FUNCTIONAL CLAIMS REQUIRE MORE THAN JUST TRIAL-AND-ERROR INSTRUCTIONS FOR SATISFYING THE ENABLEMENT REQUIREMENT

| January 5, 2024

Baxalta Inc. v. Genentech, Inc.

Decided: September 20, 2023

Moore, Clevenger and Chen. Opinion by Moore

Summary:

Baxalta sued Genentech alleging that Genentech’s Hemlibra product infringes US Patent No. 7,033,590 (the ‘590 patent). Genentech moved for summary judgment of invalidity of the claims for lack of enablement. The district court granted summary judgment of invalidity. Upon appeal to the CAFC, the CAFC affirmed invalidity for lack of enablement citing the recent Supreme Court case Amgen v. Sanofi.

Details:

Baxalta’s patent is to a treatment for Hemophilia A. Blood clots are formed by a series of enzymatic activations known as the coagulation cascade. In a step of the cascade, enzyme activated Factor VIII (Factor VIIIa) complexes with enzyme activated Factor IX (Factor IXa) to activate Factor X. Hemophilia A causes the activity of Factor VIII to be functionally absent which impedes the coagulation cascade and the body’s ability to form blood clots. Traditional treatment includes administering Factor VIII intravenously. But this treatment does not work for about 20-30% of patients.

The ‘590 patent provides an alternative treatment. The treatment includes antibodies that bind to Factor IX/IXa to increase the procoagulant activity of Factor IXa which allows Factor IXa to activate Factor X in the absence of Factor VIII/VIIIa. Claim 1 of the ‘590 patent is provided:

1. An isolated antibody or antibody fragment thereof that binds Factor IX or Factor IXa and increases the procoagulant activity of Factor IXa.

The ‘590 patent describes that the inventors performed four hybridoma fusion experiments using a prior art method. And using routine techniques, the inventors screened the candidate antibodies from the four fusion experiments to determine whether the antibodies bind to Factor IX/IXa and increase procoagulant activity as claimed. Only 1.6% of the thousands of screened antibodies increased the procoagulant activity of Factor IXa. The ‘590 patent discloses the amino acid sequences of eleven antibodies that bind to Factor IX/IXa and increase the procoagulant activity of Factor IXa.

Citing Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi, 598 U.S. 594 (2023), the CAFC stated that “the specification must enable the full scope of the invention as defined by its claims, allowing for a reasonable amount of experimentation. Citing additional cases, the CAFC stated “in other words, the specification of a patent must teach those skilled in the art how to make and use the full scope of the claimed invention without undue experimentation.”

Baxalta argued that one of ordinary skill in the art can obtain the full scope of the claimed antibodies without undue experimentation because the patent describes the routine hybridoma-and-screening process. However, the CAFC stated that the facts of this case are indistinguishable from the Amgen case in which the patent at issue provided two methods for determining antibodies within the scope of the claims. In Amgen, the Supreme Court stated that the two disclosed methods were “little more than two research assignments,” and thus, the claims fail the enablement requirement.

The CAFC described the claims in this case as covering all antibodies that (1) bind to Factor IX/IXa; and (2) increase the procoagulant activity of Factor IXa, and that “there are millions of potential candidate antibodies.” The specification only discloses amino acid sequences for eleven antibodies within the scope of the claims. Regarding the method for obtaining the claimed antibodies, the specification describes the following steps:

(1) immunize mice with human Factor IX/IXa;

(2) form hybridomas from the antibody-secreting spleen cells of those mice;

(3) test those antibodies to determine whether they bind to Factor IX/IXa; and

(4) test those antibodies that bind to Factor IX/IXa to determine whether any increase procoagulant activity.

The CAFC stated that similar to Amgen, this process “simply directs skilled artisans to engage in the same iterative, trial-and-error process the inventors followed to discover the eleven antibodies they elected to disclose.”

The Supreme Court in Amgen also stated that the methods for determining antibodies within the scope of the claims might be sufficient to enable the claims if the specification discloses “a quality common to every functional embodiment.” However, no such common quality was found in the ‘590 patent that would allow a skilled artisan to predict which antibodies will perform the claimed functions. Thus, the CAFC concluded that the disclosed instructions for obtaining claimed antibodies, without more, “is not enough to enable the broad functional genus claims at issue here.”

Baxalta further argued that its process disclosed in the ‘590 patent does not require trial-and-error because the process predictably and reliably generates new claimed antibodies every time it is performed. The CAFC stated that even if a skilled artisan will generate at least one claimed antibody each time they follow the disclosed process, “this does not take the process out of the realm of the trial-and-error approaches rejected in Amgen.” “Under Amgen, such random trial-and-error discovery, without more, constitutes unreasonable experimentation that falls outside the bounds required by § 112(a).”

Baxalta also argued that the district court’s enablement determination is inconsistent with In re Wands. The CAFC disagreed stating that the facts of this case are more analogous to the facts in Amgen, and the Amgen case did not disturb prior enablement case law including In re Wands and its factors.

Comments

When claiming a product functionally, make sure your specification includes something more than just trial-and-error instructions. The CAFC suggested in this case that the enablement requirement may be satisfied if the patent discloses a common structural or other feature delineating products that satisfy the claims from products that will not. The CAFC also suggested that a description about why the actual disclosed products perform the claimed functions or why other products do not perform the claimed function would be helpful for satisfying the enablement requirement.

Ramification of Silence in Prosecution History and Reminder on Formulating Effective Obviousness Arguments

| November 17, 2023

ELEKTA LIMITED v. ZAP SURGICAL SYSTEMS, INC.

Decided: September 21, 2023

Before Reyna, Stoll, and Stark. Opinion by Reyna.

Summary

The CAFC held that motivation to combine references is supported by substantial evidence including the patent prosecution history where relevancy of certain prior art, similar to an asserted reference in the IPR, was not contested by the applicant. The CAFC also rejected the patent owner’s arguments on lack of requisite findings on reasonable expectation of success, where such findings can be implied from express findings on motivation to combine as the two issues are interrelated to each other.

Details

Elekta’s U.S. Patent No. 7,295,648 (the “’648 patent”) pertains to ionizing radiation treatment. The technology is designed to deliver therapeutic radiation, such as one created by a linear accelerator or “linac,” to a target area of a patient such as brain tumors for treatment purposes. The ‘648 patent discloses that the linac, because of its great weight, requires a suitable structure to support the device while allowing a wide range of movement to focus the radiation precisely, leading to a challenge in implementing the linac-based system for treating highly sensitive, complex areas as with neurosurgery.

Representative claim 1 of the ‘648 patent recites:

A device for treating a patient with ionising radiation comprising:

a ring-shaped support, on which is provided a mount,

a radiation source attached to the mount;

the support being rotateable about an axis coincident with the centre of the ring;

the source being attached to the mount via a rotateable union having a an axis of rotation axis which is non-parallel to the support axis;

wherein the rotation axis of the mount passes through the support axis of the support and the radiation source is collimated so as to produce a beam which passes through the co-incidence of the rotation and support axes.

In the underlying inter partes review, the final written decision concluded, among other things, that claim 1 of the ’648 patent is obvious over a combination of Grady and Ruchala. In essence, Grady teaches an X-ray imaging device having a sophisticated rotatable support structure similar to that recited in the body of claim 1, whereas Ruchala teaches a linac-based radiation device for treating tumors, which may correspond to “treating a patient with ionising radiation” of claim 1.

On appeal, the CAFC addressed Elekta’s three main arguments regarding obviousness of claim 1: (1) “the Board’s findings on a motivation to combine are unsupported by substantial evidence”; (2) “the Board failed to make any findings, explicit or implicit, on a reasonable expectation of success”; and (3) “even had the Board made such findings, those findings are not supported by substantial evidence.” The CAFC reviewed the Board’s legal conclusions de novo and its factual findings for substantial evidence.

- Substantial evidence for the motivation to combine

Elekta argued that substantial evidence was lacking with the Board’s finding of a motivation to combine the references. In particular, Elekta asserted that no motivation would have existed for a skilled artisan to combine Grady and Ruchala, one disclosing “radiation imagery” and the other for “radiation therapy,” where incorporating Ruchala’s linac radiation into Grady’s imaging system would not improve its imagery function in any aspect, whilst the linac’s heavy weight would hamper precision and control, thereby “render[ing] the device essentially inoperable.”

