Claim construction of a non-functional term in an apparatus claim; proof of vitiation against infringement under the doctrine of equivalents

WHDA Blogging Team | March 29, 2021

Edgewell Personal Care Brands, LLC v. Munchkin, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2021) (Case No. 2020-1203)

March 9, 2021

Newman, Moore, and Hughes. Court opinion by Moore

Summary

On appeals from the district court for summary judgment of noninfringement of two patents, both directed to a cassette to be installed when a diaper pail system is in use, the Federal Circuit unanimously vacated the summary judgment of noninfringement of one patent because of erroneous claim construction, with caution that it is usually improper to construe non-functional claim terms in apparatus claims in a way that makes infringement or validity turn on the way an apparatus is later put to use. Furthermore, the Federal Circuit unanimously reversed the summary judgment of noninfringement of the other patent under the doctrine of equivalents because of erroneous application of the vitiation theory in the context of summary judgment, with caution that courts should be cautious not to shortcut the inquiry for infringement under the doctrine of equivalents by identifying a ‘binary’ choice in which an element is either present or ‘not present.’”

Details

I. Background

(i) The Patents in Dispute

U.S. Patent Nos. 8,899,420 (“the ’420 patent”) and 6,974,029 (“the ’029 patent”) are directed to a cassette to be installed when a diaper pail system is in use.

The ’420 patent is directed to a cassette with a “clearance” located in a bottom portion of the cassette. Claim 1 is the representative of the ’420 patent, which recites:

1. A cassette for packing at least one disposable object, comprising: an annular receptacle including an annular wall delimiting a central opening of the annular receptacle, and a volume configured to receive an elongated tube of flexible material radially outward of the annular wall; a length of the elongated tube of flexible material disposed in an accumulated condition in the volume of the annular receptacle; and an annular opening at an upper end of the cassette for dispensing the elongated tube such that the elongated tube extends through the central opening of the annular receptacle to receive disposable objects in an end of the elongated tube,

wherein the annular receptacle includes a clearance in a bottom portion of the central opening, … (emphasis added).

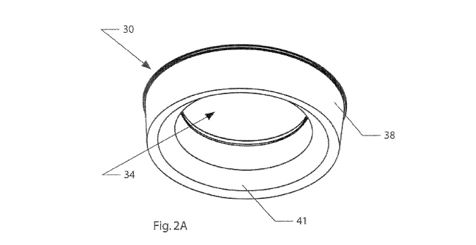

Fig. 2A of the ’420 patent, reproduced below, illustrates a bottom perspective view of a cassette 30 to be used with an apparatus 10 (not shown in the figure) for packaging disposable objects (34: a central opening; 38: a bottom annular receptacle; a chamfer clearance 41).

The ’029 patent is directed to a cassette with a cover extending over pleated tubing housed therein. Claim 1 is the representative of the ’029 patent, which recites:

1. A cassette for use in dispensing a pleated tubing comprising:

an annular body having a generally U shaped cross-section defined by an inner wall, an outer wall and a bottom wall joining a lower part of said inner and outer walls, said walls defining a housing in which the pleated tubing is packed in layered form;

an annular cover extending over said housing; said cover having an inner portion extending downwardly and engaging an upper part of said inner wall of said body and a top portion extending over said housing; said top portion including a tear-off outwardly projecting section having an outer edge engaging an upper part of said outer wall of said annular body; said tear-off section, when torn-off, leaving a peripheral gap to allow access and passage of said tubing therebetween; said downwardly projecting inner portion having an inclined annular area defining a funnel to assist in sliding said tubing when pulled through a central core defined by said inner wall of said body; and … (emphasis added).

(ii) The District Court

Edgewell Personal Care Brands, LLC, and International Refills Company, Ltd. (“Edgewell”) sued Munchkin, Inc. (“Munchkin”) in the United States District Court for the Central District of California (“the district court”) for infringement of claims of the ’420 patent and ’029 patent.

Edgewell manufactures and sells the Diaper Genie, which is a diaper pail system that has two main components: (i) a pail for collection of soiled diapers; and (ii) a replaceable cassette that is placed inside the pail and forms a wrapper around the soiled diapers.

Edgewell accused Second and Third Generation refill cassettes, which Munchkin marketed as being compatible with Edgewell’s Diaper Genie-branded diaper pails.

