Lying in a Deposition – Never a Good Policy

| June 2, 2021

Cap Export, LLC v. Zinus, Inc.

Decided on May 5, 2021

Summary

Rule 60(b)(3) relieves a patent challenger of a final judgment entered in favor of a patentee where the patent challenger with due diligence could not discover a later-revealed fraud committed by the patentee during the underlying litigation in which the deposed patentee’s witness lied to conceal his knowledge of on-sale prior art determined to be highly material to the validity of the patent.

Details

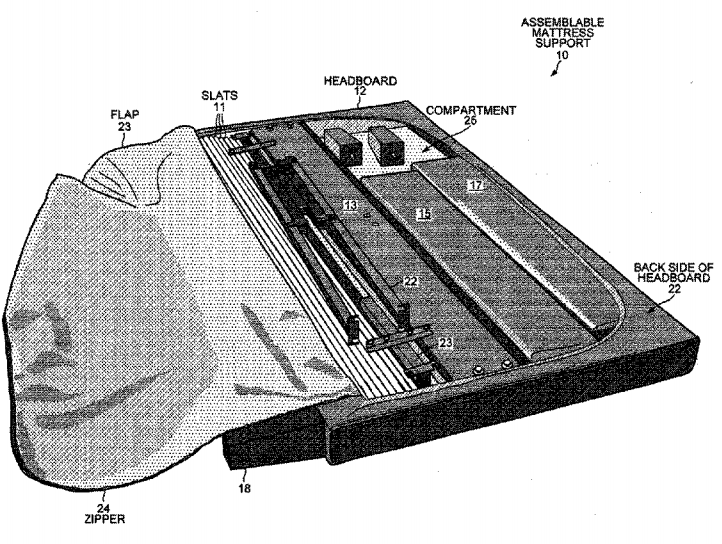

Zinus owns U.S. Patent No. 8,931,123 (“the ’123 patent”) entitled “Assemblable mattress support whose components fit inside the headboard.” The invention allows for packing various components of a bed into its headboard compartment for easy shipping in a compact state. The concept may be seen in one of the ‘123 patent figures:

The application that resulted in the ‘123 patent was filed in September 2013.

In 2016, Cap Export, LLC (“Cap Export”) sought declaratory judgment of invalidity and noninfringement of the ‘123 patent in the Central District of California. The lawsuit eventually resulted in the district court upholding the validity of the ‘123 patent claims as not anticipated or obvious over all prior art references considered. The final judgment stipulated and entered in favor of Zinus included payment of $1.1 million in damages to Zinus, and a permanent injunction against Cap Export[1]. Particularly relevant to the present case is the fact that in the course of the lawsuit, Cap Export deposed Colin Lawrie, Zinus’s president and expert witness, as to his knowledge of various prior art items.

In 2019, Zinus sued another company for infringement of the ‘123 patent. This second lawsuit prompted Cap Export to learn that Zinus’s group company had bought hundreds of beds manufactured by a foreign company which apparently had a bed-in-a-headboard feature, before the filing date of the ‘123 patent. Colin Lawrie, the aforementioned Zinus’s president, appears to be involved in this transaction as the purchase invoice was signed by Lawrie himself.

Cap Export then timely filed a Rule 60(b)(3) motion for relief from the final judgment, alleging that Lawrie during the previous deposition lied to Cap Export’s counsel. Some questions and answers highlighted in the case include:

Q. Prior to September 2013 had you ever seen a bed that was shipped disassembled in one box?

A. No.

Q. Not even—I’m not talking about everything stored in the headboard, I’m just saying one box.

A. No, I don’t think I have.

In the Rule 60(b)(3) proceeding, Lawrie admitted that his deposition testimony was “literally incorrect” while denying intentional falsity because he had misunderstood the question to refer to a bed contained “in one box with all of the components in the headboard,” rather than a bed contained “in one box” (where most laypersons should know of the latter, if not the former).

The district court was not convinced, pointing to the fact that Cap Export’s counsel had rephrased the question to distinguish the two concepts. Also, emails were discovered showing repeated sales of the beds at issue to Zinus’s family companies, the record which Zinus admitted had been in its possession throughout the underlying litigation.

The district court set aside the final judgement under Rule 60(b)(3), finding that the purchased beds were “functionally identical in design” to the ’123 patent claims, and that Lawrie’s repeated denials of his knowledge of such beds amounted to affirmative misrepresentations. Zinus appealed.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed.

