UNEXPECTED RESULTS VERSUS UNEXPECTED MECHANISM

Stephen G. Adrian | July 28, 2023

In Re: John L Couvaras

Decided June 14, 2023

Before Lourie, Dyk and Stoll.

Summary

This precedential decision serves as a good lesson on what is necessary to overcome an obviousness rejection based on unexpected results. The applicant in this decision, however, failed to overcome the rejection due to arguing an unexpected mechanism instead of unexpected results.

Background

The applicant appeals a decision from the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) affirming the Examiner’s rejection of the pending claims as obvious over prior art. Representative claim 11 recites:

11. A method of increasing prostacyclin release in systemic blood vessels of a human individual with essential hypertension to improve vasodilation, the method comprising the steps of:

providing a human individual expressing GABA-a receptors in systemic blood vessels due to essential hypertension;

providing a composition of a dosage of a GABA-a agonist and a dosage of an ARB combined into a deliverable form, the ARB being an Angiotensin II, type 1 receptor antagonist;

delivering the composition to the human individual’s circulatory system by co-administering the dosage of a GABA-a agonist and the dosage of the ARB to the human individual orally or via IV;

synergistically promoting increased release of prostacyclin by blockading angiotensin II in the human individual through the action of the dosage of the ARB to reduce GABA-a receptor inhibition due to angiotensin II presence during a period of time, and

activating the uninhibited GABA-a receptors through the action of the GABA-a agonist during the period of time; and

relaxing smooth muscle of the systemic blood vessels as a result of increased prostacyclin release. (emphasis added).

The applicant had conceded during prosecution that GABA-a agonists and ARBs had been known as essential hypertension treatments for many decades. The Examiner agreed and found that the claimed results (increased release of prostacyclin; activating the uninhibited GABA-a receptors; relaxing smooth muscle of the systemic blood vessels) were not patentable because they naturally flowed from the claimed administration of the known antihypertensive agents.

On appeal to the PTAB, the applicant asserted that the prostacyclin increase was unexpected and that objective indicia had overcome any existing prima facie case of obviousness. The PTAB affirmed the rejection, holding that the claimed result of an increased prostacyclin release was inherent, and that the objective indicia arguments did not overcome the rejection because no evidence existed to support a finding of objective indicium.

Discussion

The PTAB’s legal determination is reviewed de novo, and the factual findings are reviewed for substantial evidence.

Couvaras asserts that (1) the Board erred in affirming that motivation to combine the art applied by the Examiner, (2) that the claimed mechanism of action was unexpected in that the Board erred in discounting its patentable weight by deeming it inherent, and (3) that the Board erred in weighing objective indicia of nonobviousness.

1. Motivation to Combine

As explained by the Examiner and affirmed by the Board, “[i]t is prima facie obvious to combine two compositions each of which is taught by the prior art to be useful for the same purpose, in order to form a third composition which is to be used for the very same purpose.” Couvaras asserted that the Board’s reasoning was too generic. However, it is undisputed that the antihypertensive agents recited in the claims existed and were known to treat hypertension.

Couvaras also asserted that even if there had been a motivation to combine, such motivation would fail to identify a finite number of identified, predicted solutions. The CAFC dismissed this argument because (1) it was made in a footnote and thus waived, (2) there was no evidence presented regarding a “substantial number of hypertension treatment agent classes”, and (3) the Board’s conclusion was supported by substantial evidence.

Regarding a reasonable expectation of success, Couvaras did not present any arguments against the Examiner’s findings when the rejection was appealed.

2. Unexpected Mechanism of Action

Couvaras contends that because the increased prostacyclin release was unexpected, it cannot be dismissed as having no patentable weight due to inherency, citing Honeywell International Inc. v. Mexichem Amanco Holdings S.A.,865 F.3d 1348, 1355 (FED. Cir. 2017). This decision, however, held that unexpected properties may cause what may appear to be an obvious composition to be nonobvious, not that the unexpected mechanisms of action must be found to make the known use of known compounds nonobvious. As stated in the opinion:

We have previously held that “[n]ewly discovered results of known processes directed to the same purpose are not patentable because such results are inherent.” In re Montgomery, 677 F.3d 1375, 1381 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (citation omitted); see also In re Huai-Hung Kao, 639 F.3d 1057, 1070–71 (Fed. Cir. 2011) (holding that a “food effect” was obvious because the effect was an inherent property of the composition). While mechanisms of action may not always meet the most rigid standards for inherency, they are still simply results that naturally flow from the administration of a given compound or mixture of compounds. Reciting the mechanism for known compounds to yield a known result cannot overcome a prima facie case of obviousness, even if the nature of that mechanism is unexpected.”

