CLAIM CONSTRUCTION – WHEN THE MEANING IS CLEAR FROM INTRINSIC EVIDENCE, THERE IS NO REASON TO RESORT TO EXTRINSIC EVIDENCE

Stephen G. Adrian | September 8, 2021

Seabed Geosolutions (US) Inc., v. Magseis FF LLC

Decided August 11, 2021

Before Moore, Linn and Chen

Summary

This precedential opinion reminds us of when it is proper to rely on extrinsic evidence when construing the meaning of claim terms. Claim construction begins with the intrinsic evidence, which includes the claims, written description, and prosecution history. If the meaning of a claim term is clear from the intrinsic evidence, there is no reason to resort to extrinsic evidence.

Background

Fairfield Industries Inc. (the predecessor to Magseis) had sued Seabed Geosolutions for infringement of U.S. Reissue Patent No. RE45,268 directed to seismometers. Seabed Geosolutions petitioned for inter partes review which was instituted by the Board. Interestingly, although not in the opinion, the Board’s institution decision had commented on the meaning of the claim term at issue, “internally fixed.” The institution decision specifically noted that there was nothing in the specification to suggest an intent for “internally fixed” to exclude gimbaled, specifically quoting Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303, 1315 (Fed. Cir. 2005) that the specification “is the single best guide to the meaning of a disputed term” and is usually “dispositive.” The institution decision went on to conclude that the specification does not appear to limit “internally fixed” and instead appears to contemplate a broad meaning.

During the IPR proceeding, however, extrinsic evidence had been presented, causing the Board to find that the specification was not dispositive one way or the other as to the meaning of “internally fixed.” Nine pages of the Board’s decision (also not specifically discussed by the CAFC) was dedicated to a discussion of “internally fixed.” The Board, looking at the extrinsic evidence, thus concluded that in the context of the field of art, one of ordinary skill would understand that the term “fixed” indicates that the geophone is not gimbaled.

Discussion

Every independent claim of the ‘268 patent recites “a geophone internally fixed within” either a housing or an internal compartment. Geophones are used to detect seismic reflections from subsurface structures. The Board concluded that the prior art cited in the IPR failed to disclose the geophone limitation. Seabed appealed by arguing that the Board erred in it claim construction of the geophone limitation.

The CAFC reviews the Board’s claim construction and any supporting determinations based on intrinsic evidence de novo, while subsidiary fact findings involving extrinsic evidence are reviewed for substantial evidence. The CAFC emphasized prior precedent indicating:

For inter partes review petitions filed before November 13, 2018, the Board uses the broadest reasonable interpretation (BRI) standard to construe claim terms. See 37 C.F.R. § 42.100(b) (2017). Under that standard, “claims are given their broadest reasonable interpretation consistent with the specification, not necessarily the correct construction under the framework laid out in Phillips.” PPC Broadband, Inc. v. Corning Optical Commc’ns RF, LLC, 815 F.3d 734, 742 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (citing Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (en banc)). But we still “give[] primacy” to intrinsic evidence, and we resort to extrinsic evidence to construe claims only if it is consistent with the intrinsic evidence. Tempo Lighting, Inc. v. Tivoli, LLC, 742 F.3d 973, 977 (Fed. Cir. 2014); see also Phillips, 415 F.3d at 1318 (“[A] court should discount any expert testimony ‘that is clearly at odds with the claim construction mandated by the claims themselves, the written description, and the prosecution history.’” (quoting Key Pharms. v. Hercon Labs. Corp., 161 F.3d 709, 716 (Fed. Cir. 1998))).

Based on the given standard, the CAFC reviewed the Board’s construction that “geophone internally fixed within [the] housing” requires a non-gimbaled geophone. The CAFC had noted that the Board’s construction was based entirely on extrinsic evidence. This was an error because claim construction begins with examining the intrinsic evidence (claims, written description and prosecution history). Of note, if the meaning of a claim term is clear from the intrinsic evidence, there is no reason to resort to extrinsic evidence (citing Profectus Tech. LLC v. Huawei Techs. Co., 823 F.3d 1375, 1380 (Fed. Cir. 2016)(“Extrinsic evidence may not be used ‘to contradict claimmeaning that is unambiguous in light of the intrinsic evidence.’”(quoting Phillips, 415 F.3d at 1324)).

