Claim Construction Should Be Well-Grounded in Both Intrinsic and Extrinsic Evidence

| January 15, 2024

ACTELION PHARMACEUTICALS LTD v. MYLAN PHARMACEUTICALS INC.

Decided: November 6, 2023

Before REYNA, STOLL, and STARK, Circuit Judges.

Summary

The Federal Circuit ruled that the patent claim term “a pH of 13 or higher” could not be interpreted solely based on the patent’s intrinsic evidence. The court remanded the case to the district court, instructing it to consider extrinsic evidence to determine the proper construction of this claim limitation.

Background

The case of Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd v. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. involves a dispute over patent infringement related to epoprostenol, a drug used for treating hypertension. Actelion Pharmaceuticals, the patent holder, owns two patents of the drug: U.S. Patent Nos. 8318802 and 8598227. These patents disclose a pharmaceutical breakthrough in stabilizing epoprostenol using a high pH solution, which is otherwise unstable and difficult to handle in medical applications.

Mylan Pharmaceuticals, aiming to enter the market with a generic version of epoprostenol, filed an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). In this process, Mylan certified under Paragraph IV that the patents held by Actelion were either invalid or would not be infringed by Mylan’s manufacture, use, or sale of the generic drug. In response, Actelion asserted these patents against Mylan, claiming infringement.

The key issue in the dispute revolves around the interpretation of the phrase “a pH of 13 or higher” in the patent claims. This particular claim is crucial because the stability of epoprostenol is significantly impacted by the pH level of its solution. Actelion’s patents suggest that the epoprostenol bulk solutions should preferably have a pH adjusted to about 12.5 to 13.5 to achieve the desired stability. However, in the claims, Actelion’s patents only set the limitation as “a pH 13 or higher” as shown in claim 11 of the ’802 patent, a representative of the asserted claims:

11. A lyophilisate formed from a bulk solution comprising:

(a) epoprostenol or a salt thereof;

(b) arginine;

(c) sodium hydroxide; and

(d) water,

wherein the bulk solution has a pH of 13 or higher, and wherein said lyophilisate is capable of being reconstituted for intravenous administration with an intravenous fluid.

The dispute centered on the interpretation of the pH value specified in the patent claims. Actelion contended that the claim should encompass pH values that effectively round up to 13, including values like 12.5. Conversely, Mylan argued for a narrower interpretation, asserting that the claim should only cover pH values strictly at 13 or higher, thus excluding anything below this threshold, such as 12.5.

This interpretation was critical in determining whether Mylan’s generic version of epoprostenol would infringe upon Actelion’s patents. The district court initially adopted Actelion’s interpretation, which led to a stipulated judgment of infringement against Mylan.

Discussion

The Federal Circuit’s analysis began with a de novo review of the district court’s decision. The central question was whether the district court’s adoption of Actelion’s interpretation, which included pH values that could round up to 13 (such as 12.5), was appropriate. This broader interpretation affected the scope of the patent and the potential infringement by Mylan’s generic version of the drug. In scientific and technical contexts, the practice of rounding pH levels, such as rounding 12.5 to 13, depends on the specific requirements of the situation and the level of precision needed. pH is a logarithmic scale used to specify the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution, and even small changes can represent significant differences in acidity or basicity.

Mylan Pharmaceuticals argued for a narrower interpretation of the term. They insisted that “a pH of 13” sets a definitive lower limit, suggesting that any pH value below 13, even those marginally lower like 12.995, would not fall within the scope of the patent. Mylan suggested that if a margin of error was considered necessary for a pH of 13, it should be minimal, encompassing a range only from 12.995 to 13.004. This interpretation was grounded in the belief that precision was implicit in the claim term, as the absence of approximation language like “about” in the claim suggested an exact value.

In contrast, Actelion Pharmaceuticals argued for a broader interpretation. They argued that the term should include values that round up to 13, thus potentially including values such as 12.5. Actelion’s argument was based on the principle that a numerical value in a patent claim includes rounding, dictated by the inventor’s selection of significant figures, unless the intrinsic record explicitly indicates a different intention. Actelion maintained that rounding was a common practice in scientific measurements and that the absence of specific approximation language did not necessarily dictate a precise value.

One of the key findings of the Federal Circuit was the inadequacy of intrinsic evidence to resolve the dispute conclusively. Intrinsic evidence, which includes the original patent claim language, specification, and prosecution history, is generally the primary resource for interpreting patent claims. However, in this case, these sources did not clearly define the precision of the pH value in question. The specification stated that, “the pH of the bulk solution is preferably adjusted to about 12.5-13.5, most preferably 13.” This language suggested that while the inventor recognized a preferred range (about 12.5-13.5), they specifically highlighted a most preferred value (13). The Federal Circuit also noted that the specification uses both “13” and “13.0” and various degrees of precision for pH values generally throughout the specification. Moreover, the prosecution history shows that the Examiner drew a distinction between the stability of a composition with a pH of 13 and that of 12. However, such distinction does not clarify the narrower issue of whether a pH of 13 could encompass values that round to 13, in particular 12.5.

The specifications and prosecution history left ambiguous whether the term referred exclusively to a pH of 13.0 or could include values that round up to 13. Recognizing this ambiguity, the Federal Circuit emphasized the need for extrinsic evidence to properly interpret the term. This approach is aligned with the Supreme Court’s guidance in Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. v. Sandoz, Inc., which acknowledged the importance of considering such evidence in certain contexts of patent claim interpretation. The Federal Circuit decided to vacate the district court’s ruling and remand the case for further consideration of extrinsic evidence.

Takeaway

- Precise and specific wording in patent claims is crucial, especially in technical fields, as it defines the scope and protection of the invention.

- Although intrinsic evidence (claim language, specifications, and prosecution history) is primary in patent interpretation, it may not always be sufficient. In cases where intrinsic evidence is ambiguous or lacks clarity, extrinsic evidence such as expert testimonies, scientific literature, and other technical documents becomes crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the claim.

IPR Amendments: Broader is Broader (even narrowly so).

| September 15, 2023

Sisvel International S.A. v. Sierra Wireless, Inc, Telit Cinterion Deuschland GMBH

Decided: September 1, 2023

Before Prost, Reyna and Stark. Authored by Stark.

Summary: Sisvel appealed a PTAB IPR decision based on claim construction and denial of entry of a claim amendment for broadening the claim. The CAFC affirmed the Board on both counts, noting that broad disclosures in the specification will lead to a broad interpretation of the claims, and that claim amendments which encompass embodiments that would come within the scope of the amended claim but would not have infringed the original claim will be considered broadening.

Background:

In an IPR involving Sisvel’s patent claims 10, 11, 13, 17, and 24 of U.S. Patent No. 7,433,698 (the “’698 patent”) and claims 1, 2, 4, and 13-18 of U.S. Patent No. 8,364,196 (the “’196 patent”), the PTAB had found all claims unpatentable as anticipated and/or obvious in view of certain prior art.

The issues centered on the phraseology in the claims regarding the “connection rejection message” being used to direct a mobile communication means to attempt a new connection with certain parameter values such as a certain carrier frequency.

Claim 10, reproduced below, was the primary representative claim used by the CAFC:

10. A channel reselection method in a mobile communication means of a cellular telecommunication system, the method comprising the steps of:

receiving a connection rejection message;

observing at least one parameter of said connection rejection message; and

setting a value of at least one parameter for a new connection setup attempt based at least in part on information in at least one frequency parameter of said connection rejection message.

On appeal, Sisvel challenged the Board’s construction of the single claim term, “connection rejection message.”

Sisvel also challenged the Board’s denial of their motion to amend the claims on the basis that the amendment enlarged their scope.

Decision:

(a) Claim construction of “connection rejection message”

Sisvel appealed the Board’s construction of giving “connection rejection message” its plain and ordinary meaning of “a message that rejects a connection.” Sisvel’s purported a construction of “a message from a GSM or UMTS telecommunications network rejecting a connection request from a mobile station.” However, the PTAB found that such a construction would improperly limit the claims to embodiments using a Global System for Mobile Communication (“GSM”) or Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (“UMTS”) network.

