Depends On How You Slice It: CAFC reverses PTAB on Weber v. Provisur IPR ruling

Michael Caridi | April 5, 2024

Weber, Inc. v. Provisur Tech. Inc.

Decided: February 8, 2024

Before Reyna, Hughes and Stark. Authored by Reyna

Summary: The Court reversed the PTAB’s finding that Weber’s instruction manuals did not qualify as printed publications under 35 USC §102. The Court also reversed key claim construction taken by the PTAB in upholding Provisur’s patents.

Background:

Provisur sued Weber for patent infringement on two patents, USP 10,639,812 (“’812 patent”) and 10,625,436 (“’436 patent”) relate to high-speed mechanical slicers used in food-processing plants. Weber countered by filing IPR proceedings against both patents at the USPTO Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). The PTAB found both the ‘812 and the ‘436 patentable. During the PTAB proceeding, Weber had attempted to use their own instruction manual for the slicer they sold as a prior art publication under 35 U.S.C. §102. The Board found that the instruction manual was not a “printed publication” under §102 on the basis that the manuals were controlled in their circulation to only customers or potential customers by a strict copyright and confidentiality clause.

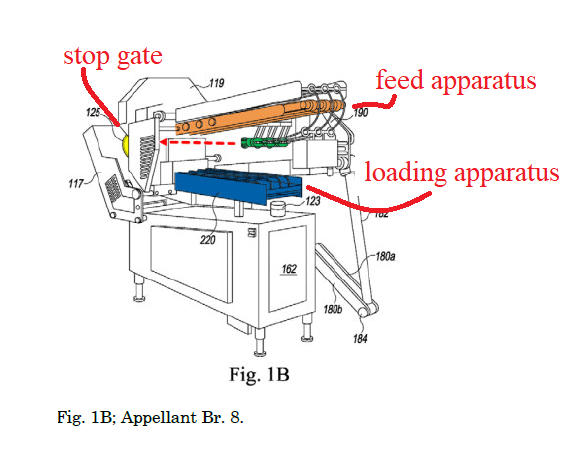

Further, the PTAB had construed three terms from the slicer components, (1) the “food article loading apparatus”; (2) the “food article feed apparatus”; and (3) the “food article stop gate” in a manner that maintained the patents’ validity while excluding the disclosures in Weber’s manuals.

Weber appealed the Board’s finding that their instruction manual was not a printed publication under §102 and the claim construction of the three terms.

Decision:

(a) Weber’s Instruction Manual as a “Printed Publication”

The Board had relied upon the CAFC’s prior holding in Cordis Corp. v. Boston Scientific Corp., 561 F.3d 1319 (Fed. Cir. 2009), in finding that Weber’s manuals were not “printed publications.” In Cordis, the references in question were two academic monographs describing an inventor’s work that were only distributed to a handful colleagues and two companies potentially interested in the technology.

The CAFC was quick to distinguish the current case from Cordis. First, the CAFC noted that the statutory phrase “printed publication” from § 102 has been defined to mean a reference that was “sufficiently accessible to the public interested in the art,” citing In re Klopfenstein, 380 F.3d 1345, 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2004) and that “public accessibility” was based on the relevant public being able to “locate the reference by reasonable diligence,” citing Valve Corp. v. Ironburg Inventions Ltd., 8 F.4th 1364, 1376 (Fed. Cir. 2021). Next, the Court found that Weber’s operating manuals were created for dissemination to the interested public to provide instructions for Weber’s slicer. The Court stated the Weber manuals were in “stark contrast” to the confidential monographs in Cordis which were subject to “academic confidentiality norms.” The Court went on to describe that the evidence provided by employees of Weber, stating that the manuals were readily provided to potential buyers, clearly indicated that the manuals did in fact qualify as “printed publications” under §102.

