Aruba Bet Plateforme : Votre Destination de Gaming en Ligne fiable de Référence

Sung-Hoon Kim | February 13, 2026

Table des matières

- Nos Aventures de Jeu Sur-mesure

- Sécurité et Clarté Garanties

- Options de Paiement Flexibles

- Avantages Exclusives pour Nos fidèles Joueurs

- Support Professionnelle 24/7

Des véritables Sessions de Gaming Adaptées

Notre plateforme casino propose bien davantage qu’une banale ordinaire plateforme de jeu. Avec https://aruba-bet.com/, nous-mêmes avons spécialement créé un univers où chaque partie de divertissement représente une expérience unique. Notre catalogue inclut plus encore de 2500 remarquables titres rigoureusement choisis, variant des machines à sous modernes modernes aux classiques de cartes classiques. Cette impressionnante diversité offre à n’importe quel utilisateur de dénicher parfaitement ce qu’il rêve, que vous soyez sois amateur de tactique ou de hasard absolue.

Les innovations que nous-mêmes utilisons garantissent une fluidité optimale sur tous vos dispositifs. Nos partenariats avec les meilleurs créateurs les plus réputés de l’industrie garantissent des rendus superbes et des mécaniques de gameplay révolutionnaires. Chacun des divertissement est vérifié pour offrir un ratio de redistribution joueur maximal, conformément aux règles internationaux de ce domaine du gaming en ligne certifié.

Nos meilleures Catégories Principales

- Slots à Sous à Jackpot – Jackpots dépassant souvent des millions EUR avec des paris ajustées à tous types de ces moyens

- Tables de jeu en Direct Live – Dealers experts streamés depuis des studios ultra haute qualité pour une immersion maximale

- Parties Rapides – Sessions courtes et énergiques idéales pour vos périodes de détente

- Événements Uniques – Challenges chaque semaine avec tableaux en temps strictement réel et gains substantielles

- Gamme Rétro – Éditions modernisées des meilleurs mythiques plébiscités depuis des générations

Protection et Transparence Garanties

Notre établissement fonctionne sous une certification légale émise par l’organisme de Curaçao (numéro de autorisation 8048/JAZ), garantissant le respect des règles globales les plus particulièrement strictes. Cette précieuse homologation impose des vérifications fréquents de nos systèmes de génération aléatoire et de nos rigoureux processus transactionnels. Notre plateforme utilisons le protocole de chiffrement SSL sécurisé 256 bits, équivalent à celui-là adopté par les grandes banques bancaires globales.

Notre sécurisation des renseignements privées représente notre première exigence totale. Nos protégés infrastructures sont hébergés dans des installations homologués ISO 27001, avec des sauvegardes journalières redondantes. Aucune info ne sera partagée avec des tiers sans consentement formel, suivant au RGPD de l’UE.

Méthodes de Paiement Variées

| Cartes de paiement | 10€ | 1 à 3 jours ouvrés | Sans frais |

| Portefeuilles Digitaux | 10€ | Immédiat – 24h | Gratuit |

| Transfert Bancaire classique | 50€ | 3 à 5 jours utiles ouvrés | 0€ |

| Cryptomonnaies | 20€ | 1 à 2 h | Gratuit |

Ce établissement procède à l’ensemble des ces transferts avec la plus stricte rigueur. Vos demandes de récupération sont contrôlées dans un laps de temps maximal de 24 petites h pendant les jours de travail ouvrables. Nous-mêmes n’appliquons aucune plafond hebdomadaire aux transferts pour nos précieux membres assidus, privilégiant ainsi la souplesse économique.

Bonus Exclusives pour Nos fidèles Membres

Le système de loyauté que nous-mêmes avons soigneusement développé en place récompense la fidélité de chaque joueur. Dès même votre inscription, tu avez accès à un plan progressif contenant 6 paliers différents. Chacun des niveau débloque des avantages additionnels : multiplicateurs de gains, conseiller de profil personnalisé, accès à des événements VIP.

Avantages Chaque mois

- Remboursement Automatique – Restitution de 10 % à vingt pour cent sur les déficits par semaine suivant votre standing VIP

- Spins Gratuits Réguliers – Octroi chaque semaine sur les dernières nouveaux jeux et jeux populaires sans exigences de pari excessive

- Cadeau Birthday – Présent customisé calculé selon votre activité annuelle

- Dépôts Bonifiées – Pourcentages augmentés pouvant atteindre 75% sur certains versements mensuels

Service client Dédiée 24/7

Notre compétente brigade multilingue reste disponible sans interruption via plusieurs moyens. Le fameux chat live en temps réel propose des solutions en pas plus de deux petites minutes en général. Pour traiter vos demandes plus élaborées, notre réactif service email réagit sous six petites h maximum. Nous-mêmes avons aussi de plus développé une section de ressources complète traitant plus de 150 différentes questions usuelles, fréquemment actualisée.

