Tailored Advertising Claims Are Invalidated Due to Lack of Improvements to Computer Functionality

Bo Xiao | June 8, 2021

Free Stream Media Corp., DBA Samba Tv, V. Alphonso Inc., Ashish Chordia, Lampros Kalampoukas, Raghu Kodige

Decided on May 11, 2021

Before DYK, REYNA, and HUGHES. Opinion by REYNA.

Summary

The Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s decision and found that the asserted claims directed to tailored advertising were patent ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

Background

Free Stream sued Alphonso for infringement of its US patents No. 9,026,668 (“the ’668 patent”) and No. 9,386,356 (“the ’356 patent”). The patents describe a system sending tailored advertisements to a mobile phone user based on data gathered from the user’s television. Claim 1 and 10 were involved in the alleged infringement. Free Stream conceded claims 1 and 10 are similar. Listed below is claim 1.

1. A system comprising:

a television to generate a fingerprint data;

a relevancy-matching server to:

match primary data generated from the fingerprint data with targeted data, based on a relevancy factor, and

search a storage for the targeted data;

wherein the primary data is any one of a content identification data and a content identification history;

a mobile device capable of being associated with the television to:

process an embedded object,

constrain an executable environment in a security sandbox, and

execute a sandboxed application in the executable environment; and

a content identification server to:

process the fingerprint data from the television, and

communicate the primary data from the fingerprint data to any of a number of devices with an access to an identification data of at least one of the television and an automatic content identification service of the television.

The asserted claims of ‘356 patent includes three main components: (1) a television (e.g., a smart TV) or a networked device ; (2) a mobile device or a client device ; and (3) a relevancy matching server and a content identification server. The television is a network device collecting primary data, which can consist of program information, location, weather information, or identification information. The mobile phone is a client device that may be smartphones, computers, or other hardware showing advertisements. The client device includes a security sandbox, which is a security mechanism for separating running programs. Finally, the servers use primary data from the networked device to select advertisements or other targeted data based on a relevancy factor associated with the user.

Alphonso argued that the asserted claims are patent ineligible under § 101 because they are directed to the abstract idea of tailored advertising. But Free Stream characterized the claims as directed to a specific improvement of delivering relevant content (e.g., targeted advertising) by bypassing the conventional “security sandbox” separating the mobile phone from the television.

The district court rejected Alphonso’s argument and applied step one of the Alice test to conclude that the asserted claims are not directed to an abstract idea. The district court found that the ’356 patent “describes systems and methods for addressing barriers to certain types of information exchange between various technological devices, e.g., a television and a smartphone or tablet being used in the same place at the same time.”

Discussion

The Federal Circuit agreed with Alphonso’s contention that the district court erred in concluding that the ’356 patent is not directed to patent-ineligible subject matter. Claims 1 and 10 were reviewed by the Federal Circuit as being directed to (1) gathering information about television users’ viewing habits; (2) matching the information with other content (i.e., targeted advertisements) based on relevancy to the television viewer; and (3) sending that content to a second device.

Free Stream contended that claim 1 is “specifically directed to a system wherein a television and a mobile device are intermediated by a content identification server and relevancy-matching server that can deliver to a ‘sandboxed’ mobile device targeted data based on content known to have been displayed on the television, despite the barriers to communication imposed by the sandbox.” Free Stream also asserted that its invention allows devices on the same network to communicate where such devices were previously unable to do so, namely bypassing the sandbox security.

The Federal Circuit, however, noted that the specification does not provide for any other mechanism that can be used to bypass the security sandbox other than “through a cross site scripting technique, an appended header, a same origin policy exception, and/or an other mode of bypassing

a number of access controls of the security sandbox.” Also, the Federal Circuit pointed out that the asserted claims only state the mechanism used to achieve the bypassing communication but not at all describe how that result is achieved.

Further, the Federal Circuit went on to note that “even assuming the specification sufficiently discloses how the sandbox is overcome, the asserted claims nonetheless do not recite an improvement in computer functionality.” The asserted claims do not incorporate any such limitations of bypassing the sandbox. The Federal Circuit determined that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of “targeted advertising.”

