Broadcom Wi-Fi chips, and Apple smartphones, tablets and computers held responsible for patent infringements

| March 18, 2022

California Institute of Technology v. Broadcom Ltd.

Decided on February 4, 2022

Lourie, Linn (Senior), and Dyk. Court opinion by Linn. Concurring-in-part-and-dissenting-in-part Opinion by Dyk.

Summary

On appeals from the district court for the judgment of infringement of patents in favor of Caltech, the patentee, against Broadcom totaling $288,246,156, and against Apple totaling $885,441,828 and denial of JMOL on infringement thereof, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s denial of the JMOL because the Court was not persuaded that the district court erred in construing the term “repeat” in the claim of the patent in issue, and that the record before the jury permits only a verdict of no infringement. Judge Dyk filed a dissenting opinion regarding the denial of JMOL on infringement.

Details

I. Background

The California Institute of Technology (“Caltech”) filed an infringement suit against Broadcom Limited, Broadcom Corporation, and Avago Technologies Ltd. (collectively “Broadcom”) and Apple Inc. (“Apple”) at the District Court for the Central District of California (“the district court”). Caltech alleged infringement of its U.S. Patents No. 7,116,710 (“the ’710 patent”), No. 7,421,032 (“the ’032 patent”), and No. 7,916,781 (“the ’781 patent”) by certain Broadcom Wi- Fi chips and Apple products incorporating those chips, including smartphones, tablets, and computers. The accused Broadcom chips were developed and supplied to Apple pursuant to Master Development and Supply Agreements negotiated and entered into in the United States.

While the case involves several issues regarding these patents, this case review focuses on the issue of claim construction regarding the term “repeat” in the ’710 patent.

Caltech argued that the accused chips infringed claims 20 and 22 of the ’710 patent. Claims 20 and 22 of the ’710 patent depend from claim 15, which provides:

15. A coder comprising: a first coder having an input configured to receive a stream of bits, said first coder operative to repeat said stream of bits irregularly and scramble the repeated bits; and a second coder operative to further encode bits output from the first coder at a rate within 10% of one. (emphasis added)

Caltech specifically identified as infringing products two encoders contained in the Broadcom chips- a Richardson-Urbanke (“RU”) encoder and a low-area (“LA”) encoder. In the accused encoders, incoming information bits are provided to AND gates in the RU encoder or multiplexers in the LA encoder.

In its brief , Broadcom presents the following table, using the example of the functioning of a single AND gate, to show how outputs are determined by the two inputs:

| Input 1 (Information Bit) | Input 2 (Parity-Check Bit) | AND Gate Output |

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

For each AND gate, the output of the gate is 1 if both inputs (the information bit and the parity-check bit) are l ; otherwise, the output is 0. One consequence of this logic is that if the parity-check bit is 1 (as shown in rows two and four), then the output is identical to the information-bit input. If the parity-check bit is 0, the output is 0, 1regardless of the value of the input (rows one and three).

For the claim construction regarding the term “repeat” in the ’710 patent, Caltech advocated for the term’s plain and ordinary meaning. In contrast, Apple and Broadcom proposed a narrower construction, contending that “repeat” should be construed as “creating a new bit that corresponds to the value of an original bit (i.e., a new copy) by storing the new copied bit in memory. A reuse of a bit is not a repeat of a bit.” (emphasis added)

In pre-trial, at the conclusion of the Markman hearing, the district court construed the term “repeat” to have its plain and ordinary meaning and noted that the repeated bits “are a construct distinct from the original bits from which they are created,” but that they need not be generated by storing new copied bits in memory.

During trial, the district court instructed the jury that the term “repeat” means “generation of additional bits, where generation can include, for example, duplication or reuse of bits.” (emphasis added) Apple and Broadcom then argued that the chips did not infringe the ’710 patent because they did not repeat information bits at all, much less irregularly. The jury ultimately found infringement of all the asserted claims. Broadcom and Apple filed post-trial motions for JMOL and a new trial, challenging the jury’s infringement verdict. The district court denied JMOL, finding no error in its claim construction ruling and concluding that the verdict was supported by substantial evidence.

The district court entered judgment against Broadcom totaling $288,246,156, and against Apple totaling $885,441,828. These awards included pre-judgment interest, as well as post-judgment interest and an ongoing royalty at the rate set by the jury’s verdict.

Broadcom and Apple appealed.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit (“the Court”) affirmed the district court’s construction of the term “repeat” and JMOL on Infringement.

1. Claim Construction of “repeat”

Broadcom and Apple argued that the district court erroneously construed the term “repeat,” contending that the accused AND gates and multiplexers do not “repeat” information bits in the manner claimed, but instead combine the information bits with bits from a parity-check matrix to output new bits reflecting that combination. Broadcom and Apple further argue that the AND gates and multiplexers also do not generate bits “irregularly,” asserting that they output the same number of bits for every information bit.

The Court was not persuaded. The Court stated that the district court correctly observed that the claims require repeating but do not specify how the repeating is to occur: “The claims simply require bits to be repeated, without limiting how specifically the duplicate bits are created or stored in the memory.” (emphasis added) The Court further stated that the specifications confirm that construction and describe two embodiments, neither of which require duplication of bits.

2. JMOL on Infringement

Broadcom and Apple argued that, looking at each gate alone and the “repeat” requirement, AND gate does not “repeat” the inputted information bit “because the AND gate’s output depends on not only the information bit but also the parity-check-matrix bit.”

In contrast, Caltech argued that, considering the system as a whole, each information bit is in fact repeated, and they are not all repeated the same number of times. To support Caltech’s position, Caltech’s expert, Dr. Matthew Shoemake explained that in the parity-check-bit-equals-1 situation (second and fourth rows of the table), the output bit is a “repeat” of the information- bit input. Where the parity-check bit is 1, the gate affirmatively enables the information bit to be duplicated as the output bit. That is a ‘repeat’ … because the information bit in that situation ‘flows through’ to appear again in the output.”

The Court sided Caltech, and affirmed the district court’s denial of JMOL.

III. Concurring-in-part-and-dissenting-in-part Opinion

Judge Dyk disagreed with the majority’s holding that substantial evidence supports the jury’s verdict of infringement of the asserted claims of the ’710 patent (and the ’032 patent) and stated that he would reverse the district court’s denial of JMOL of no literal infringement.

Given that the district court constructed the term “repeat” to mean “generation of additional bits, where generation can include, for example, duplication or reuse of bits,” Judge Dyk located the critical question to be whether there is substantial evidence that the accused devices cause “generation of additional bits.” Judge Dyk then pointed out that the problem for Caltech (and for the majority) is that Caltech never established that the accused devices generate “additional bits,” as required by the district court’s claim construction.

The infringement theory presented at trial explained that the accused devices work as follows: information bits are input into the accused devices, those bits travel down branched wires to the inputs of 972 AND gates, and three to twelve of those AND gates will be open for each information bit, thus outputting the bits a different number of times. In Judge Dyk’s view, for this theory to satisfy Caltech’s burden, Caltech was required to establish where, when, and how additional bits were generated. Judge Dyk stated the record does not support a theory that the branched wires generate additional bits.

Winning on Objective Indicia of Non-Obviousness in an IPR

| March 11, 2022

Quanergy Systems, Inc.. v. Velodyne Lidar USA, Inc.

Opinion by: O’Malley, Newman, and Lourie

Decided on February 4, 2022

Summary:

The Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s validity decisions in two IPRs for Velodyne’s patent on lidar, relying substantially on Velodyne’s objective evidence of non-obviousness. Quanergy’s appeal attacked the PTAB’s presumption of a nexus between Velodyne’s product and the claimed invention. In particular, Quanergy challenged the nexus presumption by arguing that there were unclaimed features that attributed to the significance of Velodyne’s products, instead of the claimed invention. The Federal Circuit found the PTAB’s reasoning for how each alleged unclaimed feature resulted directly from claim limitations – such that Velodyne’s products are essentially the claimed invention – were found to be both adequate and reasonable.

Procedural History:

Quanergy Systems, Inc. (Quanergy) challenged the validity of Velodyne Lidar USA, Inc. (Velodyne) U.S. Patent 7,969,558 in two inter partes review (IPR) proceedings before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) as being obvious. The PTAB sustained the validity of the ‘558 patent. The Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s decision.