Sisvel argued that UMTS and GSM “are the only specific networks identified by [the] ’698 and ’196 patents that actually send connection rejection messages” provided for in their specification.

The CAFC, in required fashion, reiterated the Phillips claim-construction standard – whereby “[t]he words of a claim are generally given their ordinary and customary meaning as understood by a person of ordinary skill in the art when read in the context of the specification and prosecution history,” citing Thorner v. Sony Comput. Ent. Am. LLC, 669 F.3d 1362, 1365 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (citing Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303, 1313 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (en banc)) 669 F.3d at 1365.

After reviewing, the Court found that the intrinsic evidence provided no persuasive basis to limit the claims to any particular cellular networks. They noted that the specification, while only expressly disclosing embodiments in a UMTS or GSM network, in fact still included broad teachings directed to any network. The CAFC affirmed the Board, noting that a person of ordinary skill in the art would not read the broad claim language, accompanied by the broad specification statement to be limited to GSM and UMTS networks.

(b) IPR Amendment

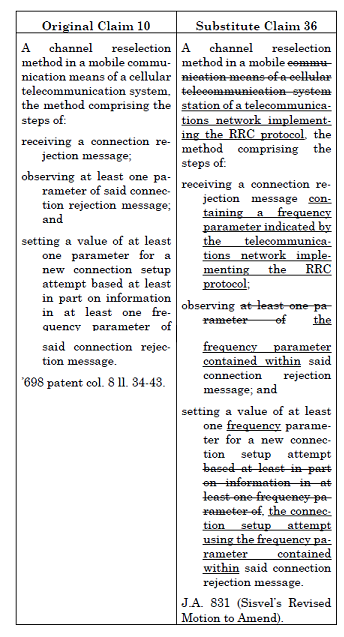

The Court also considered Sisvel’s contention that the Board erred during the IPR by denying its motion to amend the claims of the ’698 patent. The Board had denied Sisvel’s motion, concluding that the amendments to original claim 10 would have impermissibly enlarged claim scope. Original claim 10 and substitute amended claim 36 read as follows:

The Court first noted that broadening claims are not allowable during an IPR in the same fashion as in a Reissue or Reexamination proceeding at the USPTO. They further delved into the law of what constitutes a broadening of a claim noting that a claim “is broader in scope than the original claim if it contains within its scope any conceivable apparatus or process which would not have infringed the original patent” citing Hockerson-Halberstadt, Inc. v. Converse Inc., 183 F.3d 1369, 74 (Fed. Cir. 1999).

The Court further remarked that it is Sisvel’s burden, as the patent owner, to show that the proposed amendment complies with relevant regulatory and statutory requirements, citing to 37 C.F.R. § 42.121(d)(1) (“A patent owner bears the burden of persuasion to show, by a preponderance of the evidence, that the motion to amend complies with the [applicable] requirements . . . .”).

The PTAB’s denial had focused on the last (“setting a value”) limitation, comparing the original claim’s requirement that the value be set “based at least in part on information in at least one frequency parameter” of the connection rejection message, while in the substitute claims the value may be set merely by “using the frequency parameter” contained within the connection rejection message. The Board had concluded that “[i]n proposed substitute claim 36, the value that is set need not be based, in whole or in part, on information in the connection rejection message and, thus, claim 36 is broader in this respect than claim 10.” J.A. 73.

The Court agreed with the PTAB’s reasoning that, in the context of these claims, “using” is broader than “based on” and that whereas the original claim language required that the value in a new connection setup attempt be at least in some respect impacted by (i.e., “based” on) the frequency parameter, the substitute claim removes this requirement. They concluded that this removal of a claim requirement can broaden the resulting amended claim, because it is conceivable there could be embodiments that would come within the scope of substitute claim 36 but would not have infringed original claim 10, citing Pannu v. Storz Instruments, Inc., 258 F.3d 1366, 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2001) (“A reissue claim that does not include a limitation present in the original patent claims is broader in that respect.”).

Take aways:

- The Phillips standard is reiterated with the Court finding that even general disclosures within a specification (i.e. not supported by any embodiments) will provide sufficient intrinsic evidence that a skilled artisan will be considered to interpret the claim language to encompass the general disclosures.

- Drafting claim amendments in a post-grant proceeding at the USPTO must be done with extreme care. Any logically conceivable interpretation of the amendment whereby embodiments would come within the scope of substitute claim but would not have infringed the original claim will be considered broadening.

Claim Construction Should be Well-Grounded in Intrinsic Evidence

| August 3, 2023

MEDYTOX, INC. v. GALDERMA S.A.

Decided: June 27, 2023

Before DYK, REYNA, and STARK, Circuit Judges.

Summary

The CAFC upheld a decision by the PTAB in a post-grant review involving a patent for a botulinum toxin treatment. The patent owner attempted to replace original claims with substitute claims was rejected by the Board, leading to the cancellation of the original claims and the finding that the substitute claims were unpatentable. The court affirmed the Board’s decision, emphasizing the challenges of amending claims in post-grant proceedings.

Background

Medytox owns U.S. Patent No. 10,143,728 (‘728 patent), issued in December 2018, which is directed to a method that uses an animal-protein-free botulinum toxin composition for cosmetic and non-cosmetic applications. Galderma filed a petition for post-grant review (PGR) proceedings at the PTAB to challenge the validity of ‘728 patent claims.

During the PGR proceedings, Medytox attempted to modify all 10 claims of its ‘728 patent and obtained initial feedback on proposed substitute claims under the PTAB’s amendment motion pilot program. The PTAB’s preliminary guidance revealed that Medytox did not meet the statutory requirements for submitting an amendment motion. However, the board acknowledged that the new phrase claiming “a responder rate at 16 weeks after the first treatment of 50% or greater” neither introduced new matter nor suggested a range of responder rates. Despite this, Galderma opposed Medytox’s substitute claims, arguing that the ‘728 patent’s specification only revealed responder rates up to 62% in clinical trials, whereas Medytox’s claim language encompassed a range of responder rates from 50% to 100%.

Contrary to its initial guidance, the PTAB issued a final written decision in the PGR proceedings, ruling that the substitute claims introduced new matter regarding to the responder rate limitation. Medytox asserted that the 50% responder rate was claimed as a minimum threshold and not a range. Nevertheless, the PTAB found the substitute claim language to be invalid for indefiniteness after reviewing the complete record, as “a skilled artisan would not have been able to achieve higher responder rates under the guidance provided in the specification without undue experimentation.” Ultimately, the Board cancelled the original claims 1-5 and 7-10 and also found that the substitute claims to be unpatentable.

Below, substitute claim 19 is provided as a representative of the substitute claims.

19. A method for treating glabellar lines

a conditionin a patient in need thereof, comprising:locally administering a first treatment of

therapeutically effective amount ofa botulinum toxin composition comprising a serotype A botulinum toxin in an amount pre-sent in about 20 units of MT10109L, a first stabilizer comprising a polysorbate, and at least one additional stabilizer, and that does not comprise an animal-derived product or recombinant human albumin;locally administering a second treatment of the botulinum toxin composition at a time interval after the first treatment;

wherein said time interval is the length of effect of the serotype A botulinum toxin composition as determined by physician’s live assessment at maximum frown;

wherein said botulinum toxin composition has a greater length of effect compared to about 20 units of BOTOX®, when

whereby the botulinum toxin composition exhibits a longer lasting effect in the patient when com-pared to treatment of the same condition with a botulinum toxin composition that contains an animal-derived product or recombinant human albumin dosed at a comparable amount andadministered in the same manner for the treatment of glabellar linesand to the same locations(s)as that of the botulinum toxin composition; andwherein said greater length of effect is determined by physician’s live assessment at maximum frown and requires a responder rate at 16 weeks after the first treatment of 50% or greater.

that does not comprise an animal-derived product or recombinant human albumin, wherein the condition is selected from the group consisting of glabellar lines, marionette lines, brow furrows, lateral canthal lines, and any combination thereof.

