Sorry Doc, no Patent Term Adjustment under the C-delay Provision!

| March 1, 2021

Steven C. Chudik vs., Andrew Hirshfeld (performing the functions & duties of the under Secretary of Commerce for IP and Director of the US.PTO).

February 8, 2021

Bryson, Hughes, and Taranto (author).

Summary:

i. Background:

Dr. Chudik filed his patent application before the USPTO on September 29, 2006.

After the issuance of a second rejection in 2010 “Dr. Chudik took a step that would turn out to have consequences for the patent term adjustment awarded under 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)” by requesting continued examination rather than “immediately taking an appeal to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board.”

Then in 2014, the Examiner again rejected the claims and Dr. Chudik appealed to the Board. As a result, the Examiner reopened prosecution and issued a subsequent office action rejecting the claims as unpatentable on a different ground.

Two more times Dr. Chudik appealed and each time the Examiner reopened prosecution and issued a new rejection.

In December 2017, while a fourth notice of appeal was pending, the Examiner withdrew several rejections; and after some claim amendments, the Examiner issued a Notice of Allowance in 2018. The application issued as a patent on May 15, 2018, eleven and a half years (11.5 yrs) after the patent application was originally filed.

Dr Chudick was given a patent term adjustment of 2,066 days under 35 U.S.C. § 154(b). The PTO rejected Dr. Chudik’s argument that “he was entitled to an additional 655 days, under 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(1)(C)(iii) (C-delay), for the time his four notice of appeals were pending.

ii. Issues:

Is Dr. Chuick entitled to patent term adjustment under 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(1)(C)(iii) (C-delay) for the time his four notice of appeals were pending, even though each time prosecution was reopened, and the case never proceeded to the Board?

iii. Holding

No, the CAFC agreed with the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia in affirming that Dr. Chudick was not entitled to the additional PTA under the C-delay provision. Chudik v. Iancu, No. 1:19-cv-01163 (E.D. Va. March 25, 2020), ECF No. 33.

The C-delay provision covers delays due to “appellate review by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board or by a Federal court in a case in which the patent was issued under a decision in the review reversing an adverse determination of patentability.” 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(1)(C)(iii).

The District Court held and the CAFC affirmed that the provision does not apply here because the Examiner reopened prosecution after each Notice of Appeal and so (1) the Board did not review the patent at issue and thus “the Board’s jurisdiction over the appeal never attached,” and as a consequence “(2) there was no reversal of the rejection by the Board.”

Dr. Chudick “argued that [the] C-delay applies in situations of “appellate review,” which, he urged, refers to the entire process for review by the Board, beginning when a notice of appeal is filed.”

The District Court rejected this argument and the CAFC agreed holding that the statutory language for “appellate review” requires a “decision in the review reversing an adverse determination of patentability.” 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(1)(C)(iii), and that language is both “reasonably” and “best interpreted” to require an actual “reversal decision made by the Board.” Consequently, the language excludes the “time spent on a path pursuing such a decision when, because of an examiner reopening of prosecution, no such decision is ever issued.”

The CAFC noted that “[W]hen adopting its 2012 regulations, the PTO explained that the limitations on C-delay adjustments… may be offset by an increased availability of B-delay adjustments.” However, for Dr. Chudik a B-delay increase fails to apply because rather than appealing his initial 2010 final rejection, a request for continued examination was filed and so the statutory exclusion was triggered. See 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(1)(B)(i) (excluding “any time consumed by continued examination of the application requested by the applicant under [35 U.S.C. § 132(b)]”).

The CAFC concluded that “[T]he unavailability of B-delay for nearly two years (655 days) of delay in the PTO illustrates what applicants should understand when deciding whether to request a continued examination rather than take an immediate appeal. The potential benefit of immediate re-engagement with the examiner through such continued examination comes with a potential cost.”

Additional Note:

Congress set forth three broad categories of delay for which a patent may receive a patent term adjustment. See 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(1)(A)–(C).

First, under § 154(b)(1)(A), a patent owner may seek an adjustment where the PTO fails to meet certain prescribed deadlines for its actions during prosecution.

Second, under § 154(b)(1)(B), adjustment is generally authorized for each day that the patent application’s pendency extends beyond three years (B-delay), subject to certain exclusions, such as for “time consumed by continued examination of the application requested by the applicant under section 132(b).”

