A small increase in a Prior Art’s taught range needs to have sufficient reason for the modification to establish obviousness under 35 U.S.C. §103

| August 6, 2021

Chemours Co. FC, LLC vs Daikin Ind., LTD

Decided on July 22, 2021

NEWMAN, DYK, and REYNA. Opinion by Reyna. Concurring and Dissenting in part by Dyk.

Summary:

Chemours Company FC, LLC, appealed the final written decisions of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board from two inter partes reviews brought by Daikan Industries, Ltd. Chemours argued on appeal that the Board erred in its obviousness factual findings and did not provide adequate support for its analysis of objective indicia of nonobviousness. The CAFC found that the Board’s decision on obviousness was not supported by substantial evidence and that the Board erred in its analysis of objective indicia of nonobviousness. Consequently, they reversed the Board’s decision.

Background:

Chemours Company FC, LLC, appealed the final written decisions of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board from two inter partes reviews brought by Daikan Industries, Ltd., et al. Chemours argues on appeal that the Board erred in its obviousness factual findings and did not provide adequate support for its analysis of objective indicia of nonobviousness.

Two patents were at issue. U.S. Patent No. 7,122,609 (the “’609 patent) and U.S. Patent No. 8,076,4312 (the “’431 patent”). The representative ’609 patent relates to a unique polymer for insulating communication cables formed by pulling wires through melted polymer to coat and insulate the wires, a process known as “extrusion.”

Claim 1 of the ’609 patent is representative of the issues on appeal:

1. A partially-crystalline copolymer comprising tetrafluoroethylene, hexafluoropropylene in an amount corresponding to a hexafluoropropylene index (HFPl) of from about 2.8 to 5.3, said copolymer being polymerized and isolated in the absence of added alkali metal salt, having a melt flow rate of within the range of about 30±3 g/10 min, and having no more than about 50 unstable end groups/106 carbon atoms.

The Board found all challenged claims of the ’609 patent and the ’431 patent to be unpatentable as obvious in view of U.S. Patent No. 6,541,588 (“Kaulbach”).

On appeal, Chemours argued that Daikin did not meet its burden of proof because it failed to show that a person of ordinary skill in the art (“POSA”) would modify Kaulbach’s polymer to achieve the claimed invention.

The Kaulbach reference teaches a polymer for wire and cable coatings that can be processed at higher speeds and at higher temperatures. Kaulbach highlights that the polymer of the invention has a “very narrow molecular weight distribution.” Kaulbach discovered that prior beliefs that polymers in high-speed extrusion application needed broad molecular weight distributions were incorrect because “a narrow molecular weight distribution performs better.” In order to achieve a narrower range, Kaulbach reduced the concentration of heavy metals such as iron, nickel and chromium in the polymer.

In the Kaulbach example relied on by the Board, Sample A11, Kaulbach’s melt flow rate is 24 g/10 min, while the claimed rate of Claim 1 of the ‘609 patent is 30±3 g/10 min.

The Board found that Kaulbach’s melt flow rate range fully encompassed the claimed range, and that a skilled artisan would have been motivated to increase the melt flow rate of Kaulbach’s preferred embodiment to within the claimed range to coat wires faster. Specifically, the Board found:

We also are persuaded that the skilled artisan would have been motivated to increase the [melt flow rate] of Kaulbach’s Sample A11 to be within the recited range in order to achieve higher processing speeds, because the evidence of record teaches that achieving such speeds may be possible by increasing a [polymer’s] [melt flow rate].

In addition, the Board found that the portions of Kaulbach’s disclosure lacked specificity regarding what is deemed “narrow” and “broad,” and that it would have been obvious to “broaden” the molecular weight distribution of the claimed polymer.

Second, Chemours argued that the Board legally erred in its analysis of objective indicia of nonobviousness by showings of commercial success finding an insufficient nexus between the claimed invention and Chemours’s commercial polymer, as the Board required market share evidence to show commercial success.

CAFC Decision:

- Obviousness and teaching away

The CAFC found that the Board ignored the express disclosure in Kaulbach that teaches away from the claimed invention and relied on teachings from other references that were not concerned with the particular problems Kaulbach sought to solve. In other words, the Board did not adequately grapple with why a skilled artisan would find it obvious to increase Kaulbach’s melt flow rate to the claimed range while retaining its critical “very narrow molecular-weight distribution.”

The Court maintained that the Board’s reasoning does not explain why a POSA would be motivated to increase Kaulbach’s melt flow rate to the claimed range, when doing so would necessarily involve altering the inventive concept of a narrow molecular weight distribution polymer. The Court held that this is particularly true in light of the fact that the Kaulbach reference appears to teach away from broadening molecular weight distribution and the known methods for increasing melt flow rate.

Specifically, Kaulbach includes numerous examples of processing techniques that are typically used to increase melt flow rate, which Kaulbach cautions should not be used due to the risk of obtaining a broader molecular weight distribution.

These factors do not demonstrate that a POSA would have had a “reason to attempt” to get within the claimed range, as is required to make such an obviousness finding.

As Chemours persuasively argues, the Board needed competent proof showing a skilled artisan would have been motivated to, and reasonably expected to be able to, increase the melt flow rate of Kaulbach’s polymer to the claimed range when all known methods for doing so would go against Kaulbach’s invention by broadening molecular weight distribution.

The CAFC therefore held that the Board relied on an inadequate evidentiary basis and failed to articulate a satisfactory explanation that is based on substantial evidence for why a POSA would have been motivated to increase Kaulbach’s melt flow rate to the claimed range, when doing so would necessarily involve altering the inventive concept of a narrow molecular weight distribution polymer.

- Commercial success

In addition, Chemours argued that the Board legally erred in its analysis of objective indicia of nonobviousness finding an insufficient nexus between the claimed invention and Chemours’s commercial polymer, and its requirement of market share evidence to show commercial success.

Specifically, Chemours argued that the Board improperly rejected an extensive showing of commercial success by finding no nexus on a limitation-by-limitation basis, rather than the invention as a whole. Chemours contended that the novel combination of these properties drove the commercial success of Chemours’s commercial polymer. Second, Chemours argued the Board improperly required Chemours to proffer market share data to show commercial success.

The CAFC held that contrary to the Board’s decision, the separate disclosure of individual limitations, where the invention is a unique combination of three interdependent properties, does not negate a nexus. The Court recognized that concluding otherwise would mean that nexus could never exist where the claimed invention is a unique combination of known elements from the prior art.

Further, the Court held, quoting prior caselaw, that the Board, erred in its analysis that gross sales figures, absent market share data, “are inadequate to establish commercial success.”

“When a patentee can demonstrate commercial success, usually shown by significant sales in a relevant market, and that the successful product is the invention disclosed and claimed in the patent, it is presumed that the commercial success is due to the patented invention.” J.T. Eaton & Co. v. Atl. Paste & Glue Co., 106 F.3d 1563, 1571 (Fed. Cir. 1997); WBIP, 829 F.3d at 1329. However, market share data, though potentially useful, is not required to show commercial success. See Tec Air, Inc. v. Denso Mfg. Mich. Inc., 192 F.3d 1353, 1360–61 (Fed. Cir. 1999).

The CAFC therefore reversed the Board’s finding of obviousness of the ‘609 and ‘431 claims at issue.

- Dissent

Judge Dyk dissented in part as to the strength of the teaching away by Kaulback. Specifically, he noted that Kaulbach’s copolymer is nearly identical to the polymer disclosed by claim 1 of the ’609 patent. The only material difference between claim 1 and Kaulbach is that Kaulbach discloses (in Sample A11) a melt flow rate of 24 g/10 min, slightly lower than 27 g/10 min, the lower bound of the 30 ± 3 g/10 min rate claimed in claim 1 of the ’609 patent.

As to the teachings of Kaulbach, he went on to note that even though Kaulbach determined that “a narrow molecular weight distribution performs better,” it expressly acknowledged the feasibility of using a broad molecular weight distribution to create polymers for high speed extrusion coating of wires. Hence, Judge Dyk concluded that this is not a teaching away from the use of a higher molecular weight distribution polymer.

Contrary to the majority’s assertion, modifying the molecular weight distribution of Kaulbach’s disclosure of a 24 g/10 min melt flow rate to achieve the 27 g/10 min melt flow rate of claim 1 would hardly “destroy the basic objective” of Kaulbach as the majority claims.

