Box designs for dispensing wires and cables affirmed as functional, not registrable as trade dresses

WHDA Blogging Team | December 23, 2020

In re: Reelex Packaging Solution, Inc. (nonprecedential)

November 5, 2020

Moore, O’Malley, Taranto (Opinion by O’Malley)

Summary

In a nonprecedential opinion, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the “CAFC”), affirmed the decision of the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (the “TTAB”), upholding the examining attorney’s refusal to register two box designs for electric cables and wire as trade dresses on grounds that the designs are functional.

Details

Reelex filed two trade dress applications for coils of cables and wire in International Class 9.

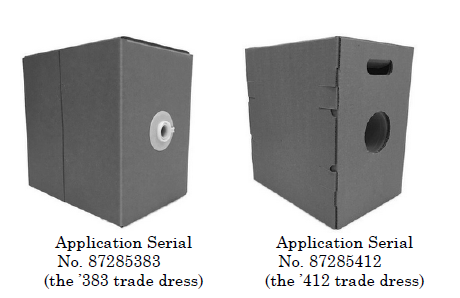

The trade dress of Application Serial No. 87285383 (the ‘383 trade dress) is described as follows:

The mark consists of trade dress for a coil of cable or wire, the trade dress comprising a box having six sides, four sides being rectangular and two sides being substantially square, the substantially square sides both having a length of between 12 and 14 inches, the rectangular sides each having a length of between 12 and 14 inches and a width of between 7.5 and 9 inches and a ratio of width to length of between 60% and 70%, one, and only one rectangular side having a circular hole of between 0.75 and 1.00 inches in the exact middle of the side with a tube extending through the hole and through which the coil is dispensed from the package, the tube having an outer end extending beyond an outer surface of the rectangular side, and a collar extending around the outer end of the tube on the outer surface of the rectangular side of the package, and one square side having a line folding assembly bisecting the square side.

The trade dress of Application Serial No. 87285412 (the ‘412 trade dress) is described as follows:

The mark consists of trade dress for a coil of cable or wire, the trade dress comprising a box having six sides, four sides being rectangular and two sides being substantially square, the substantially square sides both having a length of between 13 and 21 inches, the rectangular sides each having a length of the same length of the square sides and a width of between 57% and 72% of the size of the length, one, and only one rectangular side having a circular hole of 4.00 inches in the exact middle of the side with a tube extending in the hole and through which the coil is dispensed from the package, one square side having a tongue and a groove at an edge adjacent the rectangular side having the circular opening, and the rectangular side having the circular opening having a tongue and a groove with the tongue of each respective side extending into the groove of each respective side at a corner therebetween.

The examining attorney refused the applications, finding the design of the boxes as being functional and non-distinctive. Further, the examining attorney found that the designs do not function as trademarks to indicate the source of the goods. On an appeal to the TTAB, the Board affirmed the examining attorney to register on the grounds of functionality and distinctiveness. Regarding functionality, the Board found that the features of these boxes – the rectangular shape, built-in handle for the ‘412 design, and dimensions of the boxes and the size and placement of the payout tubes and payout holes, are “clearly dictated by utilitarian concerns.” The Board also found that the payout holes and their position on the boxes allowed users easy access and twist-free dispensing.

While the Board found above to be sufficient evidence to uphold the functionality refusal, the Board went further to considered the following four factors from In re Morton-Norwich Products, Inc., 671 F.2d 1332 (CCPA 1982):

(1) the existence of a utility patent that discloses the utilitarian advantages of the design sought to be registered;

(2) advertising by the applicant that touts the utilitarian advantages of the design;

(3) facts pertaining to the availability of alternative designs; and

(4) facts pertaining to whether the design results from a comparatively simple or inexpensive method of manufacture.

- Existence of a utility patent

With regard to the first factor, Reelex submitted five utility patents relating to the applied-for marks:

- U.S. Patent No. 5,810,272 for a Snap-On Tube and Locking Collar for Guiding Filamentary Material Through a Wall Panel of a Container Containing Wound Filamentary Material;

- U.S. Patent No. 6,086,012 for Combined Fiber Containers and Payout Tube and Plastic Payout Tubes;

- U.S. Patent No. 6,341,741 for Molded Fiber and Plastic Tubes;

- U.S. Patent No. 4,160,533 for a Container with Octagonal Insert and Corner Payout; and

- U.S. Patent No. 7,156,334 for a Pay-Out Tube.

The Board found that the patents revealed several benefits of various features of the two boxes, weighing in favor of finding the designs of the two boxes to be functional.