After the district court issued a claim construction order, construing terms of both the ’420 patent and the ’029 patent, Edgewell continued to assert literal infringement for the ’420 patent, and infringement under the doctrine of equivalents (“the DoE”) for the ’029 patent. Munchkin moved for, and the district court granted, summary judgment of noninfringement of both patents. Edgewell appealed.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit (“the Court”) unanimously vacated the summary judgment of noninfringement (literal infringement) of the ’420 patent, reversed the summary judgment of noninfringement (infringement under the DoE) of the ’029 patent, and remanded the case to the district court for further proceedings.

(i) The ’420 Patent

There was no dispute that the cassette itself contained a clearance when it is not installed in the pail. Rather, the dispute focused on whether the claims required a clearance space between the annular wall defining the chamfer clearance and the pail itself when the cassette was installed (emphasis added). The district court determined that “clearance” required space after cassette installation and construed the clearance as “the space around [interfering] members that remains (if there is any), not the space where the interfering member or cassette is itself located upon insertion” (emphasis added).

The Court held that the district court erred in construing the term “clearance” in a manner dependent on the way the claimed cassette is put to use in an unclaimed structure, and vacated the district court’s grant of summary judgment of noninfringement of the ’420 patent.

On the merits, the Court stated that it is usually improper to construe non-functional claim terms in apparatus claims in a way that makes infringement or validity turn on the way an apparatus is later put to use because an apparatus claim is generally to be construed according to what the apparatus is, not what the apparatus does.

The Court moved on to argue that, absent an express limitation to the contrary, the term “clearance” should be construed as covering all uses of the claimed cassette as the parties do not dispute that the ’420 patent claims are directed only to a cassette. The Court looked into the specification to find that, in nearly all of the disclosed embodiments, the specification suggests that the cassette clearance mates with a complimentary structure in the pail such that there is “engagement” (emphasis added). Thus, the Court concluded that the claim does not require a clearance after insertion. In other words, the specification, taken as a whole, does not support the district court’s construction which would preclude such engagement when the cassette is inserted into the pail (emphasis added).

In conclusion, the Court vacated the district court’s grant of summary judgment of noninfringement of the ’420 patent and remanded the case because the Court held that the district court erred in its construction of the term “clearance.”

(ii) The ’029 Patent

The district court construed “annular cover” in the ’029 patent as “a single, ring-shaped cover, including at least a top portion and an inner portion that are parts of the same structure” (emphasis added). Edgewell did not dispute the construction. Instead, Edgewell sought infringement under the DoE for the ’029 patent because Munchkin’s accused Second and Third Generation cassettes each include a two-part annular cover (emphasis added). The district court granted summary judgment of noninfringement of the ’029 patent under the DoE. because the district court determined that no reasonable jury could find that Munchkin’s Second and Third Generation Cassettes satisfy the ’029 patent’s “annular cover” and “tear-off section” limitations under the DoE given that favorable application of the DoE would effectively vitiate the ‘tear-off section’ limitation (emphasis added).

The Court affirmed the district court’s claim construction in view of the plain language of the claims and the written description of the ’029 patent.

In contrast, the Court disagreed to the district court’s vitiation theory under the DoE. While the Court reconfirmed the vitiation theory by stating that vitiation has its clearest application “where the accused device contain[s] the antithesis of the claimed structure”(citing Planet Bingo, LLC v. GameTech Int’l, Inc., 472 F.3d 1338, 1345 (Fed. Cir. 2006)), the Court cautioned that “[c]ourts should be cautious not to shortcut this inquiry by identifying a ‘binary’ choice in which an element is either present or ‘not present’” (citing Deere & Co. v. Bush Hog, LLC, 703 F.3d 1356–57 (Fed. Cir. 2012)).

Applying these concepts to the facts of this case, the Court conclude that the district court erred in evaluating this element as a binary choice between a single-component structure and a multi-component structure, rather than evaluating the evidence to determine whether a reasonable juror could find that the accused products perform substantially the same function, in substantially the same way, achieving substantially the same result as the claims.

Citing Edgewell’s expert testimony, the Court concluded that the detailed application of the function-way-result test, supported by deposition testimony from Munchkin employees, is sufficient to create a genuine issue of material fact for the jury to resolve and, therefore, is sufficient to preclude summary judgment of noninfringement under the DoE.

