THE MORE YOU CLAIM, THE MORE YOU MUST ENABLE

| July 12, 2023

Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi

Decided: May 18, 2023

Supreme Court of the United States. Opinion by Justice Gorsuch

Summary:

Amgen owns patents covering antibodies that help reduce levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. Amgen sued Sanofi for infringement of its patents in district court. Sanofi raised the defense of invalidity for lack of enablement because while Amgen provided amino acid sequences for 26 antibodies, the claims cover potentially millions more undisclosed antibodies. The district court granted a motion for JMOL for invalidity due to lack of enablement, the CAFC affirmed, and the Supreme Court affirmed.

Details:

Amgen’s patents are to PCSK9 inhibitors. PCSK9 is a naturally occurring protein that binds to and degrades LDL receptors. PCSK9 causes problems due to degradation of LDL receptors because LDL receptors extract LDL cholesterol from the bloodstream. A method used to inhibit PCSK9 is to create antibodies that bind to a particular region of PCSK9 referred to as the “sweet spot” which is a sequence of 15 amino acids out of PCSK9’s 692 total amino acids. An antibody that binds to the sweet spot can prevent PCSK9 from binding to and degrading LDL receptors. Amgen developed a drug named REPATHA and Sanofi developed a drug named PRALUENT, both of which provide a distinct antibody with its own unique amino acid sequence. In 2011, Amgen and Sanofi received patents covering the antibody used in their respective drugs.

The patents at issue are U.S. Patent Nos. 8,829,165 and 8,859,741 issued in 2014 which relate back to Amgen’s 2011 patent. These patents are different from the 2011 patents in that they claim the entire genus of antibodies that (1) “bind to specific amino acid residues on PCSK9,” and (2) “block PCSK9 from binding to LDL receptors.” The relevant claims are provided:

Claims of the ‘165 patent:

1. An isolated monoclonal antibody, wherein, when bound to PCSK9, the monoclonal antibody binds to at least one of the following residues: S153, I154, P155, R194, D238, A239, I369, S372, D374, C375, T377, C378, F379, V380, or S381 of SEQ ID NO:3, and wherein the monoclonal antibody blocks binding of PCSK9 to LDLR.

19. The isolated monoclonal antibody of claim 1 wherein the isolated monoclonal antibody binds to at least two of the following residues S153, I154, P155, R194, D238, A239, I369, S372, D374, C375, T377, C378, F379, V380, or S381 of PCSK9 listed in SEQ ID NO:3.

29. A pharmaceutical composition comprising an isolated monoclonal antibody, wherein the isolated monoclonal antibody binds to at least two of the following residues S153, I154, P155, R194, D238, A239, I369, S372, D374, C375, T377, C378, F379, V380, or S381 of PCSK9 listed in SEQ ID NO: 3 and blocks the binding of PCSK9 to LDLR by at least 80%.

Claims of the ‘741 patent:

1. An isolated monoclonal antibody that binds to PCSK9, wherein the isolated monoclonal antibody binds an epitope on PCSK9 comprising at least one of residues 237 or 238 of SEQ ID NO: 3, and wherein the monoclonal antibody blocks binding of PCSK9 to LDLR.

2. The isolated monoclonal antibody of claim 1, wherein the isolated monoclonal antibody is a neutralizing antibody.

7. The isolated monoclonal antibody of claim 2, wherein the epitope is a functional epitope.

In its application, Amgen identified the amino acid sequences of 26 antibodies that perform these two functions. Amgen provided two methods to make other antibodies that perform the described binding and blocking functions. Amgen refers to the first method as the “roadmap,” which provides instructions to:

(1) generate a range of antibodies in the lab; (2) test those antibodies to determine whether any bind to PCSK9; (3) test those antibodies that bind to PCSK9 to determine whether any bind to the sweet spot as described in the claims; and (4) test those antibodies that bind to the sweet spot as described in the claims to determine whether any block PCSK9 from binding to LDL receptors.

Amgen refers to the second method as “conservative substitution” which provides instructions to:

(1) start with an antibody known to perform the described functions; (2) replace select amino acids in the antibody with other amino acids known to have similar properties; and (3) test the resulting antibody to see if it also performs the described functions.

Amgen sued Sanofi for infringement of claims 19 and 29 of the ‘165 patent and claim 7 of the ‘741 patent. Sanofi raised the defense of invalidity because Amgen had not enabled a person skilled in the art to make and use all of the antibodies that perform the two functions Amgen described in the claims. Sanofi argued that Amgen’s claims cover potentially millions more undisclosed antibodies that perform the same two functions than the 26 antibodies identified in the patent.

The court provided an explanation of the law and policy regarding the enablement requirement. 35 U.S.C. § 112 requires that a specification include “a written description of the invention, and of the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art … to make and use the same.” The court stated:

the law secures for the public its benefit of the patent bargain by ensuring that, upon the expiration of [the patent], the knowledge of the invention [i]nures to the people, who are thus enabled without restriction to practice it.

The court stated that “the specification must enable the full scope of the invention as defined by its claims.” Specifically, the court stated:

If a patent claims an entire class of processes, machines, manufactures, or compositions of matter, the patent’s specification must enable a person skilled in the art to make and use the entire class.

The court emphasized that the enablement requirement does not always require a description of how to make and use every single embodiment within a claimed class. A few examples may suffice if the specification also provides “some general quality … running through” the class. A specification may also not be inadequate just because it leaves a skilled artisan to engage in some measure of adaptation or testing, i.e., a specification may call for a reasonable amount of experimentation to make and use a patented invention. “What is reasonable in any case will depend on the nature of the invention and the underlying art.”

Regarding this case, the court stated that while the 26 exemplary antibodies provided by Amgen are enabled by the specification, the claims are much broader than the specific 26 antibodies. And even allowing for a reasonable degree of experimentation, Amgen has failed to enable the full scope of the claims.

The court stated that Amgen seeks to monopolize an entire class of things defined by their function and that this class includes a vast number of antibodies in addition to the 26 that Amgen has described by their amino acid sequences. “[T]he more a party claims, the broader the monopoly it demands, the more it must enable.”

Amgen argued that the claims are enabled because scientists can make and use every undisclosed but functional antibody if they simply follow Amgen’s “roadmap” or its proposal for “conservative substitution.” The court stated that these instructions amount to two research assignments and that they leave scientists “forced to engage in painstaking experimentation to see what works.” The court referred to Amgent’s two methods as “a hunting license.”

Comments

The key takeaway from this case is that the broader your claims are, the more your specification must enable. If it is difficult to show enablement for every embodiment claimed, then make sure your specification describes some general quality throughout the class or genus. A reasonable amount of experimentation is permissible for enablement, but reasonableness will depend on the nature of the invention and the underlying art.

Joint Inventorship Gone Up In Smoke For Want of Significant Contribution

| June 16, 2023

HIP, INC. v. HORMEL FOODS CORPORATION

Decided: May 2, 2023

Before Lourie, Clevenger, and Taranto. Opinion by Lourie.

Summary

The CAFC held that an alleged inventor did not make a contribution sufficiently significant in quality to establish joint inventorship to an issued patent, where the alleged contributed concept was only minimally mentioned throughout the entirety of the patent document including the specification, drawings and claims.

