Claim differentiation helps broaden the scope of a claim to a Fuse end cap

Andrew Melick | April 29, 2022

Littlefuse, Inc. v. Mersen USA EP Corp.

Decided: April 4, 2022

Prost, Bryson and Stoll. Opinion by Bryson.

Summary:

Littlefuse sued Mersen for infringement of its patent to a fuse end cap. In construing the claims, the district court held that the claims are limited to a multi-piece apparatus even though some dependent claims recite a single-piece apparatus. Upon review of the claims, specification, and prosecution history, and based on principles of claim differentiation, the CAFC concluded that the district court’s construction is incorrect. The CAFC concluded that the independent claims should be construed as including multi-piece fuse end caps as well as single-piece fuse end caps. Thus, the CAFC vacated the district court’s judgment and remanded.

Details:

Littlefuse owns U.S. Patent No. 9,564,281 to a “fuse end cap for providing an electrical connection between a fuse and an electrical conductor.” Independent claim 1 is provided:

1. A fuse end cap comprising:

a mounting cuff defining a first cavity that receives an end of a fuse body, the end of the fuse body being electrically insulating;

a terminal defining a second cavity that receives a conductor, wherein the terminal is crimped about the conductor to retain the conductor within the second cavity; and

a fastening stem that extends from the mounting cuff and into the second cavity of the terminal that receives the conductor.

Dependent claims 8 and 9 are also important in this case and are provided:

8. The fuse end cap of claim 1, wherein the mounting cuff and the terminal are machined from a single, contiguous piece of conductive material.

9. The fuse end cap of claim 1, wherein the mounting cuff and the terminal are stamped from a single, contiguous piece of conductive material.

The specification describes three embodiments: (1) a “machined end cap” that may be manufactured from a single piece of any suitable, electrically conductive material; (2) a “stamped end cap” that may be manufactured from a single piece of any suitable, electrically conductive material; and (3) an “assembled end cap” in which the terminal and mounting cuff are formed from separate pieces of material, the material being any suitable, electrically conductive material. With the “assembled end cap,” the terminal and mounting cuff are “joined together, such as by press-fitting a fastening stem of the mounting cuff into the cavity of the terminal” or by using “a variety of other fastening means including … various adhesives, various mechanical fasteners, or welding.”

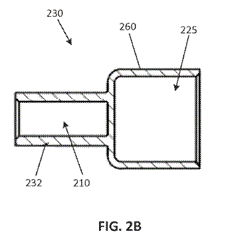

The following is an example of the “machined fuse end cap”:

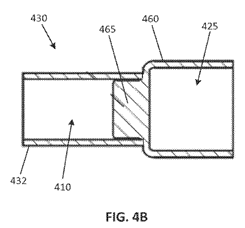

And the following is an example of the “assembled end cap”:

During prosecution, the Examiner issued a restriction requirement stating that each of the three embodiments represented a distinct species. Littlefuse elected to prosecute the species corresponding to the “assembled end cap” embodiment. Claims 8 and 9 directed to the “machined end cap” and the “stamped end cap,” respectively, were then withdrawn. These dependent claims were subject to reinstatement if a generic claim was found to be allowable. Upon a rejection issued by the Examiner, claim 1 was amended to include the “fastening stem” limitation shown above. Amended claim 1 was then allowed and claims 8 and 9 were rejoined since the Examiner concluded that claims 8 and 9 require all the limitations of the allowable claims.

District Court

In the district court, the term “fastening stem” was construed to mean “a stem that attaches or joins other components”; and “a fastening stem that extends from the mounting cuff and into the second cavity of the terminal that receives the conductor” was construed to mean “a stem that extends from the mounting cuff and into the second cavity of the terminal that receives the conductor, and attaches the mounting cuff to the terminal.” The district court further construed claim 1 such that the fuse end cap “is of multi-piece construction” and that claim 1 does not cover a single-piece apparatus. The parties stipulated to non-infringement based on the district court’s construction of claim 1 as covering only a multi-piece apparatus, and Littlefuse appealed the claim construction ruling.

