File your patent application before attending a trade show to showcase your products

Sung-Hoon Kim | May 26, 2023

Minerva Surgical, Inc. v. Hologic, Inc., Cytyc Surgical Products, LLC

Decided: February 15, 2023

Summary:

Minerva Surgical, Inc. sued Hologic, Inc. and Cytyc Surgical Products, LLC in the District of Delaware for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 9,186,208 (“the ’208 patent”). Hologic moved for summary judgment of invalidity, arguing that the ’208 patent claims were anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b). The district court granted summary judgment that the asserted claims are anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) because the patented technology was “in public use,” and the technology was “ready for patenting.” The Federal Circuit held that the district court correctly determined that Minerva’s disclosure of their constituted the invention being “in public use,” and that the device was “ready for patenting.” Therefore, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s grant of summary judgment.

Details:

Minerva Surgical, Inc. sued Hologic, Inc. and Cytyc Surgical Products, LLC in the District of Delaware for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 9,186,208 (“the ’208 patent”).

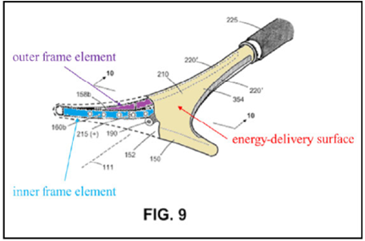

The ’208 patent is directed to surgical devices for a procedure called “endometrial ablation” for stopping or reducing abnormal uterine bleeding. This procedure includes inserting a device having an energy-delivery surface into a patient’s uterus, expanding the surface, energizing the surface to “ablate” or destroy the endometrial lining of the patient’s uterus, and removing the surface.

The application for the’208 patent was filed on November 2, 2021 and claims a priority date of November 7, 2011. Therefore, the critical date for the ’208 patent is November 7, 2010.

The ’208 patent

Independent claim 13 is a representative claim:

A system for endometrial ablation comprising:

an elongated shaft with a working end having an axis and comprising a compliant energy-delivery surface actuatable by an interior expandable-contractable frame;

the surface expandable to a selected planar triangular shape configured for deployment to engage the walls of a patient’s uterine cavity;

wherein the frame has flexible outer elements in lateral contact with the compliant surface and flexible inner elements not in said lateral contact, wherein the inner and outer elements have substantially dissimilar material properties.

The appeal focused on the claim term, “the inner and outer elements have substantially dissimilar material properties” (“SDMP” term”).

District Court

After discovery, Hologic moved for summary judgment of invalidity, arguing that the ’208 patent claims were anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b).

The district court granted summary judgment that the asserted claims are anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) because of the following reasons:

First, the patented technology was “in public use” because Minerva disclosed fifteen devices (“Aurora”) at an event, where Minerva showcased them at a booth, in meeting with interested parties, and in a technical presentation. Also, Minerva did not disclose them under any confidentiality obligations.

Second, the technology was “ready for patenting” because Minerva created working prototypes and enabling technical documents.

Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit reviewed a district court’s grant of summary judgment under the law of the regional circuit (Third Circuit).

The Federal Circuit held that “the public use bar is triggered ‘where, before the critical date, the invention is [(1)] in public use and [(2)] ready for patenting.’”

The “in public use” element is satisfied if the invention “was accessible to the public or was commercially exploited” by the invention.

“Ready for patenting” requirement can be shown in two ways – “by proof of reduction to practice before the critical date” and “by proof that prior to the critical date the inventor had prepared drawings or other descriptions of the invention that were sufficiently specific to enable a person skilled in the art to practice the invention.”

The Federal Circuit held that disclosing the Aurora device at the event (American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (“AAGL 2009”)) constituted the invention being “in public use” because this event included attendees who were critical to Minerva’s business, and Minerva’s disclosure of their devices included showcasing them at a booth, in meeting with interested parties, and in a technical presentation.

The Federal Circuit noted that AAGL 2009 was the “Super Bowl” of the industry and was open to the public, and that Minerva had incentives to showcase their products to the attendees. Also, Minerva sponsored a presentation by one of their board members to highlight their products and pitched their products to industry members, who were able to see how they operate.

The Federal Circuit also noted that there were no “confidentiality obligations imposed upon” those who observed Minerva’s devices, and that the attendees were not required to sign non-disclosure agreements.