Based upon the intrinsic evidence, “fixed” carries its ordinary meaning of attached or fastened. The adverb “internally” with “fixed” specifies the geophone’s relationship with the housing, not the type of geophone, which is consistent with the specification. The specification describes mounting the geophone inside the housing as a key feature and says nothing about the geophone being gimbaled or non-gimbaled. The specification touted the “self-contained” approach 18 times and never mentions gimbaled or non-gimbaled, nor providing a reason to exclude gimbals.

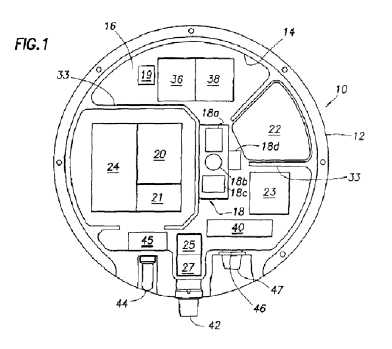

Magseis had attempted to argue that Fig. 1 limits the claims to a non-gimbaled geophone, but this was not persuasive. Fig. 1 merely disclosed geophone 18 as a black box.

The prosecution history also suggests the construction of the word fixed as meaning mounted or fastened. Each time the word came up, the applicant and examiner understood it in its ordinary sense to mean mounted or fastened. Since the intrinsic evidence consistently informed a skilled artisan that fixed means mounted or fastened, “resort to extrinsic evidence is unnecessary.” As such, the Board erred in reaching a narrower interpretation.

Takeaways

If the meaning of a claim term is clear from the intrinsic evidence, there is no reason to resort to extrinsic evidence.

Extrinsic evidence may not be used to contradict claim meaning which is unambiguous in light of the intrinsic evidence.

PTAB’s sua sponte claim construction without adequate notice and opportunity to respond violates patent owner’s procedural rights under APA

Fumika Ogawa | August 26, 2021

Qualcomm Inc. v. Intel Co.

Decided on July 27, 2021

Moore, Reyna, and Stoll. Opinion by Moore.

Summary

The Federal Circuit vacated and remanded inter partes review (IPR) final written decisions from the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, holding that the Board violated the patent owner’s rights to notice and opportunity under Administrative Procedure Act (APA) to respond to the Board’s sua sponte construction of an undisputed claim term.

Details

The appeal stems from six IPR proceedings before the Board where Intel challenged certain claims of U.S. Patent No. 9,608,675 (“the ‘675 Patent”) owned by Qualcomm.

The ‘675 patent relates to power tracking for generating a power supply voltage for a circuit that processes multiple transmit signals sent simultaneously. One of various claim terms at issue in the IPR is “plurality of carrier aggregated transmit signals,” which appears in representative claim 1, among other challenged claims:

1. An apparatus comprising:

a power tracker configured to determine a single power tracking signal based on a plurality of inphase (I) and quadrature (Q) components of a plurality of carrier aggregated transmit signals being sent simultaneously, wherein the power tracker receives the plurality of I and Q components corresponding to the plurality of carrier aggregated transmit signals and generates the single power tracking signal based on a combination of the plurality of I and Q components, wherein the plurality of carrier aggregated transmit signals comprise Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing (OFDM) or Single Carrier Frequency Division Multiple Access (SC-FDMA) signals;

a power supply generator configured to generate a single power supply voltage based on the single power tracking signal; and

a power amplifier configured to receive the single power supply voltage and the plurality of carrier aggregated transmit signals being sent simultaneously to produce a single output radio frequency (RF) signal.

(Emphasis added.)