The Court also found the Board’s reliance on the copyright and confidentiality of Weber’s manuals to be misplaced. The Board had keyed in on the copyright language restricting the reproduction or transfer of the manuals and Weber’s “terms and conditions” stating that documents related to a sale of a slicer “remain the property of” Weber. The CAFC was not convinced that these statements made the manuals confidential to the point of not being a “printed publication”, stating:

Weber’s assertion of copyright ownership does not negate its own ability to make the reference publicly accessible. Cf. Correge v. Murphy, 705 F.2d 1326, 1328–30 (Fed. Cir. 1983) (“A mere assertion of ownership cannot convert what was in fact a public disclosure and offer to sell to numerous potential customers into a non-disclosure.”). The intellectual property rights clause from Weber’s terms and conditions covering sales, likewise, has no dispositive bearing on Weber’s public dissemination of operating manuals to owners after a sale has been consummated.

The Court reversed the PTAB’s finding that Weber’s instruction manuals were not “printed publications” within the meaning of 35 U.S.C. §102.

(b) Claim Construction – “disposed over” and “stop gate”

The Court next addressed the PTAB’s claim construction as to the term “disposed over” as used in the claims. The Board had construed the term “disposed over” to require that the “feed apparatus and its conveyor belts and grippers are ‘positioned above and in vertical and lateral alignment with’ the food article loading apparatus and its lift tray assembly.” The Court rejected this interpretation asserting that it reads elements into the claim which are not present. The Court noted that the specification and prosecution history did not impart any limited meaning to the term “disposed over” and therefore there was no basis for including the additional aspect that the feed apparatus and loading apparatus were in alignment. Citing Cyntec Co. v. Chilisin Elecs. Corp., 84 F.4th 979, 986 (Fed. Cir. 2023), the Court held that “Had the patent drafter intended to limit the claims” to address the alignment of the conveyor belts and lift tray assembly between the apparatuses, “narrower language could have been used in the claim.”

Running Provisur through the figurative slicer, the Court noted that Provisur did not dispute that Weber’s manuals satisfy the limitation under Weber’s proposed construction (i.e. that alignment is not required between the feed and loading apparatus). Hence, they concluded that their review of the Board’s claim construction is dispositive of the issue and that the Weber manuals do disclose the “disposed over” limitation.

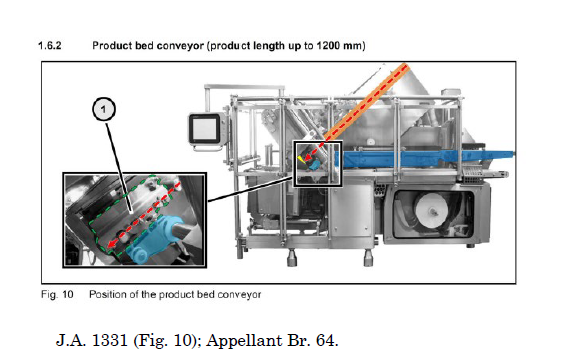

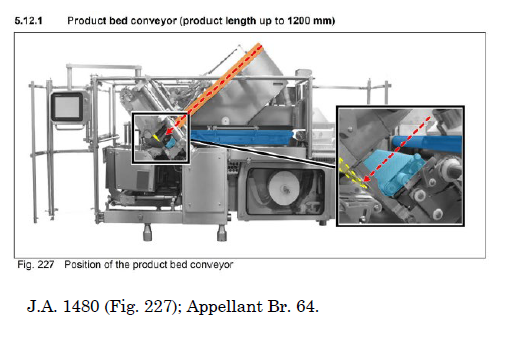

As to the “stop gate” term in the claims, Weber asserted that the Board erred in determining that the “product bed conveyer” disclosed in Weber’s operating manuals (as shown in Figures 10 and 227 thereof), does not disclose the “stop gate” limitation.

After analyzing the figures, the Court only commented that given these disclosures of the Weber manuals there was no substantial evidentiary support for the Board’s finding. Thus, the Court again reversed on the “stop gate” determinations.

Take aways:

- The Court clarifies the meaning of “printed publication” in 35 U.S.C. §102 by further defining the line between documents primarily intended to be confidential, such as the monographs in Cordis, and those primarily intended to be disseminated to the interested public, such as Weber’s manuals.

- By reversing the PTAB’s claim interpretation that had read a required alignment of parts into the claim where no such requirement was present, the Court also reiterates the standing law of claim construction that claim terms have their ordinary meaning unless intrinsic evidence demonstrates otherwise.