- Advertising by the applicant

The second factor also weighed in favor of finding functionality. Reelex’s advertising materials repeatedly touted the utilitarian advantages of the boxes, which allow for dispensing of cable or wire without kinking or tangling. The boxes’ recyclability, shipping, and storage advantages were also being touted. The evidence weighed in favor of finding functionality.

- Alternative designs

The Board explained that in cases where patents and advertising demonstrate functionality of designs, there is no need to consider the availability of alternative designs. Nevertheless, the Board considered evidence submitted by Reelex, and found the evidence to be speculative and contradictory to its own advertising and patents. Therefore, the Board found the evidence to be unpersuasive.

- Comparatively simple or inexpensive method of manufacture

Regarding this last factor, the Board found no evidence of record regarding the cost or complexity of manufacturing the trade dress.

Considering and analyzing the case using the Morton-Norwich factors, the Board found the design of Reelex’s trade dress to be “essential to the use or purpose of the device” as used for “electric cable and wires.”

On appeal, Reelex argued that evidence shows that the trade dresses at issue “provide no real utilitarian advantage to the user.” In addition, Reelex argued that the Board erred in failing to consider evidence of alternative designs.

The CAFC found there to be substantial evidence to support the Board’s finding of multiple useful features in the design of the boxes, and these features were properly analyzed by the Board as a whole and in combination, and the Board did not improperly dissect the designs of the two trade dresses into discrete design features. The CAFC also found there to be sufficient evidence supporting the Board’s finding of functionality using the Morton-Norwich factors.

As to whether the Board considered Reelex’s evidence of alternative designs, the Board expressly considered Reelex’s evidence of alternative designs, and found the evidence to be both speculative and contradictory. For example, although the declaration submitted by Reelex stated that the shape of the package, as well as the shape, size, and location of the payout hole, were merely ornamental, Reelex’s utility patents repeatedly refer to the utilitarian advantages of the two box designs.

Therefore, the CAFC affirmed the decision of the Board, upholding the examining attorney’s refusal to register the two trade dress applications because they are functional.

Takeaway

- Functional designs cannot be registered as a trade dress. If a utility patent exists for a design, it is likely that the same design cannot also be protected as a trade dress.

- Note that there is an overlap in design patent and trade dress. Existence of a design patent does not preclude an applicant from filing a trademark application for the same design.

Printed Matter Challenge to Patent Eligiblity

John Kong | December 11, 2020

C R Bard Inc. v. AngioDynamics Inc.

November 10, 2020

Opinion by: Reyna, Schall, and Stoll (November 10, 2020).

Summary:

A vascular access port patent recited “identifiers” that were not given patentable weight under the printed matter doctrine. Printed matter constitutes an abstract idea under Alice step 1. Nevertheless, even though printed matter was not given any patentable weight and the claim was directed to printed matter under Alice step 1, the claims were found eligible under Alice step 2.

Background:

Bard sued AngioDynamics in the District of Delaware for infringing U.S. Patent Nos. 8,475,417, 8,545,460, and 8,805,478. One representative claim is claim 1 of the ‘417 patent:

An assembly for identifying a power injectable vascular access port, comprising:

a vascular access port comprising a body defining a cavity, a septum, and an outlet in communication with the cavity;

a first identifiable feature incorporated into the access port perceivable following subcutaneous implantation of the access port, the first feature identifying the access port as suitable for flowing fluid at a fluid flow rate of at least 1 milliliter per second through the access port;

a second identifiable feature incorporated into the access port perceivable following subcutaneous implantation of the access port, the second feature identifying the access port as suitable for accommodating a pressure within the cavity of at least 35 psi, wherein one of the first and second features is a radiographic marker perceivable via x-ray; and

a third identifiable feature separated from the subcutaneously implanted access port, the third feature confirming that the implanted access port is both suitable for flowing fluid at a rate of at least 1 milliliter per second through the access port and for accommodating a pressure within the cavity of at least 35 psi.

Vascular access ports are implanted underneath a patient’s skin to allow injection of fluid into the patient’s veins on a regular basis without needing to start a new intravenous line every time. Certain procedures, such as computed tomography (CT) imaging, required high pressure and high flow rate injections through such ports. However, traditional vascular access ports were used for low pressure and flow rates, and sometimes ruptured under high pressures and flow rates. FDA approval was eventually required for vascular access ports that were structurally suitable for power injections under high pressures and flow rates. To distinguish between FDA approved power injection ports versus traditional ports, Bard used the claimed radiographic marker (e.g., “CT” etched in titanium foil on the device) on its FDA approved power injection ports that could be detected during an x-ray scan typically performed at the start of a CT procedure. Additional identification mechanisms included small bumps that were palpable through the skin, and labeling on device packaging and items that can be carried by the patient (e.g., keychain, wristband, sticker). AngioDynamics also received FDA approval for its own power injection vascular access ports including a scalloped shaped identifier and a radiographic “CT” marker.

