech argued that there was no reason or motivation to optimize the temperature because “the desire to reduce protein A leaching applies only to the large-scale, industrial purification of therapeutic antibodies for clinical applications…[and] that chilling HCCF for largescale, industrial processes would have been inconvenient, costly, and impractical.” Id. at 13. Hospira argued that a skilled artisan in non‑clinical applications would have been motivated to reduce leaching because leaching damages chromatography columns. The CAFC held that the Board was correct in holding that neither the ‘799 patent nor WO ‘389 are limited to large-scale industrial applications. The CAFC affirmed the Boards’ finding that temperature is a “result-effective variable” and that it would have been routine experimentation for a skilled artisan to optimize the temperature to reduce protein A leaching.

Dissent

Newman dissented and asserted that affirming the holding of invalidity for anticipation and obviousness was an error because none of the prior art shows or suggest the claimed method. Id. at 9. According to Newman, the determination by the Board and the CAFC is based on hindsight. Newman noted that the “retrospective simplicity of the solution apparently led the Board to find it obvious to them, despite the undisputed testimony that no reference suggests this solution to the contamination problem here encountered, as the experts for both sides acknowledged.” Id. at 3. Newman noted that the ‘799 patent disclosed in detail the complexities with regards to obtaining and purifying antibodies, the many factors to consider when performing chromatography, the problems associated with the leaching of protein A, and explained their discovery of the cause of said leaching and their solution to said problem. At the Board, Genentech argued the advantages of their claimed method, i.e. prevent leaching of protein A in protein A affinity chromatography, in contrast to the need to perform additional purification chromatography to remove protein A, as in WO ‘389. Both experts agreed that the reference to room temperature (18-25oC) was in reference to the ambient temperature and was not in reference to the chilled material in the column. “Nonetheless, the PTAB and now my colleagues hold that this ‘room temperature’ range anticipates the ‘799 patent’s chilled range of 10oC-18oC, ignoring the significantly different results in the recited ranges.” Id. at 6.

According to Newman, mere abutment of the 18oC is not anticipation. “Anticipation requires that the same invention, including all claim limitations, was previously described. Nidec Motor Corp. v. Zhongshan Broad Ocean Motor Co., 851 F.3d 1270, 1274– 75 (Fed. Cir. 2017). The “anticipating reference must describe the entirety of the claimed subject matter.” Id. at 7. Newman holds that the affirmation of anticipation fails to consider the “absence of identify of these ranges” (18-25oC vs. about 10oC-about 18oC), fails to consider “the different results at the lower range” and fails to consider “the significance of the purity of the eluted antibody.” Id. at 8 Regarding obviousness, Newman holds that there is no evidence that it was known or suggested that cooling the HCCF composition either prior to or during chromatography would minimize or prevent leaching of the protein A in the purified antibody solution. According to Newman, “the question is not whether it would have been easy to cool the material to the 10ºC–18ºC range; the question is whether it would have been obvious to do so. Contrary to the Board’s and the court’s view, this is not a matter of optimizing a known procedure to obtain a known result; for it was not known that cooling the material for chromatography would avoid contamination of the purified antibody with leached protein A.” Id. at 9. That is, even if it is possible to modify the temperature, Newman asserts that there is no reason or motivation to optimize the temperature to prevent leaching of protein A.

Takeaway

- If possible, establish the criticality of a claimed range. One is encouraged to rebut a prima facie case of anticipation or obviousness by establishing that the claimed range is critical to the operability of the claimed invention.

- If there is an overlap of a disputed claim range and the range disclosed in the prior art, but the results are different, this may be evidence of the criticality of the range.