THE DOMESTIC INDUSTRY REQUIREMENT FOR AN ITC COMPLAINT CAN BE SATISFIED BASED ON A SUBSET OF A PRODUCT IF THE IP INVOLVES ONLY THAT SUBSET

WHDA CAFC Alert | March 22, 2024

Roku, Inc. v. ITC

Decided: January 19, 2024

Before Dyk, Hughes, and Stoll. Opinion by Hughes.

Summary:

Universal Electronics, Inc. (“Universal”) filed a complaint against Roku in the International Trade Commission (ITC) for importing certain TV products that infringe U.S. Patent No. 10,593,196. The issues on appeal include whether the final determination of the ITC is proper in finding that (1) Universal had ownership rights to assert the ‘196 patent in the complaint; (2) Universal satisfied the economic prong of the domestic industry requirement under 19 U.S.C. § 1337(a)(3)(C) to bring a complaint at the ITC; and (3) Roku failed to demonstrate that the ‘196 patent was obvious over the prior art. The CAFC affirmed the ITC’s findings.

Details:

The ‘196 patent is to a device for allowing communication between various devices such as smart TVs and DVD players that may use different communication protocols such as wired connections (e.g., HDMI) or wireless communication (Wi-Fi or Bluetooth) that may be incompatible with each other. The ‘196 patent discloses a universal control engine (referred to as a “first media device” in the claims) that can scan various target devices (referred to as “second media devices” in the claims). The first media device receives wireless signals from various devices such as a remote control or an app on a tablet computer and can transmit commands using wired or IR signals to controllable devices such as TVs, DVRs or a DVD player.

Claim 1 is provided:

1. [pre] A first media device, comprising:

[a] a processing device;

[b] a high-definition multimedia interface communications port, coupled to the processing device, for communicatively connecting the first media device to a second media device;

[c] a transmitter, coupled to the processing device, for communicatively coupling the first media device to a remote control device; and

[d] a memory device, coupled to the processing device, having stored thereon processor executable instruction;

[e] wherein the instructions, when executed by the processing device,

[i] cause the first media device to be configured to transmit a first command directly to the second media device, via use of the high-definition multimedia communications port, to control an operational function of the second media device when a first data provided to the first media device indicates that the second media device will be responsive to the first command, and

[ii] cause the first media device to be configured to transmit a second data to a remote control device, via use of the transmitter, for use in configuring the remote control device to transmit a second command directly to the second media device, via use of a communicative connection between the remote control device and the second media device, to control the operational function of the second media device when the first data provided to the first media device indicates that the second media device will be unresponsive to the first command.

1. Ownership Issue

After filing its complaint, Universal filed a petition for correction of inventorship to add an inventor (Mr. Barnett) to the patent. Roku had filed a motion for summary determination before the ALJ that Universal lacked standing to assert the ‘196 patent because at the time Universal filed its complaint, it did not own all rights to the ‘196 patent. Roku argued that a 2004 agreement between Mr. Barnett and Universal did not constitute an assignment of rights.

The ALJ agreed stating that the 2004 agreement was a “mere promise to assign rights in the future, not an immediate transfer of expectant rights,” and thus, the 2004 agreement “did not automatically assign any of Mr. Barnett’s rights to the Provisional Applications of the ‘196 patent that eventually issued from the priority chain.”

The Commission reversed stating that there was a separate agreement in 2012 in which Mr. Barnett assigned all his rights to a series of provisional applications including the provisional which led to the ‘196 patent. The language of the assignment states that Mr. Barnett “hereby sell[s] and assign[s] … [his] entire right, title, and interest in and to the invention,” including “all divisions and continuations thereof, including the subject-matter of any and all claims which may be obtained in every such patent.” The Commission further found that Mr. Barnett did not contribute any new or inventive matter to the ‘196 patent after filing the provisional applications. The Commission found that the 2012 agreement constituted a “present conveyance” of Mr. Barnett’s rights in the ‘196 patent. The CAFC agreed with the Commission that the agreement constitutes a “present conveyance,” and thus, Universal had ownership rights to assert the ‘196 patent.

