No Shapeshifting Claims Through Argument in an IPR

Adele Critchley | December 15, 2022

CUPP Computing AS v. Trend Micro Inc.

Decided: November 16, 2022

Circuit Judges Dyk, Taranto and Stark. Opinion by Dyk.

Summary:

CUPP appeals three inter partes review (“IPR”) decisions of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”), largely due to an issue of claim construction. The three patents at issue are U.S. Patents Nos. 8,631,488 (“’488 patent”), 9,106,683 (“’683 patent”), and 9,843,595 (“’595 patent”). The contested claim construction involves the limitation concerning a “security system processor,” which appears in every independent claim in each of the three patents.

The limitation in question reads in part “the mobile device having a mobile device processor different than the mobile security system processor”.

Trend Micro petitioned the Board for inter partes review of several claims in the ’488, ’683, and ’595 patents, arguing that the claims were unpatentable as obvious over two individual prior art references. CUPP responded that the security system processor limitation required that the security system processor be “remote” from the mobile device processor, and that neither of the cited references disclosed this limitation because both taught a security processor bundled within a mobile device.

The Board instituted review and, in three final written decisions, found all the challenged claims obvious over the prior art. Specifically, the Board held that the challenged claims did not require that the security system processor be remote from the mobile device processor, but merely that the mobile device has a mobile device processor different than the mobile security system processor.

That is, the fact that the security system processor is “different” than the mobile device processor does not suggest that the two processors are remote from one another. Rather, citing Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, the Board and the CAFC noted that the ordinary meaning of “different” is simply “dissimilar.” The CAFC further noted that CUPP had given no reason to apply a more specialized meaning to the word.

Furthermore, the CAFC drew support from the specification of each of the three Patents. Briefly, that in one “preferred embodiment” each of the patents described that the mobile security system may be incorporated within the mobile device. Thus, the CAFC concluded that “highly persuasive” evidence would be required to read claims as excluding a preferred embodiment of the invention. Vitronics Corp. v. Conceptronic, Inc., 90 F.3d 1576, 1583–84 (Fed. Cir. 1996). Indeed, “a claim interpretation that excludes a preferred embodiment from the scope of the claim is rarely, if ever, correct.” Accent Pack-aging, Inc. v. Leggett & Platt, Inc., 707 F.3d 1318, 1326 (Fed. Cir. 2013) (citation omitted).

CUPP responds that, because at least one independent claim in each of the patents requires the security system to send a signal “to” the mobile device, and “communicate with” the mobile device, the system must be remote from the mobile device processor.

The CAFC were not persuaded holding that the Board properly construed the security system processor limitation in line with the specification. The CAFC analogized that “just as a person can send an email to him- or herself, a unit of a mobile device can send a signal “to,” or “communicate with,” the device of which it is a part.”

Next, CUPP argued that, because it disclaimed a non-remote security system processor during the initial examination of one of the patents at issue, the Board’s construction is erroneous. The CAFC held that the Board properly rejected that argument, because CUPP’s disclaimer did not unmistakably renounce security system processors embedded in a mobile device. Rather, the CAFC upheld the Board’s reading of CUPP’s remarks during prosecution as a “reasonable interpretation[]” that defeats CUPP’s assertion of prosecutorial disclaimer. Avid Tech., Inc., 812 F.3d at 1045 (citation omitted); see also J.A. 20–22.

Briefly, during prosecution of the ’683 patent, the Patent Office examiner found all claims in the application obvious in light of the prior art. CUPP’s responded that if the TPM “were implemented as a stand-alone chip attached to a PC mother-board,” it would be “part of the motherboard of the mobile devices” rather than being a separate processor. J.A. 3578. The TPM would therefore not constitute “a mobile security system processor different from a mobile system processor.”

