Authentication method held patent-eligible at Alice Step Two

WHDA Blogging Team | October 14, 2021

CosmoKey Solutions GmbH & Co. v. Duo Security LLC

Decided on October 4, 2021

O’Malley, Reyna, and Stoll. Court opinion by Stoll. Concurring opinion by Reyna.

Summary

The United States District Court for the District of Delaware granted Duo’s motion for judgment on the pleadings under Rule 12(c), arguing that all claims of the patent in dispute are ineligible under 35 U.S.C. 101 as the claims are directed to the abstract idea of authentication and do not recite any patent-eligible inventive concept. On appeal, the Federal Circuit unanimously revered the district court decision, holding that the claims of the patent are patent-eligible under Alice Step Two because they recite a specific improvement to a particular computer-implemented authentication technique. Reyna concurred, arguing that he would resolve the dispute at Alice Step One, not Step Two.

Details

I. Background

(1) Patent in Dispute

CosmoKey Solutions GmbH & Co. (“CosmoKey’s”) owns U.S. Patent No. 9,246,903 (“the ’903 patent”), titled “Authentication Method” and purported to disclose an authentication method that is both low in complexity and high in security.

Claim 1 is the only independent claim of the ’903 patent and reads:

1. A method of authenticating a user to a transaction at a terminal, comprising the steps of:

transmitting a user identification from the terminal to a transaction partner via a first communication channel,

providing an authentication step in which an authentication device uses a second communication channel for checking an authentication function that is implemented in a mobile device of the user, as a criterion for deciding whether the authentication to the transaction shall be granted or denied, having the authentication device check whether a predetermined time relation exists between the transmission of the user identification and a response from the second communication channel,

ensuring that the authentication function is normally inactive and is activated by the user only preliminarily for the transaction,

ensuring that said response from the second communication channel includes information that the authentication function is active, and

thereafter ensuring that the authentication function is automatically deactivated.

(2) The District Court

CosmoKey brought a civil lawsuit against Duo Security, Inc. (“Duo”) for infringement of the ’903 patent at the United States District Court for the District of Delaware (“the district court”). Duo moved for judgment on the pleadings pursuant to Rule 12(c) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, arguing that the claims of the ’903 patent are ineligible under 35 U.S.C. 101.

The district court agreed with Duo, holding that the patent claims were invalid. The district court reasoned that the claims “are directed to the abstract idea of authentication—that is, the verification of identity to permit access to transactions” at Alice Step One, and that “the [’]903 patent merely teaches generic computer functionality to perform the abstract concept of authentication; and it therefore fails Alice’s step two inquiry.” In so holding, the district court determined that the patent itself admits that “the detection of an authentication function’s activity and the activation by users of an authentication function within a predetermined time relation were well-understood and routine, conventional activities previously known in the authentication technology field.”

CosmoKey appealed the district court’s judgment.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit (“the Court”) unanimously revered the district court decision, holding that the claims of the patent are patent-eligible under Alice step two.

Before discussing Alice Steps One and Two, the Court referred to several cases in which the Court has previously considered the eligibility of various claims generally directed to authentication and verification under § 101. However, the Court compared the claims of the ’903 patent with none of those claims held patent-eligible or patent-ineligible. See Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., 822 F.3d 1327, 1334 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (“The Supreme Court has not established a definitive rule to determine what constitutes an “abstract idea” sufficient to satisfy the first step of the Mayo/Alice inquiry. … Rather, both this court and the Supreme Court have found it sufficient to compare claims at issue to those claims already found to be directed to an abstract idea in previous cases.”).

(1) Alice Step One

The Court stated that the critical question at Alice Step One for this case is whether the correct characterization of what the claims are directed to is either an abstract idea or a specific improvement in computer verification and authentication techniques.

Interestingly however, the Court stated that it needs not answer this question because even if the Court accepts the district court’s narrow characterization of the ’903 patent claims, the claims satisfy Alice step two.

The Court noted in footnote 3 that this very approach was followed in Amdocs (Israel) Ltd. v. Openet Telecom, Inc., 841 F.3d 1288, 1303 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (explaining that “even if [the claim] were directed to an abstract idea under step one, the claim is eligible under step two”).