Third, under § 154(b)(1)(C), a patent owner may seek an adjustment for “delays due to derivation proceedings, secrecy orders, and appeals,” including “appellate review by the [Board] . . . in a case in which the patent was issued under a decision in the review reversing an adverse determination of patentability” (C-delay).

Take-away:

- Where no new amendments and/or evidence is to be presented, carefully consider the balance between “[T]he potential benefit of immediate re-engagement with the examiner through such continued examination” and the “potential cost” thereof with respect to lost PTA under the B-delay exclusion.

- C-delay provision only applies when “the Board’s jurisdiction over the appeal” attaches and there is a reversal of the Examiner’s rejection.

Motion detection system found to be ineligible patent subject matter

| February 18, 2021

iLife Technologies v. Nintendo

January 13, 2021

Moore, Reyna and Chen. Opinion by Moore.

Summary:

iLife sued Nintendo for infringing its patent to a motion detection system. Claim 1 of the patent recites a motion detection system that evaluates relative movement of a body based on both dynamic and static acceleration, and a processor that determines whether body movement is within environmental tolerance and generates tolerance indica, and then the system transmits the tolerance indica. In granting Nintendo’s motion for JMOL, the district court held that claim 1 of iLife’s patent is directed to patent ineligible subject matter under § 101. The CAFC affirmed the district court stating that claim 1 of the patent is directed to the abstract idea of “gathering, processing, and transmitting information” and no other elements of claim 1 transform the nature of the claim into patent-eligible subject matter.

Details:

The patent at issue in this case is U.S. Patent No. 6,864,796 to a motion detection system owned by iLife. iLife sued Nintendo for infringement of claim 1 of the ‘796 patent. Claim 1 of the ‘796 patent is provided:

1. A system within a communications device capable of evaluating movement of a body relative to an environment, said system comprising:

a sensor, associable with said body, that senses dynamic and static accelerative phenomena of said body, and

a processor, associated with said sensor, that processes said sensed dynamic and static accelerative phenomena as a function of at least one accelerative event characteristic to thereby determine whether said evaluated body movement is within environmental tolerance

wherein said processor generates tolerance indicia in response to said determination; and

wherein said communication device transmits said tolerance indicia.

Nintendo moved for summary judgment arguing that claim 1 is directed to patent ineligible subject matter. The district court declined to decide the eligibility issue on summary judgment and the case proceeded to a jury trial. After a jury verdict in favor of iLife, Nintendo moved for a judgment as a matter of law (JMOL) again arguing patent ineligibility. The district court granted Nintendo’s motion for JMOL holding that claim 1 is directed to ineligible subject matter.

The CAFC followed the two-step test under Alice for determining patent eligibility.

1. Determine whether the claims at issue are directed to a patent-ineligible concept such as laws of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract ideas. If so, proceed to step 2.

2. Examine the elements of each claim both individually and as an ordered combination to determine whether the claim contains an inventive concept sufficient to transform the nature of the claims into a patent-eligible application. If the claim elements involve well-understood, routine and conventional activity they do not constitute an inventive concept.

Under step one, iLife argued that claim 1 is not directed to an abstract idea because claim 1 recites “a physical system that incorporates sensors and improved techniques for using raw sensor data” in attempt to analogize with Thales Visionix Inc. v. United States, 850 F.3d 1343 (Fed. Cir. 2017) and Cardio-Net, LLC v. InfoBionic, Inc., 955 F.3d 1358 (Fed. Cir. 2020). However, the CAFC distinguished Thales because in Thales, “the claims recited a particular configuration of inertial sensors and a specific choice of reference frame in order to more accurately calculate position and orientation of an object on a moving platform.” The court in Thales held that the claims were directed to an unconventional configuration of sensors.”

The CAFC also distinguished Cardio-Net because the claims in that case were “focused on a specific means or method that improved cardiac monitoring technology, improving the detection of, and allowing more reliable and immediate treatment of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter.” The CAFC started that claim 1 of the ‘796 patent “is not focused on a specific means or method to improve motion sensor systems, nor is it directed to a specific physical configuration of sensors.” Thus, the CAFC concluded that claim 1 is directed to the abstract idea of “gathering, processing, and transmitting information.”