A Good Fry: Patent on Oil Quality Sensing Technology for Deep Fryers Survives Inter Partes Review

| October 4, 2019

Henny Penny Corporation v. Frymaster LLC

September 12, 2019

Before Lourie, Chen, and Stoll (Opinion by Lourie)

Summary

In an appeal from an inter partes review, the Federal Circuit affirmed the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s decision to uphold the validity of a patent relating to oil quality sensing technology for deep fryers. The Board found, and the Federal Circuit agreed, that the disadvantages of pursuing the challenger’s proposed modification of the prior art weighed against obviousness, in the absence of some articulated rationale as to why a person of ordinary skill in the art would have pursued that modification. In addition, the Federal Circuit reiterated that as a matter of procedure, the scope of an inter partes review is limited to the theories of unpatentability presented in the original petition.

Details

Fries are among the most common deep-fried foods, and McDonald’s fries may still be the most popular and highest-consumed worldwide. But, there would be no McDonald’s fries without a deep fryer and a good pot of oil, and Frymaster LLC (“Frymaster”) is the maker of some of McDonald’s deep fryers.

During deep frying, chemical and thermal interactions between the hot frying oil and the submerged food cause the food to cook. These interactions degrade the quality of the oil. In particular, chemical reactions during frying generate new compounds, including total polar materials (TPM), that can change the oil’s physical properties and electrical conductivity.

Frymaster’s fryers are equipped with integrated oil quality sensors (OQS), which monitor oil quality by measuring the oil’s electrical conductivity as an indicator of the TPM levels in the oil. This sensor technology is embodied in Frymaster’s U.S. Patent No. 8,497,691 (“691 patent”).

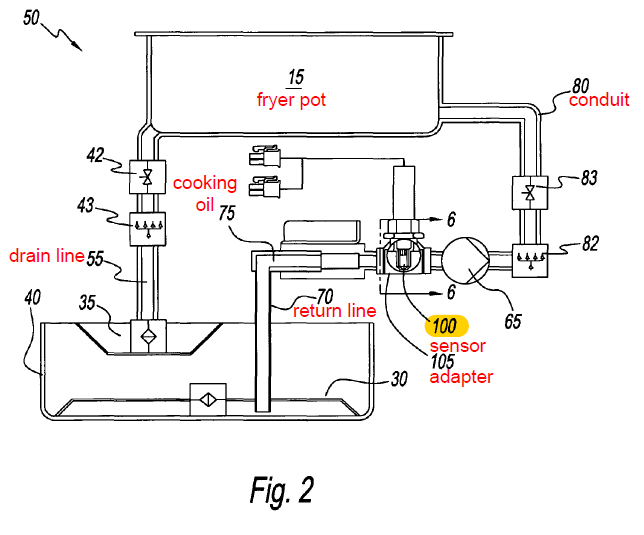

The 691 patent describes an oil quality sensor that is integrated directly into the circulation of cooking oil in a deep fryer, and is capable of taking measurements at the deep fryer’s operational temperatures of 150-180°C, i.e., without cooling the hot oil.

Claim 1 of the 691 patent is representative:

1. A system for measuring the state of degradation of cooking oils or fats in a deep fryer comprising:

at least one fryer pot;

a conduit fluidly connected to said at least one fryer pot for transporting cooking oil from said at least one fryer pot and returning the cooking oil back to said at least one fryer pot;

a means for re-circulating said cooking oil to and from said fryer pot; and

a sensor external to said at least on[e] fryer pot and disposed in fluid communication with said conduit to measure an electrical property that is indicative of total polar materials of said cooking oil as the cooking oil flows past said sensor and is returned to said at least one fryer pot;

wherein said conduit comprises a drain pipe that transports oil from said at least one fryer pot and a return pipe that returns oil to said at least one fryer pot,

wherein said return pipe or said drain pipe comprises two portions and said sensor is disposed in an adapter installed between said two portions, and

wherein said adapter has two opposite ends wherein one of said two ends is connected to one of said two portions and the other of said two ends is connected to the other of said two portions.

Figure 2 of the 691 patent illustrates the structure of Frymaster’s system:

Henny Penny Corporation (HPC) is a competitor of Frymaster, and initiated an inter partes review of the 691 patent.