Details

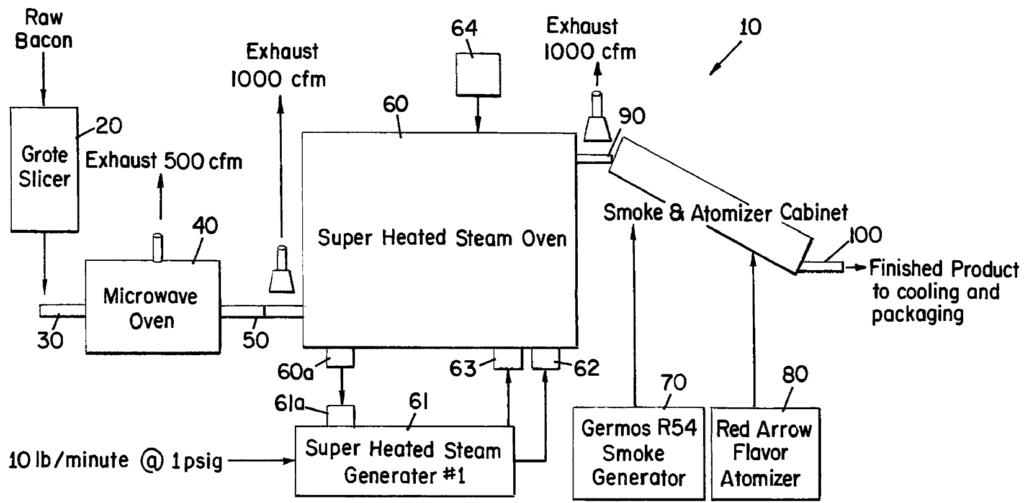

Hormel Foods Corporation (“Hormel”) owns U.S. Patent 9,980,498 (the “’498 patent”) relating to production of precooked bacon. While a traditional bacon producer would “precook” or prepare the bacon prior to sale by a certain type of oven, such as microwave or steam oven, the invention uses a two-step, hybrid oven system to improve the precooking process. FIG. 1, reproduced below, depicts a principle embodiment where a microwave oven 40 initially heats bacon so as to form a coating of melted fat around the meat piece, followed by a super heated steam oven 60 equipped with external steam source 61 for further cooking to a finishing temperature:

Per the ‘498 patent, the first step of forming the “fat barrier” protects the underlying meat from condensation and resulting dilution of flavor, whereas the second step using the external gas source prevents the oven’s internal surfaces from becoming hotter than the smoke point of bacon fat, which would otherwise cause off flavor of the resulting product.

The ’498 patent includes independent claims 1, 5 and 13, defining the inventive method using slightly different languages from each other. As relevant on appeal, claims 1 and 13 both recite a particular mode of cooking in the first step of the hybrid system as “preheating … with a microwave oven,” whereas claim 5 recites three alternative preheating techniques using a Markush language, “selected from the group consisting of a microwave oven, an infrared oven, and hot air.”

As part of its R&D efforts toward the improved precooking process, Hormel contacted Unitherm Food Systems, Inc. (“Unitherm”), now HIP, a manufacturer of cooking machinery such as industrial ovens. The parties jointly agreed to develop an oven to be used in a two-step cooking process. The alleged inventor in question, David Howard of Unitherm, was involved in those meetings and testing process where he allegedly disclosed an infrared heating concept to Hormel. As Hormel’s further R&D—including testing with their own facility instead of Unitherm’s facility—eventually led to the discovery of the inventive two-step process, Hormel filed for a patent. The resulting ’498 patent named four inventors, which did not include Howard.

HIP sued Hormel in the District Court for the District of Delaware, alleging that Howard was either the sole inventor or a joint inventor of the ’498 patent. HIP argued, among other things, that Howard contributed to preheating with an infrared oven, the concept recited in independent claim 5. The district court held that although Howard was not the sole inventor, his contribution of the infrared oven concept made him a joint inventor of the ’498 patent. Hormel appealed.

On appeal, Hormel argued, among other things,[1] that Howard was not a joint inventor because the infrared oven concept was well known, and his alleged contribution was insignificant in quality relative to the extent of the full invention.

Specifically, the joint inventorship issue was argued based on the three-part test set forth in Pannu v. Iolab Corp., 155 F.3d 1344, 1351. Under Pannu, to qualify as an additional joint inventor, one must have:

(1) contributed in some significant manner to the conception of the invention;

(2) made a contribution to the claimed invention that is not insignificant in quality, when that contribution is measured against the dimension of the full invention; and

(3) did more than merely explain to the real inventors well-known concepts and/or the current state of the art.

Hormel asserted that Howard met none of the three factors, and HIP countered that each and every factor was met so as to establish joint inventorship.

The CAFC ultimately sided with Hormel. The CAFC focused its analysis on the second Pannu factor, noting specific circumstances:

- Small # of times mentioned in the specification: The alleged contribution, preheating with an infrared oven, is “mentioned only once in the … specification as an alternative heating method to a microwave oven.”

- Small # of times mentioned in the claims: The alleged contribution is “recited only once in a single claim” whereas the two other independent claims recite preheating with a microwave oven, with no mention of an infrared oven.

- Presence of a more significant alternative in the disclosure: The alternative to the alleged contribution, preheating with a microwave oven, “feature[s] prominently throughout the specification, claims, and figures.”

- Specification focused on the alternative: All the specific examples disclosed in the specification are limited to embodiments using preheating with a microwave oven.

- Drawings focused on the alternative: All the figures, including Figure 1 primarily depicting the operating principles of the claimed invention, are limited to embodiments based on preheating with a microwave oven.

Noting that the entirety of the ’498 patent disclosure supports insignificance in quality of the alleged contribution per the second part of Pannu test, the CAFC concluded that Howard did not qualify as a joint inventor. Lastly, the CAFC noted that there was no need to address the other Pannu factors “as the failure to meet any one factor is dispositive on the question of inventorship.”

Takeaway

This case provides a reminder of the role a patent disclosure may play in determining the question of joint inventorship. In particular, although the second Pannu factor requires the inventor’s contribution to be “not insignificant in quality” (emphasis added), in certain circumstances, the amount of mentions made of the alleged contributed concept in the patent, along with other considerations such as the primary focus of the patent as discerned from the entire disclosure, may influence the determination of joint inventorship.

[1] Hormel’s second main argument challenges insufficiency of corroboration of Howard’s testimony, the question rendered moot due to the decision on the significance of the alleged contribution.

CAFC upheld ITC’s ruling under the ‘Infrequently Applied’ Anderson two-step test regarding the enablement of open-ended ranges

| June 8, 2023

FS.com Inc. v. ITC and Corning Optical Corp.

Decided: April 20, 2023

Before Moore, Prost and Hughes. Opinion by Moore.

Summary:

Corning filed a complaint with the ITC alleging FS was violating §337 of the Tariff Act of 1930, as amended (19 U.S.C. 1337), (a.k.a ‘unfair import’) by importing high-density fiber optic equipment that infringed several of their patents – U.S. Patent Nos. 9,020,320; 10,444,456; 10,120,153; and 8,712,206. The patents relate to fiber optic technology commonly used in data centers.

The Commission ultimately determined that FS’ importation of the high-density fiber optic equipment violated §337 and issued a general exclusion order prohibiting the importation of infringing high-density fiber optic equipment and components thereof and a cease-and-desist order directed to FS.

Subsequently, FS appealed the Commission’s determination that the claims of the ’320 and ’456 patents are enabled and its claim construction of “a front opening” in the ’206 patent.

ISSUE 1: ENABLEMENT

FS challenges the Commission’s determination that claims 1 and 3 of the ’320 patent and claims 11, 12, 15, 16, and 21 of the ’456 patent are enabled. These claims recite, in part, “a fiber optic connection density of at least ninety-eight (98) fiber optic connections per U space” or “a fiber optic connection of at least one hundred forty-four (144) fiber optic connections per U space.” FS argued these open-ended density ranges are not enabled because the specification only enables up to 144 fiber optic connections per U space.