Under step two, the CAFC stated that “[a]side from the abstract idea, the claim recites only generic computer components, including a sensor, a processor, and a communication device.” The CAFC also reviewed the specification finding that these elements are all generic. iLife attempted to argue that “configuring an acceleration-based sensor and processor to detect and distinguish body movement as a function of both dynamic and static acceleration is an inventive concept.” But the CAFC pointed out that the specification describes that sensors that measure both static and dynamic acceleration were known. The CAFC further stated that “claim 1 does not recite any unconventional means or method for configuring or processing that information to distinguish body movement based on dynamic and static acceleration. Thus, the CAFC concluded that merely sensing and processing static and dynamic acceleration information using generic components “does not transform the nature of claim 1 into patent eligible subject matter.”

Comments

When drafting patent applications, make sure to include specific details for performing particular functions and/or specific configurations. Claims including details about performing functions or about specific configurations will have a better chance to survive step one of the Alice test for patent eligibility. The specification should also include descriptions of why the specific functions or configurations provide improvements over the prior art to be able to show that the claims provide an “inventive concept” under step two of Alice.

“Kitchen” Sinks QuikTrip’s Trademark Opposition: The Federal Circuit Explains that Although Trademarks are Evaluated in their Entireties, when Determining Similarities between Trademarks, More Weight Is Applied to Distinctive Aspects of the Trademarks

| January 20, 2021

Quiktrip West, Inc. v. Weigel Stores, Inc

January 7, 2021

Lourie, O’Malley, and Reyna, (Opinion by Lourie)

Summary

QuikTrip filed a trademark opposition in the U.S. Patent & Trademarks Office (U.S.P.T.O.) against Weigel in relation to Weigel’s application for the trademark W Kitchens based on QuikTrip’s assertion that Weigel’s trademark is likely to cause confusion in relation to Quiktrip’s registered trademark QT Kitchen. The Board at the U.S.P.T.O. found that the dissimilarity of the marks weighed against the likelihood of confusion and dismissed QuikTrip’s opposition. On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s decision. The Federal Circuit explained that the Board correctly evaluated the trademarks in their entireties, while properly giving lower weight to less distinctive aspects of the trademark, such as the term “kitchen.” The Federal Circuit also noted that although some evidence suggested that Weigel may have copied QuikTrip’s trademark, the fact that Weigel modified its trademark multiple times in response to QuikTrip’s allegations of infringement negated any inference of an intent to deceive or cause confusion.

Background

- The Factual Setting

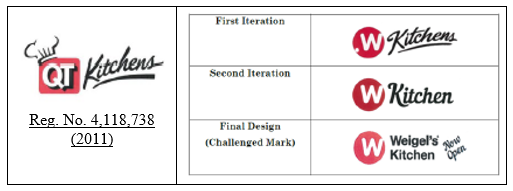

QuikTrip operates a combination gasoline and convenience store, and has sold food and beverages under its registered mark QT Kitchens (shown below left) since 2011.

In 2014, Weigel started using the stylized mark W Kitchens shown at the top-right below (First Iteration). QuikTrip sent Weigel a cease-and-desist letter. In response, Weigel adapted its mark to change Kitchens to Kitchen and to adapt the stylizing as shown at the middle-right below (Second Iteration). In response, QuikTrip demanded further modification by Weigel, and Weigel again adapted its mark to further change the font, to add its’ name Weigel’s and to include “new open” as shown at the bottom-right below (Final Challenged Mark).

The U.S.P.T.O. Proceedings

Weigel applied to register its’ Final Challenged Mark with the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (application no. 87/324,199), and QuikTrip filed an opposition to Weigel’s mark under 15 U.S.C. 1052(d) asserting that it would create a likelihood of confusion with its QT Kitchens mark.

The Board evaluated the likelihood of confusion and found that the dissimilarity of the marks weighed against the likelihood of confusion and dismissed QuikTrip’s opposition to Weigel’s registration of its mark.

QuikTrip appealed the Board’s decision to the Federal Circuit.

The Federal Circuit’s Decision

The Federal Circuit reviews the Board’s legal determination de novo, but reviews the underlying findings of fact based on substantial evidence.

