Same difference: A broad interpretation of “contrast” renders patented design obvious in view of prior art showing a similar “level of contrast”.

| October 19, 2020

Sealy Technology, LLC v. SSB Manufacturing Company (non-precedential)

August 26, 2020

Before Prost, Reyna, and Hughes (Opinion by Prost).

Summary

In nixing a design patent purporting to show “contrast” between design elements, the Federal Circuit broadly interprets “contrast” in the claimed design as not requiring a level of contrast that is different than what is available in the prior art.

Details

In their briefs to the Federal Circuit, Sealy Technology, LLC (“Sealy”) told the story about how, during a slump in sales around 2009, they re-designed their Stearns & Foster luxury-brand mattresses to visually distinguish their mattresses in a marketplace overrun with white or otherwise monochromatic mattress designs.

To be visually distinct, Sealy incorporated a “bold” combination of contrast edging running horizontally along the edges of the mattress and around the handles on the mattress.

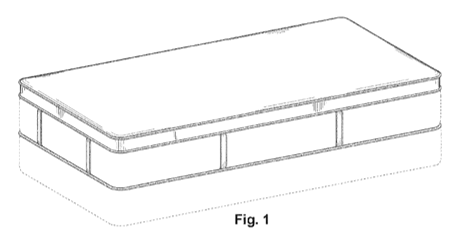

Sealy claimed this design in their U.S. Design Patent No. 622,531 (“D531 patent”). The D531 patent claimed “[t]he ornamental design for a Euro-top mattress design, as shown and described”, with Figure 1 being representative:

The D531 patent did not contain any textual descriptions of the contrast edging in Sealy’s mattress design.

Sealy’s dispute with Simmons Bedding Company (“Simmons”) began shortly after the D531 patent issued, when in 2010, Sealy sued Simmons for infringing the D531 patent. The product at issue was Simmons’s Beautyrest-brand mattress:

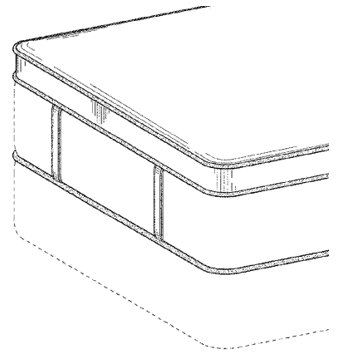

in 2011, Simmons sought an inter partes reexamination of the D531 patent. During the first round of the reexamination, the Examiner interpreted the claimed design as including the following elements:

- The horizontal piping along the edges of the top and bottom of the mattress and along the top flat surface of the pillow top layer has a contrasting appearance.

- The [eight] flat vertical handles each have contrasting sides of edges running vertically with the length of the handles.

However, the Examiner declined to adopt any of Simmons’s requested anticipation and obviousness challenges. And when Simmons appealed the Examiner’s refusal to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, Sealy vouched for the Examiner’s interpretation.

Unfortunately for Sealy, the Board on appeal entered new obviousness rejections. A second round of the reexamination followed. This time around, the Examiner adopted the Board’s rejections, which Sealy was unable to overcome even after a second appeal to the Board. Sealy then appealed the rejections to the Federal Circuit.

Sealy raised two main issues on appeal: first, whether the Board correctly construed the “contrast” in the claimed design; and second, whether the cited prior art was a proper primary reference.

On the question of claim construction, the Board had determined that “the only contrast necessary is one of differing appearance from the rest of the mattress”, whether by contrasting fabric, contrasting color, contrasting pattern, and contrasting texture.

Sealy argued that the Board’s construction was too broad. The proper construction, argued Sealy, should require a more specific level of contrast, that is, “a contrasting value and/or color” or “something that causes the edge to stand out or to be strikingly different and distinct from the rest of the design”.

Sealy relied on MPEP 1503.02(II), which provides that “contrast in materials may be shown by using line shading in one area and stippling in another”, that “the claim will broadly cover contrasting surfaces unlimited by color”, and that “the claim would not be limited to specific material”. Sealy also argued that a designer of ordinary skill in the art would have understood the D531 patent as requiring a more specific degree of contrast than the Board’s construction.

The Federal Circuit disagreed.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the Examiner and the Board’s findings that the patent contained no textual descriptions about contrast in the claimed design, that the drawings did not convey a different level of contrast than the prior art, and that Sealy’s argument regarding the understanding of a designer skilled in the art lacked evidentiary support..

On the question of obviousness, Sealy challenged the Board’s reliance on the Aireloom Heritage mattress shown below, arguing that the prior art mattress lacked the requisite contrast.

The weakness in Sealy’s argument was that its success depended entirely on the Federal Circuit adopting Sealy’s claim construction. And because the Federal Circuit did not find that the claimed design required a “strikingly different” contrast between the edging and the rest of the mattress, the Federal Circuit agreed with the Board’s determination that the prior art mattress had “at least some difference in appearance” between the edging and the rest of the mattress. This was sufficient to qualify the Aireloom Heritage mattress as a proper primary reference.

Takeaway

- Consider adding strategic textual descriptions in the specification to clarify the claimed design. For example, in Sealy’s case, since the contrast in the claimed design is provided in part by contrast in color, it may have been helpful to include such descriptions as “Figure 1 is a perspective view of a mattress showing a first embodiment f the Euro-top mattress design with portions shown in stippling to indicate color contrast”.

- If color contrast is important to the claimed design, consider adding solid black shading to the appropriate portions. 37 C.F.R. 1.152 (“Solid black surface shading is not permitted except when used to represent the color black as well as color contrast”).

- If the color scheme is important to the claimed design, consider filing a color drawing with the design application. One of Apple’s design patents on the iPhone graphical user interface includes a color drawing, which helped Apple’s infringement case against Samsung because similarities between the claimed design and the graphical user interface on Samsung’s Galaxy phones were immediately noticeable.

LICENSING AGREEMENTS AND TESTIMONIES COULD BE USED AS EVIDENCE OF SECONDARY CONSIDERATIONS TO OVERCOME OBVIOUSNESS ONLY WHEN THEY PROVIDE A “NEXUS” TO THE PATENTS

| October 10, 2020

Siemens Mobility, Inc. v. U.S. PTO

September 8, 2020

Lourie (author), Moore, and O’Malley

Summary:

The Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s final decision that claims of Siemens’s patents are unpatentable as obvious. The Federal Circuit found that the PTAB’s findings in claim construction of “corresponding regulations,” and evaluation of Siemens’s evidence of secondary considerations are clearly supported by substantial evidence.

Details:

Siemens Mobility, Inc. (“Siemens”) appeals from two final decisions of the PTAB, where the PTAB held that claims 1-9 and 11-19 of U.S. Patent No. 6,609,049 (“the ‘049 patent) and claims 1-9 and 11-19 of U.S. Patent No. 6,824,110 (“the ‘110 patent) were unpatentable.

The ‘049 patent and ‘110 patent

Siemens’s ‘049 and ‘110 patents are directed to methods and systems for automatically activating a train warning device, including a horn, at various locations. The systems include a control unit, a GPS receiver, and database of locations of grade crossings, and a horn. Siemens’s two patent disclose that if that grade crossing is subject to state regulations, the horn is activated based on those state regulations. If that grade crossing is not subject to state regulations, Siemens’s system considers that crossing as subject to a Federal Railroad Administration regulation and sounds the horn when the train is 24 seconds or fewer away from the crossing.

Independent claim 1 of ‘110 patent:

1. A computerized method for activating a warning device on a train at a location comprising the steps of:

maintaining a database of locations at which the warning device must be activated

and corresponding regulations concerning activation of the warning device;

obtaining a position of the train from a positioning system;

selecting a next upcoming location from among the locations in the database based at least in part on the position;

determining a point at which to activate the warning device in compliance with a

regulation corresponding to the next upcoming location; and

activating the warning device at the point.

The claims of the ‘049 and ‘110 patents substantially similar.

PTAB

Westinghouse Air Brake Technologies Corporation (“Westinghouse”) petitioned for IPR, challenging claims of both ‘049 and ‘110 patents under §103.