(2) Alice Step Two

The district court recognized that the specification indicates that the “difference between [the] prior art methods and the claimed invention is that the [’]903 patent’s method ‘can be carried out with mobile devices of low complexity’ so that ‘all that has to be required from the authentication device function is to detect whether or not this function is active’” and that “the only activity that is required from the user for authentication purposes is to activate the authentication function at a suitable timing for the transaction.” But the district court cited column 1, lines 15–53 of the specification as purportedly admitting that detection of activation of an authentication function’s activity and the activation by users of an authentication function within a pre-determined time relation were “well-understood and routine, conventional activities previously known in the authentication technology field” (emphasis added).

The Court criticized the district court’s reliance on column 1, lines 15–53 as misplaced. The Court stated that, while column 1, lines 30–46 describes three prior art references, none teach the recited claim steps, and read in context, the rest of the passage cited by the district court makes clear that the claimed steps were developed by the inventors, are not admitted prior art, and yield certain advantages over the described prior art (emphasis added).

Duo also argued that using a second communication channel in a timing mechanism and an authentication function that is normally inactive, activated only preliminarily, and automatically deactivated is itself an abstract idea and thus cannot contribute to an inventive concept, and far from concrete (emphasis added). The Court disagreed, stating that the claim limitations are more specific and recite an improved method for overcoming hacking by ensuring that the authentication function is normally inactive, activating only for a transaction, communicating the activation within a certain time window, and thereafter ensuring that the authentication function is automatically deactivated (emphasis added). Referring to the Court’s recognition in Ancora Techs., Inc. v. HTC Am., Inc., 908 F.3d 1343 (Fed. Cir. 2018) that improving computer or network security can constitute “a non-abstract computer-functionality improvement if done by a specific technique that departs from earlier approaches to solve a specific computer problem,” the Court emphasized that, as the specification itself makes clear, the claims recite an inventive concept by requiring a specific set of ordered steps that go beyond the abstract idea identified by the district court and improve upon the prior art by providing a simple method that yields higher security (emphasis added).

II. Concurring Opinion

Judge Reyna’s concurrence challenged the Court’s approach of accepting the district court’s analysis under Alice step one and resolving the case under Alice step two. Judge Reyna argues that Alice Step two comes into play only when a claim has been found to be directed to patent-ineligible subject matter. He concluded that, employing step one, the claims at issue are directed to patent-eligible subject matter because, as the Court opinion stated, “[t]he ’903 Patent claims and specification recite a specific improvement to authentication that increases security, prevents unauthorized access by a third party, is easily implemented, and can advantageously be carried out with mobile devices of low complexity,” which is a step-one rationale.

Takeaway

· In the Alice inquiry, courts may assume that the claim in question does not pass Alice Step One without detailed analysis, and immediately move on to Alice Step Two.

· At both Alice Steps One and Two, the Court almost always inquires about improvements, i.e., the claimed advance over the prior art (“Under Alice step one, we consider “what the patent asserts to be the ‘focus of the claimed advance over the prior art.’”; “Turning then to Alice step two, we “consider the elements of each claim both individually and ‘as an ordered combination’ to determine whether the additional elements ‘transform the nature of the claim’ into a patent-eligible ap- plication.” … In computer-implemented inventions, the computer must perform more than “well-understood, routine, conventional activities previously known to the industry.””) (emphasis added). This approach may appear different from the views of the Supreme Court and the USPTO. See Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 132 S.Ct. 1289, 1304 (2012) (“We recognize that, in evaluating the significance of additional steps, the § 101 patent-eligibility inquiry and, say, the § 102 novelty inquiry might sometimes overlap. But that need not always be so.””); MPEP 2106.04(d)(1) (“[T]he improvement analysis at Step 2A [(Alice Step One)] Prong Two differs in some respects from the improvements analysis at Step 2B [(Alice Step Two)]. Specifically, the “improvements” analysis in Step 2A determines whether the claim pertains to an improvement to the functioning of a computer or to another technology without reference to what is well-understood, routine, conventional activity.”) (emphasis added).

Prosecution Refreshers – Incorporating Foreign Priority Application by Reference, Translations, Means-Plus-Function

John Kong | October 7, 2021

Team Worldwide Corp. v. Intex Recreation Corp.

Decided September 9, 2021

Opinion by: Chen, Newman, and Taranto

Summary:

The claimed “pressure controlling assembly” was found to be a means-plus-function claim element. Because the specification did not disclose any corresponding structure to perform at least one of the associated functions for this pressure controlling assembly, the claim was held to be indefinite. The specification did not disclose any corresponding structure because the portions of the foreign priority application (that disclosed corresponding structure) were omitted in the US application, and there was no incorporation by reference of the foreign priority application.