Intel’s proposed interpretation of the term was:

“signals for transmission on multiple carriers at the same time to increase the bandwidth for a user.”

Qualcomm’s version was:

“signals from a single terminal utilizing multiple component carriers which provide extended transmission bandwidth for a user transmission from the single terminal.”

The increased bandwidth requirement, included in both parties’ interpretations despite a slight difference in wording, is not explicitly recited in the patent claims although the specification indicates that the invention may enable increased bandwidth among other advantages. Unlike other parts of claim interpretations, the requirement was not extensively discussed over the course of an oral hearing held after the briefing. The parties appeared to have agreed upon this issue.

The Board found that all the challenged claims were unpatentable in its final written decisions, construing the term to simply mean “signals for transmission on multiple carriers.” Without the increased bandwidth requirement, the broader scope of the claim term was found obvious over the asserted prior art. Qualcomm appealed, arguing that the Board’s construction of the claim term was made without notice or opportunity to respond.[1]

On appeal, the Federal Circuit found that the Board violated Qualcomm’s rights to notice and a fair opportunity to be heard mandated by due process and the APA. The relevant APA provisions require that the PTO in an IPR proceeding:

- timely inform the patent owner of the matters of fact and law asserted;

- provide all interested parties opportunity for the submission and consideration of facts and arguments and hearing and decision on notice; and

- allow a party to submit rebuttal evidence as may be required for a full and true disclosure of the facts.

(Alterations and citation omitted.)

The Federal Circuit distinguished cases where the Board adopted its own claim construction as to a disputed term. Because the inclusion of the increased bandwidth requirement was not disputed, the present case is governed by SAS Institute, Inc. v. ComplementSoft, LLC, where the Federal Circuit set aside the Board’s final decision deviating from its previously adopted, agreed-upon claim construction for want of a notice and opportunity to respond, because neither party could possibly have imagined that undisputed claim terms were actually “moving targets,” such that the parties had no reason to set forth alternative arguments as to hypothetical constructions not asserted by their opponent.

Intel’s counterarguments were: (1) Qualcomm did not show prejudice; (2) the oral hearing provided Qualcomm notice and an opportunity to respond; and (3) Qualcomm had an option to move for rehearing which would be an adequate opportunity to respond. The Federal Circuit rejected all of them, finding:

(1) Qualcomm was prejudiced.

Qualcomm consistently argued throughout the proceeding that the increased bandwidth requirement was missing in the prior art. Removal of that requirement from the claim construction released Intel from its burden of proof. Also, without notice of the Board’s omission of the requirement in reaching the final decision, Qualcomm was deprived of the opportunity to provide further brief or evidence in support of its claim interpretation.

(2) The oral hearing did not provide Qualcomm notice and opportunity to respond.

During the oral hearing, the increased bandwidth requirement was only mentioned in a single question directed to Intel, whereas Qualcomm was never asked about the requirement. No announcement of the Board’s construction or criticism of the parties’ agreed-upon requirement was presented. Further, the requirement was not included in a sua sponte order made after the hearing, where the Board requested additional briefing on a completely separate claim term.

(3) Qualcomm does not need to seek rehearing before appealing the Board’s decision lacking a requisite notice and opportunity to respond.

The general principle is that a party has the right to appeal a final written decision in an IPR without first requesting a rehearing before the Board. Moreover, an exhaustion requirement should not be imposed where finality of the agency action, such as the final written decision, already exists under the APA. As such, even though rehearing would allow for a more efficient use of judicial resources, it is not a requirement before appealing the final written decision.

Takeaway

- In an IPR, the Board may sua sponte enter its own construction of an undisputed claim term different from those agreed upon by the litigating parties if they are afforded a fair notice and opportunity to respond.

- A litigant in an IPR should be cautious of a potential “moving target” even if there has been an agreement on claim construction with an opposing party.