The Federal Circuit also held that Minerva’s Aurora devices at the event disclosed the SDMP term because Minerva’s documentation about this device from before and shortly after the event disclosed this device having the SDMP terms or praises benefits derived from this device having the SDMP technology.

The Federal Circuit held that the record clearly showed that Minerva reduced the invention to practice by creating working prototypes that embodied the claim and worked for the intended purpose.

The Federal Circuit noted that there was documentation “sufficiently specific to enable a person skilled in the art to practice the invention” of the disputed SDMP term. Here, the documentation included the drawings and detailed descriptions in the lab notebook pages disclosing a device with the SDMP term.

Therefore, the Federal Circuit held that the district court correctly determined that Minerva’s disclosure of the Aurora device constituted the invention being “in public use” and that the device was “ready for patenting.”

Accordingly, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s grant of summary judgment because there are no genuine factual disputes, and Hologic is entitled to judgment as a matter of law that the ’208 patent is anticipated under the public use bar of § 102(b).

Takeaway:

- File your patent application before attending a trade show to showcase your products.

- Have the attendees of the trade show sign non-disclosure agreements, if necessary.

Tags: 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) > confidentiality > critical date > enablement > pre-AIA > prototype > public use > reduction to practice > summary judgment

Common Sense Still Applies In Claim Construction

John Kong | May 13, 2023

Alterwan, Inc. v Amazon.com Inc

Decided: March 13, 2023

Before Lourie, Dyk, Stoll (Opinion by Dyk)

Summary:

For a claim term “non-blocking bandwidth,” the district court accepted the applicant-as-his-own-lexicographer definition set forth in the specification to mean “a bandwidth that will always be available and will always be sufficient.” This meant that bandwidth must be available even when the Internet is down – which is impossible (and hence, the parties’ agreed-upon stipulation of non-infringement with this claim interpretation). Courts will not rewrite “unambiguous” claim language to cure such absurd positions or to sustain validity. But, when the claim language is “not unambiguous” concerning the disputed interpretation, common sense applies in claim construction, especially in view of the proper context for the source of the applicant-as-his-own-lexicographer definition.

Procedural History:

Alterwan sued Amazon for patent infringement. After a Markman hearing and motions for summary judgment by both parties, the district court changed the claim construction for “cooperating service provider” at a summary judgment hearing to be a “service provider that agrees to provide non-blocking bandwidth.” The district court construed “non-blocking bandwidth” to be “a bandwidth that will always be available and will always be sufficient” which meant that the bandwidth will be available even if the Internet is down. With this updated construction, the parties filed a stipulation and order of non-infringement of the patents-in-suit. Amazon argued, and the patentee agreed, that if the claim required bandwidth provision even when the Internet is down, Amazon could not possibly infringe. The district court entered the stipulated judgment of non-infringement and the parties appealed.

Decision:

Representative claim 1 is as follows:

An apparatus, comprising:

an interface to receive packets;

circuitry to identify those packets of the received packets corresponding to a set of one or more predetermined addresses, to identify a set of one or more transmission paths associated with the set of one or more predetermined addresses, and to select a specific transmission path from the set of one or more transmission paths; and

an interface to transmit the packets corresponding to the set of one or more predetermined addresses using the specific transmission path;

wherein

each transmission path of the set of one or more transmission paths is associated with a reserved, non-blocking bandwidth, and

the circuitry is to select the specific transmission path to be a transmission path from the [sic] set of one or more transmission paths that corresponds to a minimum link cost relative to each other transmission path in the set of one or more transmission paths.

The specification states “the quality of service problem that has plagued prior attempts is solved by providing non-blocking bandwidth (bandwidth that will always be available and will always be sufficient)…” (USP 8,595,478, col. 4, line 66 to col. 5, line 2). Accordingly, “non-blocking bandwidth” was defined by the applicant, acting as his own lexicographer, to mean “a bandwidth that will always be available and will always be sufficient.”

Normally, “[c]ourts may not redraft claims, whether to make them operable or to sustain validity” (citing, Chef Am., Inc. v. Lamb-Weston, Inc., 358 F.3d 1371, 1374 (Fed. Cir. 2004)). In Chef America, the claim limitation “heating the resulting batter-coated dough to a temperature in the range of about 400°F to 850°F” would lead to an absurd result in that the dough would be burnt. Instead, the limitation would be made operable if it recited heating the dough “at” a temperature in the range of about 400°F to 850°F. However, since the limitation at issue was unambiguous, the court declined to rewrite the claim to replace the term “to” with “at.”