CAFC

The court first explained claim construction principles citing Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (en banc) stating that “A claim term is generally given the meaning that the term would have to a person of ordinary skill in the art in question at the time of the invention” and that “How the term is used in the claims and the specification of the patent is strong evidence of how a person of ordinary skill would understand the term.”

The court further stated that “The structure of the claims is enlightening.” Citing Baxalta Inc. v. Genentech, Inc., 972 F.3d 1341 (Fed. Cir. 2020), the court stated that “By definition, an independent claim is broader than a claim that depends from it, so if a dependent claim reads on a particular embodiment of the claimed invention, the corresponding independent claim must cover that embodiment as well.” The court stated that if this were not the case, then the dependent claim would be meaningless, and a claim construction that leads to that result is generally disfavored. Thus, the court concluded that the recitation of a single-piece apparatus in claims 8 and 9 is persuasive evidence that claim 1 also covers a single-piece apparatus.

The court then explained principles regarding claim-differentiation stating that “the presumption of differentiation in claim scope is not a hard and fast rule” citing Seachange Int’l, Inc. v. C-COR, Inc., 413 F.3d 1361 (Fed. Cir. 2005) and that “any presumption created by the doctrine of claim differentiation will be overcome by a contrary construction dictated by the written description or prosecution history” citing Retractable Techs., Inc. v. Becton, Dickinson, and Co., 653 F.3d 1296 (Fed. Cir. 2011).

Mersen argued that notwithstanding the doctrine of claim differentiation, a construction that renders certain claims superfluous need not be rejected if that construction is consistent with the teachings of the specification citing Marine Polymer Technologies, Inc. v. HenCon, Inc., 672 F.3d 1350 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (en banc). However, the court stated that Littlefuse’s construction is supported by the specification. The court further stated that Mersen’s construction “would not merely render the dependent claims superfluous, but would mean that those claims would have no scope at all, a result that should be avoided when possible.”

The court pointed out that the district court recognized the inconsistency between its construction of claim 1 as covering only a multi-piece apparatus and the recitation of a single-piece apparatus in dependent claims 8 and 9. The district court concluded that the Examiner’s rejoinder of those dependent claims was a mistake. However, the CAFC said that the record in this case does not support the district court’s conclusion. The CAFC agreed with the Examiner that the dependent claims “require all the limitations of the … allowable claims” since the independent claims are not limited to a multi-piece construction and “the dependent claims form a coherent invention in that they each recite a fuse end cap that comprises a mounting cuff, a terminal, and a fastening stem.

The court also addressed the specification which only refers to a “fastening stem” with respect to the “assembled end cap” embodiment, which is a multi-piece apparatus. But the court said that “courts ordinarily should not limit the claimed invention to preferred embodiments or specific examples in the specification.” The court pointed out that the specification does not state that a fastening stem cannot be present in a single-piece apparatus and “one can envision a stem that projects from the side of the mounting cuff even in an embodiment in which the fuse end cap is formed from a single piece of material.”

The court concluded that the construction of “fastening stem” that is most consistent with the claims, specification, and prosecution history is a construction that includes a multi-piece end cap as well as a single-piece end cap. Thus, the court vacated the district court’s judgment of non-infringement and remanded.

Comments

Claim differentiation can be a useful tool for providing broader claim scope to independent claims. Thus, when drafting patent applications, it is a good idea to include various dependent claims.

Also, when faced with a restriction requirement due to distinct species and upon allowance of some claims, make sure to review whether other claims can be rejoined. In this case, the fact that the Examiner rejoined some species claims as being covered by a generic independent claim helped persuade the CAFC to provide a broader construction of the independent claim.

APPLE MAKES ROTTEN CONVINCING THAT THE PTAB CANNOT CONSTRUE CLAIMS PROPERLY

Michael Caridi | April 7, 2022

Apple, Inc vs MPH Technologies, OY

Decided: March 9, 2022

MOORE, Chief Judge, PROST and TARANTO. Opinion by Moore.