The Board’s obviousness conclusion relies on, among other findings, its review of the prosecution of the ’648 patent, wherein “patents directed to imaging devices were cited, and were not distinguished based on an argument that imaging devices were not relevant art,” along with the pertinent field being framed in the IPR as one that “includes the engineering design of sturdy mechanical apparatus[es] capable of rotationally manipulating heavy devices in three dimensions oriented in a variety of approach angles with high geometrical accuracy, in the context of the radiation imaging and radiation therapy environment.”

The CAFC held that there was substantial evidence for the motivation to combine. Specifically, the CAFC noted that such evidence includes the prosecution history of the ’648 patent, in which Elekta “notably did not argue that prior art references directed to imaging devices were not relevant art.” The CAFC concluded that such failure to distinguish imaging radiation prior art during the patent prosecution, along with the asserted references and an expert testimony pointing to benefits of combining imagery and therapeutic radiation functions, substantially support the motivation to combine.

- Findings on the reasonable expectation of success

Elekta argued that the Board’s obviousness determination was devoid of any findings on reasonable expectation of success.

The CAFC disagreed, finding that a sufficient, implicit finding was made as to the reasonable expectation of success. The CAFC contrasted findings of reasonable expectation of success, which “can be implicit,” with those of motivation to combine, which must be “explicit.” Although an explicit finding would be usually required to support determinations made by the Board, the CAFC points to its precedent where the Board’s rejection of a patent owner’s motivation to combine argument based on teaching away constituted an implicit finding of a reasonable expectation of success, as the latter could be “reasonably discern[ed]” in the Board’s findings on “other, intertwined arguments.”

The CAFC noted that Elekta’s own arguments on the motivation to combine and the reasonable expectation of success presented before the Board were “blended”: Elekta essentially asserted that the suggested combination, lacking precision and control due to the device’s heavy weight, would fail to serve its intended purposes so as to negate motivation to combine, and consequently, would also negate reasonable expectation of success. As such, the CAFC held that by making express findings on the motivation to combine, the Board adequately made an implicit finding on Elekta’s argument on reasonable expectation of success.

- Substantial evidence for the reasonable expectation of success

Elekta argued that substantial evidence was lacking in the Board’s findings, if any, on reasonable expectation of success.

The CAFC succinctly rejected the argument. The CAFC noted that the evidence establishing a motivation to combine may—but not always—establish a finding of reasonable expectation of success. And that was the case with the present appeal, where “the arguments and evidence of reasonable expectation of success are the same for motivation to combine.”

Takeaways

This case presents an interesting situation pointing to one potential ramification of prosecution history made by silence: A failure to object to the scope of pertinent art during patent prosecution undercuts the patent owner’s argument in attacking the motivation to combine, where the asserted prior art is arguably from a disparate field. It is important to consider potential benefits and downsides of presenting or not presenting certain arguments during prosecution.

Another takeaway is the importance of formulating non-obviousness arguments on an issue-by-issue basis even if interrelated issues are involved; doing so would help keep the analysis of reasonable expectation of success from being comingled with the issues of motivation to combine.

Tags: motivation to combine > prosecution history > Reasonable Expectation of Success

IPR Amendments: Broader is Broader (even narrowly so).

| September 15, 2023

Sisvel International S.A. v. Sierra Wireless, Inc, Telit Cinterion Deuschland GMBH

Decided: September 1, 2023

Before Prost, Reyna and Stark. Authored by Stark.

Summary: Sisvel appealed a PTAB IPR decision based on claim construction and denial of entry of a claim amendment for broadening the claim. The CAFC affirmed the Board on both counts, noting that broad disclosures in the specification will lead to a broad interpretation of the claims, and that claim amendments which encompass embodiments that would come within the scope of the amended claim but would not have infringed the original claim will be considered broadening.

Background:

In an IPR involving Sisvel’s patent claims 10, 11, 13, 17, and 24 of U.S. Patent No. 7,433,698 (the “’698 patent”) and claims 1, 2, 4, and 13-18 of U.S. Patent No. 8,364,196 (the “’196 patent”), the PTAB had found all claims unpatentable as anticipated and/or obvious in view of certain prior art.

The issues centered on the phraseology in the claims regarding the “connection rejection message” being used to direct a mobile communication means to attempt a new connection with certain parameter values such as a certain carrier frequency.

Claim 10, reproduced below, was the primary representative claim used by the CAFC:

10. A channel reselection method in a mobile communication means of a cellular telecommunication system, the method comprising the steps of:

receiving a connection rejection message;

observing at least one parameter of said connection rejection message; and

setting a value of at least one parameter for a new connection setup attempt based at least in part on information in at least one frequency parameter of said connection rejection message.

On appeal, Sisvel challenged the Board’s construction of the single claim term, “connection rejection message.”

Sisvel also challenged the Board’s denial of their motion to amend the claims on the basis that the amendment enlarged their scope.

Decision:

(a) Claim construction of “connection rejection message”

Sisvel appealed the Board’s construction of giving “connection rejection message” its plain and ordinary meaning of “a message that rejects a connection.” Sisvel’s purported a construction of “a message from a GSM or UMTS telecommunications network rejecting a connection request from a mobile station.” However, the PTAB found that such a construction would improperly limit the claims to embodiments using a Global System for Mobile Communication (“GSM”) or Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (“UMTS”) network.

Sisvel argued that UMTS and GSM “are the only specific networks identified by [the] ’698 and ’196 patents that actually send connection rejection messages” provided for in their specification.

The CAFC, in required fashion, reiterated the Phillips claim-construction standard – whereby “[t]he words of a claim are generally given their ordinary and customary meaning as understood by a person of ordinary skill in the art when read in the context of the specification and prosecution history,” citing Thorner v. Sony Comput. Ent. Am. LLC, 669 F.3d 1362, 1365 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (citing Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303, 1313 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (en banc)) 669 F.3d at 1365.

After reviewing, the Court found that the intrinsic evidence provided no persuasive basis to limit the claims to any particular cellular networks. They noted that the specification, while only expressly disclosing embodiments in a UMTS or GSM network, in fact still included broad teachings directed to any network. The CAFC affirmed the Board, noting that a person of ordinary skill in the art would not read the broad claim language, accompanied by the broad specification statement to be limited to GSM and UMTS networks.

(b) IPR Amendment

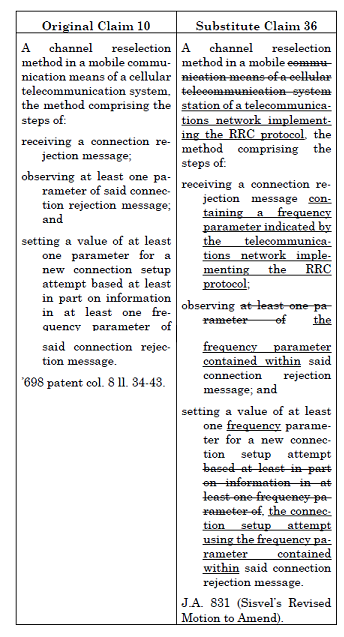

The Court also considered Sisvel’s contention that the Board erred during the IPR by denying its motion to amend the claims of the ’698 patent. The Board had denied Sisvel’s motion, concluding that the amendments to original claim 10 would have impermissibly enlarged claim scope. Original claim 10 and substitute amended claim 36 read as follows:

The Court first noted that broadening claims are not allowable during an IPR in the same fashion as in a Reissue or Reexamination proceeding at the USPTO. They further delved into the law of what constitutes a broadening of a claim noting that a claim “is broader in scope than the original claim if it contains within its scope any conceivable apparatus or process which would not have infringed the original patent” citing Hockerson-Halberstadt, Inc. v. Converse Inc., 183 F.3d 1369, 74 (Fed. Cir. 1999).

The Court further remarked that it is Sisvel’s burden, as the patent owner, to show that the proposed amendment complies with relevant regulatory and statutory requirements, citing to 37 C.F.R. § 42.121(d)(1) (“A patent owner bears the burden of persuasion to show, by a preponderance of the evidence, that the motion to amend complies with the [applicable] requirements . . . .”).