- Why did Intel not dispute the increased bandwidth requirement in the IPR? Before the IPR institution, the parties had been litigating the same patent in other venues, including an International Trade Commission (“ITC”) investigation. Intel’s version of the claim interpretation in the IPR is actually the same construction which Qualcomm had offered and the ALJ had adopted in the ITC investigation. Intel once asserted the ITC interpretation as “overbroad” under Phillips but nevertheless chose to prove the claim invalidity under broadest reasonable interpretation (applied in the IPR where the petition was filed before the changes to the claim construction standard). The increased bandwidth requirement also appeared in extrinsic evidence cited by Intel. The parallel litigation situation apparently led to the parties’ agreement on the narrower claim interpretation.

[1] Qualcomm also challenged, and the Federal Circuit affirmed, the Board’s construction of a means-plus-function claim term, which is not discussed in this report.

Tags: Administrative Procedure Act > Notice and Opportunity to Respond > PTAB's sua sponte claim construction

Anything Under §101 Can be Patent Ineligible Subject Matter

Miki Motohashi | August 16, 2021

Yanbin Yu, Zhongxuan Zhang v. Apple Inc., Fed. Cir. 2020-1760Yanbin Yu, Zhongxuan Zhang v. Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd., Samsung Electronics America, Inc., Fed. Cir. 2020-1803

Decided on June 11, 2021

Before Newman, Prost, and Taranto (Opinion by Prost, Dissenting opinion by Newman)

Summary

Yu had ’289 patent which is titled “Digital Cameras Using Multiple Sensors with Multiple Lenses” and sued Apple and Samsung at District Court for infringement. The District Court found that the ’289 patent is directed towards an abstract idea and does not include an inventive concept. The District Court held the patent was invalid under §101 and granted the defendant’s motion to dismiss. Yu appealed to the CAFC. The majority panel affirmed the District Court’s decision. However, Judge Newman dissented and wrote that the disputed patent is directed towards a mechanical and electronic device and not an abstract idea. The Judge also pointed out that neither the majority panel nor the District Court decided patentability under §102 or 103.

Details

Background

According to Yu, early digital camera technologies were starting to flourish in the 1990s. However, before the ’289 patent, “the technological limitations of then-existing image sensors—used as the capture mechanism—caused digital cameras to produce lower quality images compared with those produced by traditional film cameras.” The’289 patent was applied in 1999 and issued in 2003. Yu believed that “the ’289 patent solved the technological problems associated with prior digital cameras by providing an improved digital camera having multiple image sensors and multiple lenses.[1]” Yu also explained that “all dual-lens cameras on the market today use the techniques claimed in the ’289 Patent[2]” and therefore, sued Apple and Samsung (“the Defendants”) for infringement of claims 1, 2, and 4 of the ’289 patent in October 2018 (before the ’289 patent expires in 2019). In response, the Defendants filed a Rule 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss, asserting that the claims are directed towards an abstract idea under §101.

Claim 1 of the ’289 patent

1. An improved digital camera comprising:

a first and a second image sensor closely positioned with respect to a common plane, said second image sensor sensitive to a full region of visible color spectrum;

two lenses, each being mounted in front of one of said two image sensors;

said first image sensor producing a first image and said second image sensor producing a second image;

an analog-to-digital converting circuitry coupled to said first and said second image sensor and digitizing said first and said second intensity images to produce correspondingly a first digital image and a second digital image;

an image memory, coupled to said analog-to-digital converting circuitry, for storing said first digital image and said second digital image; and

a digital image processor, coupled to said image memory and receiving said first digital image and said second digital image, producing a resultant digital image from said first digital image enhanced with said second digital image.

The District Court held that the ’289 patent was directed to “the abstract idea of taking two pictures and using those pictures to enhance each other in some way” and “the asserted claims lack an inventive concept, noting “the complete absence of any facts showing that the claimed elements were not well-known, routine, and conventional.” Therefore, the District Court concluded that the ’289 patent was directed to an ineligible subject matter and entered judgment for Defendants. Yu appealed to the CAFC.