The PTAB found that all challenged claims would have been obvious over two references (Byers and Michalek). In addition, the PTAB did not found Siemens’s evidence of secondary considerations to be persuasive. Finally, the PTAB found that a skilled artisan would have combined the teachings of both references.

Siemens appealed.

CAFC

Three aspects of the PTAB decisions at issue in the appeal:

- The board’s claim construction of “corresponding regulations”;

- The board’s evaluation of Siemens’s evidence of secondary considerations; and

- The board’s findings of a person of skill in the art would have combined both references.

As for the second issue, Siemens presented two license agreements to both patents. Also, Siemens provided evidence regarding Westinghouse’s request to license and testimony from Westinghouse employees regarding the strength of two patents.

Siemens argued that the PTAB improperly discounted this evidence for lack of nexus.

The CAFC did not find those license agreements to be persuasive.

The CAFC noted that the license agreement with Norfolk Southern was presented to the PTAB with royalty information redacted and that another license was provided only for a nominal fee. Also, the CAFC noted that a license request from Westinghouse was for avoiding the cost of a pending patent infringement suit.

Furthermore, the CAFC agreed with the PTAB’s position that testimony from Westinghouse “provided a scant basis for accessing the value of the ‘110 patent” because while the testimony referred to a “horn sequencing patent” or “automatic horn activation,” it did not provide any connection to the language of the claims.

Therefore, the CAFC held that the PTAB’s findings were clearly supported by substantial evidence.

Takeaway:

- In the obviousness analysis, a nexus is required between the merits of the claimed invention and the offered evidence.

- Licensing agreements and testimonies could be used as evidence of secondary considerations to overcome obviousness only when they provide a “nexus” to the patents at issue.

Tags: employee testimony > evidence of secondary considerations > licensing agreement > nexus > obviousness

Prosecution history estoppel applies to narrowing amendment for a purpose, but not for all purposes

| September 25, 2020

Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Et Al. v. 10X Genomics Inc.

August 3, 2020

Newman, O’Malley (Opinion author), and Taranto

Summary

The Federal Circuit held that 10X infringes Bio-Rad’s ‘083 patent under the doctrine of equivalents because a tangential exception to the prosecution history estoppel applies in this case.

Details

Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. and the University of Chicago (collectively, “Bio-Rad”) accused 10X Genomics Inc. (“10X”) of infringing three patents: U.S. Patent Nos. 8,888,083 (“083 patent”); 8,304,193 (“193 patent”); and 8,329,407 (“407 patent”). The United States District Court for the District of Delaware held that 10X willfully infringed all three patents and awarded damages in an amount of $23,930,716.

The patents-in-suit are directed to systems and methods for forming microscopic droplets (also called “plugs”) of fluids to perform biochemical reactions. Claim 1 of the ‘083 patent, as below, is representative:

A microfluidic system comprising:

a non-fluorinated microchannel;

a carrier fluid comprising a fluorinated oil and a fluorinated surfactant comprising a hydrophilic head group in the microchannel;

at least one plug comprising an aqueous plug-fluid in the microchannel and substantially encased by the carrier-fluid, wherein the fluorinated surfactant is present at a concentration such that surface tension at the plug-fluid/microchannel wall interface is higher than surface tension at the plug-fluid/carrier fluid interface.

During prosecution, the inventors amended the claims, as underlined above, to distinguish from a prior art, U.S. Patent No. 7,294,503 (“Quake”). Quake disclosed microchannels formed or coated with Teflon (a fluorinated polymer) or other fluorinated oils. Furthermore, the inventors argued that their invention attempts to prevent droplets from sticking to the walls of microchannels and requires that the “surfactant should be chemically similar to the carrier fluid and chemically different from the channel walls.” That is, the non-fluorinated microchannels and the fluorinated surfactant are required not to react with each other. This is the purpose of the amendment. In contrast, Quake did not teach that microchannels and carriers fluids were chemically distinct, and the fluorinated microchannels and surfactants could, therefore, react with each other.

After the litigation was filed, 10X modified its products to add 0.02% Kynar-a non-reactive amount of a fluorine-containing resin-to its microchannels. 10X concedes that the addition of this amount of Kynar is irrelevant to the functioning of its products. In the District Court, the jury found that 10X’s accused products, as modified, do not literally satisfy the “non-fluorinated microchannels” limitation, but meet the limitation under the doctrine of equivalents. On appeal, among other issues, 10X argued that prosecution history estoppel and claim vitiation barred Bio-Rad’s theory of equivalence. The District Court held that prosecution history estoppel does not apply in this case because the amendment at issue was only tangentially related to the accused equivalent.

On appeal, 10X continued to argue that prosecution history estoppel applies because the inventors’ amendment narrowed the claims to recite a “non-fluorinated microchannel” to overcome Quake, which taught “fluorinated” microchannels. As such, the inventors surrendered the right to expand their monopoly to cover microchannels containing fluorine, “for whatever purpose.” In response, Bio-Rad counter argued that the reason for narrowing the claims was peripheral, or not directly relevant to the alleged equivalent. Bio-Rad contends that the patentees amended the claims to make clear that the carrier fluid and the microchannel wall should be chemically distinct, which bears no more than a tangential relation to the alleged equivalent-microchannel walls containing a nominal amount of fluorine that is not chemically distinct from the carrier fluid. The Federal Circuit agreed with Bio-Rad, and reasoned that inventors surrendered microchannels coated with fluorine that reacted with carrier fluids, not those containing de minimis amounts of fluorine that have no effect on how the microchannel functions in the system. The narrowing amendment can only be said to have a tangential relation to the equivalent at issue-negligibly fluorinated microchannels, or microchannels with non-fluorinated properties. That is, the inventors surrendered microchannels coated with fluorine for a purpose, but not for all purposes.

Take away

- During prosecution, inventors should also explain in detail the purpose of the amendment of claims in order to narrow the scope surrendered by the amendment.

Tags: doctrine of equivalents > prosecution history estoppel > tangential exception

Be careful in translating foreign applications into English, particularly with respect to uncommon terms

| September 18, 2020

IBSA Institut Biochimique, S.A., Altergon, S.A., IBSA Pharma Inc. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc.

July 31, 2020

Prost (Chief Judge), Reyna, and Hughes. Opinion by Prost.

Summary

In a U.S. application claiming priority to an Italian application, the term “semiliquido” was translated as “half-liquid.” This term was found to be indefinite, in view of a lack of a clear meaning in the art, as well as the statements of the prosecution history and specification. Further, attempts to argue that the term “half-liquid” should be interpreted as “semi-liquid” failed due to inconsistencies with the specification.

Details

IBSA is the owner of U.S. Patent No. 7,723,390, which claims priority to an Italian application. Claim 1 of the ‘390 patent is as follows:

1. A pharmaceutical composition comprising thyroid hormones or their sodium salts in the form of either:

a) a soft elastic capsule consisting of a shell of gelatin material containing a liquid or half-liquid inner phase comprising said thyroid hormones or their salts in a range between 0.001 and 1% by weight of said inner phase, dissolved in gelatin and/or glycerol, and optionally ethanol, said liquid or half-liquid inner phase being in direct contact with said shell without any interposed layers, or

b) a swallowable uniform soft-gel matrix comprising glycerol and said thyroid hormones or their salts in a range between 0.001 and 1% by weight of said matrix.

Teva filed an ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification asserting that the patent is invalid. In particular, Teva asserted that claim 1 is invalid as being indefinite. Upon filing of the ANDA, IBSA filed suit against Teva.

The key issue in this case is the meaning of the term “half-liquid.” IBSA asserted that this term should mean “semi-liquid, i.e., having a thick consistency between solid and liquid.” Meanwhile, Teva argued that the term is either invalid, or should be interpreted as a “non-solid, non-paste, non-gel, non-slurry, non-gas substance.”

District Court

At the district court, all parties agreed that the intrinsic record does not define the term “half-liquid.” However, IBSA asserted that its construction is supported by intrinsic evidence, including the Italian priority application. The Italian priority application used the term “semiliquido” at all places where the ‘390 patent used the term “half-liquid.” In 2019, IBSA obtained a certified translation in which “semiliquido” was translated as “semi-liquid.” IBSA asserted that “semi-liquid” and “half-liquid” would be understood as synonyms.