Les conseillers qui composent notre professionnelle brigade suivent des formations permanentes sur nos produits et les normes. Cette précieuse maîtrise leur autorise de traiter efficacement tous les genres de requêtes, que celles-ci impliquent ces aspects tech, monétaires ou gaming. Chaque échange est enregistrée pour procurer un tracking idéal de ton parcours chez ce casino.

Notre équipe plaçons constamment dans l’optimisation de nos prestations. Vos retours de nos fidèles utilisateurs orientent immédiatement nos prochains évolutions prochains, puisque votre plaisir définit notre propre réussite à long terme.

Oficjalna strona internetowa Vavada casino PL

Sung-Hoon Kim | January 22, 2026

Oficjalna strona internetowa Vavada casino PL

Oficjalna strona kasyna Vavada to platforma hazardowa online, którą można odwiedzić na głównych domenach takich jak Vavada.com albo mirror-stronach dedykowanych Polsce i innym krajom europejskim. Serwis istnieje od 2017 roku i zdobył szeroką bazę graczy dzięki ogromnej bibliotece gier, licznym promocjom i prostemu systemowi rejestracji. Kasyno działa na licencji z Curacao – oznacza to, że jest formalnie zarejestrowane i podlega zasadom regulacyjnym tej jurysdykcji, ale nie ma szczególnego nadzoru ze strony europejskich organów stricte hazardowych.

Strona jest dostępna w wielu językach, w tym po polsku, i oferuje możliwość szybkiego przejścia przez proces logowania lub rejestracji. Interfejs użytkownika jest podzielony na wygodne sekcje – konto gracza, portfel z historią transakcji i metodami płatności, sekcja bonusów oraz status lojalnościowy gracza. W panelu konta znajdziesz również komunikaty od kasyna oraz informacje o aktywnych promocjach.

Platforma umożliwia grę zarówno na komputerach, jak i urządzeniach mobilnych – bez konieczności instalowania osobnej aplikacji, ponieważ mobilna wersja strony oferuje funkcjonalność pełną jak na desktopie. Dodatkowo kasyno obsługuje wiele walut i ponad 17 metod płatności, co daje dużą elastyczność osobom, które preferują różne sposoby depozytów lub wypłat.

Kolekcja gier

Gdy spojrzysz na kolekcję gier dostępnych w Vavada kasyno, to pierwsze, co uderza – ogrom i różnorodność, która dosłownie zasypuje nowego gracza już na etapie przeglądania katalogu. Oficjalne dane mówią o ponad 4 500 tytułach z całego świata – od automatów typu slot po stoły z żywymi krupierami i klasyczne gry stołowe.

Sloty – serce kolekcji

Sloty stanowią lwią część całej biblioteki – często ponad 90% wszystkich dostępnych gier. Znajdziesz tu klasyczne automaty owocowe, nowoczesne video sloty z wieloma liniami wygranych oraz tytuły typu Megaways. Popularne przykłady gier to m.in. Sweet Bonanza, Book of Ra, Gates of Olympus, The Dog House czy Big Bass Bonanza – każda z nich ma własne unikalne bonusy w grze, darmowe rundy i mechaniki, które porywają uwagę.

Gry stołowe i karciane

Poza slotami, Vavada oferuje ruletkę, blackjacka, baccarat, a także inne klasyki stołowe. To mniej rozbudowana sekcja niż sloty, ale wciąż stanowi solidną opcję dla osób, które wolą strategiczną rozgrywkę nad prostym kręceniem bębnów.

Live casino – emocje jak w realu

Jeżeli chcesz poczuć atmosferę prawdziwego kasyna, dostępna jest sekcja live dealer, gdzie gra toczy się na żywo, a profesjonalni krupierzy prowadzą ruletkę, blackjacka i inne rozgrywki w czasie rzeczywistym. Transmisje odbywają się 24/7 i bywają popularne w godzinach wieczornych, gdy aktywność graczy rośnie.