Majority Opinion

At the CAFC, as we have seen in the various other §101 precedents, the panel applied the two-step Mayo/Alice framework.

Step 1: “Whether a patent claim is directed to an unpatentable law of nature, natural phenomenon, or abstract idea. Alice, 573 U.S. at 217.”

Step 2: If Step 1 is Yes, “Whether the claim nonetheless includes an “inventive concept” sufficient to “‘transform the nature of the claim’ into a patent-eligible application. Id.”

(If Step 2’s answer is No, the invention is not a patent-eligible subject matter.)

In the majority opinion filed by Judge Prost, as to Step 1, the court applied the approach to the Step 1 inquiry “by asking what the patent asserts to be the focus of the claimed advance over the prior art” and concluded that “claim 1 is “directed to a result or effect that itself is the abstract idea and merely invoke[s] generic processes and machinery” rather than “a specific means or method that improves the relevant technology.” The majority opinion also mentioned that “Yu does not dispute that, as the district court observed, the idea and practice of using multiple pictures to enhance each other has been known by photographers for over a century.” The majority opinion also noted that although, “Yu’s claimed invention is couched as an improved machine (an “improved digital camera”), … “whether a device is “a tangible system (in § 101 terms, a ‘machine’)” is not dispositive”. Thus, the majority panel concluded that “the focus of claim 1 is the abstract idea.”

As to Step 2, the majority opinion concludes that claim 1 does not include an inventive concept sufficient to transform the claimed abstract idea into a patent-eligible invention because “claim 1 is recited at a high level of generality and merely invokes well-understood, routine, conventional components to apply the abstract idea” discussed in Step 1. Yu raised the prosecution history to prove that “the ’289 patent were allowed over multiple prior art references.” Also, Yu argued that the claimed limitations are “unconventional” because “the claimed “hardware configuration is vital to performing the claimed image enhancement.” However, the court was not convinced with this argument and conclude that “the claimedhardware configuration itself is not an advance and does not itself produce the asserted advance of enhancement of one image by another, which, as explained, is an abstract idea.”

Thus, the majority of the court concluded that the ‘’289 patent is not patent-eligible subject matter under §101. Therefore, the court hold for the Defendants.

Dissenting Opinion

In the dissenting opinion, Judge Newman said that “this camera is a mechanical and electronic device of defined structure and mechanism; it is not an “abstract idea” and “a statement of purpose or advantage does not convert a device into an abstract idea.”

The judge explained that “claim 1 is not for the general idea of enhancing camera image”, but “for a digital camera having a designated structure and mechanism that perform specified functions.” The Judge further mentioned, “the ‘abstract idea’ concept with respect to patent-eligibility is founded in the distinction between general principle and specific application.” The Judge quoted Diamond v. Chakrabarty and emphasized that “Congress intended statutory subject matter to ‘include anything under the sun that is made by man.’”

Judge Newman noted that “the ’289 patent may or may not ultimately satisfy all the substantive requirements of patentability”, and noted that neither the majority opinion and the district court discussed §102 and §103.

Takeaway

- After 7 years from Alice, we are still witnessing the profound impact that Alice has on §101 jurisprudence, and waiting for further judicial, legislative, and/or administrative clarity.

- In a previous §101 decision in American Axel (previously reported by John P. Kong), the dissenting opinion by Judges Chen and Wallach criticized that §101 swallowed §112. Now, Judge Newman criticized that §101 swallowed §102 and §103. The dire warning by the Supreme Court about §101 swallowing all of patent law seems to have come full circle.

- Judge Newman’s criticism of §101 swallowing §102 and §103 can be an added argument for appeal for another case and may help get these issues before the Supreme Court.