2. Domestic Industry Requirement – Economic Prong

To bring complaint at the ITC under Section 337, the complainant must possess a domestic industry in the United States. Domestic industry can be satisfied by showing “substantial investment in [a patent’s] exploitation, including engineering, research and development, or licensing.” 19 U.S.C. § 1337(a)(3)(C).

The Commission found that Universal had substantial investments in domestic engineering and R&D related to a platform called QuickSet which is incorporated into multiple smart TVs. The Commission found that the QuickSet platform involves software and software updates that result in practice of the asserted claims when implemented on the Samsung DI products and that Universal’s asserted expenditures are attributable to its domestic investments in R&D and engineering. The Commission further found that Universal’s investments go directly to the functionality necessary to practice many claimed elements of the ‘196 patent. The CAFC held that the Commission’s findings are supported by substantial evidence.

Roku attempted to frame the argument with regard to the TV as a whole rather than the QuickSet technology that is installed on those TVs to argue that Universal has not satisfied the domestic industry requirement. However, the CAFC stated that the domestic industry requirement “does not require expenditures in whole products themselves, but rather, sufficiently substantial investment in the exploitation of the intellectual property.” The CAFC further stated “a complainant can satisfy the economic prong of the domestic industry requirement based on expenditures related to a subset of a product, if the patent(s) at issue only involve that subset.” The CAFC held that the IP at issue in this case is practiced by QuickSet and the related QuickSet technologies, which is a subset of the entire TV.

3. Obviousness

Roku argued obviousness of the claims based on prior art references Chardon and Mishra. The parties agreed that Chardon disclosed all of the limitations of claim 1 except for limitation 1[e][ii]. Roku cited Mishra for teaching this feature. The ALJ found that Universal had presented evidence of secondary considerations showing that QuickSet satisfied a long-felt but unmet need that outweighed Roku’s obviousness case. The Commission went further regarding non-obviousness finding that the combination of Chardon and Mishra does not disclose a system that automatically configures two different control devices to transmit commands over different pathways. The Commission further found that Roku failed to present clear and convincing evidence of a motivation to combine the references.

On appeal, Roku merely argued that the Commission erred by accepting Universal’s evidence of secondary considerations. Roku argued that the Commission erred in finding a nexus between the secondary considerations of non-obviousness and the claims because some of the news articles presented by Universal discuss features in addition to QuickSet. The CAFC held that this argument is meritless because Roku did not dispute that QuickSet is discussed in the references that the Commission relied on.

The CAFC further stated that Roku did not challenge the actual findings that the combination of Chardon and Mishra does not disclose limitation 1[e], i.e., allowing for a choice between different second media devices. Thus, the Commission’s obviousness determination was affirmed.

Comments

When filing a patent infringement suit, make sure inventorship and ownership are clear, and make any necessary corrections before filing suit. When filing a complaint at the ITC, keep in mind that the domestic industry requirement does not require showing expenditures on whole products if the patent at issue only involves a subset of the product.

Inventor declaration not related to what is claimed or discussed in the patent would not help the patent to survive from patent eligibility attack in the pleading stage

Sung-Hoon Kim | March 8, 2024

INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MACHINES CORPORATION v. ZILLOW GROUP, INC., ZILLOW, INC.

Decided: January 9, 2024

Hughes (author), Prost, and Stoll

Summary:

The Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision holding that the claims of two IBM’s patents are directed to patent ineligible subject matter under §101, and properly granting Zillow’s motion to dismiss under FRCP 12(b)(6).

Details:

IBM appealed a decision from the Western District of Washington, where the district court granted Zillow’s motion to dismiss under FRCP 12(b)(6). The district court held that all patent claims asserted against Zillow by IBM were directed to ineligible subject matter under 35 U.S.C. §101.

At issue in this appeal were IBM’s two patents – U.S. Patent Nos. 6,778,193 and 6,785,676.

The ’193 patent

The ’193 patent is directed to a “graphical user interface for a customer self-service system that performs resource search and selection.”