In its petition, HPC challenged claim 1 of the 691 patent as being obvious over Kauffman (U.S. Patent No. 5,071,527) in view of Iwaguchi (JP2005-55198).

Kauffman taught a system for “complete analysis of used oils, lubricants, and fluids”. The system included an integrated electrode positioned between drain and return lines connected to a fluid reservoir. The electrode measured conductivity and current to monitor antioxidant depletion, oxidation initiator buildup, product buildup, and/or liquid contamination. Kauffman’s system operated at 20-400°C. However, Kauffman did not teach monitoring TPMs.

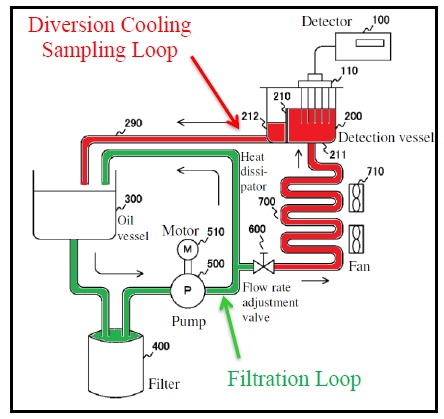

Iwaguchi taught monitoring TPMs to gauge quality of oil in deep fryers. However, Iwaguchi cooled the oil to 40-80°C before taking measurements. If the oil temperature was outside the disclosed range, Iwaguchi’s system would register an error. Specifically, oil was diverted from the frying pot to a heat dissipator where the oil was cooled to the appropriate temperature, and then to a detection vessel where a TPM detector measured the electrical properties of the oil to detect TPMs. Iwaguchi taught that cooling relieved heat stress on the detector, prevented degradation, and obviated the need for large conversion tables.

The parties’ dispute focused on the sensor feature of the 691 patent.

In the initial petition, HPC argued simply that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have found it obvious to modify Kauffman’s system to “include the processor and/or sensor as taught by Iwaguchi.”

In its patent owner’s response, Frymaster disputed HPC’s proposed modification. Frymaster argued that Iwaguchi’s “temperature sensitive” detector would be inoperable in an “integrated” system such as that taught in Kauffman, unless Kauffman’s system was further modified to add an oil diversion and cooling loop. However, such an addition would have been complex, inefficient, and undesirable to those skilled in the art.

In its reply, HPC changed course and argued that it was unnecessary to swap the electrode in Kauffman’s system for Iwaguchi’s detector. HPC argued that Kauffman’s electrode was capable of monitoring TPMs by measuring conductivity, and that Iwaguchi was relevant only for teaching the general desirability of using TPMs to assess oil quality.

However, whereas HPC’s theory of obviousness in its original petition was based on a modification of the physical structure of Kauffman’s system, HPC’s reply proposed changing only the oil quality parameter being measured. During the oral hearing before the Board, HPC’s counsel even admitted to this shift in HPC’s theory of obviousness.

In its final written decision, the Board determined, as a threshold matter of procedure, that HPC impermissibly presented a new theory of obviousness in its reply, and that the patentability of the 691 patent would be assessed only against the grounds asserted in HPC’s original petition.

The Board’s final written decision thus addressed only whether the person skilled in the art would have been motivated to “include”—that is, integrate—Iwaguchi’s detector into Kauffman’s system. The Board found no such motivation.

The Board’s reasoning largely mirrored Frymaster’s arguments. Kauffman’s system did not include a cooling mechanism that would have allowed Iwaguchi’s temperature-sensitive detector to work. Integrating Iwaguchi’s detector into Kauffman’s system would therefore necessitate the addition of the cooling mechanism. The Board agreed that the disadvantages of such additional construction outweighed the “uncertain benefits” of TPM measurements over the other indicia of oil quality already being monitored in Kauffman.

On appeal, HPC raised two issues: first, the Board construed the scope of HPC’s original petition overly narrowly; and second, the Board erred in its conclusion of nonobviousness.[1]

The Federal Circuit sided with the Board on both issues.