The Federal Circuit further reached Step 2 because the district court concluded that the claims were not directed to an abstract idea at Step 1. Free Stream argued that the claims of the ’356 patent “specify the components or methods that permit the television and mobile device to operate in [an] unconventional manner, including the use of fingerprinting, a content identification server, a relevancy-matching server, and bypassing the mobile device security sandbox.”

The argument on Step 2 was also directed around bypassing sandbox security. The Federal Circuit explained that the security sandbox may limit access to the network, but the claimed invention simply seeks to undo that by “working around the existing constraints of the conventional functioning of television and mobile devices.” It was concluded that “such a ‘work around’ or ‘bypassing’ of a client device’s sandbox security does nothing more than describe the abstract idea of providing targeted content to a client device.” The Federal Circuit emphasized that “an abstract idea is not patentable if it does not provide an inventive solution to a problem in implementing the idea.” Finally, the Federal Circuit found that the asserted claims simply utilized generic computing components arranged in a conventional manner but failed to embody an “inventive solution to a problem.”

Takeaway

- An abstract idea is not patentable if it does not provide an inventive solution to a problem in implementing the idea.

- The “work-around” does not add more features that give rise to a Step 2 “inventive concept.”

Lying in a Deposition – Never a Good Policy

Fumika Ogawa | June 2, 2021

Cap Export, LLC v. Zinus, Inc.

Decided on May 5, 2021

Summary

Rule 60(b)(3) relieves a patent challenger of a final judgment entered in favor of a patentee where the patent challenger with due diligence could not discover a later-revealed fraud committed by the patentee during the underlying litigation in which the deposed patentee’s witness lied to conceal his knowledge of on-sale prior art determined to be highly material to the validity of the patent.

Details

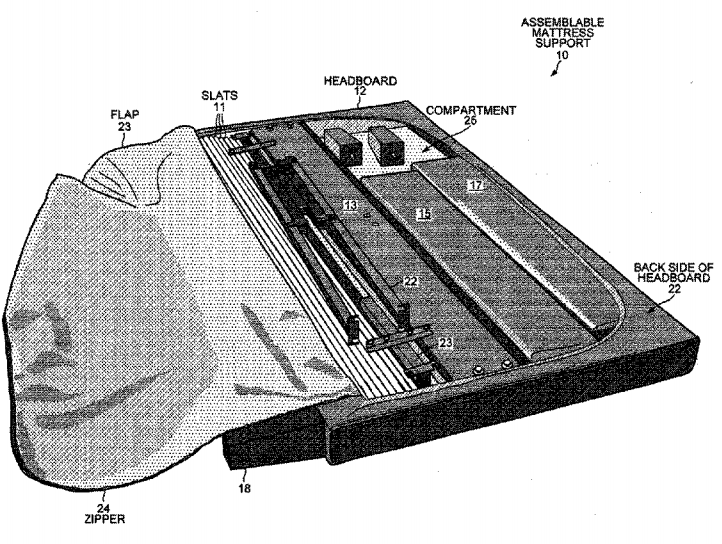

Zinus owns U.S. Patent No. 8,931,123 (“the ’123 patent”) entitled “Assemblable mattress support whose components fit inside the headboard.” The invention allows for packing various components of a bed into its headboard compartment for easy shipping in a compact state. The concept may be seen in one of the ‘123 patent figures:

The application that resulted in the ‘123 patent was filed in September 2013.

In 2016, Cap Export, LLC (“Cap Export”) sought declaratory judgment of invalidity and noninfringement of the ‘123 patent in the Central District of California. The lawsuit eventually resulted in the district court upholding the validity of the ‘123 patent claims as not anticipated or obvious over all prior art references considered. The final judgment stipulated and entered in favor of Zinus included payment of $1.1 million in damages to Zinus, and a permanent injunction against Cap Export[1]. Particularly relevant to the present case is the fact that in the course of the lawsuit, Cap Export deposed Colin Lawrie, Zinus’s president and expert witness, as to his knowledge of various prior art items.

