Post-filing examples, even if made by different method than prior art, may be relied upon to show inherency, particularly if patent owner fails to show that inherent feature is absent in prior art

| January 21, 2020

Hospira, Inc. v. Fresenius Kabi USA, LLC

January 9, 2020

Lourie, Dyk, Moore. Opinion by Lourie.

Summary

The CAFC upheld the obviousness of claims based on an inherency theory. In particular, the CAFC saw no fault in the conclusion that the combination of prior art possessed an inherent property even though the data demonstrating the inherent property was from post-filing examples made by a different method than the combination of cited art. This is because the patent owner failed to demonstrate any situation where the inherent property was not present.

Details

Background

Hospira is the owner of U.S. Patent No. 8,648,106. Fresenius filed an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) stipulating to infringement of claim 6 of the ‘106 patent, but arguing that this claim is invalid. Claim 6 (which depends on claim 1) recites as follows:

6. [A ready to use liquid pharmaceutical composition for parenteral administration to a subject, comprising dexmedetomidine or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof disposed within a sealed glass container, wherein the liquid pharmaceutical composition when stored in the glass container for at least five months exhibits no more than about 2% decrease in the concentration of dexmedetomidine,]

[] wherein the dexmedetomidine or pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof is at a concentration of about 4 μg/mL.

Dexmedetomidine is a sedative that was originally patented in the 1980’s. In 1989, safety studies were performed using a 20 µg/mL dosage in humans, but were eventually abandoned due to adverse side effects.

In 1994, FDA approval was granted to market a 100 µg/mL dose of dexmedetomidine under the name “Precedex Concentrate.” Precedex Concentrate was provided in 2 mL sealed glass vials/ampoules with coated rubber stoppers. Precedex Concentrate was sold with instructions for diluting to a concentration of 4 µg/mL prior to use.

Additionally, in 2002, a 500 µg/mL “ready to use” formulation of dexmedetomidine was granted approval for veterinary use in Europe. This product was called Dexdomitor, and was stored in 10 mL glass vials sealed with a coated rubber stopper. Dexdomitor has a 2 year shelf life.

The ‘106 patent explained that the prior art dexmedetomidine was problematic due to the requirement for dilution, and disclosed a premixed, “ready to use” formulation, which can be administered without dilution. The ‘106 patent stated that the invention was based in part on the discovery that the premixed dexmedetomidine “remains stable and active after prolonged storage.” The specification included studies of dexmedetomidine potency over time under different storage conditions, such as the material of the container. Further, the specification disclosed a manufacturing method that provided nitrogen gas into the headspace of the bottle.

District Court

The district court concluded that claim 6 was obvious in view of (a) the combination of Precedex Concentrate (100 µg/mL requiring dilution) and the knowledge of a person skilled in the art, and (b) the combination of Precedex Concentrate (100 µg/mL requiring dilution) and Dexdomitor (500 µg/mL not requiring dilution). In particular, the district court focused on the “4 µg/mL preferred embodiment”: a glass container made of glass and a rubber-coated stopper with ready to use 4 µg/mL dexmedetomidine. The main issue related to the “about 2%” limitation.

The district

court concluded that the “about 2%” limitation was inherent in the prior art’s

“4 µg/mL preferred embodiment.” To reach this conclusion, the district court

relied on evidence of 20+ tested samples, all of which met the “about 2%”

limitation. The court also relied on

expert testimony that the concentration of dexmedetomidine does not impact its

stability. Further, the court relied on the fact that neither the label of

Precedex Concentrate nor the label of Dexdomitor mentions chemical

stabilizers. Importantly, the district

court found insufficient evidence that it would have been expected that a lower

concentration of dexmedetomidine would reduce stability, or that oxidation

would occur in the absence of a nitrogen gas environment. The district court concluded that dexmedetomidine

is a “rock stable molecule” and that claim 6 is therefore invalid as obvious in

view of the prior art.

CAFC

At the CAFC, the main issue raised was whether the inherency conclusion of the district court was improper because it relied on non-prior art embodiments, rather than the alleged obvious combination of prior art. In particular, the data relied upon by the district court was entirely from Hospira’s NDA for Precedex Premix and Fresenius’s ANDA product. Both of these are after the filing date of the application. Both were made using the nitrogen gas environment method as described in the specification. As such, Hospira argued that it cannot be said that the data demonstrate the inherency of a preferred embodiment which may or may not be made using this manufacturing process.

However, the CAFC agreed with Fresenius that it was not an error to point to post-filing data in support of an inherency conclusion. Although the later evidence is not prior art, it can nonetheless be used to demonstrate the properties of the prior art. The NDA and ANDA data merely served as evidence to show whether there was the decrease in concentration over time of the 4 µg/mL preferred embodiment.

Additionally, the CAFC noted that claim 6 is not a method claim or a product-by-process claim. Since claim 6 includes no limitations relating to a nitrogen gas environment in the glass container, such limitations should not be read into the claim. Thus, the district court properly ignored the process by which the samples were prepared when considering inherency.

The CAFC then highlighted that the record included evidence that concentration does not affect the stability of dexmedetomidine, and also criticized Hospira for failing to present any examples of the 4 µg/mL preferred embodiment which did not satisfy the “about 2%” limitation. Furthermore, Hospira failed to demonstrate that the reason why the 20+ examples satisfied the “about 2%” limitation was because of the nitrogen gas in the glass container, and likewise that samples made by a different method would fail to satisfy the “about 2%” limitation.

Additionally, Hospira argued that the district court applied the wrong standard to inherency by applying a “reasonable expectation of success” standard. Although the CAFC agreed that the district court conflated two issues, they found that the district court’s “unnecessary analysis” was a harmless error and does not impact the outcome of the case. In other words, if a property is inherently present, there is no further question of whether one has a reason expectation of success in obtaining this property.

Returning to the merits, the CAFC concluded that claim 6 is obvious. Since there are no other relevant limitations recited in claim 6, the mere recitation of the inherent “about 2% limitation” cannot render the claim nonobvious. Rather, the patent was merely based on a discovery that dexmedetomidine is stable after long-term storage, but does not require any additional manufacturing limitations or the like.

Takeaway

-Applicants and patent owners should be aware that post-filing data can demonstrate inherency of prior art in some situations.

-When facing an issue of inherency, the Applicant or patent owner should focus on providing evidence to demonstrate the lack of an allegedly inherent feature in some situations, rather than criticizing the experimental design of the data alleged to show inherency.

-Applicants and patent owners should take care that non-inherency arguments are commensurate in scope with the claims. Here, the patent owner should have presented evidence relating to differences between drug potency in a nitrogen gas environment (as in the data relied upon by the court) as compared to a normal air environment (as in the combination of prior art). Although the claims do not require any particular environment, such data could have shown that even if the nitrogen gas environment (not prior art) satisfied the “about 2% limitation,” the non-nitrogen gas environment (prior art) did not necessarily satisfy the “about 2% limitation.”

-Applicants should be sure to claim all disclosed important features. In this case, positively reciting the nitrogen gas environment and the container at a minimum level of detail may have been sufficient to save the claims from obviousness.

Disavowal – Construing an element in a patent claim to require what is not recited in the claim but is described in an embodiment of the specification

| January 14, 2020

Techtronic Industries Co. Ltd. v. International Trade Commission

December 12, 2019

Lourie, Dyk, and Wallach, Circuit Judges. Court opinion by Lourie.

Summary

The Federal Circuit reversed the Commission’s claim construction order reversing the ALJ’s construction of the term “wall console” in each of claims in the patent in suit, holding that the ALJ properly construed the term “wall console” as “wall-mounted control unit including a passive infrared detector” because each section of the specification evinces that the patent disavowed coverage of wall consoles lacking a passive infrared detector. Consequently, the Court reversed the Commission’s determination of infringement as well because the parties agreed that the appellants do not infringe the patent under the ALJ’s claim construction.