The Board found, and the CAFC upheld, that under one plausible reading, CUPP’s point was that the prior art failed to teach different processors because the TPM lacks a distinct processor. Thus, under this interpretation, if the TPM were “a stand-alone chip attached to a . . . motherboard,” it would rely on the motherboard’s processor, and not have its own different processor. For this reason, the CAFC concluded that CUPP’s comment to the examiner is consistent with it retaining claims to security system processors embedded in a mobile device with a separate processor.

Lastly, CUPP contended that the Board erred by rejecting CUPP’s disclaimer in the IPRs themselves, disavowing a security system processor embedded in a mobile device.

Here, the CAFC unambiguously stated that it was making “precedential the straightforward conclusion [they] drew in an earlier nonprecedential opinion: “[T]he Board is not required to accept a patent owner’s arguments as disclaimer when deciding the merits of those arguments.” VirnetX Inc. v. Mangrove Partners Master Fund, Ltd., 778 F. App’x 897, 910 (Fed. Cir. 2019). That a rule permitting a patentee to tailor its claims in an IPR through argument alone would substantially undermine the IPR process. Congress designed inter partes review to “giv[e] the Patent Office significant power to revisit and revise earlier patent grants,” thus “protect[ing] the public’s paramount interest in seeing that patent monopolies are kept within their legitimate scope.” If patentees could shapeshift their claims through argument in an IPR, they would frustrate the Patent Office’s power to “revisit” the claims it granted, and require focus on claims the patentee now wishes it had secured. See also Oil States Energy Servs., LLC v. Greene’s Energy Grp., LLC, 138 S. Ct. 1365, 1373 (2018).

Thus, to conclude, a disclaimer in an IPR proceeding is only binding in later proceedings, whether before the PTO or in court. The CAFC emphasized that congress created a specialized process for patentees to amend their claims in an IPR, and CUPP’s proposed rule would render that process unnecessary because the same outcome could be achieved by disclaimer. See 35 U.S.C. § 316(d).

Take-away:

- A disclaimer in an IPR proceeding is only binding in later proceedings, whether before the PTO or in court.

- A claim interpretation that excludes a preferred embodiment from the scope of the claim is rarely, if ever, correct.

- Disclaimers made during prosecution must be clear and unmistakable to be relied upon later. Specifically: “The doctrine of prosecution disclaimer precludes patentees from recapturing through claim interpretation specific meanings disclaimed during prosecution.” Mass. Inst. of Tech. v. Shire Pharms., Inc., 839 F.3d 1111, 1119 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (ellipsis, alterations, and citation omitted). However, a patentee will only be bound to a “disavowal [that was] both clear and unmistakable.” Id. (citation omitted). Thus, where “the alleged disavowal is ambiguous, or even amenable to multiple reasonable interpretations, we have declined to find prosecution disclaimer.” Avid Tech., Inc. v. Harmonic, Inc., 812 F.3d 1040, 1045 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

- Claim terms are given their ordinary meaning unless persuasive reason is provided to apply a more specialized meaning to the word.

MERE AUTOMATION OF MANUAL PROCESSES USING GENERIC COMPUTERS DOES NOT CONSTITUTE A PATENTABLE IMPROVEMENT IN COMPUTER TECHNOLOGY

Sung-Hoon Kim | December 6, 2022

International Business Machines Corporation v. Zillow Group, Inc., Zillow, Inc.

Decided: October 17, 2022

Hughes (author), Reyna, and Stoll (dissenting in parts)

Summary:

In 2019, IBM sued Zillow for infringement of several patents related to graphical display technology in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington. Zillow filed a motion for judgment on the pleadings, arguing that the claims of IBM’s asserted patents were patent ineligible under § 101. The district court granted Zillow’s motion as to two IBM patents because they were directed to abstract ideas with no inventive concept. The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court decision and therefore, affirmed.

Details:

Two asserted IBM patents are U.S. Patent Nos. 9,158,789 (“the ’789 patent”) and 7,187,389 (“the ’389 patent”).