Summary:

Apple appealed losses on 3 IPRs attempting to convince the CAFC that the PTAB had misconstrued numerous dependent claims for a myriad of reasons. The CAFC sided with the Board on all counts, in general showing deference to the PTAB and its ability to properly interpret claims.

Background:

Apple appealed from 3 IPRs wherein the PTAB had held Apple failed to show claims 2, 4, 9, and 11 of U.S. Patent No. 9,712,494; claims 7–9 of U.S. Patent No. 9,712,502; and claims 3, 5, 10, and 12–16 of U.S. Patent No. 9,838,362 would have been obvious. Apple’s IPR petitions relied primarily on a combination of Request for Comments 3104 (RFC3104) and U.S. Patent No. 7,032,242 (Grabelsky).

The patents disclose a method for secure forwarding of a message from a first computer to a second computer via an intermediate computer in a telecommunication network in a manner that allowed for high speed with maintained security.

The claims of the ’494 and ’362 patents cover the intermediate computer. Claim 1 of the ’494 patent was used as the representative independent claim for the patents:

1. An intermediate computer for secure forwarding of messages in a telecommunication network, comprising:

an intermediate computer configured to connect to a telecommunication network;

the intermediate computer configured to be assigned with a first network address in the telecommunication network;

the intermediate computer configured to receive from a mobile computer a secure message sent to the first network address having an encrypted data payload of a message and a unique identity, the data payload encrypted with a cryptographic key derived from a key exchange protocol;

the intermediate computer configured to read the unique identity from the secure message sent to the first network address; and

the intermediate computer configured to access a translation table, to find a destination address from the translation table using the unique identity, and to securely forward the encrypted data payload to the destination address using a network address of the intermediate computer as a source address of a forwarded message containing the encrypted data payload wherein the intermediate computer does not have the cryptographic key to decrypt the encrypted data payload.

The ’502 patent claims the mobile computer that sends the secure message to the intermediate computer.

Decision:

The Court first looked at dependent claim 11 of the ’494 patent and dependent claim 12 of the ’362 patent requirement that “the source address of the forwarded message is the same as the first network address.”

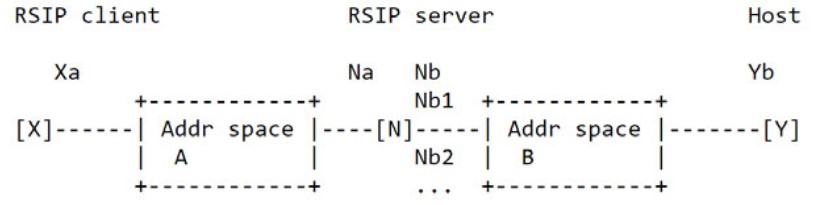

Apple had asserted RFC3104 disclosed this aspect of the claims. Specifically, RFC3104 discloses a model wherein an RSIP server examines a packet sent by Y destined for X. “X and Y belong to different address spaces A and B, respectively, and N is an [intermediate] RSIP server.” N has two addresses: Na on address space A and Nb on address space B, which are different. Apple asserted the message sent from Y to X is received by RSIP server N on the Nb interface and then must be sent to Na before being forwarded to X.

The model topography for RFC3104 is illustrated as:

In light thereof, Apple asserted that because the intermediate computer sends the message from Nb to Na before forwarding it to X, Na is both a first network address and the source address of the forwarded message. That the message was not sent directly to Na, Apple claimed, was of no import given the claim language. The Board had disagreed and found there was no record evidence that the mobile computer sent the message directly to Na.

In the appeal, Apple argued the Board misconstrued the claims to require that the mobile computer send the secure message directly to the intermediate computer. Rather, Apple asserted, the mobile computer need not send the message to the first network address so long as the message is sent there eventually. Specifically, Apple emphasized that the PTAB’s construction is inconsistent with the phrase “intermediate computer configured to receive from a mobile computer a secure message sent to the first network address” in claim 1 of the ’494 patent, upon which claim 11 depends.