Dostawcy oprogramowania

Kasyno współpracuje z dużą liczbą renomowanych dostawców gier – w katalogu pojawiają się tacy jak Pragmatic Play, Evolution Gaming, Relax Gaming, Push Gaming, NetEnt, Play’n GO, ELK Studios i wielu innych. Dzięki temu tytuły są nie tylko różnorodne, ale często aktualizowane i technicznie dopracowane.

Bonusy i promocje

System bonusów w Vavada casino online to coś, co przyciąga wiele osób – i to już od pierwszego kontaktu z kasynem. Oferta jest złożona, obejmuje bonusy powitalne, darmowe spiny, promocje cykliczne i elementy programu lojalnościowego.

Bonus powitalny

Nowi gracze otrzymują pakiet powitalny – klasyczny zestaw to 100% bonus od pierwszej wpłaty z możliwością zwiększenia salda nawet do 1000 $ lub równowartości w innej walucie oraz dodatkowe 100 darmowych spinów do wykorzystania na konkretnych slotach. Minimalna wpłata, aby aktywować ten bonus, to zazwyczaj 1 EUR / 1 $.

Warunki obrotu (czyli tzw. wager) przy bonusie depozytowym zwykle wynoszą x35, co oznacza, że środki bonusowe trzeba obrócić 35 razy przed możliwością wypłaty wygranych z bonusu. W przypadku darmowych spinów również obowiązują warunki obrotu, często x20-x40 zależnie od promocji i zasad konkretnej nagrody.

Darmowe spiny i bonus bez depozytu

Oprócz klasycznego pakietu powitalnego, kasyno regularnie oferuje darmowe spiny bez depozytu – np. 100 darmowych spinów za samo założenie konta, które można wykorzystać na wybranych automatach, często z limitem na maksymalną wysokość wypłaty wygranych z tych spinów.

Cashback i promocje stałe

Vavada casino ma też mechanizm cashback, najczęściej na miesięcznej zasadzie – gracze mogą odzyskać część przegranych środków (np. 10% różnicy między łącznymi zakładami a wygranymi) w formie bonusowej.

Program VIP i turnieje

Platforma posiada także program lojalnościowy z kilkoma poziomami – im więcej grasz i obracasz depozytami, tym wyższe statusy i lepsze bonusy możesz uzyskać, w tym wyższe limity wypłat lub indywidualne oferty. Regularnie organizowane są też turnieje z nagrodami, w których pula nagród może być znaczna.

Metody płatności i wypłaty środków

Jednym z kluczowych aspektów każdego kasyna online jest wygoda i bezpieczeństwo transakcji finansowych. Vavada casino oferuje ponad 17 metod płatności, które obejmują zarówno tradycyjne karty bankowe Visa i Mastercard, jak i nowoczesne portfele elektroniczne takie jak Skrill, Neteller czy ecoPayz. Dla graczy preferujących kryptowaluty dostępne są również opcje depozytów i wypłat w Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin oraz innych popularnych walutach cyfrowych, co zapewnia dodatkową warstwę anonimowości i szybkości przetwarzania transakcji.

Minimalna kwota depozytu jest zazwyczaj bardzo niska – często wynosi zaledwie 1 EUR lub równowartość w innej walucie, co sprawia, że platforma jest dostępna nawet dla graczy z niewielkim budżetem. Jeśli chodzi o wypłaty, kasyno deklaruje czas przetwarzania od kilku minut do 24 godzin w zależności od wybranej metody, choć w praktyce czas ten może się wydłużyć ze względu na procesy weryfikacyjne, szczególnie przy pierwszych wypłatach lub wyższych kwotach.

Bezpieczeństwo i odpowiedzialna gra

Vavada stosuje standardowe protokoły szyfrowania SSL, które chronią dane osobowe graczy oraz informacje finansowe podczas przesyłania ich przez internet. Kasyno wymaga również weryfikacji tożsamości (KYC) przed dokonaniem pierwszej wypłaty – gracze muszą przesłać kopię dokumentu tożsamości oraz potwierdzenie adresu zamieszkania, co jest standardową praktyką w branży hazardowej online i ma na celu zapobieganie praniu pieniędzy oraz oszustwom.

Platforma udostępnia również narzędzia odpowiedzialnej gry, takie jak możliwość ustawienia limitów depozytów dziennych, tygodniowych lub miesięcznych, a także opcję samowyłączenia konta na określony czas. Są to ważne mechanizmy dla graczy, którzy chcą kontrolować swoje wydatki i unikać problematycznych zachowań hazardowych. Warto jednak pamiętać, że licencja z Curacao nie zapewnia takiego samego poziomu ochrony konsumenta jak licencje wydawane przez europejskie organy regulacyjne, takie jak Malta Gaming Authority czy UK Gambling Commission.