The ’789 patent

This patent describes a method for “coordinated geospatial, list-based and filter-based selection.” Here, a user draws a shape on a map to select that area of the map, and the claimed system then filters and displays data limited to that area of the map.

Claim 8 is a representative claim:

A method for coordinated geospatial and list-based mapping, the operations comprising:

presenting a map display on a display device, wherein the map display comprises elements within a viewing area of the map display, wherein the elements comprise geospatial characteristics, wherein the elements comprise selected and unselected elements;

presenting a list display on the display device, wherein the list display comprises a customizable list comprising the elements from the map display;

receiving a user input drawing a selection area in the viewing area of the map display, wherein the selection area is a user determined shape, wherein the selection area is smaller than the viewing area of the map display, wherein the viewing area comprises elements that are visible within the map display and are outside the selection area;

selecting any unselected elements within the selection area in response to the user input drawing the selection area and deselecting any selected elements outside the selection area in response to the user input drawing the selection area; and

synchronizing the map display and the list display to concurrently update the selection and deselection of the elements according to the user input, the selection and deselection occurring on both the map display and the list display.

The ’389 patent

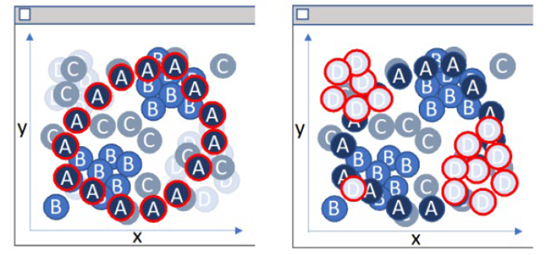

This patent describes methods of displaying layered data on a spatially oriented display based on nonspatial display attributes (i.e., displaying objects in visually distinct layers). Here, objects in layers of interest could be emphasized while other layers could be deemphasized.

Claim 1 is a representative claim:

A method of displaying layered data, said method comprising:

selecting one or more objects to be displayed in a plurality of layers;

identifying a plurality of non-spatially distinguishable display attributes, wherein one or more of the non-spatially distinguishable display attributes corresponds to each of the layers;

matching each of the objects to one of the layers;

applying the non-spatially distinguishable display attributes corresponding to the layer for each of the matched objects;

determining a layer order for the plurality of layers, wherein the layer order determines a display emphasis corresponding to the objects from the plurality of objects in the corresponding layers; and

displaying the objects with the applied non-spatially distinguishable display attributes based upon the determination, wherein the objects in a first layer from the plurality of layers are visually distinguished from the objects in the other plurality of layers based upon the non-spatially distinguishable display attributes of the first layer.

Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit reviewed the grant of a Rule 12 motion under the law of the regional circuit (de novo for the Ninth Circuit).

As for Alice step one analysis of the ’789 patent, the Federal Circuit held that the claims fail to recite any inventive technology for improving computers as tools, and instead directed to “an abstract idea for which computers are invoked merely as a tool.”

The Federal Circuit further held that identifying, analyzing, and presenting any data to a user is not an improvement specific to computer technology, and that mere automation of manual processes using generic computers is not a patentable improvement in computer technology.

The Federal Circuit held that this patent describes functions (presenting, receiving, selecting, synchronizing) without explaining how to accomplish these functions.

As for Alice step two analysis of the ’789 patent, the Federal Circuit noted that IBM has not made any allegations that any features of the claims is inventive. Instead, the Federal Circuit held that the limitations in this patent simply describe the abstract method without providing more.

As for Alice step one analysis of the ’389 patent, the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that this patent is directed to the abstract idea of organizing and displaying visual information (merely organize and arrange sets of visual information into layers and present the layers on a generic display device).

The Federal Circuit held that like the ’789 patent, this patent describes various functions without explaining how to accomplish any of them.

The Federal Circuit further held that the problem this patent tries to solve is not even specific to a computing environment, and the solution that this patent provides could be accomplished using colored pencils and translucent paper.