3. Weighing objective indicia of nonobviousness

To establish unexpected results, Couvaras needed to show that the co-administration of a GABA-a agonist and an ARB provided an unexpected benefit, such as, e.g., better control of hypertension, less toxicity to patients, or the ability to use surprisingly low dosages. The CAFC agreed with the Board that no such benefits have been shown, and therefore no evidence of unexpected results exists.

Takeaways

- Evidence needs to be presented to rebut a prima facie rejection. It seems that the applicant was attempting to assert that the combined use of the 2 agents provided unexpected results (better than what would be expected) based on synergy. As set forth in MPEP 716.02, greater than expected results are evidence of nonobviousness.

MPEP 716.02(a)

Evidence of a greater than expected result may also be shown by demonstrating an effect which is greater than the sum of each of the effects taken separately (i.e., demonstrating “synergism”). Merck & Co. Inc. v. Biocraft Laboratories Inc., 874 F.2d 804, 10 USPQ2d 1843 (Fed. Cir.), cert. denied, 493 U.S. 975 (1989). However, a greater than additive effect is not necessarily sufficient to overcome a prima facie case of obviousness because such an effect can either be expected or unexpected. Applicants must further show that the results were greater than those which would have been expected from the prior art to an unobvious extent, and that the results are of a significant, practical advantage. Ex parte The NutraSweet Co., 19 USPQ2d 1586 (Bd. Pat. App. & Inter. 1991) (Evidence showing greater than additive sweetness resulting from the claimed mixture of saccharin and L-aspartyl-L-phenylalanine was not sufficient to outweigh the evidence of obviousness because the teachings of the prior art lead to a general expectation of greater than additive sweetening effects when using mixtures of synthetic sweeteners.).

It seems that no evidence was presented to support the applicant’s argument of synergy. In reviewing the prosecution history, there were two interviews with the primary Examiner, one of which also included the Supervisory Examiner (SPE)[1]. In the interview summary, the Examiners indicated that the claims were too broad in that there were no amounts recited, no dose regime and/or no specific agents recited. It seems that a successful outcome could have been possible if evidence had been presented which was commensurate in scope with the claims.

- Once an Examiner establishes a prima facie rejection, the burden shifts to the applicant to prove otherwise.

[1] It is never a good idea to call on the SPE to attend an interview with a Primary Examiner. This not only angers a Primary Examiner but also the SPE.

THE MORE YOU CLAIM, THE MORE YOU MUST ENABLE

Andrew Melick | July 12, 2023

Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi

Decided: May 18, 2023

Supreme Court of the United States. Opinion by Justice Gorsuch

Summary:

Amgen owns patents covering antibodies that help reduce levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. Amgen sued Sanofi for infringement of its patents in district court. Sanofi raised the defense of invalidity for lack of enablement because while Amgen provided amino acid sequences for 26 antibodies, the claims cover potentially millions more undisclosed antibodies. The district court granted a motion for JMOL for invalidity due to lack of enablement, the CAFC affirmed, and the Supreme Court affirmed.

Details:

Amgen’s patents are to PCSK9 inhibitors. PCSK9 is a naturally occurring protein that binds to and degrades LDL receptors. PCSK9 causes problems due to degradation of LDL receptors because LDL receptors extract LDL cholesterol from the bloodstream. A method used to inhibit PCSK9 is to create antibodies that bind to a particular region of PCSK9 referred to as the “sweet spot” which is a sequence of 15 amino acids out of PCSK9’s 692 total amino acids. An antibody that binds to the sweet spot can prevent PCSK9 from binding to and degrading LDL receptors. Amgen developed a drug named REPATHA and Sanofi developed a drug named PRALUENT, both of which provide a distinct antibody with its own unique amino acid sequence. In 2011, Amgen and Sanofi received patents covering the antibody used in their respective drugs.

