The Federal Circuit declined to be bound by the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance by the Patent Office, but affirmed the Board’s conclusion of the ineligibility, which relied on the Guidance

| May 7, 2020

In re Rudy

April 24, 2020

Prost, Chief Judge, O’Malley and Taranto. Court opinion by Prost.

Summary

The Federal Circuit declined to be bound by the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance by the Patent Office, and instead followed the Supreme Court’s Alice/Mayo framework, and the Federal Circuit’s interpretation and application thereof. However, the Federal Circuit unanimously affirmed the Board’ affirmance of the Examiner’s rejection of claims 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, and 45–49 of the ’360 application as patent-ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101, which was fully relied on the Office Guidance.

Details

I. background

United States Patent Application No. 07/425,360 (“the ’360 application”), filed by Christopher Rudy on October 21, 1989 (before the signing of the 1994 Uruguay Round Agreements Act), is entitled “Eyeless, Knotless, Colorable and/or Translucent/Transparent Fishing Hooks with Associatable Apparatus and Methods.” After a lengthy prosecution of more than twenty years, including numerous amendments and petitions, four Board appeals, and a previous trip to the Federal Circuit where the obviousness of all claims then on appeal was affirmed (In re Rudy, 558 F. App’x. 1011 (Fed. Cir. 2014) (non-precedential)), claim 34, which the Board considered illustrative, reads as follows:

34. A method for fishing comprising steps of

(1) observing clarity of water to be fished to deter- mine whether the water is clear, stained, or muddy,

(2) measuring light transmittance at a depth in the water where a fishing hook is to be placed, and then

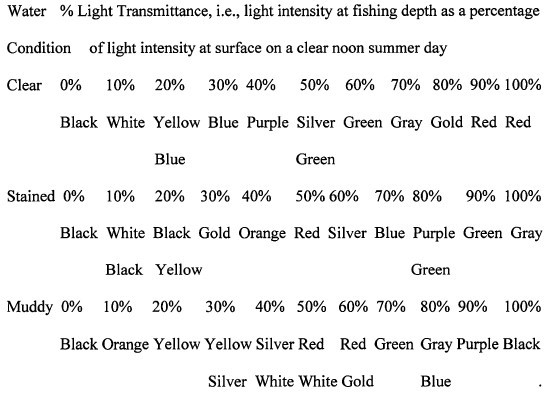

(3) selecting a colored or colorless quality of the fishing hook to be used by matching the observed water conditions ((1) and (2)) with a color or colorless quality which has been previously determined to be less attractive under said conditions than has undergone those pointed out by the following correlation for fish-attractive non-fluorescent colors:

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) affirmed the Examiner’s rejection of claims 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, and 45–49 of the ’360 application in the last Board appeal. The Board conducted its analysis under a dual framework for patent eligibility, purporting to apply both 1) “the two-step framework described in Mayo [Collaborative Ser- vices v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 566 U.S. 66 (2012)] and Alice [Corp. v. CLS Bank International, 573 U.S. 208 (2014)],” and 2) the 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance, 84 Fed. Reg. 50 (Jan. 7, 2019) (“Office Guidance”), published by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“Patent Office”). Specifically, the Board concluded “[u]nder the first step of the Alice/Mayo framework and Step 2A, Prong 1, of [the] Office Guidelines” that claim 34 is directed to the abstract idea of “select[ing] a colored or colorless quality of a fishing hook based on observed and measured water conditions, which is a concept performed in the human mind.” The Board went on to conclude that “[u]nder the second step in the Alice/Mayo framework, and Step 2B of the 2019 Revised Guidance, we determine that the claim limitations, taken individually or as an ordered combination, do not amount to significantly more than” the abstract idea.

Mr. Rudy timely appealed, challenging both the Board’s reliance on the Office Guidance, and the Board’s ultimate conclusion that the claims are not patent eligible.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit unanimously affirmed the Board’ affirmance of the Examiner’s rejection of claims 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, and 45–49 of the ’360 application.

1. Office Guidance vs. Case Law

Mr. Rudy contended that the Board “misapplied or refused to apply . . . case law” in its subject matter eligibility analysis and committed legal error by instead applying the Office Guidance “as if it were prevailing law.”

The Federal Circuit agreed with Mr. Rudy, stating: “[w]e are not[] bound by the Office Guidance, which cannot modify or supplant the Supreme Court’s law regarding patent eligibility, or our interpretation and application thereof.” Interestingly, the Federal cited a non-precedential opinion to support its position: “As we have previously explained:

While we greatly respect the PTO’s expertise on all matters relating to patentability, including patent eligibility, we are not bound by its guidance. And, especially regarding the issue of patent eligibility and the efforts of the courts to determine the distinction between claims directed to [judicial exceptions] and those directed to patent-eligible ap- plications of those [exceptions], we are mindful of the need for consistent application of our case law.

Cleveland Clinic Found. v. True Health Diagnostics LLC, 760 F. App’x. 1013, 1020 (Fed. Cir. 2019) (non-precedential). ”

In conclusion, the Federal Circuit declared: “[t]o the extent the Office Guidance contradicts or does not fully accord with our caselaw, it is our caselaw, and the Supreme Court precedent it is based upon, that must control.”

2. Subject Matter Eligibility of Rudy’s Case

The Federal Circuit concluded that although a portion of the Board’s analysis is framed as a recitation of the Office Guidance, the Board’s reasoning and conclusion for Rudy’s case are nevertheless fully in accord with the relevant caselaw in this particular case.

To determine whether a patent claim is ineligible subject matter, the U.S. Supreme Court has established a two-step Alice/Mayo framework. In Step One, courts must determine whether the claims at issue are directed to a patent-ineligible concept such as an abstract idea. Alice, 573 U.S. at 208. In Step Two, if the claims are directed to an abstract idea, the courts must “consider the elements of each claim both individually and ‘as an ordered combination’ to determine whether the additional elements ‘transform the nature of the claim’ into a patent-eligible application.” Id. To transform an abstract idea into a patent-eligible application, the claims must do “more than simply stat[e] the abstract idea while adding the words ‘apply it.’” Id. at 221. At each step, the claims are considered as a whole. See id. at 218 n.3, 225.

a. Step One

With respect to claim 34, the Federal Circuit concluded, as the Board did, that the claim is directed to the abstract idea of selecting a fishing hook based on observed water conditions. Specifically, the Federal Circuit compared claim 34 with Elec. Power Grp., and reasoned that claim 34 requires nothing more than collecting information (water clarity and light transmittance) and analyzing that information (by applying the chart included in the claim), which collectively amount to the abstract idea of selecting a fishing hook based on the observed water conditions. See Elec. Power Grp., LLC v. Alstom S.A., 830 F.3d 1350, 1353–54 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (the Federal Circuit held in the computer context that “collecting information” and “analyzing” that information are within the realm of abstract ideas.).

The Federal Circuit disagreed with Mr. Rudy’s contention that claim 34’s preamble, “a method for fishing,” is a substantive claim limitation such that each claim requires actually attempting to catch a fish by placing the selected fishing hook in the water. The Federal Circuit reasoned that such an “additional limitation,” even if that were true, would not alter the conclusion because the character of claim 34 as a whole remains directed to an abstract idea.

The Federal Circuit also disagreed with Mr. Rudy’s contention that claim 34 is not directed to an abstract idea both because fishing “is a practical technological field . . . recognized by the PTO” and because he contends that observing light transmittance is unlikely to be performed mentally. Regarding the “practical technological field,” the Court reasoned that the undisputed fact that an applicant can obtain subject-matter eligible claims in the field of fishing is irrelevant to the fact that the claims currently before the Court are not eligible. Regarding the unlikeliness of the mental performance, the Court pointed our that the plain language of the claims encompasses such mental determination.

The Federal Circuit further rejected Mr. Rudy’s contention that, relying on the machine-or-transformation test, practicing claim 34 “acts upon or transforms fish” by transforming “freely swimming fish to hooked and landed fish” or by transforming a fishing hook “from one not having a target fish on it to one dressed with a fish when a successful strike ensues.” The Court declined to decide in this case whether the transformation from free fish to hooked fish is the type of transformation discussed in Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593, 604 (2010) and its predecessor cases. Instead, the Court stated that claim 34 does not actually recite or require the purported transformation that Mr. Rudy relies upon because, as Mr. Rudy’s explained, “landing a fish is never a sure thing. Many an angler has gone fishing and returned empty handed.”

b. Step Two

In the Step Two Analysis, the Court concluded that claim 34 fails to recite an inventive concept at step two of the Alice/Mayo test, and is thus not patent eligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101 because the three elements of the claim (observing water clarity, measuring light transmittance, and selecting the color of the hook to be used), either individually or as an ordered combination, do not amount to “‘significantly more than a patent upon the ineligible concept itself.’” The argument in the Step Two Analysis appears somewhat cursory.

c. The Remaining Claims

The Federal Circuit concluded that claim 38, the only other independent claim on appeal, is not patent-eligible as well.