Discussion

The key issues in the case were the responder rate limitation and whether the substitute claims contained new matter not found in the patent specification. The responder rate limitation referred to the proportion of patients who responded favorably to the treatment with Medytox’s animal-protein-free botulinum toxin composition. In the appeal, Medytox contested the Board’s findings on claim construction, new matter, written description, and enablement, as well as the Board’s Pilot Program on amending practice and procedure under the Administrative Procedure Act.

The Board’s interpretation of the responder rate limitation as a range was the first issue addressed. Medytox argued that the responder rate limitation should be viewed as a binary (“yes-or-no”) inquiry, serving as a “threshold” for determining whether the animal protein-free composition has a more extended effect than BOTOX®.

According to Galderma, Medytox failed to cite intrinsic evidence supporting its suggested claim construction. Galderma also asserts that Medytox did not propose its “minimum threshold” interpretation of the responder rate limitation until after the Preliminary Guidance was released. Medytox did not substantively counter Galderma’s claim but instead insisted that extrinsic evidence supports their claim construction.

The court upheld the Board’s decision and noted that it is typically considered that intrinsic evidence, such as the specification and the prosecution history, is the most crucial consideration in a claim construction analysis. The court cited the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent landmark decision in Amgen v. Sanofi (2023) when nixing Medytox’s challenge to the PTAB’s lack of enablement determination. Under Amgen, “[t]he more one claims, the more one must enable,” and the court noted that data tables included with the ‘728 patent’s specification only disclosed responder rates of 52%, 61% and 62%. While the parties do not substantially dispute the responder rate limitation as a “threshold” or “range,” the Board’s construction of the responder rate limitation as a range in the substitute claims was ultimately affirmed.

Furthermore, the court concluded that the Board’s change in claim construction between its Preliminary Guidance and final written decision was not arbitrary and capricious and did not violate due process or the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). The court emphasized that the Board’s Preliminary Guidance, as indicated in its statement, is “initial, preliminary, [and] non-binding”, and only provides initial views on whether the patent owner has demonstrated a reasonable likelihood of meeting the requirements for filing an amendment motion. The court cited previous rulings which state that the Board must reevaluate matters based on the full record, especially when the standard changes, and that it is encouraged to modify its viewpoint if further development of the record necessitates such a change. Therefore, the Board’s decision to alter its claim construction for the responder rate limitation was not deemed arbitrary and capricious.

Takeaway

- The evolution of the record over the course of a proceeding can significantly impact the outcome, necessitating adjustments in views and decisions as the evidence develops.

- Arguments related to claim construction should be well-grounded in the intrinsic evidence, which includes the specification and the prosecution history, as these are typically the most important considerations in claim construction.

- Claims should be well-grounded in the specification.

A Claim term referring to an antecedent using “said” or “the” cannot be independent from the antecedent

| February 24, 2023

Infernal Technology, LLC v. Activision Blizzard Inc.

Decided: January 24, 2023

Moore, Chen, Stoll. Opinion by Chen.

Summary:

Infernal sued Activision for infringement of its patents to lighting and shadowing methods for use with computer graphics based on nineteen Activision video games. Based on the construction of the claim term “said observer data,” Activision filed a motion for summary judgment of non-infringement. The CAFC agreed with the District Court’s analysis of the noted claim term and affirmed the motion for summary judgment of non-infringement.

Details:

Infernal owns the related U.S. Patent Nos. 6,362,822 and 7,061,488 to “Lighting and Shadowing Methods and Arrangements for Use in Computer Graphic Simulations” providing methods of improving how light and shadow are displayed in computer graphics. Claim 1 of the ‘822 patent is provided:

1. A shadow rendering method for use in a computer system, the method comprising the steps of:

[1(a)] providing observer data of a simulated multi-dimensional scene;

[1(b)] providing lighting data associated with a plurality of simulated light sources arranged to illuminate said scene, said lighting data including light image data;

[1(c)] for each of said plurality of light sources, comparing at least a portion of said observer data with at least a portion of said lighting data to determine if a modeled point within said scene is illuminated by said light source and storing at least a portion of said light image data associated with said point and said light source in a light accumulation buffer; and then

[1(d)] combining at least a portion of said light accumulation buffer with said observer data; and

[1(e)] displaying resulting image data to a computer screen.

(Emphasis added).

The parties agreed to the construction of the term “observer data” as meaning “data representing at least the color of objects in a simulated multi-dimensional scene as viewed from an observer’s perspective.” The district court adopted this construction. Based on this construction and the plain and ordinary meaning of the limitation “said observer data” in step 1(d), Activision filed a motion for summary judgment of non-infringement, and the district court granted the summary judgment.

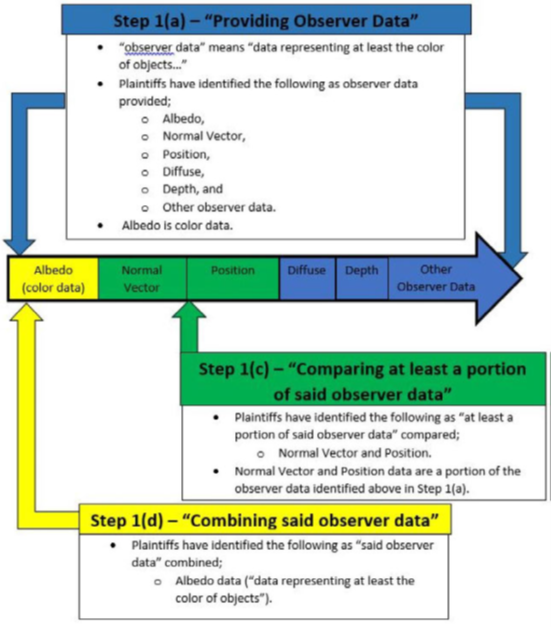

On appeal, Infernal argued that the district court misapplied its own construction of “observer data.” Infernal argued that “observer data” can refer to different data sets in steps 1(a), 1(c) and 1(d), each different data set independently satisfying the “observer data” construction. Step 1(a) recites “providing observer data,” step 1(c) recites “comparing at least a portion of said observer data,” and step 1(d) recites “combining … with said observer data.” The reason Infernal applies this construction is due to their infringement theory summarized below:

In its infringement theory, for step 1(a) Infernal refers to albedo (color data), normal vector, position, diffuse, depth, and other observer data; for step 1(c), Infernal refers to normal vector and position data; and for step 1(d), Infernal refers to only albedo data. Thus, Infernal’s infringement theory relies on applying different obverser data for steps 1(a), 1(c) and 1(d). Infernal argued that “said observer data” in step 1(d) can refer to a narrower set of data than “observer data” in step 1(a) because both independently meet the district court’s construction of “observer data.”

In analyzing Infernal’s argument, the CAFC stated the principal that “[in] grammatical terms, the instances of [‘said’] in the claim are anaphoric phrases, referring to the initial antecedent phrase” citing Baldwin Graphic Sys., Inc. v. Siebert, Inc., 512 F.3d 1338, 1342 (Fed. Cir. 2008). The CAFC further stated that based on this principle, the term “said observer data” recited in steps 1(c) and 1(d) must refer back to the “observer data” recited in step 1(a), and concluded that “the ‘observer data’ in step 1(a) must be the same “observer data” in steps 1(c) and 1(d).” The CAFC stated that this analysis applies even though the district court’s construction of “observer data” encompasses “at least color data.” In concluding that term “observer data” cannot refer to different data among steps 1(a), 1(c) and 1(d), the CAFC stated:

Although the initial “observer data” in step 1(a) includes data that is “at least color data,” the use of the word “said” indicates that each subsequent instance of “said observer data” must refer back to the same “observer data” initially referred to in step 1(a). An open-ended construction of “observer data” (“data representing at least the color of objects”) does not permit each instance of “observer data” in a claim to refer to an independent set of data.

Regarding the district court’s finding that Infernal failed to raise a genuine issue of material fact, Infernal argued that the district court erred in its finding that the accused video games cannot perform the claimed steps in the specified sequence. The district court held that Infernal failed to raise a genuine issue of material fact as to the accused games performing limitation 1(d): “combining … with said observer data.”