Procedural History:

This is a non-precedential Federal Circuit decision for an appeal from a PTAB post-grant review (PGR) decision. Intex petitioned for a PGR on Team Worldwide’s USP 9,989,979 patent (filed Aug. 29, 2014). The ‘979 patent is a divisional application of an earlier pre-AIA application. The ‘979 patent, filed after the March 16, 2013 effective date for AIA, is subject to AIA’s PGR unless each claim is supported in its pre-AIA parent application under 35 USC §112(a) for written description support and enablement. However, the earlier pre-AIA application at least did not have written description support for the claimed “pressure controlling assembly.” Thus, the ‘979 patent was subject to AIA’s post-grant review. The PTAB held that “pressure controlling assembly” is a means-plus-function (MPF) claim element subject to interpretation under 35 USC §112(f) and the ‘979 claims are invalid as indefinite under 35 USC §112(b) because there is no corresponding structure disclosed in the specification for at least one of the claimed functions thereof. The Federal Circuit affirmed.

Background:

The ‘979 patent relates to an inflator for an air mattress. Representative claim 1:

1. An inflating module adapted to an inflatable object comprising an inflatable body, the inflating module used in conjunction with a pump that provides primary air pressure and comprising:

a pressure controlling assembly configured to monitor air pressure in the inflatable object after the inflatable body has been inflated by the pump; and

a supplemental air pressure providing device,

wherein the pressure controlling assembly is configured to automatically activate the supplemental air pressure providing device when the pressure controlling assembly detects that the air pressure inside the inflatable object decreases below a predetermined threshold after inflation by the pump, and to control the supplemental air pressure providing device to provide supplemental air pressure to the inflatable object so as to maintain the air pressure of the inflatable object within a predetermined range.

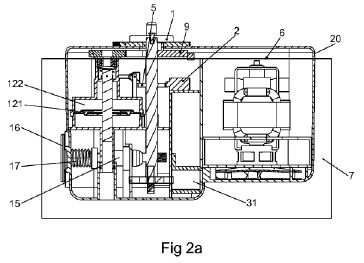

The ‘979 patent describes the pressure controlling assembly almost exclusively in functional terms, including the functions recited in claim 1. There is one sentence that states “[a]fter the supplemental air pressure providing device is in a standby mode, a pressure controlling assembly 121/122 as described starts monitoring air pressure in the inflatable object” (col. 4, lines 48-51). No explanation is provided about elements 121/122 shown in Fig. 2a:

Both the ‘979 and its parent application (having the same specification) claim foreign priority from CN 201010186302. However, neither US application incorporates the CN ‘302 application by reference.

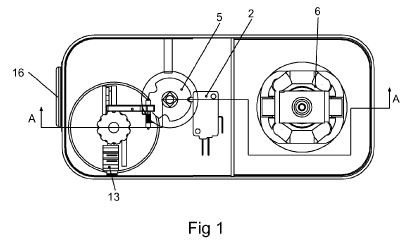

According to a translation of CN ‘302 application, CN ‘302 does describe an “air pressure control mechanism” that includes “air valve plate 121” and “chamber 122” which move in response to changing air pressure within the attached inflatable device. CN ‘302 further describes a switch 13, see Fig. 1 (same drawings in both CN ‘302 and the ‘979 patent and its parent):

According to CN ’302, as translated, “[w]hen the air pressure value inside the inflatable product is greater than the reset mechanism’s preset value, the air pressure control mechanism shifts upward, the second switch 13 is closed by the projection pressing against it, and the automatic reinflation mechanism halts reinflation” and “[w]hen the air pressure value inside the inflatable product is less than the reset mechanism’s preset value, the air pressure control mechanism shifts downward, the projection is removed from second switch 13 causing it to disconnect, and the automatic reinflation mechanism starts reinflation.”

Neither the ‘979 patent, nor its parent application, includes the above-noted structures of an air valve plate for reference number 121 nor the chamber for reference number 122. Neither US applications mention any switch 13 nor the above-noted operations involving the switch 13 for starting or stopping reinflation. Reference number 13 is not at all described in the ‘979 specification, nor in its parent’s specification.