Take away

- There must be clear motivation for a POSA to modify a claimed range even to a small extent. Evidence within the prior art that such a modification would not be beneficial maybe a sufficient teaching away and can negate a finding of increasing the range as an obvious modification. Patent prosecutors should be more assertive in requiring a clear showing of reasons to make a modification of increasing a range outside of a prior art’s taught range.

Note Quite Game Over as Bot M8 Receive a 1-Up from the CAFC

| July 23, 2021

Bot M8 LLC., v. Sony Corporation of American, Sony Corporation, Cony Interactive Entertainment LLC.

Decided on July 13, 2021

Before Dyk, Linn and O’malley, Circuit Judges.

Opinion by Circuit Judge O’malley.

SUMMARY

Briefly, the CAFC addresses the stringency of pleading requirements in cases alleging patent infringement, and that patentees need not prove their case at the pleading stage. Further that “a patentee may subject its claims to early dismissal by pleading facts that are inconsistent with the requirements of its claims” Col. 2, L., 1 to 13.

DETAIL

Bot M8 LLC (herein Bot M8) filed suit against Sony et al (herein Sony) alleging infringement of six patents, five of which remain at issue. U.S. Patent Nos., 8,078,540, 8,095,990, 7,664,988, 8,112,670 and 7,338,363. The asserted patents relate to gaming machines. Bot M8 accused Sony’s PlayStation 4 (PS4) consoles and aspects of Sony’s network of infringing the ‘540, ‘990, ‘998 and ‘670 Patents, while certain PS4 videogames of infringing the ‘363 patent.

- Procedural History

Bot M8 initially sued Sony in the United States District Court for the Southern District of NY, Sony filed an answer, asserting non-infringement and arguing that “the Complaint fails to identify legitimate theories for how the claim limitations of the patent-in-suit are all allegedly satisfied,” along with a motion to transfer the case to California. Col 6, L., 1 to 6. Sony did not move to dismiss the complaint for failure to state a claim.

After the case was transferred, the district court held a case management conference, and the court directed Bot M8 to file an amended complaint specifying “every element of every claim that you say is infringed and/or explain why it can’t be done.” The court instructed Bot M8 that, “if this is a product you can buy on the market and reverse engineer, you have got to do that.” Id. Counsel for Bot M8 responded that they “would be happy to…” and that reverse engineering would not be a problem because it had already “torn down the Sony PlayStation.”

— First Amended Complaint (FAC)

Bot M8 timely filed a FAC, and Sony moved to dismiss. The district court held oral argument on Sony’s motion and at the hearing questioned why Bot M8 had not cited to Sony’s source code in the FAC, a failing Sony did not identify in its motion to dismiss. The Court specifically asked “Why can’t you buy one of these products and take whatever code is on there off and analyze it?” Bot M8 indicated that the PS4 source code is not publicly available.

Consequently, the district court granted Sony’s motion to dismiss as to the ’540, ’990, ’988 and ’670 patents.

Briefly, the district court held the following:

- For the ’990 patent—which describes a mutual authentication mechanism for video games—the court found that “the complaint fails to allege when or where the game program and mutual authentication program are stored together.”

- For the ‘540 patent—which describes an authentication mechanism for video games—the district court found that “the complaint fails to allege when or where the game program and authentication program are stored together on the same memory board.” Because the allegations “do not address where the game program is stored,” the court found them insufficient.

- For the ’988 and ’670 patents—which describe computer program fault inspection—the court found that “the complaint provides no basis to infer the proper timing of the inspection”—i.e., whether a “fault inspection program” is “completed before the game starts.” That Bot M8’s “allegation too closely tracks the claim language to be entitled to the presumption of truth,” and “[n]o underlying allegations of fact are offered.”

The district court explained that Bot M8 “already enjoyed its one free amendment under the rules” and was instructed to “plead well, element-by-element.” The court stated that Bot M8 “does not deserve yet another chance to re-plead,” but nevertheless gave Bot M8 another chance to do so. But added that, if Bot M8 “move[d] for leave to file yet another amended complaint, it should be sure to plead its best case.”

Next, during a discovery hearing, Bot M8 raised, for the first time, concerns about the legality of reverse engineering the PS4’s software, otherwise known as “jailbreaking,” under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (“DMCA”) and other anti-hacking statutes. The District Court asked Sony to give Bot M8 permission, and Sony agreed.

— Motion for Leave to Amend (Second Amended Complaint – SAC)

Bot M8 filed a motion for leave to amend its complaint and attached a redlined version of its proposed Second Amended Complaint (“SAC”). Bot M8 explained that the SAC was based on new evidence obtained only after Sony gave them permission to “jailbreak” the PS4.

Though Bot M8 moved for leave to file the SAC within the time frame authorized by the district court, the court still denied Bot M8’s motion for lack of diligence. Specifically, the court found that Bot M8 should have done the so-called “jailbreak” early in the proceedings and included the evidence in the FAC. The court explained that Bot M8’s motion was governed by FRCP 16, which authorized modifications “only for good cause.”

The district court found that Bot M8 “could have, and should have” included this evidence early because the issue of reverse engineering was brought up at the case management conference during which they failed to raise on concerns about the legality thereof. In fact, Bot M8’s counsel indicated they had already done it.

Consequently, the proposed amendment was deemed untimely.

—Motion to Reconsider

Bot M8 sought leave to move for reconsideration of the court’s order denying leave to amend, arguing that it could not have reverse engineered the PS4 before obtaining permission to disable the PS4’s access control technology in light of the DMCA.

The district court denied the motion, finding that Bot M8’s “theory of the [DMCA] crossing paths with patent rights remain[ed] unsupported by caselaw,” and Bot M8 “offer[ed] no binding decision directing a different pleading or amendment standard.”

—Summary Judgement under 35 U.S.C. §101

Sony moved for summary judgment of non-infringement and patent ineligibility under 35 U.S.C. § 101 against the ‘363 patent. In applying the two-part test set forth in Alice (Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International, 573 U.S. 208, 217– 18 (2014)) the district court found claim 1 of the ’363 patent ineligible.

At Alice step one, the court found that claim 1 recites “the abstract idea of increasing or decreasing the risk-to-reward ratio, or more broadly the difficulty, of a multiplayer game based upon previous aggregate results.” At Alice step two, the court concluded that “claim 1 offers no inventive concept.” That, “[t]hough given special names, each part remains a generic computer part invoked to effect the conventional computer task of gathering, manipulating, transmitting, and using data.”

Bot M8 has submitted two expert declarations to establish inventive step, but the court concluded that Bot M8’s expert testimony was insufficient “to forestall summary judgment,” because, for example, the experts failed to articulate any “specific inventive concept in claim 1… other than [a generic reference to] ‘the totality’” based expert report.

- CAFC

- Amending the Original Complaint: Bot M8 argued that the district court erred by “forcing” them to replace their original complaint. The CAFC disagreed, holding that the court merely gave Bot M8 a chance to amend, and Bot M8 chose to file an amended complaint rather than defend the original.

- Dismissal of the FAC: As per FRCP 8(a)(2) “generally requires only a plausible ‘short and plain’ statement of the plaintiff’s claim,” showing that the plaintiff is entitled to relief. Skinner, 562 U.S. at 530. To survive a motion to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(6), a complaint must “contain sufficient factual matter, accepted as true, to ‘state a claim to relief that is plausible on its face.’” Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662, 678 (2009) (quoting Bell v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544, 570 (2007)). “A claim has facial plausibility when the plaintiff pleads factual content that allows the court to draw the reasonable inference that the defendant is liable for the misconduct alleged.” Id. “Threadbare recitals of the elements of a cause of action, supported by mere conclusory statements, do not suffice.” Id. (citing Twombly, 550 U.S. at 555).

Initially, the CAFC disagreed with the districts approach of instructing Bot M8 that it must “explain in [the] complaint every element of every claim that you say is infringed and/or explain why it can’t be done.” The CAFC reiterated that a plaintiff “need not ‘prove its case at the pleading stage.’” That, a plaintiff is not required to plead infringement on an element-by-element basis.

Instead, it is enough “that a complaint place the alleged infringer ‘on notice of what activity . . . is being accused of infringement.’” Lifetime Indus., Inc. v. Trim-Lok, Inc., 869 F.3d 1372, 1379 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (quoting K-Tech Telecomms., Inc. v. Time Warner Cable, Inc., 714 F.3d 1277, 1284 (Fed. Cir. 2013)). See Twombly, 550 U.S. at 556 (“[A] well-pleaded complaint may proceed even if it strikes a savvy judge that actual proof of those facts is improbable, and that a recovery is very remote and unlikely.”)

