Prior Art Reference Must Disclose Arrangement of Elements, Not Merely Each Discrete Element

| March 20, 2013

SynQor, Inc., v. Artesyn Technologies, Inc., et al.

March 13, 2013

Panel: Rader, Lourie and Daniel (Chief District Judge). Opinion by Rader.

Summary

SynQor sued Artesyn Technologies, Inc., and eight other power converter manufactures (Defendants) for infringement of five of SynQor’s U.S. Patents in the United States District Court (“DC”) for the Eastern District of Texas. The DC granted partial summary judgment of infringement of against the Defendants. The DC denied Defendants’ motion for judgment as a matter of law (JMOL) or a new trial after the jury found all asserted claims infringed, not invalid, and awarded lost-profits of $95 million. On appeal, the CAFC affirmed the DC based on a review of the record evidence.

Details

POINTS OF LAW

Anticipation requires more than a reference disclosing each discrete element of a claim; the reference must disclose the arrangement of elements required by the claim. A claim construction that “excludes the preferred embodiment is rarely, if ever, correct and would require highly persuasive evidentiary support.” Adams Respiratory Therapeutics, Inc. v. Perrigo Co., 616 F.3d 1283, 1290 (Fed. Cir. 2010).

THE FACTS

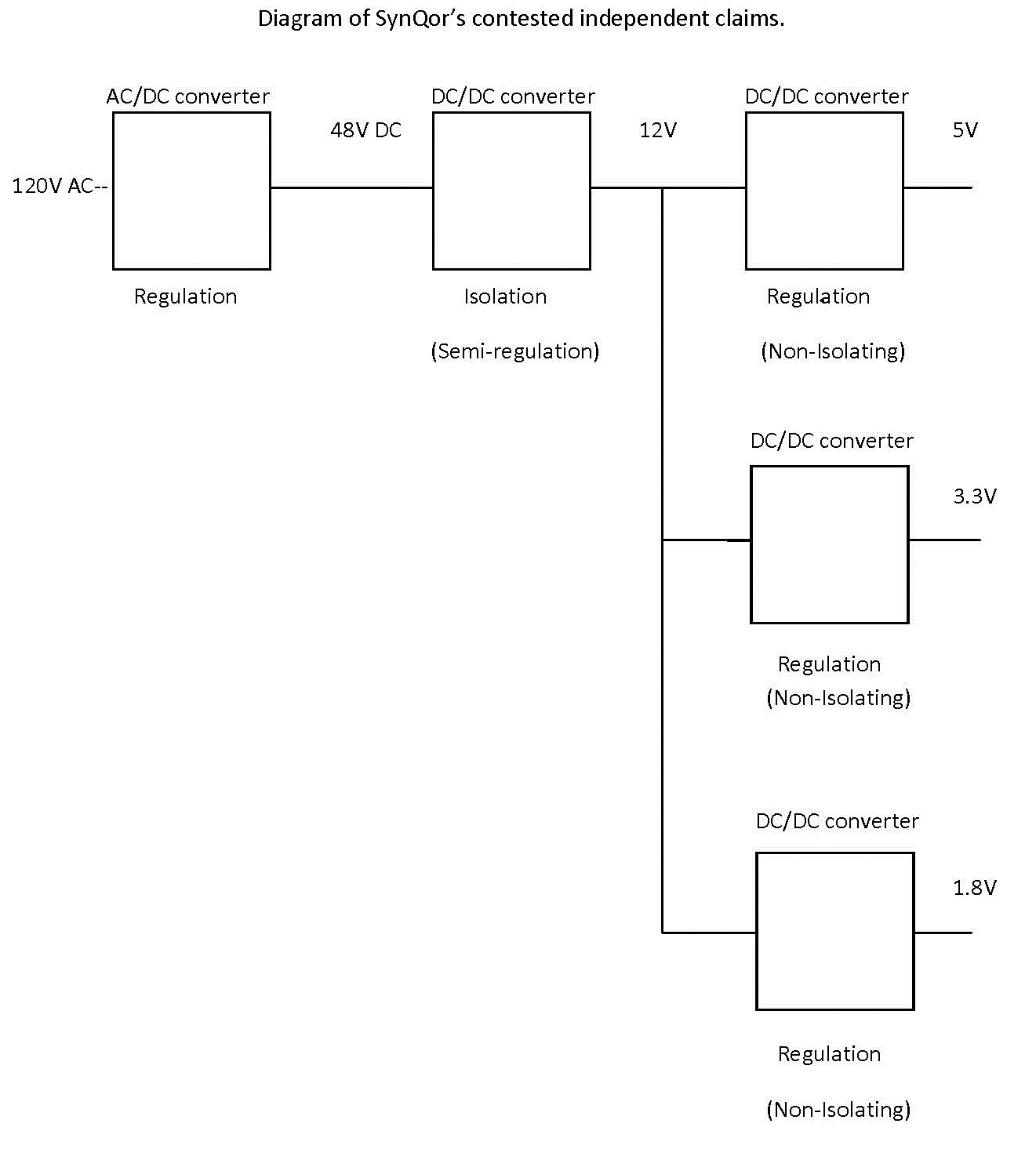

SynQor’s asserted patents relate to a multiple-stage distributed power architecture known as an “intermediate bus architecture” (IBA) used to power circuitry in large computer systems and telecommunication data communication equipment. For example, in an IBA, external power (e.g., 120 volts alternating current (AC)) is first converted to relatively high-voltage DC power (e.g., 48 volts) by a “front end converter.” Next, an “intermediate bus converter” steps down the 48 volt DC power to a lower volt-age (e.g., 12 volts). The intermediate bus converter provides isolation either with no regulation or with semi-regulation. The final stage uses multiple non-isolating regulators to convert 12 volt DC to proper levels for power logic circuitry (e.g., 5 volts). A converter provides “isolation” if its input and output are not directly connected by wires, i.e., by the use of a transformer. A converter provides “regulation” by restricting the output voltage to a desired constant value irrespective of fluctuations in the input voltage.