Claim 38 begins with a method that is substantively identical to claim 34, but includes a slightly different chart for selecting the fishing hook color, and further includes only one additional limitation, which recites: “wherein the fishing hook used is disintegrated from but is otherwise connectable to a fishing lure or other tackle and has a shaft portion, a bend portion connected to the shaft portion, and a barb or point at the terminus of the bend, and wherein the fishing hook used is made of a suitable material, which permits transmittance of light therethrough and is colored to colorless in nature.”

The Court stated that the slightly different substance of claim 38’s chart does not render it patent eligible because the substance of claim 34’s hook color chart was not the basis of the eligibility determination. The Court further stated that its step-one analysis of claim 34 is equally applicable to claim 38 because, as described above, this limitation does not change the fact that the character of the claim, as a whole, is directed to an abstract idea.

The Court also affirmed the Board’s conclusions that dependent claims 35, 37, and 40 are not patent eligible, as each recites the physical attributes of the connection between the fishing hook and the fishing lure in ways not meaningfully distinct from claim 38.

The Court further affirm the Board’s conclusions regarding claims 45–49, which differ from the previously discussed claims only in that they mandate a specific color of fishing hook, which neither changes the character of the claims as a whole, nor provides an inventive concept distinct from the abstract idea itself.

Takeaway

· The case demonstrates that courts still stick to the comparative approach in Alice step one, instead of defining or categorizing the “abstract idea.” This approach is notably in contrast with that of the Patent Office, which follows the Office Guidance, dividing Alice step one into two inquiries: (i) evaluate whether the claim recites a judicial exception; and (ii) evaluate whether the judicial exception is integrated into a practical application if the claim recites a judicial exception.

· To be on the safe side for the purpose of drafting a patent specification including claim(s), which is robust to an invalidity defense under 35 U.S.C. § 101, the Supreme Court’s law regarding patent eligibility, and the Federal Circuit’s interpretation and application thereof, not the Office Guidance, shall be relied on.

When there is competing evidence as to whether a prior art reference is a proper primary reference, an invalidity decision cannot be made as a matter of law at summary judgment

| April 29, 2020

Spigen Korea Co., Ltd. v. Ultraproof, Inc., et al.

April 17, 2020

Newman, Lourie, Reyna (Opinion by Reyna; Dissent by Lourie)

Summary

Spigen Korea Co., Ltd. (“Spigen”) sued Ultraproof, Inc. (“Ultraproof”) for infringement of its multiple patents directed to designs for cellular phone cases. The district court held that as a matter of law, Spigen’s design patents were obvious over prior art references, and granted Ultraproof’s motion for summary judgment of invalidity. However, based on the competing evidence presented by the parties, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the “CAFC”) reversed and remanded, holding that a reasonable factfinder could conclude that a genuine dispute of material fact exists as to whether the primary reference was proper.

原告Spigen社は、自身の所有する複数の携帯電話ケースに関する意匠特許を被告Ultraproof社が侵害しているとして、提訴した。地裁は、原告の意匠特許は、先行技術文献により自明であるとして、裁判官は被告のサマリージャッジメントの申し立てを容認した。しかしながら、連邦控訴巡回裁判所(CAFC)は、双方の提示している証拠には「重要な事実についての真の争い(genuine dispute of material fact)」があるとして、地裁の判決を覆し、事件を差し戻した。

Details

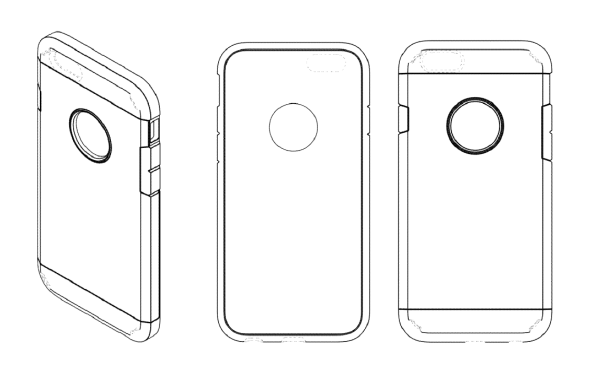

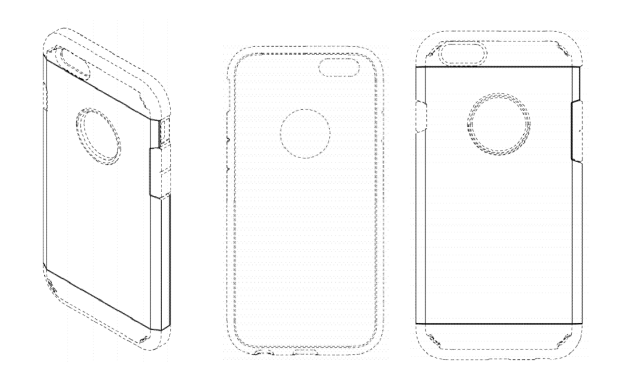

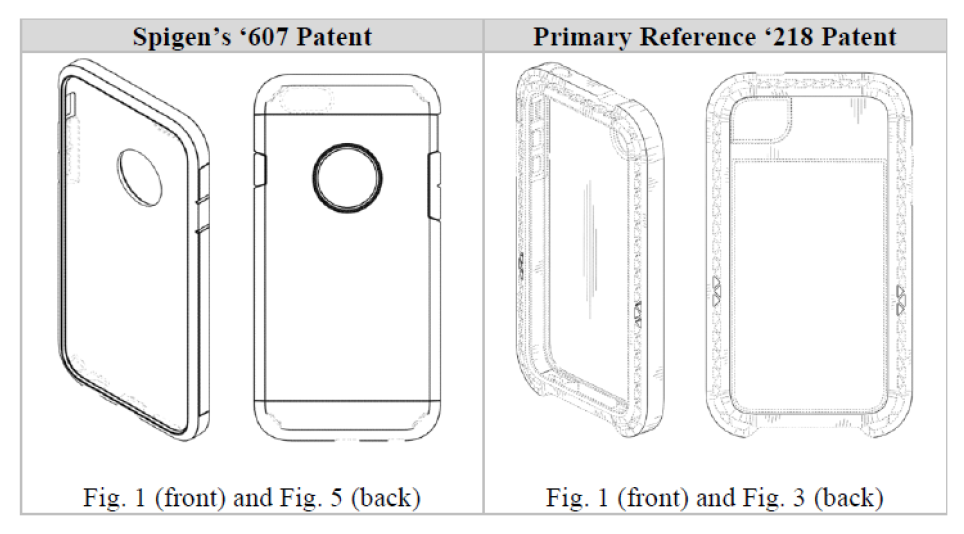

Spigen is the owner of U.S. Design Patent Nos. D771,607 (“the ’607 patent”), D775,620 (“the ’620 patent”), and D776,648 (“the ’648 patent”) (collectively the “Spigen Design Patents”), each of which claims a cellular phone case. Figures 3-5 of the ’607 patent are as shown below:

The ’620 patent disclaims certain elements shown in the ’607 patent, and Figures 3-5 of the ’620 patent are shown below:

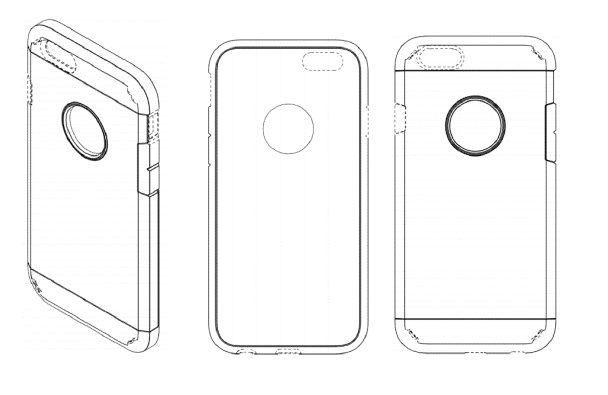

Finally, the ’648 patent disclaims most of the elements present in the ’620 patent and the ’607 patent, Figures 3-5 of which are shown below:

On February 13, 2017, Spigen sued Ultraproof for infringement of Spigen Design Patents in the United States District Court for the Central District of California. Ultraproof filed a motion for summary judgment of invalidity of Spigen Design Patents, arguing that the Spigen Design Patents were obvious as a matter of law in view of a primary reference, U.S. Design Patent No. D729,218 (“the ’218 patent”) and a secondary reference, U.S. Design Patent No. D772,209 (“the ’209 patent”). Spigen opposed the motion arguing that 1) the Spigen Design Patents were not rendered obvious by the primary and secondary reference as a matter of law; and 2) various underlying factual disputes precluded summary judgment. The district court held that as a matter of law, the Spigen Design Patents were obvious over the ’218 patent and the ’209 patent, and granted summary judgment of invalidity in favor of Ultraproof. Ultraproof then moved for attorneys’ fees, which the district court denied. Spigen appealed the district court’s obviousness determination, and Ultraproof cross-appealed the denial of attorneys’ fees.