In 2019, Zinus sued another company for infringement of the ‘123 patent. This second lawsuit prompted Cap Export to learn that Zinus’s group company had bought hundreds of beds manufactured by a foreign company which apparently had a bed-in-a-headboard feature, before the filing date of the ‘123 patent. Colin Lawrie, the aforementioned Zinus’s president, appears to be involved in this transaction as the purchase invoice was signed by Lawrie himself.

Cap Export then timely filed a Rule 60(b)(3) motion for relief from the final judgment, alleging that Lawrie during the previous deposition lied to Cap Export’s counsel. Some questions and answers highlighted in the case include:

Q. Prior to September 2013 had you ever seen a bed that was shipped disassembled in one box?

A. No.

Q. Not even—I’m not talking about everything stored in the headboard, I’m just saying one box.

A. No, I don’t think I have.

In the Rule 60(b)(3) proceeding, Lawrie admitted that his deposition testimony was “literally incorrect” while denying intentional falsity because he had misunderstood the question to refer to a bed contained “in one box with all of the components in the headboard,” rather than a bed contained “in one box” (where most laypersons should know of the latter, if not the former).

The district court was not convinced, pointing to the fact that Cap Export’s counsel had rephrased the question to distinguish the two concepts. Also, emails were discovered showing repeated sales of the beds at issue to Zinus’s family companies, the record which Zinus admitted had been in its possession throughout the underlying litigation.

The district court set aside the final judgement under Rule 60(b)(3), finding that the purchased beds were “functionally identical in design” to the ’123 patent claims, and that Lawrie’s repeated denials of his knowledge of such beds amounted to affirmative misrepresentations. Zinus appealed.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed.

FRCP Rule 60(b)(3)

Rule 60(b)(3) relieves a losing party of a final judgment where an opposing party commits “fraud … , misrepresentation, or misconduct.” The Ninth Circuit applies an additional requirement that the fraud not be discoverable through “due diligence”[2]. A movant must prove by clear and convincing evidence that the opposing party has obtained the verdict in its favor through fraudulent conduct which “prevented the losing party from fully and fairly presenting the defense.” Since the issue is procedural, the Federal Circuit follows regional circuit law and reviews the district court decision for abuse of discretion.

Due Diligence in Discovering Fraud

Zinus’s main contention was that the due diligence requirement is not satisfied, arguing that the key evidence would have been discovered had Cap Export’s counsel taken more rigorous discovery measures[3] specific to patent litigation.

The Federal Circuit disagreed, finding that due diligence in discovering fraud is not about the lawyers’ lacking a requisite standard of care, but rather, the question is “whether a reasonable company in Cap Export’s position should have had reason to suspect the fraud … and, if so, took reasonable steps to investigate the fraud.”

Here, Cap Export met the requirement because there was no reason to suspect the fraud in the first place. Lawrie’s repeated denials in the deposition testimony, combined with the impossibility to reach the concealed evidence despite numerous search efforts by Cap Export and the general unavailability of such evidence, forestalled an initial suspicion of fraud which would otherwise call for further inquiry into the possible misconduct.

Opponent’s Fraud Preventing Fair and Full Defense

The Federal Circuit also found that the district court had not abuse its discretion in judging other parts of Rule 60(b)(3) jurisprudence.

As to the existence of fraud, the Federal Circuit approved the district court’s finding of affirmative misrepresentations. There is no clear error where the district court rejected Lawrie’s explanation that the false testimony arose from misunderstanding and was unintentional, which lacks credibility given the fact that the deposition occurred within a few years from the sales at issue.

As to the frustration of fairness and fullness, the Federal Circuit noted that Rule 60(b)(3) standard does not require showing that the result would have been different but for the fraudulently withheld information, but showing the evidence’s “likely worth” is sufficient to establish the harm. As such, the concealed prior art does not have to “qualify as invalidating prior art,” but being “highly material” suffices.

The Federal Circuit endorsed the district court’s judgment that the concealed evidence “would have been material” and its unavailability to Cap Export prevented it from fully and fairly presenting its case. The determination rests on the underlying factual findings that the on-sale prior art is “functionally identical in design” to the ‘123 patent claims, and that without the misrepresentations, the evidence would have been considered by the court in its obvious and anticipation analysis.

