File your patent application before attending a trade show to showcase your products

| May 26, 2023

Minerva Surgical, Inc. v. Hologic, Inc., Cytyc Surgical Products, LLC

Decided: February 15, 2023

Summary:

Minerva Surgical, Inc. sued Hologic, Inc. and Cytyc Surgical Products, LLC in the District of Delaware for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 9,186,208 (“the ’208 patent”). Hologic moved for summary judgment of invalidity, arguing that the ’208 patent claims were anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b). The district court granted summary judgment that the asserted claims are anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) because the patented technology was “in public use,” and the technology was “ready for patenting.” The Federal Circuit held that the district court correctly determined that Minerva’s disclosure of their constituted the invention being “in public use,” and that the device was “ready for patenting.” Therefore, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s grant of summary judgment.

Details:

Minerva Surgical, Inc. sued Hologic, Inc. and Cytyc Surgical Products, LLC in the District of Delaware for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 9,186,208 (“the ’208 patent”).

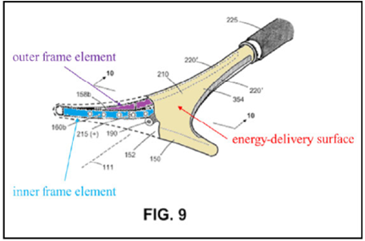

The ’208 patent is directed to surgical devices for a procedure called “endometrial ablation” for stopping or reducing abnormal uterine bleeding. This procedure includes inserting a device having an energy-delivery surface into a patient’s uterus, expanding the surface, energizing the surface to “ablate” or destroy the endometrial lining of the patient’s uterus, and removing the surface.

The application for the’208 patent was filed on November 2, 2021 and claims a priority date of November 7, 2011. Therefore, the critical date for the ’208 patent is November 7, 2010.

The ’208 patent

Independent claim 13 is a representative claim:

A system for endometrial ablation comprising:

an elongated shaft with a working end having an axis and comprising a compliant energy-delivery surface actuatable by an interior expandable-contractable frame;

the surface expandable to a selected planar triangular shape configured for deployment to engage the walls of a patient’s uterine cavity;

wherein the frame has flexible outer elements in lateral contact with the compliant surface and flexible inner elements not in said lateral contact, wherein the inner and outer elements have substantially dissimilar material properties.

The appeal focused on the claim term, “the inner and outer elements have substantially dissimilar material properties” (“SDMP” term”).

District Court

After discovery, Hologic moved for summary judgment of invalidity, arguing that the ’208 patent claims were anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b).

The district court granted summary judgment that the asserted claims are anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) because of the following reasons:

First, the patented technology was “in public use” because Minerva disclosed fifteen devices (“Aurora”) at an event, where Minerva showcased them at a booth, in meeting with interested parties, and in a technical presentation. Also, Minerva did not disclose them under any confidentiality obligations.

Second, the technology was “ready for patenting” because Minerva created working prototypes and enabling technical documents.

Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit reviewed a district court’s grant of summary judgment under the law of the regional circuit (Third Circuit).

The Federal Circuit held that “the public use bar is triggered ‘where, before the critical date, the invention is [(1)] in public use and [(2)] ready for patenting.’”

The “in public use” element is satisfied if the invention “was accessible to the public or was commercially exploited” by the invention.

“Ready for patenting” requirement can be shown in two ways – “by proof of reduction to practice before the critical date” and “by proof that prior to the critical date the inventor had prepared drawings or other descriptions of the invention that were sufficiently specific to enable a person skilled in the art to practice the invention.”

The Federal Circuit held that disclosing the Aurora device at the event (American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (“AAGL 2009”)) constituted the invention being “in public use” because this event included attendees who were critical to Minerva’s business, and Minerva’s disclosure of their devices included showcasing them at a booth, in meeting with interested parties, and in a technical presentation.

The Federal Circuit noted that AAGL 2009 was the “Super Bowl” of the industry and was open to the public, and that Minerva had incentives to showcase their products to the attendees. Also, Minerva sponsored a presentation by one of their board members to highlight their products and pitched their products to industry members, who were able to see how they operate.

The Federal Circuit also noted that there were no “confidentiality obligations imposed upon” those who observed Minerva’s devices, and that the attendees were not required to sign non-disclosure agreements.

The Federal Circuit also held that Minerva’s Aurora devices at the event disclosed the SDMP term because Minerva’s documentation about this device from before and shortly after the event disclosed this device having the SDMP terms or praises benefits derived from this device having the SDMP technology.

The Federal Circuit held that the record clearly showed that Minerva reduced the invention to practice by creating working prototypes that embodied the claim and worked for the intended purpose.

The Federal Circuit noted that there was documentation “sufficiently specific to enable a person skilled in the art to practice the invention” of the disputed SDMP term. Here, the documentation included the drawings and detailed descriptions in the lab notebook pages disclosing a device with the SDMP term.

Therefore, the Federal Circuit held that the district court correctly determined that Minerva’s disclosure of the Aurora device constituted the invention being “in public use” and that the device was “ready for patenting.”

Accordingly, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s grant of summary judgment because there are no genuine factual disputes, and Hologic is entitled to judgment as a matter of law that the ’208 patent is anticipated under the public use bar of § 102(b).