The CAFC agreed with the district court. Referring to Infernal’s infringement theory diagram, the CAFC stated that for step 1(a), Infernal identified “observer data” as albedo (color data), normal vector, position, diffuse, depth, and other observer data, but for step 1(d), Infernal identified “said observer data” as only albedo (color data). “Because it is undisputed that the mapping of the Accused Games’s ‘observer data’ in step 1(a) is different than the mapping of the “observer data” in step 1(d), … there is no genuine issue of material fact as to whether the Accused Games infringe [step 1(d)].” The CAFC also pointed out that Infernal’s mapping for step 1(d) improperly excludes data that is mapped to “a portion of said observer data” in step 1(c).

Comments

In a footnote, the CAFC stated that this analysis is consistent with other cases in which the use of the word “said” or “the” refers back to the initial limitation, “even when the initial limitation refers to one or more elements.” When drafting claims, if you intend for a later recitation of the same limitation to refer to an independent instance of the limitation, then you will need to modify the language rather than merely using “said” or “the.”

It appears that if step 1(d) in Infernal’s claim referred to “at least a portion of said observer data,” Infernal would have had a better argument that the observer data in step 1(d) can be a narrower data set than the “observer data” in step 1(a). The CAFC also pointed out that Infernal knew how to do this because that is what they did in step 1(c) and chose not to in step 1(d).

CAFC splits the difference between VLSI and Intel on Claim Construction

| December 28, 2022

VLSI Technology LLC v. Intel Corp.

Decided: November 15, 2022

CHEN, BRYSON, and HUGHES. Opinion by Bryson

Summary:

The Court affirmed the PTAB’s claim construction which had narrowed an interpretation taken from the related District Court’s construction and remanded on a separate claim construction for reading a “used for” aspect out of the claim.

Background:

Intel filed three IPR’s against VLSI’s U.S. Patent No. 7,247,552 (“the ’552 patent”). The ’552 patent is directed to the structures of an integrated circuit that reduce the potential for damage to the interconnect layers and dielectric material when the chip is attached to another electronic component. The two representative claims were claim 1 directed to a device and claim 20 directed to a method. The terms subject to construction are emphasized below.

1. An integrated circuit, comprising:

a substrate having active circuitry;

a bond pad over the substrate;

a force region at least under the bond pad characterized by being susceptible to defects due to stress applied to the bond pad;

a stack of interconnect layers, wherein each interconnect layer has a portion in the force region; and

a plurality of interlayer dielectrics separating the interconnect layers of the stack of interconnect layers and having at least one via for interconnecting two of the interconnect layers of the stack of interconnect layers;

wherein at least one interconnect layer of the stack of interconnect layers comprises a functional metal line underlying the bond pad that is not electrically connected to the bond pad and is used for wiring or interconnect to the active circuitry, the at least one interconnect layer of the stack of interconnect layers further comprising dummy metal lines in the portion that is in the force region to obtain a predetermined metal density in the portion that is in the force region.

20. A method of making an integrated circuit having a plurality of bond pads, comprising:

developing a circuit design of the integrated circuit;

developing a layout of the integrated circuit according to the circuit design, wherein the layout comprises a plurality of metal-containing interconnect layers that extend under a first bond pad of the plurality of bond pads, at least a portion of the plurality of metal-containing interconnect layers underlying the first bond pad and not electrically connected to the bond pad as a result of being used for electrical interconnection not directly connected to the bond pad;

modifying the layout by adding dummy metal lines to the plurality of metal-containing interconnect layers to achieve a metal density of at least forty percent for each of the plurality of metal-containing interconnect layers; and

forming the integrated circuit comprising the dummy metal lines.

VLSI had brought suit in the District of Delaware, charging Intel with infringing the ’552 patent. The District court construed the term “force region,” referencing the specification of the ’552 patent to mean a “region within the integrated circuit in which forces are exerted on the interconnect structure when a die attach is performed.” In the IPRs Intel proposed a construction of “force region” that was consistent with that adopted by the district court and VLSI did not oppose Intel’s proposed construction before the Board.

However, in the course of the IPR proceedings it became apparent that they disagreed as to the meaning of the term “die attach” as set forth in the District court construction.

Intel argued that the term “die attach” refers to any method of attaching the chip to another electronic component, and that the term “die attach” therefore includes attachment by a method known as wire bonding. VLSI argued that the term “die attach” refers to a method of attachment known as “flip chip” bonding, and does not include wire bonding.

The construction was paramount to claim 1 as applying its proposed restrictive definition of “die attach,” VLSI distinguished Intel’s principal prior art reference for the “force region” limitation, U.S. Patent Publication No. 2004/0150112 (“Oda”). Oda discloses attaching a chip to another component using wire bonding but not the flip chip process.

The Board sided with Intel that wire bonding is a type of die attach, and that Oda therefore disclosed a “force region”. Specifically, the Board found that the ’552 patent specification made clear in several places that the term “force region” was not limited to flip chip bonding, but could include wire bonding as well. Based on that finding, the Board concluded that Oda disclosed the “force region” element of claim 1 and was unpatentable for obviousness.

Regarding claim 20 of the ’552 patent, the parties disagreed over the construction of the limitation providing that the “metal-containing interconnect layers” are “used for electrical interconnection not directly connected to the bond pad.” VLSI argued that the phrase requires a connection to active circuitry or the capability to carry electricity. Intel argued that the claim does not require that the interconnection actually carry electricity.

The Board again sided with Intel, asserting the principally relied upon U.S. Patent No. 7,102,223 (“Kanaoka”) teaches the “used for electrical interconnection” limitation. The Board cited to figure 45 of Kanaoka for its disclosure of a die that has a series of interconnect layers, some of which are connected to each other.

VLSI appealed.

CAFC Decision:

VLSI argued that the Board erred in its treatment of the “force region” limitation in claim 1 and in construing the phrase “used for electrical interconnection” in claim 20 to encompass a metallic structure that is not connected to active circuitry.

Claim 1

Regarding the “force region” limitation, VLSI argued that the Board failed to acknowledge and give appropriate weight to the district court’s claim construction. In particular, VLSI based its argument principally on the requirement that the Board “consider” prior claim construction determinations by a district court and give such prior constructions appropriate weight.

However, the CAFC found that the Board was clearly well aware of the district court’s construction, as it was the subject of repeated and extensive discussion in the briefing and in the oral hearing before the PTAB. Further, the Court found that the Board did not reject the district court’s construction, but rather the district court’s construction concealed a fundamental disagreement between the parties as to the proper construction of “force region.”

They held that although the district court defined the term “force region” with reference to “die attach” processes, the district court did not decide— and was not asked to decide—whether the term “die attach,” as used in the patent, included wire bonding or was limited to flip chip bonding. Thus, the CAFC found that the Board addressed an argument not made to the district court, and it reached a conclusion not at odds with the conclusion reached by the district court.

In reaching their decision, the Court noted that other language in the specification of the ‘552 patent indicates that the claimed “force region” is not limited to attachment processes that use flip chip bonding. Restating precedence that claims should not be limited “to preferred embodiments or specific examples in the specification,” they emphasized that even if the term “die attach,” was used in one section of the specification to refer to flip chip bonding in particular other portions of the specification did make clear that the invention was not intended to be limited to flip chip bonding.

VLSI further contended that defining “force region” to mean a region at least directly under the bond pad is legally flawed because the definition restates a requirement that is already in the claims. The Court noted that although caselaw has emphasized redundant construction should not be used, in this case intrinsic evidence makes it clear that the “redundant” construction is correct. Specifically, they stated that the “force region” limitation is best understood as containing a definition of the force region, (“… just as would be the case if the language of the limitation had read ‘a region, referred to as a force region, at least under the bond pad . . .’ or ‘a force region, i.e., a region at least under the bond pad . . . .’), and concluded that the language “is best viewed not as redundant, but merely as clumsily drafted.”