A patent’s specification must describe the invention and “the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art to which it pertains . . . to make and use the same.” 35 U.S.C. § 112(a). To enable, “the specification of a patent must teach those skilled in the art how to make and use the full scope of the claimed invention without undue experimentation.”

In determining enablement, the Commission applied the two-part standard set forth in Anderson Corp. v. Fiber Composites, LLC, 474 F.3d 1361 (Fed. Cir. 2007):

[O]pen-ended claims are not inherently improper; as for all claims their appropriateness depends on the particular facts of the invention, the disclosure, and the prior art. They may be supported if there is an inherent, albeit not precisely known, upper limit and the specification enables one of skill in the art to approach that limit.

Although the CAFC acknowledged that the Anderson test is infrequently applied, both FS and Corning agreed that the test governed their legal dispute. In applying this standard, the Commission determined the challenged claims were enabled because skilled artisans would understand the claims to have an inherent upper limit and that the specification enables skilled artisans to approach that limit.

The CAFC agreed, understanding the Commission’s opinion as determining there is an inherent upper limit of about 144 connections per U space. See Appellant’s Opening Br. at 51 (“The only potential finding by the Commission of an inherent upper limit to the open-ended claims is approximately 144 connections per 1U space.”). Specifically, that determination was based on the Commission’s finding that skilled artisans would have understood, as of the ’320 and ’456 patent’s shared priority date (August 2008), that densities substantially above 144 connections per U space were technologically infeasible. This was supported by expert testimony.

ISSUE 2: CLAIM CONSTRUCTION

The Commission construed “a front opening” in claim 14 of the ’206 patent as encompassing one or more openings. FS argued the proper construction of “a front opening” is limited to a single front opening and therefore its modules, which contain multiple openings separated by material or dividers, do not infringe claims 22 and 23. The CAFC disagreed.

The CAFC held that, generally, the terms “a” or “an” in a patent claim mean “one or more,” unless the patentee evinces a clear intent to limit “a” or “an” to “one.” 01 Communique Lab’y, Inc. v. LogMeIn, Inc., 687 F.3d 1292, 1297 (Fed. Cir. 2012). The CAFC concluded here that the claim language and written description did not demonstrate a clear intent to depart from this general rule.

Comments:

- Open-end ranges are not automatically improper. If such a range is required/desired during prosecution, apply the two-part standard set forth in Anderson: (1) is there inherent, albeit not precisely known, support for an upper limit and (2) does the specification enables one of skill in the art to approach that limit.

- The terms “a” or “an” in a patent claim remain to mean “one or more,” unless the patentee evinces a clear intent to limit “a” or “an” to “one.”

File your patent application before attending a trade show to showcase your products

| May 26, 2023

Minerva Surgical, Inc. v. Hologic, Inc., Cytyc Surgical Products, LLC

Decided: February 15, 2023

Summary:

Minerva Surgical, Inc. sued Hologic, Inc. and Cytyc Surgical Products, LLC in the District of Delaware for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 9,186,208 (“the ’208 patent”). Hologic moved for summary judgment of invalidity, arguing that the ’208 patent claims were anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b). The district court granted summary judgment that the asserted claims are anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) because the patented technology was “in public use,” and the technology was “ready for patenting.” The Federal Circuit held that the district court correctly determined that Minerva’s disclosure of their constituted the invention being “in public use,” and that the device was “ready for patenting.” Therefore, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s grant of summary judgment.

Details:

Minerva Surgical, Inc. sued Hologic, Inc. and Cytyc Surgical Products, LLC in the District of Delaware for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 9,186,208 (“the ’208 patent”).

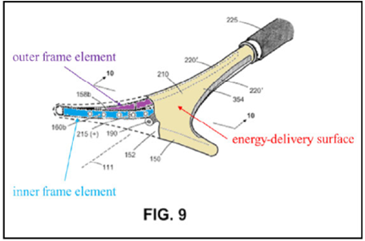

The ’208 patent is directed to surgical devices for a procedure called “endometrial ablation” for stopping or reducing abnormal uterine bleeding. This procedure includes inserting a device having an energy-delivery surface into a patient’s uterus, expanding the surface, energizing the surface to “ablate” or destroy the endometrial lining of the patient’s uterus, and removing the surface.

The application for the’208 patent was filed on November 2, 2021 and claims a priority date of November 7, 2011. Therefore, the critical date for the ’208 patent is November 7, 2010.

The ’208 patent

Independent claim 13 is a representative claim:

A system for endometrial ablation comprising:

an elongated shaft with a working end having an axis and comprising a compliant energy-delivery surface actuatable by an interior expandable-contractable frame;

the surface expandable to a selected planar triangular shape configured for deployment to engage the walls of a patient’s uterine cavity;

wherein the frame has flexible outer elements in lateral contact with the compliant surface and flexible inner elements not in said lateral contact, wherein the inner and outer elements have substantially dissimilar material properties.

The appeal focused on the claim term, “the inner and outer elements have substantially dissimilar material properties” (“SDMP” term”).

District Court

After discovery, Hologic moved for summary judgment of invalidity, arguing that the ’208 patent claims were anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b).

The district court granted summary judgment that the asserted claims are anticipated under the public use bar of pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) because of the following reasons:

First, the patented technology was “in public use” because Minerva disclosed fifteen devices (“Aurora”) at an event, where Minerva showcased them at a booth, in meeting with interested parties, and in a technical presentation. Also, Minerva did not disclose them under any confidentiality obligations.

Second, the technology was “ready for patenting” because Minerva created working prototypes and enabling technical documents.

Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit reviewed a district court’s grant of summary judgment under the law of the regional circuit (Third Circuit).

The Federal Circuit held that “the public use bar is triggered ‘where, before the critical date, the invention is [(1)] in public use and [(2)] ready for patenting.’”

The “in public use” element is satisfied if the invention “was accessible to the public or was commercially exploited” by the invention.

“Ready for patenting” requirement can be shown in two ways – “by proof of reduction to practice before the critical date” and “by proof that prior to the critical date the inventor had prepared drawings or other descriptions of the invention that were sufficiently specific to enable a person skilled in the art to practice the invention.”

The Federal Circuit held that disclosing the Aurora device at the event (American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (“AAGL 2009”)) constituted the invention being “in public use” because this event included attendees who were critical to Minerva’s business, and Minerva’s disclosure of their devices included showcasing them at a booth, in meeting with interested parties, and in a technical presentation.

The Federal Circuit noted that AAGL 2009 was the “Super Bowl” of the industry and was open to the public, and that Minerva had incentives to showcase their products to the attendees. Also, Minerva sponsored a presentation by one of their board members to highlight their products and pitched their products to industry members, who were able to see how they operate.

The Federal Circuit also noted that there were no “confidentiality obligations imposed upon” those who observed Minerva’s devices, and that the attendees were not required to sign non-disclosure agreements.

The Federal Circuit also held that Minerva’s Aurora devices at the event disclosed the SDMP term because Minerva’s documentation about this device from before and shortly after the event disclosed this device having the SDMP terms or praises benefits derived from this device having the SDMP technology.

The Federal Circuit held that the record clearly showed that Minerva reduced the invention to practice by creating working prototypes that embodied the claim and worked for the intended purpose.