Background:

The ‘558 patent relates to a lidar-based 3-D point cloud measuring system, useful in autonomous vehicles. “Lidar” is an acronym for “Laser Imaging Detection and Ranging.” Lidar technology uses a pulse of light to measure distance to objects. Each pulse of light for measurement results in one “pixel” and a collection of pixels is called a “point cloud.” A 3-D point cloud may be achieved by making measurements with the light pulses in up-down directions, as well as in 360 degrees. Representative claim 1 is as follows:

A lidar-based 3-D point cloud system comprising:

a support structure;

a plurality of laser emitters supported by the support structure;

a plurality of avalanche photodiode detectors supported by the support structure; and

a rotary component configured to rotate the plurality of laser emitters and the plurality of avalanche photodiode detectors at a speed of at least 200 RPM.

Quanergy relied on a Mizuno reference that uses a “triangulation system” measuring the distance to an object by detecting light reflected from the object to image sensors. Quanergy also relied on a Berkovic reference that teaches the triangulation technique, as well as a time-of-flight sensing technique. To win on obviousness, Quanergy relied on a broad interpretation of “lidar” to encompass both triangulation systems and “pulsed time-of-flight (ToF) lidar.”

However, the PTAB construed “lidar” to mean pulsed time-of-flight lidar because the ‘558 specification exclusively focuses on pulsed time-of-flight lidar in which distance is measured by the “time” of travel (i.e., flight) of the laser pulse to and from an object. The PTAB also found that Mizuno does not address a time-of-flight lidar system. Instead, Mizuno’s triangulation system is a short-range measuring device. And, the PTAB held that the skilled artisan would not have had a reasonable expectation of success in modifying Mizuno’s device to use pulsed time-of-flight lidar because Quanergy’s expert did not explain how or why a skilled artisan would have had an expectation of success in overcoming the problems in implementing a pulsed time-of-flight sensor in a short range measurement system such as that of Mizuno’s. Indeed, the Berkovic reference was found to suggest that the accuracy of pulsed time-of-flight lidar measurements degrades in shorter ranges, such as in Mizuno’s system.

But, more importantly, the PTAB relied substantially on Velodyne’s objective evidence of non-obviousness, which “clearly outweighs any presumed showing of obviousness by Quanergy” even if Quanergy satisfied obviousness with respect to the first three of the four Graham v John Deere factors (i.e., (1) scope and content of the prior art, (2) difference between the prior art and the claims at issue, (3) level of ordinary skill in the pertinent art, and (4) any objective indicia of nonobviousness).

Decision:

As for the initial claim construction issue regarding “lidar,” the Federal Circuit agreed with the strength of the intrinsic record focusing exclusively on pulsed time-of-flight lidar, collecting time-of-flight measurements, and taking note of the specification’s boasted ability to “collect approximately 1 million time of flight (ToF) distance points per second, overcoming commercial point cloud systems inability to meet the demands of autonomous vehicle navigation. Indeed, the court found Quanergy’s arguments for a broader construction to be inconsistent with the specification and therefore unreasonable.

Quanergy also challenged the PTAB’s presumption of a nexus between the claimed invention and Velodyne’s evidence of an unresolved long-felt need, industry praise, and commercial success.

To accord substantial weight to Velodyne’s objective evidence, that evidence must have a “nexus” to the claims, i.e., there must be a “legally and factually sufficient connection” between the evidence and the patented invention.

The Federal Circuit may presume a nexus to exist “when the patentee shows that the asserted objective evidence is tied to a specific product and that product ‘embodies the claimed features, and is co-extensive with them.” This co-extensiveness does not require a patentee to prove perfect correspondence between the product and the patent claim. Instead, it is sufficient to demonstrate that “the product is essentially the claimed invention.” In this analysis, “the fact finder must consider the unclaimed features of the stated products to determine their level of significance and their impact on the correspondence between the claim and the products.” “Some unclaimed features ‘amount to nothing more than additional insignificant features,’ such that presuming nexus is still appropriate.” “Other unclaimed features, like a ‘critical’ unclaimed feature that is claimed by a different patent and that materially impacts the product’s functionality, indicate that the claim is not coextensive with the product.”

This presumption of a nexus is rebuttable. However, a patent challenger may not rebut the presumption of nexus with argument alone. The patent challenger may present evidence showing that the proffered objective evidence was “due to extraneous factors other than the patented invention” such as unclaimed features or external factors like improvements in marketing or superior workmanship.

Here, Quanergy argued that the PTAB failed to consider the issue of unclaimed features before presuming a nexus and failed to provide an adequate factual basis or reasoned explanation dismissing the unclaimed features argument. Quanergy argued that Velodyne’s evidence relies on unclaimed features, including high frame-rate, dense 3D point cloud with a wide field of view and collecting measurements in an outward facing lidar for 360 degree azimuth and 26 degree vertical arc. And, such unclaimed features are critical and materially impact the functionality of Velodyne’s products. Therefore, the requisite presumption of a nexus does not exist.

However, the court found that the PTAB considered, and adequately/reasonably did so, the unclaimed features arguments, reasonably finding that Veloydyne’s products embody the full scope of the claimed invention and that the claimed invention is not merely a subcomponent of those products. First, the PTAB credited Velodyne’s expert testimony providing a detailed analysis mapping claim 1 to description of Velodyne’s product literature. Second, the claims call for a 3-D point cloud and the density of the cloud and the 360 degree horizontal field of view (i.e., the ”unclaimed features”) “result directly” from the limitation for “[rotating] the plurality of laser emitters and the plurality of avalanche photodiode detectors at a speed of at least 200 RPM.” The “3-D” feature necessarily infers both horizontal and vertical fields of view. The PTAB also pointed to (1) contemporaneous news articles describing the long-felt need for a lidar sensor that could capture points rapidly in all directions and produce a sufficiently dense 3-D point cloud for autonomous navigation, (2) articles praising Velodyne as the top lidar producer and Velodyne’s products, and (3) financial information and articles reflecting Velodyne’s revenue and market share to show commercial success.

The court also found the PTAB’s analysis of those unclaimed features arguments to be commensurate with Quanergy’s presentation of the issue. Here, the court found Quanergy’s unclaimed features arguments to be merely skeletal, undeveloped arguments. In contrast, the PTAB’s explanation of how each alleged unclaimed feature results directly from claim limitations – such that Velodyne’s products are essentially the claimed invention – were found to be both adequate and reasonable.

Quanergy also presented new arguments (not previously presented to the PTAB) that, to obtain the dense 3-D point cloud, Velodyne’s products require the unclaimed critical features of (1) more than 2 laser emitters, (2) a high pulse rate, (3) vertical angular separation between pairs of emitters and detectors, and (4) a rotation speed significantly greater than 200 RPM. However, the court held that these new arguments, presented only on appeal, were forfeited.

Takeaways:

- This case is a good primer for how to best present or attack objective indicia of non-obviousness.

- One key to success for objective indicia of non-obviousness is expert testimony mapping claimed features to product literature and explaining how and why that description of the product is essentially the claimed invention. Other helpful evidence includes contemporaneous news articles about the long-felt need, praise for the subject product, and financial information/articles showing the company’s commercial success, presumably tied to the subject product.

- If unclaimed features are asserted to attack a presumption of nexus, expert testimony explaining how those alleged unclaimed features are direct results from claimed limitations, so as to side step the attack, is helpful.

- Skeletal arguments are insufficient. If making an unclaimed features argument, it is best to flesh it out before the PTAB in detail, otherwise it will be considered forfeited if newly presented on appeal.

CLAIMS ARE VIEWED AND UNDERSTOOD IN THE CONTEXT OF THE SPECIFICATION AND THE PROSECUTION HISTORY

| March 7, 2022

Nature Simulation Systems Inc., v. Autodesk, Inc.

Before NEWMAN, LOURIE, and DYK, Circuit Judges. Opinion for the court filed by Circuit Judge NEWMAN. Dissenting opinion filed by Circuit Judge DYK.

Summary

The Federal Circuit ruled in a split decision that the United States District Court for the Northern District of California erred in invalidating Nature Simulation System’s patents as indefinite.