Thus, “The relevant inquiry under Iqbal/Twombly is whether the factual allegations in the complaint are sufficient to show that the plaintiff has a plausible claim for relief. Iqbal, 556 U.S. at 679. “The plausibility standard is not akin to a ‘probability requirement,’ but it asks for more than a sheer possibility that a defendant has acted unlawfully.” Id. at 678. In other words, a plausible claim must do more than merely allege entitlement to relief; it must support the grounds for that entitlement with sufficient factual content. Id.” Col. 14, L., 4 to 13.

As such, the Plaintiff “cannot assert a plausible claim for infringement under the Iqbal/Twombly standard by reciting the claim elements and merely concluding that the accused product has those elements. There must be some factual allegations that, when taken as true, articulate why it is plausible that the accused product infringes the patent claim.” Col. 14, L 22 to 28. That is, a Plaintiff is to “give the defendant fair notice of what the . . . claim is and the grounds upon which it rests,” Erickson v. Pardus, 551 U.S. 89, 93 (2007) (quoting Twombly, 550 U.S. at 555).

Having clarified the standard, the CAFC concluded that they agreed with the district court that the allegations as to the ‘540 and ‘990 patents were conclusory, and at times contradictory but disagreed with the dismissal of the ‘988 and ‘670 patents. Here, the CAFC emphasized that the “court simply required too much.”

Briefly, the CAFC held the following:

- For the ’990 patent—which describes a mutual authentication mechanism for video games—the CAFC agreed with the district counts analyzing that found “the complaint fails to allege when or where the game program and mutual authentication program are stored together.”

- For the ‘540 patent—which describes an authentication mechanism for video games—the CAFC agreed with Sony that the FAC actually alleges away from infringement by asserting that the purported “authentication program” is stored on the PS4 motherboard—an allegation that is inconsistent with Bot M8’s infringement theory. That CAFC noted that Bot M8 had taken a “kitchen sink” approach in their complaint, revealing inconsistencies that ended up being fatal.

- For the ’988 and ’670 patents—which describe computer program fault inspection—and completed the inspection before the game starts. Here, the CAFC differed with the district court. Bot M8 argued on appeal that the district court erred in its dismissal because the FAC “includes specific evidence demonstrating that the PS4 includes a fault inspection program that concludes prior to the game starting.” That is, the PS4 displays error codes upon boot up and prior to a game starting, and the CAFC agreed this supports a plausible inference that the PS4’s fault inspection program concluded prior to the start of a game. Sony argued, and the district court agreed, that these passages failed to allege that execution of a fault inspection program completes before a game start, only that they commence during start-up. That CAFC held that Sony, like the district court, “demands too much as this stage of proceedings.”

- Denial of Leave to Amend the FAC: The CAFC ultimately determined that the denial was proper, because Bot M8 did not raise any concerns about its ability to reverse engineer the PS4 until after the district court issued its decision on Sony’s motion to dismiss, thus Bot M8 was not diligent.

Of note, the CAFC stated that while the district court perhaps should not have required reverse engineering of Sony’s products as a prerequisite to pleading claims of infringement, Bot M8 ultimately waived its objection to that obligation when it told the court it was happy to undertake that exercise.

- The ‘363 Patent: After consideration, the CAFC found no error in the districts 101 analysis.

CONCLUSION: Affirmed in part, reversed in part and remanded to the district court for further proceedings regarding infringement of the ’988 and ’670 patents.

- Take-Aways:

- Patentees need not prove their case as the pleading stage. But there must be some factual allegations that, when taken as true, articulate why it is plausible that the accused product infringes the patent claim.

- A patentee may subject its claims to early dismissal by pleading fats that are inconsistent with the requirements of its claims. As here, be mindful of “kitchen sink” approached, that arguments do not end up inconsistent.

- Be mindful of comments made during pre-trail procedures and always strive to be timely. Here, Bot M8’s counsel stated during the case management conference that their client was happy to reverse engineer the PS4 and had already done it, which turned out to be untrue and thus their wait of around 9 weeks to seek authorization to reverse engineer the product provide fatal for a lack of diligence. This ultimately lead to Bot M8 waiving its objection to this obligation.

The “inferior” Board: Supreme Court preserves the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, but empowers the PTO Director with final decision-making authority over Board proceedings

| July 13, 2021

United States v. Arthrex, Inc. (also, Smith & Nephew, Inc. v. Arthrex, Inc., Arthrex, Inc. v. Smith & Nephew, Inc.) (Supreme Court)

Decided on June 21, 2021

Chief Justice Roberts wrote the opinion of the Court, with Justices Alito, Thomas, Breyer, Sotomayor, Kagan, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett variously concurring and dissenting.[1]

Summary

In U.S. v. Arthrex, the U.S. Supreme Court confirmed that the Administrative Patent Judges (APJs) of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board are improperly appointed in violation of the Appointments Clause of the Constitution. The Court held that 35 U.S.C. §6(c), which provided that only the Board may grant a rehearing of a final decision arising out of an inter partes review proceeding, was unenforceable insofar as the provision denied the Director the power to review the Board’s decision. To cure the constitutional infirmity, the Court held that the correct remedy was to require that the Director review decisions by APJs.

Details

When Arthrex, Inc. saw their U.S. Patent No. 9,179,907 being invalidated by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, in an inter partes review brought by Smith & Nephew, Inc., they appealed to the Federal Circuit, challenging not only the substance of the Board’s Final Written Decision, but also the constitutionality of the Board. Arthrex argued that the appointment of the Administrative Patent Judges (APJs) violated the Appointments Clause of the Constitution. And being unconstitutionally appointed, the APJs had no authority to deprive Arthrex of their rights in their patent.

Arthrex’s constitutionality argument might have started out as a long-shot. It was the last of their four arguments on appeal, and occupied only 7 of their 149-page opening brief. Remarkably, it was the one that brought Arthrex the most success.

The Appointments Clause (Art. II, §2, cl. 2) of the Constitution provides that principal officers in the U.S. government must be appointed by the President “and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate”. But the Appointments Clause also provides that inferior officers may be appointed by “the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.”

The America Invents Act of 2011 established the Patent and Trial Appeal Board as a tribunal within the Executive Branch. The Board sits in panels of at least three members drawn from the PTO Director, PTO Deputy Director, the Commissioner for Patents, the Commissioner for Trademarks, and APJs. The Secretary of Commerce appoints the members of the Board, except for the Director, who is appointed by the President.

On appeal at the Federal Circuit, the principal question was whether APJs were principal officers or inferior officers, the former requiring appointment by the President as opposed to the Secretary of Commerce.

To answer the question, the Federal Circuit looked mainly to Edmonds v. United States, 520 U.S. 651 (1997).

In Edmonds, the Supreme Court explained that “[w]hether one is an ‘inferior’ officer depends on whether he has a superior”, and “‘inferior officers’ are officers whose work is directed and supervised at some level by others who were appointed by Presidential nomination with the advice and consent of the Senate”. Edmonds, 520 U.S. at 662-63. The Supreme Court in Edmonds articulated three factors that aided in distinguishing between principal and inferior officers: (1) whether an appointed official has the power to review and reverse the officers’ decision; (2) the level of supervision and oversight an appointed official has over the officers; and (3) the appointed official’s power to remove the officers. Id. at 664-65. The central consideration was the “extent of direction or control” that the appointed officials had over the officers, because the objective was to preserve the chain of command down from the President, so that “political accountability” may be preserved. Id. at 663.

Following Edmonds,the Federal Circuit found that APJs were principal officers due to the lack of any presidentially appointed officials who could review decisions by APJs, as well as the lack of unfettered authority on the part of the Secretary of Commerce and Director to remove APJs at will. Because APJs were found to be principal officers, their appointments by the Secretary of Commerce, instead of the President, violated the Appointments Clause.

Having found a constitutional violation, the Federal Circuit then fashioned a remedy that severed and invalidated the statutory limitations on the removal of APJs. The Federal Circuit reasoned that making APJs removable at will would render them inferior officers. The Federal Circuit also determined that, because the invalidity decision against Arthrex’s patent was issued by an unconstitutionally appointed Board, the decision must be vacated and remanded to the Board for a fresh hearing before a panel of new, constitutionally appointed APJs.