AngioDynamics raised ineligibility under §101 using the printed matter doctrine to nix patentable weight for the claimed identifiers in its motion to dismiss the complaint, its summary judgment motion, and later during the trial on an oral JMOL motion. In advance of the trial, the district court requested a report and recommendation from a magistrate judge regarding whether “radiographic letters” and “visually perceptible information” limitations in the claims were entitled patentable weight under the printed matter doctrine, as part of claim construction. The district court judge adopted the magistrate judge’s recommendations on the printed matter and ultimately granted AngioDynamic’s JMOL motion for ineligiblity.

The Printed Matter Doctrine:

This decision summarized the printed matter doctrine as follows:

- “printed matter” is not patentable subject matter

- the printed matter doctrine prohibits patenting printed matter unless it is “functionally related” to its “substrate,” which includes the structural elements of the claim

- while this doctrine started out with literally “printed” material, it has evolved over time to encompass “conveyance of information using any medium,” and “any information claimed for its communicative content.”

- “In evaluating the existence of a functional relationship, we have considered whether the printed matter merely informs people of the claimed information, or whether it instead interacts with the other elements of the claim to create a new functionality in a claimed device or to cause a specific action in a claimed process.”

Here, there is no dispute that the claims include printed matter (markers) “identifying” or “confirming” suitability of the port for high pressure or high flow rate. These markers inform people of the claimed information – suitability for high pressure or high flow rate.

Bard asserted that the markers provided a new functionality for the port to be “self-identifying.” This reasoning was rejected because mere “self-identification” being new functionality “would eviscerate our established case law that ‘simply adding new instructions to a known product’ does not create a functional relationship.” For instance, marking of meat and wooden boards with information concerning the product does not create a functional relationship between the printed information and the substrate.

Bard asserted that the printed matter is functionally related to the power injection step of the method claims because medical providers perform the power injection “based on” the markers. This reasoning was also rejected because the claims did not recite any such causal relationship.

Accordingly, the Federal Circuit held that the markers and the information conveyed by the markers, i.e., that the ports are suitable for power injection, is printed matter not entitled to patentable weight.

Nevertheless, despite the holding about printed matter not given patentable weight, the Federal Circuit still found the claims to be patent eligible under Alice step 2.

Before getting to Alice step 2, the Federal Circuit equates printed matter to an abstract idea, citing to an eighty year old decision “where the printed matter, is the sole feature of alleged novelty, it does not come within the purview of the statute, as it is merely an abstract idea, and, as such, not patentable.” The court further equates this to post-Alice decisions (Two-Way Media, Elec. Pwr Grp, Digitech) recognizing that “the mere conveyance of information that does not improve the functioning of the claimed technology is not patent eligible subject matter. under §101.” “We therefore hold that a claim may be found patent ineligible under §101 on the grounds that it is directed solely to non-functional printed matter and the claim contains no additional inventive concept.”

However, with regard to Alice step 2’s inventive concept, the court viewed “the focus of the claimed advance is not solely on the content of the information conveyed, but also on the means by which that information is conveyed” (i.e., via the radiographic marker). Bard admitted that use of radiographically identifiable markings on implantable medical devices was known in the prior art. Nevertheless, “[e]ven if the prior art asserted by AngioDynamics demonstrated that it would have been obvious to combine radiographic marking with the other claim elements, that evidence does not establish that radiographic marking was routine and conventional under Alice step two.” “AngioDynamics’ evidence is not sufficient to establish as a matter of law, at Alice step two, that the use of a radiographic marker, in the ‘ordered combination’ of elements claimed, was not an inventive concept.” Even with regard to the corresponding method claim, “while the FDA directed medical providers to verify a port’s suitability for power injection before using a port for that purpose, it did not require doing so via imaging of a radiographic marker…[t]here is no evidence in the record that such a step was routinely conducted in the prior art.”

Takeaways:

- The printed matter doctrine not only precludes patentable weight for §§102 and 103 inquiries, but also raises abstract idea issues under Alice step 1.