As for Alice step two analysis of the ’389 patent, the Federal Circuit noted that dynamic re-layering or rematching could also be done by hand (slowly), and that any of the patent’s improved efficiency does not come from an improvement in the computer but from applying the claimed abstract idea to a computer display.

Therefore, the Federal Circuit held that there is no inventive concept that transforms the abstract idea of organizing and displaying visual information into a patent-eligible application of that abstract idea.

Dissent by Stoll

Judge Stoll agreed with the majority opinion. However, she did not agree with the majority opinion that claims 9 and 13 of the ’389 patent are not patent eligible.

The information handling system as described in claim 8 further comprising:

a rearranging request received from a user;

rearranging logic to rearrange the displayed layers, the rearranging logic including:

re-matching logic to re-match one or more objects to a different layer from the plurality of layers;

application logic to apply the non-spatially distinguishable display attributes corresponding to the different layer to the one or more re-matched objects; and

display logic to display the one or more rematched objects.

She noted that in combination with factual allegations in the complaint (problems with the conventional technology with larger and complex data systems) and the expert declaration, the claimed relaying and rematching steps are directed to a technical improvement in how a user interacts with a computer with the GUI.

Takeaway:

- The argument that the claimed invention improves a user’s experience while using a generic computer is not sufficient to render the claims patent eligible at Alice step one analysis.

- Identifying, analyzing, and presenting certain data to a user is not an improvement specific to computing technology itself (mere automation of manual processes using generic computers not sufficient).

- The specification should be drafted to explain how to accomplish the required functions instead of merely describing them (avoid “result-based functional language”).

Tags: 35 U.S.C. §101 > Alice > patent eligible subject matter > patent ineligible subject matter

Throwing in Kitchen Sink on 101 Legal Arguments Didn’t Help Save Patent from Alice Ax

John Kong | November 21, 2022

In Re Killian

Taranto, Clevenger, Chen (August 23, 2022).

Summary:

Killian’s claim to “determining eligibility for Social Security Disability Insurance [SSDI] benefits through a computer network” was deemed “clearly patent ineligible in view of our precedent.” However, the Federal Circuit also disposes of a host of the appellant’s legal challenges to 101 jurisprudence, including:

(A) all court and Board decisions finding a claim patent ineligible under Alice/Mayo is arbitrary and capricious under the APA;

(B) comparing this case to other cases in which this court and the Supreme Court considered issues of patent eligibility under 101 violates the appellant’s due process rights because Mr. Killian had no opportunity to appear in those other cases;

(C) the search for an “inventive concept” at Alice Step 2 is improper because Congress did away with an “invention” requirement when it enacted the Patent Act of 1952;

(D) “mental steps” ineligibility has no foundation in modern patent law; and

(E) there is no substantial evidence to support the rejections in view of the PTAB’s “evidentiary vacuum” in assessing the factual inquiry into whether the claimed process is well-understood, routine, and conventional.

Procedural History:

The PTAB’s affirmance of the examiner’s final rejection of Killian’s US Patent Application No. 14/450,024 under 35 USC §101 was appealed to the Federal Circuit and was upheld.

Decision:

Representative claim 1 is as follows:

A computerized method for determining eligibility for social security disability insurance (SSDI) benefits through a computer network, comprising the steps of:

(a) providing a computer processing means and a computer readable media;

(b) providing access to a Federal Social Security database through the computer network, wherein the Federal Social Security database provides records containing information relating to a person’s status of SSDI and/or parental and/or marital information relating to SSDI benefit eligibility;

(c) selecting at least one person who is identified as receiving treatment for developmental disabilities and/or mental illness;

(d) creating an electronic data record comprising information relating to at least the identity of the person and social security number, wherein the electronic data record is recorded on the computer readable media;

(e) retrieving the person’s Federal Social Security record containing information relating to the person’s status of SSDI benefits;

(f) determining whether the person is receiving SSDI benefits based on the SSDI status information contained within the Federal Social Security database record through the computer network; and

(g) indicating in the electronic data record whether the person is receiving SSDI benefits or is not receiving SSDI benefits.