On appeal, Spigen presented several arguments as to why the district court’s grant of summary judgment should be reversed. First, Spigen argued that there is a material factual dispute over whether the ’218 patent is a proper primary reference that precludes summary judgment. The CAFC agreed. The CAFC explained, citing Titan Tire Corp. v. Case New Holland, Inc., 566 F.3d 1372, 1380-81 (Fed. Cir. 2009) (quoting Durling v. Spectrum Furniture Co., 101 F.3d 100, 103 (Fed. Cir. 1996)) that the ultimate inquiry for obviousness “is whether the claimed design would have been obvious to a designer of ordinary skill who designs articles of the type involved,” which is a question of law based on underlying factual findings. Whether a prior art design qualifies as a “primary reference” is an underlying factual issue. The CAFC went on to explain that a “primary reference” is a single reference that creates “basically the same” visual impression, and for a design to be “basically the same,” the designs at issue cannot have “substantial differences in the[ir] overall visual appearance[s].” Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 678 F.3d 1314, 1330 (Fed. Cir. 2012). A trial court must deny summary judgment if based on the evidence before the court, a reasonable jury could find in favor of the non-moving party. Here, the district court errored in finding that the ’218 patent was “basically the same” as the Spigen Design Patents despite there being “slight differences,” as a reasonable factfinder could find otherwise.

Spigen’s expert testified that the Spigen Design Patents and the ’218 patent are not “at all similar, let alone ‘basically the same.’” Spigen’s expert noted that the ’218 patent has the following features that are different from the Spigen Design Patents:

- unusually broad front and rear chamfers and side surfaces

- substantially wider surface

- lack of any outer shell-like feature or parting lines

- lack of an aperture on its rear side

- presence of small triangular elements illustrated on its chamfers

In contrast, Ultraproof argued that the ’218 patent was “basically the same” because of the presence of the following features:

- a generally rectangular appearance with rounded corners

- a prominent rear chamfer and front chamfer

- elongated buttons corresponding to the location of the buttons of the underlying phone

Ultraproof stated that the only differences were the “circular cutout in the upper third of the back surface and the horizontal parting lines on the back and side surfaces.”

Based on the competing evidence in the record, the CAFC found that a reasonable factfinder could conclude that the ’218 patent and the Spigen Design Patents are not basically the same. T

The CAFC determined that a genuine dispute of material fact exists as to whether the ’218 patent is a proper primary reference, and therefore, reversed the district court’s grant of summary judgment of invalidity and remanded the case for further proceedings.

Takeaway

When there is competing evidence in the record, the determination of whether a prior art reference creates “basically the same” visual impression, and therefore a proper primary reference, is a matter that cannot be decided at summary judgment.

A Patent Claim Is Not Indefinite If the Patent Informs the Relevant Skilled Artisan about the Invention’s Scope with Reasonable Certainty

| April 23, 2020

NEVRO CORP. v. BOSTON SCIENTIFIC

April 9, 2020

Before MOORE, TARANTO, and CHEN, Circuit Judges. MOORE, Circuit Judge

中文标题

权利要求的不确定性判定

中文摘要

内夫罗公司(Nevro)起诉波士顿科学公司和波士顿科学神经调节公司(合称波士顿科学)侵犯了内夫罗公司的七项专利。 内夫罗公司对地方法院的专利无效判决提出上诉。根据专利说明书及其申请历史,联邦巡回法院认定“paresthesia-free,” “configured to,” “means for generating,” 和 “therapy signal” 等术语并未使内夫罗公司的权利要求产生不确定性,因此撤销专利无效判决并发回重审。

小结

- 仅因其为功能用语或仅通过专利权利的诠释不能将功能性语言判定为不确定。

- 功能性语言的确定性重要体现在专利说明书中需要有解释或支持功能术语的相关结构,特别是侧重方法的专利申请,如果这些申请中存在着系统或设备的权利要求, 而这些系统或设备权利要求由方法的权利要求转化而来,对系统或设备的必要描述是需要的。1

- 不确定性的判定标准存在于是否权利要求通过说明书和申请历史以合理的确定性向本领域技术人员告知了本发明的范围。

注1:许多专利申请通常使用诸如“模块”(module)和“单元”(unit)的术语,并将方法权利要求转换为系统或设备的权利要求。但是,在说明书中如果没有相关的结构说明,由于不确定性,通常这些权利要求会被拒绝。因此,专利说明书中有必要对“模块”或“单元”进行必要的描述,例如电子、通讯及软件类的专利申请,可添加一些与通用处理器,集成芯片或现场可编程门阵列有关的描述,以定义“模块”或“单元”并描述相关功能。

Summary

Nevro Corporation (Nevro) sued Boston Scientific Corporation and Boston Scientific Neuromodulation Corporation (collectively, Boston Scientific) for infringement of eighteen claims across seven patents. Nevro Corporation appealed the district court’s judgment of invalidity. The Federal Circuit found that the terms “paresthesia-free,” “configured to,” “means for generating,” and “therapy signal” are not rendering the asserted claims indefinite in view of the specifications and prosecution history, vacating and remanding the district court’s judgment of claim invalidity.

Background

Nevro owns seven patents having method and system claims directed to high-frequency spinal cord stimulation therapy for inhibiting an individual pain. Nevro sued Boston Scientific in the Northern District of California for patent infringement related to U.S. Patent Nos. 8,359,102; 8,712,533; 8,768,472; 8,792,988; 9,327,125; 9,333,357; and 9,480,842.

In a joint claim construction and summary judgment order, the district court held twelve claims invalid as indefinite. Though six asserted claims survived and were found definite, the district court granted Boston Scientific noninfringement. On appeal, the Federal Circuit concluded the district court erred in holding indefinite the claims reciting the terms “paresthesia-free,” “configured to,” and “means for generating.” The Federal Circuit also found the district court erred in its construction of the term “therapy signal,” though determined not indefinite by the district court. The Federal Circuit, therefore, vacated and remanded the district court’s judgment of invalidity of claims 7, 12, 35, 37 and 58 of the ’533 patent, claims 18, 34 and 55 of the ’125 patent, claims 5 and 34 of the ’357 patent and claims 1 and 22 of the ’842 patent.

Discussion

I. “paresthesia-free”

Several of Nevro’s asserted claims relate to methods and systems comprising a means for generating therapy signals that are “paresthesia-free.” Claim 18 of the ’125 patent and Claim 1 of the ’472 patent recite as follow:

18. A spinal cord modulation system for reducing or eliminating pain in a patient, the system comprising:

means for generating a paresthesia-free therapy signal with a signal frequency in a range from 1.5 kHz to 100 kHz; and

means for delivering the therapy signal to the patient’s spinal cord at a vertebral level of from T9 to T12, wherein the means for delivering the therapy signal is at least partially implantable.

1. A method for alleviating patient pain or discomfort, without relying on paresthesia or tingling to mask the patient’s sensation of the pain, comprising:

implanting a percutaneous lead in the patient’s epidural space, wherein the percutaneous lead includes at least one electrode, and wherein implanting the percutaneous lead includes positioning the at least one electrode proximate to a target location in the patient’s spinal cord region and outside the sacral region;

implanting a signal generator in the patient; electrically coupling the percutaneous lead to the signal generator; and

programming the signal generator to generate and deliver an electrical therapy signal to the spinal cord region, via the at least one electrode, wherein at least a portion of the electrical therapy signal is at a frequency in a frequency range of from about 2,500 Hz to about 100,000 Hz.

The district court presented its findings based on extrinsic evidence that “[a]lthough the parameters that would result in a signal that does not create paresthesia may vary between patients, a skilled artisan would be able to quickly determine whether a signal creates paresthesia for any given patient.” While holding that the term “paresthesia-free” does not render the method claims indefinite, the district court held indefiniteness regarding the asserted system and device claims. The Federal Circuit disagreed the indefiniteness holdings because the test of indefiniteness should be simply based on whether a claim “inform[s] those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention with reasonable certainty.” The Federal Circuit states that the district court applied the wrong legal standard and the test for indefiniteness is not whether infringement of the claim must be determined on a case-by-case basis.

The Federal Circuit states that “paresthesia-free,” a functional term defined by what it does rather than what it is, does not inherently render it indefinite. Furthermore, the Federal Circuit instructs that

i. functional language can “promote[] definiteness because it helps bound the scope of the claims by specifying the operations that the [claimed invention] must undertake.” Cox Commc’ns, 838 F.3d at 1232.

ii. the ambiguity inherent in functional terms may be resolved where the patent “provides a general guideline and examples sufficient to enable a person of ordinary skill in the art to determine the scope of the claims.” Enzo Biochem. Inc. v. Applera Corp., 599 F.3d 1325, 1335 (Fed. Cir. 2010).

II. “configured to”

Nevro’s asserted claim 1 of the ’842 patent relates to a spinal cord modulation system, which recites:

1. A spinal cord modulation system comprising:

a signal generator configured to generate a therapy signal having a frequency of 10 kHz, an amplitude up to 6 mA, and pluses having a pulse width between 30 microseconds and 35 microseconds; and

an implantable signal delivery device electrically coupleable to the signal generator and configured to be implanted within a patient’s epidural space to deliver the therapy signal from the signal generator the patient’s spinal cord.

The district court held indefiniteness because it determined that “configured to” is susceptible to meaning one of two constructions: “(1) the signal generator, as a matter of hardware and firmware, has the capacity to generate the described electrical signals (either without further programing or after further programming by the clinical programming software); or (2) the signal generator has been programmed by the clinical programmer to generate the described electrical signals.”