The Opinion’s closing remarks appear to suggest an implication of the procedural rules such as Rule 60(b)(3) in allowing the patent system to achieve its core purpose of serving the public interest. Legitimacy of patents is preserved by warding off fraudulent conduct in proceedings before the court, the establishment which works only where parties give entire information for a full and fair determination of their controversy.

Takeaway

- A favorable verdict procured through fraud will be vacated under Rule 60(b)(3).

- Due diligence requirement under Rule 60(b)(3) is unique to the Ninth Circuit. In cases involving the patentee’s knowledge about prior art, reasonableness in the patent challenger’s discovery and investigation tactics, even if they didn’t expose a lie, likely satisfies this additional requirement.

- To establish the evidentiary value of the concealed prior art in a Rule 60(b)(3) motion, a showing that the information is “highly material” to presenting the movant’s case, if not “invalidating” the patent, would be sufficient.

- In the present case, the second lawsuit filed by the patentee (i.e., the lying party) led to the discovery of its own fraud. What could the patent challenger have done to safeguard against the patentee’s lies in the first lawsuit? Perhaps taking patent-specific standard discovery measures such as those noted at footnote 3 might help. Watch out for a patentee’s past transactions involving products manufactured by a third party, which might be “highly material” on-sale prior art simply because of its functional or design similarity to the patent claims.

- After a final judgment is entered, a losing party may benefit from monitoring the opponent’s litigation activity involving the patent at issue, which might lead to discovery of previously unknown information, allowing for a potential Rule 60(b)(3) relief.

[1] And a third-party defendant added during the litigation. The parties on Cap Export’s side are referred to collectively as Cap Export.

[2] The Federal Circuit notes that the diligence requirement is at odds with the plain text of Rule 60(b)(3) and does not appear to be adopted in other regional courts of appeals. Compare Rule 60(b)(2), which states that “newly discovered evidence that, with reasonable diligence, could not have been discovered in time to move for a new trial.”

[3] Such as “[to] specifically seek prior art [in a written discovery request]; … [to] depose the inventor of the ’123 patent; and [to take] a deposition of Lawrie … [specifically] under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 30(b)(6).”

Inventors’ Agreements will not protect a former employer from the inventors’ future related work

Michael Caridi | May 27, 2021

Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. v. International Trade Commission, 10X Genomics Inc.

Decided on April 29, 2021

Before Taranto, Chen and Stoll. Opinion by Taranto.

Summary:

Bio-Rad attempted to assert that language in inventors’ agreements which were signed by two of the named inventors in the patents asserted against Bio-Rad made the patents their intellectual property by being subject to assignment. The CAFC disagreed noting that the agreements were too general is scope as asserted and 10X had failed to assert an earlier conception date.

Details

- Background

10X Genomics Inc. filed a complaint against Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. with the International Trade Commission, alleging that Bio-Rad’s importation and sale of microfluidic systems and components used for gene sequencing or related analyses violated section 337 of the Tariff Act of 1930, 19 U.S.C. § 1337.

The ITC found that Bio-Rad infringed the patent claims at issue and also that 10X practiced the claims, the latter fact satisfying the requirement of a domestic industry relating to the articles protected by the patent. Bio-Rad argued on appeal that the Commission erred in finding that Bio-Rad infringes the asserted claims of the patents, in finding that 10X’s domestic products practice the asserted claims of the ’530 patent, and in rejecting Bio-Rad’s indefiniteness challenge to the asserted claims of the ’530 patent. The CAFC disagreed and affirmed the Commission. These aspects of the appeal are not the subject of this paper.

In addition, the ITC rejected Bio-Rad’s defense that it could not be liable for infringement because it co-owned the asserted 10X patents under assignment provisions that two of the named inventors signed when they were employees of Bio-Rad (and its predecessor), even though the inventions claimed were not made until after the employment.