The PTAB’s denial had focused on the last (“setting a value”) limitation, comparing the original claim’s requirement that the value be set “based at least in part on information in at least one frequency parameter” of the connection rejection message, while in the substitute claims the value may be set merely by “using the frequency parameter” contained within the connection rejection message. The Board had concluded that “[i]n proposed substitute claim 36, the value that is set need not be based, in whole or in part, on information in the connection rejection message and, thus, claim 36 is broader in this respect than claim 10.” J.A. 73.

The Court agreed with the PTAB’s reasoning that, in the context of these claims, “using” is broader than “based on” and that whereas the original claim language required that the value in a new connection setup attempt be at least in some respect impacted by (i.e., “based” on) the frequency parameter, the substitute claim removes this requirement. They concluded that this removal of a claim requirement can broaden the resulting amended claim, because it is conceivable there could be embodiments that would come within the scope of substitute claim 36 but would not have infringed original claim 10, citing Pannu v. Storz Instruments, Inc., 258 F.3d 1366, 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2001) (“A reissue claim that does not include a limitation present in the original patent claims is broader in that respect.”).

Take aways:

- The Phillips standard is reiterated with the Court finding that even general disclosures within a specification (i.e. not supported by any embodiments) will provide sufficient intrinsic evidence that a skilled artisan will be considered to interpret the claim language to encompass the general disclosures.

- Drafting claim amendments in a post-grant proceeding at the USPTO must be done with extreme care. Any logically conceivable interpretation of the amendment whereby embodiments would come within the scope of substitute claim but would not have infringed the original claim will be considered broadening.

Why not to be conclusory!

| September 6, 2023

Volvo Penta of the Ams. LLC v. Brunswick Corp.

Decided: August 24, 2023

Before Moore, Chief Judge, Lourie and Cunningham, Circuit Judges. Authored by Chief Judge, Lourie.

Summary:

The CAFC vacated a Final Written Decision of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) holding all claims of U.S. Patent 9,630,692 (the “’962 patent”), owned by Volvo Penta, unpatentable as obvious. The court remanded the decision for further evaluation of objective indicia of non-obviousness that the Board had not adequately considered.

- A steerable tractor-type drive for a boat, comprising:

a drive support mountable to a stern of the boat;

a drive housing pivotally attached to the support about a steering axis, the drive housing having a vertical drive shaft connected to drive a propeller shaft, the propeller shaft extending from a forward end of the drive housing;

at least one pulling propeller mounted to the propeller shaft,

wherein the steering axis is offset forward of the vertical drive shaft.

The ’962 patent is directed to a boat drive, designed to provide a “pulling-type” or “forward facing drive” positioned under the stern of the boat. Claim 1 of the ’692 patent, reproduced below, is representative.

In 2015, Volvo Penta launched its commercial embodiment of the ’692 patent, the ‘Forward Drive.’ This product became extremely successful once available, particularly for wakesurfing and other water sports.

In August 2020, Brunswick Corp. (“Brunswick”) launched its own drive that also embodied the ’692 patent, the ‘Bravo Four S.’ The same day that Brunswick launched the Bravo Four S, it petitioned for inter partes review of all claims of the ’692 patent. Relevant to this appeal, Brunswick asserted that the challenged claims would have been obvious based on the references, Kiekhaefer and Brandt. Kiekhaefer is a 1952 patent assigned to Brunswick and directed to an outboard motor that could have either rear-facing or forward-facing propellers. Brandt is a 1989 patent assigned to Volvo Penta and directed to a stern drive with rear-facing propellers.

Volvo Penta position was not that the references combined failed to disclose all the claim elements, but rather that there was a lack of motivation to combine said references. Volvo Penta further proffered evidence of six objective indicia of non-obviousness: copying, industry praise, commercial success, skepticism, failure of others, and long-felt but unsolved need.

Ultimately, the Board had found Volvo Penta’s position unpersuasive asserting that sufficient motivation was found and that Volvo Penta’s objective evidence of secondary considerations was insufficient to outweigh Brunswick’s “strong evidence of obviousness.”

Accordingly, Volvo Penta raises three main arguments on appeal: (1) that the Board’s finding of motivation to combine was not supported by substantial evidence, (2) that the Board erred in its determination that there was no nexus, and (3) that the Board erred in its consideration of Volvo Penta’s objective evidence of secondary considerations of nonobviousness.

The court discussed each one in turn:

- Motivation:

The court began:

The ultimate conclusion of obviousness is a legal determination based on underlying factual findings, including whether or not a relevant artisan would have had a motivation to combine references in the way required to achieve the claimed invention. Henny Penny Corp. v. Frymaster LLC, 938 F.3d 1324, 1331 (Fed. Cir. 2019) (citing Wyers v. Master Lock Co., 616 F.3d 1231, 1238–39 (Fed. Cir. 2010)).

Volvo Penta first argued that the Board ignored a number of assertions in its favor, including: (1) that Brunswick, despite having knowledge of Kiekhaefer for decades, never attempted the proposed modification itself; (2) that Brunswick’s proposed modification would have entailed a nearly total and exceedingly complex redesign of the drive system; (3) the complexity of and difficulty in shifting the vertical drive shaft of Kiekhaefer; and (4) that Brunswick itself attempted to make its proposed modification yet failed to create a functional drive. The court disagreed on all points.

The Board acknowledged the testimony of Volvo Penta’s expert that a “complete redesign of Brandt” would be necessary, including “over two dozen modifications,” but ultimately found that not all of the identified changes would have been required to arrive at the claimed invention.

Volvo Penta also argued that the Board’s reliance on Kiekhaefer for motivation to combine was misplaced. The Board had relied on Kiekhaefer teaching that a “tractor-type propeller” is “more efficient and capable of higher speeds.” Volvo Penta argued this is not the metric by which recreational boats are measured.

However, again, the court disagreed stating that while ‘it is likewise not conclusive that speed may not be the primary or only metric by which recreational boats are measured. Substantial evidence supports a finding that speed is at least a consideration.’

The CAFC thus upheld the Board’s finding that motivation to combine was supported by substantial evidence.

II. Nexus

The Court began:

For objective evidence of secondary considerations to be relevant, there must be a nexus between the merits of the claimed invention and the objective evidence. See In re GPAC, 57 F.3d 1573, 1580 (Fed. Cir. 1995). A showing of nexus can be made in two ways: (1) via a presumption of nexus, or (2) via a showing that the evidence is a direct result of the unique characteristics of the claimed invention.

A patent owner is entitled to a presumption of nexus when it shows that the asserted objective evidence is tied to a specific product that “embodies the claimed features, and is coextensive with them.” Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. v. Philip Morris, Inc., 229 F.3d 1120, 1130 (Fed. Cir. 2000).When a nexus is presumed, “the burden shifts to the party asserting obviousness to present evidence to rebut the presumed nexus.” Id.; see also Yita LLC v. MacNeil IP LLC, 69 F.4th 1356, 1365 (Fed. Cir. 2023). The inclusion of noncritical features does not defeat a finding of a presumption of nexus. See, e.g., PPC Broadband, Inc. v. Corning Optical Commc’ns RF, LLC, 815 F.3d 734, 747 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (stating that a nexus may exist “even when the product has additional, unclaimed features”)

Initially, for a presumption of nexus, there is a requirement that the product embodies the invention and is coextensive with it. Brown & Williamson, 229 F.3d at 1130. The CAFC noted that neither party disputed that both the Forward Drive and the Bravo Four S embodied the claimed invention. See, e.g., J.A. 1211, 117:10–25, but emphasized that coextensiveness is a separate requirement. Fox Factory, 944 F.3d at 1374.

Volvo Penta, as Brunswick and the Board note, did not provide sufficient argument on coextensiveness. Rather, it submitted a mere sentence that the Forward Drive is a “commercial embodiment” of the ‘692 Patent and “coextensive with the claims”. The Board found this argument “conclusory” and the CAFC agreed. As above, “[t]he patentee bears the burden of showing that a nexus exists.” Fox Factory, 944 F.3d at 1373 (quoting WMS Gaming Inc. v. Int’l Game Tech., 184 F.3d 1339, 1359 (Fed. Cir. 1999)).