FRCP Rule 60(b)(3)

Rule 60(b)(3) relieves a losing party of a final judgment where an opposing party commits “fraud … , misrepresentation, or misconduct.” The Ninth Circuit applies an additional requirement that the fraud not be discoverable through “due diligence”[2]. A movant must prove by clear and convincing evidence that the opposing party has obtained the verdict in its favor through fraudulent conduct which “prevented the losing party from fully and fairly presenting the defense.” Since the issue is procedural, the Federal Circuit follows regional circuit law and reviews the district court decision for abuse of discretion.

Due Diligence in Discovering Fraud

Zinus’s main contention was that the due diligence requirement is not satisfied, arguing that the key evidence would have been discovered had Cap Export’s counsel taken more rigorous discovery measures[3] specific to patent litigation.

The Federal Circuit disagreed, finding that due diligence in discovering fraud is not about the lawyers’ lacking a requisite standard of care, but rather, the question is “whether a reasonable company in Cap Export’s position should have had reason to suspect the fraud … and, if so, took reasonable steps to investigate the fraud.”

Here, Cap Export met the requirement because there was no reason to suspect the fraud in the first place. Lawrie’s repeated denials in the deposition testimony, combined with the impossibility to reach the concealed evidence despite numerous search efforts by Cap Export and the general unavailability of such evidence, forestalled an initial suspicion of fraud which would otherwise call for further inquiry into the possible misconduct.

Opponent’s Fraud Preventing Fair and Full Defense

The Federal Circuit also found that the district court had not abuse its discretion in judging other parts of Rule 60(b)(3) jurisprudence.

As to the existence of fraud, the Federal Circuit approved the district court’s finding of affirmative misrepresentations. There is no clear error where the district court rejected Lawrie’s explanation that the false testimony arose from misunderstanding and was unintentional, which lacks credibility given the fact that the deposition occurred within a few years from the sales at issue.

As to the frustration of fairness and fullness, the Federal Circuit noted that Rule 60(b)(3) standard does not require showing that the result would have been different but for the fraudulently withheld information, but showing the evidence’s “likely worth” is sufficient to establish the harm. As such, the concealed prior art does not have to “qualify as invalidating prior art,” but being “highly material” suffices.

The Federal Circuit endorsed the district court’s judgment that the concealed evidence “would have been material” and its unavailability to Cap Export prevented it from fully and fairly presenting its case. The determination rests on the underlying factual findings that the on-sale prior art is “functionally identical in design” to the ‘123 patent claims, and that without the misrepresentations, the evidence would have been considered by the court in its obvious and anticipation analysis.

The Opinion’s closing remarks appear to suggest an implication of the procedural rules such as Rule 60(b)(3) in allowing the patent system to achieve its core purpose of serving the public interest. Legitimacy of patents is preserved by warding off fraudulent conduct in proceedings before the court, the establishment which works only where parties give entire information for a full and fair determination of their controversy.

Takeaway

- A favorable verdict procured through fraud will be vacated under Rule 60(b)(3).

- Due diligence requirement under Rule 60(b)(3) is unique to the Ninth Circuit. In cases involving the patentee’s knowledge about prior art, reasonableness in the patent challenger’s discovery and investigation tactics, even if they didn’t expose a lie, likely satisfies this additional requirement.

- To establish the evidentiary value of the concealed prior art in a Rule 60(b)(3) motion, a showing that the information is “highly material” to presenting the movant’s case, if not “invalidating” the patent, would be sufficient.

- In the present case, the second lawsuit filed by the patentee (i.e., the lying party) led to the discovery of its own fraud. What could the patent challenger have done to safeguard against the patentee’s lies in the first lawsuit? Perhaps taking patent-specific standard discovery measures such as those noted at footnote 3 might help. Watch out for a patentee’s past transactions involving products manufactured by a third party, which might be “highly material” on-sale prior art simply because of its functional or design similarity to the patent claims.

- After a final judgment is entered, a losing party may benefit from monitoring the opponent’s litigation activity involving the patent at issue, which might lead to discovery of previously unknown information, allowing for a potential Rule 60(b)(3) relief.

[1] And a third-party defendant added during the litigation. The parties on Cap Export’s side are referred to collectively as Cap Export.

[2] The Federal Circuit notes that the diligence requirement is at odds with the plain text of Rule 60(b)(3) and does not appear to be adopted in other regional courts of appeals. Compare Rule 60(b)(2), which states that “newly discovered evidence that, with reasonable diligence, could not have been discovered in time to move for a new trial.”

[3] Such as “[to] specifically seek prior art [in a written discovery request]; … [to] depose the inventor of the ’123 patent; and [to take] a deposition of Lawrie … [specifically] under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 30(b)(6).”