Additionally, VLSI argued the Board was bound by the district court’s and the parties’ agreed upon claim construction, regardless of whether the construction to which the parties agree is actually the proper construction of that term, citing the Supreme Court’s decision in SAS Institute v. Iancu, 138 S. Ct. 1348 (2018), and the CAFC’s decisions in Koninklijke Philips N.V. v. Google LLC, 948 F.3d 1330 (Fed. Cir. 2020), and In re Magnum Oil Tools International, Ltd., 829 F.3d 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

The Court rejected VLSI’s interpretation of the precedent set by the cases. Instead, they noted that each of these cases in fact stands for the proposition that the petition defines the scope of the IPR proceeding and that the Board must base its decision on arguments that were advanced by a party and to which the opposing party was given a chance to respond. They affirmatively stated that none of the relied upon cases prohibits the Board from construing claims in accordance with its own analysis and may adopt its own claim construction of a disputed claim term. Specifically, as to the case at hand, they noted the parties’ very different understandings of the meaning of the term “die attach,” and that it was clear in the Board proceedings that there was no real agreement on the proper claim construction. They conclude that in such a situation, it was proper for the Board to adopt its own construction of a disputed claim term.

Based thereon, the Court affirmed the claim construction of “force region” and the PTAB’s application of the Oda prior art reference.

Claim 20

Regarding claim 20, VLSI argued that the Board erred in construing the phrase “used for electrical interconnection not directly connected to the bond pad,”. As noted above, the Board had held that this phrase encompasses interconnect layers that are “electrically connected to each other but not electrically connected to the bond pad” or to any other active circuitry. VLSI asserted that under its proposed construction, the Kanaoka reference does not disclose the “used for electrical interconnection” limitation of claim 20, because the metallic layers are connected by the vias only to one another; they do not carry electricity and are not electrically connected to any other components.

The Court agreed with VLSI that the Board’s construction of the phrase “used for electrical interconnection not directly connected to the bond pad” was too broad, noting that two aspects of the claim make this point clear. First, the use of the words “being used for” in the claim imply that some sort of actual use of the metal interconnect layers to carry electricity is required. Second, the recitation of “dummy metal lines” elsewhere in claim 20 implies that the claimed “metal-containing interconnect layers” are capable of carrying electricity; otherwise, there would be no distinction between the dummy metal lines and the rest of the interconnect layer. The Court further noted that the file history of the ’552 patent and amendments made during prosecution provided additional support for this conclusion.

Furthermore, they noted that the phrase “as a result of being used for electrical interconnection not directly to the bond pad” was meant to serve some purpose and should be construed to have some independent meaning, citing Merck & Co. v. Teva Pharms. USA, Inc., 395 F.3d 1364, 1372 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (“A claim construction that gives meaning to all the terms of the claim is preferred over one that does not do so.”). Thus, they concluded that the words “being used for” imply that the interconnect layers are at least capable of carrying electricity.

The Court therefore remanded the patentability determination of claim 20 to the Board to assess Intel‘s obviousness arguments in light of their new construction of the “used for electrical interconnection” limitation.

Take away

The PTAB is not hamstrung by prior claim construction reached in a District Court action. The Board may construe claims in accordance with its own analysis and may adopt its own claim construction of a disputed claim term.

The recitation of an operational function (“being used for”) in a claim should not be ignored in claim construction. The claim language should be taken as a whole and other aspects of the claim (“dummy metal lines”) which infer an interpretation should be considered.

No Shapeshifting Claims Through Argument in an IPR

| December 15, 2022

CUPP Computing AS v. Trend Micro Inc.

Decided: November 16, 2022

Circuit Judges Dyk, Taranto and Stark. Opinion by Dyk.

Summary:

CUPP appeals three inter partes review (“IPR”) decisions of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”), largely due to an issue of claim construction. The three patents at issue are U.S. Patents Nos. 8,631,488 (“’488 patent”), 9,106,683 (“’683 patent”), and 9,843,595 (“’595 patent”). The contested claim construction involves the limitation concerning a “security system processor,” which appears in every independent claim in each of the three patents.

The limitation in question reads in part “the mobile device having a mobile device processor different than the mobile security system processor”.

Trend Micro petitioned the Board for inter partes review of several claims in the ’488, ’683, and ’595 patents, arguing that the claims were unpatentable as obvious over two individual prior art references. CUPP responded that the security system processor limitation required that the security system processor be “remote” from the mobile device processor, and that neither of the cited references disclosed this limitation because both taught a security processor bundled within a mobile device.

The Board instituted review and, in three final written decisions, found all the challenged claims obvious over the prior art. Specifically, the Board held that the challenged claims did not require that the security system processor be remote from the mobile device processor, but merely that the mobile device has a mobile device processor different than the mobile security system processor.

That is, the fact that the security system processor is “different” than the mobile device processor does not suggest that the two processors are remote from one another. Rather, citing Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, the Board and the CAFC noted that the ordinary meaning of “different” is simply “dissimilar.” The CAFC further noted that CUPP had given no reason to apply a more specialized meaning to the word.

Furthermore, the CAFC drew support from the specification of each of the three Patents. Briefly, that in one “preferred embodiment” each of the patents described that the mobile security system may be incorporated within the mobile device. Thus, the CAFC concluded that “highly persuasive” evidence would be required to read claims as excluding a preferred embodiment of the invention. Vitronics Corp. v. Conceptronic, Inc., 90 F.3d 1576, 1583–84 (Fed. Cir. 1996). Indeed, “a claim interpretation that excludes a preferred embodiment from the scope of the claim is rarely, if ever, correct.” Accent Pack-aging, Inc. v. Leggett & Platt, Inc., 707 F.3d 1318, 1326 (Fed. Cir. 2013) (citation omitted).

CUPP responds that, because at least one independent claim in each of the patents requires the security system to send a signal “to” the mobile device, and “communicate with” the mobile device, the system must be remote from the mobile device processor.

The CAFC were not persuaded holding that the Board properly construed the security system processor limitation in line with the specification. The CAFC analogized that “just as a person can send an email to him- or herself, a unit of a mobile device can send a signal “to,” or “communicate with,” the device of which it is a part.”

Next, CUPP argued that, because it disclaimed a non-remote security system processor during the initial examination of one of the patents at issue, the Board’s construction is erroneous. The CAFC held that the Board properly rejected that argument, because CUPP’s disclaimer did not unmistakably renounce security system processors embedded in a mobile device. Rather, the CAFC upheld the Board’s reading of CUPP’s remarks during prosecution as a “reasonable interpretation[]” that defeats CUPP’s assertion of prosecutorial disclaimer. Avid Tech., Inc., 812 F.3d at 1045 (citation omitted); see also J.A. 20–22.

Briefly, during prosecution of the ’683 patent, the Patent Office examiner found all claims in the application obvious in light of the prior art. CUPP’s responded that if the TPM “were implemented as a stand-alone chip attached to a PC mother-board,” it would be “part of the motherboard of the mobile devices” rather than being a separate processor. J.A. 3578. The TPM would therefore not constitute “a mobile security system processor different from a mobile system processor.”

The Board found, and the CAFC upheld, that under one plausible reading, CUPP’s point was that the prior art failed to teach different processors because the TPM lacks a distinct processor. Thus, under this interpretation, if the TPM were “a stand-alone chip attached to a . . . motherboard,” it would rely on the motherboard’s processor, and not have its own different processor. For this reason, the CAFC concluded that CUPP’s comment to the examiner is consistent with it retaining claims to security system processors embedded in a mobile device with a separate processor.

Lastly, CUPP contended that the Board erred by rejecting CUPP’s disclaimer in the IPRs themselves, disavowing a security system processor embedded in a mobile device.

Here, the CAFC unambiguously stated that it was making “precedential the straightforward conclusion [they] drew in an earlier nonprecedential opinion: “[T]he Board is not required to accept a patent owner’s arguments as disclaimer when deciding the merits of those arguments.” VirnetX Inc. v. Mangrove Partners Master Fund, Ltd., 778 F. App’x 897, 910 (Fed. Cir. 2019). That a rule permitting a patentee to tailor its claims in an IPR through argument alone would substantially undermine the IPR process. Congress designed inter partes review to “giv[e] the Patent Office significant power to revisit and revise earlier patent grants,” thus “protect[ing] the public’s paramount interest in seeing that patent monopolies are kept within their legitimate scope.” If patentees could shapeshift their claims through argument in an IPR, they would frustrate the Patent Office’s power to “revisit” the claims it granted, and require focus on claims the patentee now wishes it had secured. See also Oil States Energy Servs., LLC v. Greene’s Energy Grp., LLC, 138 S. Ct. 1365, 1373 (2018).