In conclusion, the Court reversed the district court’s grant of summary judgment of noninfringement of the ’029 patent under the DoE and remanded the case.

Takeaway

· Claim construction: A term in a claim should be construed as covering all uses of the claimed subject matter.

· Infringement under the DoE: Proof of vitiation requires more than identifying a binary choice in which an element is either “present” or “not present.” Instead, the proof still requires failure of passing the function-way-result test.

Tags: claim construction > doctrine of equivalents > summary judgment > vitiation

Trademark licensing agreements are not distinguishable from other types of contracts – the contracting parties are generally held to the terms for which they bargained

WHDA Blogging Team | March 23, 2021

Authentic Apparel Group, LLC, et al. v. United States

March 4, 2021

Lourie, Dyk, Stoll (opinion by Lourie)

Summary

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“the CAFC”) upheld the grant of summary judgement by United States Court of Federal Claims (“the Claims Court”), finding the plaintiff’s arguments unpersuasive. The CAFC found trademark licensing agreement to not be any different from other types of contracts, and there was no legal or factual reason to deviate from a plain reading of the exculpatory clauses in the trademark license agreement between the plaintiff and the defendant.

Details

Department of the Army (“Army”) and Authentic Apparel Group, LLC (“Authentic”) entered into a nonexclusive license for Authentic to manufacture and sell clothing bearing the Army’s trademarks in exchange for royalties. The license agreement stated that prior to any sale or distribution, Authentic must submit to the Army all products and marketing materials bearing the Army’s trademark for the Army’s written approval. The license also included exculpatory clauses that exempted the Army from liability for exercising its discretion to deny approval.

Between 2011 and 2014, Authentic submitted nearly 500 requests for approval to the Army, of which 41 were denied. During this time period, several formal notices were sent to Authentic, stating Authentic’s failures to timely submit royalty reports and pay royalties. Authentic eventually paid royalties through 2013, but on November 24, 2014, but expressed its intention of not paying outstanding royalties for 2014, and that it would sue the government for damages.

On January 6, 2015, Authentic and Ruben filed a complaint in the Claims Court for breach of contract. The allegations of breach were based on “the Army’s denial of the right to exploit the goodwill associated with the Army’s trademarks, refusal to permit Authentic to advertise its contribution to certain Army recreation programs, delay of approval for a financing agreement for a footwear line, and denial of approval for advertising featuring the actor Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson.” The Claims Court dismissed Ruben as a plaintiff for lack of standing. Authentic subsequently amended its complaint to include an allegation that “the Army breached the implied duty of good faith and fair dealings by not approving the sale of certain garments.”

One November 27, 2019, the Claims Court granted the government’s motion for summary judgment, determining that Authentic could not recover damages based on the Army’s exercise of discretion in view of the express exculpatory clauses included in the license agreement. With regard to Authentic’s amended complaint, the Claims Court also found that the Army’s conduct was not unreasonable, and in line with its obligation under the agreement.

The plaintiffs appealed, challenging dismissal of Ruben as a plaintiff, and the Claims Court’s grant of summary judgment.

With regard to the dismissal of Ruben as a plaintiff, the CAFC ruled that the Claims Court properly dismissed Ruben for lack of standing, as he was not a party to the license agreement, and there is no indication of Ruben as an intended beneficiary of the agreement.

The CAFC then turned to the Claims Court’s grant of summary judgment. The CAFC stated that the license agreement expressly stated that the Army had “sole and absolute discretion” regarding approval of Authentic’s proposed products and marketing materials.

Authentic argued that even if the Army has broad approval discretion under the agreement, that discretion cannot be so broad as to allow the Army to refuse to permit the use of its trademarks “for trademark purposes.” However, the CAFC ruled that the Army’s conduct was not at odd with principles of trademark law. Authentic’s argument appeared to distinguish trademark licenses from other types of contracts, but the CAFC stated that underlying subject matter of the contract is not an issue, and contracting parties are “generally held to the terms of which they bargained.”

The CAFC found Authentic’s argument to be problematic also in that it relies on an outdated model of trademark licensing law, where, at one point, “a trademark’s sole purpose was to identify for consumers the products’ physical source of origin,” and therefore, trademark licensing was “philosophically impossible.” Under the current law, trademark licenses are allowed as long as the trademark owner exercises quality control over the products associated with its trademarks. Here, Army fulfilled its duty of quality control with an approval process.