- This case also reminds us of the eligibility hurdles for data processing inventions, with Two-Way Media “concluding that claims directed to the sending and receiving of information were unpatentable as abstract where the steps did not lead to any ‘improvement in the functioning of the system;’” Elec. Pwr Grp “holding that claims directed to ‘a process of gathering and analyzing information of a specified content, then displaying the results, and not any particular assertedly inventive technology for performing those functions’ are directed to an abstract idea;” and Digitech stating that “data in its ethereal, non-physical form is simply information that does not fall under any of the categories of eligible subject matter under section 101.”

- For Alice step 2, this case exemplifies the high bar for establishing “routine and conventional.” Here, the patentee’s admission that radiographic marking on implanted medical devices is known in the prior art was not enough to establish “routine and conventional.” Even prior art that demonstrates the obviousness of combining radiographic marking with the other claim elements was also not enough to establish “routine and conventional.”

- For Alice step 2, this case may exemplify the breadth of what constitutes an inventive concept in “an ordered combination.” The court does not specify exactly what the “ordered combination” was here. Perhaps, the “significantly more” (beyond the abstract idea of the printed matter) could simply be the combination of a radiographic marker and a port.

Dependent Claims Cannot Broaden an Independent Claim from Which They Depend

Bo Xiao | December 4, 2020

Network-1 Technologies, Inc. v. Hewlett-Packard Company, Hewlett-Packard Enterprise Company

Before PROST, Chief Judge, NEWMAN and BRYSON, Circuit Judges.

Summary

The Federal Circuit reversed, in part, and affirmed, in part, the district court’s decision and ordered a new trial on infringement. Because the district court erred in construing one patent claim, the Federal Circuit concluded that the district court’s erroneous claim construction established prejudice towards Network-1. The Federal Circuit also affirmed the district court’s judgment that the dependent claims did not improperly broaden one of the asserted claims.

Background

Network-1 Technologies, Inc. (“Network-1”) owns U.S. Patent 6,218,930 (the ‘930 patent), entitled “Apparatus and Method for Remotely Powering Access Equipment over a 10/100 Switched Ethernet Network,” which sued Hewlett-Packard (“HP”) for infringement in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas. The jury found the patent not infringed and invalid. But the district court granted Network-1’s motion for judgment as a matter of law (“JMOL”) on validity following post-trial motions.

Network-1 appealed the district court’s final judgment that HP does not infringe the ’930 patent, arguing the district court erred in its claim construction on “low level current” and “main power source.” HP cross-appealed the district court’s estoppel determination in raising certain validity challenges under 35 U.S.C. § 315(e)(2) based on HP’s joinder to an inter partes review (“IPR”) before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“the Board”). Also, HP argued that Network-1 improperly broadened claim 6 of the ’930 patent by adding two dependent claims 15 and 16.

Discussion

The ’930 patent discloses an apparatus and methods for allowing electronic devices to automatically determine if remote equipment is capable of accepting remote power over Ethernet. On appeal, the arguments on the alleged infringement are drawn towards claim 6 as follows.

6. Method for remotely powering access equipment in a data network, comprising,

providing a data node adapted for data switching, an access device adapted for data transmission, at least one data signaling pair connected between the data node and the access device and arranged to transmit data therebetween, a main power source connected to supply power to the data node, and a secondary power source arranged to supply power from the data node via said data signaling pair to the access device,

delivering a low level current from said main power source to the access device over said data signaling pair,

sensing a voltage level on the data signaling pair in response to the low level current, and

controlling power supplied by said secondary power source to said access device in response to a preselected condition of said voltage level.

Network-1 argued that the district court erroneously construed the claim terms “low level current” and “main power source” in claim 6. About “low level current,” the district court imposed both an upper bound (the current level cannot be sufficient to sustain start up) … and a lower bound (the current level must be sufficient to begin startup). Network-1 admitted that the term “low level current” describes current that cannot “sustain start up” but disagreed with the district court’s construction that the current has a lower bound at a level sufficient to begin start up.

The Federal Circuit reviewed the arguments and made it clear that “[T]he claims themselves provide substantial guidance as to the meaning of particular claim terms” and “the specification is the single best guide to the meaning of a disputed term.” It has been pointed out that the claim phrase is not limited to the word “low,” and the claim construction analysis should not end just because one reference point has been identified. The Federal Circuit further explained that the claim phrase “low level current” does not preclude a lower bound by using the word “low.” Rather, in the same way the phrase should be construed to give meaning to the term “low,” the phrase must also be construed to give meaning to the term “current.” The term “current” necessarily requires some flow of electric charge because “[i]f there is no flow, there is no ‘current.’” Therefore, the Federal Circuit confirms that the district court correctly construed the phrase “low level current.”