“This satisfied no one”, as the Supreme Court reflected in U.S. v. Arthrex.

All the parties involved in the Federal Circuit appeal—the government, Arthrex, Smith & Nephew—requested the Court’s review of different aspects of the Federal Circuit’s decision.

Nevertheless, the question before the Court was the same one that faced the Federal Circuit: “[W]hether the PTAB’s structure is consistent with the Appointments Clause, and the appropriate remedy if it is not.”

In a divided 5-4 decision, the Court agreed with the Federal Circuit that APJs were unconstitutionally appointed, but disagreed with the Federal Circuit on the appropriate remedy.

The Court began with the premise that “Congress provided that APJs would be appointed as inferior officers, by the Secretary of Commerce as head of a department”. However, the nature of the APJs’ authority was such that they were really acting as principal officers.

The problem was the lack of supervision over the APJs’ decision-making:

What was “significant” to the outcome [in Edmonds]—review by a superior executive office—is absent here: APJs have the “power to render a final decision on behalf of the United States” without any such review by their nominal superior or any other principal officer in the Executive Branch. The only possibility of review is a petition for rehearing, but Congress unambiguously specified that “[o]nly the Patent and Trial Appeal board may grant rehearings.” [35 U.S.C. § 6(c)]. Such review simply repeats the arrangement challenged as unconstitutional in this suit.

The current setup “diffuses” accountability. The Court recognized that “[he, the Director] is the boss” of APJs in most ways, but the Court was troubled by the Director’s powerlessness over the one source of APJs’ “significant authority”—their power to issue decisions on patentability. In that regard, the Director is relegated to the ministerial duty of issuing a certificate canceling or confirming patent claims. As the Court noted, “[t]he chain of command runs not from the Director to his subordinates, but from the APJs to the Director”.

The government attempted to drum up the Director’s influence over the Board’s decision-making. The government argued that it was the Director who decided whether to initiate inter partes reviews, who could designate APJs predisposed to his views to hear a case, who could vacate an institution decision “if he catches wind of an unfavorable ruling on the way” as long as he intervened before a final written decision, who could “manipulate the composition of the PTAB panel that acts on the rehearing petition”, who could “‘stack’ the panel at rehearing, and who could appoint himself to a panel to reverse a decision at rehearing.

Putting aside the troubling due process and fairness concerns raised by the alleged influences of the Director, the Court criticized the government for creating “a roadmap for the Director to evade a statutory prohibition on review [i.e., 35 U.S.C. § 6(c)] without having him take responsibility for the ultimate decision”:

Even if the Director succeeds in procuring his preferred outcome, such machinations blur the lines of accountability demanded by the Appointments Clause. The parties are left with neither an impartial decision by a panel of experts nor a transparent decision for which a politically accountable officer must take responsibility. And the public can only wonder “on whom the blame or the punishment of a pernicious measure, or series of pernicious measures ought really to fall.”

All this led to the Court’s conclusion that “the unreviewable authority wielded by the APJs during inter partes review is incompatible with their appointment by the Secretary to an inferior office”.

For a solution, the Court disagreed with the Federal Circuit that at-will removal of APJs was the answer. The unconstitutionality of the APJs’ appointments lay in the unreviewability of their decisions, and the Federal Circuit’s proposed solution did not adequately address that problem. The solution must instead empower the Director to review Board decisions:

In our view, however, the structure of the PTO and the governing constitutional principles chart a clear course: Decisions by APJs must be subject to review by the Director.

More particularly, the Court explained that:

The upshot is that the Director cannot rehear and reverse a final decision issued by APJs. If the Director were to have the “authority to take control” of a PTAB proceeding, APJs would properly function as inferior officers.

We conclude that a tailored approach is the appropriate one: Section 6(c) cannot constitutionally be enforced to the extent that its requirements prevent the Director from reviewing final decisions rendered by APJs….The Director may accordingly review final PTAB decisions and, upon review, may issue decisions himself on behalf of the Board. Section 6(c) otherwise remains operative as to the other members of the PTAB.

The Director’s decision is then subject to judicial review:

When reviewing such a decision by the Director, a court must decide the case “conformably to the constitution, disregarding the law” placing restrictions on his review authority in violation of Article II.

Finally, the Court vacated the Federal Circuit’s decision to grant Arthrex a hearing before a new panel of APJs. The Court found sufficient their remedy of a limited remand to the Director to determine whether to rehear Smith & Nephew’s inter partes review petition.

There are few interesting aspects to the Court’s Arthrex opinion.

The Court’s holding is narrow. It applies only to 35 U.S.C. §6(c), which currently provides that “[o]nly the Patent Trial and Appeal Board may grant rehearings”, and only to the extent that section 6(c) prohibits the Director from reviewing the Board’s decisions. The holding also applies only to inter partes reviews—the Court is explicit that “[w]e do not address the Director’s supervision over other types of adjudications conducted by the PTAB, such as the examination process for which the Director has claimed unilateral authority to issue a patent”.

In other words, the Court’s decision is unlikely to bring any radical changes to the Board.

It is also notable that Chief Justice Roberts wrote the majority opinion in Arthrex. In Oil State energy Services, LLC v. Greene’s Energy Group, LLC, 138 S.Ct. 1365 (2018), the Supreme Court held that patent grants involved public rights and the Board’s adjudication of patents without a jury, despite not being an Article III tribunal, was constitutionally permissible. But Chief Justice Roberts joined in the dissenting opinion in that case. The dissent was resolute that the Director and the Board, that is, “a politically appointee and his administrative agents, instead of an independent judge”, should not be permitted to adjudicate patents. Id. at 1380. That is, patent adjudication should be insulated from politics. During the oral argument in Oil State, Chief Justice Roberts raised due process concerns over the Director’s ability to influence Board decisions through panel stacking.

Yet, in Arthrex, Chief Justice Roberts would give the politically appointed Director plenary power to review, modify, and even nullify a Board decision, potentially making the Board vulnerable to political influences. How can Chief Justice Roberts’ positions in Oil State and Arthrex be reconciled?

The Court’s decision in Arthrex also touches on the complex relationship between the PTO, which is an agency, the Board, which is an adjudicatory within the agency, and the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) that is supposed to govern their actions.

The Federal Circuit has suggested in the past that proceedings before the Board are APA-governed formal adjudication subject to the formal adjudication procedures set forth in 5 U.S.C. §§556-557. However, the Court in Arthrex suggested that Board proceedings were actually “adjudication that takes place outside the confines of §557(b)”. If Board proceedings are not subject to the APA, then what, if any, regulatory scheme governs Board proceedings to ensure procedural fairness?

In addition, the plain language of the statutes seems to already authorize the Director to grant rehearings. Section 6(a) provides that “[t]he Director, the Deputy Director, the Commissioner for Patents, the Commissioner for Trademarks, and the administrative patent judges shall constitute the Patent Trial and Appeal Board”, and section 6(c) provides that “[o]nly the Patent Trial and Appeal Board may grant rehearings”. Is the Court really rewriting the statute by giving the Director reviewing powers? Or is the Court merely making explicit what Congress had already intended?

Interestingly, the Court’s opinion referred to the Trademark Modernization Act of 2020, which makes explicit that “the authority of the Director…includes the authority to reconsider, and modify or set aside, a decision of the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board”. The Trademark Modernization Act of 2020 thus shields the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board from copycat constitutional challenges.

What now?

The PTO will now need to issue guidance on how the Court’s holding will be implemented. The PTO’s existing Standard Operating Procedure 2[2] appears to provide a procedural framework for requesting rehearing by the Director, as the SOP2 already establishes the Director’s authority to convene a “Precedential Opinion Panel” to review decisions in cases before the Board and determine, in the Director’s sole discretion, whether to order sua sponte rehearing.

The PTO has its work cut out. Following the Federal Circuit’s decision in Arthrex, Inc. v. Smith & Nephew, Inc., the Chief Administrative Patent Judge of the Board issued a general order holding in abeyance more than 100 Board decisions from post-grant proceedings, which were remanded as a result of the Federal Circuit’s Arthrex decision. See General Order in Cases Remanded under Arthrex, Inc. v. Smith & Nephew, Inc., 941 F.3d 1320 (Fed. Cir. 2019) (Boalick, Chief APJ, PTAB, May 2020).