The court also noted that the original specification in both the ‘979 patent and its parent application did not even mention reference numbers 121 and 122. It was added to the specification during prosecution to overcome an Examiner’s drawing objection for including those reference numbers in a drawing that were not described in the specification.

MPF Primers:

- If a claim does not recite the word “means,” it creates a rebuttable presumption that §112(f) does not apply.

- A presumption against applying §112(f) is overcome “if the challenger demonstrates that the claim term fails to recite sufficiently definite structure or else recites function without reciting sufficient structure for performing that function.” Williamson v. Citrix Online, LLC, 792 F.3d 1339, 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (en banc).

Decision:

Claim construction is reviewed de novo, considering the intrinsic record, i.e., the claims, specification, and prosecution history, and any extrinsic evidence.

For the claim itself, like the word “means,” the word “assembly” is a generic nonce word. “Like the claim term ‘mechanical control assembly’ in MTD Products, ‘the claim language reciting what the [pressure] control[ing] assembly is ‘configured to” do is functional,’ and thus the claim format supports applicability of §112(f).”

As for the specification, the court agrees with the PTAB that the specification’s “mere reference to items 121 and 122, without further description, does not convey that the term ‘pressure controlling assembly’ itself connotes sufficient structure.” The court also noted that the specification does not indicate that the patentee acted as his own lexicographer to define the “pressure controlling assembly” to be a structural term.

As for the prosecution history, the fact that the examiner cited prior art pressure sensors as disclosing the claimed “pressure controlling assembly” does not establish that the term itself connotes structure. While a pressure sensor may perform some of the functions of the “pressure controlling assembly,” the examiner’s reliance on a pressure sensor says nothing about the term itself connoting structure. The court also rejected giving weight to the fact that the examiner did not apply §112(f) for interpreting the subject term.

As for extrinsic evidence, Team’s expert testimony was deemed conclusory and unsupported by evidence. Team’s expert relied on a dictionary definition of “pressure control” – any device or system able to maintain, raise, or lower pressure in a vessel or processing system. However, such a definition sheds no light on “pressure controlling assembly” being used in common parlance to connote structure. Even the purported admissions by Intex’s expert (i.e., that the term controls pressure and is an assembly, that devices exist that sense or control pressure, and that a cited prior art reference depicted “an apparatus that controls the pressure”) merely indicates that devices existed that can perform some of the functions of the “pressure controlling assembly.” However, none of the experts’ testimony establish that “pressure controlling assembly” is “used in common parlance or by [skilled artisans] to designate a particular structure or class of structures.”

As for prior art references that refer to a “pressure controlling assembly,” the court agreed with the PTAB’s assessment that such extrinsic evidence “demonstrates, at best, that the term is used as a descriptive term across a broad spectrum of industries, having a broad range of structures. The record does not include sufficient evidence to demonstrate that the term ‘pressure controlling assembly’ is used in common parlance or used to designate a particular structure by [the skilled artisan].”

As for the functions claimed for the “pressure controlling assembly,” there was no dispute:

- monitoring air pressure in the inflatable object after the inflatable body has been inflated by the pump;

- detecting that the air pressure inside the inflatable object decreases below a predetermined threshold after inflation by the pump;

- automatically activating the supplemental air pressure providing device when the pressure controlling assembly detects that the air pressure inside the inflatable object decreases below the predetermined threshold after inflation by the pump; and

- controlling the supplemental air pressure providing device to provide supplemental air pressure to the inflatable object so as to maintain the air pressure of the inflatable object within a predetermined range.

The court agrees with the PTAB that the patent fails to disclose any corresponding structure for at least #3. Team’s expert’s conclusory testimony that a skilled artisan would recognize that 121 and 122 in Fig. 2a interacts with element 13 in Fig. 1 to activate the supplemental air pressure providing device is not supported by any evidence. Nothing in the patent describes 13 to be a switch, much less how it interacts with 121 and 122, whatever those are.

As for the fact that CN ‘302 is part of the prosecution history, the court noted that the content of any document or reference submitted during prosecution by itself is not sufficient to remedy this missing disclosure of corresponding structure. In reference to B. Braun Medical, Inc. v. Abbott Lab., 124 F.3d 1419, 1424 (Fed. Cir. 1997), Braun’s reference to the “prosecution history” is in reference to affirmative statements made by the applicant during prosecution (such as in an Amendment or in a sworn declaration regarding the relationship between something in a drawing and a claimed MPF claim element) linking or associating corresponding structure with a claimed function. “[W]e decline to hold that a Chinese-language priority document, whose potentially relevant disclosure was omitted from the United States patent application family, provides a clear link or association between the claimed ‘pressure controlling assembly’ and any structure recited or disclosed in the ‘979 patent.”