The patents at issue are U.S. Patent Nos. 8,829,165 and 8,859,741 issued in 2014 which relate back to Amgen’s 2011 patent. These patents are different from the 2011 patents in that they claim the entire genus of antibodies that (1) “bind to specific amino acid residues on PCSK9,” and (2) “block PCSK9 from binding to LDL receptors.” The relevant claims are provided:

Claims of the ‘165 patent:

1. An isolated monoclonal antibody, wherein, when bound to PCSK9, the monoclonal antibody binds to at least one of the following residues: S153, I154, P155, R194, D238, A239, I369, S372, D374, C375, T377, C378, F379, V380, or S381 of SEQ ID NO:3, and wherein the monoclonal antibody blocks binding of PCSK9 to LDLR.

19. The isolated monoclonal antibody of claim 1 wherein the isolated monoclonal antibody binds to at least two of the following residues S153, I154, P155, R194, D238, A239, I369, S372, D374, C375, T377, C378, F379, V380, or S381 of PCSK9 listed in SEQ ID NO:3.

29. A pharmaceutical composition comprising an isolated monoclonal antibody, wherein the isolated monoclonal antibody binds to at least two of the following residues S153, I154, P155, R194, D238, A239, I369, S372, D374, C375, T377, C378, F379, V380, or S381 of PCSK9 listed in SEQ ID NO: 3 and blocks the binding of PCSK9 to LDLR by at least 80%.

Claims of the ‘741 patent:

1. An isolated monoclonal antibody that binds to PCSK9, wherein the isolated monoclonal antibody binds an epitope on PCSK9 comprising at least one of residues 237 or 238 of SEQ ID NO: 3, and wherein the monoclonal antibody blocks binding of PCSK9 to LDLR.

2. The isolated monoclonal antibody of claim 1, wherein the isolated monoclonal antibody is a neutralizing antibody.

7. The isolated monoclonal antibody of claim 2, wherein the epitope is a functional epitope.

In its application, Amgen identified the amino acid sequences of 26 antibodies that perform these two functions. Amgen provided two methods to make other antibodies that perform the described binding and blocking functions. Amgen refers to the first method as the “roadmap,” which provides instructions to:

(1) generate a range of antibodies in the lab; (2) test those antibodies to determine whether any bind to PCSK9; (3) test those antibodies that bind to PCSK9 to determine whether any bind to the sweet spot as described in the claims; and (4) test those antibodies that bind to the sweet spot as described in the claims to determine whether any block PCSK9 from binding to LDL receptors.

Amgen refers to the second method as “conservative substitution” which provides instructions to:

(1) start with an antibody known to perform the described functions; (2) replace select amino acids in the antibody with other amino acids known to have similar properties; and (3) test the resulting antibody to see if it also performs the described functions.

Amgen sued Sanofi for infringement of claims 19 and 29 of the ‘165 patent and claim 7 of the ‘741 patent. Sanofi raised the defense of invalidity because Amgen had not enabled a person skilled in the art to make and use all of the antibodies that perform the two functions Amgen described in the claims. Sanofi argued that Amgen’s claims cover potentially millions more undisclosed antibodies that perform the same two functions than the 26 antibodies identified in the patent.

The court provided an explanation of the law and policy regarding the enablement requirement. 35 U.S.C. § 112 requires that a specification include “a written description of the invention, and of the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art … to make and use the same.” The court stated:

the law secures for the public its benefit of the patent bargain by ensuring that, upon the expiration of [the patent], the knowledge of the invention [i]nures to the people, who are thus enabled without restriction to practice it.

The court stated that “the specification must enable the full scope of the invention as defined by its claims.” Specifically, the court stated:

If a patent claims an entire class of processes, machines, manufactures, or compositions of matter, the patent’s specification must enable a person skilled in the art to make and use the entire class.

The court emphasized that the enablement requirement does not always require a description of how to make and use every single embodiment within a claimed class. A few examples may suffice if the specification also provides “some general quality … running through” the class. A specification may also not be inadequate just because it leaves a skilled artisan to engage in some measure of adaptation or testing, i.e., a specification may call for a reasonable amount of experimentation to make and use a patented invention. “What is reasonable in any case will depend on the nature of the invention and the underlying art.”