Background

NSS sued Autodesk for allegedly infringing US Patents No. 10,120,961 (“the ’961 patent”) and No. 10,109,105 (“the ’105 patent”). The ’961 patent is a continuation-in-part of the ’105 patent, and both are entitled “Method for Immediate Boolean Operations Using Geometric Facets” directed to a computer-implemented method for building three-dimensional geometric objects using boolean operation.

The district court held a claim construction (Markman) hearing and subsequently ruled the claims invalid on the ground of claim indefiniteness, 35 U.S.C. § 112(b). In the hearing, Autodesk presented an expert declaration to request the construction of eight claim terms. NSS argued that construction is not necessary and the challenged terms should receive their ordinary meaning in the field of technology. The district court did not construe the terms. The district court explained that a claim term is indefinite, as a matter of law, if there are any “unanswered questions” about the term. The decision of the district court was based on two of the challenged terms in clauses [2] and [3] of Claim 1:

1. A method that performs immediate Boolean operations using geometric facets of geometric objects

implemented in a computer system and operating with a computer, the method comprising:

[1] mapping rendering facets to extended triangles that contain neighbors;

[2] building intersection lines starting with and ending with searching for the first pair of triangles that hold a start point of an intersection line by detecting whether two minimum bounding boxes overlap and performing edge-triangle intersection calculations for locating an intersection point, then searching neighboring triangles of the last triangle pair that holds the last intersection point to extend the intersection line until the first intersection point is identical to the last intersection point of the intersection line ensuring that the intersection line gets closed or until all triangles are traversed;

[3] splitting each triangle through which an intersection line passes using modified Watson method, wherein the modified Watson method includes removing duplicate intersection points, identifying positions of end intersection points, and splitting portion of each triangle including an upper portion, a lower portion, and a middle portion;

[4] checking each triangle whether it is obscure or visible for Boolean operations or for surface trimming;

[5] regrouping facets in separate steps that includes copying triangles, deleting triangles, reversing the normal of each triangle of a geometric object, and merging reserved triangles to form one or more new extended triangle sets; and

[6] mapping extended triangles to rendering facets.

The two terms are “searching neighboring triangles of the last triangle pair that holds the last intersection point” and “modified Watson method.” The district court stated that even if the questions are answered in the specification, the definiteness requirement is not met if the questions are not answered in the claims. NSS argued that on the correct law the claims are not indefinite.

Discussion

The Federal Circuit cited the opinion in Nautilus and emphasized that the claims are viewed and understood in the context of the specification and the prosecution history, as the Court summarized in Nautilus (Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc., 572 U.S. 898, 909 (2014) ).

The district court held the claims indefinite based on the “unanswered questions” that were suggested by Autodesk’s expert, as stated in the Declaration:

¶ 27. [T]he claim language, standing alone, does not specify which of those neighboring, intersecting triangles should be used to identify additional intersection points. Nor does the claim specify (where there are multiple potential intersection points for a given pair of neighboring triangles) which of the multiple potential intersection points should be used to extend the intersection line. Thus, the claim language is indefinite.

The Federal Circuit states that the “unanswered questions” is an incorrect standard and specifically pointed out that “ ‘Claim language, standing alone’ is not the correct standard of law, and is contrary to uniform precedent.” The Federal Circuit found that the district court did not consider the information in the specification that was not included in the claims and the district court misperceived the function of patent claims.

The Federal Circuit also noted that the court did not discuss the Examiner’s Amendment. During the prosecution of the ‘961 patent, the examiner discussed with the inventor and later suggested an amendment in the Notice Of Allowance to clarify the disputed language. The examiner suggested amending claim 1 and then withdrew the rejection based on the amendment. The amendment includes the limitation of the term in clause [3] as follows:

[3] splitting each triangle through which an intersection line passes using modified Watson method, wherein the modified Watson method includes removing duplicate intersection points, identifying positions of end intersection points, and splitting portion of each triangle including an upper portion, a lower portion, and a middle portion;

The Federal Circuit noted that the district court did not discuss the Examiner’s Amendment and held that the claims are invalid since the questions raised by Autodesk’s expert were not answered. The Federal Circuit found that the district court fails to give proper weight to the prosecution history showing the resolution of indefiniteness by adding the designated technologic limitations to the claims. The Federal Circuit further explained that “[a]ctions by PTO examiners are entitled to appropriate deference as official agency actions, for the examiners are deemed to be experienced in the relevant technology as well as the statutory requirements for patentability.” The Federal Circuit stated that “[i]t is not disputed that the specification describes and enables practice of the claimed method, including the best mode. The claims, as amended during prosecution, were held by the examiner to distinguish the claimed method from the prior art and to define the scope of the patented subject matter.”

Judge Dyk dissented from the majority and opined that the district court had read the patent claims in light of the specification to determine if it would inform those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention with reasonable certainty, which is exactly what is required under Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc., 572 U.S. 898, 910 (2014). Judge Dyk also states that the majority simply does not address the problem that the limitations are “not describe[d]” in the patent, “ambiguous” and “unclear,” and “inconsistent with” Figure 13 and the accompanying text. In his view, the test for definiteness is whether the claims “inform those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention with reasonable certainty,” but the majority relied on the fact that these limitations were suggested by the patent examiner.

Takeaway

- Claims are viewed and understood in the context of the specification and the prosecution history.

- Patent claims must provide sufficient clarity to inform about the scope of the invention with reasonable certainty.

BREATHE EASIER, THE CAFC PROVIDES GUIDANCE ON CONSTRUING THE CLAIMED CONCENTRATION OF A STABILIZER IN PATENTS FOR AN ASTHMA DRUG

| February 25, 2022

AstraZeneca v. Mylan Pharmaceuticals

Decided December 8, 2021

Taranto, Hughes, and Stoll. Opinion by Stoll. Dissent by Taranto

Summary:

AstraZeneca sued Mylan for infringement of its patents covering Symbicort pressurized metered-dose inhaler (pMDI) which is used for treating asthma. At issue in this case is how to construe the limitation “PVP K25 is present at a concentration of 0.001% w/w.” The district court construed the concentration using the ordinary standard scientific convention using only one significant figure to encompass the range from 0.0005% to 0.0014%. Based on this construction, Mylan stipulated to infringement. The district court then held a trial on validity and upheld the validity of the asserted claims. The CAFC affirmed the district court’s judgment of validity. But the CAFC disagreed with the construction of the concentration limitation. The CAFC held that the construction of the term should be narrower than the range provided by the ordinary meaning due to disclosures in the specification and arguments and amendments in the prosecution history. The CAFC construed the noted concentration of 0.001% to include the narrower range of 0.00095% to 0.00104%. Thus, the CAFC vacated the judgment of infringement and remanded for further proceedings on infringement.

Details:

The patents at issue in this case are U.S. Patent Nos. 7,759,328; 8,143,239; and 8,575,137 which cover the asthma inhaler Symbicort pMDI. A pMDI inhaler uses a propellant gas that is in liquid form under pressure in the pMDI device. When the inhaler is activated, the propellant causes the gas to come out as a spray making it easier to deliver the medication to the lower lungs. The representative claim is provided:

13. A pharmaceutical composition comprising

formoterol fumarate dihydrate, budesonide, HFA227, PVP K25, and PEG-1000,

wherein the formoterol fumarate dihydrate is present at a concentration of 0.09 mg/ml,

the budesonide is present at a concentration of 2 mg/ml,

the PVP K25 is present at a concentration of 0.001% w/w, and

the PEG-1000 is present at a concentration of 0.3% w/w.

Mylan appealed the district court’s stipulated judgment of infringement asserting that the district court erred in the construction of the concentration of PVP K25 of 0.001%. Mylan also appealed the district court judgement of nonobviousness.

The CAFC stated that as a matter of standard scientific convention, the noted concentration of 0.001% being expressed with only one significant digit would ordinarily encompass a range from 0.0005% to 0.0014%. AstraZeneca argued that this ordinary meaning controls absent lexicography or disclaimer. However, the CAFC stated that this is an acontextual construction that does not consider disclosures in the specification and arguments/amendments in the prosecution history. The CAFC stated that “[c]onsistent with Phillips, therefore, we must read the claims in view of both the written description and prosecution history.”