Details

I. background

1. The Patent in Suit – U.S. Patent 7,161,319 (the “‘319 patent”)

Intervenor Chamberlain Group Inc. (“Chamberlain”) owns the ‘319 patent, which discloses improved “movable barrier operators,” such as garage door openers. Claim 1, a representative claim, reads as follows:

1. An improved garage door opener comprising

a motor drive unit for opening and closing a garage door, said motor drive unit having a microcontroller

and a wall console, said wall console having a microcontroller,

said microcontroller of said motor drive unit being connected to the microcontroller of the wall console by means of a digital data bus.

2. Prior Proceedings

In July 2016, Chamberlain filed a complaint at the Commission, alleging that Techtronic Industries Co. Ltd. and others (collectively, “Appellants”) violated Section 337(a)(1)(B) of the Tariff Act of 1930 by the “importation into the United States, the sale for importation, and the sale within the United States after importation” of Ryobi Garage Door Opener models that infringe the ‘319 patent.

The only disputed term of the ‘319 patent was “wall console.” The ALJ concluded that Chamberlain had disavowed wall consoles lacking a passive infrared detector because the ‘319 patent sets forth its invention as a passive infrared detector superior to those of the prior art by virtue of its location in the wall console, rather than in the head unit, and that the only embodiment in the ‘319 patent places the passive infrared detector in the wall console as well.

The Commission reviewed the ALJ’s order and issued a decision reversing the ALJ’s construction of “wall console” and vacating his initial determination of non-infringement. The Commission presented following reasons for the reversal: (i) while “the [‘319] specification describes the ‘principal aspect of the present invention’ as providing an improved [passive infrared detector] for a garage door operator,” the specification discloses other aspects of the invention, and a patentee is not required to recite in each claim all features described as important in the written description; (ii) the claims of U.S. Patent 6,737,968, which issued from a parent application, expressly located the passive infrared detector in the wall console, “demonstrat[ing] the patentee’s intent to claim wall control units with and without [passive infrared detectors];” and (iii) the prosecution history of the ‘319 patent lacked “the clear prosecution history disclaimer.”

Under the Commission’s construction, the ALJ found that Appellants infringed the ‘319 patent. Accordingly, the Commission entered the Remedial Orders against the Appellants.

The appeal followed.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit unanimously sided with the Appellants, concluding that Chamberlain disavowed coverage of wall consoles without a passive infrared detector because “the specification, in each of its sections, discloses as the invention a garage door opener improved by moving the passive infrared detector from the head unit to the wall console.”

The court opinion authored by Judge Lourie started scrutiny of the ‘319 specification with the background section. The court opinion found that the background section discloses that the prior art taught the use of passive infrared detectors in the head unit of the garage door opener to control the garage’s lighting, but that locating the detector in the head unit was expensive, complicated, and unreliable (emphases added). The court opinion moved on to state, [t]he ‘319 patent therefore sets out to solve the need for “a passive infrared detector for controlling illumination from a garage door operator which could be quickly and easily retrofitted to existing garage door operators with a minimum of trouble and without voiding the warranty.”

The court opinion further stated, “[t]he remaining sections of the patent—even the abstract—disclose a straightforward solution: moving the detector to the wall console” (emphasis added).

The court opinion dismissed the Commission’s argument that “[n]owhere does the ‘319 patent state that it is impossible or even infeasible to locate a passive infrared detector at some other location” by pointing out, “the entire specification focuses on enabling placement of the passive infra-red detector in the wall console, which is both responsive to the prior art deficiency the ’319 patent identifies and repeatedly set forth as the objective of the invention.”

As for the “other aspects of the invention” partially relied on by the Commission, the court opinion stated, “[t]he suggestion that the patent recites another invention—related to programming the microcontroller—in no way undermines the conclusion that the infrared detector must be on the wall unit .” More specifically, in response to Chamberlain’s and the Commission’s argument that portions of the description, particularly col. 4 l. 60–col. 7 l. 26, concern an exemplary method of programming the microcontroller to interact with the head unit by means of certain digital signaling techniques, matters not strictly related to the detector, the court opinion stated, “the entire purpose of this part of the description is to enable placement of the detector in the wall console, and it never discusses programming the microcontroller or applying digital signaling techniques for any purpose other than transmitting lighting commands from the wall console.”

Finally, the court opinion rejected the contention of Chamberlain and the Commission that the ‘319 patent’s prosecution history is inconsistent with disavowal, by stating, “there is [n]o requirement that the prosecution history reiterate the specification’s disavowal.”

In view of the above, the Court concluded that the ‘319 patent disavows wall consoles lacking a passive infrared detector. Accordingly, the Court reversed the Commission’s claim construction order and the determination of infringement.

Takeaway

· Disavowal, whether explicit or implicit, may cause a claim term to be construed narrower than an ordinary meaning of the term.

· Disavowal may be found with reference to an entire portion of the specification including an abstract and background section.

The United States Patent and Trademark Office cannot recover salaries of its lawyers and paralegals in civil actions brought under 35 U.S.C. §145

| December 26, 2019

Peter v. Nantkwest, Inc.

December 11, 2019

Opinion by Justice Sotomayor (unanimous decision)

Summary

The “American Rule” is the principle that parties are responsible for their own attorney’s fees. While the Patent Act requires applicants who choose to pursue civil action under 35 U.S.C. §145 to pay the expenses of the proceedings, the Supreme Court found that the American Rule’s presumption applies to §145, and the “expenses” does not include salaries of its lawyers and paralegals.

Details

There are two possible ways in which a dissatisfied applicant may appeal the final decision of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board. One option is to appeal to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit under 35 U.S.C. §141. In choosing this avenue, the applicant will not be able to offer new evidence that was not presented before the USPTO. The other option is to seek remedy in filing a civil action against the Director of the USPTO in federal district court under 35 U.S.C. §145. Unlike under 35 U.S.C. §141, the applicant may introduce new evidence, and the district court would make de novo determinations based on the new evidence and the administrative record before the USPTO. Because 35 U.S.C. §145 allows for an applicant to introduce new evidence, the litigation can be lengthy and expensive. For this reason, the Patent Act requires applicants who choose to file a civil action under 35 U.S.C. §145 to pay “[a]l the expenses of the proceedings.” 35 U.S.C. §145.

In this case, the USPTO denied NantKwest, Inc’s patent application, which was directed to a method for treating cancer. NantKwest Inc. then filed a complaint against the Director of the USPTO in the Eastern District of Virginia under 35 U.S.C. §145. The District Court granted summary judgment to the USPTO, which the Federal Circuit affirmed. The USPTO moved for reimbursement of expenses, including the pro rata salaries of the USPTO attorneys and paralegals who worked on the case. The Supreme Court noted in its opinion that this was “the first time in the 170-year history of §145” that the reimbursement of such salaries were requested as a part of expenses. The District Court denied the USPTO’s motion. NantKwest, Inc. v. Lee, 162 F. Supp. 3d 540 (E.D. Va. 2016). Then a divided Federal Circuit panel reversed. NantKwest, Inc. v. Matal, 860 F. 3d 1352 (2017). The en banc Federal Circuit voted sua sponte to rehear the case, and reversed the panel over a dissent, holding that the “American Rule” (the principle that parties are responsible for their own attorney’s fees) applied to §145, after examining the plain text, statutory history, the judicial and congressional understanding of similar language, and policy considerations. NantKwest, Inc. v. Iancu, 898 F. 3d 1177 (2018). The Supreme Court granted certiorari.

The Supreme Court first notes as the “basic point of reference” the principle of the “American Rule” which is that “[e]ach litigant pays his own attorney’s fees, win or lose, unless a statute or contract provides otherwise.” While the USPTO did not dispute this principle, it argued that the presumption applies only to prevailing-party statutes, and as §145 requires one party to pay all expenses, regardless of outcome, it is therefore not subject to the presumption. However, the Supreme Court stated that Sebelius v. Cloer, 569 U.S. 369 (2013) confirm that the presumption against fee shifting applies to all statutes, including statute like §145 that do not explicitly award attorney’s fees to “prevailing parties.”