On the first issue, the Federal Circuit did a straightforward comparison of HPC’s petition and reply. In the petition, HPC proposed a physical substitution of Iwaguchi’s detector for Kauffman’s electrode. In the reply, HPC proposed using conductivity measured by Kauffman’s electrode as a basis for calculating TPMs. The apparent differences between the two theories of obviousness, together with the “telling” confirmation of HPC’s counsel during oral hearing that the original petition espoused a physical modification, made it easy for the Federal Circuit to agree with the Board’s decision to disregard HPC’s alternative theory raised in its reply.

The Federal Circuit reiterated the importance of a complete petition:

It is of the utmost importance that petitioners in the IPR proceedings adhere to the requirement that the initial petition identify ‘with particularity’ the ‘evidence that supports the grounds for the challenge to each claim.

On the second issue of obviousness, HPC argued that the Board placed undue weight on the disadvantages of incorporating Iwaguchi’s TPM detector into Kauffman’s system.

Here, the Federal Circuit reiterated “the longstanding principle that the prior art must be considered for all its teachings, not selectively.” While “[t]he fact that the motivating benefit comes at the expense of another benefit…should not nullify its use as a basis to modify the disclosure of one reference with the teachings of another”, “the benefits, both lost and gained, should be weighed against one another.”

The Federal Circuit adopted the Board’s findings on the undesirability of HPC’s proposed modification of Kauffman, agreeing that the “tradeoffs [would] yield an unappetizing combination, especially because Kauffman already teaches a sensor that measures other indicia of oil quality.”

At first glance, the nonobviousness analysis in this decision seems to involve weighing the disadvantages and advantages of the proposed modification. However, looking at the history of this case, I think the problem with HPC’s arguments was more fundamentally that they never identified a satisfactory motivation to make the proposed modification. HPC’s original petition argued that the motivation for integrating Iwaguchi’s detector into Kauffman’s system was to “accurately” determine oil quality. This “accuracy” argument failed because it was questionable whether Iwaguchi’s detector would even work at the operating temperature of a deep fryer. Further, HPC did not argue that the proposed modification was a simple substitution of one known sensor for another with the predictable result of measuring TPMs. And when Kauffman argued that the substitution was far from simple, HPC failed to counter with adequate reasons why the person skilled in the art would have pursued the complex modification.

Takeaway

- The petition for a post grant review defines the scope of the proceeding. Avoid being overly generic in a petition for post grant review. It may not be possible to fill in the details later.

- Context matters. If an Examiner is selectively citing to isolated disclosures in a prior art out of context, consider whether the context of the prior art would lead away from the claimed invention.

- The MPEP is clear that the disadvantages of a proposed combination of the prior art do not necessarily negate the motivation to combine (see, e.g., MPEP 2143(V)). The disadvantages should preferably nullify the Examiner’s reasons for the modification.

[1] On the issue of obviousness, HPC also objected to the Board’s analysis of Frymaster’s proffered evidence of industry praise as secondary considerations. This objection is not addressed here.

Standing to Appeal an Adverse IPR Decision to the CAFC

| August 16, 2018

JTEKT Corp. v. GKN Automotive Ltd.

August 3, 2018

Before Prost, Dyk and O’Malley. Opinion by Dyk.

Summary:

JTEKT Corporation (“JTEKT”) instituted an inter partes review (“IPR”) of the patentability of claims 1-7 of U.S. Patent No. 8,215,440 (“the ‘440 patent”), owned by GKN Automotive (“GKN”). The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“the Board”) issued an adverse decision regarding claims 2 and 3, holding that JTEKT did not show that claims 2 and 3 would have been obvious over the prior art of Teraoka in view of Watanabe. JTEKT appealed the adverse decision to the CAFC. The CAFC dismissed the appeal, finding that JTEKT lacks standing to appeal.

A “Teaching Away” Argument Must be Commensurate in Scope with the Claims

| October 17, 2017

Idemitsu Kosan Co., Ltd. v. SFC Co. Ltd.