The CAFC stated that the testing evidence in the specification and prosecution history demonstrates that minor differences as small as ten thousandths of a percentage (four decimal places) in the concentration of PVP impact stability. The specification repeatedly describes formulations containing 0.001% PVP as providing the best suspension stability. This is also demonstrated in the data provided in the specification. The data includes formulations including PVP at concentrations of 0.0001%, 0.0005%, 0.001%, 0.01%, 0.03%, and 0.05%. The results show that the formulation containing 0.001% PVP was the most stable and that the formulation containing 0.0005% was one of the least stable formulations. The CAFC concluded that this data shows that PVP concentration of 0.001% is more stable than formulations with slight differences in PVP concentration (e.g., a concentration of 0.0005%, and that differences down to the ten-thousandth of a percentage (fourth decimal place) matters for stability.

In the prosecution history, the Applicant amended the claims to change ranges of the concentration to recite the exact concentration of PVP to 0.001% without using the qualifier “about,” and emphasized that 0.001% was critical to stability. The CAFC also stated that Applicant knew how to claim ranges and describe numbers with approximation using the term “about,” but the Applicant chose to claim the exact value. The CAFC concluded that this supports construing 0.001% narrowly, but that there should be some room for experimental error in the PVP concentration. The CAFC stated that the margin of error that is best supported by the intrinsic record is variations in the PVP concentration at the fourth decimal place (0.000095% to 0.000104%).

AstraZeneca argued that Mylan’s proposed construction is an attempt to limit the scope of the claims to the preferred embodiment. However, the CAFC stated that AstraZeneca’s proposed construction would read on two distinct formulations described in the specification (0.0005% PVP and 0.001% PVP), but the Applicant chose to claim only one of these formulations. The CAFC also stated that Applicant cancelled claims that included the 0.0005% PVP concentration and that this provides evidence that the formulations containing 0.0005% PVP are not within the scope of an asserted claim.

Regarding the nonobviousness determination by the district court, Mylan argued that the district court erred in finding that the prior art reference Rogueda taught away from the claimed invention. The CAFC citing Meiresonne v. Google, Inc., 849 F.3d 1379 (Fed Cir. 2017), stated that “a prior art reference is said to teach away from the claimed invention if a skilled artisan ‘upon reading the reference, would be discouraged from following the path set out in the reference, or would be led in a direction divergent from the path that was taken’ in the claim.”

The Rogueda reference included control formulations to compare with its novel formulations. Mylan relied on some of the control formulations as rendering the claims obvious. Rogueda disclosed that the novel formulations provided a “drastic” reduction in the amount of drug adhesion compared to the controls.

Mylan, citing Meiresonne, argued that the court’s precedent regarding “teaching away” is that a reference “that merely expresses a general preference for an alternative invention but does not criticize, discredit, or otherwise discourage investigation into the claimed invention does not teach away.” Mylan argued that Rogueda merely expresses a preference for the novel formulations over the control formulations citing a statement in the district court opinion that “Rogueda did not necessarily disparage the formulations in Controls 3 and 9.” However, AstraZeneca provided expert testimony stating that a skilled artisan looking at the adhesion results in Rogueda would conclude that the control formulations “were not suitable” and “clearly don’t work.” The district court credited the expert testimony that a skilled artisan would have known that the control formulations were unsuitable, and thus, discouraging investigation into these formulations, and concluded that Rogueda teaches away and does not render the claims obvious. The CAFC stated that there was no clear error in the district court’s determination and affirmed the validity of the claims.

Dissent

Judge Taranto dissented from the claim construction opinion. Judge Taranto stated that 0.001% should be construed to have its significant-figure meaning of 0.0005% to 0.0014% with the possibility of shrinking the lower end of the range to exclude the overlap area between the significant-figure interval of 0.001% (0.0005% to 0.0014%) and the significant-figure interval of 0.0005% (00045% to 0.00054%). Thus, if this exclusion is applied, the range would be 0.00055% to 0.0014%.

Judge Taranto takes the position that nothing in the specification or prosecution history warrants departing from the ordinary meaning. Judge Taranto pointed out that the specification, when referring to the formulations that were tested, states that several of the formulations were “considered excellent” and that the formulation with 0.001% PVP “gave the best suspension ability overall.” In the prosecution history, the Examiner stated the need for the Applicant to show criticality by showing unexpected results of a 0.001% concentration level compared to concentration levels “slightly greater or less” than 0.001% PVP. But it is unclear if the Examiner meant to include 0.0005% and other tested concentration levels tested within the meaning of “slightly greater or less.” The Examiner’s statement about criticality does not exclude 0.0005%.

Judge Taranto also stated that changing “0.001%” having one significant figure to “0.0010%” having two significant figures (as proposed by Mylan and adopted by the majority) requires rewriting the claim term, and that this rewriting is counter to the specification and prosecution history. The specification and prosecution history uniformly used only one significant figure when referring to PVP concentration. Just because four decimal places were used for some PVP concentrations does not mean that all concentration values should be read to express a degree of precision to four decimal places. The specification uses four decimal places to refer to the absolute concentration level in examples where this is unavoidable such as for 0.0001% and 0.0005%. However, absolute levels and degrees of precision are distinct.

Judge Taranto also addressed the fact that the range implied by 0.001% overlaps the range implied by 0.0005%. Judge Taranto stated that the overlap does not support adding an extra significant digit. Judge Taranto stated that “the most this overlap could possibly support would be an exclusion of the small range with the one significant-figure interval for which there is overlap resulting in the range of 0.00055% to 0.0014%. However, Judge Taranto pointed out that Mylan’s product is still within this narrower range, and thus, it is not necessary to decide whether the overlap-area exclusion is justified as a claim construction.

Comments

The majority appears to have been swayed by the fact that a formulation within the range of the ordinary meaning of the claimed concentration provided significantly different results. What is not clear is whether these different results, while not the best, could still be considered good. Judge Taranto pointed out that the specification stated that several of the tested formulations were considered excellent while the 0.001% was the best. When drafting and prosecuting patent applications, you need to be aware that your experimental data and amendments to the claims can be used to narrow the range afforded by the ordinary meaning of a certain value.

With regard to arguing non-obviousness due to a teaching away in the prior art, expert testimony can be critical and should be used to support your argument whether you are defending the validity of a patent or trying to invalidate.

REASONABLE-EXPECTATION-OF-SUCCESS REQUIREMENT CANNOT BE SATISFIED WHEN THERE IS NO EXPECTATION OF SUCCESS

| February 4, 2022

Teva Pharmaceuticals USA v. Corcept Therapeutics, Inc.

Decided December 7, 2021

Moore, Newman and Reyna (Opinion by Moore)

This precedential opinion illustrates the importance of preparing your expert for deposition. Although an expert declaration was effective in having a Post Grant Review instituted on claims 1-13 of U.S. Patent No. 10,195,214, the expert’s post-institution deposition testimony was instrumental in upholding the validity of the claims. This opinion not only addresses obviousness with respect to the reasonable expectation of success requirement, but also obviousness of ranges, a topic covered by Michael Caridi earlier this month in Indivior UK Ltd., v. Dr. Reddy’s Labs S.A., Dr. Reddy’s Labs, Inc.

Mifepristone was developed as an anti-progestin in the 1980s and was later discovered to likely inhibit the effect of cortisol on tissues, suggesting that it could be used to treat Cushing’s syndrome (a disease caused by excessive levels of cortisol). Corcept filed for a New Drug Application (NDA) for Korlym (a 300 mg mifepristone tablet) to control hyperglycemia secondary to hypercortisolism in certain patients with Cushing’s syndrome. The NDA application was approved with a few post marketing requirements, one including a drug-drug interaction clinical trial to determine a quantitative estimate of the change in exposure of mifepristone following co-administration of ketoconazole (a strong CYP3A inhibitor). A memorandum provided by the FDA explained that “[t]he degree of change in exposure of mifepristone when co-administered with strong CYP3A inhibitors is unknown. . .”.

In approving Corcept’s NDA, the FDA also approved the Korlym label recommending a dose of 300 mg once daily and allowing for increasing dosage in 300 mg increments to a maximum 1200 mg once daily. In addition, the label warned against using mifepristone with strong CYP3A inhibitors and limited the dose to 300 mg per day when used with strong CYP3A inhibitors.

Corcept conducted the drug-drug interaction study and collected data on co-administration of mifepristone with a strong CYP3A inhibitor and received the ‘214 patent.