Thus, to conclude, a disclaimer in an IPR proceeding is only binding in later proceedings, whether before the PTO or in court. The CAFC emphasized that congress created a specialized process for patentees to amend their claims in an IPR, and CUPP’s proposed rule would render that process unnecessary because the same outcome could be achieved by disclaimer. See 35 U.S.C. § 316(d).

Take-away:

- A disclaimer in an IPR proceeding is only binding in later proceedings, whether before the PTO or in court.

- A claim interpretation that excludes a preferred embodiment from the scope of the claim is rarely, if ever, correct.

- Disclaimers made during prosecution must be clear and unmistakable to be relied upon later. Specifically: “The doctrine of prosecution disclaimer precludes patentees from recapturing through claim interpretation specific meanings disclaimed during prosecution.” Mass. Inst. of Tech. v. Shire Pharms., Inc., 839 F.3d 1111, 1119 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (ellipsis, alterations, and citation omitted). However, a patentee will only be bound to a “disavowal [that was] both clear and unmistakable.” Id. (citation omitted). Thus, where “the alleged disavowal is ambiguous, or even amenable to multiple reasonable interpretations, we have declined to find prosecution disclaimer.” Avid Tech., Inc. v. Harmonic, Inc., 812 F.3d 1040, 1045 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

- Claim terms are given their ordinary meaning unless persuasive reason is provided to apply a more specialized meaning to the word.

The applicants’ statement during the prosecution may play a critical role for claim construction

| July 4, 2022

Sound View Innovations, LLC v. Hulu, LLC

Decided: May 11, 2022

Prost, Mayer (Sr.) and Taranto. Court opinion by Taranto.

Summary

On appeals from the district court for summary judgment of noninfringement of a patent, directed to a method of reducing latency in a network having a content server, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s construction of the down-loading/retrieving limitation solely on the basis of prosecution history, but the Court rejected the district court’s determination that “buffer” cannot cover “a cache,” and vacated the district court’s grant of summary judgment and remanded for further proceedings.

Details

I. Background

(i) The Patent in Dispute

Sound View Innovations, LLC (“Sound View”) owns now-expired U.S. Patent No. 6,708,213 (“the ’213 patent”), which describes and claims “methods which improve the caching of streaming multimedia data (e.g., audio and video data) from a content provider over a network to a client’s computer.” Claim 16 of the ’213 patent provides as follows:

16. A method of reducing latency in a network having a content server which hosts streaming media (SM) objects which comprise a plurality of time-ordered segments for distribution over said network through a plurality of helpers (HSs) to a plurality of clients, said method comprising:

receiving a request for an SM object from one of said plurality of clients at one of said plurality of helper servers;

allocating a buffer at one of said plurality of HSs to cache at least a portion of said requested SM object;

downloading said portion of said requested SM object to said requesting client, while concurrently retrieving a remaining portion of said requested SM object from one of another HS and said content server (the “downloading/retrieving limitation”); and

adjusting a data transfer rate at said one of said plurality of HSs for transferring data from said one of said plurality of helper servers to said one of said plurality of clients (emphasis added).

During the prosecution, the examiner rejected original claim 16—which was identical to issued claim 16 except that it lacked the downloading/retrieving limitation—as anticipated over DeMoney (U.S. Patent No. 6,438,630). To overcome the rejection, the applicants amended the claim to add the downloading/retrieving limitation. The applicants explained that support for the added limitation is found in the applicants’ specification, pointing to the portion of the specification that shows concurrent downloading and retrieval involving a single buffer (emphasis added). In fact, the specification nowhere says that the invention includes use of separate buffers for the concurrent downloading and retrieving functions, and it nowhere illustrates or describes such an embodiment, in which different buffers are involved in con- current downloading of one portion and retrieving of a remaining portion of the same SM object in response to a given client’s request.

(ii) The District Court

Sound View sued Hulu, LLC (“Hulu”) for infringement of six Sound View patents including the ’213 patent in the United States District Court for the Central District of California (“the district court”). As the case proceeded, only claim 16 of the ’213 patent remained at issue.

It was undisputed that the accused edge servers— the edge servers Sound View identified as the “helper servers” for its infringement charge—do NOT download and retrieve subsequent portions of the same SM object in the same buffer (emphasis added).

Sound View alleged, among other things, that, under Hulu’s direction, when an edge server receives a client request for a video not already fully in the edge server’s possession, and obtains segments of the video seriatim from the content server (or another edge server), the edge server transmits to the Hulu client a segment it has obtained while concurrently retrieving a remaining segment.

The district court agreed with Hulu’s argument that the applicants’ statements accompanying the amendment in the prosecution disclaimed the full scope of the downloading/retrieving limitation, and that the downloading/retrieving limitation thus required that the same buffer in the helper server—the one allocated in the preceding step—host both the portion sent to the client and a remaining portion retrieved concurrently from the content server or other helper server (emphasis added).

In reliance on the construction, Hulu then sought summary judgment of non-infringement of claim 16, arguing that it was undisputed that, in the edge servers of its content delivery networks, no single buffer hosts both the video portion downloaded to the client and the retrieved additional portion. Sound View countered that there remained a factual dispute about whether “caches” in the edge servers met the concurrency limitation as construed. The district court held, however, that a “cache” could not be the “buffer” that its construction of the down- loading/retrieving limitation required, and on that basis, it granted summary judgment of non-infringement. A final judgment followed.

Sound View timely appealed.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit (“the Court”) affirmed the district court’s construction of the down-loading/retrieving limitation. but the Court rejected the district court’s determination that “buffer” cannot cover “a cache,” and vacated the district court’s grant of summary judgment and remanded for further proceedings.

Claim Construction (the downloading/retrieving limitation)

The Court first noted that this is not a case in which the other intrinsic evidence—the claim language and specification—establish a truly plain meaning contrary to the meaning assertedly established by the prosecution history because the downloading/retrieving limitation, which does not expressly refer to “buffers,” contains no words affirmatively making clear that different buffers in the helper server may be used for the sending out to clients of one portion of the SM object and the receiving of a retrieved remaining portion.

The Court viewed the prosecution history as establishing that the applicants made clear that the applicants’ invention concurrently empties and fills the buffer, while the DeMoney reference teaches filling the buffer only after the buffer is empty,” citing column 12, lines 28–40 of DeMoney (emphasis added).

Based on the applicants’ statements, the Court agreed with the district court that the applicants limited claim 16 to using the same buffer for the required concurrent downloading and retrieval of portions of a requested SM object.

Summary Judgment of Non-Infringement

After the district court adopted its “buffer”-requiring claim construction of the downloading/retrieving limitation, it granted summary judgment of non-infringement, concluding that accused-system components called “caches”—on which Sound View relied for its allegation of infringement under the court’s claim construction—could not be the required “buffers.” The district court relied for its conclusion on the ’213 patent’s references to its described “buffers” and “caches” as distinct physical components. To support the conclusion, the district court noted that the ’213 patent describes buffers and caches in different locations: The patent defines “cache” as “a region on the computer disk that holds a subset of a larger collection of data,” and although the patent does not define “buffer,” it describes “ring buffers” located “in the memory” of the HS.

However, the Court stated that the district court’s construction here was inadequate for the second step of an infringement analysis (comparison to the accused products or methods) because it did not adopt an affirmative construction of what constitutes a “buffer” in this patent. More specifically, the Court stated that the district court did not decide, and the record does not establish, that “cache” is a term of such uniform meaning in the art that its meaning in the ’213 patent must be relevantly identical to its meaning when used by those who labeled the pertinent components of the accused edge servers. The Court thus concluded that, in the absence of such a uniformity-of-meaning determination, the district court’s conclusion that the ’213 patent distinguishes its buffers and caches is insufficient to support a determination that the accused-component “caches” are outside the “buffers” of the ’213 patent. What was needed was an affirmative construction of “buffer”— which could then be compared to the accused-component “caches” based on more than a mere name.