Here, the legal analysis involves the determination of whether the mark being sought is “likely, when used on or in connection with the goods of the applicant, to cause confusion” with another registered mark. See 15 U.S.C. 1052(d) of the Lanham Act. The likelihood of confusion evaluation is a legal determination based on underlying findings of fact relating to the longstanding factors set forth in E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., 476 F. 2d 1357 (C.C.P.A. 1973). For reference, these factors include:

- The similarity of the marks (e.g., as viewed in their entireties as to their appearance, sound, connotation, and commercial impression);

2. The similarity and nature of the goods and services;

3. The similarity of the established trade channels;

4. The conditions under which, and buyers to whom, sales are made (e.g., impulse

verses sophisticated purchasing);

5. The fame of the prior mark;

6. The number and nature of similar marks in use on similar goods (e.g., by 3rd

parties);

7. The nature and extent of any actual confusion;

8. The length of time during, and the conditions under which, there has been

concurrent use without evidence of actual confusion;

9. The variety of goods on which a mark is or is not used;

10. The market interface between the applicant and the owner of a prior mark;

11. The extent to which applicant has a right to exclude others from use of its mark;

12. The extent of possible confusion;

13. Any other established fact probative of the effect of use.

On Appeal, QuikTrip challenges the Board’s analysis regarding the Dupont factor number one (1) based on “similarity of the marks” and the Dupont factor thirteen (13) based on “other established fact probative of the effect of use” which other fact is asserted by QuikTrip as being the “bad faith” of Weigel.

- Factor 1 (Similarity of the Marks)

With respect to the first factor pertaining to the similarity of the marks, QuikTrip asserted that the Board incorrectly “dissected the marks when analyzing their similarity” rather than rendering its determination based on the similarity of “the marks in their entireties.”

First, QuikTrip argued that the Board improperly “ignored the substantial similarity created by … the shared word Kitchen(s)” and gave “undue weigh to other dissimilar portions of the marks.” In response, the Federal Circuit explained that “[i]t is not improper for the Board to determine that ‘for rational reasons’ it should give ‘more or less weight’ to a particular feature of the mark” as long as “its ultimate conclusion … rests on a consideration of the marks in their entireties.”

Here, the Federal Circuit indicated that the portion “Kitchen(s)” should “accord less weight” because “kitchen” is a “highly suggestive, if not descriptive, word” and also because there were numerous “third-party uses, and third-party registrations of marks incorporating the word “kitchen” for sale of food and food-related services.”

Moreover, the Federal Circuit explained that “the Board was entitled to afford more weight to the dominant, distinct portions of the marks” which included “Weigel’s encircled W next to the surname Weigel’s and QuikTrip’s QT in a square below a chef’s hat” emphasizing “given their prominent placement, unique design and color.”

The Federal Circuit also noted that the Board compared the marks in their entireties and further observe that: 1) the marks contained different letters and geometric shapes; 2) QuikTrip’s mark included a tilted chef’s hat; 3) phonetically, the marks do “not sound similar,” and the component Weigel’s adds an entirely different sound; and 4) the commercial impressions and connotations are different.

Accordingly, the Federal Circuit expressed that the Board’s finding of a lack of similarity was supported by substantial evidence.

- Factor 13 (Bad Faith as Another Probative Factor)

With respect to the thirteenth factor pertaining to asserted “bad faith” as being another probative factor, QuikTrip asserted that the evidence showed that Weigel acted in bad faith and that such bad faith further supported a finding of a likelihood of confusion.

However, the Federal Circuit explained that “an inference of ‘bad faith’ requires something more than mere knowledge of a prior similar mark.” Moreover, the Federal Circuit further explained that “[t[he only relevant intent is [an] intent to confuse.” The Federal Circuit noted that “[t]here is a considerable difference between an intent to copy and an intent to deceive.”

Accordingly, although the evidence showed that Weigel had taken photographs of QuikTrip’s stores and examined QuikTrip’s marketing materials, the Federal Circuit expressed that there was not an intent to deceive. In particular, the Federal Circuit emphasized that Weigel’s “willingness to alter its mark several times in order to prevent customer confusion [in response to QuikTrip’s cease-and-desist demands] negates any inference of bad faith.”

Accordingly, the Federal Circuit affirmed the decision of the Board.

Takeaways

- In evaluating similarities between trademarks for the determination of potential likelihood of confusion, although the evaluation is based on the marks in their entireties, different portions of the marks may be afforded different weight depending on circumstances. Accordingly, it is important to identify portions of the mark that are more distinctive in contrast to portions of the mark that may be descriptive or suggestive or commonly used in other marks.