Teva sought post-grant review after Corcept asserted the ‘214 patent in district court, arguing that the claims would have been obvious based on the Korlym label and the FDA memorandum, optionally in combination with FDA guidance on drug-drug interaction. Furthermore, Teva provided an expert declaration of Dr. Greenblatt opining that it was reasonably likely that 600 mg mifepristone would be well tolerated and therapeutically effective when co-administered with a strong CYP3A inhibitor.

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) found that Teva had failed to prove that claims 1-13 would have been obvious. The PTAB construed the claims to require safe administration of mifepristone, and that Teva failed to show that one of ordinary skill in the art would have had a reasonable expectation of success for safe co-administration of more than 300 mg mifepristone with a strong CYP3A inhibitor.

Teva asserted that the PTAB had committed two errors: (1) that the PTAB erred in requiring precise predictability rather than a reasonable expectation of success, and (2) that the PTAB erred when it found Teva had failed to prove the general working conditions (ranges) disclosed in the prior art encompassed the claimed invention. The CAFC did not agree.

1. Reasonable Expectation of Success

The reasonable expectation of success analysis must be tied to the scope of the claims.

Claim 1 is representative:

A method of treating Cushing’s syndrome in a patient who is taking an original once-daily dose of 1200 mg or 900 mg per day of mifepristone, comprising the steps of:

reducing the original once-daily dose to an adjusted once-daily dose of 600 mg mifepristone,

administering the adjusted once-daily dose of 600 mg mifepristone and a strongCYP3A inhibitor to the patient,

wherein said strong CYP3A inhibitor is selected from the group consisting of ketoconazole, itraconazole, nefazodone, ritonavir, nelfmavir, indinavir, boceprevir, clarithromycin, conivaptan, lopinavir, posaconazole, saquinavir, telaprevir, cobicistat, troleandomycin, tipranivir, paritaprevir, and voriconazole.

The claims require safe co-administration of a specific amount of mifepristone with a strong CYP3A inhibitor. Teva failed to establish that one would have reasonably expected co-administration of more than 300 mg mifepristone with a strong CPY3A inhibitor to be safe for treatment of Cushing’s syndrome. The PTAB went further to find that one of ordinary skill in the art would have had no expectation of success. Although not in the CAFC’s opinion, the deposition testimony of Teva’s expert (Dr. Greenblatt) was devastating.From the deposition:

[Patent Owner’s Counsel]: Well, okay. With all those assumptions built into this, was this — was the result set forth here that there was little to no increase in adverse events, was that result predictable?

[Dr. Greenblatt]: It’s — the result is neither predictable or unpredictable. It is what it is. It’s the study was done as mandated by the FDA to get at the truth, and here’s the outcome of the study.

[Patent Owner’s Counsel]: So a person of skill in the art would not have expected there to be no increase in adverse events?

[Dr. Greenblatt]: The study was done to, in part, to answer that question, not to address an expectation. I don’t believe that there would be any expectation. You don’t know what’s going to happen, which is why you do the study.

[Patent Owner’s Counsel]: So if the same testing had shown that a dose of 600 mg mifepristone could not be safely administered with ketoconazole, would that have been expected by a person of skill in the art?

. . .

[Dr. Greenblatt]: Yeah, the same answer. I don’t think there’s an expectation. You’re doing the study to find out what the result is to get the scientific truth.

The PTAB had discredited Dr. Greenblatt’s pre-institution testimony based on this post-institution testimony which unequivocally stated that one of ordinary skill would have no expectation as to whether 600 mg of mifepristone and ketoconazole would be safe. 2. Prior Art Range Precedence

Teva had asserted that the sole administration of mifepristone up to 1200 mg was an overlap in the range required by claim 1. This argument failed because the evidence of recorded only supported that the general working conditions for co-administration was shown to be 300 mg/day. As such, there was no overlap. Thus. The PTAB’s finding that the prior art ranges do not overlap was supported by substantial evidence.

Takeaways

- Make sure your expert is prepared.

- Obviousness based on the reasonable-expectation-of-success analysis must be tied to the scope of the claims.

- General working conditions in the prior art need to be analyzed with respect to the scope of the claims.

Federal Circuit Restricts Ranges for lack of Written Description

| January 19, 2022

Indivior UK LTD., v. Dr. Reddy’s Labs S.A., Dr. Reddy’s Labs, Inc.

Decided on November 24, 2021

Lourie, Linn and Dyk. Opinion by Lourie. Dissent by Linn.

Summary

The Federal Circuit Court affirmed a Patent Office ruling for an IPR finding that there is lack of written description support in an application for ranges in claims of a continuation patent thereby resulting in the claims being anticipated by prior art. The Court found that the Tables in the application, relied on for support, lacked sufficient clarity as the values therein did not constitute ranges but only specific, particular examples.

Details

Indivior owns USP 9,687,454 (the ’454 patent), directed to orally dissolvable films containing therapeutic agents. The ’454 patent issued as the fifth continuation of an application filed on August 7, 2009 to which Indivior claimed the filing date.

Dr. Reddy’s Labs (DRL) petitioned for inter partes review of claims 1–5 and 7–14 at the PTAB alleging that the polymer weight percentage limitations, added to the claims by amendment, do not have written description support in the application as filed and thus are not entitled to the benefit of its filing date. Specifically, the limitation in question of claim 1 reads:

…. about 40 wt % to about 60 wt % of a water-soluble polymeric matrix;…

Also in question was claim 8’s polymer weight percentage limitation of “about 48.2 wt %,” which the Board found that Tables 1 and 5 in the application disclose formulations from which a polymer weight of 48.2% could be calculated by a person of ordinary skill in the art.

Regarding claims 1, 7 and 12 recitations of polymer weight percentage limitations as ranges: “about 40 wt % to about 60 wt %” (claim 1) and “about 48.2 wt % to about 58.6 wt %” (claims 7 and 12), the Board found that the application does not “discuss or refer to bounded or closed ranges of polymer weight percentages.” The Board also found that a person of ordinary skill would have been led away from a particular bounded range by the application’s teaching that “[t]he film may contain any desired level of self-supporting film forming polymer.” Based thereon, the Board determined that claims 1–5, 7, and 9–14 do not have written description support in the application.

Indivior appealed the Board’s decision as to claims 1, 7 and 12 while DRL cross-appealed as to the Board’s decision as to claim 8.

Discussion

Indivior’s Appeal – Claims 1, 7 and 12

Indivior argued that the Board erred in finding that the polymer range limitations in claims 1, 7, and 12 lack written description support in the application. Indivior specifically argued that Tables 1 and 5 disclose formulations with 48.2 wt % and 58.6 wt % polymer and that the application also discloses that “the film composition contains a film forming polymer in an amount of at least 25% by weight of the composition.” Indivior argued that the combination of these disclosures encompasses the claimed ranges. DRL, countered that the application does not disclose any bounded range, only a lower endpoint and some exemplary formulations from which a skilled artisan would not have discerned any upper range endpoint.

Regarding claim 1, the Court agreed with the Board that there is no written description support in the application for the range of “about 40 wt % to about 60 wt %.” The Court noted that the range was not expressly claimed in the application; nor are the values of “40 wt %” and

“60 wt %” and a range of 40 wt % to 60 wt %.

The CAFC went on to further note that not only was there no express description of these values, various other indications of the polymeric content of the film are present in the application, rendering it even less clear that an invention of “about 40 wt % to about 60 wt %” was contemplated as an aspect of the invention. Most specifically, the Court reiterated the PTAB’s reliance on the application’s paragraph 65 statement that “[t]he film may contain any desired level of . . . polymer.” The Court asserted that this statement is contrary to Indivior’s assertion that the level of polymer should be closed and between “about 40 wt % to about 60 wt %.” of claim 1.