- John P. Kong said that The approach for determining the Step 1 inquiry, i.e., “by asking what the patent asserts to be the focus of the claimed advance over the prior art” is the source of much of the court’s criticisms. This approach was never vetted, and it conflates §101 with §102 and §103 issues. First, this “focus” is just another name for deriving the “point of novelty,” “gist,” “heart,” or “thrust” of the invention, which had previously been discredited by Supreme Court and Federal Circuit decisions relating to §102 and §103 issues. The problem with tests such as these is that it subtracts out various “conventional” features of the claimed invention (like what is done for the “claimed advance over the prior art”), and thus violates the Supreme Court requirement to consider the claim “as a whole.” If the point of novelty, gist, or heart of the invention contravenes the requirement to consider the claim “as a whole” in the §102 and §103 contexts, then it should likewise contravene the same Supreme Court requirement to consider the claim “as a whole” in the §101 context (as noted in John P. Kong’ “Today’s Problems with §101 and the Latest Federal Circuit Spin in American Axle v. Neapco” powerpoint, Dec. 2020). Judge Newman’s dissent echoes the same.

- John P. Kong also said that Enfish moved up into Step 1 the “improvement in technology” comment in Alice regarding the inventive concept consideration under Step 2 because some computer technology isn’t inherently abstract and thus should not be automatically subject to Alice’s Step 2 and its inventive-concept test. Enfish only had a passing reference to “inquiring into the focus of the claimed advance over the prior art” citing Genetic Techs v. Merial (Fed. Cir. 2016), as support for considering the “improvement in technology” in Alice Step 1. Herein lies the problem. The “improvement in technology” concept pertains to whether the claims are directed to a practical application, instead of an abstract idea. The “claimed advance over prior art” is not a substitute for, and not the same as, determining whether there is a practical application reflected in an improvement in technology. Stated differently, there can still be a practical application (and therefore not an abstract idea) even without checking the prior art and subtracting out “conventional” elements from the claim to discern a “claimed advance over the prior art.” While a positive answer to the “claimed advance over the prior art” would satisfy the “improvement in technology” point as being a practical application justifying eligibility, a negative answer to the “claimed advance over the prior art” does not diminish the claim being directed to a practical application (such as for an electric vehicle charging system, a garage door opener, a manufacturing method for a car’s driveshaft, or for a camera). But, in Electric Power Group v Alstom (Fed. Cir. 2016), the Fed. Cir. considered whether the “advance” is an abstract idea using a computer as a tool or a technological improvement in the computer or computer functionality (in an “improvement in technology” inquiry). And then, in Affinity Labs of Texas LLC v. DirecTV LLC, the Fed Cir cemented the “claimed advance” spin into Step 1, subtracting out “general components such as a cellular telephone, a graphical user interface, and a downloadable application” to arrive at a purely functional remainder that constituted an abstract idea of out-of-region delivery of broadcast content, without offering any technological means of effecting that concept (the 1-2 knockout of: subtract generic elements, and no “how-to” for the remainder). This laid the groundwork for §101 swallowing §§112, 102 and 103.

[1] See Brief, USDC ND of Ca Appeal Nos. 20-1760, -1803.

[2] See Yu v. Apple, United States District Court for the Northern District of California in No. 3:18-cv-06181-JD

A small increase in a Prior Art’s taught range needs to have sufficient reason for the modification to establish obviousness under 35 U.S.C. §103

Michael Caridi | August 6, 2021

Chemours Co. FC, LLC vs Daikin Ind., LTD

Decided on July 22, 2021

NEWMAN, DYK, and REYNA. Opinion by Reyna. Concurring and Dissenting in part by Dyk.

Summary:

Chemours Company FC, LLC, appealed the final written decisions of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board from two inter partes reviews brought by Daikan Industries, Ltd. Chemours argued on appeal that the Board erred in its obviousness factual findings and did not provide adequate support for its analysis of objective indicia of nonobviousness. The CAFC found that the Board’s decision on obviousness was not supported by substantial evidence and that the Board erred in its analysis of objective indicia of nonobviousness. Consequently, they reversed the Board’s decision.