However, the Federal Circuit held that the district court erred in its construction of “main power source” in the patent claims resulting in prejudice towards Network-1. The district court construed “main power source” as “a DC power source,” thereby excluding AC power sources from its construction. The Federal Circuit concluded that the correct construction of “main power source” includes both AC and DC power sources. Although HP argued that the erroneous claim construction was harmless and no accused product meets the claim limitation “delivering a low level current from said main power source,” the Federal Circuit confirmed that Network-1 has established that the claim construction prejudiced it because the evidence shows that HP relied on the district court’s erroneous construction for its argument. The district court’s erroneous claim construction of “main power source” is entitled Network-1 to a new trial on infringement.

On cross-appeal, HP argued that the district court erred in concluding that HP was statutorily estopped from raising certain invalidity. In this case, HP did not petition for IPR but relied on the joinder exception to the time bar under § 315(b). HP first filed a motion to join the Avaya IPR with a petition requesting review based on grounds not already instituted. The Board correctly denied HP’s first request but later granted HP’s second joinder request, which petitioned for only the two grounds already instituted. The Federal Circuit reasoned that “HP, however, was not estopped from raising other invalidity challenges against those claims because, as a joining party, HP could not have raised with its joinder any additional invalidity challenges.” A party is only estopped from challenging claims in the final written decision based on the grounds that it “raised or reasonably could have raised” during the inter partes review (IPR). Hence, the Federal Circuit ruled that HP was not statutorily estopped from challenging the asserted claims of the ’930 patent, which were not raised in the IPR and could not have reasonably been raised by HP.

Prior to reexamination, claim 6 of the ’930 patent was construed to require the “secondary power source” to be physically separate from the “main power source.” But during the reexamination, Network-1 added claims 15 and 16, which depended from claim 6 and respectively added the limitations that the secondary power source “is the same source of power” and “is the same physical device” as the main power source. HP argued that claim 6 and the other asserted claims are invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 305 because Network-1 improperly broadened claim 6 by adding claim 15 and 16 in the reexamination. However, the Federal Circuit does not agree that claim 6 is invalid for improper broadening based on the addition of claims 15 and 16. First, a patentee is not permitted to enlarge the scope of a patent claim during reexamination. The broadening inquiry involves two steps: (1) analyzing the scope of the claim prior to reexamination and (2) comparing it with the scope of the claim subsequent to reexamination. The Federal Circuit’s broadening inquiry begins and ends with claim 6. Because claim 6 was not itself amended, the scope of claim 6 was not changed as a result of the reexamination. Where the scope of claim 6 has not changed, there has not been improper claim broadening. Dependent claims cannot broaden an independent claim from which they depend. Accordingly, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s conclusion that claim 6 and the other asserted claims are not invalid due to improper claim broadening.

Takeaway

- A party is only estopped from challenging claims in the final written decision based on grounds that it “raised or reasonably could have raised” during the inter partes review (IPR).

- Dependent claims cannot broaden an independent claim from which they depend.

What Does It Mean To Be Human?

Adele Critchley | November 26, 2020

Immunex Corp v. Sanofi-Aventis U.S. LLC

Prost, Reyna and Taranto.Opinion by Prost

October 13, 2020

Summary

This is a consolidated appeal from two Patent and Trademark Appeal Board (“Board”) decisions in Inter partes reviews (IPR) of US Patent No. 8,679,487 (‘487 patent) owned by Immunex. In the first IPR the Board invalidated all challenged claims. Immunex appealed the construction of the claim term “human antibodies.” In the other IPR, involving a subset of the same claims, the Board did not invalidate the patent for reason of inventorship. Sanofi appealed the Boards inventorship determination.

Briefly, the CAFC agreed with the Board’s claim construction and affirmed the invalidity decision. Since this left no claims valid, the CAFC dismissed Sanofi’s inventorship appeal.

The ’487 patent is directed to antibodies that bind to human interleukin-4 (IL-4) receptor. This appeal concerned what “human antibody” means in this patent. That is, in the context of this patent, must a human antibody be entirely human, or does it include partially human, for example humanized?