The Federal Circuit pointed out that “the test [of indefiniteness] is not merely whether a claim is susceptible to differing interpretations” because “such a test would render nearly every claim term indefinite so long as a party could manufacture a plausible construction.” Further, the Federal Circuit states that the test for indefiniteness is whether the claims, viewed in light of the specification and prosecution history, “inform those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention with reasonable certainty.” Nautilus, 572 U.S. at 910. (emphasis added).

The specifications of the asserted patents and prosecution history, indeed, help Nevro win the argument on “configured” means. Nevro’s asserted patents not only recites that “the system is configured and programmed to,” but also Nevro agreed with the examiner that “configured” means “programmed” as opposed to “programmable.” The limitation specifies the interpretation of the term “configured” and leads to this favorable decision towards Nevro. The “programmed” and “programmable” may sound similar. However, “programmable” would be appliable to a general machine, since any general signal generator would have the capacity to generate the described signals. The term “programmed” sets out its specific settings of the signal generator and limits such broad interpretation.

III. “means for generating”

Several asserted claims of the ‘125 patent recite “means for generating,” in which claim 18 recites as follow:

18. A spinal cord modulation system for reducing or eliminating pain in a patient, the system comprising:

means for generating a paresthesia-free therapy signal with a signal frequency in a range from 1.5 kHz to 100 kHz; and

means for delivering the therapy signal to the patient’s spinal cord at a vertebral level of from T9 to T12, wherein the means for delivering the therapy signal is at least partially implantable.

Nevro argued that the specification discloses a signal generator as the structure. The Federal Circuit agreed with Nevro and explained the difference comparing a general-purpose computer or processor. If the identified structure is a general-purpose computer or processor, it does require a specific algorithm. A signal or pulse generator is not considered as a general-purpose computer or processor, since it has the structure for the claimed “generating” function. Further, “the specification teaches how to configure the signal generators to generate and deliver the claimed signals using the recited parameters, clearly linking the structure to the recited function.” Hence, the Federal Circuit held that the district court erred in holding indefinite claims with the terms “means for generating.”

The terms such as “module” and “unit” are commonly used in many patent applications to convert method claims to system or device claims in electronic applications. However, without structural description in the specification, such claims are usually rejected due to indefiniteness. Hence, some may add some description related to general-purpose processors, integrated chips, or field-programmable gate arrays to define the “module” or “unit” and describe the functions.

IV. “therapy signal”

The Federal Circuit agreed that claims reciting a “therapy signal” are not indefinite, but held that the district court incorrectly construed the term. The Federal Circuit reiterated the context of the specification and prosecution history for understanding the words of a claim. It stated that “[t]he words of a claim are generally given their ordinary and customary meaning as understood by a person of ordinary skill in the art when read in the context of the specification and prosecution history.” Thorner v. Sony Comput. Entm’t Am. LLC, 669 F.3d 1362, 1365 (Fed. Cir. 2012).

Boston Scientific argued that the asserted claims reciting a “therapy signal” are indefinite because “two signals with the same set of characteristics (e.g., frequency, amplitude, and pulse width) may result in therapy in one patient and no therapy in another.” The Federal Circuit noted that “the fact that a signal does not provide pain relief in all circumstances does not render the claims indefinite.” Geneva, 349 F.3d at 1384.

Takeaway

- Functional language won’t be held indefinite simply for that reason or simply by interpreted in the claims.

- It is of importance to describe a related structure to support the functional terms in the specification, especially for applications having system or device claims converted from method claims.

- The test for indefiniteness is whether the claims, viewed in light of the specification and prosecution history, “inform those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention with reasonable certainty.” Nautilus, 572 U.S. at 910.

Tags: 35 U.S.C. § 112 > indefiniteness > Mean-Plus-Function > reasonable certainty

For Biotech, “Method of Preparation” Claims May Survive §101

| April 15, 2020

Illumina, Inc. v. Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc.

March 17, 2020

Lourie, Moore, and Reyna (Opinion by Lourie; Dissent by Reyna)

Summary

In a patent infringement litigation between the same parties that were involved in the earlier case, Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc. v. Sequenom, Inc., 788 F.3d 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (diagnostic patent deemed patent ineligible under 35 U.S.C. §101), the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (“Federal Circuit”) found the claimed “method of preparation” of a fraction of cell-free fetal DNA (“cff-DNA”) enriched in fetal DNA to be patent eligible, reversing the district court’s grant of summary judgment of patent ineligibility. A dissent by J. Reyna (author of the earlier Ariosa decision) asserts that there is nothing new and useful in the claims, other than the discovery that cff-DNA tends to be shorter than cell-free maternal DNA, and that use of known laboratory techniques and commercially available testing kits to isolate the naturally occurring shorter cff-DNA does not make the claims patent eligible.

Details

Illumina and Sequenom (collectively, “Illumina”) appealed a

summary judgment ruling of patent ineligibility by the United States District

Court for the Northern District of California.

The two patents at issue, USP 9,580,751 (the ‘751 patent) and USP

9,738,931 (the ‘931 patent), are unrelated to the diagnostic patent held

ineligible in the 2015 Ariosa decision. While the earlier litigated patent claimed a

method for detecting the small fraction of cff-DNA in the plasma and serum of a

pregnant woman that were previously discarded as medical waste, the present

‘751 and ‘931 patents claim methods for preparing a fraction of cff-DNA that is

enriched in fetal DNA. A problem with

maternal plasma is that it was difficult, if not impossible, to determine fetal

genetic markers (e.g., for certain diseases) because the proportion of circulatory

extracellular fetal DNA in maternal plasma was tiny as compared to the majority

of it (>90%) being circulatory extracellular maternal DNA. The inventor’s

“surprising” discovery was that the majority of circulatory extracellular fetal

DNA has a relatively small size of approximately 500 base pairs or less, as

compared to the larger circulatory extracellular maternal DNA. With this discovery, they developed the

following claimed methods for preparing a DNA fraction that separated fetal DNA

from maternal DNA from the maternal plasma and serum, to create a DNA fraction

enriched with fetal DNA.

‘931 Patent:

1. A method for preparing a deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) fraction from a pregnant human female useful for analyzing a genetic locus involved in a fetal chromosomal aberration, comprising:

(a) extracting DNA from a substantially cell-free sample of blood plasma or blood serum of a pregnant human female to obtain extracellular circulatory fetal and maternal DNA fragments;

(b) producing a fraction of the DNA extracted in (a) by:

(i) size discrimination of extracellular circulatory DNA fragments, and

(ii) selectively removing the DNA fragments greater than approximately 500 base pairs, wherein the DNA fraction after (b) comprises a plurality of genetic loci of the extracellular circulatory fetal and maternal DNA; and

(c) analyzing a genetic locus in the fraction of DNA produced in (b).

‘751 Patent:

1. A method, comprising:

(a) extracting DNA comprising maternal and fetal DNA fragments from a substantially cell-free sample of blood plasma or blood serum of a pregnant human female;

(b) producing a fraction of the DNA extracted in (a) by:

(i) size discrimination of extracellular circulatory fetal and maternal DNA fragments, and

(ii) selectively removing the DNA fragments greater than approximately 300 base pairs, wherein the DNA fraction after (b) comprises extracellular circulatory fetal and maternal DNA fragments of approximately 300 base pairs and less and a plurality of genetic loci of the extracellular circulatory fetal and maternal DNA fragments; and

(c) analyzing DNA fragments in the fraction of DNA produced in (b).

The Federal Circuit had consistently found diagnostic claims patent ineligible (as directed to natural phenomenon) (Athena Diagnostics, Inc. v. Mayo Collaborative Servs., LLC, 927 F.3d 1333 (Fed. Cir. 2019); Athena Diagnostics, Inc. v. Mayo Collaborative Servs., LLC, 915 F.3d 743 (Fed. Cir. 2019); Cleveland Clinic Found. v. True Health Diagnostics LLC, 859 F.3d 1352 (Fed. Cir. 2017)). In contrast, the Federal Circuit had also held that method of treatment claims are patent eligible (Endo Pharm. Inc. v. Teva Pharm. USA, Inc., 919 F.3d 1347 (Fed. Cir. 2019); Natural Alternative Int’l, Inc. v. Creative Compounds, LLC, 918 F.3d 1338 (Fed. Cir. 2019); and Vanda Pharm. Inc. v. West-Ward Pharm. Int’l Ltd., 887 F.3d 1117 (Fed. Cir. 2018)). However, this is not a diagnostic case, nor a method of treatment case. This is a method of preparation case – which the Federal Circuit found to be patent eligible.

The natural phenomenon at issue is that cell-free fetal DNA tends to be shorter than cell-free maternal DNA in the mother’s bloodstream. However, under the Alice/Mayo Step 1, the Federal Circuit held that these claims are not directed to a natural phenomenon. Instead, the claims are directed to a method that utilizes that phenomenon. The claimed method recites specific process steps – size discrimination and selective removal of DNA fragments above a specified size threshold. These process steps change the composition of the normal maternal plasma or serum, creating a fetal DNA enriched mixture having a higher percentage of cff-DNA fraction different from the naturally occurring fraction in the normal mother’s blood. “Thus, the process achieves more than simply observing that fetal DNA is shorter than maternal DNA or detecting the presence of that phenomenon.”