Background:

Chemours Company FC, LLC, appealed the final written decisions of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board from two inter partes reviews brought by Daikan Industries, Ltd., et al. Chemours argues on appeal that the Board erred in its obviousness factual findings and did not provide adequate support for its analysis of objective indicia of nonobviousness.

Two patents were at issue. U.S. Patent No. 7,122,609 (the “’609 patent) and U.S. Patent No. 8,076,4312 (the “’431 patent”). The representative ’609 patent relates to a unique polymer for insulating communication cables formed by pulling wires through melted polymer to coat and insulate the wires, a process known as “extrusion.”

Claim 1 of the ’609 patent is representative of the issues on appeal:

1. A partially-crystalline copolymer comprising tetrafluoroethylene, hexafluoropropylene in an amount corresponding to a hexafluoropropylene index (HFPl) of from about 2.8 to 5.3, said copolymer being polymerized and isolated in the absence of added alkali metal salt, having a melt flow rate of within the range of about 30±3 g/10 min, and having no more than about 50 unstable end groups/106 carbon atoms.

The Board found all challenged claims of the ’609 patent and the ’431 patent to be unpatentable as obvious in view of U.S. Patent No. 6,541,588 (“Kaulbach”).

On appeal, Chemours argued that Daikin did not meet its burden of proof because it failed to show that a person of ordinary skill in the art (“POSA”) would modify Kaulbach’s polymer to achieve the claimed invention.

The Kaulbach reference teaches a polymer for wire and cable coatings that can be processed at higher speeds and at higher temperatures. Kaulbach highlights that the polymer of the invention has a “very narrow molecular weight distribution.” Kaulbach discovered that prior beliefs that polymers in high-speed extrusion application needed broad molecular weight distributions were incorrect because “a narrow molecular weight distribution performs better.” In order to achieve a narrower range, Kaulbach reduced the concentration of heavy metals such as iron, nickel and chromium in the polymer.

In the Kaulbach example relied on by the Board, Sample A11, Kaulbach’s melt flow rate is 24 g/10 min, while the claimed rate of Claim 1 of the ‘609 patent is 30±3 g/10 min.

The Board found that Kaulbach’s melt flow rate range fully encompassed the claimed range, and that a skilled artisan would have been motivated to increase the melt flow rate of Kaulbach’s preferred embodiment to within the claimed range to coat wires faster. Specifically, the Board found:

We also are persuaded that the skilled artisan would have been motivated to increase the [melt flow rate] of Kaulbach’s Sample A11 to be within the recited range in order to achieve higher processing speeds, because the evidence of record teaches that achieving such speeds may be possible by increasing a [polymer’s] [melt flow rate].

In addition, the Board found that the portions of Kaulbach’s disclosure lacked specificity regarding what is deemed “narrow” and “broad,” and that it would have been obvious to “broaden” the molecular weight distribution of the claimed polymer.

Second, Chemours argued that the Board legally erred in its analysis of objective indicia of nonobviousness by showings of commercial success finding an insufficient nexus between the claimed invention and Chemours’s commercial polymer, as the Board required market share evidence to show commercial success.

CAFC Decision:

- Obviousness and teaching away

The CAFC found that the Board ignored the express disclosure in Kaulbach that teaches away from the claimed invention and relied on teachings from other references that were not concerned with the particular problems Kaulbach sought to solve. In other words, the Board did not adequately grapple with why a skilled artisan would find it obvious to increase Kaulbach’s melt flow rate to the claimed range while retaining its critical “very narrow molecular-weight distribution.”

The Court maintained that the Board’s reasoning does not explain why a POSA would be motivated to increase Kaulbach’s melt flow rate to the claimed range, when doing so would necessarily involve altering the inventive concept of a narrow molecular weight distribution polymer. The Court held that this is particularly true in light of the fact that the Kaulbach reference appears to teach away from broadening molecular weight distribution and the known methods for increasing melt flow rate.

Specifically, Kaulbach includes numerous examples of processing techniques that are typically used to increase melt flow rate, which Kaulbach cautions should not be used due to the risk of obtaining a broader molecular weight distribution.