Amid infringement litigation, Sanofi filed three IPR’s against the ‘487 patent, two if which were instituted. In one final decision the Board concluded that the claims were unpatentable as obvious over two references, Hart and Schering-Plough. Hart describes a murine antibody that meet all the limitations of claim 1 except that it is fully murine, so not human at all. The Schering-Plough reference teaches humanizing murine antibodies.

In response, Immunex insisted that the Board had erred in construction of “human antibody” to include humanized antibodies.

After Appellate briefing was complete, Immunex filed with the PTO a terminal disclaimer of its patent. The PTO accepted it, and the patent expired May 26, 2020, just over two months prior to oral arguments. Immunex then filed a citation apprising the CAFC of (but not explaining the reason for) its terminal disclaimer and asking the court to change the applicable construction standard.

Specifically, in all newly filed IPRs, the Board now applies the Phillips district-court claim construction standard. However, when Sanofi filed its IPR, the Board applied this standard to expired patents only. To unexpired patents, it applied the Broadest Reasonable Interpretation (BRI) standard.

Immunex urged the CAFC to apply Phillips citing Wasica Finance GmbH v., Continental Automotive Systems, Inc., 853 F.3d 1272, 1279 (Fed. Cir. 2017) and In re CSB-System International 832 F. 3d 1335, as support. However, unlike here, the patents at issues in these cases had expired before the Board’s decision. The CAFC noted that it had applied the Phillips standard when a patent expired on appeal. Nonetheless, the CAFC clarified that in these cases the patent terms had expired as expected and not cut short by a litigant’s terminal disclaimer.

Accordingly, the CAFC affirmed it will review the Board’s claim construction under the BRI standard.

Initially, the CAFC turned to the intrinsic record, specifically, the claims, the specification, and the prosecution history.

The CAFC noted that the claims themselves were not helpful as the dependent claims provided no further guidance.

Next, the CAFC noted that while the specification gave no actually definition, the usage of “human” throughout the specification confirmed its breadth. Specifically, the specification contrasts “partially human’ with “fully human.” For instance, the specification states that “an antibody…include, but are not limited to, partially human…. fully human.” Thus, the specification makes it clear that “human antibody” is a broad category encompassing both “fully” and “partially.”

Immunex insisted that the Board undervalued the prosecution history. While the CAFC agreed, it concluded the prosecution history supported the Board’ construction.

First, they noted that Immunex had used the term “fully human” and “human” in the same claim of another of its patents in the same family. Next, claim 1 as originally presented merely stated “an isolated antibody” and “human” were added during prosecution.

As a result, a dependent claim which recited ‘a human, partially human, humanized or chimeric antibody’ was cancelled. Immunex suggested that the amendment “surrendered” the partially human embodiment. The CAFC disagreed.

The Board noted that “human” was not added to overcome an anticipating reference that disclosed ‘nonhuman.’ The CAFC also noted that the claim language does not require the exclusion of partially human embodiments. Thus, the CAFC held that nothing indicates that “human” was added to limit the scope to fully human.

The CAFC noted that in a post-amendment office action, the Examiner expressly wrote that the amended “human” antibodies encompassed “humanized” antibodies and that Immunex had made no effort to correct this understanding.

Next, the CAFC addressed the role of extrinsic evidence. Immunex argued that the Board had failed to establish how a person of ordinary skill in the art would have understood the term. Immunex had provided expert testimony to argue that “human antibody” would have been limited to “fully human.”

The CAFC held that while it is true that they seek the meaning of a claim term from the perspective of a person of ordinary skill in the art, the key is how that person would have understood the term in view of the specification. That, while extrinsic evidence may illuminate a well-understood technical meaning, that does not mean that litigants can introduce ambiguity in a way that disregards usage in the patent itself.

Here, the extrinsic evidence provided conflicts the intrinsic evidence. Priority is given to the intrinsic evidence.

Lastly, the CAFC discussed the Boards’ departure from an earlier court’s claim construction. That is, in the litigation that prompted this IPR, a district court construed “human” to mean “fully human” only, under the narrower Phillips-based construction. However, the CAFC reiterated that the Board “is not generally bound by a previous judicial construction of a claim term.”

Thus, to conclude, the CAFC affirmed the Board’s claim construction under the BRI standard, and thus its invalidity judgment based thereon.

Take-away

- Claim drafting – words matter

- The importance of dependent claims

- Be mindful of amendments made during prosecution that are not done for the purpose of overcoming prior art.

- In claim construction, intrinsic evidence has priority over extrinsic evidence when they conflict.

- Be mindful of comments made by the Examiner during prosecution in an action (office action, notice of allowance, etc.,) regarding interpretation of the claims.