However, the court noted that, “[h]ere, the claim language itself does not unambiguously require bandwidth to be available even when the Internet is inoperable.” So, “Chef America does not require us to depart from common sense in claim construction.” Without “unambiguous” claim language requiring the disputed interpretation (“a bandwidth that will always be available and will always be sufficient”), the court proceeded to check the context for the support for the disputed interpretation. That “context” included specification discussion of wide area network technology that uses the internet as a backbone, and several “quality of service” problems that arise from the use of the internet as a backbone, including latency problems in the delays for critical transmission packets getting from a source to a destination over that internet backbone. The patent’s solution was to provide “preplanned high bandwidth, low hop-count routing paths” between sites that are geographically separated. These preplanned routing paths are a “key characteristic that all species within the genus of the invention will share.” It is after this discussion that the specification then concludes “[i]n other words, the quality of service problem that has plagued prior attempts is solved by providing non-blocking bandwidth (bandwidth that will always be available and will always be sufficient) and predefining routes for the ’private tunnel’ paths between points on the internet…”

Providing bandwidth even with the Internet being down is an impossibility. The specification describes operability and transmission over the Internet as a backbone and is completely silent about provision of bandwidth when the Internet is unavailable. In context, the definitional sentence for “non-blocking bandwidth” is addressing the problem of latency (when the Internet is operational), rather than providing for bandwidth even when there is no Internet. The court’s decision does not opine on what the meaning of non-blocking bandwidth is, but holds that “it does not require bandwidth when the Internet is down.”

Takeaways:

The court will not redraft claim language during claim construction to maintain operability or sustain validity when the claim language is unambiguous. But, when the claim language is “not unambiguous,” common sense applies, especially when looking at any source of the disputed interpretation in context.

What’s the Problem? CAFC reverses PTAB for identifying the problem to be solved in finding combined references analogous when the burden was properly on the Petitioner

Michael Caridi | May 11, 2023

Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GMBH v. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Decided: May 9, 2023

Before Reyna, Mayer and Cunningham. Opinion by Cunningham.

Summary:

The Court reverses a PTAB final written decision finding all challenged claims of Safoni’s patent unpatentable as obvious over prior art. The Court held that Mylan improperly argued a first prior art reference is analogous to another prior art reference and not the challenged patent. Therefore Mylan failed to meet its burden to establish obviousness premised on the first reference since the Board’s factual finding that the first reference is analogous to the patent-in-suit is unsupported by substantial evidence.

Background:

Mylan filed an IPR against Sanofi’s RE47,614 (“the ‘614 patent”) alleging its unpatentability in light of a combination of three prior art references: (1) U.S. Patent Application No. 2007/0021718 (“Burren”); (2) U.S. Patent No. 2,882,901 (“Venezia”); and (3) U.S. Patent No. 4,144,957 (“de Gennes”). Claim 1 of the ‘614 patent is directed to a drug delivery device with a spring washer arranged within a housing so as to exert a force on a drug carrying cartridge and to secure the cartridge against movement with respect to a cartridge retaining member, the spring washer has at least two fixing elements configured to axially and rotationally fix the spring washer relative to the housing.

Mylan asserted that Burren with Venezia taught the use of spring washers within drug-delivery devices and relied on de Gennes to add “snap-fit engagement grips” to secure the spring washer. Burren and Venezia were both within the field of a drug delivery system. However, de Gennes was non-analogous art being directed to a clutch bearing in the automotive field. Sanofi argued that the combination was improper because de Gennes was non-analogous art. Mylan responded that de Gennes was analogous in that it was relevant to the pertinent problem in the drug delivery art and cited to Burren as providing a problem which a skilled artisan may look to extraneous art to solve.

The PTAB found that Burren in combination with Venezia and de Gennes does render the challenged claims unpatentable relying on the “snap-fit connection” of de Gennes as equivalent to the “fixing elements” of the ’614 patent. Sanofi appealed.

Discussion:

In its appeal, Sanofi argued that the PTAB “altered and extended Mylan’s deficient showing” by analyzing whether de Gennes constitutes analogous art to the ’614 patent when Mylan, the petitioner, only presented its arguments with respect to Burren (i.e. other prior art). Mylan countered that the Board had found de Gennes as analogous art because there was “no functional difference between the problem of Burren and the problem of the ‘614 patent.”