However, the court found that the Boards finding of a lack of nexus, independent of a presumption, not supported by evidence. Specifically, the Board found that Brunswick’s development of the Bravo Four S was “akin to ‘copying,’” and that its “own internal documents indicate that the Forward Drive product guided [Brunswick] to design the Bravo Four S in the first place.” Indeed, the undisputed evidence, as the Board found, shows that boat manufacturers strongly desired Volvo Penta’s Forward Drive and were urging Brunswick to bring a forward drive to market.

The court found that there is therefore a nexus between the unique features of the claimed invention, a tractor-type stern drive, and the evidence of secondary considerations.

III. Objective Indicia

The court began:

Objective evidence of nonobviousness includes: (1) commercial success, (2) copying, (3) industry praise, (4) skepticism, (5) long-felt but unsolved need, and (6) failure of others. See, e.g., Transocean Offshore Deepwater Drilling, Inc. v. Maersk Drilling U.S., Inc., 699 F.3d 1340, 1349–56 (Fed. Cir. 2012). The weight to be given to evidence of secondary considerations involves factual determinations, which we review only for substantial evidence. In re Couvaras, 70 F.4th 1374, 1380 (Fed. Cir. 2023).

The court found that “the Board’s analysis of [this] objective indicia of non-obviousness, including its assignments of weight to different considerations, was overly vague and ambiguous.”

For example, despite recognizing the importance of Brunswick internal documents demonstrating deliberate copying of the Forward Drive, and “finding copying, the Board only afforded this factor ‘some weight.’” The Federal Circuit held that this “assignment of only ‘some weight’” was insufficient in view of its precedent, which generally explains that “copying [is] strong evidence of non-obviousness,” and the “failure by others to solve the problem and copying may often be the most probative and cogent evidence of non-obviousness.” Panduit Corp. v. Dennison Mfg. Co., 774 F.2d 1082, 1099 (Fed. Cir. 1985), cert. granted, judgment vacated on other grounds, 475 U.S. 809 (1986) (“That Dennison, a large corporation with many engineers on its staff, did not copy any prior art device, but found it necessary to copy the cable tie of the claims in suit, is equally strong evidence of nonobviousness.”).

Regarding commercial success, the Board recognized that the record supported, and Brunswick did not contest, that boat manufacturers “strongly desired Volvo Penta’s Forward Drive and were urging Brunswick to bring a forward drive to market.” Nevertheless, the Board only afforded this factor “some weight.” The court stated that this finding was not supported by substantial evidence.

Regarding industry praise, the Board found that although the exhibits submitted “provide praise for the Forward Drive more generally, including mentioning its forward facing propellers, as claimed in the ’692 patent,” it also found that “many of the statements of alleged praise specifically discuss unclaimed features, such as adjustable trim and exhaust-related features.”

The court noted that the Board assigned industry praise, commercial success, and copying all “some weight” without explaining why it gave these three factors the same weight. The court concluded this was ambiguous, and so the Board had “failed to sufficiently explain and support its conclusions. See, e.g., Pers. Web Techs., LLC v. Apple, Inc., 848 F.3d 987, 993 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (remanding in view of the Board’s failure to “sufficiently explain and support [its] conclusions”); In re Nuvasive, Inc., 842 F.3d 1376, 1385 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (same).”

Next, the Court also determined that the Board failed to properly evaluate long-felt but unresolved need. In evaluating the evidence presented by Volvo Penta, the Board dismissed it as merely describing the benefits of the product without indicating a long-felt problem that others had failed to solve. Volvo Penta had cited articles in support of its position, but the Board, without explanation, gave the arguments very little weight. Upon review, the CAFC stated that the articles identified more than mere benefits and “indisputably identifies a long-felt need: safe wakesurfing on stern-drive boats.”

The CAFC touches upon the relevance of the time since the issuance of cited references. The CAFC agreed with the Board that “the mere passage of time from dates of the prior art to the challenged patents” does not indicate nonobviousness “their age can be relevant to long-felt unresolved need.” See Leo Pharm. Prods., 726 F.3d 1346, 1359 (Fed. Cir. 2013) (“The length of the intervening time between the publication dates of the prior art and the claimed invention can also qualify as an objective indicator of nonobviousness.”); cf. Nike, Inc. v. Adidas AG, 812 F.3d 1326, 1338 (Fed. Cir. 2016), overruled on other grounds by Aqua Prods., Inc. v. Matal, 872 F.3d 1290 (Fed. Cir. 2017). The CAFC stated that other factors such as “lack of market demand” can explain why a product was not developed for years, even decades after the prior art. However, when, as here, “evidence demonstrates that there was a market demand for at least” a period of that time (here, the market demand only existed for ten of the fifty years from the prior art reference), the fact that Brunswick itself owned one of the asserted should not be overlooked. That, it is certainly relevant that the asserted patents were long in existence and not obscure, but rather owned by the parties in this case.

Finally, the CAFC held that the Board’s ultimate conclusion that “Brunswick’s “strong evidence of obviousness outweighs Patent Owner’s objective evidence of nonobviousness” lacked a proper explanation for said conclusion.

Thus, ultimately the Court found that the Board failed to properly consider the evidence of objective indicia of nonobviousness and so vacated and remanded for further consideration consistent with the opinion.

Comments:

Motivation to combine a reference does not require a recognition of the primary or only metric by which an invention is measured, so long as it is at least a consideration.

Regarding a presumption of nexus, be reminded that (i) coextensiveness is a separate element and should be addressed as such; and that (ii) “[t]he patentee bears the burden of showing that a nexus exists” and this requires more than conclusory statements. Similarly, the PTO must support a finding of a lack of nexus with evidence not mere conclusory statements.

It also serves as a reminder to be thoughtful and thorough in presenting objective indicia of nonobviousness, not only during IPRs and other forms of litigation, but in prosecution too. Avoid citing arguments in conclusory fashion.

Tags: Motivation > nexus > objective indicia of nonobviousness > obviousness > secondary considerations

Do not omit an “essential element” of the original invention in the reissue claims

| August 29, 2023

In Re: FloatʻN’Grill LLC

Decided: July 12, 2023

Before Linn (author), Prost, and Cunningham

Summary:

When FloatʻN’Grill LLC filed a reissue application, they deleted an essential part of the original disclosure from reissue claims. The PTAB rejected those claims for failure to satisfy the original patent requirement of § 251. The CAFC affirmed the PTAB’s decision.

Details:

FloatʻN’Grill LLC (“FNG”) appeals from the decision of the PTAB affirming the Examiner’s rejection under 35 U.S.C. §§112(b) and 251 of claims 4, 8, 10-14, and 17-22 of FNG’s application for reissue of its U.S. Patent No. 9,771,132 (“’132 patent”).

The ’132 patent

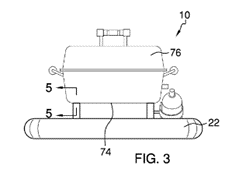

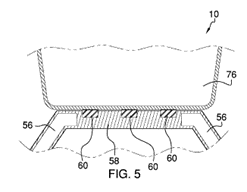

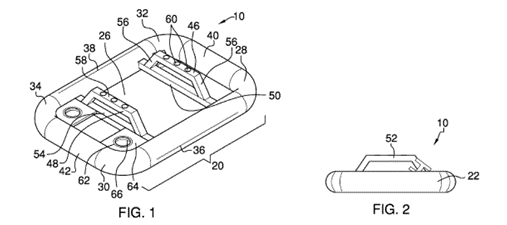

The ’132 patent is directed to a float designed to support a grill (76) so that a user can grill food in a body of water.

A floating apparatus (10) includes a float (20), a pair of grill supports (46 and 48), and an upper support (52). Each of the grill supports includes a plurality of magnets (60) disposed within a middle segment (58) of the upper support (52) of each grill support (46 and 48).

In particular, the specification states: “A flattened bottom side 74 of a portable outdoor grill 76 is removably securable to the plurality of magnets 60 and removably disposed immediately atop the upper support 52 of each” of the grill supports.” The specification does not disclose, suggest, or imply any other structures besides the plurality of magnets for removably securing the grill to the supports.