The Federal Circuit noted that there was documentation “sufficiently specific to enable a person skilled in the art to practice the invention” of the disputed SDMP term. Here, the documentation included the drawings and detailed descriptions in the lab notebook pages disclosing a device with the SDMP term.

Therefore, the Federal Circuit held that the district court correctly determined that Minerva’s disclosure of the Aurora device constituted the invention being “in public use” and that the device was “ready for patenting.”

Accordingly, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s grant of summary judgment because there are no genuine factual disputes, and Hologic is entitled to judgment as a matter of law that the ’208 patent is anticipated under the public use bar of § 102(b).

Takeaway:

- File your patent application before attending a trade show to showcase your products.

- Have the attendees of the trade show sign non-disclosure agreements, if necessary.

Tags: 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) > confidentiality > critical date > enablement > pre-AIA > prototype > public use > reduction to practice > summary judgment

Common Sense Still Applies In Claim Construction

| May 13, 2023

Alterwan, Inc. v Amazon.com Inc

Decided: March 13, 2023

Before Lourie, Dyk, Stoll (Opinion by Dyk)

Summary:

For a claim term “non-blocking bandwidth,” the district court accepted the applicant-as-his-own-lexicographer definition set forth in the specification to mean “a bandwidth that will always be available and will always be sufficient.” This meant that bandwidth must be available even when the Internet is down – which is impossible (and hence, the parties’ agreed-upon stipulation of non-infringement with this claim interpretation). Courts will not rewrite “unambiguous” claim language to cure such absurd positions or to sustain validity. But, when the claim language is “not unambiguous” concerning the disputed interpretation, common sense applies in claim construction, especially in view of the proper context for the source of the applicant-as-his-own-lexicographer definition.

Procedural History:

Alterwan sued Amazon for patent infringement. After a Markman hearing and motions for summary judgment by both parties, the district court changed the claim construction for “cooperating service provider” at a summary judgment hearing to be a “service provider that agrees to provide non-blocking bandwidth.” The district court construed “non-blocking bandwidth” to be “a bandwidth that will always be available and will always be sufficient” which meant that the bandwidth will be available even if the Internet is down. With this updated construction, the parties filed a stipulation and order of non-infringement of the patents-in-suit. Amazon argued, and the patentee agreed, that if the claim required bandwidth provision even when the Internet is down, Amazon could not possibly infringe. The district court entered the stipulated judgment of non-infringement and the parties appealed.

Decision:

Representative claim 1 is as follows:

An apparatus, comprising:

an interface to receive packets;

circuitry to identify those packets of the received packets corresponding to a set of one or more predetermined addresses, to identify a set of one or more transmission paths associated with the set of one or more predetermined addresses, and to select a specific transmission path from the set of one or more transmission paths; and

an interface to transmit the packets corresponding to the set of one or more predetermined addresses using the specific transmission path;

wherein

each transmission path of the set of one or more transmission paths is associated with a reserved, non-blocking bandwidth, and

the circuitry is to select the specific transmission path to be a transmission path from the [sic] set of one or more transmission paths that corresponds to a minimum link cost relative to each other transmission path in the set of one or more transmission paths.

The specification states “the quality of service problem that has plagued prior attempts is solved by providing non-blocking bandwidth (bandwidth that will always be available and will always be sufficient)…” (USP 8,595,478, col. 4, line 66 to col. 5, line 2). Accordingly, “non-blocking bandwidth” was defined by the applicant, acting as his own lexicographer, to mean “a bandwidth that will always be available and will always be sufficient.”

Normally, “[c]ourts may not redraft claims, whether to make them operable or to sustain validity” (citing, Chef Am., Inc. v. Lamb-Weston, Inc., 358 F.3d 1371, 1374 (Fed. Cir. 2004)). In Chef America, the claim limitation “heating the resulting batter-coated dough to a temperature in the range of about 400°F to 850°F” would lead to an absurd result in that the dough would be burnt. Instead, the limitation would be made operable if it recited heating the dough “at” a temperature in the range of about 400°F to 850°F. However, since the limitation at issue was unambiguous, the court declined to rewrite the claim to replace the term “to” with “at.”

However, the court noted that, “[h]ere, the claim language itself does not unambiguously require bandwidth to be available even when the Internet is inoperable.” So, “Chef America does not require us to depart from common sense in claim construction.” Without “unambiguous” claim language requiring the disputed interpretation (“a bandwidth that will always be available and will always be sufficient”), the court proceeded to check the context for the support for the disputed interpretation. That “context” included specification discussion of wide area network technology that uses the internet as a backbone, and several “quality of service” problems that arise from the use of the internet as a backbone, including latency problems in the delays for critical transmission packets getting from a source to a destination over that internet backbone. The patent’s solution was to provide “preplanned high bandwidth, low hop-count routing paths” between sites that are geographically separated. These preplanned routing paths are a “key characteristic that all species within the genus of the invention will share.” It is after this discussion that the specification then concludes “[i]n other words, the quality of service problem that has plagued prior attempts is solved by providing non-blocking bandwidth (bandwidth that will always be available and will always be sufficient) and predefining routes for the ’private tunnel’ paths between points on the internet…”

Providing bandwidth even with the Internet being down is an impossibility. The specification describes operability and transmission over the Internet as a backbone and is completely silent about provision of bandwidth when the Internet is unavailable. In context, the definitional sentence for “non-blocking bandwidth” is addressing the problem of latency (when the Internet is operational), rather than providing for bandwidth even when there is no Internet. The court’s decision does not opine on what the meaning of non-blocking bandwidth is, but holds that “it does not require bandwidth when the Internet is down.”

Takeaways:

The court will not redraft claim language during claim construction to maintain operability or sustain validity when the claim language is unambiguous. But, when the claim language is “not unambiguous,” common sense applies, especially when looking at any source of the disputed interpretation in context.

What’s the Problem? CAFC reverses PTAB for identifying the problem to be solved in finding combined references analogous when the burden was properly on the Petitioner

| May 11, 2023

Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GMBH v. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Decided: May 9, 2023

Before Reyna, Mayer and Cunningham. Opinion by Cunningham.

Summary:

The Court reverses a PTAB final written decision finding all challenged claims of Safoni’s patent unpatentable as obvious over prior art. The Court held that Mylan improperly argued a first prior art reference is analogous to another prior art reference and not the challenged patent. Therefore Mylan failed to meet its burden to establish obviousness premised on the first reference since the Board’s factual finding that the first reference is analogous to the patent-in-suit is unsupported by substantial evidence.

Background:

Mylan filed an IPR against Sanofi’s RE47,614 (“the ‘614 patent”) alleging its unpatentability in light of a combination of three prior art references: (1) U.S. Patent Application No. 2007/0021718 (“Burren”); (2) U.S. Patent No. 2,882,901 (“Venezia”); and (3) U.S. Patent No. 4,144,957 (“de Gennes”). Claim 1 of the ‘614 patent is directed to a drug delivery device with a spring washer arranged within a housing so as to exert a force on a drug carrying cartridge and to secure the cartridge against movement with respect to a cartridge retaining member, the spring washer has at least two fixing elements configured to axially and rotationally fix the spring washer relative to the housing.

Mylan asserted that Burren with Venezia taught the use of spring washers within drug-delivery devices and relied on de Gennes to add “snap-fit engagement grips” to secure the spring washer. Burren and Venezia were both within the field of a drug delivery system. However, de Gennes was non-analogous art being directed to a clutch bearing in the automotive field. Sanofi argued that the combination was improper because de Gennes was non-analogous art. Mylan responded that de Gennes was analogous in that it was relevant to the pertinent problem in the drug delivery art and cited to Burren as providing a problem which a skilled artisan may look to extraneous art to solve.