The Court construed the plain meaning of “intermediate computer configured to receive from a mobile computer a secure message sent to the first network address” requires the mobile computer to send the message to the first network address. The phrase identifies the sender (i.e., the mobile computer) and the destination (i.e., the first network address). The CAFC maintained that the proximity of the concepts links them together, such that a natural reading of the phrase conveys the mobile computer sends the secure message to the first network address. Thus the CAC agreed with the PTAB that the plain language establishes direct sending.

The Court reenforced their holding by looking to the written description as confirming this plain meaning. Specifically, they noted it describes how the mobile computer forms the secure message with “the destination address . . . of the intermediate computer.” The mobile computer then sends the message to that address. There is no passthrough destination address in the intermediate computer that the secure message is sent to before the first destination address. Accordingly, like the claim language, the written description describes the secure message as sent from the mobile computer directly to the first destination address.

Second, the CAFC examined dependent claim 4 of the ’494 patent is similar to claim 5 of the ’362 patent. Claim 4 of the ‘494 recites:

…wherein the translation table includes two partitions, the first partition containing information fields related to the connection over which the secure message is sent to the first network address, the second partition containing information fields related to the connection over which the forwarded encrypted data payload is sent to the destination address. (emphasis added in opinion).

The Board had interpreted “information fields” in this claim to require “two or more fields.” However, Apple’s obviousness argument relied on Figure 21 of Grabelsky, which disclosed a partition with only a single field. Therefore, the Board found Apple failed to show the combination taught this limitation. Moreover, the Board found Apple failed to show a motivation to modify the combination to use multiple fields.

On claim construction, Apple contended there is a presumption that a plural term covers one or more items. Apple maintained that patentees can overcome that presumption by using a word, like “plurality”, that clearly requires more than one item.

The Court found that Apple misstated the law. In accordance with common English usage, the Court presumes a plural term refers to two or more items. And found that this is simply an application of the general rule that claim terms are usually given their plain and ordinary meaning.

The Court also noted that there is nothing in the written description providing any significance to using a plurality of information fields in a partition. The CAFC therefore found that absent any contrary intrinsic evidence, the Board correctly held that fields referred to more than one field.

Third, the Court looked to Claim 2 of the ’494 patent and claim 3 of the ’362 patent. Claim 2 of the ‘494 states:

…wherein the intermediate computer is further configured to substitute the unique identity read from the secure message with another unique identity prior to forwarding the encrypted data payload. (emphasis added in opinion).

The Board construed the word “substitute” to require “changing or modifying, not merely adding to.” Because it determined that RFC3104 merely involved “adding to” the unique identity, the Board found Apple had failed to show RFC3104 taught this limitation. The Board expressly addressed Apple’s argument from the hearing that “adding the header is the same as replacing the header because at the end of the day you have a different header than what you had before, a completely different header.” The Board disagreed with Apple and construed “substitute” to mean “changing, replacing, or modifying, not merely adding,” and observed that this construction disposed of Apple’s position.

The CAFC found no misconstruction by the PTAB with this interpretation. Moreover, the Court noted tat substantial evidence supports the Board’s finding that Apple failed to show a motivation to modify the prior art combination to include substitution. Apple relied solely on its expert’s contrary testimony, which the Court found the Board had properly disregarded as conclusory.

Fourth, the Court reviewed the PTAB’s interpretation of claim 9 of the ’494 patent, similar to claim 10 of the ’362 patent. Claim 9 of the ‘494 states:

…wherein the intermediate computer is configured to modify the translation table entry address fields in response to a signaling message sent from the mobile computer when the mobile computer changes its address such that the intermediate computer can know that the address of the mobile computer is changed. (emphasis added in opinion).