This patent is directed to improving how search results are displayed to a user by providing three visual workspaces: (1) a user begins by entering their search query into a “Context Selection Workspace”; (2) a user can further specify the details of their search in a “Detail Specification Workspace”; and (3) a user can view the results of their search in a “Results Display Workspace.”

Independent claim 1 is a representative claim:

1. A graphical user interface for a customer self service system that performs resource search and selection comprising:

a first visual workspace comprising entry field enabling entry of a query for a resource and, one or more selectable graphical user context elements, each element representing a context associated with the current user state and having context attributes and attribute values associated therewith;

a second visual workspace for visualizing the set of resources that the customer self service system has determined to match the user’s query, said system indicating a degree of fit of said determined resources with said query;

a third visual workspace for enabling said user to select and modify context attribute values to enable increased specificity and accuracy of a query’s search parameters, said third visual workspace further enabling said user to specify resource selection parameters and relevant resource evaluation criteria utilized by a search mechanism in said system, said degree of fit indication based on said user’s context, and said associated resource selection parameters and relevant resource evaluation criteria; and,

a mechanism enabling said user to navigate among said first, second and third visual workspaces to thereby identify and improve selection logic and response sets fitted to said query.

The ’676 patent

The ’676 patent is directed to enhancing how search results are displayed to users by disclosing a four-step process of annotating resource results obtained in a customer self service system that performs resource search and selection.”

Independent claim 14 is a representative claim:

14. A method for annotating resource results obtained in a customer self service system that performs resource search and selection, said method comprising the steps of:

a) receiving a resource response set of results obtained in response to a current user query;

b) receiving a user context vector associated with said current user query, said user context vector comprising data associating an interaction state with said user and including context that is a function of the user;

c) applying an ordering and annotation function for mapping the user context vector with the resource response set to generate an annotated response set having one or more annotations; and,

d) controlling the presentation of the resource response set to the user according to said annotations, wherein the ordering and annotation function is executed interactively at the time of each user query.

The District Court

Initially, IBM sued Zillow in the Western District of Washington for allegedly infringing five patents. The claims for two patents were dismissed, and Zillow filed a motion to dismiss under FRCP 12(b)(6) for the remaining three patents.

As for the ’676 patent, the district court found that the claims were merely directed to offering a user ‘the most beneficial and meaningful way’ to view the results of a query… and not advancing computer capabilities per se.”

The district court noted that four steps could be performed with a pen and paper, and that the claims were merely result-oriented.

Therefore, the district court found the asserted claims of the ’676 patent ineligible under §101.

As for the ’193 patent, the district court found that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of “more precisely tailoring the outcome of a query by guiding users (via icons, pull-down menus, dialogue boxes, and the like) to make choices about specific context variables, rather than requiring them to formulate and enter detailed search criteria.”

The district court did not find user context icons, separate workstations, and iterative navigation to be inventive concepts and held that they were well-understood, routine, or conventional at the time of the invention.

Therefore, the district court similarly found the asserted claims of the ’193 patent ineligible under §101.

The CAFC

The CAFC reviewed de novo.

As for the ’193 patent, the CAFC agreed with the district court that the claims do nothing more than improving a user’s experience while using a computer application.

Here, the CAFC noted that IBM failed to explain how the claims do anything more than identify, analyze, and present certain data to a user and that the claims did not disclose any technical improvement to how computer applications are used.

Furthermore, the CAFC agreed with the district court that IBM’s allegations of inventiveness “do[] not . . . concern the computer’s or graphical user interface’s capability or functionality, [but] relate[] merely to the user’s experience and satisfaction with the search process and results.”

Finally, the CAFC noted that the inventor declaration (“one of the key innovative aspects of the invention of the ’193 patent was not just the multiple visual workspaces alone, but how these various visual workspaces build upon each other and interact with each other,” as well as “the use of one visual workspace to affect the others in a closed-loop feedback system.”) did not cite the patent at all, and that neither the claims nor the specification include any such information. Therefore, the CAFC held that simply including allegations of inventiveness in a complaint with the inventor declaration did not make the complaint survive at the pleading stage.

