Depends On How You Slice It: CAFC reverses PTAB on Weber v. Provisur IPR ruling

| April 5, 2024

Weber, Inc. v. Provisur Tech. Inc.

Decided: February 8, 2024

Before Reyna, Hughes and Stark. Authored by Reyna

Summary: The Court reversed the PTAB’s finding that Weber’s instruction manuals did not qualify as printed publications under 35 USC §102. The Court also reversed key claim construction taken by the PTAB in upholding Provisur’s patents.

Background:

Provisur sued Weber for patent infringement on two patents, USP 10,639,812 (“’812 patent”) and 10,625,436 (“’436 patent”) relate to high-speed mechanical slicers used in food-processing plants. Weber countered by filing IPR proceedings against both patents at the USPTO Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). The PTAB found both the ‘812 and the ‘436 patentable. During the PTAB proceeding, Weber had attempted to use their own instruction manual for the slicer they sold as a prior art publication under 35 U.S.C. §102. The Board found that the instruction manual was not a “printed publication” under §102 on the basis that the manuals were controlled in their circulation to only customers or potential customers by a strict copyright and confidentiality clause.

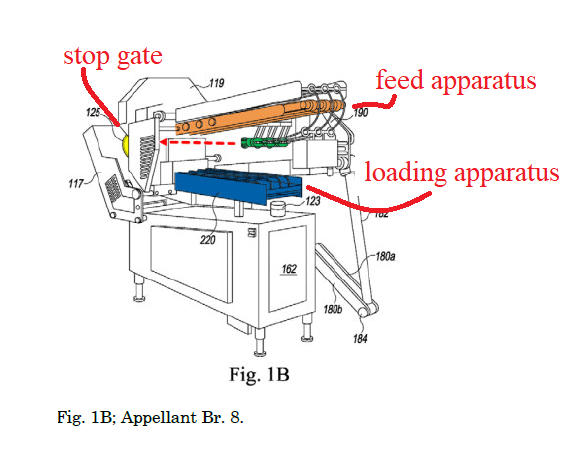

Further, the PTAB had construed three terms from the slicer components, (1) the “food article loading apparatus”; (2) the “food article feed apparatus”; and (3) the “food article stop gate” in a manner that maintained the patents’ validity while excluding the disclosures in Weber’s manuals.

Weber appealed the Board’s finding that their instruction manual was not a printed publication under §102 and the claim construction of the three terms.

Decision:

(a) Weber’s Instruction Manual as a “Printed Publication”

The Board had relied upon the CAFC’s prior holding in Cordis Corp. v. Boston Scientific Corp., 561 F.3d 1319 (Fed. Cir. 2009), in finding that Weber’s manuals were not “printed publications.” In Cordis, the references in question were two academic monographs describing an inventor’s work that were only distributed to a handful colleagues and two companies potentially interested in the technology.

The CAFC was quick to distinguish the current case from Cordis. First, the CAFC noted that the statutory phrase “printed publication” from § 102 has been defined to mean a reference that was “sufficiently accessible to the public interested in the art,” citing In re Klopfenstein, 380 F.3d 1345, 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2004) and that “public accessibility” was based on the relevant public being able to “locate the reference by reasonable diligence,” citing Valve Corp. v. Ironburg Inventions Ltd., 8 F.4th 1364, 1376 (Fed. Cir. 2021). Next, the Court found that Weber’s operating manuals were created for dissemination to the interested public to provide instructions for Weber’s slicer. The Court stated the Weber manuals were in “stark contrast” to the confidential monographs in Cordis which were subject to “academic confidentiality norms.” The Court went on to describe that the evidence provided by employees of Weber, stating that the manuals were readily provided to potential buyers, clearly indicated that the manuals did in fact qualify as “printed publications” under §102.