In distinguishing the earlier Ariosa case, the Federal Circuit stated, “the claims do not merely cover a method for detecting whether a cell-free DNA fragment is fetal or maternal based on its size.”

In distinguishing the Supreme Court decision in Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc., 569 U.S. 576 (2013), the Federal Circuit noted that the “Supreme Court in Myriad expressly declined to extend its holding to method claims reciting a process used to isolate DNA” and that “in Myriad, the claims were ineligible because they covered a gene rather than a process for isolating it.” Here, the method “claims do not cover cell-free fetal DNA itself but rather a process for selective removal of non-fetal DNA to enrich a mixture in fetal DNA.” This is the opposite of Myriad.

As for whether the techniques for size discrimination and selective removal of DNA fragments were well-known and conventional, those considerations are relevant to the Alice/Mayo Step 2 analysis, or to 102/103 issues – not for Alice/Mayo Step 1. The majority concluded patent eligibility under Step 1 and did not proceed to Step 2.

J. Reyna’s dissent focused on the claims being directed to a natural phenomenon because the “only claimed advance is the discovery of that natural phenomenon.” In particular, referring to a “string of cases reciting process claims” since 2016, the “directed to” inquiry under Alice/Mayo Step 1 asks “whether the ‘claimed advance’ of the patent ‘improves upon a technological process or is merely an ineligible concept.’” citing Athena, 915 F.3d at 750 and Genetic Techs., 818 F.3d at 1375. “Here, the claimed advance is merely the inventors’ ‘surprising[]’ discovery of a natural phenomenon – that cff-DNA tends to be shorter than cell-free maternal DNA in a mother’s bloodstream.” J. Reyna criticizes the majority for ignoring the “claimed advance” inquiry altogether.

Under the claimed advance inquiry, one looks to the written description. Here, the written description identifies the use of well-known and commercially available tools/kits to perform the claimed method. Checking for 300 and 500 base pairs using commercially available DNA size markers and kits does not constitute any “advance.” There is no improvement in the underlying DNA processing technology, but for checking the natural phenomenon of sizes indicative of cff-DNA.

J. Reyna also criticized the majority’s “change in the composition of the mixture” justification. “A process that merely changes the composition of a sample of naturally occurring substances, without altering the naturally occurring substances themselves, is not patent eligible.” Here, one begins and ends with the same naturally occurring substances – cell-free fetal DNA and cell free maternal DNA. There is no creation or alteration of any genetic information encoded in the cff-DNA. Therefore, the claims are directed to a natural phenomenon under Alice/Mayo Step 1.

J. Reyna also found no inventive concept under Alice/Mayo Step 2.

Take Away

- Until there is an en banc rehearing or a Supreme Court review of this case, this case is an example of a patent eligible method of preparation claim.

- For defendants, the “claimed advance” inquiry could help sink a claimed method under Alice/Mayo Step 1.

Tags: 101 > biotech > diagnostics > eligibility > Mayo/Alice Test > preparation > treatment

FACEBOOK’S IPRs CAN’T FRIEND EACH OTHER

| April 10, 2020

FACEBOOK, INC. v. WINDY CITY INNOVATIONS, LLC.

March 18, 2020

Prost, Plager and O’Malley (Opinion by Prost)

Summary: Plaintiff/Patent Holder Windy Citysuccessfully cross-appealed against Facebook on the issue of improper joinder of IPRs under 35 U.S.C. § 315(c). Facebook had filed IPRs within one year of Windy City’s District Court complaint and then joined later filed IPRs adding new claims. The PTAB had allowed the joinder. The CAFC vacated the Board’s joinder finding that Facebook could not join their own already filed IPRs.

Background:

In June 2016, exactly one year after being served with Windy City’s complaint for infringement of four patents related to methods for communicating over a computer-based net-work, Facebook timely petitioned for inter partes review (“IPR”) of several claims of each patent. At that time, Windy City had not yet identified the specific claims it was asserting in the district court proceeding. The four patents totaled 830 claims. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) instituted IPRs of each patent.

In January 2017, after Windy City had identified the claims it was asserting in the district court litigation, Facebook filed two additional petitions for IPR of additional claims of two of the patents. Facebook concurrently filed motions for joinder to the already instituted IPRs on those patents. By the time of filing the new IPRs, the one-year time bar of §315(b) had passed. The Board nonetheless instituted Facebook’s two new IPRs, and granted Facebook’s motions for joinder.

The Board agreed with Facebook that Windy City’s district court complaint generally asserting the “claims” of the asserted patents “cannot reasonably be considered an allegation that Petitioner infringes all 830 claims of the several patents asserted.” The Board therefore found that Facebook could not have reasonably determined which claims were asserted against it within the one-year time bar. Once Windy City identified the asserted claims after the one-year time bar, the Board found that Facebook did not delay in challenging the newly asserted claims by filing the second petitions with the motions for joinder.

The Board found that Facebook had shown by a preponderance of the evidence that some of the challenged claims are unpatentable, many of these claims had only been challenged in the later filed and joined IPRs. Facebook appealed and Windy City cross-appealed on the Board’s obviousness findings. Further, Windy City also challenged the Board’s joinder decisions allowing Facebook to join its new IPRs to its existing IPRs and to include new claims in the joined proceedings. Windy City’s cross-appeal on the joinder issue is addressed here.

Discussion:

In its cross-appeal, Windy City argued that the Board’s decisions granting joinder were improper on the basis that 35 U.S.C. § 315(c): (1) does not permit a person to be joined as a party to a proceeding in which it was already a party (“same-party” joinder); and (2) does not permit new issues to be added to an existing IPR through joinder (“new issue” joinder), including issues that would otherwise be time-barred.

Sections 315(b) and (c) recite:

(b) Patent Owner’s Action. —An inter partes review may not be instituted if the petition requesting the proceeding is filed more than 1 year after the date on which the petitioner, real party in interest, or privy of the petitioner is served with a complaint alleging infringement of the patent. The time limitation set forth in the preceding sentence shall not apply to a request for joinder under subsection (c).

(c) Joinder. —If the Director institutes an inter partes review, the Director, in his or her discretion, may join as a party to that inter partes review any person who properly files a petition under section 311 that the Director, after receiving a preliminary response under section 313 or the expiration of the time for filing such a response, determines warrants the institution of an inter partes review under section 314.

The CAFC noted that §315(b) articulates the time-bar for when an IPR “may not be instituted.” 35 U.S.C. §315(b). But §315(b) includes a specific exception to the time bar, namely “[t]he time limitation . . . shall not apply to a request for joinder under subsection (c).”

Regarding the propriety of Facebooks joinder, the Court held the plain language of §315(c) allows the Director “to join as a party [to an already instituted IPR] any person” who meets certain requirements. However, when the Board instituted Facebook’s later petitions and granted its joinder motions, the Board did not purport to be joining anyone as a party. Rather, the Board understood Facebook to be requesting that its later proceedings be joined to its earlier proceedings. The CAFC concluded that the Boards interpretation of §315(c) was incorrect because their decision authorized two proceedings to be joined, rather than joining a person as a party to an existing proceeding.

Section 315(c) authorizes the Director to “join as a party to [an IPR] any person who” meets certain requirements, i.e., who properly files a petition the Director finds warrants the institution of an IPR under § 314. No part of § 315(c) provides the Director or the Board with the authority to put two proceedings together. That is the subject of § 315(d), which provides for “consolidation,” among other options, when “[m]ultiple proceedings” involving the patent are before the PTO.35 U.S.C. § 315.

The Court went on to explain that the clear and unambiguous language of § 315(c) confirms that it does not allow an existing party to be joined as a new party, noting that subsection (c) allows the Director to “join as a party to [an IPR] any person who” meets certain threshold requirements. They noted that it would be an extraordinary usage of the term “join as a party” to refer to persons who were already a party. Finding the phrase “join as a party to a proceeding” on its face limits the range of “person[s]” covered to those who, in normal legal discourse, are capable of being joined as a party to a proceeding (a group further limited by the own-petition requirements), and an existing party to the proceeding is not so capable.

Regarding the second issue raised by Windy City that the Joinder cannot include newly raised issues, the CAFC found the language in §315(c) does no more than authorize the Director to join 1) a person 2) as a party, 3) to an already instituted IPR. Finding this language does not authorize the joined party to bring new issues from its new proceeding into the existing proceeding, particularly when those new issues are other-wise time-barred.

The Court noted that under the statute, the already-instituted IPR to which a person may join as a party is governed by its own petition and is confined to the claims and grounds challenged in that petition.

In reaching these conclusions, the Court did acknowledge the rock and hard place Facebook is left in.