Regarding the timeline of invents of the work of the two inventors, around mid-2010, the two named inventors of the 10X patents—Dr. Hindson and Dr. Saxonov—were working for a company called QuantaLife, Inc., which Dr. Hindson had co-founded. Each of them signed an agreement (Dr. Hindson in 2009, Dr. Saxonov in 2010) that provided, as relevant here:

(a) Employee agrees to disclose promptly to the Company the full details of any and all ideas, processes, recipes, trademarks and service marks, works, inventions, discoveries, marketing and business ideas, and improvements or enhancements to any of the foregoing (“IP”), that Employee conceives, develops or creates alone or with the aid of others during the term of Employee’s employment with the Company . . . .

(b) Employee shall assign to the Company, with-out further consideration, Employee’s entire right to any IP described in the preceding subsection, which shall be the sole and exclusive property of the Company whether or not patentable.

In 2011, Bio-Rad acquired QuantaLife, and Drs. Hindson and Saxonov became Bio-Rad employees. In October of that year, they each signed an agreement that provided, as relevant here:

All inventions (including new contributions, improvements, designs, developments, ideas, discoveries, copyrightable material, or trade secrets) which I may solely or jointly conceive, develop or reduce to practice during the period of my employment by Bio-Rad shall be assigned to Bio-Rad.

Drs. Hindson and Saxonov left Bio-Rad in April 2012, and together they formed 10X in July 2012. By August 2012, 10X filed the first of several provisional patent applications that focused on using microcapsules in capsule partitions or droplet partition. By January 2013, the 10X inventors had conceived of a different architecture: “gel bead in emulsion” (GEM). The GEM architecture involves “part-tioning nucleic acids, DNA or RNA, in droplets together with gel beads that are used to deliver the barcodes into the droplet,” where the “barcodes are released from the gel beads using a stimulus.” The asserted 10X patent claims all involve this architecture. The CAFC found that the common core of the inventions in the asserted 10X patents is the use of gel beads with releasably attached oligonucleotide barcode molecules as a system for delivery of barcodes to nucleic acid segments.

After 10X began selling its products, including the GemCode and Chromium products, Bio-Rad released its own ddSEQ™ system, whose ordinary use, 10X alleges, practices its patents. The ddSEQ system uses oligonucleotide molecules that are attached to a gel bead and can be released from the bead via a stimulus.

- Opinion

On appeal, Bio-Rad renewed its argument, made as a defense to infringement, that it co-owns the three assert-ed patents based on the assignment provisions in the employment contracts signed by Drs. Hindson and Sax-onov. The CAFC noted that it is undisputed that, if Bio-Rad is a co-owner, it cannot be an infringer, per 35 U.S.C. § 262 (“[E]ach of the joint owners of a patent may make, use, offer to sell, or sell the patented invention . . . without the consent of and without accounting to the other owners.”). However, co-ownership itself was disputed.

The CAFC first noted that Bio-Rad did not present an alternative conception date (earlier than January 2013), and it lost the opportunity to argue conception of certain claim elements while Drs. Hindson and Saxonov were at QuantaLife.

The Court reasoned that Bio-Rad has furnished no persuasive basis for disturbing the Commission’s conclusion that the assignment provisions do not apply to a signatory’s ideas developed during the employment (with Bio-Rad or QuantaLife) solely because the ideas ended up contributing to a post-employment patentable invention in a way that supports co-inventorship of that eventual invention.

Examining the employee agreements, the CAFC found that the assignment provisions are limited temporally. The assignment provision of the QuantaLife agreement reaches only a “right to any IP described in the preceding section,” and the preceding (disclosure-duty) section is limited to IP “that Employee conceives, develops or creates alone or with the aid of others during the term of Employee’s employment with the Company,” before adding a limitation, stating: “All inventions . . . which I may solely or jointly conceive, develop, or reduce to practice during the period of my employment by Bio-Rad shall be assigned to Bio-Rad.”. Based thereon, the Court concluded that the most straightforward interpretation is that the assignment duty is limited to subject matter that itself could be protected as intellectual property before the termination of employment.