The court agreed with the PTAB that the thrust of this claim is “the collection of information from various sources (a Federal database, a State database, and a caseworker) and understanding the meaning of that information (determining whether a person is receiving SSDI benefits and determining whether they are eligible for benefits under the law).” Collecting information and “determining” whether benefits are eligible are mental tasks humans routinely do. That these steps are performed on a generic computer or “through a computer network” does not save these claims from being directed to an abstract idea under Alice step 1. Under Alice step 2, this is merely reciting an abstract idea and adding “apply it with a computer.” The claims do not recite any technological improvement in how a computer goes about “determining” eligibility for benefits. Merely comparing information against eligibility requirements is what humans seeking benefits would do with or without a computer.

The court also addresses appellant’s further challenges (A)-(E) as follows.

- all court and Board decisions finding a claim patent ineligible under Alice/Mayo is arbitrary and capricious under the APA

The standards of review in the APA do not apply to decisions by courts. The APA governs judicial review of “agency action.”

There was also an assertion that there is a Fifth Amendment Due Process Clause violation stemming from the imprecision of the Alice/Mayo standard. However, the court noted that Killian never argued that the Alice/Mayo standard runs afoul of the “void-for-vagueness doctrine” and could not have argued this because this case was not even a close call (vagueness as applied to the particular case is a prerequisite to establishing facial vagueness).

As for Board decisions finding patents ineligible as being arbitrary and capricious under the APA, “we may not announce that the Board acts arbitrarily and capriciously merely by applying binding judicial precedent.” This would be akin to using the APA to attack the Supreme Court’s interpretations of 101. However, “the APA does not empower us to review decisions of ‘the courts of the United States’ because they are not agencies.”

Mr. Killian also requested “a single non-capricious definition or limiting principle” for “abstract idea” and “inventive concept.” However, the court points out that there is “no single, hard-and-fast rule that automatically outputs an answer in all contexts” because there are different types of abstract ideas (mental processes, methods of organizing human activity, claims to results rather than a means of achieving the claimed result). Nevertheless, guidance has been provided (citing several cases).

And even if the Alice/Mayo framework is unclear, “both this court and the Board would still be bound to follow the Supreme Court’s §101 jurisprudence as best we can as we must follow the Supreme Court’s precedent unless and until it is overruled by the Supreme Court.”

- comparing this case to other cases in which this court and the Supreme Court considered issues of patent eligibility under 101 violates the appellant’s due process rights because Mr. Killian had no opportunity to appear in those other cases

Examination of and comparison to earlier caselaw is just classic common law methodology for deciding cases arising under 101. “Nothing stops Mr. Killian from identifying any important distinctions between his claimed invention and claims we have analyzed in prior cases.”

- the search for an “inventive concept” at Alice Step 2 is improper because Congress did away with an “invention” requirement when it enacted the Patent Act of 1952

First, Killian has not established that Alice Step 2’s “inventive concept” is the same thing as the “invention” requirement in the Patent Act of 1952. It is not. For instance, there is no requirement to ascertain the “degree of skill and ingenuity” possessed by one of ordinary skill in the art under Alice Step 2. In any event, the Supreme Court required the “inventive concept” inquiry at Step 2, and so, “search for an inventive concept we must.”

- “mental steps” ineligibility has no foundation in modern patent law

“This argument is plainly incorrect” (citing Benson, Mayo, Diehr, Bilski, etc.). “[W]e are bound by our precedential decisions holding that steps capable of performance in the human mind are, without more, patent-ineligible abstract ideas.”