The CAFC considered Authentic’s arguments and found them unpersuasive, thus affirming the Claims Court’s grant of summary judgment in favor of the government.

Takeaway

- Review carefully the terms of any licensing agreement and negotiate for terms prior to signing. Trademark license agreements are not any different from other types of contracts, and the parties are generally held to the terms of the contracts.

Quality and Quantity of Specification Support in Determining Patent Eligibility

John Kong | March 19, 2021

Simio, LLC v Flexsim Software Products, Inc.

December 29, 2020

Prost, Clevenger, and Stoll

Summary:

In upholding a district court’s finding of patent ineligibility for a computer-based system for object-oriented simulation, the Federal Circuit uses a new “quality and quantity” assessment of the specification’s description of an asserted claim limitation that supposedly supports the claim being directed to an improvement in computer functionality (and not an abstract idea). Here, numerous portions of the specification emphasized an improvement for a user to build object-oriented models for simulation using graphics, without the need to do any programming. This supported the court’s finding that the character of the claim as a whole is directed to an abstract idea – of using graphics instead of programming to create object-oriented simulation models. In contrast to the numerous specification descriptions supporting the abstract idea focus of the patent, one claimed feature that Simio asserted as reflecting an improvement in computer functionality was merely described in just one instance in the specification. This “disparity in both quality and quantity” between the specification support of the abstract idea versus the specification support for the asserted claim feature does not change the claim as a whole as being directed to the abstract idea.

Procedural History:

Simio, LLC sued FlexSim Software Products, Inc. for infringing U.S. Patent No. 8,156,468 (the ‘468 patent). FlexSim moved for judgment on the pleadings under Rule 12(b)(6) for failing to state a claim upon which relief could be granted because the claims of the ‘468 patent are patent ineligible under 35 USC § 101. The district court granted that motion and dismissed the case. The Federal Circuit affirmed.

Background:

Representative claim 1 of the ‘417 patent follows:

A computer-based system for developing simulation models on a physical computing device, the system comprising:

one or more graphical processes;

one or more base objects created from the one or more graphical processes,

wherein a new object is created from a base object of the one or more base objects by a user by assigning the one or more graphical processes to the base object of the one or more base objects;

wherein the new object is implemented in a 3-tier structure comprising:

an object definition, wherein the object definition includes a behavior,

one or more object instances related to the object definition, and

one or more object realizations related to the one or more object instances;

wherein the behavior of the object definition is shared by the one or more object instances and the one or more object realizations; and

an executable process to add a new behavior directly to an object instance of the one or more object instances without changing the object definition and the added new behavior is executed only for that one instance of the object.

Computer-based simulations can be event-oriented, process-oriented, or object-oriented. Earlier object-oriented simulation platforms used programming-based tools that were “largely shunned by practitioners as too complex” according to the ‘468 patent. Use of graphics emerged in the 1980s and 1990s to simplify building simulations, via the advent of Microsoft Windows, better GUIs, and new graphically based tools. Along this graphics trend, the ‘468 patent focuses on making object-oriented simulation easier for users to build simulations using graphics, without any need to write programming code to create new objects.

Decision:

Under Alice step one’s “directed to” inquiry, the court asks “what the patent asserts to be the focus of the claimed advance over the prior art.” To answer this question, the court focuses on the claim language itself, read in light of the specification.

Here, the preamble relates the claim to “developing simulation models,” and the body of the claim recites “one or more graphical processes,” “one or more base objects created from the one or more graphical processes,” and “wherein a new object is created from a base object … by assigning the one or more graphical processes to the base object…” There is also the last limitation (the “executable-process limitation”). Although other limitations exist, Simio did not rely on them for its eligibility arguments.

The court considered these limitations in view of the specification. The ‘468 patent acknowledged that using graphical processes to simplify simulation building has been done since the 1980s and 1990s. And, the ‘468 patent specification states:

“Objects are built using the concepts of object-orientation. Unlike other object-oriented simulation systems, however, the process of building an object in the present invention is simple and completely graphical. There is no need to write programming code to create new objects.” ‘468 patent, column 8, lines 22-26 (8:22-26).

“Unlike existing object-oriented tools that require programming to implement new objects, Simio™ objects can be created with simple graphical process flows that require no programming.” 4:39-42.