The Court went on to note that Bio-Rad did not argue or demonstrate, that a person’s work, just because it might one day turn out to contribute significantly to a later patentable invention and make the person a co-inventor, is itself protectible intellectual property before the patentable invention is made. Specifically, the CAFC stated:

Such work is merely one component of “possible intellectual property.” Bio-Rad Reply Br. at 3. In the case of a patent, it may be a step toward the potential ultimate existence of the only pertinent intellectual property, namely, a completed “invention,” but the pertinent intellectual property does not exist until at least conception of that invention. See, e.g., REG Synthetic Fuels, LLC v. Neste Oil Oyj, 841 F.3d 954, 958 (Fed. Cir. 2016); Dawson v. Dawson, 710 F.3d 1347, 1353 (Fed. Cir. 2013); Burroughs Wellcome Co. v. Barr Labs., Inc., 40 F.3d 1223, 1227–28 (Fed. Cir. 1994).

The panel reviewed the current fact pattern in light of previous decisions on the issue of inventor’s employment agreements. Of note, regarding the FilmTec case (FilmTec Corp. v Hydranautics, 982 F.2d 1546, 1548 (Fed. Cir. 1992)) cited by Bio-Rad involved language of an agreement, and language of the statutory command embodied in the agreement, that expressly assigned ownership to the United States of certain inventions as long as they were “conceived” during performance of government-supported work under a contract. The panel noted that in the Filmtec case the Court had examined the claimed invention, namely, a composition conceived during the term of the agreement, where conception meant the “‘formation in the mind of the inventor, of a definite and permanent idea of the complete and operative invention, as it is hereafter to be applied in practice.’” Id. at 1551–52 (quoting Hybritech Inc. v. Monoclonal Antibodies, Inc., 802 F.2d 1367, 1376 (Fed. Cir. 1986)).

We noted that the inventor, continuing to work on the invention after the agreement ended, added certain “narrow performance limitations in the claims.” See id. at 1553. But we treated the performance limitations as not adding anything of inventive significance because they were mere “refine[ments]” to the invention already conceived during the term of the agreement. See id. at 1552–53. We held the claimed inventions to have been conceived during the agreement—something that Bio-Rad accepts is not true here. We did not deem a mere joint inventor’s contribution to a post-agreement conception sufficient. (Emphasis added).

The CAFC additionally reviewed the Stanford case (Bd. of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior Univ. v. Roche Molecular Sys., Inc., 583 F.3d 832, 837 (Fed. Cir. 2009), aff’d on different grounds, 563 U.S. 776 (2011)), also relied on by Bio-Rad, involved quite different contract language from the language at issue. The case involved a Stanford employee who was spending time at Cetus in order to learn important new research techniques; as part of the arrangement, the Stanford employee signed an agreement with Cetus committing to assign to Cetus his “right, title, and interest” in the ideas, inventions, and improvements he conceived or made “as a consequence of” his work at Cetus. The CAFC noted that the Stanford case was not a former-employee case and the language at issue in Stanford did not contain the temporal limitation set forth in the agreements at issue. The Court concluded by noting that the agreement at issue here did not contain the broad “as a consequence of” language at issue in Stanford.

The Court also examined the relevant aspects of the governing law of California which provides a confirmatory reason not to read the assignment provision at issue here more broadly. California law recognizes significant policy constraints on employer agreements that restrain former employees in the practice of their profession, including agreements that require assignment of rights in post-employment inventions. The Court noted that substantial questions about compliance with that policy would be raised by an employer-employee agreement under which particular subject matter’s coverage by an assignment provision could not be determined at the time of employment, but depended on an unknown range of contingent future work, after the employment ended, to which the subject matter might sufficiently contribute. The reasons behind the policy being that such an agreement might deter a former employee from pursuing future work related to the subject matter and might deter a future employer from hiring that individual to work in the area. The CAFC concluded that the contract language at issue does not demand a reading that would test the California-law constraints and they would not “test those constraints here by adopting a broader reading of the contract language than the straightforward reading we have identified.”