We do not disagree with Facebook that the result in this particular case may seem in tension with one of the AIA’s objectives for IPRs “to provide ‘quick and cost effective alternatives’ to litigation in the courts.” [Citations omitted] Indeed, it is fair to assume that when Congress imposed the one-year time bar of § 315(b), it did not explicitly contemplate a situation where an accused infringer had not yet ascertained which specific claims were being asserted against it in a district court proceeding before the end of the one-year time period. We also recognize that our analysis here may lead defendants, in some circumstances, to expend effort and expense in challenging claims that may ultimately never be asserted against them.

However, the Court gave little remedy to bearing an enormous “effort and expense” of filing IPRs to 830 claims, asserting that they are bound by the unambiguous nature of the statute.

Petitioners who, like Facebook, are faced with an enormous number of asserted claims on the eve of the IPR filing deadline, are not without options. As a protective measure, filing petitions challenging hundreds of claims remains an available option for accused infringers who want to ensure that their IPRs will challenge each of the eventually asserted claims. An accused infringer is also not obligated to challenge every, or any, claim in an IPR. Accused infringers who are unable or unwilling to challenge every claim in petitions retain the ability to challenge the validity of the claims that are ultimately asserted in the district court. Accused infringers who wish to protect their option of proceeding with an IPR may, moreover, make different strategy choices in federal court so as to force an earlier narrowing or identification of asserted claims. Finally, no matter how valid, “policy considerations cannot create an ambiguity when the words on the page are clear.” SAS, 138 S. Ct. at 1358. That job is left to Congress and not to the courts.

Hence, the CAFC concluded that the clear and unambiguous language of §315(c) does not authorize same-party joinder, and also does not authorize joinder of new issues, including issues that would otherwise be time-barred. As a result, they vacated the Board’s decisions on all claims which were asserted in the later filed IPRs.

Take Away: A loop-hole between the one-year time bar, joinder statute for IPRs and District Court timing potentially gives a Plaintiff/Patent holder the ability to render an IPR more cost inefficient to a Defendant/Petitioner. By not identifying the claims to be asserted within one year of filing a patent infringement complaint, the patent holder can place a large burden on filing an IPR. Plaintiffs/Patent holders can strategize to assert infringement ambiguously to a prohibitive number of claims early in a District Court proceeding. Defendants will need to attempt to counter such a strategy by requesting District Courts to force Plaintiffs to identify the specific claims which will be asserted within one year of filing the complaint.

When the Broadest Reasonable Interpretation (BRI) Becomes Unreasonable

| March 26, 2020

Kaken Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Bausch Health Companies Inc. v. Andrei Iancu, Under Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property and Director of the United States Patent and Trademark Office

March 13, 2020

Before Newman, O’Malley, and Taranto (Opinion by Taranto)

U.S. patent practitioners constantly need to address use of the broadest reasonable interpretation (BRI) by Examiners during patent prosecution. During prosecution, arguments and amendments are typically presented to overcome prior art and become a part of the prosecution history along with the disclosure of the invention. This decision illustrates that definitions provided in the specification in conjunction with the prosecution history can potentially save a patent from a later challenge which invokes BRI. In this case, an erroneous claim construction of one claim limitation during an inter partes review caused the CAFC to reverse and remand back to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB).

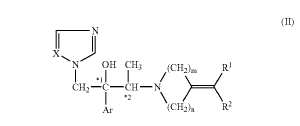

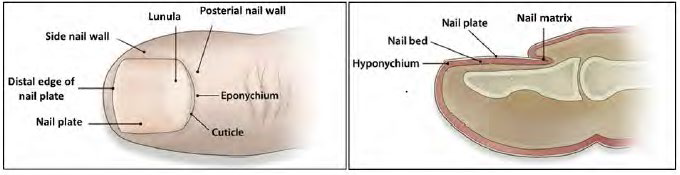

U.S. patent No. 7,214,506 is directed a method for treating onychomycosis. Claim 1 recites:

1. A method for treating a subject having onychomycosis wherein the method comprises topically administering to a nail of said subject having onychomycosis a therapeutically effective amount of an antifungal compound represented by the following formula:

wherein, Ar is a non-substituted phenyl group or a phenyl group substituted with 1 to 3 substituents selected from a halogen atom and trifluoromethyl group,

R1 and R2 are the same or different and are hydrogen atom, C1-6 alkyl group, a non-substituted aryl group, an aryl group substituted with 1 to 3 substituents selected from a halogen atom, trifluoromethyl group, nitro group and C1-16 alkyl group, C2-8 alkenyl group, C2-6 alkynyl group, or C7-12 aralkyl group,

m is 2 or 3,

n is 1 or 2,

X is nitrogen atom or CH, and

*1 and *2 mean an asymmetric carbon atom.

Acrux[1] had successfully obtained inter partes review of all claims of the ‘506 patent, with the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) ultimately determining that all claims are unpatentable for obviousness (based on a set of three references in combination with another set of two references for six total grounds). The first set of three references teach a method of topically treating onychomycosis with various azole compounds while the second set teaches KP-103 (an azole compound within the scope of claim 1) as an effective antifungal agent.

Kaken had argued that the phrase “treating a subject having onychomycosis” means “treating the infection at least where it primarily resides in the keratinized nail plate and underlying nail bed.” Kaken argued that the ‘506 patent’s key innovation is a topical treatment that can easily penetrate the tough keratin in the nail plate. This construction was rejected by the PTAB as too narrow because of the express definition of onychomycosis as including superficial mycosis, and the express definition in the specification of “nail includes the tissue or skin around the nail plate, nail bed, and nail matrix.” The PTAB concluded that “treating onychomycosis” includes treating “superficial mycosis that involves the skin or visible mucosa.”

The nail plate is defined as the “horny appendage of the skin that is composed mainly of keratin” whereas the “eponychium and hyponychium” are “the skin structures surrounding the nail.”

The CAFC reversed the PTAB’s claim construction as unreasonable in light of the specification and prosecution history as the broadest reasonable interpretation of treating a subject having onychomycosis “is penetrating the nail plate to treat a fungal infection inside the nail plate or in the nail bed under it.”

The CAFC came to this conclusion based on the specification’s characterization of onychomycosis in a way which links three other crucial passages. In particular, after defining the terms “skin” and “nail” and characterizing “superficial mycosis”, the specification stated that onychomycosis is “a kind of the above-mentioned superficial mycosis, in the other word a disease which is caused by invading and proliferating in the nail of human or an animal.” Thus, the specification conveys that onychomycosis is a disease with two basic features (1) of a disease of the nail and (2) it is a kind of superficial mycosis. As such, the BRI of onychomycosis would not include invasion of any part of what is defined as the nail other than the nail plate or nail bed, such as skin in its ordinary sense. The PTAB’s inclusion of the eponychium and hyponychium is unreasonable as the specification defined that onychomycosis is a disease involving invasion of the nail.

Other parts of the specification explain that an effective topical treatment would need to penetrate the nail plate, and the ‘506 patent explained that known topical treatments were largely ineffective. The patent further contains as objects as good permeability, good retention capacity and conservation of high activity to indicate that treating an infection of skin surrounding the nail plate alone would not require all these properties.

The prosecution history also included statements overcoming prior art as providing “decisive support” for Kaken’s claim construction. Kaken’s statements, followed by the examiner’s statements, make clear the limits on a reasonable understanding of what Kaken was claiming. The exchange between the examiner and Kaken:

“would leave a skilled artisan with no reasonable uncertainty about the scope of the claim language in the respect at issue here. Kaken is bound by its arguments made to convince the examiner that claims 1 and 2 are patentable. See Standard Oil, 774 F.2d at 452. Thus, Kaken’s unambiguous statement that onychomycosis affects the nail plate, and the examiner’s concomitant action based on this statement, make clear that “treating onychomycosis” requires penetrating the nail plate to treat an infection inside the nail plate or in the nail bed under it.”

Since the PTAB relied upon an erroneous claim construction throughout its consideration of facts in its obviousness analysis, the CAFC vacated the PTAB’s decision and remanded.

Takeaways:

Intrinsic evidence in the specification can overcome an ordinary meaning in the art (extrinsic evidence).

Although an applicant desires a broad interpretation of patent claims, too broad of an interpretation can open the patent to attacks. As such, the prosecution history plays an important role.

Some past decisions have taught patent

practitioners to avoid stating objects of the invention or discussion of prior

art. However, stating objects and providing a discussion of prior art can be

important for securing a proper claim construction, particularly in “crowded”

art areas.

[1] Acrux withdrew from the appeal, and the Director intervened to defend the PTAB’s decision.

Post-Importation Activity can be used by the International Trade Commission for determining a violation of Section 337

| March 18, 2020

Comcast Corporation v. ITC and Rovi Corporation

March 2, 2020

Newman, Reyna and Hughes. Opinion by Newman

Summary:

Rovi Corporation (hereinafter “Rovi”) filed a Section 337 complaint with the ITC for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 8,006,263 (“the ‘263 patent”) and U.S. Patent No. 8,578,413 (“the ‘413 patent”) based on importation of Comcast’s X1 set-top box used in an infringing system. Arris Enterprises and Technicolor SA imported the devices for Comcast and were also named in the complaint. The ITC found that even though infringement of the patents does not occur until after importation and when the customer connects a mobile device to the X1 set-top box, the X1 set-top boxes are still considered “articles that infringe” under Section 337. The ITC also found that Comcast induced the infringement by providing guidance and instructions to customers on how to operate the system. Comcast did not dispute direct infringement by the customer or its induced infringement. Comcast argued that the X1 set-top boxes are not “articles that infringe” under Section 337 because the boxes do not infringe at the time of importation. The CAFC agreed with the ITC affirming that the X1 set-top boxes are “articles that infringe” and that Comcast is considered an importer under Section 337.