Regarding this case, the court stated that while the 26 exemplary antibodies provided by Amgen are enabled by the specification, the claims are much broader than the specific 26 antibodies. And even allowing for a reasonable degree of experimentation, Amgen has failed to enable the full scope of the claims.

The court stated that Amgen seeks to monopolize an entire class of things defined by their function and that this class includes a vast number of antibodies in addition to the 26 that Amgen has described by their amino acid sequences. “[T]he more a party claims, the broader the monopoly it demands, the more it must enable.”

Amgen argued that the claims are enabled because scientists can make and use every undisclosed but functional antibody if they simply follow Amgen’s “roadmap” or its proposal for “conservative substitution.” The court stated that these instructions amount to two research assignments and that they leave scientists “forced to engage in painstaking experimentation to see what works.” The court referred to Amgent’s two methods as “a hunting license.”

Comments

The key takeaway from this case is that the broader your claims are, the more your specification must enable. If it is difficult to show enablement for every embodiment claimed, then make sure your specification describes some general quality throughout the class or genus. A reasonable amount of experimentation is permissible for enablement, but reasonableness will depend on the nature of the invention and the underlying art.

Joint Inventorship Gone Up In Smoke For Want of Significant Contribution

Fumika Ogawa | June 16, 2023

HIP, INC. v. HORMEL FOODS CORPORATION

Decided: May 2, 2023

Before Lourie, Clevenger, and Taranto. Opinion by Lourie.

Summary

The CAFC held that an alleged inventor did not make a contribution sufficiently significant in quality to establish joint inventorship to an issued patent, where the alleged contributed concept was only minimally mentioned throughout the entirety of the patent document including the specification, drawings and claims.

Details

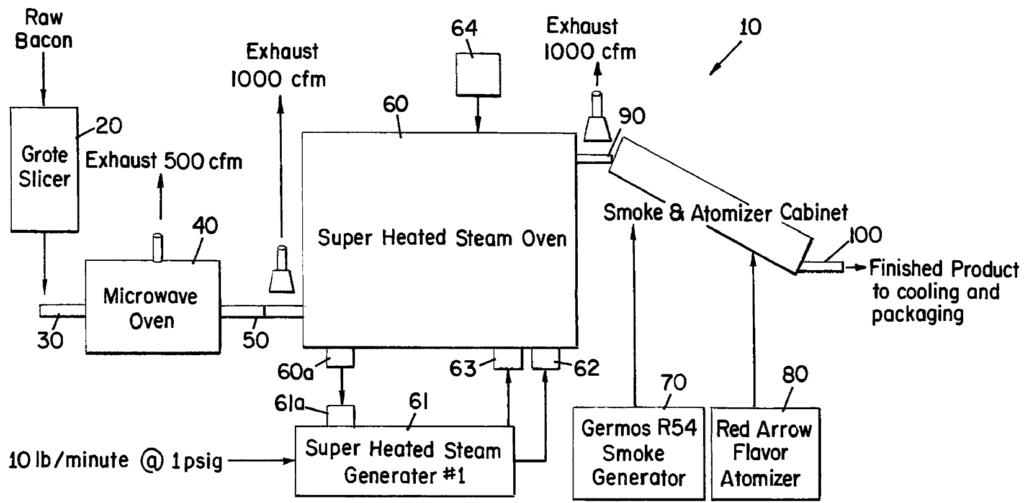

Hormel Foods Corporation (“Hormel”) owns U.S. Patent 9,980,498 (the “’498 patent”) relating to production of precooked bacon. While a traditional bacon producer would “precook” or prepare the bacon prior to sale by a certain type of oven, such as microwave or steam oven, the invention uses a two-step, hybrid oven system to improve the precooking process. FIG. 1, reproduced below, depicts a principle embodiment where a microwave oven 40 initially heats bacon so as to form a coating of melted fat around the meat piece, followed by a super heated steam oven 60 equipped with external steam source 61 for further cooking to a finishing temperature:

Per the ‘498 patent, the first step of forming the “fat barrier” protects the underlying meat from condensation and resulting dilution of flavor, whereas the second step using the external gas source prevents the oven’s internal surfaces from becoming hotter than the smoke point of bacon fat, which would otherwise cause off flavor of the resulting product.