Apple argued that establishing a secure authorization in RFC3104 includes creating a new table entry address field as required by the claim. The Board disagreed, reasoning that “modify[ing] the translation table entry address fields” requires having existing address fields when the mobile computer changes its address. Accordingly, it found Apple failed to how the combination taught this limitation. Apple argued before the CAFC that the “configured to modify the translation table entry address fields” limitation is purely functional and, thus, covers any embodiment that results in a table with different address fields, including new address fields. The CAFC disagreed, finding as the Board held, the plain meaning of “modify[ing] the translation table entry address fields” requires having existing address fields in the translation table to modify.

Specifically, the Court reasoned that the surrounding language showing the modification occurs “when the mobile computer changes its address such that the intermediate computer can know that the address of the mobile computer is changed” further supports the existence of an address field prior to modification. Thus, the CAFC found that the limitation does not merely claim a result; it recites an operation of the intermediate computer that requires an existing address field.

Fifth and final, the Court reviewed claim 7 of the ’502 patent which recites:

…wherein the computer is configured to send a signaling message to the intermediate computer when the computer changes its address such that the intermediate computer can know that the address of the computer is changed.

The Court noted that the RFC3104 disclosed an ASSIGN_REQUEST_RSIPSEC message that requests an IP address assignment. Apple argued that, when a computer moves to a new address, the computer uses this message as part of establishing a secure connection and, in the process, the intermediate computer knows the address has been changed. The Board had found that the message was not used to signal address changes. Accordingly, the Board determined that Apple had failed to show that the intermediate computer knows that the address is changed, as required by the claim language. Apple reprises its arguments, which the Board had rejected.

The CAFC noted that claims 7–9 of the ’502 patent require a computer to send a message to the intermediate computer “such that the intermediate computer can know that the address of the computer is changed.” The Court affirmed the Board’s contrary finding was supported by substantial evidence, including MPH’s expert testimony and RFC3104 itself. MPH’s expert testified that a skilled artisan would not have understood the relevant disclosure in RFC3104 to teach any signal address changes. Agreeing with the PTAB, the Court found that the relevant disclosure in RFC3104 relates to establishing an RSIP-IPSec session, not to signal address changes. Hence, they saw no reason why the Board was required to equate communicating a new address and signaling an address change. They therefore concluded that substantial evidence supports the Board’s finding.

In the end, the CAFC affirmed all of the Board’s final written decisions holding that claims 2, 4, 9, and 11 of the ’494 patent; claims 7–9 of the ’502 patent; and claims 3, 5, 10, and 12–16 of the ’362 patent would not have been obvious.

Take away:

Although the CAFC reviews claim construction and the Board’s legal conclusions of obviousness de novo, they are inclined toward giving deference to the PTAB. Caution should be taken in attempting to convince the CAFC that the Board has misconstrued claims unless there is a clear showing that the Board did not follow the Phillips standard (Claim terms are given their plain and ordinary meaning, which is the meaning one of ordinary skill in the art would ascribe to a term when read in the context of the claim, specification, and prosecution history).

Got A Lot To Say? Unfortunately, CAFC Affirm A Word Limit Will Not Prevent Estoppel Under 35 USC §315(e)(1)

Adele Critchley | April 1, 2022

Intuitive Surgical, Inc., vs., Ethicon LLC and Andrew Hirshfeld, performing the functions and duties of the undersecretary of commerce for Intellectual Property and Director of the USPTO.

Decided: February 11, 2022

Circuit Judges O’Malley (author), Clevenger and Stoll.

Summary:

The CAFC affirmed a decision of the Patent Trial and Appeal board (PTAB) terminating Intuitive’ s participation in an inter partes review (IPR) based on the estoppel provision of 35 U.S.C. §315(e)(1).

35 U.S.C. §315(e)(1) states that “[t]he petitioner in an inter partes review of a claim in a patent under this chapter that results in a final written decision . . . may not request or maintain a proceeding before the Office with respect to that claim on any ground that the petitioner raised or reasonably could have raised during that inter partes review.” 35 U.S.C. § 315(e)(1).