The Supreme Court then analyzed whether Congress intended to depart from the American Rule presumption. The Supreme Court first looked at the plain text, reading the term alongside neighboring words in the statute, and concluded that the plain text does not overcome the American Rule’s presumption against fee shifting. The Supreme Court also looked at statutory usage, and found that “expenses” and “attorney’s fees” appear in tandem across various statutes shifting litigation costs, indicating “that Congress understands the two terms to be distinct and not inclusive of each other.” While some other statutes refer to attorney’s fees as a subset of expenses, the Supreme Court stated that they show only that attorney’s fees can be included in “expenses” when defined as such.

Based on the foregoing, the Supreme Court concluded that the USPTO cannot recover salaries of its lawyers and paralegals in civil actions brought under 35 U.S.C. §145.

Takeaway

The USPTO has recovered attorney costs under a similar trademark law, 15 U.S.C. 1071, in the 2015 Fourth Circuit decision of Shammas v. Focarino, 114 USPQ2d 1489 (4th Cir. 2015). While the Supreme Court does not mention the applicability of the interpretation of “expenses” under 35 U.S.C. §145 to the interpretation of “expenses” in 15 U.S.C. 1071(b)(3), we would expect the Supreme Court to interpret “expenses” the same way in both of these statutes.

Heightened “original patent” written description standard applies for reissue patents

| December 20, 2019

Forum US Inc., v. Flow Valve, LLC.

June 17, 2019

Before Reyna, Schall, and Hughes. Opinion by Reyna.

Summary

The CAFC affirmed a district court decision holding that Flow Valve’s Reissue Patent No. RE 45,878 (“the Reissue patent”) is invalid because of insufficiently supported broadening claims. The original patent “must clearly and unequivocally disclose the newly claimed invention as a separate invention,” otherwise the claims in the reissue patent do not comply with the original patent requirement of 35 USC 251.

Details

Flow Valve’s original Patent No. 8,215,213 (“the original patent), entitled “Workpiece Supporting Assembly” relates to machined pipe fittings typically used in the oil and gas industry. The written description and drawings disclose only embodiments with arbors.

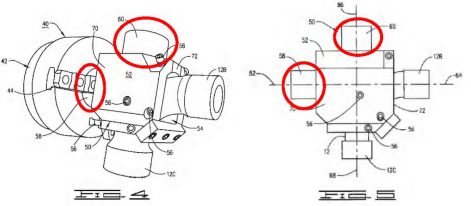

Figs. 4 and 5 from the original patent with arbors circled in red:

Claim 1 of the original patent also expressly claimed the arbors (emphasis added):

A workpiece machining implement comprising:

a body member having an internal workpiece channel, the body member having a plurality of body openings communicating with the internal workpiece channel;

means supported by the body member for positioning a workpiece in the internal work piece in the internal workpiece channel so that extending workpiece portions of the workpiece extend from selected ones of the body openings;

a plurality of arbors supported by the body member, each arbor having an axis coincident with a datum axis of one of the extending workpiece portions; and

means for rotating the workpiece supporting assembly about the axis of a selected one of the arbors.

When Flow Valve filed the reissue patent application, the patentees broadened the claims by adding seven new claims, where the arbor limitations were replaced by a “pivotable” limitation. Claim 14 is representative of the reissue patent:

Claim 14 of the reissue patent:

A workpiece supporting assembly for securing an elbow during a machining process that is performed on the elbow by operation of a workpiece machining implement, the workpiece supporting assembly comprising:

a body having an internal surface defining a channel, the internal surface sized to receive a medial portion of the elbow when the elbow is operably disposed in the channel; and

a support that is selectively positionable to secure the elbow in the workpiece supporting assembly, the body pivotable to a first pivoted position, the body sized so that a first end of the elbow extends from the channel and beyond the body so the first end of the elbow is presentable to the workpiece machining implement for performing the machining process, the body pivotable to a second position and sized so that a second end of the elbow extends from the channel beyond the body so the second end of the elbow is presentable to the workpiece machining implement for performing the machining process.

Forum US, Inc. sued Flow Valve for a declaratory judgment of invalidity of the reissue patent, arguing that the added reissue claims were invalid because they did not comply with the original patent requirement under 35 USC 251.

In particular, Forum argued that the claims broadened the original patent claims by omitting the arbor limitations, which is a violation of the original patent requirement of Reissue patent because the original patent did not disclose an invention without arbors.

In response, Flows Valve supplied an expert declaration asserting that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have understood from the specification that not every embodiment requires “a plurality of arbors” and that the arbors are an optional feature.

The district court granted Forum’s summary judgement, holding that “no matter what a person of ordinary skill would recognize, the specification of the original patent must clearly and unequivocally disclose the newly claimed invention in order to satisfy the original patent rule.”

Flows Valve appealed but the CAFC affirmed the district court’s decision.

In affirming the district court’s decision, the CAFC relied on two cases U.S. Indus. Chems., Inc. v. Carbide & Carbon Chems. Corp., 315 U.S. 668 (1942), and Antares Pharma, Inc. v. Medac Pharma Inc., 771 F.3d 1354 (Fed. Cir 2014), to the effect that, for broadening reissue claims, “it is not enough that an invention might have been claimed in the original patent because it was suggested or indicated in the specification”, instead, the original patent “must clearly and unequivocally disclose the newly claimed invention as a separate invention.”

Like the District Court, the Appeals Court discounted the expert declaration, commenting that “when a person of ordinary skill in the art would understand ‘does not aid the court in understanding what the’ patent actually say.”

Take away

- Heightened “original patent” written description standard applies for reissue patents.

- Expert testimony on the understanding of a person of skill in the art as evidence is insufficient.

- If it is likely in the foreseeable future to have the needs to broaden the claims, use a continuation application so that applicant does not have to meet the additional “clear and unequivocal disclosure as separate invention” requirement of a broadening reissue.

WHEN IS PRIOR ART ANALOGOUS?

| November 29, 2019

Airbus v. Firepass

November 8, 2019

Lourie, Moore, and Stoll

Summary:

To determine whether a reference is “analogous prior art,” one must first ask whether the reference is from the same “field of endeavor” as claimed invention. If not, one must ask whether the reference is “reasonably pertinent” to the particular problem addressed by the claimed invention.

As phrased by the CAFC here, a reference is “reasonably pertinent” if

an ordinarily skilled artisan would reasonably have consulted in seeking a solution to the problem that the inventor was attempting to solve, [so that] the reasonably pertinent inquiry is inextricably tied to the knowledge and perspective of a person of ordinary skill in the art at the time of the invention.

Thus, one should consider (i) in which areas one skilled in the art would reasonably look, and (ii) what that skilled person would reasonably search for, in trying to address the problem faced by the inventor. Accordingly, courts or examiners should consider evidence cited by the parties or the applicant that demonstrates “the knowledge and perspective of a person of ordinary skill in the art at the time of the invention.”

If a reference fails both the “field of endeavor” and the “reasonably pertinent” tests, it is not analogous prior art and not available for an obviousness rejection.

Background:

Challenger Airbus filed an inter partes reexamination against a patent owned by Firepass. The examiner rejected the claims at issue here as being obvious over the Kotliar reference in view of other prior art. The examiner also rejected other claims, not in issue here, as being obvious over Kotliar in view of four prior references (Gustafsson, the 1167 Report, Luria, and Carhart).

The claimed invention is an enclosed fire prevention and suppression system (for instance, computer rooms, military vehicles, or spacecraft), which extinguishes fire with an atmosphere of breathable air. The inventor found that a low-oxygen atmosphere (16.2% or slightly lower), maintained at normal pressure, would inhibit fire and yet be breathable by humans. Normal pressure is maintained by added nitrogen gas.