The ’498 patent includes independent claims 1, 5 and 13, defining the inventive method using slightly different languages from each other. As relevant on appeal, claims 1 and 13 both recite a particular mode of cooking in the first step of the hybrid system as “preheating … with a microwave oven,” whereas claim 5 recites three alternative preheating techniques using a Markush language, “selected from the group consisting of a microwave oven, an infrared oven, and hot air.”

As part of its R&D efforts toward the improved precooking process, Hormel contacted Unitherm Food Systems, Inc. (“Unitherm”), now HIP, a manufacturer of cooking machinery such as industrial ovens. The parties jointly agreed to develop an oven to be used in a two-step cooking process. The alleged inventor in question, David Howard of Unitherm, was involved in those meetings and testing process where he allegedly disclosed an infrared heating concept to Hormel. As Hormel’s further R&D—including testing with their own facility instead of Unitherm’s facility—eventually led to the discovery of the inventive two-step process, Hormel filed for a patent. The resulting ’498 patent named four inventors, which did not include Howard.

HIP sued Hormel in the District Court for the District of Delaware, alleging that Howard was either the sole inventor or a joint inventor of the ’498 patent. HIP argued, among other things, that Howard contributed to preheating with an infrared oven, the concept recited in independent claim 5. The district court held that although Howard was not the sole inventor, his contribution of the infrared oven concept made him a joint inventor of the ’498 patent. Hormel appealed.

On appeal, Hormel argued, among other things,[1] that Howard was not a joint inventor because the infrared oven concept was well known, and his alleged contribution was insignificant in quality relative to the extent of the full invention.

Specifically, the joint inventorship issue was argued based on the three-part test set forth in Pannu v. Iolab Corp., 155 F.3d 1344, 1351. Under Pannu, to qualify as an additional joint inventor, one must have:

(1) contributed in some significant manner to the conception of the invention;

(2) made a contribution to the claimed invention that is not insignificant in quality, when that contribution is measured against the dimension of the full invention; and

(3) did more than merely explain to the real inventors well-known concepts and/or the current state of the art.

Hormel asserted that Howard met none of the three factors, and HIP countered that each and every factor was met so as to establish joint inventorship.

The CAFC ultimately sided with Hormel. The CAFC focused its analysis on the second Pannu factor, noting specific circumstances:

- Small # of times mentioned in the specification: The alleged contribution, preheating with an infrared oven, is “mentioned only once in the … specification as an alternative heating method to a microwave oven.”

- Small # of times mentioned in the claims: The alleged contribution is “recited only once in a single claim” whereas the two other independent claims recite preheating with a microwave oven, with no mention of an infrared oven.

- Presence of a more significant alternative in the disclosure: The alternative to the alleged contribution, preheating with a microwave oven, “feature[s] prominently throughout the specification, claims, and figures.”

- Specification focused on the alternative: All the specific examples disclosed in the specification are limited to embodiments using preheating with a microwave oven.

- Drawings focused on the alternative: All the figures, including Figure 1 primarily depicting the operating principles of the claimed invention, are limited to embodiments based on preheating with a microwave oven.

Noting that the entirety of the ’498 patent disclosure supports insignificance in quality of the alleged contribution per the second part of Pannu test, the CAFC concluded that Howard did not qualify as a joint inventor. Lastly, the CAFC noted that there was no need to address the other Pannu factors “as the failure to meet any one factor is dispositive on the question of inventorship.”

Takeaway

This case provides a reminder of the role a patent disclosure may play in determining the question of joint inventorship. In particular, although the second Pannu factor requires the inventor’s contribution to be “not insignificant in quality” (emphasis added), in certain circumstances, the amount of mentions made of the alleged contributed concept in the patent, along with other considerations such as the primary focus of the patent as discerned from the entire disclosure, may influence the determination of joint inventorship.

[1] Hormel’s second main argument challenges insufficiency of corroboration of Howard’s testimony, the question rendered moot due to the decision on the significance of the alleged contribution.