Obsługa klienta

Kasyno Vavada oferuje wsparcie techniczne i pomoc dla graczy przez całą dobę za pośrednictwem czatu na żywo, który jest dostępny bezpośrednio na stronie internetowej. Alternatywnie gracze mogą skontaktować się z zespołem obsługi klienta przez email. Czas odpowiedzi na czacie na żywo jest zazwyczaj krótki – kilka minut w godzinach szczytu – natomiast odpowiedzi na wiadomości email mogą zająć do 24 godzin. Obsługa jest dostępna w kilku językach, co ułatwia komunikację graczom z różnych krajów. Warto podkreślić, że jakość obsługi klienta jest istotnym czynnikiem przy wyborze kasyna, ponieważ szybka i kompetentna pomoc może znacząco wpłynąć na ogólne doświadczenie użytkownika, szczególnie w przypadku problemów z transakcjami lub weryfikacją konta.

If It Isn’t The Same, It’s Different!

Adele Critchley | December 4, 2025

MERCK SERONO S.A., Appellant v. HOPEWELL PHARMA VENTURES, INC., (Presidential)

Date of Decision: October 30, 2025

Panel: Before HUGHES, LINN, and CUNNINGHAM, Circuit Judges. LINN, Circuit Judge.

Summary:

Merck Serono S.A. (“Merck”) appeals the determinations by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) in two consolidated inter partes reviews (“IPR”). In this case, the Board held several claims of Merck’s U.S. Patent No. 7,713,947 (“’947 patent”) and U.S. Patent No. 8,377,903 (“’903 patent”) unpatentable as obvious over a combination of Bodor and Stelmasiak. The Patents in question related to oral formulations of cladribine to treat MS.

In 2002, Serono partnered with IVAX Corporation (“Ivax”) to develop oral cladribine to treat MS. Serono was acquired by Merck in 2006. Under their joint research agreement, Merck would “‘conduct clinical trials’ to determine ‘the dose, safety, and/or efficacy’” of cladribine oral tablets, and Ivax would “develop an oral dosage formulation of [cladribine] in tablet or capsule form suitable for use in clinical trials and commercial sale.” On March 26, 2004, Ivax employees Drs. Bodor and Dandiker filed the Bodor international patent application (the primary reference used by Hopewell here). The application was published less than one year before the effective filing date of the patents in-suit, which were each filed December 22, 2004. Both patents list as inventors: Drs. De Luca, Ythier, Munafo, and Lopez Bresnahan (collectively, “named inventors”). All four were employees of Serono and, in at least some way, were a part of the development team that developed the claimed oral cladribine regimen back in 2002 (as evidenced by meeting minutes).

Hopewell Pharma Ventures, Inc. (“Hopewell”) filed two IPRs, respectively challenging claims of the ’947 patent and the ’903 patent as obvious over Bodor and Stelmasiak. The Board held that all challenged claims were unpatentable as obvious thereover. In doing so, the Board rejected patentee’s legal argument that “a reference’s disclosure of the invention of a subset of inventors is disqualified as prior art against the invention of all the inventors.” Id. at 36 (emphasis in original). The rule of In re Land, 368 F.2d 866 (CCPA 1966), that any difference in the “inventive entity” between the reference disclosure and the challenged claims—whether adding or subtracting inventors—rendered the reference a disclosure “by another” and therefore available as prior art, was affirmed. The Board also found there was insufficient corroboration evidence that De Luca’s contribution provided an inventive contribution found in Bodor, as would be required to exclude the disclosure from the prior ar.

Ultimately the CAFC affirmed the Board’s determinations.

Under pre-AIA § 102(e), a patent is anticipated if “the invention was described in . . . a patent granted on an application for patent by another filed in the United States before the invention by the applicant for patent.” 35 U.S.C. 102(e) (emphasis added).

The question presented to the CAFC in this appeal is “whether and to what extent a disclosure invented by fewer than all the named inventors of a patent may be deemed a disclosure “by another” and thus included in the prior art, or whether the disclosure should properly be treated as “one’s own work” and therefore excluded from the prior art.”

Merck argued for the latter, but the CAFC found for the first.

Merck focuses on the following two sentences in Applied Materials, Inc. v. Gemini Res. Corp., 835 F.2d 279 (Fed. Cir. 1987):

However, the fact that an application has named a different inventive entity than a patent does not necessarily make that patent prior art.