- there is no substantial evidence to support the rejections in view of the PTAB’s “evidentiary vacuum” in assessing the factual inquiry into whether the claimed process is well-understood, routine, and conventional

Substantial evidence supported the PTAB’s decision regarding Alice Step 2. The additional elements of a computer processor and a computer readable media are generic, as the application itself admits (the PTAB cited to the specification’s description about how the claimed method “may be performed by any suitable computer system”). And, the claimed “creating an electronic data record,” “indicating in the electronic data record whether the person is receiving SSDI adult child benefits,” “providing a caseworker display system,” “generating a data collection input screen,” “indicating in the electronic data record whether the person is eligible for SSDI adult child benefits,” and other data tasks are merely selection and manipulation of information – are not a transformative inventive concept.

Mr. Killian also refers to 55 documents allegedly presented to the examiner and the PTAB. But, because these were not included in the joint appendix and nothing is explained on appeal as to what these 55 documents show, “Mr. Killian forfeited any argument on appeal based on those fifty-five documents by failing to present anything more than a conclusory, skeletal argument.”

Takeaways:

Given the continued dissatisfaction over the court’s eligibility guidance and the frustration over the Supreme Court’s refusal to take on §101 since Alice, this decision offers a rare insight into the court’s position on various §101 legal challenges. For instance, this decision appears to suggest a potential Fifth Amendment Due Process Clause violation stemming from the imprecision of the Alice/Mayo standard, but only for a “close call” case where vagueness can be established for the particular case, in order to challenge the facial vagueness of the Alice/Mayo standard under the “void-for-vagueness doctrine.”

The Testimony of an Expert Without the Requisite Experience Would Be Discounted in the Obviousness Determination

Bo Xiao | October 21, 2022

Best Medical International, Inc., v. Elekta Inc.

Before HUGHES, LINN, and STOLL, Circuit Judges. STOLL, Circuit Judge.

Summary

The Federal Circuit affirmed the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s determination that challenged claims are unpatentable as obvious over the prior art.

Background

Best Medical International, Inc (BMI) owns the patent at issue, U.S. Patent No. 6,393,096 (‘096). Patent ‘096 is directed to a medical device and method for applying conformal radiation therapy to tumors using a pre-determined radiation dose. The device and the method are intended to improve radiation therapy by computing an optimal radiation beam arrangement that maximizes radiation of a tumor while minimizing radiation of healthy tissue. Claim 43 is listed below as representative of the claims:

43. A method of determining an optimized radiation beam arrangement for applying radiation to at least one tumor target volume while minimizing radiation to at least one structure volume in a patient, comprising the steps of:

distinguishing each of the at least one tumor target volume and each of the at least one structure volume by target or structure type;

determining desired partial volume data for each of the at least one target volume and structure volume associated with a desired dose prescription;

entering the desired partial volume data into a computer;

providing a user with a range of values to indicate the importance of objects to be irradiated;

providing the user with a range of conformality control factors; and

using the computer to computationally calculate an optimized radiation beam arrangement.

Varian Medical Systems, Inc. filed two IPR petitions challenging some claims of the ’096 patent. Soon after the Board instituted both IPRs, Elekta Inc. filed petitions to join Varian’s instituted IPR proceedings. The Board issued the final written decisions that determined the challenged claims 1, 43, 44, and 46 were unpatentable as obvious.

Prior to the Board’s final decisions, BMI canceled claim 1 in an ex parte reexamination where the Examiner rejected claim 1 based on the finding of statutory and obviousness-type double patenting. Although BMI had canceled claim 1, the Board still considered the merits of Elekta’s patentability challenge for claim 1 and concluded that claim 1 was unpatentable in its final decision. The Board explained that claim 1 had not been canceled by final action as BMI had “not filed a statutory disclaimer.” BMI appealed the Board’s final written decisions. Varian later withdrew from the appeal.