Accordingly, the CAFC affirmed the district court’s decision holding that the ’193 patent is directed to ineligible subject matter under §101 and granting Zillow’s motion to dismiss as to the ’193 patent.

As for the ’676 patent, the CAFC agreed with the district court that the claims are directed to an abstract idea of displaying and organizing information because the representative claims use results-oriented language without mentioning any specific mechanism to perform the claimed steps.

In addition, the CAFC agreed with the district court that IBM failed to plausibly allege any inventive concept that would render the abstract claims patent-eligible.

IBM argued that the district court erred by failing to consider a supposed claim construction dispute regarding the term “user context vector”.

However, the CAFC noted that Zillow adapted IBM’s construction and did not propose an alternate construction. Therefore, the CAFC found that there was no claim construction dispute for the district court to resolve.

Accordingly, the CAFC affirmed the district court’s decision holding that the ’676 patent claimed ineligible subject matter under §101 and granting Zillow’s motion to dismiss as to the ’676 patent.

Dissenting opinion by Stoll

Stoll would vacate the district court’s holding of ineligibility of the claims of the ’676 patent because the majority, like the district court, did not meaningfully address IBM’s proposed construction of “user context vector.”

Takeaway:

- Conclusionary allegations of inventiveness in the inventor declaration would not help the patent to survive from patent eligibility attack in the pleading stage.

- The inventor declaration should be closely tied to the claims and the specification to help the patent to survive from patent eligibility attack.

Tags: 35 U.S.C. § 101 > declaration > Motion to Dismiss > patent eligible subject matter

The Twists and Turns of Claim Construction Issues in an IPR

John Kong | February 2, 2024

Parkervision v. Vidal

Decided: December 20, 2023

Summary:

Although patent owner ParkerVision’s claim construction was adopted in multiple district court litigations, it was not adopted by the PTAB in the IPR of the same patent. The Federal Circuit, reviewing claim construction de novo, affirmed the Board’s final decision. ParkerVision introduced the claim construction issue in its patent owner response, arguing that the claimed “storage element” should be construed as “an element of an energy transfer system that stores non-negligible amounts of energy from an input EM signal” and that the cited prior art did not teach the claimed “storage element” because its allegedly corresponding capacitors were not part of any energy transfer system. Intel filed a reply asserting that the interpretation of a “storage element” does not require it to be part of an energy transfer system. The Board and the Federal Circuit agreed. ParkerVision did not further argue in its patent owner response that the cited prior art’s capacitors failed the requirement that it store “non-negligible” amounts of energy from the input EM signal. ParkerVision included in its sur-reply that the cited prior art’s capacitors stored only a negligible amount of energy because “non-negligible” must be measured relative to the available energy of the input EM signal. The Board granted Intel’s motion to strike this part of ParkerVision’s sur-reply. The court affirmed, noting that there was no abuse of discretion when the Board refused to consider a new theory of patentability raised for the first time in a sur-reply.

Procedural History:

Intel petitioned for inter partes review (IPR) of claim 3 of Parkervision’s USP 7,110,444 (the ‘444 patent). There are related district court litigations involving the ‘444 patent and other related patents, which adopted a claim construction of a “storage element” aligned with Parkervision’s proposed claim construction. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (the Board) adopted Intel’s claim construction of a “storage element” and issued a final decision that the ‘444 patent was obvious over cited prior art. Parkervision appealed. In issuing its final decision, the Board recognized that several district court cases involving the ‘444 patent adopted claim constructions inconsistent with Intel’s proposed construction. See, ParkerVision, Inc. v. Intel Corp., Nos. 6:20-cv-108-ADA, 6:20-cv-562-ADA (W.D. Tex.); ParkerVision, Inc. v. Hisense Co., Nos. 6:20-cv-870-ADA, 6:21-cv-562-ADA (W.D. Tex.); ParkerVision, Inc. v. TCL Indus. Holdings Co., No. 6:20-cv-945-ADA (W.D. Tex.); ParkerVision, Inc. v. LG Elecs. Inc., No. 6:21-cv-520-ADA (W.D. Tex.).