The patent contains the following independent claim that was added during the reexamination:

A system for providing breathable fire-preventive and fire suppressive atmosphere in enclosed human-occupied spaces, said system comprising:

an enclosing structure having an internal environment therein containing a gas mixture which is lower in oxygen content than air outside said structure, and an entry communicating with said internal environment;

an oxygen-extraction device having a filter, an inlet taking in an intake gas mixture and first and second outlets, said oxygen-extraction device being a nitrogen generator, said first outlet transmitting a first gas mixture having a higher oxygen content than the intake gas mixture and said second outlet transmitting a second gas mixture having a lower oxygen content than the intake gas mixture;

said second outlet communicating with said internal environment and transmitting said second mixture into said internal environment so that said second mixture mixes with the atmosphere in said internal environment;

said first outlet transmitting said first mixture to a location where it does not mix with said atmosphere in said internal environment;

said internal environment selectively communicating with the outside atmosphere and emitting excessive internal gas mixture into the outside atmosphere;

said intake gas mixture being ambient air taken in from the external atmosphere outside said internal environment with a reduced humidity; and

a computer control for regulating the oxygen con-tent in said internal environment.

The Board of Appeals reversed the examiner’s rejection, finding that Kotliar is not analogous prior art. The Board stated that the examiner had not articulated a “rational underpinning that sufficiently links the problem [addressed by the claimed invention] of fire suppression/prevention confronting the inventor” to the disclosure of Kotliar, “which is directed to human therapy, wellness, and physical training.” Significantly, the Board did not consider Airbus’ argument that “breathable fire suppressive environments [were] well-known in the art,” stating that the four references, relied on by Airbus, were not used by the examiner for the rejection of the claims in issue here.

Discussion:

The CAFC began its analysis by citing the “field of endeavor” and the “reasonably pertinent” tests mentioned above.

With respect to “field of endeavor,” the CAFC agreed with the Board. The Court explained that the disclosure of the references is the primary focus, but that courts and examiners must also consider each reference’s disclosure in view of the “the reality of the circumstances” and “weigh those circumstances from the vantage point of the common sense likely to be exerted by one of ordinary skill in the art in assessing the scope of the endeavor.”

Here, the Board found that the “field of endeavor” for the patent to be “devices and methods for fire prevention/suppression,” citing the preamble of the claim, the title and specification of the patent. Kotliar, on the other hand, concerns “human therapy, wellness, and physical training,” based on its title and specification. The Board concluded that Kotliar was outside the field of endeavor of the claimed invention, particularly in view of the fact that Kotliar never mentions “fire.”

The CAFC found that the Board’s conclusion is supported by substantial evidence.

Airbus argued that the Board should have considered the four references—Gustafsson, the 1167 Report, Luria, and Carhart—to which show that “a POSA would have known and appreciated that the breathable hypoxic air produced by Kotliar is fire-preventative and fire-suppressive, even though Kotliar does not state this” (emphasis in original). The CAFC disagreed, stating that Board’s failure to consider these references, if error, was harmless error. The CAFC explained that

a reference that is expressly directed to exercise equipment and fails to mention the word “fire” even a single time—falls within the field of fire prevention and suppression. Such a conclusion would not only defy the plain text of Kotliar, it would also defy “common sense” and the “reality of the circumstances” that a factfinder must consider in determining the field of endeavor.

The CAFC, however, came to the opposite conclusion with respect to the “reasonably pertinent” test. As with the “field of endeavor” test, the Board had failed to consider the four references. The CAFC found that this was a mistake.

In determining whether a reference is “reasonably pertinent” to the particular problem addressed by the claimed invention, for assessing whether a reference is analogous prior art, the court or the examiner should consider (i) in which areas one skilled in the art would reasonably look, and (ii) what that skilled person would reasonably search for, in trying to address the problem faced by the inventor. A court or examiner should therefore consider evidence cited by the parties or the applicant that demonstrates “the knowledge and perspective of a person of ordinary skill in the art at the time of the invention.”

Here, the four references are relevant to the question of whether one skilled in the art of fire prevention and suppression would have reasonably consulted references relating to normal pressure, low-oxygen atmospheres to address the problem of preventing and suppressing fires in enclosed environments. As stated above, the four references—Gustafsson, the 1167 Report, Luria, and Carhart—to which show that “a POSA would have known and appreciated that the breathable hypoxic air produced by Kotliar is fire-preventative and fire-suppressive, even though Kotliar does not state this” (emphasis in original). These references, the CAFC stated, could therefore lead a court or an examiner to conclude that one skilled in the field of fire prevention and suppression would have looked to Kotliar for its disclosure of a hypoxic room, even though Kotliar itself is outside the field of endeavor.

The CAFC therefore vacated the Board’s decision and remanded the case for the Board to consider whether Kotliar is analogous prior art in view of the four references.

Takeaway:

In resolving the “reasonably pertinent” test, courts and examiners must look at all the evidence of record.

Preamble Reciting a Travel Trailer is a Structural Limitation – Avoiding Assertions of Intended Use

| November 26, 2019

In Re: David Fought, Martin Clanton.

November 4, 2019

Newman, Moore and Chen

Summary

This decision provides an excellent example of when a limitation in a preamble is given patentable weight. The decision also illustrates arguments which will not be successful. The Federal Circuit held that not only was the preamble limiting, but also held that a “travel trailer” is considered a specific type of recreation vehicle having structural distinctions.

Background

The patent application contains two independent claims:

1. A travel trailer having a first and second compartment therein separated by a wall assembly which is movable so as to alter the relative dimensions of the first and second compartments without altering the exterior appearance of the travel trailer.

2. A travel trailer having a front wall, rear wall, and two side walls with a first and a second compartment therein, those compartments being separated by a wall assembly, the wall assembly having a forward wall and at least one side member,

the side member being located adjacent to and movable in parallel with respect to a side wall of the trailer, and

the wall assembly being moved along the longitudinal length of the trailer by drive means positioned between the side member and the side wall. (Emphasis added)

The examiner rejected claim 1 as anticipated by a reference describing a conventional truck trailer such as a refrigerated trailer, and rejected claim 2 as anticipated over another reference describing a bulkhead for shipping compartments. The applicants appealed the rejections by (1) arguing that the claims do not have a preamble, (2) arguing that a travel trailer is a type of recreational vehicle, as supported by extrinsic evidence, and (3) arguing that the Examiner erred by rejecting the claims without addressing the level of ordinary skill.

Discussion

The CAFC reviewed the Board’s legal conclusions (involving claim construction) de novo and reviewed the factual findings (involving the extrinsic evidence) for substantial evidence.

The effect of a preamble is treated as a claim construction issue. The CAFC was not persuaded by the argument that the claims do not have a preamble because a traditional transitional phrase such as “comprising” was not used. The CAFC explained that although a traditional transitional phrase was not used, the word “having” performs the role of a transitional phrase. As such, this argument was not persuasive.

The next argument, however, was found persuasive. In particular, the CAFC has repeatedly held that a preamble is limiting when it serves as antecedent basis for a term appearing in the body of the claim. See, e.g., C.W. Zumbiel Co., 702 F.3d at 1385; Bell Commc’ns Re-search, Inc. v. Vitalink Commc’ns Corp., 55 F.3d 615, 620–21 (Fed. Cir. 1995); Electro Sci. Indus., Inc. v. Dynamic De-tails, Inc., 307 F.3d 1343, 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2002); Pacing Techs., LLC v. Garmin Int’l, Inc., 778 F.3d 1021, 1024 (Fed. Cir. 2015). As seen in claims 1 and 2 above, each claim refers back to the preamble.

With respect to the meaning of “travel trailer”, the PTAB quoted relevant portions of the extrinsic evidence:

“Recreational vehicles” or “RVs,” as referred to herein, can be motorized or towed, but in general have a living area which provides shelter from the weather as well as personal conveniences for the user, such as bathroom(s), bedroom(s), kitchen, dining room, and/or family room. Each of these rooms typically forms a separate compartment within the vehicle . . . . A towed recreational vehicle is generally referred to as a “travel trailer.”