Details:

The patents at issue are to an interactive television program guide system for remote access to television programs. The claims require a remote program guide access device such as a mobile device that is connected to an interactive television program guide system over a remote access link so that users can remotely access the program guide system. Claim 1 of the ‘263 patent is provided.

1. A system for selecting television programs over a remote access link comprising an Internet communications path for recording, comprising:

a local interactive television program guide equipment on which a local interactive television program guide is implemented, wherein the local interactive television program guide equipment includes user television equipment located within a user’s home and the local interactive television program guide generates a display of one or more program listings for display on a display device at the user’s home; and

a remote program guide access device located outside of the user’s home on which a remote access interactive television program guide is implemented, wherein the remote program guide access device is a mobile device, and wherein the remote access interactive television program guide:

generates a display of a plurality of program listings for display on the remote program guide access device, wherein the display of the plurality of program listings is generated based on a user profile stored at a location remote from the remote program guide access device;

receives a selection of a program listing of the plurality of program listings in the display, wherein the selection identifies a television program corresponding to the selected program listing for recording by the local interactive television program guide; and

transmits a communication identifying the television program corresponding to the selected program listing from the remote access interactive television program guide to the local interactive television program guide over the Internet communications path;

wherein the local interactive television program guide receives the communication and records the television program corresponding to the selected program listing responsive to the communication using the local interactive television program guide equipment.

The ITC found that the X1 set-top boxes are imported by Arris and Technicolor, and that Comcast is sufficiently involved with the design, manufacture and importation of the accused products such that Comcast is an importer under Section 337. The ITC further found that Comcast’s customers directly infringe the patents through use of the X1 systems in the US and that Comcast induced that infringement because Comcast instructs, directs, or advises its customers on how to carry out direct infringement of the claims of the patents.

Regarding Arris and Technicolor, the ITC found that they do not directly infringe the asserted claims of the patents because they do not provide a “remote access device,” and they do not contributorily infringe because the set-top boxes have substantial non-infringing uses.

The ITC issued a limited exclusion order excluding importation of the X1 set-top boxes by Comcast, including importation by Arris and Technicolor on behalf of Comcast. Comcast, Arris and Technicolor appealed the ITC decision.

Motion to Dismiss Appeal

The CAFC first addressed a motion to dismiss the appeal by Comcast, Arris and Technicolor because the patents at issue have now expired. The ‘263 patent expired on September 18, 2019 and the ‘413 patent expired on July 16, 2019. Comcast argued that the appeal is moot because after expiration of a patent, the ITC’s limited exclusionary order has no further prospective effect.

The ITC and Rovi opposed the motion to dismiss because there are continuing issues and actions to which these decisions are relevant, “whereby appellate finality is warranted because there are ongoing ‘collateral consequences.’” There are two other ITC investigations on unexpired Rovi patents that involve the X1 set-top boxes and that these investigations are likely to be affected by the decisions on this appeal as they have similar issues of importation.

The CAFC stated that “a case may remain alive based on collateral consequences, which may be found in the prospect that a judgment will affect future litigation or administrative action” citing Hyosung TNS Inc. v. U.S. Int’l Trade Comm’n, 926 F.3d 1353, 1358. The additional pending cases involve unexpired patents related to the same X1 set-top boxes and “the issues on appeal concern the scope of Section 337 as a matter of statutory interpretation. The CAFC denied the motion to dismiss because there are sufficient collateral consequences to negate mootness.

Articles that Infringe

Comcast did not dispute direct infringement by its customers, and did not dispute that it induces infringement by its customers. Comcast argued that its conduct is not actionable under Section 337 because Comcast’s conduct “takes place entirely domestically, well after, and unrelated to, the article’s importation.” Comcast stated that the imported X1 set-top boxes are not “articles that infringe” because the boxes do not infringe the patents at the time of importation.

The statutory basis for Section 337 investigations relevant to this case is in 19 U.S.C. § 1337(a) which states:

(1) Subject to paragraph (2), the following are unlawful . . . .

(B) The importation into the United States, the sale for importation, or the sale within the United States after importation by the owner, importer, or consignee, of articles that—

(i) infringe a valid and enforceable United States patent . . . .

Comcast argued that the ITC’s authority is limited to excluding articles that infringe “at the time of importation.” The ITC and Rovi, citing Suprema, Inc. v. U.S. Int’l Trade Comm’n, 796 F.3d 1338 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (en banc), stated that imported articles can infringe in terms of Section 337, when infringement occurs after importation. The basis of the Suprema decision was that the statute defines as unlawful “the sale within the United States after importation … of articles that—(i) infringe. The CAFC cited the following passage from the Suprema Decision:

The statute thus distinguishes the unfair trade act of importation from infringement by defining as unfair the importation of an article that will infringe, i.e., be sold, “after importation.” Section 337(a)(1)(B)’s “sale . . . after importation” language confirms that the Commission is permitted to focus on post-importation activity to identify the completion of infringement.

Suprema, Inc. at 1349.

Comcast argued that based on the facts in Suprema, inducement liability must be attached to the imported article at the time of the article’s importation. The imported X1 set-top boxes are incapable of infringement until the X1 set-top boxes are combined with Comcast’s domestic servers and its customers mobile devices. Comcast stated that any inducing conduct of articles that infringe occurs entirely after the boxes’ importation.

The CAFC stated that the ITC correctly held that Section 337 applies to articles that infringe after importation. The CAFC also cited the ITC decision which pointed out that Comcast designed the X1 set-top boxes to be used in an infringing manner, directed the manufacture overseas, and directed the importation. The ITC concluded that the inducing activity took place prior to importation, at importation, and after importation. The CAFC agreed with the ITC that X1 set-top boxes imported by and for Comcast for use by Comcast’s customers are “articles that infringe.”

Importer

Comcast argued that it is not an importer of the X1 set-top boxes because Arris or Technicolor are the actual importers, and because Comcast does not physically bring the boxes into the US and it does not exercise control over the importation process.

The CAFC agreed with the ITC that Comcast is an importer of the X1 set-top boxes under Section 337. The ITC found that Comcast is sufficiently involved in the importation of the X1 boxes that it satisfies the importation requirement. The ITC pointed out that the X1 boxes are particularly tailored for Comcast and they would not work with another cable operator’s system, Comcast is involved with the design, manufacture and importation of the X1 boxes, that Comcast controls the importation of the X1 boxes because Comcast provides Arris and Technicolor with technical documents so that the X1 boxes work as required by Comcast, and that the X1 boxes are designed only for Comcast. Comcast also restricts Arris from selling the products without Comcast’s permission. The ITC also found that Comcast directs Arris and Technicolor to deliver the accused products to Comcast delivery sites. The CAFC stated that the ITC’s findings are supported by substantial evidence.

Limited Exclusion Order

Arris and Technicolor argued that the limited exclusion order should not apply to them because they were found not to be infringers or contributory infringers. The ITC said that the exclusion order is within ITC’s discretion because the order is limited to importations “on behalf of Comcast” of articles whose intended use is to infringe the patents at issue. The CAFC agreed that the limited exclusion order is within the ITC’s discretion as “reasonably related to stopping the unlawful infringement.”

Comments

An importer of goods may not be able to avoid a Section 337 violation even though the goods do not infringe at the time of importation. Post-importation activity can be used to determine the completion of infringement. In this case, the X1 box itself does not infringe the patents at the time of importation. Customers infringe the patents only after a mobile device is connected to the system which is at the direction of Comcast.

Also, even if someone else imports the goods for you and you do not physically bring the goods into the US, you may still be considered an importer of the goods under Section 337 if you have a certain amount of control over the goods to be imported or the actual importation.

To Collect Damages for Patent Infringement, a Patentee Must Affirmatively Provide (1) Constructive Notice by Marking Products or b) Actual Notice to the Accused Infringer

| March 11, 2020

ARCTIC CAT, INC. v. BOMBARDIER RECREATIONAL, INC.

February 20, 2020

Lourie, Moore, and Stoll (Opinion by Lourie)

Summary

Arctic Cat sued Bombardier for patent infringement. Despite the court’s holding that Bombardier “willfully” infringed, Arctic Cat was unable to collect any damages for pre-trial sales, much less treble damages due to the courts holding that Arctic Cat did not provide proper notice as required under 35 U.S.C. 287, whether provided (a) constructively through proper patent marking or (b) actually through direct notice to Bombardier. The Federal Circuit also emphasized that the facts that Bombardier had actual knowledge of the patents and even willfully infringed were immaterial, and explained that affirmative notice by the patentee is statutorily required.

Background

a. Factual Setting

Arctic Cat, Inc. (Arctic Cat) sued Bombardier Recreational Products, Inc. (Bombardier) for infringement of U.S. Patent Nos. 6,793,545 and 6,568,969 related to steering systems for personal watercraft.