- Although “bad faith” can help support a conclusion of a likelihood of confusion, it is important to keep in mind that “bad faith” does not merely require an “intent to copy,” but requires an “intent to deceive.”

- In the event that a trademark owner demands an alleged infringer cease-and-desist use of a mark, if the accused infringer substantially modifies its trademark in an effort to prevent customer confusion, according to the Federal Circuit, such action would “negate any inference of bad faith.” Accordingly, in order to help avoid any inference of bad faith, in response to a cease-and-desist demand, an accused infringer can help to avoid such an inference by modifying its trademark.

Tags: “DuPont Factors” Test > Likelihood of Confusion under 15 U.S.C. § 1052(d) > Similarity of Marks > Trademark

District court’s construction of a toothbrush claim gets flossed

| January 14, 2021

Maxill Inc. v. Loops, LLC (non-precedential)

December 31, 2020

Before Moore, Bryson, and Chen (Opinion by Chen).

Summary

Construing a claim reciting an assembly of identifiably separate components, the Federal Circuit determines that a limitation associated with a claimed component pertains to the component before it is combined with the other components. The lower court’s summary judgment of non-infringement, based on a claim construction requiring assembly, is reversed.

Details

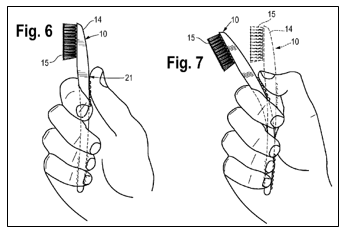

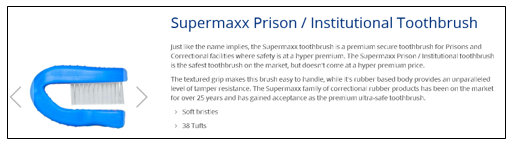

Loops, LLC and Loops Flexbrush, LLC (“Loops”) own U.S. Patent No. 8,448,285. The 285 patent is directed to a flexible toothbrush that is safe for distribution in correctional and mental health facilities. The toothbrush being made of flexible elastomers is less likely to be fashioned into a shiv.

Claim 1 of the 285 patent is representative and is reproduced below:

A toothbrush, comprising:

an elongated body being flexible throughout the elongated body and comprising a first material and having a head portion and a handle portion;

a head comprising a second material, wherein the head is disposed in and molded to the head portion of the elongated body; and

a plurality of bristles extending from the head forming a bristle brush,

wherein the first material is less rigid than the second material.

Maxill, Inc. makes “Supermaxx Prison/Institutional” toothbrushes that have a rubber-based, flexible body.

Loops and Maxill have for years been embroiled in patent infringement litigation, both in the U.S. and abroad, over flexible toothbrushes. This appeal arose out of a district court declaratory judgment action initiated by Maxill, who sought declaratory judgment of non-infringement and invalidity of the 285 patent.

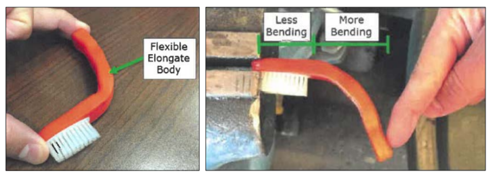

During the district court proceeding, Loops moved for summary judgment of infringement. In their opposition, Maxill argued that whereas the “flexible throughout” limitation in the 285 patent claims required that the body of the toothbrush be flexible from one end to the other, only the handle portion of the body of the Supermaxx toothbrush was flexible. The head portion of the toothbrush body, including the head, did not bend.

The district court agreed with Maxill, finding that Maxill’s Supermaxx toothbrush did not satisfy the “flexible throughout” limitation because the head portion of the toothbrush body, combined with the head, was rigid and unbendable. The district court then took the rare step of sua sponte granting Maxill summary judgment of non-infringement.

Loops appealed.

The main issue on appeal is the proper construction of the “flexible throughout” limitation. The question, however, is not simply whether the claim limitation requires that the body be flexible from one end to the other, but rather, whether the body must be flexible from one end to the other once assembled with the head.

As noted above, claim 1 of the 285 patent requires “an elongated body being flexible throughout the elongated body…and having a head portion and a handle portion”, and “a head…is disposed in and molded to the head portion of the elongated body”.

Does the “flexible throughout” limitation apply to the elongated body when it is combined with the head (i.e., post-assembly)? In that case, the district court was correct and Maxill’s Supermaxx toothbrush would not infringe the 285 patent.