Probably the single most-popular class of towable RV is the Travel Trailer. Spanning 13 to 35 feet long, travel trailers are designed to be towed by cars, vans, and pickup trucks with only the addition of a frame or bumper mounted hitch. Single axles are common, but dual and even triple axles may be found on larger units to carry the load.

In regard to the meaning of “travel trailer”, the extrinsic evidence shows that “travel trailer” connotes a specific structure of towability which is not an intended use. In addition, the extrinsic evidence shows that recreational vehicles and travel trailers have living space rather than cargo space, which also is not an intended use. As such, “travel trailer” is a specific type of recreational vehicle and the term is a structural limitation.

The CAFC thus concludes:

“There is no dispute that if “travel trailer” is a limitation, Dietrich and McDougal, which disclose cargo trailers and shipping compartments, do not anticipate. Just as one would not confuse a house with a warehouse, no one would confuse a travel trailer with a truck trailer.”

The argument that the PTAB erred for failing to explicitly state the level of ordinary skill was a loser:

“Unless the patentee places the level of ordinary skill in the art in dispute and explains with particularity how the dispute would alter the outcome, neither the Board nor the examiner need articulate the level of ordinary skill in the art. We assume a proper determination of the level of ordinary skill in the art as required by Phillips.”

Takeaways

- The preamble is limiting when it serves as antecedent basis for a term appearing in the body of the claim.

- A term in the preamble can be construed as a structural limitation and not merely a statement of intended use when the evidence supports such meaning.

Is a claim limitation functional or merely an intended use?

| November 21, 2019

Quest USA Corp. v. PopSockets LLC (Patent Trial and Appeal Board)

August 12, 2019

Zado, Kaiser and Margolies (Administrative Patent Judges)

Summary:

This case is a Final Written Decision by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board of an inter partes review (“IPR”) filed by Quest USA Corp (“Petitioner”) against U.S. Patent No. 8,560,031 owned by PopSockets LLC (“Patent Owner”). One issue in the IPR was whether a limitation in claim 9 of the ‘031 patent is a functional limitation that should be given patentable weight or whether the limitation is just an intended use that is not given patentable weight. The noted limitation is a securing element “for attaching the socket to the back of the portable media player.” As part of its finding that the claims are anticipated, the PTAB held that the noted limitation is an intended use and that Grinfas is inherently capable of satisfying the noted limitation.

Details:

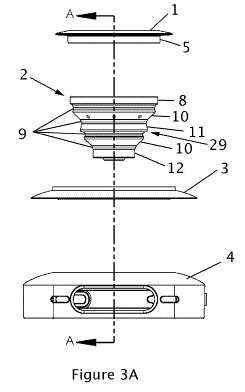

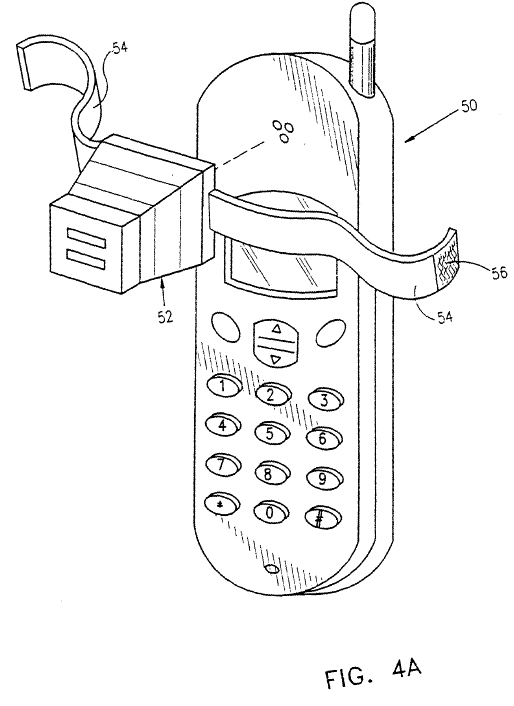

The ‘031 patent is to an “Extending Socket for Portable Media Player” and describes extending sockets for attaching to the back of a portable media player or media player case. The extending sockets can be used for, e.g., storing headphone cords and preventing cords from tangling. Figure 3A from the ‘031 patent is provided:

Claims 9-11, 16 and 17 of the ‘031 patent are at issue in this IPR. Claim 9 is provided below, and the limitation relevant to this summary is highlighted:

9. A socket for attaching to a portable media player or to a portable media player case, comprising:

[a] a securing element for attaching the socket to the back of the portable media player or portable media player case; and

[b] an accordion forming a tapered shape connected to the securing element, the accordion capable of extending outward generally along its [axis] from the portable media player and retracting back toward the portable media player by collapsing generally along its axis; and

[c] a foot disposed at the distal end of the accordion.

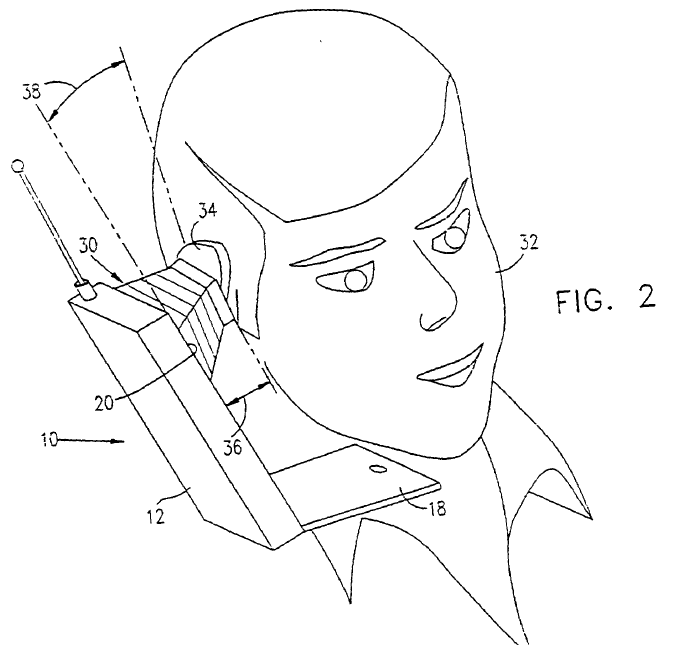

Petitioner asserted that claims 9-11, 16 and 17 are anticipated by Grinfas (UK Patent Application GB 2 316 263 A). Grinfas discloses a collapsible sound conduit for attaching to a cellular telephone. The idea of Grinfas is to provide a spaced distance between the telephone and a user’s head to reduce radiation exposure. Figures 2, 3 and 4A of Grinfas are provided below:

Grinfas discloses using an adhesive pad or straps to attach the collapsible sound conduit to the asserted media player. Patent Owner did not dispute that Grinfas discloses “a securing element” for attaching the socket to the earpiece of a telephone. However, Patent Owner, attempting to characterize the limitation as functional, argued that Grinfas does not disclose a securing element “for attaching the socket to the back of the portable media player” as recited in claim 9.

The PTAB stated that the issue is whether the noted limitation recites “1) functional language that must be given patentable weight, or 2) an intended use that is not limiting.” The PTAB also provided these two legal principles:

(1) “Where all structural elements of a claim exist in a prior art product, and that prior art product is capable of satisfying all functional or intended use limitations, the claimed invention is nothing more than an unpatentable new use for an old product.” Bettcher Indus., Inc. v. Bunzl USA, Inc., 661 F.3d 629, 654 (Fed. Cir. 2011).

(2) “[A] prior art reference may anticipate or render obvious an apparatus claim—depending on the claim language—if the reference discloses an apparatus that is reasonably capable of operating so as to meet the claim limitations, even if it does not meet the claim limitations in all modes of operation.” ParkerVision, 903 F.3d at 1361.