However, the district court noted that there were other differences between the Italian priority application and the ‘390 patent specification, beyond the “semiliquido”/“half-liquid” difference. These differences included the “Field of Invention” and “Prior Art” sections. Because of these other differences, the district court concluded that the terminology in the U.S. specification reflected the Applicant’s intent, and that any difference was deliberate.

Furthermore, the district court noted that during prosecution, there was at one point a dependent claim using the term “semi-liquid” which was dependent on an independent claim using the term “half-liquid.” Even though the term “semi-liquid” was eventually deleted, this was interpreted as evidence that the terms are not synonymous.

Additionally, the specification cited to pharmaceutical references that used the term “semi-liquid.” According to the district court, this shows that the Applicant knew of the term “semi-liquid,” but chose to use the term “half-liquid” instead.

Finally, all extrinsic evidence was considered by the district court to be unpersuasive. The extrinsic evidence used the term “half-liquid” in a different context than the present application. As such, the district court concluded that the term “half-liquid” was “exceedingly unlikely” to be a term of art at the time of filing.

Next, the district court analyzed whether a skilled artisan would nevertheless be able to determine the meaning of the term “half-liquid.” First, the court noted that the claims do not clarify what qualifies as a half liquid, other than the fact that it is neither liquid nor solid. The district court concluded that one skilled in the art would only understand “half-liquid” to be something that is not a gel or paste. This conclusion was based on a passage in the specification that stated:

In particular, said soft capsule contains an inner phase consisting of a liquid, half-liquid, a paste, a gel, an emulsion, or a suspension comprising the liquid (or half-liquid) vehicle and the thyroid hormones together with possible excipients in suspension or solution.

Additionally, during prosecution, the Applicant responded to an obviousness rejection by including the statement that the claimed invention “is not a macromolecular gel-lattice matrix” or a “high concentration slurry.” As such, the Applicant disclaimed these from the scope of “half-liquid.”

Finally, the district court commented on the expert testimony. IBSA’s expert had “difficulty articulating the boundaries of ‘half-liquid’” during his deposition. Meanwhile, Teva’s expert stated that “half-liquid is not a well-known term in the art.”

Based on the above, the district court concluded that one having ordinary skill in the art would find it impossible to know “whether they are dealing with a half-liquid within the meaning of the claim,” and concluded that the claims are invalid as being indefinite.

CAFC

The CAFC agreed with the district court on all points. First, the CAFC agreed that the claim language does not clarify the issue. Rather, the claim language only clarifies that “half-liquid” is not the same as liquid.

As to the specification, the CAFC agreed with the district court that the portion of the specification noted above clarifies that “half-liquid” cannot mean a gel or paste. Moreover, the CAFC cited another passage, which refers to “soft capsules (SEC) with liquid, half-liquid, paste-like or gel-like inner phase.” The CAFC concluded that the use of the word “or” in these passages shows that “half-liquid” is an alternative to the other members of the list, such as pastes and gels. Meanwhile, since gels and pastes have a thick consistency, IBSA’s proposed claim construction is in contradiction with these passages of the specification.

Additionally, the CAFC refuted IBSA’s argument that the specification includes passages that are at odds with the description of “half-liquid” as an alternative to pastes and gels. These passages include:

…an SEC capsule containing an inner phase consisting of a paste or gel comprising gelatin and thyroid hormones or pharmaceutically acceptable salts thereof…in a liquid or half liquid.

However, this argument conflates the inner phase and the vehicle within the inner phase, and does not explain why these are the same.

Additionally, the CAFC noted that the specification includes a list of examples of liquid or half-liquid vehicles, and a reference to a primer on making “semi-liquids.” However, even if some portions of the specification could support the position that “half-liquid” and “semi-liquid” are synonyms, the specification fails to describe the boundaries of “half-liquid.”

Next, the CAFC discussed the prosecution history. As in the district court, IBSA asserted that “half-liquid” means “semi-liquid.” This was because the term “half-liquid” was used in all places where “semiliquido” was used, and a certified translation showed that “semiliquido” is translated as “semi-liquid.”

The CAFC agreed the use of “half-liquid” was intentional, relying on not only the differences between the Italian application and the U.S. application noted by the district court, but others as well. In particular, claim 1 of the U.S. application differed from claim 1 of the Italian application, and incorporated an embodiment not found in the Italian application. Further, the Italian application does not use the term “gel” in the first passage noted above.

The CAFC also agreed with the district court that the temporary presence of a claim reciting “semi-liquid” dependent on a claim reciting “half-liquid” further demonstrates that these terms are not synonymous.

Finally, the CAFC reviewed the extrinsic evidence. The CAFC noted the IBSA’s expert’s inability to explain the boundaries of the term “half-liquid.” The CAFC also pointed out that only one dictionary of record had a definition including the term “half liquid,” and this was a non-scientific dictionary. This dictionary defined “semi-liquid” as “Half liquid; semifluid.” But, IBSA’s expert stated that “semifluid” and “half-liquid” are not necessarily the same.

Further, although other patents using the term “half-liquid” were cited, these patents used the term in a different context, and thus were not helpful to define the term in the context of the ‘390 patent. IBSA’s expert acknowledged the lack of any other literature such a textbook or a peer-reviewed journal using the term “half-liquid.” Additionally, IBSA’s expert stated that he was uncertain about whether his construction of “half-liquid” would exclude gels or slurries.

Based on the above, the CAFC concluded that the term “half-liquid” does not have a definite meaning. As such, the claim is invalid as failing to comply with §112.

Takeaways

-When translating a specification from a foreign language to English, it is preferable that the specifications are as close to identical as possible.

-If there are differences between a foreign language specification and the U.S. specification, these differences should ideally be limited to non-technical portions of the specification.

-If using a term that is not widely used, it is recommended to clearly define this term in the record. Failure to do so may result in the term being interpreted in an unintended manner, or worse, the term being considered indefinite.

-Where there are discrepancies between a foreign priority application and a US application, such differences may be interpreted as intentional.

In a patent infringement action involving standard essential patents, standard-essentiality is to be determined by judges in bench trials and juries in jury trials

| September 11, 2020

Godo Kaisha IP Bridge 1 v. TCL Communication Technology Holdings Ltd. (Fed. Cir. 2020) (Case No. 2019-2215)

August 4, 2020

Prost (Chief Judge), Newman and O’Malley. Court opinion by O’Malley

Summary

The Federal Circuit unanimously affirmed all aspects of the district court’s rulings and the verdict predicated thereon in favor of a patentee in a patent infringement action involving standard essential patents. In Fujitsu, the Court endorsed standard compliance as a way of proving infringement, holding that, if a district court construes the claims and finds that the reach of the claims includes any device that practices a standard, then this can be sufficient for a finding of infringement. In this case, the Court moved on to hold that standard-essentiality is a question for the factfinder (meaning judges in bench trials and juries in jury trials), rejecting the defendant’s argument that, under Fujitsu, the court must first make a threshold determination as part of claim construction that all implementations of a standard infringe the claims.

Details

I. background

In a patent infringement action for U.S. Patent Nos. 8,385,239 and 8,351,538 in the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware filed by Godo Kaisha IP Bridge 1 (“IP Bridge”) against TCL Communication Technology Holdings Ltd. et al. (“TCL”), asserted claims are directed to the Long-Term Evolution (“LTE”) standard, a standard for wireless broadband communication for mobile devices and data terminals, and IP Bridge’s infringement theory relied on Fujitsu Ltd. v. Netgear Inc., 620 F.3d 1321 (Fed. Cir. 2010), holding, on appeal from a summary judgment decision, that a district court may rely on an industry standard in analyzing infringement. Specifically, the Federal Circuit stated:

“We hold that a district court may rely on an industry standard in analyzing infringement. If a district court construes the claims and finds that the reach of the claims includes any device that practices a standard, then this can be sufficient for a finding of infringement. We agree that claims should be compared to the accused product to determine infringement. However, if an accused product operates in accordance with a standard, then comparing the claims to that standard is the same as comparing the claims to the accused product. We accepted this approach in [Dynacore Holdings Corp. v. U.S. Philips Corp., 363 F.3d 1263 (Fed.Cir.2004)] where the court held a claim not infringed by comparing it to an industry standard rather than an accused product. An accused infringer is free to either prove that the claims do not cover all implementations of the standard or to prove that it does not practice the standard.” Fujitsu, 620 F.3d at 1327.