In its review of the law governing whether prior art is analogous, the CAFC noted that “we have consistently held that a patent challenger must compare the reference to the challenged patent” and, citing precedent, noted that the proper test is whether prior art is “reasonably pertinent to the particular problem with which the inventor is involved.” The CAFC expanded thereon stating:

Mylan’s arguments would allow a challenger to focus on the problems of alleged prior art references while ignoring the problems of the challenged patent. Even if a reference is analogous to one problem considered in another reference, it does not necessarily follow that the reference would be analogous to the problems of the challenged patent…[broad construction of analogous art]… does not allow a fact finder to focus on the problems contained in other prior art references to the exclusion of the problem of the challenged patent.

The Court re-emphasized that the petitioner has the burden of proving unpatentability and that they have reversed the Board’s patentability determination where a petitioner did not adequately present a motivation to combine.

Conclusion:

The CAFC concluded that the Board’s decision did not interpret Mylan’s obviousness argument as asserting de Gennes was analogous to the ’614 patent, but rather improperly relied on de Gennes being analogous to the primary reference, Burren. As such, Mylan did not meet its burden to establish obviousness premised on de Gennes; and therefore, the Board’s factual finding that de Gennes is analogous to the ’614 patent is unsupported by substantial evidence. The Court reversed the finding of obviousness.

Take away:

- Relying on non-analogous art to support an obviousness contention requires looking at the problems the inventor of the patent-in-issue would find pertinent not those set forth in other relied upon prior art. Arguments that a problem solved by non-analogous art should focus on the inventor of the patent-in-issue as recognizing the problem to be solved not generally problems recognized in the art.

- Petitioner’s in IPRs should be cautious relying on the PTAB formulating an argument outside of those clearly set forth in their filings. Extrapolation of Petitioner’s arguments by the PTAB can open the possibility of a reversal based on lack of substantial evidence.

Limitations of Result-Based Functional Language and Generic Computer Components in Patent Eligibility

Bo Xiao | May 2, 2023

Hawk Technology Systems, Llc V. Castle Retail, LLC

Before REYNA, HUGHES, and CUNNINGHAM, Circuit Judges.

Summary

The district court granted Castle Retail’s motion, finding that the patent claims were directed towards the abstract idea of storing and displaying video without providing an inventive step to transform the abstract idea into a patent-eligible invention. The district court dismissed Hawk’s case, and Hawk appealed. The Federal Circuit upheld the district court’s decision, affirming that the patent claims were invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

Background

Hawk Technology Systems is the owner of a US Patent No. 10,499,091 ( the ’91 patent) entitled “High-Quality, Reduced Data Rate Streaming Video Product and Monitoring System.” The patent was filed in 2017 and granted in 2019, with priority claimed back to 2002. It describes a technique for displaying multiple stored video images on a remote viewing device in a video surveillance system, using a configuration that utilizes existing broadband infrastructure and a generic PC-based server to transmit signals from cameras as streaming sources at low data rates and variable frame rates. The patent claims that this approach reduces costs, minimizes memory storage requirements, and enhances bandwidth efficiency.

Hawk Technology Systems sued Castle Retail for patent infringement in Tennessee, alleging that Castle Retail’s use of security surveillance video operations in its grocery stores infringed on Hawk’s patent. Castle Retail moved to dismiss the case, arguing that the patent claims were invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 101, as they were directed towards ineligible subject matter.

The ‘091 patent contains six claims, but the appellant, Hawk Technology Systems, did not assert that there was any significant difference between the claims regarding eligibility. As a result, claim 1 was selected as representative, which recites:

1. A method of viewing, on a remote viewing device of a video surveillance system, multiple simultaneously displayed and stored video images, comprising the steps of:

receiving video images at a personal computer based system from a plurality of video sources, wherein each of the plurality of video sources comprises a camera of the video surveillance system;

digitizing any of the images not already in digital form using an analog-to-digital converter;

displaying one or more of the digitized images in separate windows on a personal computer based display device, using a first set of temporal and spatial parameters associated with each image in each window;

converting one or more of the video source images into a selected video format in a particular resolution, using a second set of temporal and spatial parameters associated with each image;

contemporaneously storing at least a subset of the converted images in a storage device in a network environment;

providing a communications link to allow an external viewing device to access the storage device;

receiving, from a remote viewing device remoted located remotely from the video surveillance system, a request to receive one or more specific streams of the video images;

transmitting, either directly from one or more of the plurality of video sources or from the storage device over the communication link to the remote viewing device, and in the selected video format in the particular resolution, the selected video format being a progressive video format which has a frame rate of less than substantially 24 frames per second using a third set of temporal and spatial parameters associated with each image, a version or versions of one or more of the video images to the remote viewing device, wherein the communication link traverses an external broadband connection between the remote computing device and the network environment; and

displaying only the one or more requested specific streams of the video images on the remote computing device.