Petitioner argued that the “for attaching” language merely recites an intended use and is not entitled to patentable weight and that the structures disclosed in Grinfas are inherently capable of attaching to the back of a phone or phone case. The PTAB agreed with Petitioner that Grinfas is inherently capable of performing the function of attaching the asserted socket to the back of the portable media player. They relied on expert testimony that stated that the adhesive pad described in Grinfas has an adhesive that would stick to either side of the telephone, and that the straps could be used to fasten the sound conduit to either side of a telephone.

Patent Owner did not dispute that Grinfas’s securing elements are inherently capable of attaching the collapsible sound conduit to the back of a telephone. Patent Owner argued that Grinfas does not actually disclose the function of attaching to the back of a phone, and that the expert failed to provide evidence that the claimed function is necessarily present in Grinfas. The PTAB stated that Petitioner is not required to show the claimed function is actually performed or must be performed.

Patent Owner further argued that the “for attaching the socket to the back” limitation is entitled to patentable weight “because … this language recites a fundamental characteristic without which the invention would be of little use.” However, the PTAB looked at the specification and the prosecution history and concluded that the limitation does not recite a fundamental characteristic without which the invention would be of little use. The PTAB said that the specification did not describe a securing structure as being specific for attaching to the back, as opposed to some other portion, of a portable media player or case. The PTAB further stated that the specification indicates that the invention would be useful when attached to the media player generally, but does not specify attachment to the back as a requirement.

Thus, the PTAB concluded that Grinfas discloses a securing element inherently capable of being attached to the back of a portable media player, and that Grinfas discloses the securing element limitation of claim 9. The PTAB also found that Grinfas discloses all other limitations of claim 9 and that Grinfas anticipates all of the disputed claims.

Comments

The opinion pointed out that there is a risk in choosing to define an element functionally in an apparatus claim. A functional claim limitation in an apparatus claim may be considered as an intended use, and the prior art will satisfy the limitation if it is reasonably capable of performing the function.

The ‘031 patent also included a method claim (claim 16). The method claim recited attaching the socket to a portable media player; selectively extending the socket; and selectively retracting the socket. However, the method claim did not recite attaching the socket to the “back” of the portable media player.

It appears from the PTAB decision that the patent owner may have had a chance to avoid anticipation if they could actually show that the function “recites a fundamental characteristic without which the invention would be of little use.” The decision appears to give weight to the patent owner’s argument that if the function “recites a fundamental characteristic without which the invention would be of little use,” then the prior art must actually disclose performing the function.

Definitely Consisting Essentially Of: Basic and Novel Properties Must Be Definite Under 35 U.S.C. §112

| November 15, 2019

HZNP Medicines, LLC, Horizon Pharma USA, Inc. v. Actavis Laboratories UT, Inc.

October 15, 2019

Before: Prost, Reyna and Newman; Opinion by: Reyna; Dissent-in-part by: Newman

Summary: Horizon appealed a claim construction that the term “consisting essentially of” was indefinite. The district court evaluated the basic and novel properties under the Nautilus definiteness standard and found that the properties set forth in Horizon’s specification where indefinite. Horizon maintained this was legal error. The CAFC found that having used the phrase “consisting essentially of,” Horizon thereby incorporated unlisted ingredients or steps that do not materially affect the basic and novel properties of the invention. They asserted that a drafter cannot later escape the definiteness requirement by arguing that the basic and novel properties of the invention are in the specification, not the claims. Newman dissents, noting that no precedent has held that “consisting essentially of” composition claims are invalid unless they include the properties of the composition in the claims and that the majority’s ruling “sows conflict and confusion.”

Details:

- Background

HZNP Medicines, LLC, Horizon Pharma USA, Inc (“Horizon”) owns a series of patents directed to a methods and compositions for treating osteoarthritis. Actavis Laboratories UT, Inc (“Actavis”) sought to manufacture a generic version. Horizon sued Actavis for infringement in the District of New Jersey. Most of Horizon’s claims were removed by Summary Judgment on multiple issues. One claim survived to trial and was found valid and infringed. The CAFC taking up the appeal and cross-appeal on a number of issues (induced infringement, obviousness of a modified chemical formula and indefiniteness) affirmed the District Court.

This paper focuses on the ruling that Horizon claims using the “consisting essentially of” transitional phrase where invalid based on the basic and novel properties being indefinite under 35 U.S.C. §112.

- The CAFC’s Decision

Several of the claims in the Horizon patents recited a formulation “consisting essentially of” various ingredients. Claim 49 of the ’838 patent was used as the example.

49. A topical formulation consisting essentially of:

1–2% w/w diclofenac sodium;

40–50% w/w DMSO;

23–29% w/w ethanol;

10–12% w/w propylene glycol;

hydroxypropyl cellulose; and

water to make 100% w/w, wherein the topical formulation has a viscosity of 500–5000 centipoise.

The claims had been found invalid by the District Court under Summary Judgement following a Markman hearing. The parties’ dispute focused on the basic and novel properties of the claims. The CAFC agreed with the District Court that these properties are implicated by virtue of the phrase “consisting essentially of,” which allows unlisted ingredients to be added to the formulation so long as they do not materially affect the basic and novel properties.

The district court held that the specification of the patents identified five basic and novel properties: (1) better drying time; (2) higher viscosity; (3) increased transdermal flux; (4) greater pharmacokinetic absorption; and (5) favorable stability. Further, the district court reviewed the characteristics and found that at least “better drying time” was indefinite because the specifications provided two separate manners of determining drying time which were inconsistent. Based thereon, they concluded that the basic and novel properties of the claimed invention were indefinite under Nautilus.

The CAFC evaluated whether the Nautilus definiteness standard applies to the basic and novel properties of an invention. Horizon had argued that the Nautilus definiteness standard focuses on the claims and therefore does not apply to the basic and novel properties of the invention. The majority found this argument to be “misguided” and asserted that by using the phrase “consisting essentially of” in the claims, the inventor in this case incorporated into the scope of the claims an evaluation of the basic and novel properties.

The use of “consisting essentially of” implicates not only the items listed after the phrase, but also those steps (in a process claim) or ingredients (in a composition claim) that do not materially affect the basic and novel properties of the invention. Having used the phrase “consisting essentially of,” and thereby incorporated unlisted ingredients or steps that do not materially affect the basic and novel properties of the invention, a drafter cannot later escape the definiteness requirement by arguing that the basic and novel properties of the invention are in the specification, not the claims.

They supported this position by noting that a patentee can reap the benefit of claiming unnamed ingredients and steps by employing the phrase “consisting essentially of” so long as the basic and novel properties of the invention are definite.

In evaluating the district courts finding of indefiniteness, the CAFC maintained that two questions arise when claims use the phrase “consisting essentially of.” The first focusing on definiteness: “what are the basic and novel properties of the invention?” The second, focusing on infringement: “does a particular unlisted ingredient materially affect those basic and novel properties?” The definiteness inquiry focuses on whether a person of ordinary skill in the art (“POSITA”) is reasonably certain about the scope of the invention. If the POSITA cannot as-certain the bounds of the basic and novel properties of the invention, then there is no basis upon which to ground the analysis of whether an unlisted ingredient has a material effect on the basic and novel properties. Keeping with this logic, the CAFC maintained that to determine if an unlisted ingredient materially alters the basic and novel properties of an invention, the Nautilus definiteness standard requires that the basic and novel properties be known and definite.

Hence, the CAFC concluded that the district court did not err in considering the definiteness of the basic and novel properties during claim construction.

The majority then looked to the specific finding of indefiniteness by the district court regarding the basic and novel property of “better drying time.” They noted that the specification discloses results from two tests: an in vivo test and an in vitro test. The district court had found that the two different methods for evaluating “better drying time” do not provide consistent results at consistent times. Accordingly, CAFC affirmed the district court’s conclusion that the basic and novel property of “better drying rate” was indefinite, and consequently, that the term “consisting essentially of” was likewise indefinite.