IP Bridge presented evidence to show that (1) the asserted claims are essential to mandatory sections of the LTE standard; and (2) the accused products comply with the LTE standard. In contrast, TCL did not present any evidence to counter that showing.

After a jury trial in 2018, the jury found that TCL was liable for infringement of the asserted claims by its sale of LTE standard-compliant devices such as mobile phones and tablets. The jury also awarded IP Bridge damages in the amount of $950,000.

Following the verdict, TCL filed a motion for judgment as a matter of law (“JMOL”), contending that IP Bridge’s theory of infringement was flawed because the Fujitsu “narrow exception” to proving infringement in the standard way, and IP Bridge filed a motion to amend the judgment under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 59(e), seeking supplemental damages and an accounting of infringing sales of all adjudicated products through the date of the verdict, and ongoing royalties for TCL’s LTE standard-compliant products, “both adjudicated and non-adjudicated.”

The district court denied TCL’s JMOL motion, concluding that substantial evidence supported the jury’s infringement verdict. In contrast, the district court awarded the requested pre-verdict supplemental damages, and awarded on-going royalties in that amount for both the adjudicated products and certain unadjudicated products, with finding that the jury’s award represented a FRAND (Fair, Reasonable And Non-Discriminatory) royalty rate of $0.04 per patent per infringing product. The district court reasoned that, because IP Bridge demonstrated at trial that LTE standard-compliant devices do not operate on the LTE network without infringing the asserted claims, the unaccused, unadjudicated products “are not colorably different tha[n] the accused products.”

TCL timely appealed the district court’s infringement finding and its rulings regarding royalties.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit unanimously affirmed all aspects of the district court’s rulings and the verdict predicated thereon in favor of a patentee in a patent infringement action involving standard essential patents.

The issue in the appeal was a question not expressly answered by its case law including Fujitsu: who determines the standard-essentiality of the patent claims at issue—the court, as part of claim construction, or the jury, as part of its infringement analysis? The Court agreed with IP Bridge that standard-essentiality is a question for the factfinder.

TCL’s entire appeal rested on a single statement from Fujitsu, 620 F.3d at 1327: “If a district court construes the claims and finds that the reach of the claims includes any device that practices a standard, then this can be sufficient for a finding of infringement” (emphasis added). In TCL’s view, the statement mandates that a district court must first determine, as a matter of law and as part of claim construction, that the scope of the claims includes any device that practices the standard at issue.

The Court rejected TCL’s contention for three reasons below.

First, the Court pointed out that the statement in Fujitsu assumed the absence of genuine disputes of fact on the two steps of that analysis, which would be necessary to resolve the question at the summary judgment stage. The passing reference in Fujitsu to claim construction is simply a recognition of the fact that the first step in any infringement analysis is claim construction.

Second, the Court stated that its reading of Fujitsu is buttressed by that decision’s reference to Dynacore where the Court affirmed the summary judgment of non-infringement because the patentee did not show that a particular claim limitation was mandatory in the standard. The Court read Dynacore such that: “Although we referenced the claim construction by which the patentee was bound, Dynacore considered the possibility of the dispute going to the jury and rejected it based on undisputed facts.” Based on this, the Court concluded that, under Dynacore, which Fujitsu referenced in its holding, standard-essentiality of patent claims is a fact issue. The Court noted that the standard-essentiality may be amenable to resolution on summary judgment in appropriate cases like any other fact issue, but that it does not mean it becomes a question of law.

Finally, the Court expressed a view that determining standard-essentiality of patent claims during claim construction hardly makes sense from a practical point of view. Essentiality is, after all, a fact question about whether the claim elements read onto mandatory portions of a standard that standard-compliant devices must incorporate. In the Court’s view, this inquiry is more akin to an infringement analysis (comparing claim elements to an accused product) than to a claim construction analysis (focusing, to a large degree, on intrinsic evidence and saying what the claims mean).

From the foregoing, the Court found that substantial evidence fully supports the jury’s infringement verdict.

Further, the Court saw no reason to disturb the district court’s conclusions after carefully considering TCL’s remaining arguments—including its argument that the district court abused its discretion in awarding on-going royalties in this case.

In conclusion, the Court unanimously affirmed all aspects of the district court’s rulings and the verdict predicated thereon in favor of a patentee in a patent infringement action involving standard essential patents.

Takeaway

· In a patent infringement action involving standard essential patents, standard-essentiality is to be determined by judges in bench trials and juries in jury trials.

Proprietary interest is not required in seeking cancellation of a trademark registration

| August 31, 2020

Australian Therapeutic Supplies Pty. Ltd. v. Naked TM, LLC

July 27, 2020

O’Malley, Reyna, Wallach (Opinion by Reyna; Dissent by Wallach)

Summary

The Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (the “TTAB”) determined that Australian Therapeutic Supplies Pty. Ltd. (“Australian”) lacked standing to bring a cancellation proceeding against a trademark registration of Naked TM, LLC (“Naked”), because Australian lacked proprietary rights in its unregistered marks. The United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the “CAFC”) reversed and remanded, holding that proprietary interest is not required in seeking cancellation of a trademark registration. By demonstrating real interest in the cancellation proceeding and a reasonable belief of damage, statutory requirement to bring a cancellation proceeding under 15 U.S.C. § 1064 is satisfied.

Details

Australian started using the mark NAKED and NAKED CONDOM for condoms in Australia in early 2000. Australian then began advertising, selling, and shipping the goods bearing the marks to customers in the United States starting as early as April 2003.

Naked owns U.S. Trademark Registration No. 3,325,577 for the mark NAKED for condoms. In 2005, Australian became aware of the trademark application filed on September 22, 2003 by Naked’s predecessor-in-interest. On July 26, 2006, Australian contacted Naked, claiming its rights in its unregistered mark. From July 26, 2006 to early 2007, Australian and Naked engaged in settlement negotiations over email. Naked asserts that the email communications resulted in a settlement, whereby Australian would discontinue use of its unregistered mark in the United States, and Australian consents to Naked’s use and registration of its NAKED mark in the United States. Australian asserts the parties failed to agree on the final terms of a settlement, and no agreement exists.

In 2006, Australian filed a petition to cancel registration of he NAKED mark, asserting Australian’s prior use of the mark, seeking cancellation on the grounds of fraud, likelihood of confusion, false suggestion of a connection, and lack of bona fide intent to use the mark. Naked responded, denying the allegations and asserting affirmative defenses, one of which was that Australian lacked standing, as Australian was contractually and equitably estopped from pursuing the cancellation.

Following trial, on December 21, 2018, the Board concluded that Australian lacked standing to bring the cancellation proceeding, reasoning that Australian failed to establish proprietary rights in its unregistered mark and therefore, lacked standing. The Board found that while no formal written agreement existed, through email communications and parties’ actions, the Board found that Australian led Naked to reasonably believe that Australian had abandoned its rights to the NAKED mark in the United States in connection with condoms. While the Board made no finding on whether Australian agreed not to challenge Naked’s use and registration of the NAKED mark, the Board concluded that Australian lacked standing because it could not establish real interest in the cancellation or a reasonably basis to believe it would suffer damage from Naked’s continued registration of the mark NAKED.

The statutory requirements to bring a cancellation proceeding under 15 U.S.C. § 1064 are 1) demonstration of a real interest in the proceeding; and 2) a reasonable belief of damage. The CAFC held that the Board erred by concluding that Australian lacked standing because it had no proprietary rights in its unregistered mark. Australian contracting away its rights to use the NAKED mark in the United States could bar Australian from proving actual damage, the CAFC clarified that 15 U.S.C. § 1064 requires only a belief of damage. In sum, establishing proprietary rights is not a requirement for demonstrating a real interest in the proceeding and a belief of damage.