For an additional reason for the further affirmative construction, the Court pointed out that, even in the ’213 patent, the terms “buffer” and “cache” do not appear to be mutually exclusive, but instead seem to have at least some overlap in their coverage given that the disputed claim describes “allocating a buffer . . . to cache” a portion of the SM object, and that the specification explains that “the ring buffer . . . operates as a type of short term cache” because it is capable of servicing multiple client requests within a certain time interval (emphasis added).

Takeaway

· Claim construction: The applicants’ statement during the prosecution may play a critical role for claim construction if the claim language and specification do not establish a truly plain meaning of a disputed term contrary to the meaning assertedly established by the prosecution history.

· Summary Judgment: Portions of the specification may provide genuine issue of material fact for denial of summary judgment (in this case, the embodiment describes buffers and caches in different locations while the disputed claim provides “allocating a buffer . . . to cache”)

Claim differentiation helps broaden the scope of a claim to a Fuse end cap

| April 29, 2022

Littlefuse, Inc. v. Mersen USA EP Corp.

Decided: April 4, 2022

Prost, Bryson and Stoll. Opinion by Bryson.

Summary:

Littlefuse sued Mersen for infringement of its patent to a fuse end cap. In construing the claims, the district court held that the claims are limited to a multi-piece apparatus even though some dependent claims recite a single-piece apparatus. Upon review of the claims, specification, and prosecution history, and based on principles of claim differentiation, the CAFC concluded that the district court’s construction is incorrect. The CAFC concluded that the independent claims should be construed as including multi-piece fuse end caps as well as single-piece fuse end caps. Thus, the CAFC vacated the district court’s judgment and remanded.

Details:

Littlefuse owns U.S. Patent No. 9,564,281 to a “fuse end cap for providing an electrical connection between a fuse and an electrical conductor.” Independent claim 1 is provided:

1. A fuse end cap comprising:

a mounting cuff defining a first cavity that receives an end of a fuse body, the end of the fuse body being electrically insulating;

a terminal defining a second cavity that receives a conductor, wherein the terminal is crimped about the conductor to retain the conductor within the second cavity; and

a fastening stem that extends from the mounting cuff and into the second cavity of the terminal that receives the conductor.

Dependent claims 8 and 9 are also important in this case and are provided:

8. The fuse end cap of claim 1, wherein the mounting cuff and the terminal are machined from a single, contiguous piece of conductive material.

9. The fuse end cap of claim 1, wherein the mounting cuff and the terminal are stamped from a single, contiguous piece of conductive material.

The specification describes three embodiments: (1) a “machined end cap” that may be manufactured from a single piece of any suitable, electrically conductive material; (2) a “stamped end cap” that may be manufactured from a single piece of any suitable, electrically conductive material; and (3) an “assembled end cap” in which the terminal and mounting cuff are formed from separate pieces of material, the material being any suitable, electrically conductive material. With the “assembled end cap,” the terminal and mounting cuff are “joined together, such as by press-fitting a fastening stem of the mounting cuff into the cavity of the terminal” or by using “a variety of other fastening means including … various adhesives, various mechanical fasteners, or welding.”

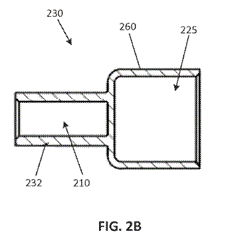

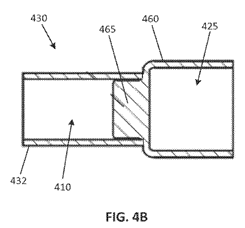

The following is an example of the “machined fuse end cap”:

And the following is an example of the “assembled end cap”:

During prosecution, the Examiner issued a restriction requirement stating that each of the three embodiments represented a distinct species. Littlefuse elected to prosecute the species corresponding to the “assembled end cap” embodiment. Claims 8 and 9 directed to the “machined end cap” and the “stamped end cap,” respectively, were then withdrawn. These dependent claims were subject to reinstatement if a generic claim was found to be allowable. Upon a rejection issued by the Examiner, claim 1 was amended to include the “fastening stem” limitation shown above. Amended claim 1 was then allowed and claims 8 and 9 were rejoined since the Examiner concluded that claims 8 and 9 require all the limitations of the allowable claims.

District Court

In the district court, the term “fastening stem” was construed to mean “a stem that attaches or joins other components”; and “a fastening stem that extends from the mounting cuff and into the second cavity of the terminal that receives the conductor” was construed to mean “a stem that extends from the mounting cuff and into the second cavity of the terminal that receives the conductor, and attaches the mounting cuff to the terminal.” The district court further construed claim 1 such that the fuse end cap “is of multi-piece construction” and that claim 1 does not cover a single-piece apparatus. The parties stipulated to non-infringement based on the district court’s construction of claim 1 as covering only a multi-piece apparatus, and Littlefuse appealed the claim construction ruling.

CAFC

The court first explained claim construction principles citing Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (en banc) stating that “A claim term is generally given the meaning that the term would have to a person of ordinary skill in the art in question at the time of the invention” and that “How the term is used in the claims and the specification of the patent is strong evidence of how a person of ordinary skill would understand the term.”

The court further stated that “The structure of the claims is enlightening.” Citing Baxalta Inc. v. Genentech, Inc., 972 F.3d 1341 (Fed. Cir. 2020), the court stated that “By definition, an independent claim is broader than a claim that depends from it, so if a dependent claim reads on a particular embodiment of the claimed invention, the corresponding independent claim must cover that embodiment as well.” The court stated that if this were not the case, then the dependent claim would be meaningless, and a claim construction that leads to that result is generally disfavored. Thus, the court concluded that the recitation of a single-piece apparatus in claims 8 and 9 is persuasive evidence that claim 1 also covers a single-piece apparatus.

The court then explained principles regarding claim-differentiation stating that “the presumption of differentiation in claim scope is not a hard and fast rule” citing Seachange Int’l, Inc. v. C-COR, Inc., 413 F.3d 1361 (Fed. Cir. 2005) and that “any presumption created by the doctrine of claim differentiation will be overcome by a contrary construction dictated by the written description or prosecution history” citing Retractable Techs., Inc. v. Becton, Dickinson, and Co., 653 F.3d 1296 (Fed. Cir. 2011).

Mersen argued that notwithstanding the doctrine of claim differentiation, a construction that renders certain claims superfluous need not be rejected if that construction is consistent with the teachings of the specification citing Marine Polymer Technologies, Inc. v. HenCon, Inc., 672 F.3d 1350 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (en banc). However, the court stated that Littlefuse’s construction is supported by the specification. The court further stated that Mersen’s construction “would not merely render the dependent claims superfluous, but would mean that those claims would have no scope at all, a result that should be avoided when possible.”

The court pointed out that the district court recognized the inconsistency between its construction of claim 1 as covering only a multi-piece apparatus and the recitation of a single-piece apparatus in dependent claims 8 and 9. The district court concluded that the Examiner’s rejoinder of those dependent claims was a mistake. However, the CAFC said that the record in this case does not support the district court’s conclusion. The CAFC agreed with the Examiner that the dependent claims “require all the limitations of the … allowable claims” since the independent claims are not limited to a multi-piece construction and “the dependent claims form a coherent invention in that they each recite a fuse end cap that comprises a mounting cuff, a terminal, and a fastening stem.

The court also addressed the specification which only refers to a “fastening stem” with respect to the “assembled end cap” embodiment, which is a multi-piece apparatus. But the court said that “courts ordinarily should not limit the claimed invention to preferred embodiments or specific examples in the specification.” The court pointed out that the specification does not state that a fastening stem cannot be present in a single-piece apparatus and “one can envision a stem that projects from the side of the mounting cuff even in an embodiment in which the fuse end cap is formed from a single piece of material.”

The court concluded that the construction of “fastening stem” that is most consistent with the claims, specification, and prosecution history is a construction that includes a multi-piece end cap as well as a single-piece end cap. Thus, the court vacated the district court’s judgment of non-infringement and remanded.

Comments

Claim differentiation can be a useful tool for providing broader claim scope to independent claims. Thus, when drafting patent applications, it is a good idea to include various dependent claims.