Also complicating the situation is the current absence of a Director at the PTO. Is a Commissioner of Patent, serving as an Acting Director, constitutionally authorized to review and potentially modify Board decisions? Can the Secretary of Commerce step in while the PTO awaits a new Director?

[1] This review will focus only on the majority opinion.

[2] https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/SOP2%20R10%20FINAL.pdf.

Tags: administrative patent judge > Administrative Procedure Act > Constitutional Law > Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) > Supreme Court

DOCTRINE OF PROSECUTION DISCLAIMER ENSURES THAT CLAIMS ARE NOT CONSTRUED ONE WAY TO GET ALLOWANCE AND IN A DIFFERENT WAY TO AGAINST ACCUSED INFRINGERS

| July 8, 2021

SpeedTrack, Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc. et al.

Decided on June 3, 2021

Prost (author), Bryson, and Reyna

Summary:

The Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s claim construction orders regarding the hierarchical limitations recited in the SpeedTrack’s ’360 patent based on Applicants’ arguments and claim amendments made during the prosecution of the ’360 patent.

Details:

The ’360 patent

SpeedTrack owns U.S. Patent No. 5,544,360 (“the ’360 patent), which is directed to providing “a computer filing system for accessing files and data according to user-designated criteria.” The ’360 patent discusses that prior-art systems “employ a hierarchical filing structure” which could be very cumbersome when the number of files are large or file categories are not well-defined. In addition, the ’360 patent discusses that some prior-art systems are subject to errors when search queries are mistyped and restricted by the field of each data element and the contents of each field.

However, the ’360 patent discloses a method that uses “hybrid” folders, which “contain those files whose content overlaps more than one physical directory,” for providing freedom from the restrictions caused by hierarchical and other computer filing systems.

Representative claim 1 recites a three-step method: (1) creating a category description table containing category descriptions (having no predefined hierarchical relationship with such list or each other); (2) creating a file information directory as the category descriptions are associated with files; and (3) creating a search filter for searching for files using their associated category descriptions.

1. A method for accessing files in a data storage system of a computer system having means for reading and writing data from the data storage system, displaying information, and accepting user input, the method comprising the steps of:

(a) initially creating in the computer system a category description table containing a plurality of category descriptions, each category description comprising a descriptive name, the category descriptions having no predefined hierarchical relationship with such list or each other;

(b) thereafter creating in the computer system a file information directory comprising at least one entry corresponding to a file on the data storage system, each entry comprising at least a unique file identifier for the corresponding file, and a set of category descriptions selected from the category description table; and

(c) thereafter creating in the computer system a search filter comprising a set of category descriptions, wherein for each category description in the search filter there is guaranteed to be at least one entry in the file information directory having a set of category descriptions matching the set of category descriptions of the search filter.

District Court

In September of 2009, SpeedTrack sued retail website operations for infringement of the ’360 patent. The Northern District construed the hierarchical limitation with the below construction (relied in part on disclaimers made during prosecution):

The category descriptions have no predefined hierarchical relationship. A hierarchical relationship is a relationship that pertains to hierarchy. A hierarchy is a structure in which components are ranked into levels of subordination; each component has zero, one, or more subordinates; and no component has more than one superordinate component.

After that, SpeedTrack moved to clarify the district court’s construction regarding prosecution-history disclaimer.

Subsequently, the district court issued a second claim construction order by adding the following clarification in its first order:

Category descriptions based on predefined hierarchical field-and-value relationships are disclaimed. “Predefined” means that a field is defined as a first step and a value associated with data files is entered into the field as a second step. “Hierarchical relationship” has the meaning stated above. A field and value are ranked into levels of subordination if the field is a higher-order description that restricts the possible meaning of the value, such that the value must refer to the field. To be hierarchical, each field must have zero, one, or more associated values, and each value must have at most one associated field.

In order to support its second claim construction order, the district court analyzed SpeedTrack’s prosecution statements (for their clear disavowal of category descriptions based on hierarchical field-and-value relationships).

The Federal Circuit

The CAFC handled the issue of claim construction.

SpeedTrack acknowledged that the hierarchical limitation was added during the prosecution of the ’360 patent to overcome the Schwartz reference.

During the prosecution, Applicants distinguished their invention from Schwartz by arguing that “unlike prior art hierarchical filing systems, the present invention does not require the 2-part hierarchical relationship between fields or attributes, and associated values for such fields or attributes.”

In addition, Applicants argued that “the present invention is a non-hierarchical filing system that allows essentially ‘free-form’ association of category descriptions to files without regard to rigid definitions of distinct fields containing values.”

Finally, Applicants argued that “this distinction has been clarified in the claims as amended by the addition of the following language in all of the claims: ‘each category description comprising a descriptive name, the category descriptions having no predefined hierarchical relationships with such list or each other.’”).

The CAFC agreed with the district court’s assessment that predefined field-and-value relationships are excluded from the claims.

The CAFC disagreed with SpeedTrack’s argument that the “category descriptions” of the ’360 patent are not the fields of Schwartz and that the hierarchical limitation precludes predefined hierarchical relationships only among category descriptions.

SpeedTrack argued that Applicants distinguished Schwartz on other grounds. However, the CAFC did not agree with this argument.

In addition, the CAFC noted that SpeedTrack’s position contradicts its other litigation statements. “Ultimately, the doctrine of prosecution disclaimer ensures that claims are not ‘construed one way in order to obtain their allowance and in a different way against accused infringers.’” Aylus Networks, Inc. v. Apple Inc., 856 F.3d 1353, 1360 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (quoting Southwall Techs., Inc. v. Cardinal IG Co., 54 F.3d 1570, 1576 (Fed. Cir. 1995)).

Finally, the CAFC noted that both of the first and second construction orders acknowledged the disclaimer.

Therefore, the CAFC affirmed the district court’s final judgement of noninfringement.

Takeaway:

- Applicants need to be careful about claim amendments and arguments made during the prosecution of their patents.

- Litigation statements, while not inventors’ prosecution statements and do not demonstrate prosecution-history disclaimer, can strengthen the court’s reasonings on the prosecution history.

Revisiting KSR: “A person of ordinary skill is also a person of ordinary creativity, not an automaton.”

| June 29, 2021

Becton, Dickinson and Company v. Baxter Corporation Englewood

Decided on May 28, 2021

Prost*, Clevenger, and Dyk. Court opinion by Dyk. (*Sharon Prost vacated the position of Chief Judge on May 21, 2021, and Kimberly A. Moore assumed the position of Chief Judge on May 22, 2021.)

Summary

On appeals from the United States Patent and Trademark Office, Patent Trial and Appeal Board in an inter partes review, the Federal Circuit unanimously revered the Board’s conclusion of non-obviousness of an asserted patent, directed to a “method for performing telepharmacy,” and a “system for preparing and managing patient-specific dose orders that have been entered into a first system.” The Federal Circuit stated that, in analysis of obviousness, a person of ordinary skill would also consider a source other than cited prior art references, and established that cancellation of all the claims of a patent does not affect the status of the patent as pre-AIA Section 102(e)(2) reference.

Details

I. Background

Becton, Dickinson and Company (“Becton”) petitioned for inter partes review of claims 1– 13 and 22 of U.S. Patent No. 8,554,579 (“the ’579 patent”), owned by Baxter Corporation Englewood (“Baxter”).

Becton asserted invalidity of the challenged claims primarily based on three prior art references: U.S. Patent No. 8,374,887 (“Alexander”), U.S. Patent No. 6,581,798 (“Liff”), and U.S. Patent Publication No. 2005/0080651 (“Morrison”).

Claims 1 and 8 are illustrative of the ’579 patent, as agreed by the parties. Claim 1 is directed to a “method for performing telepharmacy,” and claim 8 is directed to a “system for preparing and managing patient-specific dose orders that have been entered into a first system.”

There are two contested limitations on appeal: the “verification” limitation in claim 8, and the “highlighting” limitation in claims 1 and 8. Claim 8 recites three elements, an order processing server, a dose preparation station, and a display. The relevant portion of the dose preparation station in claim 8, containing both limitations, reads:

8. A system for preparing and managing patient-specific dose orders that have been entered into a first system, comprising:

a dose preparation station for preparing a plurality of doses based on received dose orders, the dose preparation station being in bi-directional communication with the order processing server and having an interface for providing an operator with a protocol associated with each received drug order and specifying a set of drug preparation steps to fill the drug order, the dose preparation station including an interactive screen that includes prompts that can be highlighted by an operator to receive additional information relative to one particular step and includes areas for entering an input;

. . . and wherein each of the steps must be verified as being properly completed before the operator can continue with the other steps of drug preparation process, the captured image displaying a result of a discrete isolated event performed in accordance with one drug preparation step, wherein verifying the steps includes reviewing all of the discrete images in the data record . . . .