Id. at 281 (citing In re Kaplan, 789 F.2d 1574, 1576 (Fed. Cir. 1986)); Appellant’s Opening Br. 30–31. And:

Even though an application and a patent have been conceived by different inventive entities, if they share one or more persons as joint inventors, the 35 U.S.C. § 102(e) exclusion for a patent granted to ‘another’ is not necessarily satisfied.

Applied Materials, 835 F.2d at 281 (emphasis added); Appellant’s Opening Br. 29.

Merck essentially argued that the Courts have rejected a bright-line rule requiring an identical inventive entity to exclude a reference as not “by another.”

The CAFC held that Merck overreads Applied Materials. The CAFC clarified that the decision did not rely on the fact that two of the three named inventors in the later patent were named in the earlier reference patent. Instead, the decision rested on the fact that the later patent and the earlier reference patent were descendants of the same application. The CAFC emphasized that it is erroneous to place too much reliance on the inventive entity “named” in the earlier reference patent: “[T]he fact that an application has named a different inventive entity than a patent does not necessarily make that patent prior art.” Id. (emphasis added). Instead, like in Land, the key question is whether the disclosure in the earlier reference evidenced knowledge by “another” before the patented invention.

The CAFC stated that:

Our case law—in particular, Land—precludes our adoption of the policy argument presented by Merck. As those cases make clear, for a reference not to be “by another,” and thus unavailable as prior art under pre-AIA § 102(e), the disclosure in the reference must reflect the work of the inventor of the patent in question. That is clear enough when a single inventor is involved. What should also be clear is that when the patented invention is the result of the work of joint inventors, the portions of the reference disclosure relied upon must reflect the collective work of the same inventive entity identified in the patent to be excluded as prior art. That showing may be made by fewer than all the inventors but nonetheless must evince the joint work of them all to avoid being considered a work “by another” under the statute. Any incongruity in the inventive entity between the inventors of a prior reference and the inventors of a patent claim renders the prior disclosure “by another,” regardless of whether inventors are subtracted from or added to the patent.

Here, ultimately, Merck failed to provide sufficient evidence that one of the inventors had made an inventive contribution to the relevant disclosure in Bodor, but even if Merck had shown such a contribution, the evidence did show that Bodor’s inventors had made significant contributions, so the reference would still qualify as “by another”.

Next, Merck next argued that it was “surprised by the Board’s application of the above-discussed rule requiring complete identity of inventive entity because the rule is contrary to several provisions of the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (“MPEP”).”

Merck relies on the following MPEP sections. Appellant’s Opening Br. 34. MPEP § 2132.01:

An inventor’s or at least one joint inventor’s disclosure of his or her own work within the year before the application filing date cannot be used against the application as prior art.

And MPEP § 2136.05(b):

[E]ven if an inventor’s or at least one joint inventor’s work was publicly disclosed prior to the patent application, the inventor’s or at least one joint inventor’s own work may not be used against the application subject to preAIA 35 U.S.C. 102 unless there is a time bar.

Hopewell responded that Merck “did not lack notice of the rule because the MPEP expressly adopts the rule of Land in § 2136.04 (titled “Different Inventive Entity; Meaning of ‘By Another’”)”.

The CAFC agreed with Hopewell. Moreover, the CAFC noted that “To the extent the MPEP describes our case law differently, that interpretation does not control,” but nonetheless failed to agree that the MPEP was different.

Accordingly, the CAFC found that Bodor was proper prior art. Once confirmed, the Court went on to affirm the Board’s determination that the challenged claims were obvious in view of Bodor and Stelmasiak,

Comments:

- The phrase “by another” requires complete identity of the inventive entity to exclude a reference as prior art. In order to disqualify overlapping inventor references, corroborated evidence must be provided that all named inventors contributed to the inventive aspect of prior relevant disclosure. Thus, it is important for inventors working under joint research agreements to keep up-to-date lab and meeting notes that could aid in establishing such corroborated evidence.