The PTAB found that Burren in combination with Venezia and de Gennes does render the challenged claims unpatentable relying on the “snap-fit connection” of de Gennes as equivalent to the “fixing elements” of the ’614 patent. Sanofi appealed.

Discussion:

In its appeal, Sanofi argued that the PTAB “altered and extended Mylan’s deficient showing” by analyzing whether de Gennes constitutes analogous art to the ’614 patent when Mylan, the petitioner, only presented its arguments with respect to Burren (i.e. other prior art). Mylan countered that the Board had found de Gennes as analogous art because there was “no functional difference between the problem of Burren and the problem of the ‘614 patent.”

In its review of the law governing whether prior art is analogous, the CAFC noted that “we have consistently held that a patent challenger must compare the reference to the challenged patent” and, citing precedent, noted that the proper test is whether prior art is “reasonably pertinent to the particular problem with which the inventor is involved.” The CAFC expanded thereon stating:

Mylan’s arguments would allow a challenger to focus on the problems of alleged prior art references while ignoring the problems of the challenged patent. Even if a reference is analogous to one problem considered in another reference, it does not necessarily follow that the reference would be analogous to the problems of the challenged patent…[broad construction of analogous art]… does not allow a fact finder to focus on the problems contained in other prior art references to the exclusion of the problem of the challenged patent.

The Court re-emphasized that the petitioner has the burden of proving unpatentability and that they have reversed the Board’s patentability determination where a petitioner did not adequately present a motivation to combine.

Conclusion:

The CAFC concluded that the Board’s decision did not interpret Mylan’s obviousness argument as asserting de Gennes was analogous to the ’614 patent, but rather improperly relied on de Gennes being analogous to the primary reference, Burren. As such, Mylan did not meet its burden to establish obviousness premised on de Gennes; and therefore, the Board’s factual finding that de Gennes is analogous to the ’614 patent is unsupported by substantial evidence. The Court reversed the finding of obviousness.

Take away:

- Relying on non-analogous art to support an obviousness contention requires looking at the problems the inventor of the patent-in-issue would find pertinent not those set forth in other relied upon prior art. Arguments that a problem solved by non-analogous art should focus on the inventor of the patent-in-issue as recognizing the problem to be solved not generally problems recognized in the art.

- Petitioner’s in IPRs should be cautious relying on the PTAB formulating an argument outside of those clearly set forth in their filings. Extrapolation of Petitioner’s arguments by the PTAB can open the possibility of a reversal based on lack of substantial evidence.

Limitations of Result-Based Functional Language and Generic Computer Components in Patent Eligibility

| May 2, 2023

Hawk Technology Systems, Llc V. Castle Retail, LLC

Before REYNA, HUGHES, and CUNNINGHAM, Circuit Judges.

Summary

The district court granted Castle Retail’s motion, finding that the patent claims were directed towards the abstract idea of storing and displaying video without providing an inventive step to transform the abstract idea into a patent-eligible invention. The district court dismissed Hawk’s case, and Hawk appealed. The Federal Circuit upheld the district court’s decision, affirming that the patent claims were invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

Background

Hawk Technology Systems is the owner of a US Patent No. 10,499,091 ( the ’91 patent) entitled “High-Quality, Reduced Data Rate Streaming Video Product and Monitoring System.” The patent was filed in 2017 and granted in 2019, with priority claimed back to 2002. It describes a technique for displaying multiple stored video images on a remote viewing device in a video surveillance system, using a configuration that utilizes existing broadband infrastructure and a generic PC-based server to transmit signals from cameras as streaming sources at low data rates and variable frame rates. The patent claims that this approach reduces costs, minimizes memory storage requirements, and enhances bandwidth efficiency.

Hawk Technology Systems sued Castle Retail for patent infringement in Tennessee, alleging that Castle Retail’s use of security surveillance video operations in its grocery stores infringed on Hawk’s patent. Castle Retail moved to dismiss the case, arguing that the patent claims were invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 101, as they were directed towards ineligible subject matter.

The ‘091 patent contains six claims, but the appellant, Hawk Technology Systems, did not assert that there was any significant difference between the claims regarding eligibility. As a result, claim 1 was selected as representative, which recites:

1. A method of viewing, on a remote viewing device of a video surveillance system, multiple simultaneously displayed and stored video images, comprising the steps of:

receiving video images at a personal computer based system from a plurality of video sources, wherein each of the plurality of video sources comprises a camera of the video surveillance system;

digitizing any of the images not already in digital form using an analog-to-digital converter;

displaying one or more of the digitized images in separate windows on a personal computer based display device, using a first set of temporal and spatial parameters associated with each image in each window;

converting one or more of the video source images into a selected video format in a particular resolution, using a second set of temporal and spatial parameters associated with each image;

contemporaneously storing at least a subset of the converted images in a storage device in a network environment;

providing a communications link to allow an external viewing device to access the storage device;

receiving, from a remote viewing device remoted located remotely from the video surveillance system, a request to receive one or more specific streams of the video images;

transmitting, either directly from one or more of the plurality of video sources or from the storage device over the communication link to the remote viewing device, and in the selected video format in the particular resolution, the selected video format being a progressive video format which has a frame rate of less than substantially 24 frames per second using a third set of temporal and spatial parameters associated with each image, a version or versions of one or more of the video images to the remote viewing device, wherein the communication link traverses an external broadband connection between the remote computing device and the network environment; and

displaying only the one or more requested specific streams of the video images on the remote computing device.

In September 2021, the district court granted Castle Retail’s motion to dismiss the case. The court found that the claims in Hawk’s ‘091 patent failed the two-part Alice test. The court determined that the ‘091 patent is directed to an abstract idea of a method for storing and displaying video, and that the claimed elements are generic computer elements without any technological improvement.

Hawk’s argument that the temporal and spatial parameters are the inventive concept was also rejected, as the claims and specification failed to explain what those parameters are or how they should be manipulated. The district court also found that the claimed “analog-to-digital converter” and “personal computer based system” were not technological improvements, but rather generic computer elements. Additionally, it determined that the “parameters and frame rate” defined in the claims and specification did not appear to be more than manipulating data in a way that has been found to be abstract.

The district court concluded that the claims can be implemented using off-the-shelf, conventional computer technology and entered judgment against Hawk. Hawk appealed the decision.

Discussion

The Federal Circuit applied Alice step one in this case to determine if the ’091 patent claims were directed to an abstract idea. They agreed with the district court’s conclusion that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of “storing and displaying video.”

The Federal Circuit further clarified that the claims are directed to a method of receiving, displaying, converting, storing, and transmitting digital video “using result-based functional language.” Two-Way Media Ltd. v. Comcast Cable Commc’ns, LLC, 874 F.3d 1329, 1337 (Fed. Cir. 2017). The claims require various functional results of “receiving video images,” “digitizing any of the images not already in digital form,” “displaying one or more of the digitized images,” “converting one or more of the video source images into a selected video format,” “storing at least a subset of the converted images,” “providing a communications link,” “receiving . . . a request to receive one or more specific streams of the video images,” “transmitting . . . a version of one or more of the video images,” and “displaying only the one or more requested specific streams of the video images.”