Next, the CAFC considered whether Australian has a real interest and reasonable belief of damage such that is has a cause of action under 15 U.S.C. § 1064. Here, Australian demonstrates a real interest because it had twice attempted to register its mark in 2005 and 2012, but was refused registration based on a likelihood of confusion with Naked’s registered mark. The USPTO has suspended prosecution of Australian’s later-filed application, pending termination of the cancellation proceeding, which further demonstrates a belief of damage.

Naked argued that Australian’s applications do not support a cause of action because Australian abandoned its first application. It also argued that ownership of a pending application does not provide standing.

With regard to the first point, the CAFC stated that abandoning prosecution does not signify abandoning of its rights in a mark. As for the second point, Australian’s advertising and sales in the United States since April 2003, supported by substantial evidence, demonstrate a real interest and reasonable belief of damage.

While Naked questions the sufficiency of Australian’s commercial activity, the CAFC stated that minimum threshold of commercial activity is not imposed by 15 U.S.C. § 1064.

Therefore, the CAFC held that the Board erred by requiring proprietary rights in order to establish a cause of action under 15 U.S.C. § 1064. The CAFC also held that based on the facts before the Board, Australian had real interest and a reasonable belief of damage; the statutory requirements for seeking a cancellation proceeding is thereby satisfied. The CAFC reversed and remanded the case to the Board for further proceedings.

Dissenting Opinion

While Judge Wallach, in his dissenting opinion agreed that proprietary interest is not required, he disagreed with the majority’s finding that Australian met its burden of proving a real interest and a reasonable belief in damages. In this case, any “legitimate commercial interest” in the NAKED mark was contracted away, as was any “reasonable belief in damages”.

Takeaway

Proprietary interest is not required in seeking cancellation of a trademark registration. Statutory requirement to bring a cancellation proceeding under 15 U.S.C. § 1064 is satisfied by demonstrating real interest in the cancellation proceeding and a reasonable belief of damage.

PTAB Should Provide Adequate Reasoning and Evidence in Its Decision and Teaching Away Argument Requires More Than a General Preference

| August 26, 2020

ALACRITECH, INC. V. INTEL CORP., CAVIUM, LLC, DELL, INC.

July 31, 2020

Before Stoll, Chen, and Moore

Summary

The Federal Circuit reviewed the adequacy of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s (Board) obviousness findings under the Administrative Procedure Act’s (APA) requirement that the Board’s decisions be supported by adequate reasoning and evidence. The Federal Circuit agreed with Alacritech’s argument that the Board did not adequately support the finding. The Federal Circuit found no reversible error in the Board’s remaining obviousness determination. The Federal Circuit vacated in part and remanded the Board’s decision.

Background

Alacritech, Inc. owns the patent 8,131,880. Intel Corp., et al., (Intel) petitioned to the Board for inter partes review (IPR) of the patent ‘880. The Board’s final decisions found the challenged claims unpatentable as obvious. Alacritech appealed the Board’s obviousness decision for four independent claims.

The ‘880 patent relates to computer networking and is directed to a network-related apparatus and method for offloading certain network processing from a central processing unit (CPU) to an “intelligent network interface card.” Intel asserted that the challenged claims would have been obvious over Thia1 in view of Tanenbaum2. The Board agreed and held all of the challenged claims unpatentable as obvious in the final written decisions. On appeal in the Federal Circuit, one of the focus was on claim 41 reciting “a flow re-assembler disposed in the network interface” as follows:

| 41. An apparatus for transferring a packet to a host computer system, comprising: a traffic classifier, disposed in a network interface for the host computer system, configured to classify a first packet received from a network by a communication flow that includes said first packet; a packet memory, disposed in the network interface, configured to store said first packet; a packet batching module, disposed in the network interface, configured to determine whether another packet in said packet memory belongs to said communication flow; a flow re-assembler, disposed in the network interface, configured to re-assemble a data portion of said first packet with a data portion of a second packet in said communication flow; and a processor, disposed in the network interface, that maintains a TCP connection for the communication flow, the TCP connection stored as a control block on the network interface. |

Discussion

Alacritech argued that the Board’s analysis was inadequate to support its findings on claims 41-43. Independent claim 43 is similar to claim 41, but recites a limitation in the network interface with “a re-assembler for storing data portions of said multiple packets without header portions in a first portion of said memory.” The dispute was focused on where reassembly takes place in the prior art and whether that location satisfies the claim limitations. The alleged claims incorporate limitations that require reassembly in the network interface, as opposed to a central processor. Intel argued that “Thia . . . discloses a flow re-assembler on the network interface to re-assemble data portions of packets within a communication flow.” In response, Alacritech argued that “[n]either Thia nor Tanenbaum discloses a flow re-assembler that is part of the NIC.”

The Board recited some of the parties’ arguments and concluded that the asserted prior art teaches the reassembly limitations. Alacritech argued that the Board’s analysis did not adequately support its obviousness finding. The Federal Circuit reviewed the adequacy of the Board’s obviousness finding under the APA’s requirement that the Board’s decisions be supported by adequate reasoning and evidence. The Federal Circuit emphasized that the Board’s findings need not be perfect, but must be “reasonably discernable.” However, the Board failed to meet the requirement by explaining why it found those arguments persuasive. The Federal Circuit reasoned that the Board briefly recites two terse paragraphs from the parties’ arguments and, in doing so, “appears to misapprehend both the scope of the claims and the parties’ arguments.” Further, the Federal Circuit turned down Intel’s argument that it should prevail because the Board “soundly rejected” Alacritech’s arguments. But the Board’s rejection does not necessarily support the Board’s finding that the asserted prior art teaches or suggests reassembly in the network interface. The Board should meet the obligation to “articulate a satisfactory explanation for its action including a rational connection between the facts found and the choice made.” The Federal Circuit, therefore, vacated the portion of the Board’s decision.

Alacritech successfully kept the ball rolling due to the Board’s inadequate reasoning and evidence. However, Alacritech did not substantially weaken the obviousness determination, and its teaching away argument on Tanenbaum hit the wall. Tanenbaum suggests on protocols for gigabit networks that “[u]sually, the best approach is to make the protocols simple and have the main CPU do the work.” Such a statement did not disparage other approaches. As pointed out by the Federal Court, “Tanenbaum merely expresses a preference and does not teach away from offloading processing from the CPU to a separate processor.”

The Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s finding of a motivation to combine Thia and Tanenbaum, explaining that “[a] reference that ‘merely expresses a general preference for an alternative invention but does not criticize, discredit, or otherwise discourage investigation into’ the claimed invention does not teach away.” (Meiresonne v. Google (Fed. Cir. March 7, 2017)) The proposition makes clear that a general preference cannot support teaching away argument. A proper teach away argument requires evidence that shows the prior art references would lead away from the claimed invention.

Takeaway

- The PTAB’s obviousness findings should meet the APA’s requirements to support its decisions with adequate reasoning and evidence.

- A proper teach away argument requires evidence that shows the prior art references would lead away from the claimed invention.

Full Federal Circuit Continues 101 Spin on Driveshaft Eligibility

| August 14, 2020

American Axle & Manufacturing v. Neapco Holdings – Part II

July 31, 2020

Opinion by: Dyke, Moore and Taranto

Dissent by: Moore

Summary:

A 6-6 split vote for en banc rehearing dooms clarification on the patent eligibility of a driveshaft manufacturing method by the full Federal Circuit. The petition for rehearing en banc for this case engendered 6 amici curiae briefs. The denial of en banc rehearing triggered 2 concurrences and 4 dissenting opinions.

Nevertheless, a new modified panel decision is issued, with different results than the first panel decision. While the first panel decision found representative claims 1 and 22 ineligible under 35 U.S.C. §101, this second panel decision still found claim 22 ineligible for essentially the same reasons as before, but remanded claim 1. Like the first panel decision, this new panel decision also includes a strong dissent by Judge Moore.

The conflicting positions of a split Federal Circuit in this case highlight the turmoil in current 101 jurisprudence.