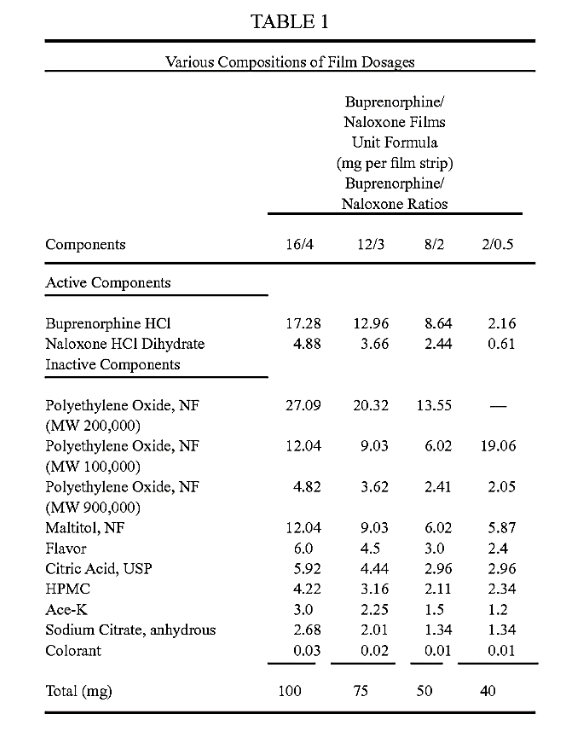

Regarding the disclosures in Tables 1 and 5 of the application, the Court noted that in Table 1 there are four polymer components of the described formulations, polyethylene oxide, NF (MW 200,000); polyethylene oxide, NF (MW 100,000); polyethylene oxide, NF (MW 900,000); and HPMC, and when they are added up, each total is within the “about 40 wt % to about 60 wt %” range. However, the CAFC found that these values do not constitute ranges but only specific, particular examples.

Thus, the Court concluded that this was insufficient written description support for the claimed ranges, stating:

Here, one must select several components, add up the individual values, determine the aggregate percentages, and then couple those aggregate percentages with other examples in the ’571 application to create an otherwise unstated range.

As such the CAFC affirmed that the Board properly determined that claims 1, 7, and 12 do not have written description support in the application and are therefore anticipated by the prior art asserted during the IPR.

DLR’s Cross-Appeal – Claim 8

Regarding claim 8, which the Board had found sufficient written description for, the Court affirmed that determination, even though, as DRL argued, the number “48.2 wt %” is not explicitly set forth in the application. The Court noted that “even though one might see some inconsistency” between this result and their ruling as to claims 1, 7 and 12 since claim 8 does not recite a range, but only a specific amount, this can be derived by selection and addition of the amounts detailed in Tables 1 and 5 of the application.

Dissent

Judge Linn dissented from the majority as to affirming the Board’s decision on Indivior’s appeal, specifically taking exception to the majority’s interpretations of the often-cited written description cases In re Wertheim and Nalpropion.

Linn particularly noted that the majority too narrowly interpreted the disclosures of the application. Specifically, Linn referred to the noted paragraph 65 of the application as a truncated text “[t]he film may contain any desired level of … polymer” to wrongly suggest that the statements about film polymer levels of “at least 25%” or “at least 50%” fail to provide clear support for the claimed “about 40 wt % to about 60 wt %” range. He asserts that the quoted passage is taken out of context and ignores the remaining part of the sentence, which expressly links the aggregate polymer percentage to the key claimed characteristics of mucoadhesion and rate of film dissolution shared by films having the stated polymer levels. He quotes the full text from paragraph 65 noting that it states that “any film forming polymers that impart the desired mucoadhesion and rate of film dissolution may be used as desired.” Linn asserts that this statement does not suggest that any polymer percentage is acceptable but oppositely explicitly identifies the essential desired characteristics possessed by the films of the claimed invention and identifies the polymer levels needed to impart the characteristics.

As to the majority’s treatment of In re Werthiem, Linn notes that the majority cites no authority that written description support for a “closed range” requires a disclosure of a closed range rather than discrete values, and there is no logical reason why such a disclosure should be required as a strict rule to show possession. He remarks that in Wertheim, the CAFC had found “[b]roadly articulated rules are particularly inappropriate in this area.” Wertheim, 541 F.2d at 263-65 (Rich, J.) and an obvious example would be a disclosure with express embodiments of 5%, 6%, 7%, 8%, 9% and 10% of a particular substance, and a continuation application that claims a range of 5-10%. Relating this back to the discussion as to the disclosures of paragraph 65 of the application, he asserts that the paragraph does disclose a closed range of “at least 25%” and “at least 50%” and in light of In re Werthiem, those ranges are no different than if restated as “25%-100%” and “50%-100%,” respectively.

Hence, Linn concludes that he would reverse the Board’s holding that claims 1, 7 and 12 do not have written description support in the application and are thus anticipated by the prior art. Linn did concur-in-part as to the majority finding that Indivior was in possession of a film with 48.2 wt % polymeric matrix as claimed in claim 8.

Takeaway

- Care needs to be taken when patent prosecutors incorporate range limitations into the claims based on disclosures within Examples and Tables. The application should clearly contain evidence that the individual Examples may be formulated into the range claimed.

No Standing and No Vacatur for Patent Licensee Seeking Review of IPR Decisions

| December 28, 2021

Apple Inc. v. Qualcomm Incorporated

Decided on November 10, 2021

Newman, Prost, and Stoll. Opinion by Prost. Dissent by Newman.

Summary

For a second time involving the same parties who had entered a license agreement as part of settlement of global patent litigation, the Federal Circuit denied standing to appeal from the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) where the underlying facts were identical to those in the previous case, except for the identity of patents at issue. The Federal Circuit also rejected the licensee’s request to vacate the PTAB decision which was found unappealable for lack of standing. The dissent argued that the mere existence of a license should not negate the licensee’s right to challenge the patent validity in Article III court.

Details

“Flashback” to Apple I

The Opinion begins by referring to Apple Inc. v. Qualcomm Inc., 992 F.3d 1378, 1385 (Fed. Cir. 2021) (“Apple I”), where Qualcomm sued Apple in a district court for infringement of patents; Apple sought an inter partes review (“IPR”) of those patents; the two companies settled all their litigation and entered a license agreement, leading to dismissal of the infringement action with prejudice; thereafter, Apple appealed a final decision of the IPR issued in favor of Qualcomm.

At issue in Apple I was Apple’s standing before the Article III court. There, Apple was found to lack standing because:

- No sufficient evidence or argument was presented that invalidity of any specific patent would change any aspect of the contractual relationship or royalty imposed on Apple.

- Apple’s evidence failed to identify any particular patent or potentially infringing activity that is tied to a risk of litigation after the license has expired.

- Apple’s invocation of the estoppel provision was insufficient to warrant standing.

Rehearing was denied en banc in Apple I.

No Standing in Deference to Apple I

The Federal Circuit dismissed for lack of standing following the precedent. Since “the operative facts are the same,” the difference in the patents between the two cases was “irrelevant.” Further, the court rejected Apple’s assertion that the previous case did not articulate the reason why a threat of litigation that would potentially result from Apple’s failure to pay the license fee and termination of the agreement does not suffice to establish standing.

Vacatur Denied

Apple asserted that if it lacks standing, the PTAB decisions should be vacated, which would otherwise frustrate future litigation involving the same patents. In so doing, Apple relied on the principle in United States v. Munsingwear, Inc., which allows vacatur of a judgement below where the case has become moot on appeal.

The Federal Circuit disagreed. First, Munsignwear was distinguished because it concerns mootness, rather than standing. The difference between the two doctrines resides in the timing: Standing relates to existence of controversy “at the outset” of the appeal whereas mootness considers existence of controversy “throughout the proceedings.” To the extent the dispute between the parties had disappeared before the appeal was filed, the case cannot “become moot.” Second, even if the mootness doctrine were applicable, the court stated that vacatur would still not be appropriate. Because the alleged mootness was caused by Apple’s own voluntary action (i.e., settlement), it could not claim the equitable remedy of vacatur.

Dissent

The dissenting opinion noted that continuing controversy existed where Apple, although agreeing to settlement and license, still disputed the validity of the licensed patents, and the potentially infringing products will likely remain on the market after the termination of the contract, which does not cover the entire life of the patents as a result of Qualcomm’s refusal of Apple’s request otherwise. The dissent also argued that denial of the standing is contrary to the statutory purposes of estoppel and right of appeal provisions under the AIA. Furthermore, citing United States v. Arthrex, Inc., 141 S. Ct. 1970 (2021) (see Cindy Chen’s previous report), which required vacatur of PTAB decisions that are unreviewable by a principle agency officer, the dissent argued that the IPR decisions in the present case should be vacated if Apple is denied the constitutional right of judicial review.