Hawk argued that the ’091 patent claims were not directed to an abstract idea but to a specific technical problem and solution related to maintaining full-bandwidth resolution while providing professional quality editing and manipulation of digital video images. However, this argument failed because the Federal Circuit found that the claims themselves did not disclose how the alleged goal was achieved and that converting information from one format to another is an abstract idea. Furthermore, the claims did not recite a specific solution to make the alleged improvement concrete and, at most, recited abstract data manipulation. Therefore, the ’091 patent claims lacked sufficient recitation of how the purported invention improved the functionality of video surveillance systems and amounted to a mere implementation of an abstract idea.

At Alice step two, the claim elements were examined individually and as a combination to determine if they transformed the claim into a patent-eligible application of the abstract idea. The district court found that the claims did not show a technological improvement in video storage and display and that the limitations could be implemented using generic computer elements.

Hawk argued that the claims provided an inventive solution that achieved the benefit of transmitting the same digital image to different devices for different purposes while using the same bandwidth, citing specific tools, parameters, and frame rates. The Federal Circuit acknowledged that the claims mentioned “parameters.” However, the claims did not specify what these parameters were, and at most they pertained to abstract data manipulation such as image formatting and compression. Hawk did not contest that the claims involved conventional components to carry out the method. The Federal Circuit also noted that the ‘091 patent affirmed that the invention was meant to “utilize” existing broadband media and other conventional technologies. Thus, the Federal Circuit found that there is nothing inventive in the ordered combination of the claim limitations and noted that Hawk has not pointed to anything inventive.

The Federal Circuit determined that the claims in the ‘091 patent did not transform the abstract concept into something substantial and therefore did not pass the second step of the Alice test. As a result, the Federal Circuit concluded that the ‘091 patent is ineligible since its claims address an abstract idea that was not transformed into eligible subject matter.

Takeaway

- Reciting an abstract idea performed on a set of generic computer components does not contain an inventive concept.

- Claims that use result-based functional language in combination with generic computer components may not be sufficient to transform an abstract idea into patent-eligible subject matter.

A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words in Establishing Public Use When Utility is Ornamental

| April 3, 2023

In re WinGen LLC

Decided: February 2, 2023

Before Lourie, Taranto, and Stoll (Opinion by Lourie)

Summary

After reading this nonprecedential decision, one may wonder why it was not designated precedential, in view of quotes from the decision such as “what is necessary for an invalidating prior public use of a plant has not been considered by this court” and “This case therefore presents a unique question.” Nonetheless, a number of very interesting topics are raised regarding different ways to secure patent protection (a plant patent and/or a utility patent), and what may be considered an invalidating public use. This decision becomes more interesting when exploring the background of the patent in question which was not discussed in the decision, namely, why was a reissue pursued in the first place. Based on the author’s opinion, the reissue application may have become necessary due to a misunderstanding of the invention by both the Examiner and the prosecuting attorney.

Background

U.S. Patent No. 9,313,959 is directed to a Calibrachoa plant. Claim 1 is representative:

1. A Calibrachoa plant comprising at least one inflorescence with a radially symmetric pattern along the center of the fused petal margins, wherein said pattern extends from the center of the inflorescence and does not fade during the life of the inflorescence,

and wherein the Calibrachoa plant comprises a single half-dominant gene, as found in Calibrachoa variety ‘Cherry Star,’ representative seed having been deposited under ATCC Accession No. PTA-13363.

Reissue Application 15/229,819 was filed as a broadening reissue to delete “representative seed having been deposited under ATCC Accession No. PTA-13363”.[1] During prosecution of the reissue application, a final rejection was made that included rejections for lack of written description, nonstatutory double patenting, lack of enablement, and prior public use. On appeal to the Board, the Board reversed all the rejections except for the prior public use rejections. The Board found that a display of ‘Cherry Star’ had been accessible to the public at an event at The Home Depot. This event was hosted by Proven Winners North America LLC, a common shareholder with the original assignee of the ‘959 patent, Plant 21 LLC. Proven Winners is a brand management and marketing entity. Plant 21 entrusted Proven Winners with samples of ‘Cherry Star’ to show at a private event at The Home Depot. At the event, the attendees were not permitted to take cuttings, seeds, or tissue samples of the plant. However, the attendees were provided with a leaflet to bring home that included a photograph and brief description of the plant. In addition, the visitors were under no obligations of confidentiality. The visitors were not provided with any gene or breeding information regarding ‘Cherry Star’. The handout is shown below:

The Board’s decision also commented that it was undisputed that a complete invention comprising all the claimed characteristics[2] was on display at The Home Depot event.

WinGen appealed to the CAFC, arguing that the Board erred in finding prior public use when all the claimed features were not made available to the public. In particular, the attendees would not have been aware of or able to readily ascertain that ‘Cherry Star’ resulted from a “single half dominant gene”, and thus the display was not an invalidating prior public use.

Discussion

Under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(b), an applicant may not receive a patent for an invention that was in public use “more than one year prior to the date of application in the United States.” To determine an invalidating public use, the court considers whether the purported use (1) was accessible to the public or (2) was commercially exploited. Here, the CAFC commented that there was only one prior case involving prior public use of a plant (Delano Farms v. Cal. Table Grape Comm’n, 778 F.3d 1243 (Fed. Cir. 2015). That case involved the unauthorized growing of the claimed grapes in locations visible from public roads. Although the grapes were viewable to the public, they were not labeled in any way and there was no evidence that anyone recognized the grapes as the claimed varietal.

The CAFC distinguished this prior case from what occurred at The Home Depot event. At the event, ‘Cherry Star’ was indisputably identified. Although the handout itself was not a public use, the leaflet confirms that the physical plant on display was in fact ‘Cherry Star’.

The CAFC further commented that the use of ‘Cherry Star’ is purely ornamental, in contrast to the grapes in Delano Farms.

The CAFC noted that this case presents a unique question with respect to a purpose of ornament than other decisions regarding alleged public uses. For example, in Motionless Keyboard Co. v. Microsoft Corp., 486 F.3d 1376 (Fed. Cir. 2007), there was no evidence showing the invention was used for its intended purpose (visual display of a keyboard did not constitute public use because it was not connected to a computer or other device).

Although this all makes sense, whatever happened to WinGen’s argument regarding the claimed genetics (“comprises a single half-dominant gene”)? The CAFC dismissed this argument as WinGen “did not meaningfully present such an argument to the Board. We agree with the Director that such an argument was forfeited.” Had such an argument been made, it is likely there would have been a different outcome.

Background Notes

I was curious why the reissue became necessary. I looked at the prosecution history of the original patent and noted several interesting things that occurred during prosecution. Prior to the first action, there were several third-party prior art submissions. This is indicative that there were competitors concerned about a utility patent issuing. One submission included a photograph of ‘Cherry Star’. This photograph was initially entered by the USPTO, but then later expunged after the patent applicant filed a petition. A subsequent third-party submission included another photograph from a publication describing ‘Cherry Star’ which was entered into the record.

The Examiner’s first office action included numerous rejections. An interview was conducted prior to filing a response which seemed productive in that the Examiner suggested amendment to include the semi-dominant gene as found in the deposited variety ‘Cherry Star’. However, there was also an objection made by the Examiner regarding the use of “tissue” in the specification instead of “seed” in reference to the biological material which was deposited. The applicant proceeded with the Examiner’s suggested amendment, but this may have been the mistake that led to the need for a reissue application. The original specification described that the plant is produced from tissue having been deposited. The use of “tissue” seems to have meant the genetic material as opposed to seeds. As described in the specification:

Additionally, and as known in the art, Calibrachoa plants can be reproduced asexually by vegetative propagation or other clonal method known in the art. For example, and in no way limiting, a Calibrachoa plant having at least one inflorescence with a radially symmetric pattern along the center of the fused petal margins, can be reproduced by (a) obtaining a tissue cutting from said plant, (b) culturing said tissue cutting under conditions sufficient to produce a plantlet with roots and shoots; and (c) growing said plantlet to produce a plant,

In other words, the plants themselves are asexually reproduced. Growing plants from the seeds may not produce the claimed plant.