On June 14, 2018, Intuitive simultaneously filed three IPR petitions against a Patent owned by Ethicon (U.S. Patent No. 8,479,969), each challenging the patentability of claims 24 to 26 but each based upon a different combination of prior art references. Despite being filed at the same time, one of the three petitions was instituted one month after the other two. Continuing on this varied timeline, the PTAB issued final written decisions in the two petitions that instituted earliest. As a result, the PTAB found that Intuitive was estopped from participating as a party in the pending third petition. The PTAB concluded that §315(e)(1) did not preclude estoppel from applying where simultaneous petitions were filed by the same petitioner on the same claim.

Intuitive appealed. Intuitive argued that the 14000-word page limit for IPR petitions meant they could not reasonable have raised the prior art from the third and pending petition in in the same petition as the others. Intuitive argued that §315(e)(1) estoppel should not apply to simultaneously filed petitions. Intuitive argues, moreover, that it may appeal the merits of the Board’s final written decision on the patentability of the claims because, “even if the Board’s estoppel decision is not erroneous, Intuitive was once “a party to an inter partes review” and is dissatisfied with the Board’s final decision within the meaning of § 319.” (Only a party to an IPR may appeal a Board’s final written decision. See 35 U.S.C. § 141(c) (“A party to an inter partes review . . . who is dissatisfied with the final written decision . . . may appeal.”). Section 319 of Title 35 repeats that limitation).

The CAFC disagreed arguing that the plain language of §315(e)(1) is clear. §315(e)(1) estops a petitioner as to invalidity grounds for an asserted claim that it failed to raise but “reasonably could have raised” in an earlier decided IPR, regardless of whether the petitions were simultaneously filed and regardless of the reasons for their separate filing. The CAFC reasoned that since Intuitive filed all three petitions, it follows that they actually knew of all the prior art cited and so could have reasonably raised its grounds in the third petition in either of the first two petitions. First, the CAFC concludes that the petitions could have been written “more concisely” in order to fit within two petitions. Second, the CAFC noted that Intuitive had alternative avenues, including (i) seeking to consolidate multiple proceedings challenging the same patent (see 35 U.S.C. § 315(d) (permitting the Director to consolidate separate IPRs challenging the same patent)); or (ii) filing multiple petitions where each petition focuses on a separate, manageable subset of the claims to be challenged—as opposed to subsets of grounds—as § 315(e)(1) estoppel applies on a claim-by-claim basis.

Take-away:

- To avoid estoppel under 315(e)(1), when it is not possible to draft IPR petitions concisely, consider multiple petitions each focused on a separate manageable subset of claims or seek consolidation.

Forum Selection Clause Can Prevent IPR Fights

Sung-Hoon Kim | March 25, 2022

Nippon Shinyaku Co., Ltd. v. Sarepta Therapeutics, Inc.

Decided on February 8, 2022

Lourie (author), Newman, and Stoll

Summary:

The Federal Circuit reversed the district decision’s denial of a preliminary injunction for Nippon Shinyaku because its agreement with Sarepta was clear to exclude filing IPR petitions, and Sarepta’s filing of IPR petitions clearly breached the agreement with Nippon Shinyaku.

Details:

On June 1, 2020, Nippon Shinyaku and Sarepta Therapeutics, Inc. (“Sarepta”) executed a Mutual Confidentiality Agreement (“MCA”) to enter into discussions for a potential business relationship relating to therapies for the treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (“DMD”).

Section 6 of the MCA included a mutual covenant not to sue during the Covenant Term[1]:

shall not directly or indirectly assert or file any legal or equitable cause of action, suit or claim or otherwise initiate any litigation or other form of legal or administrative proceeding against the other Party . . . in any jurisdiction in the United States or Japan of or concerning intellectual property in the field of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.

Section 6 further stated:

For clarity, this covenant not to sue includes, but is not limited to, patent infringement litigations, declaratory judgment actions, patent validity challenges before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office or Japanese Patent Office, and reexamination proceedings before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office . . . .