Takeaway

- In addition to confirming that the patent licensee seeking appeal from the IPR lacks Article III standing in the circumstances of the case, the Federal Circuit found that such a party also forfeited its right to vacatur of the underlying IPR decision.

- Potential consequences of settlement and license where an IPR is pending could be grave; not only could it limit the party’s ability to prove a requisite injury for standing to appeal, but also it could foreclose the remedy of vacatur, thereby affecting future re-litigation.

Lets’ B. Cereus, No Reasonable Fact Finder Could Find an Expectation of Success Based on the Teachings of a Prior Art Reference That Failed to Achieve That Which The Inventor Succeeds

| December 6, 2021

University of Strathclyde vs., Clear-Vu Lighting LLC

Circuit Judges Reyna, Clevenger and Stoll (author).

Summary:

Here, the University of Strathclyde (Strathclyde herein after) appeals from a final written decision of the Patent Trail and Appeal Board holding claims 1 to 4 of U.S. Patent No. 9,839,706 unpatentable as obvious.

The patent relates to effective sterilization methods for environmental decontamination of air and surfaces of, amongst other antibiotic resistant Gram-positive bacteria, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Specifically, sterilization is performed via photoinactivation without the need for a photosensitizing agent.

Claim 1[1] is as follows:

1. A method for disinfecting air, contact surfaces or materials by inactivating one or more pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria in the air, on the contact surfaces or on the materials, said method comprising exposing the one or more pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria to visible light without using a photosensitizer, wherein the one or more pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria are selected from the group consisting of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Coagulase-Negative Staphylococcus (CONS), Streptococcus, Enterococcus, and Clostridium species, and wherein a portion of the visible light that inactivates the one or more pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria consists of wavelengths in the range 400-420 nm, and wherein the method is performed outside of the human body and the contact surfaces or the materials are non-living.

The Board determined that claim 1 above would have been obvious over Ashkenazi in view of Nitzan. Ashkenazi is an article that discusses photoeradication of a Gram-positive bacterium, stating that “In the case of P. acnes (leading cause of acne) or other bacterial cells that produce porphyrins…. Blue light may photoinactivate the intact bacterial cells.” However, as noted by the CAFC, the methods of Ashkenazi always contained a photosensitive agent. Ashkenazi taught that increasing the light doses, the number of illuminations, and the length of time the bacteria are cultured resulted in greater inactivation.

The Nitzan article studied the effects of ALA (photosensitive agent) on Gram-positive bacteria, including MRSA. In Nitzan, for all the non-ALA MRSA cultures, it was reported therein that a 1.0 survival fraction was observed, meaning there was “no decrease in viability…after illumination” with blue light.

The Board ultimately held that Ashkenazi and Nitzan taught or suggested all the limitations of claim 1, and that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have been motivated to combine these two references, and “would have had a reasonable expectation of successfully doing so.”

Although neither of the references achieved inactivation of any bacteria without using a photosensitizer, the Board nonetheless found that a skilled artisan would have reasonably expected “some” amount of inactivation because the claims “do not require any specific amount of inactivation.”

Ultimately, the CAFC disagreed with the Boards’ findings.

Initially, the CAFC emphasized that “[T]he substantial evidence standard asks ‘whether a reasonable fact finder could have arrived at the agency’s decision,’ and ‘involves examination of the record as a whole, taking into account evidence that both justifies and detracts from an agency’s decision.’” OSI Pharms., LLC v. Apotex Inc., 939 F.3d 1375, 1381–82 (Fed. Cir. 2019) (quoting In re Gartside, 203 F.3d 1305, 1312 (Fed. Cir. 2000)).

That, “An obviousness determination generally requires a finding that “all claimed limitations are disclosed in the prior art,” PAR Pharm., Inc. v. TWI Pharms., Inc., 773 F.3d 1186, 1194 (Fed. Cir. 2014); cf. Koninklijke Philips N.V. v. Google LLC, 948 F.3d 1330, 1337–38 (Fed. Cir. 2020).

“Whether the prior art discloses a claim limitation, whether a skilled artisan would have been motivated to modify or combine teachings in the prior art, and whether she would have had a reasonable expectation of success in doing so are questions of fact. Tech. Consumer Prods., Inc. v. Lighting Sci. Grp. Corp., 955 F.3d 16, 22 (Fed. Cir. 2020); OSI Pharm., 939 F.3d at 1382.

Here, “the only dispute is whether these references teach inactivating one of the claimed Gram-positive bacteria without using a photosensitizer.” The CAFC stated that the “Board’s finding that this was taught by the combination of Ashkenazi and Nitzan is not supported by substantial evidence.”

Claim 1 requires both (i) exposing the bacterial to 400 to 420 nm blue light without using a photosensitizers and (ii) that the bacteria are inactivated as a result. Here, Ashkenazi achieves inactivation after exposure to 407 to 420 nm blue light but with a photosensitizer. On the other hand, Nitzan provides an example in which MRSA is exposed to 407 to 420 nm blue light without a photosensitizer, but there is no evidence that Nitzan successfully achieved inactivation under the conditions.

The Board agreed with Clear-Vu’s argument that a skilled artisan would have prepared a MRSA culture according to the method described in Nitzan and applied Ashkenazi’s teaching that increasing the light energy, number of illuminations, and length of time the bacteria are cultured, and so arrived at the Patented claims.

However, the CAFC held that “given neither Ashkenazi nor Nitzan teaches or suggests inactivation of any bacteria without using a photosensitizer” they failed “to see why a skilled artisan would opt to entirely omit a photosensitizer when combining these references.” The CAFC stressed that Nitzan itself disclosed that a photosensitizer-free embodiment was “wholly unsuccessful in achieving inactivation.”

Again, the CAFC emphasized that claim 1 requires both (i) exposing the bacterial to 400 to 420 nm blue light without using a photosensitizers and (ii) that the bacteria are inactivated as a result, and declined Clear-Vu’s invitation to read the inactivation limitation in isolation divorced from the claim as a whole concluding that “Obviousness cannot be based on the hindsight combination of components selectively culled from the prior art to fit the parameters of the patented invention.”

Next, the CAFC analyzed the Board’s finding on reasonable expectation of success and again, declined to agree.

The Board had relied upon (i) both parties agreeing that MRSA naturally produces at least some amount of endogenous porphyrins and (ii) Ashkenazi’s teaching that “blue light may” inactivate “other bacterial cells that produce porphyrins.

Here, the CAFC focused on Nitzan, as evidence on record showing the opposite. The CAFC reaffirmed that “absolute predictability of success is not required, only a reasonable expectation.” In this case, where the prior art reference fails to “achieve that at which the inventors succeeded, no reasonable fact finder could find an expectation of success based on the teachings of that same prior art.”

Thus, the CAFC concluded that the Board’s finding was not supported by substantial evidence, and so reversed its obviousness determination.

Take-away:

- The substantial evidence standard asks ‘whether a reasonable fact finder could have arrived at the agency’s decision,’ and ‘involves examination of the record as a whole, taking into account evidence that both justifies and detracts from an agency’s decision.

- If a prior art reference fails to achieve that which the inventor succeeds, it can be argued that no reasonable fact finder could find an expectation of success based thereon.

[1] Claim 2 depends on claim 1. Claim 3 is independent, but contains the same contested features highlighted above in claim 1. Claim 4 is dependent on claim 3.

Prosecution history disclaimer dooms infringement case for patentee

| November 22, 2021

Traxcell Technologies, LLC v. Nokia Solutions and Networks

Decided on October 12, 2021

Prost, O’Malley, and Stoll (opinion by Prost)

Summary

Patentee’s arguments during prosecution distinguishing the claimed invention over prior art were found to be clear and unmistakable disclaimer of certain meanings of the disputed claim terms. The prosecution history disclaimer resulted in claim constructions that favored the accused infringer and compelled a determination of non-infringement.

Details

Traxcell Technologies LLC specializes in navigation technologies. The company was founded by Mark Reed, who is also the sole inventor behind U.S. Patent Nos. 8,977,284, 9,510,320, and 9,642,024 that Traxcell accused Nokia of infringing.