- MPEP is not controlling over case law where interpretation is distinct.

when an apparatus claim depends on functioning claim to describe the apparatus, what the device does and how it does it are highly relevant to understanding what the device is

Sung-Hoon Kim | October 22, 2025

ROTHSCHILD CONNECTED DEVICES INNOVATIONS, LLC v. COCA-COLA COMPANY

Date of Decision: October 21, 2025

Before: Prost (author), Lourie, and Stoll

Summary:

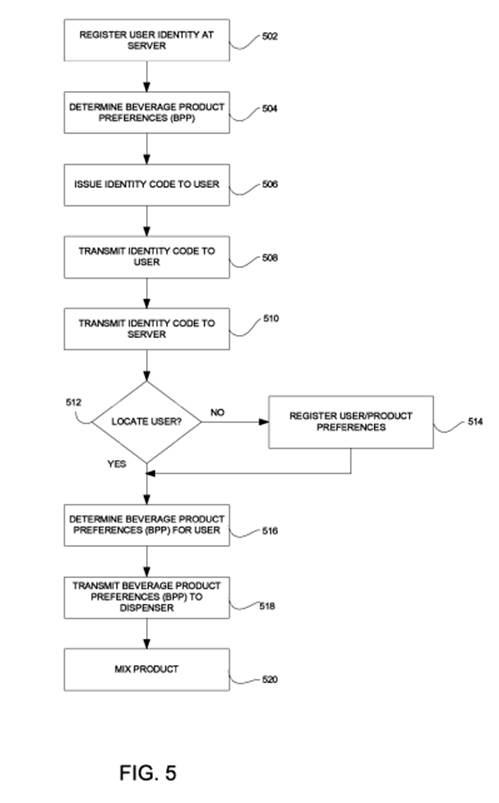

The CAFC agreed with the decision of the district court and affirmed the summary judgement of noninfringement because by looking at the claim language and the specification, the claimed communication module must be configured to perform its steps in the order in which they are written, thereby allowing a narrow claim construction.

Details:

Rothschild Connected Devices Innovations, LLC (“Rothschild”) owns U.S. Patent No. 8,417,377 (“the ’377 patent) and sued Coca-Cola Co. (“Coca-Cola”) for infringing the ’377 patent in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia, which granted summary judgement of noninfringement.

At issue is an independent claim 11, which reads as follows:

A beverage dispenser comprising:

at least one compartment containing an element of a beverage;

at least one valve coupling the at least one compartment to a dispensing section configured to dispense the beverage;

a mixing chamber for mixing the beverage;

a user interface module configured to receive an[] identity of a user and an identifier of the beverage;

a communication module configured to transmit the identity of the user and the identifier of the beverage to a server over a network, receive user generated beverage product preferences based on the identity of the user and the identifier of the beverage from the server and communicat[e] the user generated beverage product preferences to controller; and

the controller coupled to the communication module and configured to actuate the at least one valve to control an amount of the element to be dispensed and to actuate the mixing chamber based on the user gene[r]ated beverage product preferences.

At issue in this appeal is whether the claimed communication module must be configured to perform its steps in the order in which they are written:

(1) “transmit the identity of the user and the identifier of the beverage to a server over a network”;

(2) “receive user generated beverage product preferences based on the identity of the user and the identifier of the beverage from the server”; and

(3) “communicat[e] the user generated beverage product preferences to controller.”

The district court held that the communication module must be configured to perform these steps in that particular order.

The CAFC agreed with the decision of the district court and affirmed the summary judgement of noninfringement.

The CAFC applied a two-part test for determining if steps that do not otherwise recite an order “must nonetheless be performed in the order in which they are written.”

First, the CAFC look at the claim language to determine if, as a matter of logic or grammar, they must be performed in the order written.

Second, if not, the CAFC review the specification to determine whether it directly or implicitly requires such construction.

If not, the sequence in which such steps are written is not a requirement.

In this case, the CAFC held that as a matter of logic or grammar, the communication module must be configured to perform its steps in the order in which they are written – to a server and from the server.

In particular, the CAFC noted that the use of “based on” indicates that the first step precedes the second step.

Furthermore, the CAFC noted that the specification clearly contains language and figures (the below Fig. 5) describing this order and does not contain any suggestion as to Rothschild’s contrary claim interpretation.

Rothschild argued that independent claim 11 is an apparatus claim, and therefore the claim does not require ordered steps (this apparatus claim covers what a device is, not what a device does).

The CAFC noted that while apparatus claims focus on the structure instead of the operation or use, when an apparatus claim depends on functioning claim to describe the apparatus, what the device does and how it does it are “highly relevant to understanding what the device is.”

Accordingly, the CAFC affirmed the summary judgement of noninfringement.

Takeaway:

- Functional claim language matters even for apparatus claims. When an apparatus claim depends on functioning claim to describe the apparatus, what the device does and how it does it are relevant to understanding what the device is.

- In order to obtain broad coverage of functional claim language, the specification should include several embodiments and figures describing broad functional coverage.