Decision:

Claim 3 of the ‘444 patent is as follows:

A wireless modem apparatus, comprising:

a receiver for frequency down-converting an input signal including,

a first frequency down-conversion module to down-convert the input signal, wherein said first frequency down-conversion module down-converts said input signal according to a first control signal and outputs a first down-converted signal;

a second frequency down-conversion module to down-convert said input signal, wherein said second frequency down-conversion module down-converts said input signal according to a second control signal and outputs a second down-converted signal; and

a subtractor module that subtracts said second down-converted signal from said first down-con-verted signal and outputs a down-converted signal;

wherein said first and said second frequency down-conversion modules each comprise a switch and a storage element.

The ‘444 patent relates to wireless local area networks (WLANs) that use frequency translation technology. In a two-device network using frequency translation, the first device receives a low-frequency baseband signal (audible voice signal) and up-converts it to a high-frequency electromagnetic (EM) signal before wireless transmission to the second device. The second device receives the EM signal, down-converts it back to a low-frequency baseband signal, and outputs an audible signal. The ‘444 patent is directed to down-converting EM signals using down-converter modules that include a switch and a storage element (also called a storage module).

The main issue in this case is the claim construction for a “storage element.”

ParkerVision contends that a “storage element” is an element of an energy transfer system that stores non-negligible amounts of energy from an input EM signal. A magistrate judge’s claim construction order in ParkerVision v. LG and a special master’s recommendation in ParkerVision v. Hisense and in ParkerVision v. TCL adopted ParkerVision’s proposed claim construction.

Intel contends that a “storage element” is “an element of a system that stores non-negligible amounts of energy from an input EM signal” – which does not require that the element be part of an energy transfer system. The Board adopted Intel’s claim construction. The Federal Circuit agreed. This is dispositive in the obviousness holding because ParkerVision’s patent owner response in the IPR focused exclusively on the prior art’s lack of an energy transfer system.

The ‘444 patent incorporated by reference USP 6,061,551 (the ‘551 patent) which provided the following disclosure critical to the meaning of a “storage element”:

1 FIG. 82A illustrates an exemplary energy transfer system 8202 for down-converting an input EM signal 8204. 2 The energy transfer system 8202 includes a switching module 8206 and a storage module illustrated as a storage capacitance 8208. 3 The terms storage module and storage capacitance, as used herein, are distinguishable from the terms holding module and holding capacitance, respectively. 4 Holding modules and holding capacitances, as used above, identify systems that store negligible amounts of energy from an under-sampled input EM signal with the intent of “holding” a voltage value. 5 Storage modules and storage capacitances, on the other hand, refer to systems that store non-negligible amounts of energy from an input EM signal.

(bracketed numbers identifying referenced sentences)

This is deemed “lexicographic” because “as used herein” in sentence #3 refers to the use of these terms (contained throughout the drawings and specification) in general, and not to specific embodiments, and “refer to” in sentence #5 links “storage modules” (parties agreed this is synonymous with “storage element”) to “systems that store non-negligible amounts of energy from an input EM signal.”

ParkerVision’s argued that the ‘551 paragraph was addressing examples in which storage modules are used in energy transfer systems in which holding modules, by contrast, are used in under-sampling systems. The court dismissed this because the comparative nature of the paragraph does not prevent it from being definitional. And, the court refused to incorporate an entire “energy transfer system” into the claim just because a single component (storage element) can be a part of such a system. The court also stated that the district court claim constructions by the magistrate judge and special masters do not alter its conclusion that the Board arrived at the correct construction.

Another, procedural, issue on appeal is whether (1) the Board erred in relying on Intel’s reply (raising this claim construction issue that “storage element” is not limited to being part of an “energy transfer system”) and (2) the Board erred in striking parts of ParkerVision’s sur-reply.