Independent claim 1 is a representative claim:

1. A floating apparatus for supporting a grill comprising. . .

. . .

a plurality of magnets disposed within the middle segment of the upper support of each of the right grill support and the left grill support . . .

. . .

wherein a flattened bottom side of a portable outdoor grill is removably securable to the plurality of magnets and removably disposed immediately atop the upper support of each of the right grill support and the left grill support.

Reissue Application

After the ’132 patent was issued, FNG filed a reissue application. However, none of the claims in the reissue application recites “the plurality of magnets” limitations. Rather, the claims recite the feature regarding the removable securing of a grill to the floating apparatus.

Independent claim 4 is a representative claim in the reissue application:

4. A floating grill support apparatus adapted to support a grill on water, the apparatus comprising:

a float having an outer rim wherein the float is buoyant and adapted to float in water and support a grill above the water; and

at least one base rod disposed within the outer rim wherein the base rod comprises a grill support member;

wherein the grill support member has an upper support portion;

wherein a bottom side of the grill is removably securable and removably disposed immediately atop the upper support portion of the grill support member.

The Examiner rejected the claims for failure to satisfy the reissue standard of 35 U.S.C. §251.

The Examiner indicated that the ’132 patent disclosed “a single embodiment of a floating apparatus for supporting a grill” using a “plurality of magnets” and did not disclose the plurality of magnets as being “an optional feature of the invention.” In addition, the Examiner indicated that the magnets are a critical element of the invention because the magnets alone are responsible for a safe and stable attachment between the floating apparatus and the grill.

The Examiner noted that since some claims in the reissue application do not require any magnets, require only a single magnet, and do not positively recite any magnets, they do not satisfy the original patent requirement of §251.

The PTAB

The PTAB maintained all the Examiner’s rejection.

The CAFC

The CAFC reviewed de novo.

The CAFC emphasized that for a reissue application, there is an additional statutory limitation in 35 U.S.C. §251 for a patentee seeking to change the scope of the claims through reissue – the “original patent” requirement of §251 (the reissue claims must be directed to “the invention disclosed in the original patent”).

The CAFC noted that the focus of the §251 analysis is on the invention disclosed in the original patent and whether that disclosure, on its face, explicitly and unequivocally described the invention as recited in the reissue claims.

The CAFC agreed with the PTAB that the reissue claims in this case are not directed to the invention disclosed in the original patent and, therefore, do not meet the original patent requirement of § 251.

The CAFC noted that the original specification describes a single embodiment of the invention characterized as a floating apparatus having a grill support including a plurality of magnets for safely and removably securing the grill to the float.

The CAFC held that the plurality of magnets component of the grill support structure are removed from the reissue claims, and that the original patent disclosure does not disclose these structures as optional. Also, the CAFC noted that the original patent disclosure does not provide any examples of alternative components or arrangements that might perform the functions of the plurality of magnets.

Therefore, the CAFC found that the plurality of magnets are essential parts of the invention because they are only disclosed structures for performing the task of removably and safely securing the grill to the float apparatus.

Accordingly, the CAFC held that the PTAB did not err in affirming the rejection of reissue claims for failure to satisfy the original patent requirement of § 251.

Takeaway:

- If Applicant would like to broaden the scope of the original invention, file a continuation or divisional application during the pendency of a parent application.

- Make sure that do not omit an “essential element” of the original invention in the reissue claims.

- Add more boilerplate statements and additional embodiments in the original application so that the broader reissue claims could be saved.

Tags: 35 U.S.C. § 251 > continuation application > divisional application > original patent requirement > Reissue application

Federal Circuit Affirms Alice Nix of Poll-Based Networking System

| August 10, 2023

Trinity Info Media v Covalent, Inc.

Decided: July 14, 2023

Before Stoll, Bryson and Cunningham.

Summary:

The Federal Circuit affirmed patent ineligibility of the Trinity’s poll-based networking system under Alice. The claims are directed to the abstract idea of matching based on questioning, something that a human can do. The additional features of a data processing system, computer system, web server, processor(s), memory, hand-held device, mobile phone, etc. are all generic components providing a technical environment for performing the abstract idea and do not detract from the focus of the claims being on the abstract idea. The specification also does not support a finding that the claims are directed to a technological improvement in computers, mobile phones, computer systems, etc.

Procedural History:

Trinity sued Covalent for infringing US Patent Nos. 9,087,321 and 10,936,685 in 2021. The district court granted Covalent’s 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss, concluding that the asserted claims are not patent eligible subject matter under 35 USC §101. Trinity appealed.

Decision:

Representative claim 1 from the ‘321 patent is as follows:

A poll-based networking system, comprising:

a data processing system having one or more processors and a memory, the memory being specifically encoded with instructions such that when executed, the instructions cause the one or more processors to perform operations of:

receiving user information from a user to generate a unique user profile for the user;

providing the user a first polling question, the first polling question having a finite set of answers and a unique identification;

receiving and storing a selected answer for the first polling question;

comparing the selected answer against the selected answers of other users, based on the unique identification, to generate a likelihood of match between the user and each of the other users; and

displaying to the user the user profiles of other users that have a likelihood of match within a predetermined threshold.

Representative claim 2 from the ‘685 patent is as follows:

A computer-implemented method for creating a poll-based network, the method comprising an act of causing one or more processors having an associated memory specifically encoded with computer executable instruction means to execute the instruction means to cause the one or more processors to collectively perform operations of:

receiving user information from a user to generate a unique user profile for the user;

providing the user one or more polling questions, the one or more polling ques-tions having a finite set of answers and a unique identification;

receiving and storing a selected answer for the one or more polling questions;

comparing the selected answer against the selected answers of other users, based on the unique identification, to generate a likelihood of match between the user and each of the other users;

causing to be displayed to the user other users, that have a likelihood of match within a predetermined threshold;

wherein one or more of the operations are carried out on a hand-held device; and

wherein two or more results based on the likelihood of match are displayed in a list reviewable by swiping from one result to another.

Looking at the claims first, the claimed functions of (1) receiving user information; (2) providing a polling question; (3) receiving and storing an answer; (4) comparing that answer to generate a “likelihood of match” with other users; and (5) displaying certain user profiles based on that likelihood are all merely collecting information, analyzing it, and displaying certain results which fall in the “familiar class of claims ‘directed to’ a patent ineligible concept,” which a human mind could perform. The court agreed with the district court’s finding that these claims are directed to an abstract idea of matching based on questioning.

The ‘685 patent adds the further function of reviewing matches using swiping and a handheld device. These features did not alter the court’s decision. The dependent claims also added other functional variations, such as performing matching based on gender, varying the number of questions asked, displaying other users’ answers, etc. These are all trivial variations that are themselves abstract ideas. The further recitation of the hand-held device, processors, web servers, database, and a “match aggregator” did not change the “focus” of the asserted claims. Instead, such generic computer components were merely limitations to a particular environment, which did not make the claims any less abstract for the Alice/Mayo Step 1.

With regard to software-based inventions, the Alice/Mayo Step 1 inquiry “often turns on whether the claims focus on the specific asserted improvement in computer capabilities or, instead, on a process that qualifies as an abstract idea for which computers are invoked merely as a tool.” In addressing this, the court looks at the specification’s description of the “problem facing the inventor.” Here, the specification framed the inventor’s problem as how to improve existing polling systems, not how to improve computer technology. As such, the specification confirms that the invention is not directed to specific technological solutions, but rather, is directed to how to perform the abstract idea of matching based on progressive polling.

Under Alice/Mayo Step 2, the claimed use of general-purpose processors, match servers, unique identifications and/or a match aggregator is merely to implement the underlying abstract idea. The specification describes use of “conventional” processors, web servers, the Internet, etc. The court has “ruled many times” that “invocations of computers and networks that are not even arguably inventive are insufficient to pass the test of an inventive concept in the application of an abstract idea.” And, no inventive concept is found where claims merely recite “generic features” or “routine functions” to implement an underlying abstract idea.

Trinity’s Argument 1

Claim construction and fact discovery was necessary, but not done, before analyzing the asserted claims under §101.