Artic Cat only sold product via its licensee, Honda. According to the terms of the licensee agreement, Honda was expressly not required to provide patent marking to provide constructive notice of the ‘545 or ‘969 patents to which the licensed products applied.

b. Procedural Background

Arctic Cat initially sued Bombardier in the Southern District of Florida for infringement of the ‘545 and ‘969 patents. The district court held that Bombardier willfully infringed. Additionally, the district court also held that Bombardier failed to meet its burden to prove that unmarked products sold by Honda practiced the claimed invention.

Bombardier previously appealed to the Federal Circuit, and the Federal Circuit previously affirmed the district courts holding of willful infringement. However, the Federal Circuit previously remanded the case back to the district court on the issue of patent marking, explaining that the burden was on the patentee to prove that the identified products do not practice the claimed invention once the alleged infringer identifies a product alleged to practice the claimed invention.

On remand, the district court held that Arctic Cat was unable to recover any pre-complaint damages for failure to provide constructive or actual notice to Bombardier.

The Federal Circuit’s Decision

Patent Marking Statute

In the opinion, the Federal Circuit explains that “[i]n this appeal, we are tasked with interpreting the marking statute, 35 U.S.C. § 287. Statutory interpretation is a question of law that we review de novo.”

Under 35 U.S.C. 287, “patentees, and persons making, offering for sale, or selling within the United States any patented article for or under them, or importing any patented article into the United States, may give notice to the public that the same is patented … by fixing thereon the word “patent” … . In the event of failure so to mark, no damages shall be recovered by the patentee in any action for infringement, except on proof that the infringer was notified of the infringement and continued to infringe thereafter, in which event damages may be recovered only for infringement occurring after such notice. Filing of an action for infringement shall constitute such notice.”

Requirements under the Patent Marking Statute

The Federal Circuit explains that under 35 U.S.C. 287, “a patentee who makes or sells patented articles can satisfy the notice requirement of § 287 either by providing constructive notice—i.e., marking its products—or by providing actual notice to an alleged infringer,” and explains that “[a]ctual notice requires the affirmative communication of a specific charge of infringement by a specific accused product or device.”

Constructive Notice

With respect to the requirement of “constructive notice,” Arctic Cat argued that such notice wasn’t required because after initially selling unmarked products, Honda ceased sales. As a result, Arctic Cat asserts that such cessation of sales excuses non-compliance with the notice requirement in a similar manner to how a patentee that does not make any sales is not required to provide such notice. However, the Federal Circuit explained that after an unmarked product is sold into the market, such products “remain on the market, incorrectly indicating to the public that there is no patent,” and held that “once a patentee begins making or selling a patented article, the notice requirement attaches, and the obligation imposed by 35 U.S.C. 287 attaches and is discharged only by providing actual or constructive notice.”

Actual Notice

With respect to the requirement of “actual notice,” Arctic Cat argued that the defendant had actual knowledge of the patent and, thus, had actual notice of the patent. Moreover, Arctic Cat argued that such actual knowledge was also evidenced by the district court’s holding of “willful” infringement. However, the court explained that “whether a patentee provided actual notice must focus on the action of the patentee, not the knowledge or understanding of the infringer, and that it is irrelevant whether the defendant knew of the patent or [even] knew of his own infringement.”

Licensees

With respect to sales through licensees, the Federal Circuit explained that “[a] patentee’s licensees must also comply with § 287.” While licensees have such an obligation, the court further explained that “courts may consider whether the patentee made reasonable efforts to ensure third parties’ compliance with the marking statute.” However, the court noted that in this case Arctic Cat’s “license agreement with Honda expressly states that Honda had no obligation to mark.”

Takeaways

- With respect to “constructive notice,” an important take away is to remember that constructive notice can be provided at any time by starting proper patent marking. Thus, in the event that a patentee initially does not provide proper patent marking, proper patent marking can be correctively initiated at a later date.

- With respect to “actual notice,” an important take away is to remember that an alleged infringer’s “actual knowledge” of the patent (and even “intentional” or “willful” infringement of that patent) is irrelevant to the notice requirement under 35 U.S.C. 287, which is entirely dependent on the actions of the patentee.

a. For example, if an infringer is aware that the patentee’s product is not marked, the infringer could potentially continue infringement without concern of potential damages until receipt of actual notice from the patentee.

- With respect to sales of patented products through licensees or third parties, an important take away is to remember that such licensees or third parties “must also comply” with 35 U.S.C. 287. However, the court indicates that “a court may consider whether the patentee made reasonable efforts to ensure third parties compliance with the marking statute.” Accordingly, another important takeaway is to ensure that licensing agreements include reasonable requirements for marking by the licensee.

- With respect to the requirement of patent marking, the opinion also provides some other helpful reminders that:

a. The patent marking requirement does not apply in the context of “process” or “method” claims. Notably, this provides another reason to consider inclusion of “method” or “process” claims.

b. The patent marking requirement also does not apply in the event that a patentee never makes or sells a product. Notably, this provides some advantage to non-practicing entities (NPEs).

Should’ve, Could’ve, Would’ve; Hindsight is as common as CDMA, allegedly!

| March 5, 2020

Acoustic Technology, Inc., vs., Itron Networked Solutions, In.

February 13, 2020

Circuit Judges Moore, Reyna (author) and Taranto.

Summary:

i. Background:

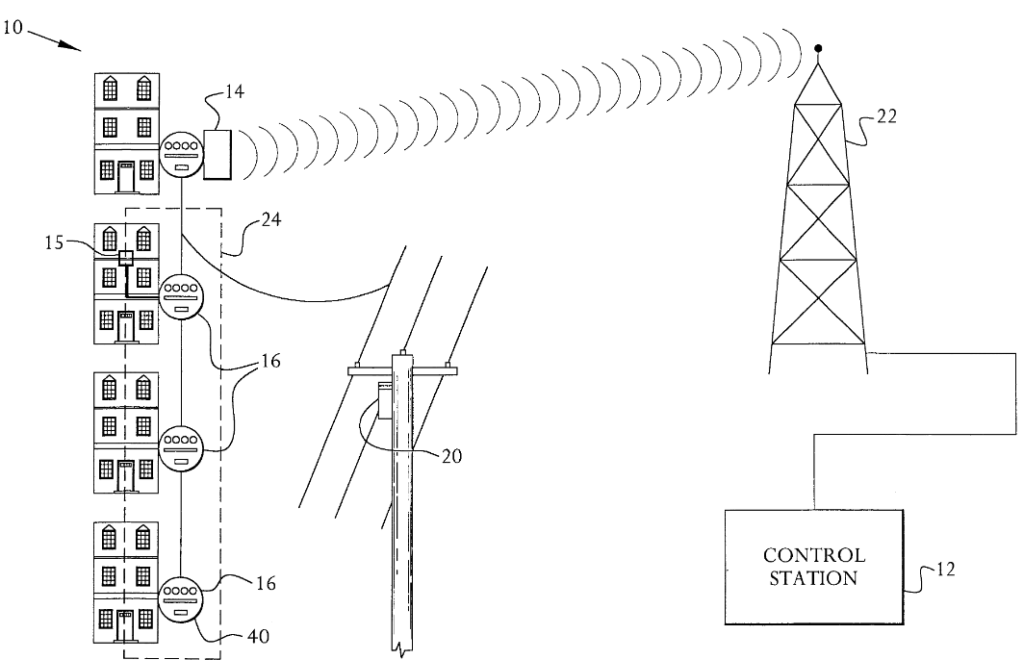

Acoustic owns U.S. Patent No., 6,509,841 (‘841 hereon), which relates to communications systems for utility providers to remotely monitor groups of electricity meters.

Back in 2010, Acoustic sued Itron for infringement of the ‘841 patent, with the parties later settling. As part of this settlement, Acoustic licensed the patent to Itron. As a result of the lawsuit, Itron was time-barrred from seeking inter partes review (IPR), of the patent. See 35 U.S.C. § 315(b).

Six years later, Acoustic sued Silver Spring Networks, Inc., (SS) for infringement, and in response, SS filed an IPR petition that has given rise to this Appeal.

Prior to and thereafter filing the IPR, SS was in discussions with Itron regarding a potential merger. Nine days after the Board instituted IPR, the parties agreed to merge. It was publicly announced the following day. The merger was completed while the IPR proceeding remained underway. SS filed the necessary notices that listed Itron as a real-party-in-interest.

Finally, seven months after Itron and SS completed the merger, the Board entered a final written decision wherein they found claim 8 of the ‘841 patent unpatentable. Acoustic did not raise a time-bar challenge to the Board.

ii. Appeal Issues:

ii-a: Acoustic alleges the Boards final written decision should be vacated because the underlying IPR proceeding is time-barred under 35 U.S.C. § 315(b).

ii.b: Acoustic alleges the Boards unpatentability findings are unsupported.

iii. IPR

35 U.S.C. § 315(b)

An inter partes review may not be instituted if the petition requesting the proceeding is filed more than 1 year after the date on which the petitioner, real party in interest, or privy of the petitioner is served with a complaint alleging infringement of the patent.