Procedural History:

American Axle & Manufacturing, Inc. (AAM) sued Neapco Holdings, LLC (Neapco) for infringement of U.S. Patent 7,774,911 (the ‘911 patent) on a method of manufacturing driveline propeller shafts for automotive vehicles. On appeal, the Federal Circuit upheld the District Court of Delaware’s holding of invalidity under 35 U.S.C. §101 in the first panel decision issued October 3, 2019 (hereinafter, AAM I). A combined petition for panel rehearing and for en banc rehearing was filed. A modified, precedential, panel decision was issued on July 31, 2020 in response to the petition for panel rehearing (hereinafter, AAM II) – affirming the ineligibility of claim 22, its dependent claims and claim 36, but remanding claim 1 and its dependent claims to the district court. The petition for en banc rehearing was denied.

Background:

The ‘911 patent relates to a method for manufacturing driveline propeller shafts (“propshafts” that transmit power in a driveline) with liners that attenuate vibrations transmitted through a shaft assembly. During use, propshafts experience three types of vibration: bending mode vibration, torsion mode vibration, and shell mode vibration, each involving different frequencies. To attenuate the noise accompanying such vibration, various conventional methods using weights, dampers, and liners are inserted to frictionally engage the propshaft to dampen certain vibrations. However, such conventional dampening methods were designed to individually attenuate each of the three types of vibration. According to AAM, the ‘911 patent seeks to attenuate two vibration modes simultaneously, which the prior art did not do.

The CAFC focused on independent claims 1 and 22 as being “representative” claims:

| Claim 1 | Claim 22 |

| 1. A method for manufacturing a shaft assembly of a driveline system, the driveline system further including a first driveline component and a second driveline component, the shaft assembly being adapted to transmit torque between the first driveline component and the second driveline component, the method comprising: providing a hollow shaft member; tuning at least one liner to attenuate at least two types of vibration transmitted through the shaft member; and positioning the at least one liner within the shaft member such that the at least one liner is configured to damp shell mode vibrations in the shaft member by an amount that is greater than or equal to about 2%, and the at least one liner is also configured to damp bending mode vibrations in the shaft member, the at least one liner being tuned to within about ±20% of a bending mode natural frequency of the shaft assembly as installed in the driveline system. | 22. A method for manufacturing a shaft assembly of a driveline system, the driveline system further including a first driveline component and a second driveline component, the shaft assembly being adapted to transmit torque between the first driveline component and the second driveline component, the method comprising: providing a hollow shaft member; tuning a mass and a stiffness of at least one liner, and inserting the at least one liner into the shaft member; wherein the at least one liner is a tuned resistive absorber for attenuating shell mode vibrations and wherein the at least one liner is a tuned reactive absorber for attenuating bending mode vibrations. |

The district court construed claim 1’s “tuning at least one liner to attenuate at least two types of vibration transmitted through the shaft member” to mean “controlling characteristics of at least one liner to configure the liner to match a relevant frequency or frequencies to reduce at least two types of vibration transmitted through the shaft member” (emphasis in original). Claim 22’s “tuning a mass and a stiffness of at least one liner” was construed to mean “controlling the mass and stiffness of at least one liner to configure the liner to match the relevant frequency or frequencies.” Notably, the above claim interpretation for claim 1 was not mentioned in AAM I, and the district court made no distinction between claims 1 and 22 in its decision.

AAM II Panel Decision:

Claim 22

With regard to claim 22, the §101 analysis is essentially the same between AAM I and AAM II.

Under the Mayo/Alice step 1, claim 22 was deemed “directed to” Hooke’s law, mathematically relating mass and stiffness of an object to the frequency with which that object vibrates. Claim 22 merely recites “tuning a mass and a stiffness of at least one liner,” without any particular physical structures or steps for tuning. “[C]laim 22 here does not specify how target frequencies are determined or how, using that information, liners are tuned to attenuate two different vibration modes simultaneously, or how such liners are tuned to dampen bending mode vibrations.” As such, claim 22 is merely claiming a desired result (tuning a liner), without limitation to any particular structures or ways to achieve it. AAM II concludes, “[t]his holding as to step 1 of Alice extends only where, as here, a claim on its face clearly invokes a natural law, and nothing more, to achieve a claimed result.”

Notably absent from AAM II’s Alice step 1 analysis is the majority’s earlier reference in AAM I to Hooke’s law “and possibly other natural laws” in describing what natural law claim 22 is directed to.

Under the Mayo/Alice step 2, claim 22 does not recite an “inventive concept” to transform it into patent eligible subject matter. The majority summarizes AAM’s argument for an inventive concept to be merely a restatement of the desired results (tuned liners that dampen two different vibration modes simultaneously) being an advance. However, an ineligible concept cannot supply the inventive concept. And the remaining steps in claim 22 are merely conventional pre- and post-solution activity.

Claim 1

With regard to claim 1, the majority focused on three differences from claim 22.

One difference is that claim 1’s feature of “tuning at least one liner to attenuate at least two types of vibration transmitted through the shaft member” was construed by the district court to mean “controlling characteristics of at least one liner to configure the liner to match a relevant frequency or frequencies to reduce at least two types of vibration transmitted through the shaft member” (emphasis in original). Claim 22 did not require “controlling characteristics…”

Second, such “characteristics” are described in the specification to include variables other than mass and stiffness, including length and outer diameter of the liner 204, diameter and wall thickness of a structural portion 300 and the material thereof, quantity of resilient member(s) 302 and the material thereof, a helix angle 330 and pitch 332 with which resilient members 302 are fixed to the structural portion 300, the configuration of lip member(s) 322 of the resilient member 302, and the location of the liners 204 within the shaft member 200. Claim 22 did not go beyond tuning involving mass and stiffness.

Third, claim 1 requires “positioning the at least one liner.” The majority considered claim 22’s “inserting the at least one liner into the shaft member” as not being equivalent to claim 1’s “positioning” feature, without explanation. On this point, J. Moore, noted in the dissent, that this is improper sua sponte appellate claim construction which neither parties briefed nor argued. J. Moore argued claim 22’s ineligibility should not have been premised on such unsupported sua sponte claim construction.

Because of these differences, the majority held that claim 1 is not merely directed to Hooke’s law “and nothing more.” “The mere fact that any embodiment practicing claim 1 necessarily involves usage of one or more natural laws is by itself insufficient to conclude the claim is directed to such natural laws.”

But, this doesn’t mean that claim 1 is eligible. The majority notes that the district court and Neapco also raised ineligibility based on the judicial exception for an abstract idea. “But the abstract idea basis was not adequately presented and litigated in the district court.” Thus, the majority remanded the claim 1 and its dependent claims to the district court to address this abstract idea issue in the first instance.

J. Moore’s Dissent:

Like in AAM I, J. Moore’s dissent in AAM II is likewise stinging. “The majority’s decision expands §101 well beyond its statutory gate-keeping function and collapses the Alice/Mayo two-part test to a single step – claims are now ineligible if their performance would involve application of a natural law.”

- A new “Nothing More test”

J. Moore asserts that the majority created a new test, a “Nothing More test” – “when claims are directed to a natural law despite no natural law being recited in the claims.” According to the majority, claim 22’s “tuning” feature meant “controlling the mass and stiffness of at least one liner to configure the liner to match the relevant frequency or frequencies” and “[t]hus, claim 22 requires use of a natural law of relating frequency to mass and stiffness – i.e., Hooke’s law.” However, J. Moore notes that “[e]very mechanical invention requires use and application of the laws of physics. It cannot suffice to hold a claim directed to a natural law simply because compliance with a natural law is required to practice the method.”

“Section 101 is monstrous enough, it cannot be that use of an unclaimed natural law in the performance of an industrial process is sufficient to hold the claims directed to that natural law.” “All physical methods must comply with, and apply, the laws of physics and the laws of thermodynamics…[t]he fact that they do does not mean the claims are directed to all such laws.” “This case turns the gatekeeper into a barricade. Unstated natural laws lurk in the operation of every claimed invention. Given the majority’s application of its new test, most patent claims will now be open to a §101 challenge for being directed to a natural law or phenomena.”

The majority’s counterpoint: “If patentees could avoid the natural law exception by failing to recite the law itself [like here – no mention of ‘Hooke’s law’, but varying frequency attenuation (tuning) based on mass and stiffness is on its face Hooke’s law], patent eligibility would depend upon the ‘draftsman’s art,’ the very approach that Mayo rejected.”