September 15, 2017

Before Prost, O’Malley and Chen. Opinion by O’Malley.

Summary:

This case is an appeal from an inter partes review of Idemitsu Kosan Co., Ltd’s (“Idemitsu”) U.S. Patent No. 8,334,648 (“the ‘648 patent”) brought by SFC Co. Ltd. (“SFC”). Idemitsu argued on appeal that the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) did not explain why a skilled artisan would have been led to use the claimed combination of compounds from the teachings of the prior art reference Arakane given that Arakane limits its combination of compounds to combinations satisfying a special relationship. The CAFC agreed with the PTAB in holding that the Arakane reference teaches compounds (including the claimed compounds among others) that when combined, produce a light emitting layer, regardless of the special relationship. The CAFC further held that “evidence concerning whether the prior art teaches away from a given invention must relate to and be commensurate in scope with the ultimate claims at issue.” In this case, the CAFC said that it is not particularly important that Arakane teaches that combinations of compounds not satisfying the special relationship result in poor performance because the claims at issue do not include limitations with respect to performance.

Details:

Idemitsu’s ‘648 patent is to an “Organic Electroluminescence Device and Organic Light Emitting Medium.” Claim 1 is provided below:

1. An electroluminescence device comprising a pair of electrodes and a layer of an organic light emitting medium disposed between the pair of electrodes, wherein the layer of an organic light emitting medium is present as a light emitting layer and comprises:

(A) an arylamine compound represented by formula V:

wherein X3 is a substituted or unsubstituted pyrene residue,

Ar5 and Ar6 each independently represent a substituted or unsubstituted monovalent aromatic group having 6 to 40 carbon atoms, and

p represents an integer of 1 to 4; and

(B) at least one compound selected from the group consisting of anthracene derivatives and spirofluorene derivatives, wherein

said anthracene derivatives are represented by formula I:

wherein A1 and A2 may be the same or different and each independently represent a substituted or unsubstituted monophenylanthryl group or a substituted or unsubstituted diphenylanthryl group, and L represents a single bond or a divalent bonding group, and by formula II:

wherein An represents a substituted or unsubstituted divalent anthracene residue, A3 and A4 may be the same or different and each independently represent a substituted or unsubstituted aryl group having 6 to 40 carbon atoms, at least one of A3 and A4 represents a substituted or unsubstituted monovalent condensed aromatic ring group or a substituted or unsubstituted aryl group having 10 or more carbon atoms; and

said spirofluorene derivatives are represented by formula III:

wherein Ar1 represents a substituted or unsubstituted spirofluorene residue, A5 to A8 each independently represent a substituted or unsubstituted aryl group having 6 to 40 carbon atoms;

provided that the organic light emitting medium does not include a styryl aryl compound.

SFC petitioned for an inter partes review (IPR) of the ‘648 patent. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) instituted review of the claims on the grounds of obviousness based on a single reference to Arakane (WO 02/052904). The Arakane reference is assigned to Idemitsu and teaches an organic electroluminescence device. Arakane discloses:

The present invention provides an organic electroluminescence device including a pair of electrodes and an organic light emitting medium layer interposed between the electrodes wherein the organic light emitting medium layer has a mixture layer containing (A) at least one hole transporting [“HT”] compound and (B) at least one electron transporting [“ET”] compound and the energy gap Eg1 of the [HT] compound and the energy gap Eg2 of the [ET] compound satisfy the relation Eg1<Eg2.

Among the HT compounds, Arakane discloses a compound corresponding to formula V of claim 1. And among ET compounds, Arakane discloses compounds corresponding to compounds of formulas I and II of claim 1, respectively.