In September 2021, the district court granted Castle Retail’s motion to dismiss the case. The court found that the claims in Hawk’s ‘091 patent failed the two-part Alice test. The court determined that the ‘091 patent is directed to an abstract idea of a method for storing and displaying video, and that the claimed elements are generic computer elements without any technological improvement.

Hawk’s argument that the temporal and spatial parameters are the inventive concept was also rejected, as the claims and specification failed to explain what those parameters are or how they should be manipulated. The district court also found that the claimed “analog-to-digital converter” and “personal computer based system” were not technological improvements, but rather generic computer elements. Additionally, it determined that the “parameters and frame rate” defined in the claims and specification did not appear to be more than manipulating data in a way that has been found to be abstract.

The district court concluded that the claims can be implemented using off-the-shelf, conventional computer technology and entered judgment against Hawk. Hawk appealed the decision.

Discussion

The Federal Circuit applied Alice step one in this case to determine if the ’091 patent claims were directed to an abstract idea. They agreed with the district court’s conclusion that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of “storing and displaying video.”

The Federal Circuit further clarified that the claims are directed to a method of receiving, displaying, converting, storing, and transmitting digital video “using result-based functional language.” Two-Way Media Ltd. v. Comcast Cable Commc’ns, LLC, 874 F.3d 1329, 1337 (Fed. Cir. 2017). The claims require various functional results of “receiving video images,” “digitizing any of the images not already in digital form,” “displaying one or more of the digitized images,” “converting one or more of the video source images into a selected video format,” “storing at least a subset of the converted images,” “providing a communications link,” “receiving . . . a request to receive one or more specific streams of the video images,” “transmitting . . . a version of one or more of the video images,” and “displaying only the one or more requested specific streams of the video images.”

Hawk argued that the ’091 patent claims were not directed to an abstract idea but to a specific technical problem and solution related to maintaining full-bandwidth resolution while providing professional quality editing and manipulation of digital video images. However, this argument failed because the Federal Circuit found that the claims themselves did not disclose how the alleged goal was achieved and that converting information from one format to another is an abstract idea. Furthermore, the claims did not recite a specific solution to make the alleged improvement concrete and, at most, recited abstract data manipulation. Therefore, the ’091 patent claims lacked sufficient recitation of how the purported invention improved the functionality of video surveillance systems and amounted to a mere implementation of an abstract idea.

At Alice step two, the claim elements were examined individually and as a combination to determine if they transformed the claim into a patent-eligible application of the abstract idea. The district court found that the claims did not show a technological improvement in video storage and display and that the limitations could be implemented using generic computer elements.

Hawk argued that the claims provided an inventive solution that achieved the benefit of transmitting the same digital image to different devices for different purposes while using the same bandwidth, citing specific tools, parameters, and frame rates. The Federal Circuit acknowledged that the claims mentioned “parameters.” However, the claims did not specify what these parameters were, and at most they pertained to abstract data manipulation such as image formatting and compression. Hawk did not contest that the claims involved conventional components to carry out the method. The Federal Circuit also noted that the ‘091 patent affirmed that the invention was meant to “utilize” existing broadband media and other conventional technologies. Thus, the Federal Circuit found that there is nothing inventive in the ordered combination of the claim limitations and noted that Hawk has not pointed to anything inventive.

The Federal Circuit determined that the claims in the ‘091 patent did not transform the abstract concept into something substantial and therefore did not pass the second step of the Alice test. As a result, the Federal Circuit concluded that the ‘091 patent is ineligible since its claims address an abstract idea that was not transformed into eligible subject matter.

Takeaway

- Reciting an abstract idea performed on a set of generic computer components does not contain an inventive concept.

- Claims that use result-based functional language in combination with generic computer components may not be sufficient to transform an abstract idea into patent-eligible subject matter.