However, avoiding the “draftsman’s art” is not the primary focus of §101. Instead, it is on preemption. That is why claims may be patent eligible under §101 if the “claimed advance” reflects an improvement in technology. As J. Moore also noted, “[t]he claims at issue contain a specific, concrete solution (inserting a liner inside a propshaft) to a problem (vibrations in propshafts).” The ‘911 claims are directed to the traditional manufacturing of a drive shaft assembly for a car, which have historically avoided any concern under §101. On this point, see also J. Stoll’s dissent on the denial of en banc rehearing below.

Another problem with the majority’s new “Nothing More test” is that it arguably requires appellate judges to “resolve questions of science de novo on appeal.” J. Moore raises a concern about appellate judges making determinations of scientific fact on appeal, in the first instance, as a matter law. Nothing in the intrinsic record (nothing in the patent and nothing in the prosecution history) mentions Hooke’s law. So, “how can we conclude, as a matter of law, the claim nonetheless clearly invokes Hooke’s law?” To J. Moore, “judges are not fact or technical experts…[t]he only appropriate fact finder is the district court and not on summary judgment.”

Indeed, during litigation both sides’ experts and the district court noted that the claims involve Hooke’s law and friction damping. Yet, the majority concludes that the natural law used is Hooke’s law “and nothing more.” The majority’s counterpoint is that even “[i]f claim 22’s language could be properly interpreted in a way such that it invokes friction damping as it does with Hooke’s law, the claims would still on its face clearly invoke natural laws, and nothing more, to achieve a claimed result.”

“A disturbing amount of confusion will surely be caused by this opinion, which stands for the proposition that claims can be ineligible as directed to a natural law even though no actual natural law is articulated in the claim or even the specification. The majority holds that claims are directed to a natural law if performance of the claimed method would use the natural law.”

- Failure to consider unconventional claim elements under Mayo/Alice step 2

Under the Mayo/Alice step 2 analysis, while the majority asserts that “[w]hat is missing is any physical structure or steps for achieving the claimed result,” J. Moore notes that AAM’s arguments identified “many” inventive concepts that should have at least precluded summary judgment. For instance, AAM argued that liners (a physical and explicitly recited claim element) were never before used to reduce bending mode vibrations. Instead of addressing all the inventive concepts laid out by AAM, “the majority creates its own strawman to knock down” (i.e., sophisticated FEA software and computer modeling that are not claimed).

- Enablement on Steroids

“[T]he majority has imbued §101 with a new superpower – enablement on steroids.” “The majority’s concern is not preemption of a natural law (which should be the focus), but rather that the claims do not teach a skilled artisan how to tune a liner without trial and error. The majority’s blended 101/112 defense is confusing, converts fact questions into legal ones and eliminates the knowledge of a skilled artisan.”

Of course, the majority clarified that there is a “how to” 1 and a “how to” 2. The “how to” 1 is a requirement under 101 that “the claim itself (whether by its own words or by statutory incorporation of specification details under section 112(f)) must go beyond stating a functional result: it must identify ‘how’ that functional result is achieved by limiting the claim scope to structures specified at some level of concreteness, in the case of a product claim, or to concrete action, in the case of a method claim.” The “how to” 2 is a different requirement that applies to the specification under §112, not to the claim. But, see, J. Stoll’s dissent below. At what level of specificity is sufficient to pass muster under the majority’s “how to” 1? How is this to be determined, absent any input by a skilled artisan? Doesn’t this “how to” inquiry involve questions of fact which should not be determined de novo as a matter of law by appellate judges?

Concurring and Dissenting Opinions on the Denial of en banc Rehearing:

J. Dyk’s concurrence argues that this modified panel decision is consistent with precedent and that there was no “new” test.

J. Chen’s concurrence also states that the panel majority’s decision is consistent with long-standing precedent, and there was no new patent-eligibility test. And, “[a]s evidenced by the majority opinion’s conclusion that claim 1 is not directed to a natural law, the narrow holding of this case should not be read to open the door to eligibility challenges based on the argument that a claim is directed to one or more unspecified natural laws.” J. Chen also disagrees about 101 being enablement on steroids, “result-oriented claim drafting raises concerns under section 101 independent from section 112.” “The lesson to patent drafters should now be clear: while not all functional claiming is the same, simply reciting a functional result at the point of novelty poses serious risks under section 101.”

J. Newman’s dissent stated “[t]he court’s new spin on Section 101 holds that when technological advance is claimed too broadly, and the claims draw on scientific principles, the subject matter is barred ‘at the threshold’ from access to patenting.” This is contrary to the warning in Alice to be careful to avoid oversimplifying the claims because ‘[a]t some level, ‘all inventions…embody, use, reflect, rest upon, or apply laws of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract ideas.’” “The court’s notion that the presence of a scientific explanation of an invention removes novel and non-obvious technological advance from access to the patent system, has moved the system of patents from its once-reliable incentive to innovation and commerce, to a litigation gamble.”

J. Stoll’s dissent makes notable challenges to the majority’s “how to” analysis in §101’s directed to inquiry:

“Even assuming that claim 22 applies Hooke’s law (or any other unnamed law of nature), the claim seems sufficiently specific to qualify as an eligible application of that natural law. The claim identifies specific variables to tune, including ‘a mass and a stiffness of at least one liner.’ It requires that the tuned liner attenuate specific types of vibration, including ‘shell mode vibrations’ and ‘bending mode vibrations,’ and further requires that the tuned liner is inserted in a ‘hollow shaft member.’ With this level of specificity, claim 22 appears to be properly directed to ‘the application of the law of nature to a new and useful end,’ not to the law of nature itself. Yet this level of detail is insufficient in the majority’s view, and it remains unclear how much more ‘how to’ would have been sufficient to render the claim eligible under the majority’s approach.” (citations omitted).

J. Stoll also remarked, “[i]n my view, the result in this case suggests that this court has strayed too far from the preemption concerns that motivate the judicial exception to patent eligibility.”

J. O’Malley’s dissent identifies at least three problems in the majority opinion: “(1) it announces a new test for patentable subject matter at the eleventh hour and without adequate briefing; (2) rather than remand to the district court to decide the issue in the first instance, it applies the new test itself; and (3) it sua sponte construes previously undisputed terms in a goal-oriented effort to distinguish claims and render them patent ineligible, or effectively so.”

Takeaways:

- Even in traditionally eligible industrial and mechanical inventions, potential §101 issues may now be raised depending on the scope of the functional claiming being used, especially if result-oriented. J. Stoll expressed legitimate concerns about the practical effect of this modified panel decision, “[a]lthough the majority has dialed back its original decision to some degree on panel rehearing, one can still reasonably ponder whether foundational inventions like the telegraph, telephone, light bulb, and airplane – all of which employ laws of nature – would have been ineligible for patenting under the majority’s revised approach.”

- But, don’t give up. Whether defending a patent or challenging a patent on §101, the Federal Circuit is clearly split on various issues under 101. Unfortunately, §101 jurisprudence is, as J. Newman remarked, becoming a “litigation gamble.” Nevertheless, depending on who is on your panel, you may get a favorable decision. Only the Supreme Court or Congress can come to the rescue of §101.

- This case is a reminder that claim construction can change the result of the 101 determination.

- As J. Chen noted, functional, result-oriented, claiming, especially at the point of novelty, may trigger serious 101 issues, even in mechanical cases that, until now, were mostly immune to §101 attack.

- Try to include a “kitchen sink” claim. The specificity provided may help overcome such 101 issues.

- Perhaps AAM never expected such results for its independent claims. But, another lesson learned from this case is to try to preserve arguments based on the dependent claims and challenge the characterization of the “representative” claim if possible.