After the expiration of the Covenant Term, the forum selection clause in Section 10 of the MCA is applied:

[T]he Parties agree that all Potential Actions arising under U.S. law relating to patent infringement or invalidity, and filed within two (2) years of the end of the Covenant Term, shall be filed in the United States District Court for the District of Delaware and that neither Party will contest personal jurisdiction or venue in the District of Delaware and that neither Party will seek to transfer the Potential Actions on the ground of forum non conveniens.

Here, “Potential Actions” is defined as “any patent or other intellectual property disputes between [Nippon Shinyaku] and Sarepta, or their Affiliates, other than the EP Oppositions or JP Actions, filed with a court or administrative agency prior to or after the Effective Date in the United States, Europe, Japan or other countries in connection with the Parties’ development and commercialization of therapies for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.”

The Covenant Term ended on June 21, 2021, at which point the two-year forum selection took effect. On June 21, 2021, Sarepta filed seven petitions for IPR.

District Court

On July 13, 2021, Nippon Shinyaku filed a complaint in the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware asserting claims against Sarepta for breach of contract, among other things. Nippon Shinyaku alleged that Sarepta breached the MCA by filing seven IPR petitions. Nippon Shinyaku filed a motion for a preliminary injunction to enjoin Sarepta from proceeding with IPR petitions.

On September 24, 2021, the district court denied Nippon Shinyaku’s motion for a preliminary injunction and issued its memorandum order with the following reasons:

- There would be a “tension” that would exist between Sections 6 and 10 if the forum selection clauses were interpreted to exclude IPRs.

- Section 10 applies only to cases filed in federal court.

- Practical effects of interpreting Section 10 as excluding IPRs for two years following the Covent Term.

- Finally, Nippon Shinyaku did not meet its burden on second (suffer irreparable harm), third (balance of hardship), fourth (public interest) PI factors in order to obtain a preliminary injunction.

Federal Circuit

The CAFC reviewed a denial of a preliminary injunction using the law of the regional circuit (Third Circuit) for abuse of discretion.

The CAFC focused on the court’s interpretation of the MCA.

Based on the plain language of the forum selection clause in Section 10 of the MCA, the CAFC held that the forum selection clause is unambiguous because the definition of “Potential Actions” includes “patent or other intellectual property disputes… filed with a court or administrative agency,” and the district court acknowledged that the definition of Potential Actions literally encompasses IPRs.

The CAFC held that under the plain language of Section 10, Sarepta should have brought all disputes regarding the invalidity of Nippon Shinyaku’s patents in the District of Delaware.

The CAFC rejected Sarepta’s argument that IPR petitions must be filed in the federal district court in Delaware. Also, the CAFC held that there is no conflict or tension between Sections 6 and 10. The CAFC noted that this reflects harmony, not tension between two sections and this framework is “entirely consistent with our interpretation of the plain meaning of the forum selection clause.”

Finally, the CAFC noted that other factors of a preliminary injunction favored Nippon Shinyaku. As for irreparable harm, the CAFC agreed with Nippon Shinyaku’s argument that they would be “deprived of its bargained-for choice of forum and forced to litigate its patent rights in multiple jurisdictions.” As for balance of hardships, Nippon Shinyaku would suffer the irreparable harm, and Sarepta would potentially get multiple chances at a forum it bargained away. As for public interest, the CAFC rejected any notion that there is “anything unfair about holding Sarepta to its bargain.”

Therefore, the CAFC reversed the decision of the district court and remanded for entry of a preliminary injunction.

Takeaway:

- Companies will need to be extra careful when drafting nondisclosure and joint development agreements now that the CAFC held that clauses in those agreements can give up right to file challenges at the PTAB.

- Contracts can be used to waive the right to AIA review.

- This is a cautionary tale for attorneys to start paying attention to boilerplate parts of contracts.

- This is the first time that the CAFC held that it is not again the public interest to have forum selection clauses that exclude PTAB proceedings.

[1] Covenant Term is defined as “the time period commencing on the Effective Date and ending upon twenty (20) days after the earlier of: (i) the expiration of the Term, or (ii) the effective date of termination.”

Tags: contract > IPR > Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) > preliminary injunction