Discussion

The Federal Circuit first addressed the threshold question of jurisdiction. BMI asked for a vacatur of the Board’s patentability determination by arguing “the Board lacked authority to consider claim 1’s patentability because that claim was canceled before the Board issued its final written decision, rendering the patentability question moot.” The Federal Circuit found that it was proper for the Board to address every challenged claim during the IPR under the Supreme Court’s decision in SAS Institute Inc. v. Iancu in which the Supreme Court held that the Board in its final written decision “must address every claim the petitioner has challenged.” 138 S. Ct. 1348, 1354 (2018) (citing 35 U.S.C. § 318(a)). Furthermore, the Federal Circuit supported Elekta’s argument that BMI lacked standing to appeal the Board’s unpatentability determination. The Federal Circuit explained that BMI admitted during oral argument that claim 1 was canceled prior to filing its notice of appeal without challenging the rejections. Thus, the Federal Circuit found that there was no longer a case or controversy regarding claim 1’s patentability at that time. Accordingly, the Federal Circuit dismissed BMI’s appeal regarding claim 1 for lack of standing.

The Federal Circuit later moved to consider BMI’s challenges to the Board’s findings regarding the level of skill in the art, motivation to combine, and reasonable expectation of success. The Board’s finding put a requirement on the level of skill in the art that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have had “formal computer programming experience, i.e., designing and writing underlying computer code.” BMI’s expert did not have such requisite computer programming experience. Thus, BMI’s expert testimony was discounted in the Board’s obviousness analysis.

The Federal Circuit stated that there is a non-exhaustive list of factors in finding the appropriate level of skill in the art, these factoring including: “(1) the educational level of the inventor; (2) type of problems encountered in the art; (3) prior art solutions to those

problems; (4) rapidity with which innovations are made; (5) sophistication of the technology; and (6) educational level of active workers in the field.” The Federal Circuit found that both parties did not provide sufficient evidence relating to these factors. Elekta principally relied on its expert Dr. Kenneth Gall’s declaration, whereas BMI relied on Mr. Chase’s declaration. In Dr. Gall opinion, a person of ordinary skill in the art would have had “two or more years of experience in . . . computer programming associated with treatment plan optimization.” Mr. Chase only disagreed with “the requirement,” but did not provide any explanation as to why “the requirement of ‘two or more years of . . . computer programming associated with treatment plan optimization’” was “inappropriate.”

Despite competing expert testimony on a person of ordinary skill, the Federal Circuit took the Board’s side and held that the Board relied on “the entire trial record,” including the patent’s teachings as a whole, to conclude the level of skill in the art. The Federal Circuit cited several sentences from the specification of the ‘096 patent to explain why the Board was reasonable to conclude that a skilled artisan would have had formal computer programming experience. For example, representative claim 43 was cited, which recites “using the computer to computationally calculate an optimized radiation beam arrangement.” The written description in ‘096 patent also recites “optimization method may be carried out using . . . a conventional computer or set of computers, and plan optimization software, which utilizes the optimization method of the present invention.”

The Federal Circuit found that BMI’s additional arguments were unpersuasive. BMI argued that the claims require that one specific step must be accomplished using a single computer and the claimed “conformality control factors” are “mathematically defined parameter[s].” The Federal Circuit concluded that there is no error in the Board’s determination based on the plain claim language and written description. BMI also argued that the Board’s finding that the prior teaches “providing a user with a range of values to indicate the importance of objects to be irradiated” is unsupported by substantial evidence. The Federal Circuit was not persuaded, because Dr. Gall’s testimony provide the support that a skilled artisan would have found the feature obvious.

BMI also challenged the Board’s findings as to whether there would have been a motivation to combine the prior art of Carol-1995 with Viggars and whether a skilled artisan would have had a reasonable expectation of success. But the Federal Circuit found that the Board relied on the teachings of the references themselves to support both findings. Thus, it was concluded that the Board’s well-reasoned analysis was supported by substantial evidence.

Takeaway

- The level of skill in the art could be defined in the specification for determining obviousness.

- The testimony of an expert without the requisite experience would be discounted in the obviousness arguments.