“By making object building a much simpler task that can be done by non-programmers, this invention can bring an improved object-oriented modeling approach to a much broader cross-section of users.” 4:47-50.

“The present invention is designed to make it easy for beginning modelers to build their own intelligent objects … Unlike existing object-based tools, no programming is required to add new objects.” 6:50-53.

“In the present invention, a graphical modeling framework is used to support the construction of simulation models designed around basic object-oriented principles.” 8:60-62.

“In the present invention, this logic is defined graphically … In other tools, this logic is written in programming languages such as C++ or Java.” 9:67-10:3.

Taking the claim limitations, read in light of the specification, the court concludes that the key advance is simply using graphics instead of programming to create object-oriented simulations. “Simply applying the already-widespread practice of using graphics instead of programming to the environment of object-oriented simulations is no more than an abstract idea.” “And where, as here, ‘the abstract idea tracks the claim language and accurately captures what the patent asserts to be the focus of the claimed advance …, characterizing the claim as being directed to an abstract idea is appropriate.’”

Simio argued that claim 1 “improves on the functionality of prior simulation systems through the use of graphical or process modeling flowcharts with no programming code requited.” However, an improvement emphasizing “no programming code required” is an improvement for a user – not an improvement in computer functionality. An improvement in a user’s experience (not having to write programming code) while using a computer application does not transform the claims to be directed to an improvement in computer functionality.

Simio also argued that claim 1 improves a computer’s functionality “by employing a new way of customized simulation modeling with improved processing speed.” However, improved speed or efficiency here is not that of the computer, but rather that of the user’s ability to build or process simulation models faster using graphics instead of programming. In other words, the improved speed or efficiency is not that of computer functionality, but rather, a result of performing the abstract idea with well-known structure (a computer) by a user.

Simio finally argued that the last limitation, the executable-process limitation reflects an improvement to computer functionality. It is with regard to this last argument that the court introduces a new “quality and quantity” assessment of the specification. In particular, the court noted that “this limitation does not, by itself, change the claim’s ‘character as a whole’ from one directed to an abstract idea to one that’s not.” As support of this assessment of the claim’s “character as a whole,” the court cited to at least five instances of the specification emphasizing graphical simulation modeling making model building easier without any programming, in contrast to a single instance of the specification describing the executable process limitation:

Compare, e.g., ’468 patent col. 4 ll. 29–42 (noting that “the present invention makes model building dramatically easier,” as “Simio™ objects” can be created with graphics, requiring no programming), and id. at col. 4 ll. 47–50 (describing “this invention” as one that makes object-building simpler, in that it “can be done by non-programmers”), and id. at col. 6 ll. 50–53 (describing “[t]he present invention” as one requiring no programming to build objects), and id. at col. 8 ll. 23–26 (“Unlike other object-oriented simulation systems, however, the process of building an object in the present invention is simple and completely graphical. There is no need to write programming code to create new objects.”), and id. at col. 8 ll. 60–62 (“In the present invention, a graphical modeling frame-work is used to support the construction of simulation models designed around basic object-oriented principles.”), with col. 15 l. 45–col. 16 l. 6 (describing the executable-process limitation). This disparity—in both quality and quantity—between how the specification treats the abstract idea and how it treats the executable-process limitation suggests that the former remains the claim’s focus.

Even Simio’s own characterization of the executable-process limitation closely aligns with the abstract idea: (a) that the limitation reflects that “a new behavior can be added to one instance of a simulated object without the need for programming” and (b) that the limitation reflects an “executable process that applies the graphical process to the object (i.e., by applying only to the object instance not to the object definition).” Although this is more specific than the general abstract idea of applying graphics to object-oriented simulation, this merely repeats the above-noted focus of the patent on applying graphical processes to objects and without the need for programming. As such, this executable-process limitation does not shift the claim’s focus away from the abstract idea.

At Alice step two, Simio argued that the executable-process limitation provides an inventive concept. However, during oral arguments, Simio conceded that the functionality reflected in the executable-process limitation was conventional or known in object-oriented programming. In particular, implementing the executable process’s functionality through programming was conventional or known. Doing so through graphics does not confer an inventive concept. What Simio relies on is just the abstract idea itself – use of graphics in object-oriented simulation. Reliance on the abstract idea itself cannot supply the inventive concept that renders the invention “significantly more” than that abstract idea.