The diagram below is representative of most of SynQor’s contested independent claims:

AT THE DISTRICT COURT

Anticipation- “A plurality of non-isolating regulation stages”

Each of SynQor’s claims, except one, requires “a plurality of non-isolating regulation stages” that receives the output of a non-regulating isolation stage.

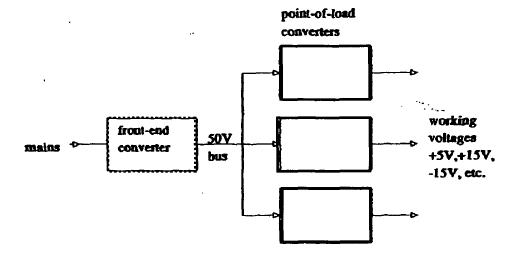

The Defendant asserted that the Mweene Thesis (Thesis) discloses a distributed power architecture having a plurality of non-isolated regulation stages. The Thesis discloses a distributed power architecture including a plurality of point-of-load converters, as shown below:

It is undisputed that the front-end converter is a non-regulating isolation stage. However, Dr. Mweene acknowledged his thesis “did not in detail describe the design of point-of-load converters,” and therefore did not disclose use of a non-isolating switching regulator as a point-of-load regulator. In addition, SynQor’s expert and the inventor testified that the point of load regulators shown had to be isolated.

Defendants asserted that the “point of load converters” are “a plurality of non-isolated regulation stages.” In order to support their position, the Defendants pointed to Mweene’s disclosure of a “buck converter.” Regarding the “buck converter”, while SynQor acknowledged that the buck converter is a non-isolated regulator, SynQor’s experts testified that the Thesis discloses the buck converter only as a simplified model for purposes of a mathematical stability analysis, not as “something you would really use” as a point-of-load converter in a working system.

The jury found that the prior art, the Thesis, did not disclose a plurality of non-isolating regulators that receive the output of a non-regulating isolation stage.

Claim Construction

The district court construed the terms “isolation,” “isolating,” and “isolated,” to mean “the absence of an electric path permitting the flow of DC current (other than a de minimus amount) between an input and an output of a particular stage, component, or circuit.”

Defendants asserted that the construction should require isolation “between two points” rather than “between an input and an output of a particular stage, component, or circuit.” Defendants argued that consumers connect the input and output of the claimed system to a common ground such that the system is not isolated.

AT THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT

Anticipation- “A plurality of non-isolating regulation stages”

The CAFC agreed that the Mweene Thesis discloses a distributed power architecture with a non-regulating isolation stage supplying power to a plurality of regulators, and separately discloses a non-isolating regulator in a simplified mathematical analysis.

Thus, the CAFC concluded that the record contains sufficient evidence to support the jury’s finding that the buck converter discussed by the Mweene Thesis was not disclosed as a point of load converter to be used in an actual system. That is, while the Thesis may disclose each discrete element of SynQor’s claims, the Thesis does not disclose the arrangement of elements as required by the claims.

Claim Construction

The CAFC found that:

In this case, the customary meaning of the contested terms, construed within their proper context in the claim, verifies the trial court’s construction. The term “isolation” is used as an adjective describing a stage or converter within the power converter system. For example, claim 1 of the ‘190 Patent claims “a power converter system comprising: a DC power source; a nonregulating isolation stage . . .; and a plurality of nonisolating regulation stages . . . .” ‘190 Patent col. 17 ll. 22-42 (emphasis added); see also ‘702 Patent col. 22 l. 22 (claiming a system comprising an “isolating step-down converter” and “plural non-isolating . . .regulators“). The claim language thus only requires isolation within a particular stage. Requiring “isolation” between every two points in the system would read the terms “stage” or “converter” out of the claims.

The CAFC noted that “The figures in the specification further support the district court’s construction.” That is, an isolation stage that has no electrical connection between its input and output is clearly shown, while the entire power converter system is not. In other words, SynQor’s patents simply to not disclose whether the input and output grounds of the entire system could be connected to one another.

The CAFC further noted that “Defendants’ expert admitted that construing the claims such that ‘employ[ing] the common technique of grounding the system’ would cause the converter to be considered non-isolated would prevent the claims from encompassing the preferred embodiment.’” A claim construction that “excludes the preferred embodiment is rarely, if ever, correct and would require highly persuasive evidentiary support.” Adams Respiratory Therapeutics, Inc. v. Perrigo Co., 616 F.3d 1283, 1290 (Fed. Cir. 2010).

Thus, the CAFC held that the district court correctly construed “isolation” to require the absence of an electrical path “between the input and output of a particular stage, component, or circuit” and affirmed the grant of partial summary judgment of infringement on this limitation.

Tags: anticipation > claim construction > ThomasBrown