First, ParkerVision asserted that the Board erred in relying on Intel’s arguments allegedly raised for the first time in Intel’s reply. The presumed contention is that the Board deprived ParkerVision of its procedural rights under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) and failed to comply with the USPTO’s rule that a reply “may only respond to arguments raised in the … patent owner response…” 37 C.F.R. § 42.23(b). The court reviews the Board’s compliance with the APA de novo, and the Board’s determination that a party violated USPTO rules for abuse of discretion. Under the APA, the Board must:

“timely inform[]” the patent owner of “the matters of fact and law asserted,” 5 U.S.C. § 554(b)(3), must provide “all interested parties opportunity for the submission and consideration of facts [and] arguments . . . [and] hearing and decision on notice,” id. § 554(c), and must allow “a party . . . to submit rebuttal evidence . . . as may be required for a full and true disclosure of the facts,” id. § 556(d).

Dell Inc. v. Acceleron, LLC, 818 F.3d 1293, 1301 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

Neither petitioner nor patent owner expressly proposed any pre-institution claim construction. Post-institution, ParkerVision first proposed a new claim construction position in its patent owner response wherein “storage element” was construed as “an element of an energy transfer system that stores non-negligible amounts of energy from an input electromagnetic signal.” The APA required the Board to give Intel “adequate notice and an opportunity to respond under the new construction” proffered in ParkerVision’s patent owner response. As in Axonics, Inc. v. Medtronic, Inc., 75 F.4th 1374 (Fed. Cir. 2023), the court held that “where a patent owner in an IPR first proposes a claim construction in a patent owner response, a petitioner must be given the opportunity in its reply to argue and present evidence of anticipation or obviousness under the new construction….” Id. at 1384. Intel did just that. Intel’s reply countered that ParkerVision’s non-obviousness position that the cited prior art did not disclose the claimed “storage element” because it was not in an energy transfer system is misplaced because that term is not restricted to be an element of an energy transfer system.

Pursuant to the APA, the Board may not change theories mid-stream without giving the parties reasonable notice of its change. The Board’s adopting of Intel’s claim construction did not “change theories midstream without giving the parties reasonable notice of its change.” “Once ParkerVision introduced a claim construction argument into the proceeding through its patent owner response, Intel was entitled in its reply to respond to that argument and explain why that construction should not be adopted.” And, ParkerVision had an opportunity to respond to Intel’s proposed construction by filing its sur-reply, which continued to press for its own claim construction.

However, with regard to patentability (non-obviousness), ParkerVision added in its sur-reply, for the first time, that the cited prior art’s capacitors stored only a negligible amount of energy because “non-negligible” must be measured relative to the available energy of the input EM signal. This part of ParkerVision’s sur-reply was stricken by the Board. ParkerVision’s patent owner response asserted that the cited prior art capacitors must store non-negligible amounts of energy, but did not assert that the reference failed to meet that requirement (instead, merely arguing the capacitors are not part of an energy transfer system). Accordingly, its sur-reply offered a new theory of patentability. There is no abuse of discretion in declining to consider a new theory of patentability raised for the first time in sur-reply.

ParkerVision further asserted that its sur-reply arguments addressed allegedly new arguments in Intel’s reply. But, the Board noted:

[I]f [ParkerVision] believed [Intel’s] Reply raised an issue that was inappropriate for a reply brief or that [ParkerVision] needed a greater opportunity to respond beyond that provided by our Rules (e.g., to include new argument and evidence in its Sur-reply), it was incumbent upon [ParkerVision] to contact [the Board] and request authorization for an exception to the Rules. [ParkerVision] did not do so. [ParkerVision] did not request that its Sur-reply be permitted to include arguments and evidence that would otherwise be impermissible in a sur-reply.

The court faulted ParkerVision for not availing itself of the available procedural mechanisms. For these reasons, the court found no abuse of discretion in the Board’s exclusion of part of ParkerVision’s sur-reply.

Takeaways:

The existence of district court claim construction positions do not guarantee the same claim constructions being adopted by the Board. And, the Federal Circuit reviews claim construction issues de novo.

For the patent owner’s sur-reply, be wary of potentially “new” patentability positions being advanced that were not originally raised in the patent owner response. If any such “new” patentability positions are taken, be cognizant of the procedural mechanism to contact the Board and request authorization for an exception to the Rules to include arguments and/or evidence that may otherwise be impermissible in a sur-reply.

« Previous Page — Next Page »