Federal Circuit’s Response 1

“A patentee must do more than invoke a generic need for claim construction or discovery to avoid grant of a motion to dismiss under § 101. Instead, the patentee must propose a specific claim construction or identify specific facts that need development and explain why those circumstances must be resolved before the scope of the claims can be understood for § 101 purposes.”

Trinity’s Argument 2

Under Alice/Mayo Step One, the claims included an “advance over the prior art” because the prior art did not carry out matching on mobile phones, did not employ “multiple match servers” and did not employ “match aggregators.”

Federal Circuit’s Response 2

A claim to a “new” abstract idea is still an abstract idea.

Trinity’s Argument 3

Humans cannot mentally engage in the claimed process because humans could not perform “nanosecond comparisons” and aggregate “result values with huge numbers of polls and members” nor could humans select criteria using “servers, storage, identifiers, and/or thresholds.”

Federal Circuit’s Response 3

The asserted claims do not require “nanosecond comparisons” nor “huge numbers of polls and members.”

Trinity’s claims can be directed to an abstract idea even if the claims require generic computer components or require operations that a human cannot perform as quickly as a computer. Compare, for example, with Electric Power Group, where the court held the claims to be directed to an abstract idea even though a human could not detect events on an interconnected electric power grid in real time over a wide area and automatically analyze the events on that grid. Likewise, in ChargePoint (electric car charging network system), claims directed to enabling “communication over a network” were abstract ideas even though a human could not communicate over a computer network without the use of a computer.

Trinity’s Argument 4

Claims are eligible inventions directed to improvements to the functionality of a computer or to a network platform itself.

Federal Circuit’s Response 4

As described in the specification, mere generic computer components, e.g., a conventional computer system, server, web server, data processing system, processors, memory, mobile phones, mobile apps, are used. Such generic computer components merely provide a generic technical environment for performing an abstract idea. The specification does not describe the invention of swiping or improving on mobile phones. Indeed, the ‘685 patent describes the “advent of the internet and mobile phones” as allowing the establishment of a “plethora” or “mobile apps.” As such, “the specification does not support a finding that the claims are directed to a technological improvement in computer or mobile phone functionality.”

Trinity’s Argument 5

The district court failed to properly consider the comparison of selected answers against other uses “based on the unique identification” which was a “non-traditional design” that allowed for “rapid comparison and aggregation of result values even with large numbers of polls and members.”

Federal Circuit’s Response 5

Use of a “unique identifier” does not render an abstract idea any less abstract.

On the other hand, the “non-traditional design” appears to be based on use of an “in-memory, two-dimensional array” that “provides for linear speed across multiple match servers” and permits “an immediate comparison to determine if the user had the same answer to that of another user.” However, the asserted claims do not require any such in-memory, two-dimensional array.

Trinity’s Argument 6

The district court failed to properly consider the generation of a likelihood of a match “within a predetermined threshold.” Without this consideration, “there would be no limit or logic associated with the volume or type of results a user would receive.”

Federal Circuit’s Response 6

This merely addresses the kind of data analysis that the abstract idea of matching would include, namely how many answers should be the same before declaring a match. This does not change the focus of the claimed invention from the abstract idea of matching based on questioning.

Trinity’s Argument 7

There is an inventive concept under Alice/Mayo Step 2 because the claims recite steps performed in a “non-traditional system” that can “rapidly connect multiple users using progressive polling that compare[s] answers in real time based on their unique identification (ID) (and in the case of the ’685 patent employ swiping)” which “represents a significant advance over the art.”

Federal Circuit’s Response 7

These conclusory assertions are insufficient to demonstrate an inventive concept. “We disregard conclusory statements when evaluating a complaint under Rule 12(b)(6).”

Takeaways:

The evisceration of software-related inventions as abstract ideas continues. Although the court looks at the “claimed advance over the prior art” in assessing the “directed to” inquiry under Alice Step 1, conclusory assertions of advances over the prior art are insufficient to demonstrate inventive concept under Alice Step 2, at least for a 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss. It remains to be seen what type of description of an “advance over the prior art” would not be “conclusory” and satisfy the “significantly more” inquiry to be an inventive concept under Alice Step 2.

The one glimmer of hope for the patentee might have been the use of an “in-memory, two-dimensional array” that “provides for linear speed across multiple match servers.” An example of patent eligibility based on use of such logical structures can be found in Enfish. However, if the specification does not describe this use of an in-memory two-dimensional array and the “technological” improvement resulting therefrom to be the “focus” of the invention, even this feature might not be enough to survive § 101.

Claim Construction Should be Well-Grounded in Intrinsic Evidence

| August 3, 2023

MEDYTOX, INC. v. GALDERMA S.A.

Decided: June 27, 2023

Before DYK, REYNA, and STARK, Circuit Judges.

Summary

The CAFC upheld a decision by the PTAB in a post-grant review involving a patent for a botulinum toxin treatment. The patent owner attempted to replace original claims with substitute claims was rejected by the Board, leading to the cancellation of the original claims and the finding that the substitute claims were unpatentable. The court affirmed the Board’s decision, emphasizing the challenges of amending claims in post-grant proceedings.

Background

Medytox owns U.S. Patent No. 10,143,728 (‘728 patent), issued in December 2018, which is directed to a method that uses an animal-protein-free botulinum toxin composition for cosmetic and non-cosmetic applications. Galderma filed a petition for post-grant review (PGR) proceedings at the PTAB to challenge the validity of ‘728 patent claims.

During the PGR proceedings, Medytox attempted to modify all 10 claims of its ‘728 patent and obtained initial feedback on proposed substitute claims under the PTAB’s amendment motion pilot program. The PTAB’s preliminary guidance revealed that Medytox did not meet the statutory requirements for submitting an amendment motion. However, the board acknowledged that the new phrase claiming “a responder rate at 16 weeks after the first treatment of 50% or greater” neither introduced new matter nor suggested a range of responder rates. Despite this, Galderma opposed Medytox’s substitute claims, arguing that the ‘728 patent’s specification only revealed responder rates up to 62% in clinical trials, whereas Medytox’s claim language encompassed a range of responder rates from 50% to 100%.

Contrary to its initial guidance, the PTAB issued a final written decision in the PGR proceedings, ruling that the substitute claims introduced new matter regarding to the responder rate limitation. Medytox asserted that the 50% responder rate was claimed as a minimum threshold and not a range. Nevertheless, the PTAB found the substitute claim language to be invalid for indefiniteness after reviewing the complete record, as “a skilled artisan would not have been able to achieve higher responder rates under the guidance provided in the specification without undue experimentation.” Ultimately, the Board cancelled the original claims 1-5 and 7-10 and also found that the substitute claims to be unpatentable.

Below, substitute claim 19 is provided as a representative of the substitute claims.

19. A method for treating glabellar lines

a conditionin a patient in need thereof, comprising:locally administering a first treatment of

therapeutically effective amount ofa botulinum toxin composition comprising a serotype A botulinum toxin in an amount pre-sent in about 20 units of MT10109L, a first stabilizer comprising a polysorbate, and at least one additional stabilizer, and that does not comprise an animal-derived product or recombinant human albumin;locally administering a second treatment of the botulinum toxin composition at a time interval after the first treatment;

wherein said time interval is the length of effect of the serotype A botulinum toxin composition as determined by physician’s live assessment at maximum frown;

wherein said botulinum toxin composition has a greater length of effect compared to about 20 units of BOTOX®, when

whereby the botulinum toxin composition exhibits a longer lasting effect in the patient when com-pared to treatment of the same condition with a botulinum toxin composition that contains an animal-derived product or recombinant human albumin dosed at a comparable amount andadministered in the same manner for the treatment of glabellar linesand to the same locations(s)as that of the botulinum toxin composition; andwherein said greater length of effect is determined by physician’s live assessment at maximum frown and requires a responder rate at 16 weeks after the first treatment of 50% or greater.

that does not comprise an animal-derived product or recombinant human albumin, wherein the condition is selected from the group consisting of glabellar lines, marionette lines, brow furrows, lateral canthal lines, and any combination thereof.

Discussion

The key issues in the case were the responder rate limitation and whether the substitute claims contained new matter not found in the patent specification. The responder rate limitation referred to the proportion of patients who responded favorably to the treatment with Medytox’s animal-protein-free botulinum toxin composition. In the appeal, Medytox contested the Board’s findings on claim construction, new matter, written description, and enablement, as well as the Board’s Pilot Program on amending practice and procedure under the Administrative Procedure Act.