WALKING DEAD PATENT CLAIMS IN AN IPR

| July 31, 2020

UNILOC 2017 LLC v. HULU, LLC, NETFLIX, INC

July 22, 2020

This precedential decision is made particularly interesting based on the dissenting opinion by Judge O’Malley pointing out that the CAFC’s affirmance of a district court’s ineligibility determination in a related district court proceeding makes the case moot, as there are no remaining challenged claims to replace with substitute claims. More specifically, when Uniloc did not seek Supreme Court review of the district court’s ineligibility determination, the appeal should have been dismissed as moot (“[A]n appeal should … be dismissed as moot, when, by virtue of an intervening event, a court of appeals cannot grant any effectual relief whatever in favor of the appellant.” Calderon v. Moore, 518 U.S. 149, 150 (1996) (quotation marks omitted). The majority opinion, however, treats the merits of the case (since Hulu had not filed anything contending that the PTAB had lost authority) and finds that §101 can be considered in an IPR with respect to substitute claims.

Background

To better understand the issues surrounding this case, it is necessary to piece together the complete background from both the majority and dissenting opinions. In 2016, Uniloc filed several lawsuits in the Eastern District of Texas alleging infringement of the claims of its U.S. Patent No. 8,556, 960 (the ‘960 patent). In March 2017, the district court dismissed the cases for failure to state a claim, holding all claims patent ineligible under §101. Uniloc appealed and the CAFC summarily affirmed the district court decision on August 9, 2018. Uniloc did not seek Supreme Court review.

The PTAB had instituted an inter partes review (IPR) of claims 1-25 of the ‘960 patent in August 2017. On August 1, 2018, the PTAB issued a final written decision (FWD) finding claims 1-8, 18-22, and 25 unpatentable over prior art. Prior to the FWD, Uniloc had filed a Motion to Amend asking the PTAB to enter substitute claims 26-28 for claims 1, 22 and 25 if the PTAB found the latter unpatentable. Hulu opposed the motion, arguing among other things that the substitute claims were directed to patent-ineligible subject matter. Uniloc replied that Hulu was not permitted to raise §101 in an IPR and did not respond substantively to the §101 issue.

The PTAB concluded that it could analyze the §101 issue with respect to the substitute claims. The PTAB denied Uniloc’s Motion to Amend concluding that Hulu had shown by a preponderance of the evidence that the substitute claims were directed to non-statutory subject matter under §101, which was the sole ground for denying the motion to amend. Uniloc had opposed the motion merely by arguing that §101 cannot be considered without addressing the merits of §101.

Uniloc requested rehearing of the PTAB’s decision on August 31, 2018, as to only the proposed amended claims, which was denied on January 18, 2019. At the time of this denial, the time for seeking Supreme Court review of the August 9, 2018 CAFC decision had run. It could be said that at this point all claims of the ‘960 patent were dead. As such, by treating the merits of the case, these dead claims have the possibility of being resurrected by entry of substitute claims.

The panel consisted of Wallach, Taranto and O’Malley. Wallach filed the opinion for the majority and O’Malley filed the dissenting opinion.

The Majority Opinion

The majority opinion noted that Hulu had filed nothing as of August 31, 2018, contending that the PTAB had lost any authority to consider the substitute claims “given the final federal-court invalidation of the original claims – a contention that would have called for vacatur of the Final Written Decision rather than a denial of rehearing.” The majority opinion held that the case is not moot as it is possible to “grant effectual relief”, reasoning that if Uniloc is correct that the PTAB is statutorily barred from rejecting a substitute claim based on §101, then it is entitled to adding those claims because §101 was the only ground for finding unpatentability. The majority further pointed out that Hulu had waived its arguments that the final federal-court judgment of invalidity of the claims took the authority away from the USPTO to consider the substitute claims. Hulu did not argue to the PTAB in response to Uniloc’s petition for rehearing (which was filed after the federal-court invalidity judgment became final) that the PTAB had lost authority.[1] The majority noted that Congress did not carry forward pre-AIA § 317(b) concerning the termination of inter partes reexamination based on parallel judicial proceedings.

Having concluded that the CAFC had jurisdiction, the majority concluded that the PTAB was authorized by statute to assess substitute claims for eligibility under §101. The majority held that the PTAB correctly concluded that it is not limited by §311(b) in its review of proposed substitute claims in an IPR. The majority explained that the “determination is supported by the text, structure, and history of the IPR Statutes, which indicate Congress’s unambiguous intent to permit the PTAB to review proposed substitute claims more broadly than those bases provided in §311(b).” Among the reasoning noted in the opinion, “if a patent owner seeking amendments in an IPR were not bound by § 101 and §112, then in virtually any case, it could overcome prior art and obtain new claims simply by going outside the boundaries of patent eligibility and the invention described in the specification.”

O’Malley’s Dissent

O’Malley began her dissent by pointing out:

Typically, when this court has finally adjudged a patent claim as invalid, it also refuses to consider any appeal that demands relief dependent on that claim and vacates any such relief that has been awarded by another tribunal.

As such, O’Malley considers that the majority breathes life into a dead patent “and uses the zombie it has created as a means to dramatically expand the scope of inter partes review”. As such, O’Malley considers the PTAB to have been estopped from issuing substitute claims in place of the invalidated claims, and that even if the PTAB could issue such claims, it is improper to consider §101.

O’Malley first points out that the case is moot based on an intervening event (the final federal-court decision of unpatentability of all claims). O’Malley explains, contrary to the majority, that relief is only possible in the event of a remand to allow the PTAB authority to issue substitute claims.

After our affirmance of the district court’s ineligibility determination, and once the time expired for Uniloc to seek Supreme Court review of that affirmance, it did not possess any patent rights that it could give up in exchange for a substitute claim.

As such, the question is whether the Board can consider a request for substitute claims where, in a parallel proceeding with a final judgment, the original claims have been held invalid.

O’Malley further considers that the patent owner can only propose narrowed claims that address the issues raised in the petition, and therefor IPRs are limited to §§ 102 and 103. The language of the statute clearly prohibits consideration of patentability challenges other than §§ 102 and 103.

O’Malley further notes that IPRs were intended to be an efficient, cost-effective means of adjudicating patent validity. The majority opinion “opens substitute claims to an examination equivalent to that undertaken during patent prosecution, in an inter partes environment.”

One last notable quote:

This case was dead on arrival—there were no live claims remaining in the ’960 patent. I see the dead patent for what it is—a legal nullity incapable of supporting any further proceedings. I would end the case with that revelation. The majority, however, views the ’960 patent as an opportunity and takes it. It declares that dead patents can walk, at least as far as needed to die again on the same § 101 sword that killed it two years ago. That sword, however, does not exist in the IPR context. The Board can cancel claims and find proposed substitute claims unpatentable, certainly. It simply does not have statutory authority to do so based on § 101. Accordingly, I dissent.

Takeaways

This case likely would have been considered moot had Hulu at least filed some argument when the federal-court decision had become final and therefore the PTAB no longer had authority to act. Furthermore, Uniloc could have placed itself in a better position during the IPR by responding substantively that its substitute claims meet the standards for eligibility even though it was not yet clear whether § 101 could be considered. A different outcome is certainly possible had the timing of the related proceedings had been different.

[1] In inter partes reexamination (pre-AIA), a petition to dismiss the proceeding can be filed upon a final judgment in a concurrent federal proceeding. The author had successfully ended two inter partes reexaminations by filing such petitions.

CAFC Remands Back To PTAB Instructing Them To Conduct The Analysis And Correct The Mistakes In Wearable Technology IPR Case

| July 22, 2020

Fitbit, Inc., v. Valencell. Inc.

July 8, 2020

Before Newman, Dyk and Reyna. Opinion by Newman

Background:

Apple Inc., petitioned the Board for IPR (Inter Partes Review) of claims 1 to 13 of the U.S. Patent No., 8,923,941 (the ‘941 patent) owned by Valencell, Inc. The Board granted the petition in part, instituting review of claims 1, 2 and 6 to 13, but denying claims 3 to 5.

Fitbit then filed an IPR petition for claims 1, 2 and 6 to 13, and moved for joinder with Apple. The Board granted Fitbit’s petition and granted the motion for joinder.

After the PTAB trial, but before the Final Written Decision, the Supreme Court decided SAS Insitute, Inc., v. Iancu, 138 S. Ct 1348 (2018), holding that all patent claims challenged in an IPR petition must be reviewed by the Board, if the petition is granted. Thus, the Board re-instituted the Apple/Fitbit IPR to add claims 3 to 5.