In sum, we hold that the district court did not err in: (a) defining the basic and novel properties of the formulation patents; (b) applying the Nautilus definiteness standard to the basic and novel properties of the formulation patents; and (c) concluding that the phrase “consisting essentially of” was indefinite based on its finding that the basic and novel property of “better drying time” was indefinite on this record.

However, they noted that the Nautilus standard was not to be applied in an overly stringent manner.

To be clear, we do not hold today that so long as there is any ambiguity in the patent’s description of the basic and novel properties of its invention, no matter how marginal, the phrase “consisting essentially of” would be considered indefinite. Nor are we requiring that the patent owner draft claims to an untenable level of specificity. We conclude only that, on these particular facts, the district court did not err in determining that the phrase “consisting essentially of” was indefinite in light of the indefinite scope of the invention’s basic and novel property of a “better drying time.”

Judge Newman’s Dissent

Judge Newman dissented. She asserted that the majority holding that “By using the phrase ‘consisting essentially of’ in the claims, the inventor in this case incorporated into the scope of the claims an evaluation of the basic and novel properties” is not correct as a matter of claim construction, it is not the law of patenting novel compositions, and it is not the correct application of section 112(b).

First, she noted that there is no precedent that when the properties of a composition are described in the specification, the usage “consisting essentially of” the ingredients of the composition invalidates the claims when the properties are not repeated in the claims.

Second, in regard to the specifics of “drying time” for the case at hand, she noted that whatever the significance of drying time as an advantage of the claimed composition, recitation and measurement of this property in the specification does not convert the composition claims into invalidating indefiniteness because the ingredients are listed in the claims as “consisting essentially of.”

The role of the claims is to state the subject matter for which patent rights are sought. The usage “consisting essentially of” states the essential ingredients of the claimed composition. There are no fuzzy concepts, no ambiguous usages in the listed ingredients. There is no issue in this case of the effect of other ingredients…

Noting that there was no evidence that a POSITA would not understand the components of the composition claims with reasonable certainty, Newman concluded that since in the current case there are no other components asserted to be present, no “unnamed ingredients and steps” that even adopting the construction taken by the majority the claims are not subject to invalidity for indefiniteness.

Takeaways:

Added caution must be taken by patent prosecutors when electing to use the transitional phrase “consisting essentially of”. The specification needs to be clear as to what the basic and novel properties are and how they are determinable.

When using “consisting essentially of” incorporating the properties that are considered to be basic and novel into the claim language may help prevent ambiguity.

Tags: 35 U.S.C. §112 > basic and novel properties > consisting essentially of > definiteness

Presenting multiple arguments in prosecution risks prosecution history estoppel on each of them

| November 8, 2019

Amgen Inc. v. Coherus BioSciences Inc.

July 29, 2019

Before Reyna, Hughes, and Stoll. Opinion by Stoll.

Summary

The CAFC affirmed a district court decision holding that Amgen had failed to state a claim and dismissed Amgen’s suit against Coherus for patent infringement under the doctrine of equivalents, in view of Amgen’s clear and unmistakable disclaimer of claim scope during prosecution.

Details

Amgen Inc. and Amgen Manufacturing Ltd. (“Amgen”) sued Coherus BioSciences Inc. for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 8,273,707 (the ‘707 patent). The patent relates to methods of purifying proteins using hydrophobic interaction chromatography (“HIC”), in which a buffered salt solution containing the desired protein is poured into a HIC column and the proteins are bound to a column matrix while the impurities are washed out. However, only a limited amount of protein can bind to the matrix. If too much protein is loaded on the column, some of the protein will be lost to the solution phase before elution.

Conventionally, a higher salt concentration in a buffer solution is provided to increase the dynamic capacity of the HIC column, but the higher salt concentration causes protein instability. Amgen’s ‘707 patent discloses a process that increases the dynamic capacity of a HIC column by providing combinations of salts instead of using a single salt.

According to the ‘707 patent, any one of the three combinations of salts – citrate and sulfate, citrate and acetate, or sulfate and acetate – allows for a decreased concentration of at least one of the salts to achieve a greater dynamic capacity without compromising the quality of the protein separation.

During prosecution, the Examiner rejected the claims as being obvious in view of U.S. Patent No. 5,231,178 (“Holtz”). In reply to the Examiner’s rejection, Amgen argued that:

(1) The pending claims recite a particular combination of salts. No combinations of salts are taught nor suggested in Holtz;

(2) No particular combinations of salts recited in the pending claims are taught or suggested in Holtz; and

(3) Holtz does not teach dynamic capacity at all.

Amgen also attached a declaration from the inventor. The declaration stated that the use of the three salt combinations leads to substantial increases in the dynamic capacity of a HIC column and “[use] of this particular combination of salts greatly improves the cost-effectiveness of commercial manufacturing by reducing the number of cycles required for each harvest and reducing the processing time for each harvest.”

The Examiner again rejected Amgen’s argument and took the position that the prior art does disclose salts used in a method of purification and that adjustment of conditions was within the skill of an ordinary artisan. This time, in response to the Examiner’s position, Amgen replied that Holtz does not disclose any combination of salts and does not mention the dynamic capacity of a HIC column. In particular, Amgen stated that it was a “lengthy development path” when choosing a working salt combination and that merely adding a second salt would not have been expected to result in the invention. The Examiner allowed the claims.

In 2016, Coherus sought FDA approval to market a biosimilar version of Amgen’s pegfilgrastim product. In 2017, Amgen sued Coherus for infringing the ‘707 patent under the doctrine of equivalents because Coherus’s process did not match any of the three explicitly recited salt combinations in the ‘707 patent. Coherus moved to dismiss Amgen’s complaint for failure to state a claim.

The district court agreed to dismiss the complaint. The district court noted that during prosecution, Amgen had distinguished Holtz by repeatedly arguing that Holtz did not disclose “one of the particular, recited combinations of salts” in the two responses and in the declaration. The district court held that “[t]he prosecution history, namely, the patentee’s correspondence in response to two office actions and a final rejection, shows a clear and unmistakable surrender of claim scope by the patentee.” In addition, the district court held that “by disclosing but not claiming the salt combination used by Coherus, Amgen had dedicated that particular combination to the public.”

Amgen appealed.

The CAFC affirmed the district Court’s dismissal and found that the “prosecution history estoppel has barred Amgen from succeeding on its infringement claim under the doctrine of equivalents.”

In the appeal, Amgen argued that it only had distinguished Holtz by stating that Holtz does not disclose increasing any dynamic capacity or mention any salt combination. Amgen also argued that the prosecution history should not apply here because the last response filed prior to allowance did not make the argument that Holtz failed to disclose the particular salt combinations.

Regarding Amgen’s first point – that during prosecution, only dynamic capacity had been used to distinguish Holtz – the CAFC noted the three grounds on which Amgen has relied for distinguishing Holtz, and the fact that Amgen had quoted the declaration in support of the particular combination of salts recited in the claims. The CAFC explained that “separate arguments create separate estoppels as long as the prior art was not distinguished based on the combination of these various grounds.”

The CAFC also disagreed with Amgen’s second point (that prosecution history estoppel should not apply because of their last response), commenting that “there is no requirement that argument-based estoppel apply only to arguments made in the most recent submission before allowance… We see nothing in Amgen’s final submission that disavows the clear and unmistakable surrender of unclaimed salt combinations made in Amgen’s response.”

The CAFC held that the prosecution history estoppel applied and affirmed the District Court’s order dismissing Amgen’s complaint for failure to state a claim. The CAFC did not discuss whether Amgen dedicated unclaimed salt combinations to the public.

Takeaway

- Prosecution history estoppel can be triggered, not only by narrowing amendments, but also by arguments, even without any amendments.

- Presenting multiple arguments does not eliminate the risk of triggering estoppel for each of them.

- When writing an argument, avoid using expressions that are not recited in the claims (when discussing the claimed invention) or the cited documents (when discussing the state of the art).