Finally, Bio-Rad had argued that Drs. Hindson and Saxonov conceived of key aspects of the claimed inventions, if not the entirety of the claims, at QuantaLife/Bio-Rad. The Commission had determined that many of these “ideas” are at a level of generality that cannot support joint inventorship or (sometimes and) involve nothing more than elements in the already-published prior art. Specifically, Bio-Rad contended that at least three ideas developed at QuantaLife were not publicly known in the prior art at the time Drs. Hindson and Saxonov were working on them: tagging droplets to track a sample-reagent reaction complex, using double-junction microfluidics to combine sample and reagent, and using oligonucleotides as bar-codes to tag single cells within droplets. After analysis of these concepts, the Court found that these contentions, by their terms, look to a time long before the January 2013 conception date for the inventions at issue and Bio-Rad did not deny that these ideas were in the published prior art by the time of the conception of the inventions at issue or that they were, by then, readily available to the co-inventors on the patents involved. Hence, the Court concluded that the contentions are insufficient to establish co-inventorship.

Specifically, the Court found that to accept Bio-Rad’s contention after giving the required deference to the Commission’s factual (and, in one instance, procedural) rulings would require that they find joint inventorship simply because Drs. Hindson and Saxonov, while at Bio-Rad (or QuantaLife), were working on the overall, known problem—how to tag small DNA segments in microfluidics using droplets—that was the subject of widespread work in the art.

- Decision

The CAFC concluded that Bio-Rad had not demonstrated proper ownership of “ideas” as comported to be assigned to them by the two inventors employment agreements. The general concepts relied upon by Bio-Rad were insufficient as Bio-Rad had failed to assert an earlier conception date. As such, the Court affirmed the Commission’s ruling.

Take away

- Broad language in an employment agreement assigning rights to inventions will not suffice to protect an entity from future work performed by the employees at a different entity.

- Employee agreements assigning rights to inventions conceived while employed need to be structured such that they are clear as to what is conceived is considered the property of the entity. The entity should take steps to clarify “conception” during employment to provide evidence thereof.

An Improvement in Computational Accuracy Is Not a Technological Improvement

Andrew Melick | May 20, 2021

In Re: Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University

Decided on March 25, 2021

Prost, Lourie and Reyna. Opinion by Reyna.

Summary:

This case is an appeal from a PTAB decision that affirmed the Examiner’s rejection of the claims on the grounds that they involve patent ineligible subject matter. Leland Stanford Junior University’s patent to computerized statistical methods for determining haplotype phase were held by the CAFC to be to an abstract idea directed to the use of mathematical calculations and statistical modeling and that the claims lack an inventive concept that transforms the abstract idea into patent eligible subject matter. Thus, the CAFC affirmed the rejection on the grounds that the claims are to patent ineligible subject matter.

Details:

Leland Stanford Junior University’s (“Stanford”) patent application is to methods for determining haplotype phase which provides an indication of the parent from whom a gene has been inherited. The application discloses methods for inferring haplotype phase in a collection of unrelated individuals. The methods involve using a statistical tool called a hidden Markov model (“HMM”). The application uses a statistical model called PHASE-EM which allegedly operates more efficiently and accurately than the prior art PHASE model. The PHASE-EM uses a particular algorithm to predict haplotype phase.

Representative claim 1 recites:

1. A computerized method for inferring haplotype phase in a collection of unrelated individuals, comprising:

receiving genotype data describing human genotypes for a plurality of individuals and storing the genotype data on a memory of a computer system;

imputing an initial haplotype phase for each individual in the plurality of individuals based on a statistical model and storing the initial haplotype phase for each individual in the plurality of individuals on a computer system comprising a processor a memory;

building a data structure describing a Hidden Markov Model, where the data structure contains:

a set of imputed haplotype phases comprising the imputed initial haplotype phases for each individual in the plurality of individuals;

a set of parameters comprising local recombination rates and mutation rates;

wherein any change to the set of imputed haplotype phases contained within the data structure automatically results in re-computation of the set of parameters comprising local recombination rates and mutation rates contained within the data structure;

repeatedly randomly modifying at least one of the imputed initial haplotype phases in the set of imputed haplotype phases to automatically re-compute a new set of parameters comprising local recombination rates and mutation rates that are stored within the data structure;

automatically replacing an imputed haplotype phase for an individual with a randomly modified haplotype phase within the data structure, when the new set of parameters indicate that the randomly modified haplotype phase is more likely than an existing imputed haplotype phase;

extracting at least one final predicted haplotype phase from the data structure as a phased haplotype for an individual; and

storing the at least one final predicted haplotype phase for the individual on a memory of a computer system.