Or does the “flexible throughout” limitation apply to the elongated body alone (i.e., pre-assembly)? In that case, the district court was wrong and Maxill’s Supermaxx toothbrush would be potentially infringing.

The Federal Circuit disagrees with the district court, determining that the “flexible throughout” limitation pertains to the elongated body alone and does not extend to the head even when the head is molded to the elongated body.

The Federal Circuit first looks at the claims, finding that the claims do not describe the head “as being a part of the elongated body; rather, the head…is identified in the claim as a separate element from the elongated body”.

Even though the claims require that the head be “disposed in and molded to” the elongated body, this recitation “does not meant that the head loses its identity as a separately identifiable component of the claimed toothbrush and somehow merges into becoming a part of the elongated body”,

The Federal Circuit then looks at the specification, finding that the specification consistently describes the head and elongated body as separate components.

Finally, the Federal Circuit finds that the prosecution history does not contain any “disclaimer requiring that the head be considered in evaluating the flexibility of the elongated body”.

The Federal Circuit is also bothered by the district court’s sua sponte summary judgment of non-infringement. This sua sponte action, says the Federal Circuit, deprived Loop of a full and fair opportunity to respond to Maxill’s non-infringement positions.

This case is interesting because the patentee seems to have accomplished a lot with (intentionally?) imprecise claim drafting. While the specification describes that the elongated body, as a standalone component, is fully flexible, there is no description that once combined with the head, the head portion of the elongated body remains flexible. But if the claims are construed the way the Federal Circuit has, written description or enablement is not an issue. And during prosecution, the patentee was able to distinguish over prior art teaching partially flexible toothbrush handles by arguing that the claimed elongated body was flexible throughout, but also distinguish over prior art disclosing toothbrushes with fully flexible handles and removable heads by arguing that the “permanent disposition of the head in the head portion is paramount in providing a fully flexible toothbrush while also providing the rigidity required in the head to effectively brush teeth”.

Takeaway

- Claim elements tend to be construed as identifiably separate components in the absence of claim language or descriptions in the specification indicating that the components are formed as a unitary whole. Take care when amending claims to add features that may exist only when the components are assembled or disassembled.

ALL PATENTABILITY ARGUMENTS SHOULD BE PRESENTED TO THE PTAB PRIOR TO AN APPEAL TO THE CAFC

| January 6, 2021

In Re: Google Technology holdings LLC

November 13, 2020

Chen (author), Taranto, and Stoll

Summary:

The Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s final decision that claims of Google’s patent application are unpatentable as obvious. The Federal Circuit found that since Google did not present its claim construction arguments before the PTAB in the first instance, Google forfeited these arguments and could not present again before the CAFC. The CAFC did not find any exceptional circumstances justifying considering these arguments before the CAFC.

Details:

Google Technology Holdings LLC (“Google”) appeals from the decision of the PTAB, where the PTAB affirmed the examiner’s final rejection of claims 1-9, 11, 14-17, 19, and 20 of the U.S. Patent Application No. 15/179,765 (‘765 application) under §103.

The ‘765 application is directed to “distributed caching for video-on-demand systems, and in particular to a method and apparatus for transferring content within such video-on-demand systems.” This application discloses a solution for how to determine streaming content to set-top boxes (STBs) and where to store the content among various content servers (video home offices (VHOs) or video server office (VSO)).

Claims 1 and 2 are representative claims of the ‘765 application and reproduced as follows:

1. A method comprising:

receiving, by a processing apparatus at a first content source, a request for content;

in response to receiving the request, determining that the content is not available from the first content source;

in response to determining that the content is not available from the first content source, determining that a second content source cost associated with retrieving the content from a second content source is less than a third content source cost associated with retrieving the content from a third content source, wherein the second content source cost is determined based on a network impact to fetch the content from the second content source to the first content source, . . .

2. The method of claim 1, further comprising:

determining that there is not sufficient memory to cache the content at the first content source; and

selecting one or more items to evict from a cache at the first content source to make available sufficient memory for the content, wherein the selection of the items to evict minimizes a network penalty associated with the eviction of the items, wherein the network penalty is based on sizes of the content and the items, and numbers of requests expected to be received for the content and the items.