These factors do not demonstrate that a POSA would have had a “reason to attempt” to get within the claimed range, as is required to make such an obviousness finding.

As Chemours persuasively argues, the Board needed competent proof showing a skilled artisan would have been motivated to, and reasonably expected to be able to, increase the melt flow rate of Kaulbach’s polymer to the claimed range when all known methods for doing so would go against Kaulbach’s invention by broadening molecular weight distribution.

The CAFC therefore held that the Board relied on an inadequate evidentiary basis and failed to articulate a satisfactory explanation that is based on substantial evidence for why a POSA would have been motivated to increase Kaulbach’s melt flow rate to the claimed range, when doing so would necessarily involve altering the inventive concept of a narrow molecular weight distribution polymer.

- Commercial success

In addition, Chemours argued that the Board legally erred in its analysis of objective indicia of nonobviousness finding an insufficient nexus between the claimed invention and Chemours’s commercial polymer, and its requirement of market share evidence to show commercial success.

Specifically, Chemours argued that the Board improperly rejected an extensive showing of commercial success by finding no nexus on a limitation-by-limitation basis, rather than the invention as a whole. Chemours contended that the novel combination of these properties drove the commercial success of Chemours’s commercial polymer. Second, Chemours argued the Board improperly required Chemours to proffer market share data to show commercial success.

The CAFC held that contrary to the Board’s decision, the separate disclosure of individual limitations, where the invention is a unique combination of three interdependent properties, does not negate a nexus. The Court recognized that concluding otherwise would mean that nexus could never exist where the claimed invention is a unique combination of known elements from the prior art.

Further, the Court held, quoting prior caselaw, that the Board, erred in its analysis that gross sales figures, absent market share data, “are inadequate to establish commercial success.”

“When a patentee can demonstrate commercial success, usually shown by significant sales in a relevant market, and that the successful product is the invention disclosed and claimed in the patent, it is presumed that the commercial success is due to the patented invention.” J.T. Eaton & Co. v. Atl. Paste & Glue Co., 106 F.3d 1563, 1571 (Fed. Cir. 1997); WBIP, 829 F.3d at 1329. However, market share data, though potentially useful, is not required to show commercial success. See Tec Air, Inc. v. Denso Mfg. Mich. Inc., 192 F.3d 1353, 1360–61 (Fed. Cir. 1999).

The CAFC therefore reversed the Board’s finding of obviousness of the ‘609 and ‘431 claims at issue.

- Dissent

Judge Dyk dissented in part as to the strength of the teaching away by Kaulback. Specifically, he noted that Kaulbach’s copolymer is nearly identical to the polymer disclosed by claim 1 of the ’609 patent. The only material difference between claim 1 and Kaulbach is that Kaulbach discloses (in Sample A11) a melt flow rate of 24 g/10 min, slightly lower than 27 g/10 min, the lower bound of the 30 ± 3 g/10 min rate claimed in claim 1 of the ’609 patent.

As to the teachings of Kaulbach, he went on to note that even though Kaulbach determined that “a narrow molecular weight distribution performs better,” it expressly acknowledged the feasibility of using a broad molecular weight distribution to create polymers for high speed extrusion coating of wires. Hence, Judge Dyk concluded that this is not a teaching away from the use of a higher molecular weight distribution polymer.

Contrary to the majority’s assertion, modifying the molecular weight distribution of Kaulbach’s disclosure of a 24 g/10 min melt flow rate to achieve the 27 g/10 min melt flow rate of claim 1 would hardly “destroy the basic objective” of Kaulbach as the majority claims.

Take away

- There must be clear motivation for a POSA to modify a claimed range even to a small extent. Evidence within the prior art that such a modification would not be beneficial maybe a sufficient teaching away and can negate a finding of increasing the range as an obvious modification. Patent prosecutors should be more assertive in requiring a clear showing of reasons to make a modification of increasing a range outside of a prior art’s taught range.