The Board’s interpretation of the responder rate limitation as a range was the first issue addressed. Medytox argued that the responder rate limitation should be viewed as a binary (“yes-or-no”) inquiry, serving as a “threshold” for determining whether the animal protein-free composition has a more extended effect than BOTOX®.

According to Galderma, Medytox failed to cite intrinsic evidence supporting its suggested claim construction. Galderma also asserts that Medytox did not propose its “minimum threshold” interpretation of the responder rate limitation until after the Preliminary Guidance was released. Medytox did not substantively counter Galderma’s claim but instead insisted that extrinsic evidence supports their claim construction.

The court upheld the Board’s decision and noted that it is typically considered that intrinsic evidence, such as the specification and the prosecution history, is the most crucial consideration in a claim construction analysis. The court cited the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent landmark decision in Amgen v. Sanofi (2023) when nixing Medytox’s challenge to the PTAB’s lack of enablement determination. Under Amgen, “[t]he more one claims, the more one must enable,” and the court noted that data tables included with the ‘728 patent’s specification only disclosed responder rates of 52%, 61% and 62%. While the parties do not substantially dispute the responder rate limitation as a “threshold” or “range,” the Board’s construction of the responder rate limitation as a range in the substitute claims was ultimately affirmed.

Furthermore, the court concluded that the Board’s change in claim construction between its Preliminary Guidance and final written decision was not arbitrary and capricious and did not violate due process or the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). The court emphasized that the Board’s Preliminary Guidance, as indicated in its statement, is “initial, preliminary, [and] non-binding”, and only provides initial views on whether the patent owner has demonstrated a reasonable likelihood of meeting the requirements for filing an amendment motion. The court cited previous rulings which state that the Board must reevaluate matters based on the full record, especially when the standard changes, and that it is encouraged to modify its viewpoint if further development of the record necessitates such a change. Therefore, the Board’s decision to alter its claim construction for the responder rate limitation was not deemed arbitrary and capricious.

Takeaway

- The evolution of the record over the course of a proceeding can significantly impact the outcome, necessitating adjustments in views and decisions as the evidence develops.

- Arguments related to claim construction should be well-grounded in the intrinsic evidence, which includes the specification and the prosecution history, as these are typically the most important considerations in claim construction.

- Claims should be well-grounded in the specification.

UNEXPECTED RESULTS VERSUS UNEXPECTED MECHANISM

| July 28, 2023

In Re: John L Couvaras

Decided June 14, 2023

Before Lourie, Dyk and Stoll.

Summary

This precedential decision serves as a good lesson on what is necessary to overcome an obviousness rejection based on unexpected results. The applicant in this decision, however, failed to overcome the rejection due to arguing an unexpected mechanism instead of unexpected results.

Background

The applicant appeals a decision from the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) affirming the Examiner’s rejection of the pending claims as obvious over prior art. Representative claim 11 recites:

11. A method of increasing prostacyclin release in systemic blood vessels of a human individual with essential hypertension to improve vasodilation, the method comprising the steps of:

providing a human individual expressing GABA-a receptors in systemic blood vessels due to essential hypertension;

providing a composition of a dosage of a GABA-a agonist and a dosage of an ARB combined into a deliverable form, the ARB being an Angiotensin II, type 1 receptor antagonist;

delivering the composition to the human individual’s circulatory system by co-administering the dosage of a GABA-a agonist and the dosage of the ARB to the human individual orally or via IV;

synergistically promoting increased release of prostacyclin by blockading angiotensin II in the human individual through the action of the dosage of the ARB to reduce GABA-a receptor inhibition due to angiotensin II presence during a period of time, and

activating the uninhibited GABA-a receptors through the action of the GABA-a agonist during the period of time; and

relaxing smooth muscle of the systemic blood vessels as a result of increased prostacyclin release. (emphasis added).

The applicant had conceded during prosecution that GABA-a agonists and ARBs had been known as essential hypertension treatments for many decades. The Examiner agreed and found that the claimed results (increased release of prostacyclin; activating the uninhibited GABA-a receptors; relaxing smooth muscle of the systemic blood vessels) were not patentable because they naturally flowed from the claimed administration of the known antihypertensive agents.

On appeal to the PTAB, the applicant asserted that the prostacyclin increase was unexpected and that objective indicia had overcome any existing prima facie case of obviousness. The PTAB affirmed the rejection, holding that the claimed result of an increased prostacyclin release was inherent, and that the objective indicia arguments did not overcome the rejection because no evidence existed to support a finding of objective indicium.

Discussion

The PTAB’s legal determination is reviewed de novo, and the factual findings are reviewed for substantial evidence.

Couvaras asserts that (1) the Board erred in affirming that motivation to combine the art applied by the Examiner, (2) that the claimed mechanism of action was unexpected in that the Board erred in discounting its patentable weight by deeming it inherent, and (3) that the Board erred in weighing objective indicia of nonobviousness.

1. Motivation to Combine

As explained by the Examiner and affirmed by the Board, “[i]t is prima facie obvious to combine two compositions each of which is taught by the prior art to be useful for the same purpose, in order to form a third composition which is to be used for the very same purpose.” Couvaras asserted that the Board’s reasoning was too generic. However, it is undisputed that the antihypertensive agents recited in the claims existed and were known to treat hypertension.

Couvaras also asserted that even if there had been a motivation to combine, such motivation would fail to identify a finite number of identified, predicted solutions. The CAFC dismissed this argument because (1) it was made in a footnote and thus waived, (2) there was no evidence presented regarding a “substantial number of hypertension treatment agent classes”, and (3) the Board’s conclusion was supported by substantial evidence.

Regarding a reasonable expectation of success, Couvaras did not present any arguments against the Examiner’s findings when the rejection was appealed.

2. Unexpected Mechanism of Action

Couvaras contends that because the increased prostacyclin release was unexpected, it cannot be dismissed as having no patentable weight due to inherency, citing Honeywell International Inc. v. Mexichem Amanco Holdings S.A.,865 F.3d 1348, 1355 (FED. Cir. 2017). This decision, however, held that unexpected properties may cause what may appear to be an obvious composition to be nonobvious, not that the unexpected mechanisms of action must be found to make the known use of known compounds nonobvious. As stated in the opinion:

We have previously held that “[n]ewly discovered results of known processes directed to the same purpose are not patentable because such results are inherent.” In re Montgomery, 677 F.3d 1375, 1381 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (citation omitted); see also In re Huai-Hung Kao, 639 F.3d 1057, 1070–71 (Fed. Cir. 2011) (holding that a “food effect” was obvious because the effect was an inherent property of the composition). While mechanisms of action may not always meet the most rigid standards for inherency, they are still simply results that naturally flow from the administration of a given compound or mixture of compounds. Reciting the mechanism for known compounds to yield a known result cannot overcome a prima facie case of obviousness, even if the nature of that mechanism is unexpected.”

3. Weighing objective indicia of nonobviousness

To establish unexpected results, Couvaras needed to show that the co-administration of a GABA-a agonist and an ARB provided an unexpected benefit, such as, e.g., better control of hypertension, less toxicity to patients, or the ability to use surprisingly low dosages. The CAFC agreed with the Board that no such benefits have been shown, and therefore no evidence of unexpected results exists.

Takeaways

- Evidence needs to be presented to rebut a prima facie rejection. It seems that the applicant was attempting to assert that the combined use of the 2 agents provided unexpected results (better than what would be expected) based on synergy. As set forth in MPEP 716.02, greater than expected results are evidence of nonobviousness.