Even if the use of graphics instead of programming to create object-oriented simulations is new, a claim directed to a new abstract idea is still an abstract idea – lacking any meaningful application of the abstract idea sufficient to constitute an inventive concept to save the claim’s eligibility.

Takeaways:

- This case serves a good reminder of the importance of proper specification drafting to address 101 issues such as these. An “improvement” that can be deemed an abstract idea (e.g., use graphics instead of programming) will not help with patent eligibility. The focus of an “improvement” to support patent eligibility must be technological (e.g., in order to use graphics instead of programming in object-oriented simulation modeling, this new xyz procedure/data structure/component replaces the programming interface previously required…). “Technological” is not to be confused with being “technical” – which could mean just disclosing more details, albeit abstract idea type of details that will not help with patent eligibility. Here, even a “new” abstract idea does not diminish the claim still being “directed to” that abstract idea, nor rise to the level of an inventive concept. Improving user experience is not technological. Improving a user’s speed and efficiency is not technological. Improving computer functionality by increasing its processing speed and efficiency could be sufficiently technological IF the specification explains HOW. Along the lines of Enfish, perhaps new data structures to handle a new interface between graphical input and object definitions may be a technological improvement, again, IF the specification explains HOW (and if that “HOW” is claimed). In my lectures, a Problem-Solution-Link methodology for specification drafting helps to survive patent eligibility. Please contact me if you have specification drafting questions.

- This case also serves as a good reminder to avoid absolute statements such as “the present invention is …” or “the invention is… .” There is caselaw using such statements to limit claim interpretation. Here, it was used to ascertain the focus of the claims for the “directed to” inquiry of Alice step one. The more preferrable approach is the use of more general statements, such as “at least one benefit/advantage/improvement of the new xyz feature is to replace the previous programming interface with a graphical interface to streamline user input into object definitions…”

- This decision’s “quality and quantity” assessment of the specification’s focus on the executable-process limitation provides a new lesson. Whatever is the claim limitation intended to “reflect” an improvement in technology, there should be sufficient specification support for that claim limitation – in quality and quantity – for achieving that technological improvement. Stated differently, the key features of the invention must not only be recited in the claim, but also, be described in the specification to achieve the technological improvement, with an explanation as to why and how.

- This is yet another unfortunate case putting the Federal Circuit’s imprimatur on the flawed standard to find the “the focus of the claimed advance over the prior art” in Alice step one, albeit not as unfortunate as Chamberlain v Techtronic (certiorari denied) or American Axle v Neapco (still pending certiorari). In another lecture, I explain why the “claimed advance” standard is problematic and why it contravenes Supreme Court precedent. Briefly, the claimed advance standard is like the “gist” or “heart” of the invention standard of old that was nixed. In Aro Mfg. Co. v. Convertible Top Replacement Co., the Supreme Court stated that “there is no legally recognizable or protected ‘essential’ element, ‘gist’ or ‘heart’ of the invention in a combination patent.” In §§102 and 103 issues, the Federal Circuit said distilling an invention down to its “gist” or “thrust” disregards the claim “as a whole” requirement. Likewise, stripping the claim of all its known features down to its “claimed advance over the prior art” is also contradictory to the same requirement to consider the claim as a whole under section 101. Moreover, the claimed advance standard contravenes the Supreme Court’s warnings in Diamond v Diehr that “[i]t is inappropriate to dissect the claims into old and new elements and then to ignore the presence of the old elements in the analysis. … [and] [t]he ‘novelty’ of any element or steps in a process, or even of the process itself, is of no relevance in determining whether the subject matter of a claim falls within the 101 categories of possibly patentable subject matter.” Furthermore, the origins of the claimed advance standard have not been vetted. Originally, the focus was on finding a practical application of an abstract idea in the claim. This search for a practical application morphed, without proper legal support, into today’s claimed advance focus in Alice step one. Interestingly enough, since the 2019 PEG, the USPTO has not substantively revised its subject matter eligibility guidelines to incorporate any of the recent “claimed advance” Federal Circuit decisions.

Tags: 35 U.S.C. § 101 > abstract idea > patent eligibility > specification drafting

Make Sure Patent Claims Do Not Contain an Impossibility

Bo Xiao | March 12, 2021

Synchronoss Technologies, Inc., v. Dropbox, Inc.