The Court also found the Board’s reliance on the copyright and confidentiality of Weber’s manuals to be misplaced. The Board had keyed in on the copyright language restricting the reproduction or transfer of the manuals and Weber’s “terms and conditions” stating that documents related to a sale of a slicer “remain the property of” Weber. The CAFC was not convinced that these statements made the manuals confidential to the point of not being a “printed publication”, stating:

Weber’s assertion of copyright ownership does not negate its own ability to make the reference publicly accessible. Cf. Correge v. Murphy, 705 F.2d 1326, 1328–30 (Fed. Cir. 1983) (“A mere assertion of ownership cannot convert what was in fact a public disclosure and offer to sell to numerous potential customers into a non-disclosure.”). The intellectual property rights clause from Weber’s terms and conditions covering sales, likewise, has no dispositive bearing on Weber’s public dissemination of operating manuals to owners after a sale has been consummated.

The Court reversed the PTAB’s finding that Weber’s instruction manuals were not “printed publications” within the meaning of 35 U.S.C. §102.

(b) Claim Construction – “disposed over” and “stop gate”

The Court next addressed the PTAB’s claim construction as to the term “disposed over” as used in the claims. The Board had construed the term “disposed over” to require that the “feed apparatus and its conveyor belts and grippers are ‘positioned above and in vertical and lateral alignment with’ the food article loading apparatus and its lift tray assembly.” The Court rejected this interpretation asserting that it reads elements into the claim which are not present. The Court noted that the specification and prosecution history did not impart any limited meaning to the term “disposed over” and therefore there was no basis for including the additional aspect that the feed apparatus and loading apparatus were in alignment. Citing Cyntec Co. v. Chilisin Elecs. Corp., 84 F.4th 979, 986 (Fed. Cir. 2023), the Court held that “Had the patent drafter intended to limit the claims” to address the alignment of the conveyor belts and lift tray assembly between the apparatuses, “narrower language could have been used in the claim.”

Running Provisur through the figurative slicer, the Court noted that Provisur did not dispute that Weber’s manuals satisfy the limitation under Weber’s proposed construction (i.e. that alignment is not required between the feed and loading apparatus). Hence, they concluded that their review of the Board’s claim construction is dispositive of the issue and that the Weber manuals do disclose the “disposed over” limitation.

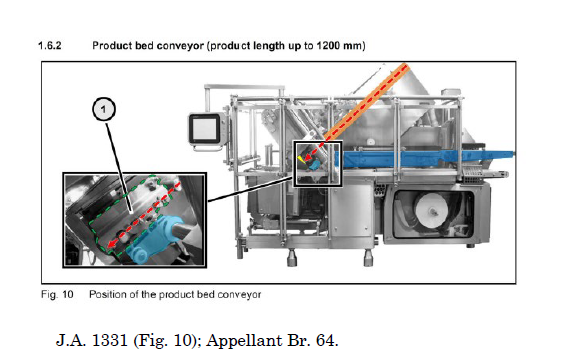

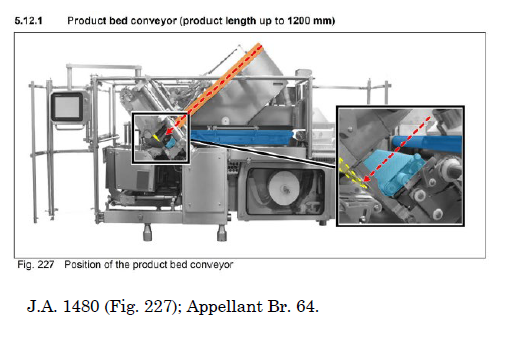

As to the “stop gate” term in the claims, Weber asserted that the Board erred in determining that the “product bed conveyer” disclosed in Weber’s operating manuals (as shown in Figures 10 and 227 thereof), does not disclose the “stop gate” limitation.

After analyzing the figures, the Court only commented that given these disclosures of the Weber manuals there was no substantial evidentiary support for the Board’s finding. Thus, the Court again reversed on the “stop gate” determinations.

Take aways:

- The Court clarifies the meaning of “printed publication” in 35 U.S.C. §102 by further defining the line between documents primarily intended to be confidential, such as the monographs in Cordis, and those primarily intended to be disseminated to the interested public, such as Weber’s manuals.

- By reversing the PTAB’s claim interpretation that had read a required alignment of parts into the claim where no such requirement was present, the Court also reiterates the standing law of claim construction that claim terms have their ordinary meaning unless intrinsic evidence demonstrates otherwise.