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) determined that asserted claims were not invalid as obvious. While the Board found that Becton had established that one of ordinary skill in the art would have been motivated to combine Alexander and Liff, as well as Alexander, Liff, and Morrison, and that Baxter’s evidence of secondary considerations was weak, the Board nevertheless determined that Alexander did not teach or render obvious the verification limitation and that combinations of Alexander, Liff, and Morrison did not teach or render obvious the highlighting limitation.

Becton appealed.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit (“the Court”) unanimously revered the Board’s conclusion of non-obviousness because the determination regarding the verification and highlighting limitations is not supported by substantial evidence.

(i) The Verification Limitation

Alexander discloses in a relevant part: “[I]n some embodiments, a remote pharmacist may supervise pharmacy work as it is being performed. For example, in one embodiment, a remote pharmacist may verify each step as it is performed and may provide an indication to a non-pharmacist per- forming the pharmacy that the step was performed correctly. In such an example, the remote pharmacist may provide verification feedback via the same collaboration software, or via another method, such as by telephone.” Alexander, col. 9 ll. 47–54 (emphasis added).

Relying on the above-cited portion of Alexander, the Board found persuasive Baxter’s argument that Alexander “only discusses that ‘a remote pharmacist may verify each step’; not that the remote pharmacist must verify each and every step before the operator is allowed to proceed” (emphasis added).

The Court concluded that the Board’s determination that Alexander does not teach the verification limitation is not supported by substantial evidence because, among other things, the Court found it quite clear that “[i]n the context of Alexander, “may” does not mean “occasionally,” but rather that one “may” choose to systematically check each step.”

(ii) The Highlighting Limitation

Becton did not argue that Liff “directly discloses highlighting to receive additional language about a drug preparation step.” Instead, Becton argued that “Liff discloses basic computer functionality—i.e., using prompts that can be highlighted by the operator to receive additional information—that would render the highlighting limitation obvious when applied in combination with other references,” primarily Alexander.

In support of petition for inter partes review, Dr. Young testified in his declaration that Liff “teaches that the user can highlight various inputs and information displayed on the screen, as illustrated in Figure 14F.”

The Board found that Liff taught “highlight[ing] patient characteristics when dispensing a prepackaged medication.” Baxter did not contend that this aspect of the Board’s decision was erroneous.

Nevertheless, while finding that “this present[ed] a close case,” the Board determined, that “Dr. Young fail[ed] to explain why Liff’s teaching to highlight patient characteristics when dispensing a prepackaged medication would lead one of ordinary skill to highlight prompts in a drug formulation context to receive additional information relative to one particular step in that process, or even what additional information might be relevant.” In addition, the Board found that Becton’s arguments with respect to Morrison did not address the deficiency in its position based on Alexander and Liff.

In contrast, citing KSR (“[a] person of ordinary skill is also a person of ordinary creativity, not an automaton”), the Court concluded that the Board erred in looking to Liff as the only source a person of ordinary skill would consider for what “additional information might be relevant.” The Court reached an opposite conclusion by citing following Dr. Young’s testimony:

“[a] person of ordinary skill in the art would have understood that additional information could be displayed on the tabs taught by Liff” and that “such information could have included the text of the order itself, information relating to who or how the order should be prepared, or where the or- der should be dispensed.”

“[a] medication dose order for compounding a pharmaceutical would have been accompanied by directions for how the dose should be prepared, including step-by-step directions for preparing the dose.”

(iii) An Alternative Ground

As an alternative ground to affirm the Board’s determination of non-obviousness, Baxter argues that the Board erred in determining that Alexander is prior art under 35 U.S.C. § 102(e)(2) (pre-AIA).

It is undisputed that the filing date of the application for Alexander is February 11, 2005, which is before the earliest filing date of the application for the ’579 patent, October 13, 2008; that the Alexander claims were granted; and that the application for Alexander was filed by another.

However, based on the fact that all claims in Alexander (granted on February 12, 2013) were cancelled on February 15, 2018, following inter partes review, Baxter argued that “because the Alexander ‘grant’ had been revoked, it can no longer qualify as a patent ‘granted’ as required for prior art status under Section 102(e)(2).”

The Court rejected Baxter’s argument because “[t]he text of the statute requires only that the patent be “granted,” meaning the “grant[]” has occurred. 35 U.S.C. § 102(e)(2) (pre-AIA)” and “[t]he statute [thus] does not require that the patent be currently valid.”

(iv) Secondary Considerations

The Court rejected Baxter’s argument because “Baxter does not meaningfully argue that the weak showing of secondary considerations here could overcome the showing of obviousness based on the prior art.”

Takeaway

· In analysis of obviousness, a person of ordinary skill would also consider a source other than cited prior art references (petitioner’s testimony in this case).

· Cancellation of all the claims of a patent does not affect the status of the patent as pre-AIA Section 102(e)(2) reference.

No likelihood of confusion with the mark BLUE INDUSTRY and opposer’s numerous marks having INDUSTRY as an element

| June 25, 2021

Pure & Simple Concepts, Inc. v. I H W Management Limited, DBA Finchley Group (non-precedential)

Decided on May 24, 2021

Moore, Reyna, Chen (opinion by Reyna)

Summary

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“the CAFC”) affirmed the Board’s determination of no likelihood of confusion or dilution between numerous marks of Pure & Simple Concepts, Inc. (hereinafter “P&S”) having the shared term “INDUSTRY” and “BLUE INDUSTRY” mark of I H W Management Limited, d/b/a The Finchley Group (hereinafter “Fincley”).

Details

P&S owns eight registered trademarks which all use the word “INDUSTRY” and licenses the use of these marks in connection with apparel items. On April 30, 2015, Finchley filed an application to register the mark BLUE INDUSTRY for various clothing items. P&S opposed registration of Finchley’s mark under Section 2(d) and 43(c) of the Lanham Act on the grounds of likelihood of confusion and likelihood of dilution by blurring based on P&S’s previous use and registration of its numerous INDUSTRY marks. The Board dismissed the opposition, finding that P&S failed to prove a likelihood of confusion, and that P&S failed to establish the critical element of fame for dilution.

P&S appealed to the CAFC, contending that the Board erred by (1) not considering all relevant DuPont factors; (2) determining the word “BLUE” to be the dominant term in Finchley’s mark; (3) relying heavily on third-party registrations; and (4) failing to find P&S’s family of marks as being famous.

First, in arguing that the Board erred by not considering all relevant DuPont factors, P&S contended that the Board did not consider that clothing items are more likely to be purchased on an impulse, and therefore, consumers are more likely to be confused. Finchley argued that this argument concerns the DuPont factor 4, which P&S presented no evidence before the Board. The CAFC agreed with Finchley, finding that P&S failed to present the evidence, and accordingly, P&S forfeited argument as to this factor.

Next, P&S contended that the Board erred in concluding that “BLUE” is the dominant term in the commercial impression created by Finchley’s mark. While it is not proper to dissect a mark, “one feature of a mark may be more significant than other features, and [thus] it is proper to give greater force and effect to that dominant feature.” Giant Food, Inc. v. Nation’s Foodservice, Inc., 710 F.2d 1565, 1570 (Fed. Cir. 1983). P&S cited as an example, Trump v. Caesars World, Inc., 645 F. Supp. 1015, 1019 (D.N.J. 1986), where the second word, “Palace,” was found to be dominant in the marks TRUMP PALACE and CEASER’S PALACE. However, the CAFC determined that the Board’s finding that BLUE to be the lead term in Finchley’s mark, and that the term BLUE is most likely to be impressed upon the minds of the purchasers and be remembered was supported by substantial evidence.

Third, P&S argued that the Board erred by heavily relying on third-party registrations. P&S argued that some of these third-party registrations were listed twice, some were canceled, some had no evidence of use, and some listed different goods. Nevertheless, the CAFC affirmed that the term “INDUSTRY,” or the plural thereof, has been registered by numerous third parties to identify clothing and apparel items, and therefore, the term is weak, and the scope is limited as applied to clothing items.