February 12, 2021

PROST, REYNA and TARANTO

Summary

Synchronoss Technologies appealed the district court’s decisions that all asserted claims relating to synchronizing data across multiple devices are either invalid or not infringed. The Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s judgments of invalidity under 35 U.S.C. § 112, paragraph 2, with respect to certain asserted claims due to indefiniteness. The Federal Circuit also found no error in the district court’s conclusion that Dropbox does not directly infringe by “using” the claimed system under § 271(a). Thus, the Federal Circuit affirmed on non-infringement.

Background

Synchronoss sued Dropbox for infringement of three patents, 6,757,696 (“’696 patent”), 7,587,446 (“’446 patent”), and U.S. Patent Nos. 6,671,757 (“’757 patent”), all drawn to technology for synchronizing data across multiple devices.

The ’446 patent discloses a “method for transferring media data to a network coupled apparatus.” The indefinite argument of Dropbox targets on the asserted claims that require “generating a [single] digital media file” that itself “comprises a directory of digital media files.” Synchronoss’s expert conceded that “a digital media file cannot contain a directory of digital media files.” But Synchronoss argued that a person of ordinary skill in the art “would have been reasonably certain that the asserted ’446 patent claims require a digital media that is a part of a directory because a file cannot contain a directory.” The district court rejected the argument as “an improper attempt to redraft the claims” and concluded that all asserted claims of the ’446 patent are indefinite.

The ’696 patent discloses a synchronization agent management server connected to a plurality of synchronization agents via the Internet. The asserted claims of the ‘696 patent all include the following six terms, “user identifier module,” “authentication module identifying a user coupled to the synchronization system,” “user authenticator module,” “user login authenticator,” “user data flow controller,” and “transaction identifier module.” The district court concluded that all claims in the ’696 patent are invalid as indefinite. The decision leaned on the technical expert’s testimony that all six terms are functional claim terms. The specification failed to describe any specific structure for carrying out the respective functions.

The asserted claim 1 of ‘757 patent recites “a system for synchronizing data between a first system and a second system, comprising …” The district court found that hardware-related terms appear in all asserted claims of ‘757 patent. The hardware-related terms include “system,” “device,” and “apparatus,” all that means the asserted claims could not cover software without hardware. Dropbox argued that it distributed the accused software with no hardware. The district court granted summary judgment of non-infringement in favor of Dropbox.

Discussion

i. The ‘446 Patent – Indefiniteness

The Federal Circuit noted that the claims were held indefinite in circumstances where the asserted claims of the ’446 patent are nonsensical and require an impossibility—that the digital media file contains a directory of digital media files. As a matter of law under § 112, paragraph 2, the claims are required to particularly point out and distinctly claim the invention. “The primary purpose of this requirement of definiteness of claim language is to ensure that the scope of the claims is clear so the public is informed of the boundaries of what constitutes infringement of the patent.” (MPEP 2173)

Synchronoss argued that a person of ordinary skill would read the specification to interpret the meaning of the media file. However, the Federal Circuit rejected the argument since Synchronoss’s proposal would require rewriting the claims and also stated that “it is not our function to rewrite claims to preserve their validity.”

ii. The ‘696 Patent – Indefiniteness

The ‘696 patent was focused on whether the claims at issue invoke § 112, paragraph 6. The Federal Circuit applied a two-step process for construing the term, 1. identify the claimed function; 2. determine whether sufficient structure is disclosed in the specification that corresponds to the claimed function.

However, the asserted claims were found not to detail what a user identifier module consists of or how it operates. The specification fails to disclose an “adequate” corresponding structure that a person of ordinary skill in the art would be able to recognize and associate with the corresponding function in the claim. The Federal Circuit held that the term “user identifier module” is indefinite and affirmed the district court’s decision that asserted claims are invalid.

iii. The ‘757 Patent – Infringement

The ‘757 patent is the only one focused on the infringement issue. Synchronoss argued that the asserted claims recite hardware not as a claim limitation but merely as a reference to the “location for the software.” However, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s founding that the hardware term limited the asserted claims’ scope.

The Federal Circuit explained that “Supplying the software for the customer to use is not the same as using the system.” Dropbox only provides software to its customer but no corresponding hardware. Thus, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s summary judgment of non-infringement.

Takeaway

- Make sure patent claims do not contain an impossibility

- Supplying software alone does not infringe claims directed to hardware.

- “Adequate” structures in the specification are required to support the functional terms in the claims.