Takeaway:

- File your patent application before attending a trade show to showcase your products.

- Have the attendees of the trade show sign non-disclosure agreements, if necessary.

Tags: 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) > confidentiality > critical date > enablement > pre-AIA > prototype > public use > reduction to practice > summary judgment

Environment of confidentiality and tight control trumps publicly visible location of invention in “public use” challenge to patent validity

| January 27, 2015

Delano Farms Company v. California Table Grape Comm.

January 9, 2015

Panel: Prost, Bryson, and Hughes. Opinion by Bryson.

Summary

In a case involving plant patents, the CAFC expounds on what constitutes, and does not constitute, a public use. The touchstone of public use is “whether the purported use was accessible to the public or was commercially exploited.” A formal confidentiality agreement is not required to show non-public use. Because there was an environment of confidentiality and tight control in the actions of the third parties who obtained unauthorized possession of the plant material prior to the critical date, and their use was not accessible to the public, there was no invalidating public use.

Details

After disposing of various procedural issues, the CAFC addressed a challenge to the validity of two plant patents under 35 USC § 102(b) (pre-AIA) based on an alleged public use more than one year before the applications for the patents were filed.

Following a bench trial, the district court found that the actions of two individuals who obtained samples of the two patented plant varieties in an unauthorized manner and planted them in their own fields did not constitute a public use of the two plant varieties and therefore rejected the plaintiffs’ challenge to the patents. The CAFC affirmed.

The patent applications were filed on September 28, 2004, making the critical date for a section 102(b) public use bar September 28, 2003. Both plant varieties were made commercially available on July 13, 2005, well after both the critical and filing dates. In 2001, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (“USDA”) held an experimental variety open house, which was attended by cousins Jim and Larry Ludy. Jim Ludy asked a USDA employee for some of the plant material for the two varieties. Although the plant material was not commercially released, and the USDA employee was not authorized to do so, he complied with the request, on the condition that the Ludys not sell the resulting grapes until the varieties were commercially released. Jim Ludy understood that he was to keep the plant material secret, and he understood the adverse consequences if he failed to do so.

Jim Ludy subsequently grew a number of plants from the plant material, and provided a few buds to Larry. Larry was aware of the origins of the plant material, and admitted that Jim told him they should keep it to themselves. Larry grew more plants from the buds he got from Larry, and showed them to his marketer at least twice before the critical date. The Ludys sold no grapes from their plantings before the critical date. After the critical date, the marketer sold grapes harvested from the vines under the name of an unrelated variety to avoid detection. Also after the critical date, Larry Ludy provided some of the plant material to the marketer, who recognized the competitive advantage in possessing plants that were not commercially released.

Based on these findings, the district court found that the plaintiffs failed to meet their burden of showing, by clear and convincing evidence, that the Ludys’ use of the unreleased varieties constituted an invalidating public use.

The CAFC begins its legal analysis by stating the test for public use as being “whether the purported use was accessible to the public or was commercially exploited.” To be accessible to the public, the actions that constitute the use must “create a reasonable belief as to the invention’s public availability.” Regardless of whether the actions are taken by the inventor or an unaffiliated third party, relevant factors include:

- “the nature of the activity that occurred in public”

- “the public access to and knowledge of the public use”

- “whether there was any confidentiality obligation imposed on persons who observed them” and if so, the degree of confidentiality

- [t]he adequacy of any confidentiality guarantees … measured in relation ‘to the party in control of the allegedly invalidating prior use’”

“[A]n agreement of confidentiality, or circumstances creating a similar expectation of secrecy, may negate a public use where there is not commercial exploitation.” Analogously, a secret or confidential third-party use is not an invalidating public use.

In this case, Jim obtained the plant material with the expectation of secrecy and impressed the need for secrecy on Larry; and even after the critical date, they both acted to conceal their possession of the plants. The facts are thus readily distinguishable from the seminal Supreme Court decision in Egbert v. Lippmann, 104 U.S. 333 (1881), in which the inventor of a corset gave two of them to a friend to use, without limitation, restriction, or injunction of secrecy.

The CAFC also pointed out that a formal confidentiality agreement is not required to prove that a use is not public.

With respect to disclosure to the marketer, the CAFC referred to the district court’s finding that there was an environment of confidentiality and tight control, and thus no public use.

Finally, the CAFC considered the impact of Ludys growing the plants in locations that were visible from public roads. The public nature of the location was counteracted by the facts that grape varieties cannot be reliably identified simply by viewing the growing vines, the plantings in question were extremely limited in comparison to the total cultivation of their farms, the plantings were not labeled in any way, and there was no evidence that anyone other than the Ludys and their marketer recognized them.

The CAFC concluded based on the district court’s finding of fact that the purported use was not accessible to the public and did not put the public in possession of the patented plants.

Takeaway

A use by an inventor or an unaffiliated third party is not necessarily a public use, even if the use is made without an explicit confidentiality agreement. Even without a confidentiality agreement an environment of confidentiality and tight control over the invention and its use can prevent the use from being construed as an invalidating public use.

Tags: commercial exploitation > confidential use > confidentiality > control > public access > public availability > public use > secret use