Takeaways:

- This case is a good refresher for MPF interpretation.

- 37 CFR 1.57 addresses the situation where there is an inadvertent omission of a portion of the specification or drawings, by allowing a claim for foreign priority to be considered an incorporation by reference as to any inadvertently omitted portion of the specification or drawings from that foreign priority application. 37 CFR 1.57(a) (pre-AIA) would apply to the parent application of the ‘979 patent. 37 CFR 1.57(b) (AIA) would apply to the application leading to the ‘979 patent. However, any amendment made pursuant to 37 CFR 1.57 must be made before the close of prosecution. It is unclear why the applicant did not use the provisions of 37 CFR 1.57 in this case. Once the application is issued into a patent, as was the case here, the incorporation by reference provisions of 37 CFR 1.57 no longer apply. As noted in MPEP 217(II)(E), “In order for the omitted material to be included in the application, and hence considered to be part of the disclosure, the application must be amended to include the omitted portion. Therefore, applicants can still intentionally omit material contained in the prior-filed application from the application containing the priority or benefit claim without the material coming back in by virtue of the incorporation by reference of 37 CFR 1.57(b). Applicants can maintain their intent by simply not amending the application to include the intentionally omitted material.” Presumably, because the applicant for the ‘979 patent and its parent never took advantage of 37 CFR 1.57 during prosecution, the missing subject matter was treated as “intentionally omitted material” and does not come back into the patent by virtue of 37 CFR 1.57.

- The specification of the ‘979 patent and of its parent did not include any incorporation by reference of its foreign priority application. The applicant also did not take advantage of 37 CFR 1.57 during prosecution (see above). Accordingly, the foreign priority application was deemed “omitted from the United States patent application family.” And, just having it in the file wrapper at the USPTO is still not enough. The applicant, during prosecution, must correct any missing link between any MPF claim elements and its corresponding structure in the specification. Here, IF the Chinese priority application had been incorporated by reference or IF 37 CFR 1.57(a) (pre-AIA) and 37 CFR 1.57(b) (AIA) were used, an amendment to the specification to ADD inadvertently omitted English language translations of the corresponding structure from the priority application could have been submitted. Such amendments to the specification would not be deemed “new matter” because of the incorporation by reference of the foreign priority application.

- Always check the English language translation. It seems odd that no one noticed the omission of any description of the elements 121, 122, and 13 from the Chinese priority application. During the prosecution of the parent and the ‘979 patent, the Examiner identified at least a dozen different reference numbers that were not described in the specification. When preparing an application, or translating one, the specification should be checked for a description for each and every reference number used in the drawings.

Tags: Foreign Priority > Incorporation by reference > means-plus-function > translation

CLAIMS SHOULD PROVIDE SUFFICIENT SPECIFICITY TO IMPROVE THE UNDERLYING TECHNOLOGY

Bo Xiao | September 30, 2021

Universal Secure Registry LLC, v. Apple Inc., Visa Inc., Visa U.S.A. Inc.

Before TARANTO, WALLACH, and STOLL, Circuit Judges. STOLL

Summary

The Federal Circuit upheld a decision that all claims of the asserted patents are directed to an abstract idea and that the claims contain no additional elements that transform them into a patent-eligible application of the abstract idea.

Background

USR sued Apple for allegedly infringing U.S. Patent Nos. 8,856,539; 8,577,813; 9,100,826; and 9,530,137 that are directed to secure payment technology for electronic payment transactions. The four patents involve different authentication technology to allow customers to make credit card transactions “without a magnetic-stripe reader and with a high degree of security.”

The magistrate judge determined that all the representative claims were not directed to an abstract idea. Particularly it was concluded that the claimed invention provided a more secure authentication system. The magistrate judge also explained that the non-abstract idea determination is based on that “the plain focus of the claims is on an improvement to computer functionality itself, not on economic or other tasks for which a computer is used in its ordinary capacity.” However, the district court judge disagreed and concluded that the asserted claims failed at both Alice steps and the claimed invention was directed to the abstract idea of “the secure verification of a person’s identity.” The district court explained that the patents did not disclose an inventive concept—including an improvement in computer functionality—that transformed the abstract idea into a patent-eligible application.