CAFC upheld ITC’s ruling under the ‘Infrequently Applied’ Anderson two-step test regarding the enablement of open-ended ranges

Adele Critchley | June 8, 2023

FS.com Inc. v. ITC and Corning Optical Corp.

Decided: April 20, 2023

Before Moore, Prost and Hughes. Opinion by Moore.

Summary:

Corning filed a complaint with the ITC alleging FS was violating §337 of the Tariff Act of 1930, as amended (19 U.S.C. 1337), (a.k.a ‘unfair import’) by importing high-density fiber optic equipment that infringed several of their patents – U.S. Patent Nos. 9,020,320; 10,444,456; 10,120,153; and 8,712,206. The patents relate to fiber optic technology commonly used in data centers.

The Commission ultimately determined that FS’ importation of the high-density fiber optic equipment violated §337 and issued a general exclusion order prohibiting the importation of infringing high-density fiber optic equipment and components thereof and a cease-and-desist order directed to FS.

Subsequently, FS appealed the Commission’s determination that the claims of the ’320 and ’456 patents are enabled and its claim construction of “a front opening” in the ’206 patent.

ISSUE 1: ENABLEMENT

FS challenges the Commission’s determination that claims 1 and 3 of the ’320 patent and claims 11, 12, 15, 16, and 21 of the ’456 patent are enabled. These claims recite, in part, “a fiber optic connection density of at least ninety-eight (98) fiber optic connections per U space” or “a fiber optic connection of at least one hundred forty-four (144) fiber optic connections per U space.” FS argued these open-ended density ranges are not enabled because the specification only enables up to 144 fiber optic connections per U space.

A patent’s specification must describe the invention and “the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art to which it pertains . . . to make and use the same.” 35 U.S.C. § 112(a). To enable, “the specification of a patent must teach those skilled in the art how to make and use the full scope of the claimed invention without undue experimentation.”

In determining enablement, the Commission applied the two-part standard set forth in Anderson Corp. v. Fiber Composites, LLC, 474 F.3d 1361 (Fed. Cir. 2007):

[O]pen-ended claims are not inherently improper; as for all claims their appropriateness depends on the particular facts of the invention, the disclosure, and the prior art. They may be supported if there is an inherent, albeit not precisely known, upper limit and the specification enables one of skill in the art to approach that limit.

Although the CAFC acknowledged that the Anderson test is infrequently applied, both FS and Corning agreed that the test governed their legal dispute. In applying this standard, the Commission determined the challenged claims were enabled because skilled artisans would understand the claims to have an inherent upper limit and that the specification enables skilled artisans to approach that limit.

The CAFC agreed, understanding the Commission’s opinion as determining there is an inherent upper limit of about 144 connections per U space. See Appellant’s Opening Br. at 51 (“The only potential finding by the Commission of an inherent upper limit to the open-ended claims is approximately 144 connections per 1U space.”). Specifically, that determination was based on the Commission’s finding that skilled artisans would have understood, as of the ’320 and ’456 patent’s shared priority date (August 2008), that densities substantially above 144 connections per U space were technologically infeasible. This was supported by expert testimony.

ISSUE 2: CLAIM CONSTRUCTION

The Commission construed “a front opening” in claim 14 of the ’206 patent as encompassing one or more openings. FS argued the proper construction of “a front opening” is limited to a single front opening and therefore its modules, which contain multiple openings separated by material or dividers, do not infringe claims 22 and 23. The CAFC disagreed.

The CAFC held that, generally, the terms “a” or “an” in a patent claim mean “one or more,” unless the patentee evinces a clear intent to limit “a” or “an” to “one.” 01 Communique Lab’y, Inc. v. LogMeIn, Inc., 687 F.3d 1292, 1297 (Fed. Cir. 2012). The CAFC concluded here that the claim language and written description did not demonstrate a clear intent to depart from this general rule.

Comments:

- Open-end ranges are not automatically improper. If such a range is required/desired during prosecution, apply the two-part standard set forth in Anderson: (1) is there inherent, albeit not precisely known, support for an upper limit and (2) does the specification enables one of skill in the art to approach that limit.

- The terms “a” or “an” in a patent claim remain to mean “one or more,” unless the patentee evinces a clear intent to limit “a” or “an” to “one.”