[1] Observed by the author from the image file wrapper of the reissue application.

[2] This admission or lack of dispute proves detrimental to the patentee.

A Claim term referring to an antecedent using “said” or “the” cannot be independent from the antecedent

| February 24, 2023

Infernal Technology, LLC v. Activision Blizzard Inc.

Decided: January 24, 2023

Moore, Chen, Stoll. Opinion by Chen.

Summary:

Infernal sued Activision for infringement of its patents to lighting and shadowing methods for use with computer graphics based on nineteen Activision video games. Based on the construction of the claim term “said observer data,” Activision filed a motion for summary judgment of non-infringement. The CAFC agreed with the District Court’s analysis of the noted claim term and affirmed the motion for summary judgment of non-infringement.

Details:

Infernal owns the related U.S. Patent Nos. 6,362,822 and 7,061,488 to “Lighting and Shadowing Methods and Arrangements for Use in Computer Graphic Simulations” providing methods of improving how light and shadow are displayed in computer graphics. Claim 1 of the ‘822 patent is provided:

1. A shadow rendering method for use in a computer system, the method comprising the steps of:

[1(a)] providing observer data of a simulated multi-dimensional scene;

[1(b)] providing lighting data associated with a plurality of simulated light sources arranged to illuminate said scene, said lighting data including light image data;

[1(c)] for each of said plurality of light sources, comparing at least a portion of said observer data with at least a portion of said lighting data to determine if a modeled point within said scene is illuminated by said light source and storing at least a portion of said light image data associated with said point and said light source in a light accumulation buffer; and then

[1(d)] combining at least a portion of said light accumulation buffer with said observer data; and

[1(e)] displaying resulting image data to a computer screen.

(Emphasis added).

The parties agreed to the construction of the term “observer data” as meaning “data representing at least the color of objects in a simulated multi-dimensional scene as viewed from an observer’s perspective.” The district court adopted this construction. Based on this construction and the plain and ordinary meaning of the limitation “said observer data” in step 1(d), Activision filed a motion for summary judgment of non-infringement, and the district court granted the summary judgment.

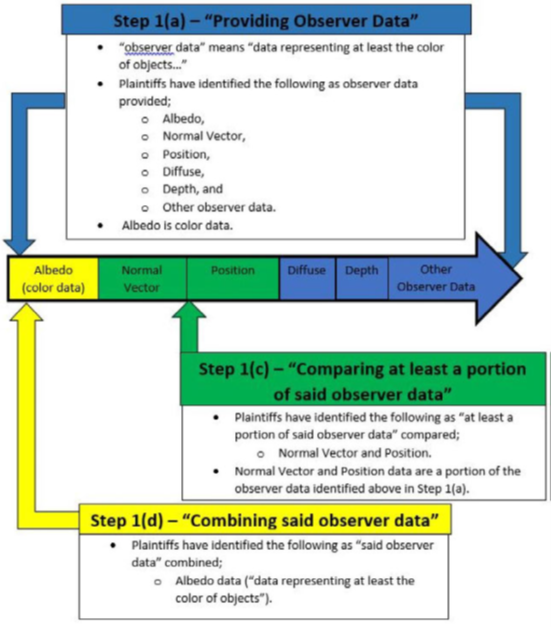

On appeal, Infernal argued that the district court misapplied its own construction of “observer data.” Infernal argued that “observer data” can refer to different data sets in steps 1(a), 1(c) and 1(d), each different data set independently satisfying the “observer data” construction. Step 1(a) recites “providing observer data,” step 1(c) recites “comparing at least a portion of said observer data,” and step 1(d) recites “combining … with said observer data.” The reason Infernal applies this construction is due to their infringement theory summarized below:

In its infringement theory, for step 1(a) Infernal refers to albedo (color data), normal vector, position, diffuse, depth, and other observer data; for step 1(c), Infernal refers to normal vector and position data; and for step 1(d), Infernal refers to only albedo data. Thus, Infernal’s infringement theory relies on applying different obverser data for steps 1(a), 1(c) and 1(d). Infernal argued that “said observer data” in step 1(d) can refer to a narrower set of data than “observer data” in step 1(a) because both independently meet the district court’s construction of “observer data.”

In analyzing Infernal’s argument, the CAFC stated the principal that “[in] grammatical terms, the instances of [‘said’] in the claim are anaphoric phrases, referring to the initial antecedent phrase” citing Baldwin Graphic Sys., Inc. v. Siebert, Inc., 512 F.3d 1338, 1342 (Fed. Cir. 2008). The CAFC further stated that based on this principle, the term “said observer data” recited in steps 1(c) and 1(d) must refer back to the “observer data” recited in step 1(a), and concluded that “the ‘observer data’ in step 1(a) must be the same “observer data” in steps 1(c) and 1(d).” The CAFC stated that this analysis applies even though the district court’s construction of “observer data” encompasses “at least color data.” In concluding that term “observer data” cannot refer to different data among steps 1(a), 1(c) and 1(d), the CAFC stated:

Although the initial “observer data” in step 1(a) includes data that is “at least color data,” the use of the word “said” indicates that each subsequent instance of “said observer data” must refer back to the same “observer data” initially referred to in step 1(a). An open-ended construction of “observer data” (“data representing at least the color of objects”) does not permit each instance of “observer data” in a claim to refer to an independent set of data.

Regarding the district court’s finding that Infernal failed to raise a genuine issue of material fact, Infernal argued that the district court erred in its finding that the accused video games cannot perform the claimed steps in the specified sequence. The district court held that Infernal failed to raise a genuine issue of material fact as to the accused games performing limitation 1(d): “combining … with said observer data.”

The CAFC agreed with the district court. Referring to Infernal’s infringement theory diagram, the CAFC stated that for step 1(a), Infernal identified “observer data” as albedo (color data), normal vector, position, diffuse, depth, and other observer data, but for step 1(d), Infernal identified “said observer data” as only albedo (color data). “Because it is undisputed that the mapping of the Accused Games’s ‘observer data’ in step 1(a) is different than the mapping of the “observer data” in step 1(d), … there is no genuine issue of material fact as to whether the Accused Games infringe [step 1(d)].” The CAFC also pointed out that Infernal’s mapping for step 1(d) improperly excludes data that is mapped to “a portion of said observer data” in step 1(c).

Comments

In a footnote, the CAFC stated that this analysis is consistent with other cases in which the use of the word “said” or “the” refers back to the initial limitation, “even when the initial limitation refers to one or more elements.” When drafting claims, if you intend for a later recitation of the same limitation to refer to an independent instance of the limitation, then you will need to modify the language rather than merely using “said” or “the.”

It appears that if step 1(d) in Infernal’s claim referred to “at least a portion of said observer data,” Infernal would have had a better argument that the observer data in step 1(d) can be a narrower data set than the “observer data” in step 1(a). The CAFC also pointed out that Infernal knew how to do this because that is what they did in step 1(c) and chose not to in step 1(d).

Obvious Claim Limitation Fails to Present Different Issues of Patentability Needed to Deny Collateral Estoppel

| February 16, 2023

Google LLC V. Hammond Development International, Inc.