The PTAB held the claims of the ‘648 patent to be obvious over Arakane. Specifically, the PTAB held that Arakane’s HT compound corresponds with the formula V compound of claim 1; that Arakane’s ET compounds correspond with compounds of formulas (I) and (II) of claim 1; and that Arakane teaches that a light emitting layer can be formed by combining an HT and ET compound. The PTAB stated that the claimed invention “is the combination of recited components in a light emitting layer” and that “Arakane’s disclosure would have informed an ordinary artisan that combining components (A) and (B) would produce a light emitting layer.” The PTAB further stated that the obviousness of the combination “does not depend on whether the resulting light emitting layer would satisfy Arakane’s energy gap relationship.”

Idemitsu argued on appeal that the PTAB made no finding with respect to the energy gap relationship taught in Arakane, i.e., that the energy gap of the HT compound must be less than the energy gap of the ET compound. The CAFC stated that the PTAB correctly found that Arakane suggests combinations of HT and ET compounds that produce a light emitting layer, regardless of their energy gap relation.

Idemitsu also argued that this was raised too late because it was not in SFC’s petition or in the PTAB’s institution decision. However, the CAFC stated that Idemitsu is the party that implicitly raised the argument by arguing that SFC failed to explain why a skilled artisan would have been led to use the combination of HT and ET compounds given that Arakane limits the combination of compounds to combinations satisfying the energy gap relationship. In its counterargument, SFC argued that Arakane does not teach away from the claimed combination despite the absence of demonstrating that the combination would possess the preferred energy gap relationship. The CAFC stated that SFC’s statements were “the by-product of one party necessarily getting the last word,” and thus the argument was not raised too late.

The CAFC also noted that Idemitsu provided no supporting evidence for its position that Arakane teaches away from non-energy gap HT/ET combinations, and that SFC was not required to rebut attorney argument with expert testimony.

The CAFC further stated that Idemitsu’s argument regarding “teaching away” is of questionable relevance. The CAFC explained that “evidence concerning whether the prior art teaches away from a given invention must relate to and be commensurate in scope with the ultimate claims at issue.” The CAFC also included the following passage from In re Zhang, 654 F. App’x 490 (Fed. Cir. 2016): “While a prior art reference may indicate that a particular combination is undesirable for its own purposes, the reference can nevertheless teach that combination if it remains suitable for the claimed invention.” The claims at issue do not include limitations with respect to performance characteristics. And Arakane teaches that the only drawback of not satisfying the energy gap relationship is poor performance. Thus, the CAFC concluded that it is of substantially reduced importance that the non-energy-gap HT/ET combinations result in poor performance.

Take Away

As a patent applicant or patent owner, when arguing that a reference teaches away from a claimed invention to demonstrate non-obviousness, you should try to explain why the reference teaches unsuitability of the claimed invention. Relying solely on a teaching of undesirability in the prior art may not be enough to demonstrate a teaching away from the claimed invention.

This case also emphasizes the importance of supporting arguments with expert declarations in inter partes reviews. Idemitsu did not provide evidence supporting a teaching away argument. Thus, SFC and the PTAB could rely solely on the text of the reference.

A Patent Owner in an IPR is entitled to an opportunity to respond to asserted facts

| December 16, 2016

In Re: NuVasive, Inc.

November 9, 2016

Before Moore, Wallach and Taranto. Opinion by Taranto.

Summary:

Medtronic filed two petitions for inter partes review (IPR) against U.S. Patent 8,187,334 to a spinal fusion implant owned by NuVasive. The claims of the ‘334 patent recite two size requirements: that the length of the implant is greater than 40 mm and that the length to width ratio is 2.5. In both petitions, Medtronic cited the combination of two references for teaching the size limitations. In the patent owner responses, NuVasive addressed the combination of references as in Medtronic’s petition. However, in Medtronic’s reply, Medtronic changed its reliance to just one of the cited references for teaching both of the size limitations citing a different portion of the reference. The PTAB ultimately relied on Medtronic’s changed position in its final decision. In one IPR, the CAFC held that NuVasive had an opportunity to respond because Medtronic’s petition was at least minimally sufficient to provide notice. However, in the second IPR, NuVasive was not given proper notice to respond.

Next Page »