The Federal Circuit concluded that the asserted patents claim unpatentable subject matter and thus upheld the district court’s decision.

Discussion

The Federal Circuit addressed all asserted patents. The claims in the four patents have fared similarly. The discussion here is focused on the ‘137 patent. The ’137 patent is a continuation of the ’826 patent and discloses a system for authenticating the identities of users. Claim 12 is representative of the ’137 patent claims at issue, reciting

12. A system for authenticating a user for enabling a transaction, the system comprising:

a first device including:

a biometric sensor configured to capture a first biometric information of the user;

a first processor programmed to: 1) authenticate a user of the first device based on secret information, 2) retrieve or receive first biometric information of the user of the first device, 3) authenticate the user of the first device based on the first biometric, and 4) generate one or more signals including first authentication information, an indicator of biometric authentication of the user of the first device, and a time varying value; and

a first wireless transceiver coupled to the first processor and programmed to wirelessly transmit the one or more signals to a second device for processing;

wherein generating the one or more signals occurs responsive to valid authentication of the first biometric information; and

wherein the first processor is further programmed to receive an enablement signal indicating an approved transaction from the second device, wherein the enablement signal is provided from the second device based on acceptance of the indicator of biometric authentication and use of the first authentication information and use of second authentication information to enable the transaction.

Claim 12 recites a system for authenticating the identities of users, including a first device. The first device can include a biometric sensor, a first processor, and a first wireless transceiver, where the device utilizes authentication of a user’s identity to enable a transaction.

The district court emphasized that the claims recite, and the specification discloses, generic well-known components—“a device, a biometric sensor, a processor, and a transceiver—performing routine functions—retrieving, receiving, sending, authenticating—in a customary order.”

The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court and found that the claims of ‘137 patent include some limitations but still are not sufficiently specific. The Federal Circuit cited their previous decision, Solutran, Inc. v. Elavon, Inc (Fed. Cir. 2019) that held claims abstract “where the claims simply recite conventional actions in a generic way” without purporting to improve the underlying technology. The Court explained that claim 12 does not tell a person of ordinary skill what comprises the secret information, first authentication information, and second authentication information.

USR cited Finjan, Inc. v. Blue Coat Systems, Inc (Fed. Cir. 2018), arguing that the claim is akin to the claim in Finjan whose claims are directed to a method of providing computer security by scanning a downloadable file and attaching the scanned results to the downloadable file in the form of a “security profile.” However, the Court differentiated Finjan, explaining that Finjan employed a new kind of file enabling a computer system to do things it could not do before, namely “behavior-based” virus scans. In contrast, the claimed invention combines conventional authentication techniques to achieve an expected cumulative higher degree of authentication integrity. The claimed idea of using three or more conventional authentication techniques to achieve a higher degree of security is abstract without some unexpected result or improvement. The Court also acknowledged that some of the dependent claims provide more specificity on these aspects, but still concluded the claimed is still merely conventional and the specification discloses that each authentication technique is conventional.

The district court also turned to Alice step two to determine that claim 12 “lacks the inventive concept necessary to convert the claimed system into patentable subject matter.” USR asserted that the use of a time-varying value, a biometric authentication indicator, and authentication information that can be sent from the first device to the second device form an inventive concept. The Federal Circuit rejected this argument, explaining that the specification makes clear that each of these devices and functions is conventional because the patent acknowledged that the step of generating time-varying codes for authentication of a user is conventional and long-standing. USR further argued that authenticating a user at two locations constitutes an inventive concept because it is locating the authentication functionality at a specific, unconventional location within the network. However, the Court found that the specification of the patent suggests that the claims only recite a conventional location for the authentication functionality and thus rejected the argument. The court further stated that there is nothing in the specification suggesting, or any other factual basis for a plausible inference (as needed to avoid dismissal), that the combination of these conventional authentication techniques results in an unexpected improvement beyond the expected sum of the security benefits of each individual authentication technique.

The Federal Circuit ruled that all the patents simply described well-known and conventional ways to perform authentication and did not include any technological improvements that transformed those abstract ideas into patent-eligible inventions. The Court also cited several of its previous decisions related to patent invalidity under Alice, noting that “patent eligibility often turns on whether the claims provide sufficient specificity to constitute an improvement to computer functionality itself.”