Decided: December 8, 2022

Moore, Chen, and Stoll. Opinion by Moore.

Summary

On appeal from an inter partes review (IPR) decision finding some claims of a first patent not unpatentable over prior art, where counterpart claims of a related, second patent had been invalidated in another IPR decision, the CAFC found that the second IPR decision has collateral estoppel effect on certain challenged claims of the first patent where slight difference in claim language immaterial to the question of validity in the underlying decision does not present different issues of patentability.

Details

Google filed IPR petitions against Hammond’s patents including U.S. Patent Nos. 10,270,816 (“’816 patent”) and No. 9,264,483 (“’483 patent”). Hammond’s challenged patents relate to a communication system that allows a communication device to remotely execute one or more applications. The specification shared by these patents discloses that the inventive system enables a user to check a bank account balance or airline flight status by using a cell phone or other communication devices to interact with application servers over a network, which in turn access database storing applications so as to perform the desired functionalities. As seen in Figs. 1A-1D, for example, the system may be implemented using a single application server or multiple application servers.

In the ‘816 IPR, Google challenged all the claims of the patent, asserting different prior art combinations against different subsets of claims. Relevant to this case are obviousness challenges of claims 1, 14 and 18 which recite, among other things, one or both of two particular limitations referred to as first[1] and second[2] “request for processing service” limitations, as summarized below:

| Claims | “request for processing service” limitations recited | References/Basis |

| Independent claim 1 | Both first and second limitations | Gilmore, Dhara, and Dodrill |

| Independent claim 14 | First limitation | Gilmore and Creamer |

| Claim 18 dependent from claim 14 | Second limitation | Gilmore, Creamer and Dodrill |

As to claim 1, Google asserted that Gilmore and Dodrill in combination would meet the first and second limitations. As to claim 14, however, Google did not rely on Dodrill for the first limitation in particular. Instead, Google included Dodrill solely to obviate the second limitation as recited in claim 18 dependent from claim 14.

The above choice of references caused trouble to Google. The Board, finding Gilmore and Dodrill in combination as teaching both the first and second limitations in claim 1, determined that the combination of Gilmore and Creamer would not do so with the first limitation as recited in claim 14. Further, Google’s assertion of invalidity as to dependent claim 18 also failed with the contrary finding of claim 14; even though Google did rely on Dodrill for the second limitation as recited in claim 18, that reliance did not extend to the first limitation in parent claim 14. On June 4, 2021, a final written decision was issued in the ‘816 IPR, determining that claims 1–13 and 20–30 would have been obvious, but not claim 14 and its dependent claims 15–19.

On April 12, 2021, prior to the ‘816 IPR decision, the ‘483 IPR had concluded in a final written decision invalidating all the challenged claims for obviousness over prior art including Gilmore and Dodrill. Among those invalidated claims was claim 18 of the ‘483 patent, which recites both the first and second “request for processing service” limitations as in claim 18 of the ‘816 patent.

Google appealed the IPR rulings on claims 14-19 of the ‘816 patent to the CAFC. Google asserted, among other things, that collateral estoppel effect of the invalidity determination of claim 18 of the ‘483 patent renders claim 18 of the ‘816 patent also unpatentable. Finding collateral estoppel as applicable to this case, the CAFC reversed as to claims 14 and 18, and affirmed as to claims 15-17 and 19.

No forfeiture of collateral estoppel

As a preliminary matter, the CAFC found that Google’s omission of its collateral estoppel argument in the IPR petition does not cause forfeiture. Since the issuance and the finality of the ‘483 final written decision took place only after Google’s filing of the ‘816 IPR petition, the argument based on non-existent preclusive judgement could not have been included in that petition. As such, the CAFC held that Google is allowed to raise its collateral estoppel argument for the first time on appeal.

Collateral estoppel – Identicality requirement

Noting that the collateral estoppel can apply in IPR proceedings, the CAFC recited the four requirements for the preclusive effect to exist under In re Freeman:

(1) the issue is identical to one decided in the first action; (2) the issue was actually litigated in the first action; (3) resolution of the issue was essential to a final judgment in the first action; and (4) [the party against whom collateral estoppel is being asserted] had a full and fair opportunity to litigate the issue in the first action.

Only the first element was disputed in the present case. Citing its precedents, the CAFC emphasized that the identicality requirement concerns identicality of “the issues of patentability” (emphasis original), rather than the claim language per se. As such, applicability of collateral estoppel is not affected by mere existence of slightly different wording used to depict a substantially identical invention so long as the differences between the patent claims “do not materially alter the question of invalidity,” which is “a legal conclusion based on underlying facts.”

Claim 18 – Invalid for collateral estoppel

The CAFC held that collateral estoppel applies so as to render the claim 18 of the ‘816 patent unpatentable because it shares identical issues of patentability with the invalidated claim 18 of the ’483 patent. Specifically, the CAFC noted that “only difference between the claims is the language describing the number of application servers”: The claim 18 of the ‘816 patent recites “a plurality of application servers” including “first one” and “second one” configured to perform certain respective functions specifically associated therewith, whereas the claim 18 of the ‘483 patent requires “one or more application servers” or “the at least one application server” to perform the requisite functionality. The CAFC found that the difference is immaterial to the question of invalidity in the collateral estoppel analysis, relying on the Board’s factual findings that the above limitation of claim 18 of the ‘816 patent would have been obvious to a skilled artisan, as supported by Google’s expert evidence, which were not challenged by Hammond on appeal.

Claim 14 – Invalid for invalidation of dependent claim 18

Having found claim 18 unpatentable, the CAFC went on to hold that independent claim 14, from which claim 18 depends, is also unpatentable. In so doing, the CAFC noted that the parties had agreed on the invalidity consequence of the parent claim based on the invalidated dependent claim[3]. In a footnote, the Opinion states that since Hammond failed to assert that Google’s collateral estoppel arguments should be limited to the references asserted in the petition, the impact of Google’s original invalidity challenge against claim 14—which does not use the same combination of references as claim 18—was not explored.

Claims 15-17 and 19 – Not unpatentable due to lack of collateral estoppel arguments

The CAFC distinguished the remaining claims from claim 18 and claim 14. Unlike claim 18, Google made no collateral estoppel arguments against claims 15-17 and 19. Rather, Google’s arguments as to these claims relied on the Board’s obviousness findings as to parallel dependent claims. Moreover, unlike claim 14, Hammad did not admit that invalidity of claim 18 is consequential to unpatentability of claims 15-17 and 19. As such, Google failed to meet its burden to provide convincing arguments for reversal on appeal.

Takeaway

This case depicts an interplay between collateral estoppel analysis on appeal and obviousness findings in underlying litigation: The identicality of the issues of patentability exists where the adjudicated and the unadjudicated claims are substantially the same with their only difference being a limitation that has been found as obvious. Parties in parallel actions involving patent claims of the same family may want to be mindful of potential impact of obviousness determination as to a claim limitation unique to one patent but not in the other in the future inquiry of collateral estoppel.

[1] Recited as “the application server is configured to transmit … a request for processing service … to the at least one communication device” in claim 1 of the ‘816 patent.

[2] Recited as “wherein the request for processing service comprises an instruction to present a user of the at least one communication device the voice representation” in claim 1 of the ‘816 patent.

[3] “[T]he patentability of claim 14 rises and falls with claim 18.” During oral argument, this principle was noted referring to Callaway Golf Co. v. Acushnet Co. (Fed. Cir., August 14, 2009).

« Previous Page — Next Page »