MPEP 716.02(a)

Evidence of a greater than expected result may also be shown by demonstrating an effect which is greater than the sum of each of the effects taken separately (i.e., demonstrating “synergism”). Merck & Co. Inc. v. Biocraft Laboratories Inc., 874 F.2d 804, 10 USPQ2d 1843 (Fed. Cir.), cert. denied, 493 U.S. 975 (1989). However, a greater than additive effect is not necessarily sufficient to overcome a prima facie case of obviousness because such an effect can either be expected or unexpected. Applicants must further show that the results were greater than those which would have been expected from the prior art to an unobvious extent, and that the results are of a significant, practical advantage. Ex parte The NutraSweet Co., 19 USPQ2d 1586 (Bd. Pat. App. & Inter. 1991) (Evidence showing greater than additive sweetness resulting from the claimed mixture of saccharin and L-aspartyl-L-phenylalanine was not sufficient to outweigh the evidence of obviousness because the teachings of the prior art lead to a general expectation of greater than additive sweetening effects when using mixtures of synthetic sweeteners.).

It seems that no evidence was presented to support the applicant’s argument of synergy. In reviewing the prosecution history, there were two interviews with the primary Examiner, one of which also included the Supervisory Examiner (SPE)[1]. In the interview summary, the Examiners indicated that the claims were too broad in that there were no amounts recited, no dose regime and/or no specific agents recited. It seems that a successful outcome could have been possible if evidence had been presented which was commensurate in scope with the claims.

- Once an Examiner establishes a prima facie rejection, the burden shifts to the applicant to prove otherwise.

[1] It is never a good idea to call on the SPE to attend an interview with a Primary Examiner. This not only angers a Primary Examiner but also the SPE.

THE MORE YOU CLAIM, THE MORE YOU MUST ENABLE

| July 12, 2023

Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi

Decided: May 18, 2023

Supreme Court of the United States. Opinion by Justice Gorsuch

Summary:

Amgen owns patents covering antibodies that help reduce levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. Amgen sued Sanofi for infringement of its patents in district court. Sanofi raised the defense of invalidity for lack of enablement because while Amgen provided amino acid sequences for 26 antibodies, the claims cover potentially millions more undisclosed antibodies. The district court granted a motion for JMOL for invalidity due to lack of enablement, the CAFC affirmed, and the Supreme Court affirmed.

Details:

Amgen’s patents are to PCSK9 inhibitors. PCSK9 is a naturally occurring protein that binds to and degrades LDL receptors. PCSK9 causes problems due to degradation of LDL receptors because LDL receptors extract LDL cholesterol from the bloodstream. A method used to inhibit PCSK9 is to create antibodies that bind to a particular region of PCSK9 referred to as the “sweet spot” which is a sequence of 15 amino acids out of PCSK9’s 692 total amino acids. An antibody that binds to the sweet spot can prevent PCSK9 from binding to and degrading LDL receptors. Amgen developed a drug named REPATHA and Sanofi developed a drug named PRALUENT, both of which provide a distinct antibody with its own unique amino acid sequence. In 2011, Amgen and Sanofi received patents covering the antibody used in their respective drugs.

The patents at issue are U.S. Patent Nos. 8,829,165 and 8,859,741 issued in 2014 which relate back to Amgen’s 2011 patent. These patents are different from the 2011 patents in that they claim the entire genus of antibodies that (1) “bind to specific amino acid residues on PCSK9,” and (2) “block PCSK9 from binding to LDL receptors.” The relevant claims are provided:

Claims of the ‘165 patent:

1. An isolated monoclonal antibody, wherein, when bound to PCSK9, the monoclonal antibody binds to at least one of the following residues: S153, I154, P155, R194, D238, A239, I369, S372, D374, C375, T377, C378, F379, V380, or S381 of SEQ ID NO:3, and wherein the monoclonal antibody blocks binding of PCSK9 to LDLR.

19. The isolated monoclonal antibody of claim 1 wherein the isolated monoclonal antibody binds to at least two of the following residues S153, I154, P155, R194, D238, A239, I369, S372, D374, C375, T377, C378, F379, V380, or S381 of PCSK9 listed in SEQ ID NO:3.

29. A pharmaceutical composition comprising an isolated monoclonal antibody, wherein the isolated monoclonal antibody binds to at least two of the following residues S153, I154, P155, R194, D238, A239, I369, S372, D374, C375, T377, C378, F379, V380, or S381 of PCSK9 listed in SEQ ID NO: 3 and blocks the binding of PCSK9 to LDLR by at least 80%.

Claims of the ‘741 patent:

1. An isolated monoclonal antibody that binds to PCSK9, wherein the isolated monoclonal antibody binds an epitope on PCSK9 comprising at least one of residues 237 or 238 of SEQ ID NO: 3, and wherein the monoclonal antibody blocks binding of PCSK9 to LDLR.

2. The isolated monoclonal antibody of claim 1, wherein the isolated monoclonal antibody is a neutralizing antibody.

7. The isolated monoclonal antibody of claim 2, wherein the epitope is a functional epitope.

In its application, Amgen identified the amino acid sequences of 26 antibodies that perform these two functions. Amgen provided two methods to make other antibodies that perform the described binding and blocking functions. Amgen refers to the first method as the “roadmap,” which provides instructions to:

(1) generate a range of antibodies in the lab; (2) test those antibodies to determine whether any bind to PCSK9; (3) test those antibodies that bind to PCSK9 to determine whether any bind to the sweet spot as described in the claims; and (4) test those antibodies that bind to the sweet spot as described in the claims to determine whether any block PCSK9 from binding to LDL receptors.

Amgen refers to the second method as “conservative substitution” which provides instructions to:

(1) start with an antibody known to perform the described functions; (2) replace select amino acids in the antibody with other amino acids known to have similar properties; and (3) test the resulting antibody to see if it also performs the described functions.

Amgen sued Sanofi for infringement of claims 19 and 29 of the ‘165 patent and claim 7 of the ‘741 patent. Sanofi raised the defense of invalidity because Amgen had not enabled a person skilled in the art to make and use all of the antibodies that perform the two functions Amgen described in the claims. Sanofi argued that Amgen’s claims cover potentially millions more undisclosed antibodies that perform the same two functions than the 26 antibodies identified in the patent.

The court provided an explanation of the law and policy regarding the enablement requirement. 35 U.S.C. § 112 requires that a specification include “a written description of the invention, and of the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art … to make and use the same.” The court stated:

the law secures for the public its benefit of the patent bargain by ensuring that, upon the expiration of [the patent], the knowledge of the invention [i]nures to the people, who are thus enabled without restriction to practice it.

The court stated that “the specification must enable the full scope of the invention as defined by its claims.” Specifically, the court stated:

If a patent claims an entire class of processes, machines, manufactures, or compositions of matter, the patent’s specification must enable a person skilled in the art to make and use the entire class.

The court emphasized that the enablement requirement does not always require a description of how to make and use every single embodiment within a claimed class. A few examples may suffice if the specification also provides “some general quality … running through” the class. A specification may also not be inadequate just because it leaves a skilled artisan to engage in some measure of adaptation or testing, i.e., a specification may call for a reasonable amount of experimentation to make and use a patented invention. “What is reasonable in any case will depend on the nature of the invention and the underlying art.”

Regarding this case, the court stated that while the 26 exemplary antibodies provided by Amgen are enabled by the specification, the claims are much broader than the specific 26 antibodies. And even allowing for a reasonable degree of experimentation, Amgen has failed to enable the full scope of the claims.

The court stated that Amgen seeks to monopolize an entire class of things defined by their function and that this class includes a vast number of antibodies in addition to the 26 that Amgen has described by their amino acid sequences. “[T]he more a party claims, the broader the monopoly it demands, the more it must enable.”

Amgen argued that the claims are enabled because scientists can make and use every undisclosed but functional antibody if they simply follow Amgen’s “roadmap” or its proposal for “conservative substitution.” The court stated that these instructions amount to two research assignments and that they leave scientists “forced to engage in painstaking experimentation to see what works.” The court referred to Amgent’s two methods as “a hunting license.”

Comments

The key takeaway from this case is that the broader your claims are, the more your specification must enable. If it is difficult to show enablement for every embodiment claimed, then make sure your specification describes some general quality throughout the class or genus. A reasonable amount of experimentation is permissible for enablement, but reasonableness will depend on the nature of the invention and the underlying art.

Joint Inventorship Gone Up In Smoke For Want of Significant Contribution

| June 16, 2023

HIP, INC. v. HORMEL FOODS CORPORATION

Decided: May 2, 2023

Before Lourie, Clevenger, and Taranto. Opinion by Lourie.

Summary