Takeaway

- An abstract idea is not patentable if it does not provide an inventive solution to a problem in implementing the idea.

- Claims may be abstract even when they are directed to physical devices but include generic well-known components that perform conventional actions in a generic way without improving the underlying technology or only to achieve an expected cumulative improvement.

PATENT CLAIMS CANNOT BE CONSTRUED ONE WAY FOR ELIGIBILITY AND ANOTHER WAY FOR INFRINGEMENT

Andrew Melick | September 17, 2021

Data Engine Technologies LLC v. Google LLC

Decided on August 26, 2021

Reyna, Hughes, Stoll. Opinion by Stoll.

Summary:

This case is a second appeal to the CAFC. In the first appeal, the CAFC reversed the district court and determined that certain claims of patents owned by Data Engine Technologies LLC (DET) directed to spreadsheet technologies are patent eligible subject matter. In arguing patent eligible subject matter, DET emphasized the claimed improvement as being unique to three-dimensional spreadsheets. On remand, the district court construed the preamble of the claims having the phrase “three-dimensional spreadsheet” as limiting, and based on this claim construction, granted Google’s motion for summary judgment of noninfringement. In this appeal, the CAFC affirmed the district court’s determination that the preamble of the claims is limiting and that the district court’s construction of the term “three-dimensional spreadsheet” is correct. Thus, the CAFC affirmed the district court’s summary judgment of noninfringement.

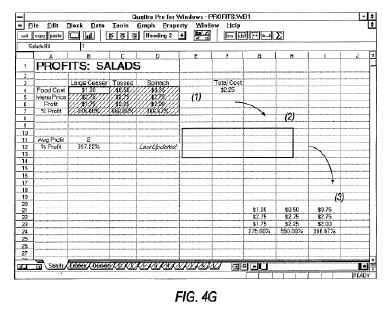

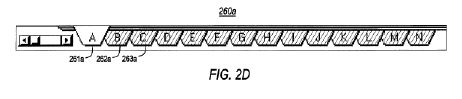

Details:

DET’s patents at issue in this case are U.S. Patent Nos. 5,590,259; 5,784,545; and 6,282,551 directed to systems and methods for displaying and navigating three-dimensional electronic spreadsheets. They describe providing “an electronic spreadsheet system including a notebook interface having a plurality of notebook pages, each of which contains a spread of information cells, or other desired page type.” Figs. 2A and 2D of the ‘259 patent are shown below. Fig. 2A shows a spreadsheet page having notebook tabs along the bottom edge. Fig. 2D shows just the notebook tabs of the spreadsheet.

Claim 12 of the ‘259 patent is a representative claim and is provided below:

12. In an electronic spreadsheet system for storing and manipulating information, a computer-implemented method of representing a three-dimensional spreadsheet on a screen display, the method comprising:

displaying on said screen display a first spreadsheet page from a plurality of spreadsheet pages, each of said spreadsheet pages comprising an array of information cells arranged in row and column format, at least some of said information cells storing user-supplied information and formulas operative on said user-supplied information, each of said information cells being uniquely identified by a spreadsheet page identifier, a column identifier, and a row identifier;

while displaying said first spreadsheet page, displaying a row of spreadsheet page identifiers along one side of said first spreadsheet page, each said spreadsheet page identifier being displayed as an image of a notebook tab on said screen display and indicating a single respective spreadsheet page, wherein at least one spreadsheet page identifier of said displayed row of spreadsheet page identifiers comprises at least one user-settable identifying character;

receiving user input for requesting display of a second spreadsheet page in response to selection with an input device of a spreadsheet page identifier for said second spreadsheet page;

in response to said receiving user input step, displaying said second spreadsheet page on said screen display in a manner so as to obscure said first spreadsheet page from display while continuing to display at least a portion of said row of spreadsheet page identifiers; and

receiving user input for entering a formula in a cell on said second spreadsheet page, said formula including a cell reference to a particular cell on another of said spreadsheet pages having a particular spreadsheet page identifier comprising at least one user-supplied identifying character, said cell reference comprising said at least one user-supplied identifying character for said particular spreadsheet page identifier together with said column identifier and said row identifier for said particular cell.