Finally, as to P&S’s dilution claim, the Board determined that the number of registered marks by third parties having the INDUSTRY element precluded a finding that P&S owns a family of marks for the shared INDUSTRY element. In addition, the evidence presented by P&S was insufficient to prove that the marks were famous. The CAFC agreed with the Board’s finding of P&S’s dilution claim.

The CAFC found the Board’s findings are supported by substantial evidence, and the Board correctly found there was no likelihood of confusion of dilution.

Takeaway

- Certain portions of a mark can be determined as being dominant.

- Third party registrations are relevant in proving weakness of certain portions of a mark.

Tags: Dilution > Likelihood of Confusion under 15 U.S.C. § 1052(d) > Trademark

Making DJ Jurisdiction Easier to Maintain

| June 22, 2021

Trimble Inc. v. PerDiemCo LLC

Decided on May 12, 2021

Opinion by: Dyk, Newman, and Hughes

Summary:

How many letters, emails, and/or telephone calls from an out-of-state patent owner to an alleged patent infringer does it take to establish specific personal jurisdiction over that out-of-state patent owner in the alleged infringer’s home state? Somewhere between 3 and 22, depending on the nature of those communications.

Procedural History:

Trimble and Innovative Software Engineering (ISE) filed a lawsuit in its home state (California), seeking declaratory judgment that it doesn’t infringe out-of-state (Texas) PerDiemCo’s patents. The district court dismissed the case for lack of specific personal jurisdiction over PerDiemCo, relying on Red Wing Shoe Co. v. Hockerson-Halberstadt, Inc., 148 F.3d 1355, 1361 (Fed. Cir. 1998) (“[a] patentee should not subject itself to personal jurisdiction in a forum solely by informing a party who happens to be located there of suspected infringement” because “[g]rounding personal jurisdiction on such contacts alone would not comport with principles of fairness.”). The Federal Circuit reversed, finding specific personal jurisdiction.

Background:

PerDiemCo is a Texas LLC owning eleven geofencing patents monitoring a vehicle’s entry or exit from a preset area, electronically logging hours and activities of the vehicle’s driver. PerDiemCo’s sole owner, officer, and employee is Robert Babayi, a patent attorney living and working in Washington, DC, who rents office space in Marshall, Texas, that had never been visited.

Trimble is incorporated in Delaware and headquartered in Sunnyvale, CA. ISE is a wholly owned subsidiary LLC of Trimble, headquartered in Iowa.

Mr. Babayi sent a letter to ISE in Iowa offering a nonexclusive license and including an unfiled patent infringement complaint for the Northern District of Iowa and a claim chart detailing the alleged infringement. ISE forwarded that letter to Trimble’s Chief IP Counsel in Colorado, who was the point of contact for this matter. Mr. Babayi communicated “at least twenty-two times” by letter, email, and telephone calls with Trimble’s IP Counsel in Colorado, to negotiate and to further substantiate infringement allegations, including Trimble’s products, more patents, and more claim charts. PerDiemCo also threatened to sue in the Eastern District of Texas, identifying local counsel.

Personal Jurisdiction Primers:

- PerDiemCo’s communications with Trimble’s IP Counsel in Colorado are considered, for personal jurisdiction, purposefully directed to the company at its headquarters (in California), not to the location of counsel. See, Maxchief Investments Ltd. v. Wok & Pan, Ind., Inc., 909 F.3d 1134, 1139 (Fed. Cir. 2018).

- “[A] tribunal’s authority [to exercise personal jurisdiction over a defendant] depends on the defendant’s having such ‘contacts’ with the forum State that ‘the maintenance of the suit’ is ‘reasonable, in the context of our federal system of government,’ and ‘does not offend traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice.’” “The contacts needed for [specific] jurisdiction often go by the name ‘purposeful availment.’” Ford Motor Co. v. Mont. Eighth Jud. Dist. Ct., 141 S. Ct. 1017, 1024 (2021) (quoting Int’l Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U.S. 310, 316-317 (1945)).

- From Burger King Corp. v. Rudzewicz, 471 U.S. 462 (1985) and World-Wide Volkswagon Corp. v. Woodson, 444 U.S. 286 (1980), courts determine whether the exercise of jurisdiction would “comport with fair play and substantial justice” by considering five factors: (1) the burden on the defendant; (2) the forum State’s interest in adjudicating the dispute; (3) the plaintiff’s interest in obtaining convenient and effective relief; (4) the interstate judicial system’s interest in obtaining the most efficient resolution of controversies; and (5) the shared interest of the several States in furthering fundamental substantive social policies.

Decision:

In Red Wing, a cease-and-desist letter was deemed “more closely akin to an offer for settlement of a disputed claim rather than an arms-length negotiation in anticipation of a long-term continuing business relationship.” Accordingly, in Red Wing, this court held that “[p]rinciples of fair play and substantial justice afford a patentee sufficient latitude to inform others of its patent rights without subjecting itself to jurisdiction in a foreign forum.” However, this year’s Supreme Court Ford decision and other post-Red Wing Supreme Court decisions have emphasized that “analysis of personal jurisdiction cannot rest on special patent policies.”

Repeated communications stent into a state may create specific personal jurisdiction, depending on the nature and scope of such communications. Quill Corp. v. North Dakota, 504 U.S 298, 308 (1992). And, the out-of-state defendant’s “negotiation efforts, although accomplished through telephone and mail, can still be considered as activities ‘purposefully directed’ at residents of [the forum].” Inamed Corp. v. Kuzmak, 249 F.3d 1356, 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2001) (applying Quill). Personal jurisdiction was held to be reasonable after the out-of-state defendant sent communications to eleven banks located in the forum state identifying patents, alleging infringement, and offering non-exclusive licenses, rejecting Red Wing and its progeny as having created a rule that “the proposition that patent enforcement letters can never provide the basis for jurisdiction in a declaratory judgment action.” Jack Henry & Associates, Inc. v. Plano Encryption Technologies LLC, 910 F.3d 1199, 1201, 1206 (Fed. Cir. 2018); see also, Genetic Veterinary Sciences, Inc. v. Laboklin, GmbH & Co. KG, 933 F.3d 1302, 1312 (Fed. Cir. 2019).

Beyond the sending of communications into a forum, DJ jurisdiction can also be premised on other contacts, such as “hiring an attorney or patent agent in the forum state to prosecute a patent application that leads to the asserted patent, see Elecs. for Imaging, Inc. v. Coyle, 340 F.3d 1344, 1351 (Fed. Cir. 2003); physically entering the forum to demonstrate the technology underlying the patent to the eventual plaintiff, id., or to discuss infringement contentions with the eventual plaintiff, Xilinx, Inc. v. Papst Licensing GmbH & Co. KG, 848 F.3d 1346, 1357 (Fed. Cir. 2017); the presence of ‘an exclusive licensee … doing business in the forum state,’ Brekenridge Pharm., Inc. v. Metabolite Labs., Inc., 444 F.3d 1356, 1366-67 (Fed. Cir. 2006); and ‘extra-judicial patent enforcement’ targeting business activities in the forum state, Campbell Pet Co. v. Miale, 542 F.3d 879, 886 (Fed. Cir. 2008).”

The Supreme Court’s recent Ford decision reinforces “that a broad set of a defendant’s contacts with a forum are relevant to the minimum contacts analysis.” In Ford, personal jurisdiction could be exercised over Ford even though the two types of vehicles involved in the accident were not sold in the forum states. Specific personal jurisdiction simply “demands that the suit ‘arise out of or relate to the defendant’s contacts with the forum.’” So, the broader efforts by Ford in selling similar vehicles and having dealerships in the forum states established specific personal jurisdiction.

Unlike Red Wing, which involved a total of three letters (asserting patent infringement and offering a nonexclusive license), this case involved twenty-two communications, “an extensive number of contacts with the forum in a short period of time [three months].” And unlike Red Wing “solely…informing a party who happens to be located [in the forum state] of suspected infringement,” this case’s communications continually amplified threats of infringement, including continually adding more patents, more products, suggesting mediation to reach a settlement on infringement allegations, and threat of suit in EDTx, identifying counsel that PerDiemCo planned to use. As such, “PerDiemCo’s attempts to extract a license in this case are much more akin to ‘an arms-length negotiation in anticipation of a long-term continuing business relationship’ over which a district court may exercise jurisdiction.”