The PTAB determined that the claim describes receiving genotype data followed by mathematical operations of building a data structure describing an HMM and randomly modifying at least one imputed haplotype to automatically recompute the HMM’s parameters. Thus, the PTAB held that the claim is to patent ineligible abstract ideas such as mathematical relationships, formulas, equations and calculations. The PTAB further found that the additional elements in the claim recite generic steps of receiving and storing genotype data in a computer memory, extracting the predicted haplotype phase from the data structure, and storing it in a computer memory, and that these steps are well-known, routine and conventional. Thus, finding the claim ineligible under steps one and two of Alice, the PTAB affirmed the Examiner’s rejection as being to ineligible subject matter.

On appeal, the CAFC followed the two-step test under Alice for determining patent eligibility.

1. Determine whether the claims at issue are directed to a patent-ineligible concept such as laws of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract ideas. If so, proceed to step 2.

2. Examine the elements of each claim both individually and as an ordered combination to determine whether the claim contains an inventive concept sufficient to transform the nature of the claims into a patent-eligible application. If the claim elements involve well-understood, routine and conventional activity they do not constitute an inventive concept.

Under step one, the CAFC found that the claims are directed to abstract ideas including mathematical calculations and statistical modeling. Citing Parker v. Flook, 437 U.S. 584, 595 (1978), the CAFC stated that mathematical algorithms for performing calculations, without more, are patent ineligible under § 101. The CAFC determined that claim 1 involves “building a data structure describing an HMM,” and then “repeatedly randomly modifying at least one of the imputed haplotype phases” to automatically recompute parameters of the HMM until the parameters indicate that the most likely haplotype is found. The CAFC also found that the steps of receiving genotype data, imputing an initial haplotype phase, extracting the final predicted haplotype phase from the data structure, and storing it in a computer memory do not change claim 1 from an abstract idea to a practical application. The CAFC concluded that “Claim 1 recites no application, concrete or otherwise, beyond storing the haplotype phase.”

Stanford argued that the claim provides an improvement of a technological process because the claimed invention provides greater efficiency in computing haplotype phase. However, the CAFC stated that this argument was forfeited because it was not raised before the PTAB.

Stanford also argued that the claimed invention provides an improvement in the accuracy of haplotype predictions rendering claim 1 a practical application rather than an abstract idea. However, the CAFC stated that “the improvement in computational accuracy alleged here does not qualify as an improvement to a technological process; rather, it is merely an enhancement to the abstract mathematical calculation of haplotype phase itself.” The CAFC concluded that “[t]he different use of a mathematical calculation, even one that yields different or better results, does not render patent eligible subject matter.”

Under step two, the CAFC determined that there is no inventive concept that would transform the use of the claimed algorithms and mathematical calculations from an abstract idea to patent eligible subject matter. The steps of receiving, extracting and storing data are well-known, routine and conventional steps taken when executing a mathematical algorithm on a regular computer. The CAFC further stated that claim 1 does not require or result in a specialized computer or a computer with a specialized memory or processor.

Stanford argued that the PTAB failed to consider all the elements of claim 1 as an ordered combination. Specifically, they stated that it is the specific combination of steps in claim 1 “that makes the process novel” and “that provides the increased accuracy over other methods.” The CAFC did not agree stating that the PTAB was correct in its determination that claim 1 merely “appends the abstract calculations to the well-understood, routine, and conventional steps of receiving and storing data in a computer memory and extracting a predicted haplotype.” The CAFC further stated that even if a specific or different combination of mathematical steps yields more accurate haplotype predictions than previously achievable under the prior art, that is not enough to transform the abstract idea in claim 1 into a patent eligible application.

Comments

A key point from this case is that an improvement in computational accuracy does not qualify as an improvement to a technological process. It is merely considered an enhancement to an abstract mathematical calculation. Also, it seems that Stanford made a mistake by not arguing at the PTAB that the claimed invention provides the technological advance of greater efficiency in computing haplotype phase. The CAFC considered this argument forfeited. It is not clear if this argument would have saved Stanford’s patent application, but it certainly would have helped their case.

« Previous Page — Next Page »