In the first appeal regarding patent eligibility, DET argued that a key aspect of the patents “was to improve the user interface by reimagining the three-dimensional electronic spreadsheet using a notebook metaphor.” DET argued that claim 12 is directed to patent-eligible subject matter because it is to a concept that solves “a problem that is unique to not only computer spreadsheet applications …., but specifically three-dimensional electronic spreadsheets.” In that appeal, the CAFC agreed that claim 12 is to patent eligible subject matter and remanded to the district court.

On remand, during claim construction, a dispute arose over whether the preamble is a limitation of the claims requiring construction, and if so, what is the proper construction of the term. The district court determined that the preamble is limiting and determined that the term “three-dimensional spreadsheet” means a “spreadsheet that defines a mathematical relation among cells on different spreadsheet pages, such that cells are arranged in a 3-D grid.” Based on this interpretation, Google moved for summary judgment of noninfringement because Google Sheets is not a “three-dimensional spreadsheet” as required by the claims. The district court granted the motion because “Google Sheets does not allow a user to define the relative position of cells in all three dimensions and is, therefore, incapable of infringing” the claims.

In this appeal, DET argued that the preamble term “three-dimensional spreadsheet” is not limiting and thus does not have patentable weight. The CAFC disagreed stating that a patentee cannot rely on language found in the preamble of the claim to successfully argue patent eligible subject matter, and then later assert that the preamble term has no patentable weight for purposes of showing infringement. The CAFC stated that “[w]e have repeatedly rejected efforts to twist claims, ‘like a nose of wax,’ in ‘one way to avoid [invalidity] and another to find infringement.’” In citing an analogous case, the CAFC stated that it cannot be argued that the preamble has no weight when the preamble was used in prosecution to distinguish prior art. In re Cruciferous Sprout Litig., 301 F.3d 1343, 1347–48 (Fed. Cir. 2002). The CAFC concluded that because DET emphasized the preamble term to support patent eligibility, the preamble term “three-dimensional spreadsheet” is limiting.

DET next argued that the construction of “three-dimensional spreadsheet” does not require “a mathematical relation among cells on different spreadsheet pages” as required by the district court’s construction. The CAFC stated that the claim language and the specification do not provide guidance on whether the mathematical relation is required. However, the CAFC looked to the prosecution history. To overcome a rejection based on a prior art reference, the applicant provided a definition of a “true” three-dimensional spreadsheet and stated that the prior art does not provide a true 3D spreadsheet. According to the applicant, a “true” three-dimensional spreadsheet “defines a mathematical relation among cells on the different pages so that operations such as grouping pages and establishing 3D ranges have meaning.” Based on this definition provided in the prosecution history, the CAFC stated that the district court properly interpreted “three-dimensional spreadsheet” as requiring a mathematical relation among cells on different spreadsheet pages.

DET argued that the definition provided in the prosecution history does not rise to the level of “clear and unmistakable” disclaimer when read in context. Specifically, DET stated in the same remarks that the prior art reference is a three-dimensional spreadsheet, and thus, could not have been distinguishing the prior art based on the three-dimensional spreadsheet feature. DET stated that they distinguished the prior art on the basis that the prior art linked different user-named spreadsheet files and that this is not the same as the claimed “user-named pages in a 3D spreadsheet.” Thus, DET argued that the statements defining a “true” 3D spreadsheet are irrelevant. However, the CAFC stated that they have held patentees to distinguishing statements made during prosecution even if they said more than needed to overcome a prior art rejection citing Saffran v. Johnson & Johnson, 712 F.3d 549, 559 (Fed. Cir. 2013). Thus, the CAFC concluded that even if the specific definition of a “true” 3D spreadsheet was not necessary to overcome the rejection, the express definition was provided, and DET cannot escape the effect of this statement made to the USPTO by suggesting that the statement was not needed to overcome the rejection. The CAFC affirmed the district court’s claim construction and its summary judgment of noninfringement.

Comments

In litigation, you will not be able to vary the construction of claims one way for validity and another way for infringement. Also, if you rely on features in the preamble of a claim for validity, the preamble will be considered as limiting and having patentable weight for infringement purposes.

Another key point from this case is that during prosecution of a patent application, you should say as little as possible to distinguish the prior art. Distinguishing statements in the prosecution history, even if not necessary to overcome the prior art, can be used to limit your claims.

« Previous Page — Next Page »