As for whether specific personal jurisdiction would comport with fair play and substantial justice, the court found no fairness concerns as follows:

- Burden on the defendant: PerDiemCo’s office in Texas is “pretextual” (not an operating company, but merely an IP portfolio owner, with no employees in Texas) and is far from Washington, DC where Mr. Babayi lives and works. So, if Texas is ok, so is California.

- Forum state’s interest in adjudicating the dispute: ND Cal. has significant interest since Trimble is a resident there.

- Plaintiff’s interest in obtaining convenient and effective relief: Trimble is near the federal district court.

- Interstate judicial system’s interest in obtaining the most efficient resolution of controversies: no favor either way.

- The shared interest of the several states in furthering fundamental substantive social polices: not applicable.

Takeaways:

- This case is a good refresher for specific personal jurisdiction in the DJ action arena for patent owners and accused infringers.

- Red Wing is NOT overturned. Quite the contrary, the court quotes from the Supreme Court’s recent Ford decision that treats “isolated or sporadic [contacts] differently from continuous ones,” and confirms that “Red Wing remains correctly decided with respect to the limited number of communications involved in that case.” The court only emphasizes that “there is no general rule that demand letters can never create specific personal jurisdiction.”

- In Red Wing, the patentee’s first letter asserted patent infringement and offered a nonexclusive license. The second letter granted an extension of time for a response and asserted more products as infringing the patent. The third letter rebutted Red Wing’s noninfringement analysis and continued to offer to negotiate a nonexclusive license. So, there was some “amplification” in the second letter, just like in this case. But, the continued back and forth negotiations in Red Wing was much more limited than in this case. Where do we cross the Red Wing threshold and enter into specific personal jurisdiction for a DJ action? It is not as simple as somewhere between 3 and 22. It is the nature of the communications – the continuing of negotiations “to extract a license” that likens the behavior/communications to “an arms-length negotiation in anticipation of a long-term continuing business relationship.”

- From this case, patent owners must be careful to avoid continued communications, whether by letter, email, or telephone, that as a whole can be construed to be a continuation of negotiations to extract a license or “an arms-length negotiation in anticipation of a long-term continuing business relationship.” If the desired nonexclusive license doesn’t look promising after just a handful of contacts, this case suggests that it is safer for the patent owner to hold off further back and forth negotiations and file a complaint in the patent owner’s preferred forum state, otherwise risk a DJ action in the accused infringer’s home court. For the accused infringer, this case suggests that stringing the patent owner out and creating more back and forth communications would help secure specific personal jurisdiction for a DJ action in the accused infringer’s home court.

Lying in a Deposition – Never a Good Policy

| June 2, 2021

Cap Export, LLC v. Zinus, Inc.

Decided on May 5, 2021

Summary

Rule 60(b)(3) relieves a patent challenger of a final judgment entered in favor of a patentee where the patent challenger with due diligence could not discover a later-revealed fraud committed by the patentee during the underlying litigation in which the deposed patentee’s witness lied to conceal his knowledge of on-sale prior art determined to be highly material to the validity of the patent.

Details

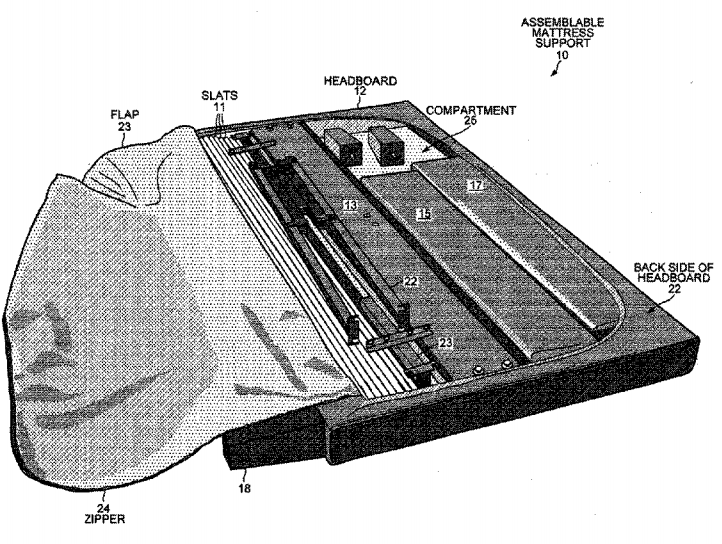

Zinus owns U.S. Patent No. 8,931,123 (“the ’123 patent”) entitled “Assemblable mattress support whose components fit inside the headboard.” The invention allows for packing various components of a bed into its headboard compartment for easy shipping in a compact state. The concept may be seen in one of the ‘123 patent figures:

The application that resulted in the ‘123 patent was filed in September 2013.

In 2016, Cap Export, LLC (“Cap Export”) sought declaratory judgment of invalidity and noninfringement of the ‘123 patent in the Central District of California. The lawsuit eventually resulted in the district court upholding the validity of the ‘123 patent claims as not anticipated or obvious over all prior art references considered. The final judgment stipulated and entered in favor of Zinus included payment of $1.1 million in damages to Zinus, and a permanent injunction against Cap Export[1]. Particularly relevant to the present case is the fact that in the course of the lawsuit, Cap Export deposed Colin Lawrie, Zinus’s president and expert witness, as to his knowledge of various prior art items.

In 2019, Zinus sued another company for infringement of the ‘123 patent. This second lawsuit prompted Cap Export to learn that Zinus’s group company had bought hundreds of beds manufactured by a foreign company which apparently had a bed-in-a-headboard feature, before the filing date of the ‘123 patent. Colin Lawrie, the aforementioned Zinus’s president, appears to be involved in this transaction as the purchase invoice was signed by Lawrie himself.

Cap Export then timely filed a Rule 60(b)(3) motion for relief from the final judgment, alleging that Lawrie during the previous deposition lied to Cap Export’s counsel. Some questions and answers highlighted in the case include:

Q. Prior to September 2013 had you ever seen a bed that was shipped disassembled in one box?

A. No.

Q. Not even—I’m not talking about everything stored in the headboard, I’m just saying one box.

A. No, I don’t think I have.

In the Rule 60(b)(3) proceeding, Lawrie admitted that his deposition testimony was “literally incorrect” while denying intentional falsity because he had misunderstood the question to refer to a bed contained “in one box with all of the components in the headboard,” rather than a bed contained “in one box” (where most laypersons should know of the latter, if not the former).

The district court was not convinced, pointing to the fact that Cap Export’s counsel had rephrased the question to distinguish the two concepts. Also, emails were discovered showing repeated sales of the beds at issue to Zinus’s family companies, the record which Zinus admitted had been in its possession throughout the underlying litigation.

The district court set aside the final judgement under Rule 60(b)(3), finding that the purchased beds were “functionally identical in design” to the ’123 patent claims, and that Lawrie’s repeated denials of his knowledge of such beds amounted to affirmative misrepresentations. Zinus appealed.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed.

FRCP Rule 60(b)(3)

Rule 60(b)(3) relieves a losing party of a final judgment where an opposing party commits “fraud … , misrepresentation, or misconduct.” The Ninth Circuit applies an additional requirement that the fraud not be discoverable through “due diligence”[2]. A movant must prove by clear and convincing evidence that the opposing party has obtained the verdict in its favor through fraudulent conduct which “prevented the losing party from fully and fairly presenting the defense.” Since the issue is procedural, the Federal Circuit follows regional circuit law and reviews the district court decision for abuse of discretion.

Due Diligence in Discovering Fraud

Zinus’s main contention was that the due diligence requirement is not satisfied, arguing that the key evidence would have been discovered had Cap Export’s counsel taken more rigorous discovery measures[3] specific to patent litigation.

The Federal Circuit disagreed, finding that due diligence in discovering fraud is not about the lawyers’ lacking a requisite standard of care, but rather, the question is “whether a reasonable company in Cap Export’s position should have had reason to suspect the fraud … and, if so, took reasonable steps to investigate the fraud.”

Here, Cap Export met the requirement because there was no reason to suspect the fraud in the first place. Lawrie’s repeated denials in the deposition testimony, combined with the impossibility to reach the concealed evidence despite numerous search efforts by Cap Export and the general unavailability of such evidence, forestalled an initial suspicion of fraud which would otherwise call for further inquiry into the possible misconduct.

Opponent’s Fraud Preventing Fair and Full Defense

The Federal Circuit also found that the district court had not abuse its discretion in judging other parts of Rule 60(b)(3) jurisprudence.