Also, when faced with a restriction requirement due to distinct species and upon allowance of some claims, make sure to review whether other claims can be rejoined. In this case, the fact that the Examiner rejoined some species claims as being covered by a generic independent claim helped persuade the CAFC to provide a broader construction of the independent claim.

APPLE MAKES ROTTEN CONVINCING THAT THE PTAB CANNOT CONSTRUE CLAIMS PROPERLY

| April 7, 2022

Apple, Inc vs MPH Technologies, OY

Decided: March 9, 2022

MOORE, Chief Judge, PROST and TARANTO. Opinion by Moore.

Summary:

Apple appealed losses on 3 IPRs attempting to convince the CAFC that the PTAB had misconstrued numerous dependent claims for a myriad of reasons. The CAFC sided with the Board on all counts, in general showing deference to the PTAB and its ability to properly interpret claims.

Background:

Apple appealed from 3 IPRs wherein the PTAB had held Apple failed to show claims 2, 4, 9, and 11 of U.S. Patent No. 9,712,494; claims 7–9 of U.S. Patent No. 9,712,502; and claims 3, 5, 10, and 12–16 of U.S. Patent No. 9,838,362 would have been obvious. Apple’s IPR petitions relied primarily on a combination of Request for Comments 3104 (RFC3104) and U.S. Patent No. 7,032,242 (Grabelsky).

The patents disclose a method for secure forwarding of a message from a first computer to a second computer via an intermediate computer in a telecommunication network in a manner that allowed for high speed with maintained security.

The claims of the ’494 and ’362 patents cover the intermediate computer. Claim 1 of the ’494 patent was used as the representative independent claim for the patents:

1. An intermediate computer for secure forwarding of messages in a telecommunication network, comprising:

an intermediate computer configured to connect to a telecommunication network;

the intermediate computer configured to be assigned with a first network address in the telecommunication network;

the intermediate computer configured to receive from a mobile computer a secure message sent to the first network address having an encrypted data payload of a message and a unique identity, the data payload encrypted with a cryptographic key derived from a key exchange protocol;

the intermediate computer configured to read the unique identity from the secure message sent to the first network address; and

the intermediate computer configured to access a translation table, to find a destination address from the translation table using the unique identity, and to securely forward the encrypted data payload to the destination address using a network address of the intermediate computer as a source address of a forwarded message containing the encrypted data payload wherein the intermediate computer does not have the cryptographic key to decrypt the encrypted data payload.

The ’502 patent claims the mobile computer that sends the secure message to the intermediate computer.

Decision:

The Court first looked at dependent claim 11 of the ’494 patent and dependent claim 12 of the ’362 patent requirement that “the source address of the forwarded message is the same as the first network address.”

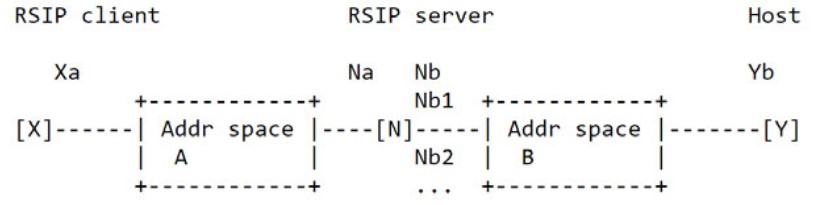

Apple had asserted RFC3104 disclosed this aspect of the claims. Specifically, RFC3104 discloses a model wherein an RSIP server examines a packet sent by Y destined for X. “X and Y belong to different address spaces A and B, respectively, and N is an [intermediate] RSIP server.” N has two addresses: Na on address space A and Nb on address space B, which are different. Apple asserted the message sent from Y to X is received by RSIP server N on the Nb interface and then must be sent to Na before being forwarded to X.

The model topography for RFC3104 is illustrated as:

In light thereof, Apple asserted that because the intermediate computer sends the message from Nb to Na before forwarding it to X, Na is both a first network address and the source address of the forwarded message. That the message was not sent directly to Na, Apple claimed, was of no import given the claim language. The Board had disagreed and found there was no record evidence that the mobile computer sent the message directly to Na.

In the appeal, Apple argued the Board misconstrued the claims to require that the mobile computer send the secure message directly to the intermediate computer. Rather, Apple asserted, the mobile computer need not send the message to the first network address so long as the message is sent there eventually. Specifically, Apple emphasized that the PTAB’s construction is inconsistent with the phrase “intermediate computer configured to receive from a mobile computer a secure message sent to the first network address” in claim 1 of the ’494 patent, upon which claim 11 depends.

The Court construed the plain meaning of “intermediate computer configured to receive from a mobile computer a secure message sent to the first network address” requires the mobile computer to send the message to the first network address. The phrase identifies the sender (i.e., the mobile computer) and the destination (i.e., the first network address). The CAFC maintained that the proximity of the concepts links them together, such that a natural reading of the phrase conveys the mobile computer sends the secure message to the first network address. Thus the CAC agreed with the PTAB that the plain language establishes direct sending.

The Court reenforced their holding by looking to the written description as confirming this plain meaning. Specifically, they noted it describes how the mobile computer forms the secure message with “the destination address . . . of the intermediate computer.” The mobile computer then sends the message to that address. There is no passthrough destination address in the intermediate computer that the secure message is sent to before the first destination address. Accordingly, like the claim language, the written description describes the secure message as sent from the mobile computer directly to the first destination address.

Second, the CAFC examined dependent claim 4 of the ’494 patent is similar to claim 5 of the ’362 patent. Claim 4 of the ‘494 recites:

…wherein the translation table includes two partitions, the first partition containing information fields related to the connection over which the secure message is sent to the first network address, the second partition containing information fields related to the connection over which the forwarded encrypted data payload is sent to the destination address. (emphasis added in opinion).

The Board had interpreted “information fields” in this claim to require “two or more fields.” However, Apple’s obviousness argument relied on Figure 21 of Grabelsky, which disclosed a partition with only a single field. Therefore, the Board found Apple failed to show the combination taught this limitation. Moreover, the Board found Apple failed to show a motivation to modify the combination to use multiple fields.

On claim construction, Apple contended there is a presumption that a plural term covers one or more items. Apple maintained that patentees can overcome that presumption by using a word, like “plurality”, that clearly requires more than one item.

The Court found that Apple misstated the law. In accordance with common English usage, the Court presumes a plural term refers to two or more items. And found that this is simply an application of the general rule that claim terms are usually given their plain and ordinary meaning.

The Court also noted that there is nothing in the written description providing any significance to using a plurality of information fields in a partition. The CAFC therefore found that absent any contrary intrinsic evidence, the Board correctly held that fields referred to more than one field.

Third, the Court looked to Claim 2 of the ’494 patent and claim 3 of the ’362 patent. Claim 2 of the ‘494 states:

…wherein the intermediate computer is further configured to substitute the unique identity read from the secure message with another unique identity prior to forwarding the encrypted data payload. (emphasis added in opinion).

The Board construed the word “substitute” to require “changing or modifying, not merely adding to.” Because it determined that RFC3104 merely involved “adding to” the unique identity, the Board found Apple had failed to show RFC3104 taught this limitation. The Board expressly addressed Apple’s argument from the hearing that “adding the header is the same as replacing the header because at the end of the day you have a different header than what you had before, a completely different header.” The Board disagreed with Apple and construed “substitute” to mean “changing, replacing, or modifying, not merely adding,” and observed that this construction disposed of Apple’s position.

The CAFC found no misconstruction by the PTAB with this interpretation. Moreover, the Court noted tat substantial evidence supports the Board’s finding that Apple failed to show a motivation to modify the prior art combination to include substitution. Apple relied solely on its expert’s contrary testimony, which the Court found the Board had properly disregarded as conclusory.

Fourth, the Court reviewed the PTAB’s interpretation of claim 9 of the ’494 patent, similar to claim 10 of the ’362 patent. Claim 9 of the ‘494 states:

…wherein the intermediate computer is configured to modify the translation table entry address fields in response to a signaling message sent from the mobile computer when the mobile computer changes its address such that the intermediate computer can know that the address of the mobile computer is changed. (emphasis added in opinion).