The 284, 320, and 024 patents are directly related to each other as grandparent, parent, and child, respectively. The three patents are concerned with self-optimizing wireless network technology. Specifically, the patents claim systems and methods for measuring the performance and location of a wireless device (for example, a phone), in order to make “corrective actions” to or tune a wireless network to improve communications between the wireless device and the network.

The asserted claims from the three patents require a “first computer” (or in some of the asserted claims, simply “computer”) that is configured to perform several functions related to the “location” of a mobile wireless device.

Central to the parties’ dispute was the proper constructions of “first computer” and “location”.

Nokia’s accused geolocation system was undisputedly a self-optimizing network product. Nokia’s system performed similar functions as those claimed in the asserted computers, but across multiple computers. Nokia’s system also collected performance information for mobile wireless devices located within 50-meter-by-50-meter grids.

To avoid infringement, Nokia argued that the claimed “first computer” required a single computer performing the claimed functions, and that the claimed “location” required more than the use of a grid.

On the other hand, wanting to capture Nokia’s products, Traxcell argued that the claimed “first computer” encompassed embodiments in which the claimed functions were spread among multiple computers, and that the claimed “location” plainly included a grid-based location.

Unfortunately for Traxcell, their arguments did not stand a chance against the prosecution histories of the asserted patents.

The doctrine of prosecution history disclaimer “preclud[es] patentees from recapturing through claim interpretation specific meanings disclaimed during prosecution”. Omega Eng’g, Inc. v. Raytek Corp., 334 F.3d 1314, 1323 (Fed. Cir. 2003). “Prosecution disclaimer can arise from both claim amendments and arguments”. SpeedTrack, Inc. v. Amazon.com, 998 F.3d 1373, 1379 (Fed. Cir. 2021). “An applicant’s argument that a prior art reference is distinguishable on a particular ground can serve as a disclaimer of claim scope even if the applicant distinguishes the reference on other grounds as well”. Id. at 1380. For there to be disclaimer, the patentee must have “clearly and unmistakably” disavowed a certain meaning of the claim.

Of the three asserted patents, the 284 patent had the most protracted prosecution, with six rounds of rejections. And it was the prosecution history of the 284 patent that provided the fodder for the district court’s claim constructions. Incidentally, the 284 patent was also the only one of the three asserted patents prosecuted by the inventor, Mark Reed, himself.

During claim construction, the district court construed the terms “first computer” and “computer” to mean a single computer that could performed the various claimed functions.

The district court first looked to the plain language of the claims. The claim language recites “a first computer” or “a computer” that performs a function, and then recites that “the first computer” or “the computer” performs several additional functions. The district court determined that the claims plainly tied the claimed functions to a single computer, and that “it would defy the concept of antecedent basis” for the claims to refer back to “the first computer” or “the computer”, if the corresponding tasks were actually performed by a different computer.

The intrinsic evidence that convinced the district court of its claim construction was, however, the prosecution history of the 284 patent.

During prosecution, in a 67-page response, Mr. Reed argued explicitly and at length, in a section titled “Single computer needed in Reed et al. [i.e., the pending application] v. additional software needed in Andersson et al. [i.e., the prior art]”, that the claimed invention requiring just one computer distinguished over the prior art system using multiple computers. The district court quoted extensively from this response as intrinsic evidence supporting its claim construction.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court’s claim construction, quoting still more passages from the same response as evidence that the patentee “clearly and unmistakably disclaimed the use of multiple computers”.

Next, the district court addressed the term “location”. The district court construed the term to mean a “location that is not merely a position in a grid pattern”.

Here, the district court’s claim construction relied almost exclusively on arguments that Reed made during prosecution of the 284 patent. Referring again to the same 67-page response, the district court noted that Mr. Reed explicitly argued, in a section titled “Grid pattern not required in Reed et al. v. grid pattern required in Steer et al.”, that the claimed invention distinguished over the prior art because the claimed invention operated without the limitation of a grid pattern, and that the absence of a grid pattern permitted finer tuning of the network system.

And again, the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court’s claim construction, finding that “the disclaimer here was clear and unmistakable”.

The claim constructions favored Nokia’s non-infringement arguments that its system lacked the single-computer, non-grid-pattern-based-location limitations of the asserted claims. Accordingly, the district court found, and the Federal Circuit affirmed, that Nokia’s system did not infringe the 284, 320, and 024 patents.

Traxcell made an interesting argument on appeal—specifically, the disclaimer found by the district court was too broad and a narrower disclaimer would have been enough to overcome the prior art. Traxcell seemed to be borrowing from the doctrine of prosecution history estoppel. Under that doctrine, arguments or amendments made during prosecution to obtain allowance of a patent creates prosecution history estoppel that limits the range of equivalents available under the doctrine of equivalents.

However, the Federal Circuit was unsympathetic to Traxcell’s argument, explaining that Traxcell was held “to the actual arguments made, not the arguments that could have been made”. The Federal Circuit also noted that “it frequently happens that patentees surrender more…than may have been absolutely necessary to avoid particular prior art”.

Mr. Reed’s somewhat unsophisticated prosecution of the 284 patent was in sharp contrast to the prosecution of the related 320 and 024 patents, which were handled by a patent attorney. The prosecution histories of the 320 and 024 patents said very little about the cited prior art, even less about the claimed invention. In addition, whereas Mr. Reed editorialized on various claimed features during prosecution of the 284 patent, the prosecution histories of the 320 and 024 patents rarely even paraphrased the claims.

Takeaways

- Avoid gratuitous remarks that define or characterize the claimed invention or the prior art during prosecution. Quote the claim language directly and avoid paraphrasing the claim language, as the paraphrases risk being construed later as a narrowing characterization of the claimed invention.

- Avoid claim amendments that are not necessary to distinguish over the prior art.

- The prosecution history of a patent can affect the construction of claims in other patents in the same family, even when the claim language is not identical. Be mindful about how arguments and/or amendments made in one application may be used against other related applications.

DESIGN CLAIM IS LIMITED TO AN ARTICLE OF MANUFACTURE IDENTIFIED IN THE CLAIM

| November 8, 2021

In Re: Surgisil, L.L.P., Peter Raphael, Scott Harris

Decided on October 4, 2021

Moore (author), Newman, and O’Malley

Summary:

The Federal Circuit reversed the PTAB’s anticipation decision on a claim of SurgiSil’s ’550 application because a design claim should be limited to an article of manufacture identified in the claim. The Federal Circuit held that since the claim in the ’550 application identified a lip implant, the claim is limited to lip implants and does not cover other article of manufacture. The CAFC held that since the Blick reference discloses an art tool rather than a lip implant, the PTAB’s anticipation finding is not correct.

Details:

The ’550 application

SurgiSil’s ’550 application claims an ornamental design for a lip implant[1] as shown below:

The examiner rejected a claim of the ’550 application as being anticipated by Blick, which discloses an art tool called stump as shown below:

The PTAB

The PTAB affirmed the examiner’s decision and found that the differences between the claimed design in the ’550 application and Blick are minor.

The PTAB rejected SurgiSil’s argument that Blick discloses a “very different” article of manufacture than a lip implant reasoning that “it is appropriate to ignore the identification of manufacture in the claim language” and “whether a reference is analogous art is irrelevant to whether that reference anticipates.”

The Federal Circuit

The CAFC reviewed the PTAB’s legal conclusion that the article of manufacture identified in the claims is not limiting de novo. The CAFC ultimately held that the PTAB erred as a matter of law.

By citing 35 U.S.C. §171(a) (“Whoever invents any new, original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.”), the CAFC held that a design claim is limited to the article of manufacture identified in the claim.

The CAFC also cited a case called Curver Luxembourg, SARL v. Home Expressions Inc., 938 F.3d 1334, 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2019)[2] and the MPEP to hold that the claim at issue should be limited to the particular article of manufacture identified in the claim.

The CAFC held that since the claim identified a lip implant, the claim is limited to lip implants and does not cover other article of manufacture.

The CAFC held that since Blick discloses an art tool rather than a lip implant, the PTAB’s anticipation finding is not correct.

Therefore, the CAFC reversed the PTAB’s decision.

Takeaway:

- It would certainly be easier to obtain design patents going forward. Can Applicant obtain design patents by using a known design in the art and applying to a new article of manufacture?