The CAFC’s Holding that Claims are Directed to a Natural Law of Vibration and, thus, Ineligible Highlights the Shaky Nature of 35 U.S.C. 101 Evaluations

| November 1, 2019

American Axle & Manufacturing, Inc. v. Neapco Holdings, LLC

October 9, 2019

Opinion by: Dyke, Moore and Taranto (October 3, 2019).

Dissent by: Moore.

Summary:

American Axle & Manufacturing, Inc. (AAM) sued Neapco Holdings, LLC (Neapco) for alleged infringement of U.S. Patent 7,774,911 for a method of manufacturing driveline propeller shafts for automotive vehicles. On appeal, the Federal Circuit upheld the District Court of Delaware’s holding of invalidity under 35 U.S.C. 101. The Federal Circuit explained that the claims of the patent were directed to the desired “result” to be achieved and not to the “means” for achieving the desired result, and, thus, held that the claims failed to recite a practical way of applying underlying natural law (e.g., Hooke’s law related to vibration and damping), but were instead drafted in a results-oriented manner that improperly amounted to encompassing the natural law.

Details:

- Background

The case relates to U.S. Patent 7,774,911 of American Axle & Manufacturing, Inc. (AAM) which relates to a method for manufacturing driveline propeller shafts (“propshafts”) with liners that are designed to attenuate vibrations transmitted through a shaft assembly. Propshafts are employed in automotive vehicles to transmit rotary power in a driveline. During use, propshafts are subject to excitation or vibration sources that can cause them to vibrate in three modes: bending mode, torsion mode, and shell mode.

The CAFC focused on independent claims 1 and 22 as being “representative” claims, noting that AAM “did not argue before the district court that the dependent claims change the outcome of the eligibility analysis.”

| Claim 1 | Claim 22 |

| 1. A method for manufacturing a shaft assembly of a driveline system, the driveline system further including a first driveline component and a second driveline component, the shaft assembly being adapted to transmit torque between the first driveline component and the second driveline component, the method comprising: providing a hollow shaft member; tuning at least one liner to attenuate at least two types of vibration transmitted through the shaft member; and positioning the at least one liner within the shaft member such that the at least one liner is configured to damp shell mode vibrations in the shaft member by an amount that is greater than or equal to about 2%, and the at least one liner is also configured to damp bending mode vibrations in the shaft member, the at least one liner being tuned to within about ±20% of a bending mode natural frequency of the shaft assembly as installed in the driveline system. | 22. A method for manufacturing a shaft assembly of a driveline system, the driveline system further including a first driveline component and a second driveline component, the shaft assembly being adapted to transmit torque between the first driveline component and the second driveline component, the method comprising: providing a hollow shaft member; tuning a mass and a stiffness of at least one liner, and inserting the at least one liner into the shaft member; wherein the at least one liner is a tuned resistive absorber for attenuating shell mode vibrations and wherein the at least one liner is a tuned reactive absorber for attenuating bending mode vibrations. |

As explained by the CAFC, “[i]t was known in the prior art to alter the mass and stiffness of liners to alter their frequencies to produce dampening,” and “[a]ccording to the ’911 patent’s specification, prior art liners, weights, and dampers that were designed to individually attenuate each of the three propshaft vibration modes — bending, shell, and torsion — already existed.” The court further explained that in the ‘911 patent “these prior art damping methods were assertedly not suitable for attenuating two vibration modes simultaneously,” i.e., “shell mode vibration [and] bending mode vibration,” but “[n]either the claims nor the specification [of the ‘911 patent] describes how to achieve such tuning.”

The District Court concluded that the claims were directed to laws of nature: Hooke’s law and friction damping. And, the District Court held that the claims were ineligible under 35 U.S.C. 101. AAM appealed.

- The CAFC’s Decision

Under 35 U.S.C. 101, “any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof” may be eligible to obtain a patent, with the exception long recognized by the Supreme Court that “laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas are not patentable.”

Under the Supreme Court’s Mayo and Alice test, a 101 analysis follows a two-step process. First, the court asks whether the claims are directed to a law of nature, natural phenomenon, or abstract idea. Second, if the claims are so directed, the court asks whether the claims embody some “inventive concept” – i.e., “whether the claims contain an element or combination of elements that is sufficient to ensure that the patent in practice amounts to significantly more than a patent upon the ineligible concept itself.”

At step-one, the CAFC explained that to determine what the claims are directed to, the court focuses on the “claimed advance.” In that regard, the CAFC noted that the ‘911 patent discloses a method of manufacturing a driveline propshaft containing a liner designed such that its frequencies attenuate two modes of vibration simultaneously. The CAFC also noted that AAM “agrees that the selection of frequencies for the liners to damp the vibrations of the propshaft at least in part involves an application of Hooke’s law, which is a natural law that mathematically relates mass and/or stiffness of an object to the frequency that it vibrates. However, the CAFC also noted that “[a]t the same time, the patent claims do not describe a specific method for applying Hooke’s law in this context.”

The CAFC also noted that “even the patent specification recites only a nonexclusive list of variables that can be altered to change the frequencies,” but the CAFC emphasized that “the claims do not instruct how the variables would need to be changed to produce the multiple frequencies required to achieve a dual-damping result, or to tune a liner to dampen bending mode vibrations.”

The CAFC explained that “the claims general instruction to tune a liner amounts to no more than a directive to use one’s knowledge of Hooke’s law, and possibly other natural laws, to engage in an ad hoc trial-and-error process … until a desired result is achieved.”

The CAFC explained that the “distinction between results and means is fundamental to the step 1 eligibility analysis, including law-of-nature cases.” The court emphasized that “claims failed to recite a practical way of applying an underlying idea and instead were drafted in such a results-oriented way that they amounted to encompassing the [natural law] no matter how implemented.

At step-two, the CAFC stated that “nothing in the claims qualifies as an ‘inventive concept’ to transform the claims into patent eligible matter.” The CAFC explained that “this direction to engage in a conventional, unbounded trial-and-error process does not make a patent eligible invention, even if the desired result … would be new and unconventional.” As the claims “describe a desired result but do not instruct how the liner is tuned to accomplish that result,” the CAFC affirmed that the claims are not eligible under step two.

NOTE: In response to Judge Moore’s dissent, the CAFC explained that the dissent “suggests that the failure of the claims to designate how to achieve the desired result is exclusively an issue of enablement.” However, the CAFC expressed that “section 101 serves a different function than enablement” and asserted that “to shift the patent-eligibility inquiry entirely to later statutory sections risks creating greater legal uncertainty, while assuming that those sections can do work that they are not equipped to do.”

- Judge Moore’s Dissent

Judge Moore strongly dissented against the majority’s opinion. Judge Moore argued, for example, that:

- “The majority’s decision expands § 101 well beyond its statutory gate-keeping function and the role of this appellate court well beyond its authority.”

- “The majority’s concern with the claims at issue has nothing to do with a natural law and its preemption and everything to do with concern that the claims are not enabled. Respectfully, there is a clear and explicit statutory section for enablement, § 112. We cannot convert § 101 into a panacea for every concern we have over an invention’s patentability.”

- “Section 101 is monstrous enough, it cannot be that now you need not even identify the precise natural law which the claims are purportedly directed to.” “The majority holds that they are directed to some unarticulated number of possible natural laws apparently smushed together and thus ineligible under § 101.”

- “The majority’s validity goulash is troubling and inconsistent with the patent statute and precedent. The majority worries about result-oriented claiming; I am worried about result-oriented judicial action.”

Takeaways:

- When drafting claims, be mindful to avoid drafting a “result-oriented” claim that merely recites a desired “result” of a natural law or natural phenomenon without including specific steps or details setting establishing “how” the results are achieved.

- When drafting claims, be mindful that although under 35 U.S.C. 112 supportive details satisfying enablement are only required to be within the written specification, under 35 U.S.C. 101 supportive details satisfying eligibility must be within the claims themselves.