Independent claim 1 recites a method of responding to requests to stream contents to STBs from content servers based on a cost of a network impact of fetching the content from the various content servers. Claim 2 recites a method of determining at which particular server(s) to store the content based on a network penalty.

During prosecution of the ‘765 application, the examiner rejected claim 1 in view of the Costa and Scholl references. The examiner rejected claim 2 in view of the Costa, Scholl, Allegrezza, and Ryu references.

PTAB

Google appealed the final rejection to the PTAB. Google argued that the cited references do not teach or suggest the claimed limitations (by “largely quoting the claim language and references” and “relying on block quotes from the claim language and the references”).

However, the PTAB affirmed the examiner’s obviousness rejections.

With regard to independent claim 1, the PTAB noted that because Google failed to cite a definition of “cost” or “network impact” in the specification that would preclude the examiner’s broad interpretation, the PTAB agrees with the examiner’s rejection that the combination of the cited references teaches or suggests the claimed limitation of independent claim 1.

With regard to claim 2, the PTAB noted that Google’s response were “conclusory,” and that Google “failed to rebut the collective teachings and suggestions of the applied references.” Instead, the PTAB argued that Google’s arguments focused merely on the shortcomings in the teachings of the cited references individually. Therefore, the PTAB agreed with the examiner.

Google did not introduce any construction of the term “network penalty” before the PTAB.

CAFC

First of all, the CAFC noted that “waiver is different from forfeiture.” United States v. Olano, 507 U.S. 725, 733 (1993). The CAFC noted that “whereas forfeiture is the failure to make the timely assertion of a right, waiver is the ‘intentional relinquishment or abandonment of a known right.’” Id. (quoting Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458, 464 (1938)).

Google argued to the CAFC that “[T]he Board err[ed] when it construed the claim terms ‘cost associated with retrieving the content’ and ‘network penalty’ in contradiction to their explicit definitions in the specification.” Therefore, Google argued that since the PTAB relied on the incorrect constructions of these two terms, the PTAB decision was not correct.

However, the CAFC noted that Google did not present these arguments to the PTAB. In other words, the CAFC noted that Google forfeited these arguments.

Google also argued to the CAFC that the CAFC should exercise its discretion to hear its forfeited arguments on appeal because (1) the PTAB sua sponte construed the term “cost”; and (2) the claim construction issue of “network penalty” is one of law fully briefed before the CAFC.

However, the CAFC noted that both arguments are not persuasive. The CAFC argued that Google did not provide any reasonable explanation as to why it never argued to the examiner during the prosecution or later to the PTAB. Also, the CAFC argued that since Google forfeited its argument for “network penalty” before the PTAB, Google’s second argument is not persuasive as well.

Therefore, the PTAB affirmed the PTAB’s decision upholding the rejection of the claims of the ‘765 application.

Takeaway:

- Applicant should make sure to present all arguments before the PTAB prior to an appeal to the CAFC.

- Factual issues v. legal issues: the CAFC applies significant deference to the PTAB on the factual issues (i.e., what the cited references teach and whether those teachings meet the claim limitations); the CAFC reviews legal questions without deference.

- There are benefits for an appeal to the CAFC: if the claim rejections are reversed, the prosecution is terminated, and the appealed claims are allowed without narrowing the claims (MPEP 1216.01 I.B and I.D).

New evidence submitted with a reply in IPR institution proceedings

| December 30, 2020

VidStream LLC v. Twitter, Inc.

November 25, 2020

Newman, O’Malley, and Taranto. Court opinion by Newman.

Summary

On appeals from the United States Patent and Trademark Office in IPR arising from two petitions filed by Twitter, the Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s ruling that Bradford is prior art (printed publication) against the ’997 patent where the priority date of the ’997 patent is May 9, 2012 and a page of the copy of Bradford cited in Twitter’s petitions stated, in relevant parts, “Copyright © 2011 by Anselm Bradford and Paul Haine” and “Made in the USA Middletown, DE 13 December 2015.” The Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s admission of new evidence regarding Bradford submitted by Twitter in reply (not included in petitions). The Federal Circuit also affirmed the Board’s rulings of unpatentability of claims 1– 35 of the ’997 patent over Bradford and other prior art references, in the two IPR decisions on appeal.

Details

I. background

U.S. Patent No. 9,083,997 (“the ’997 patent”), assigned to VidStream LLC, is directed to “Recording and Publishing Content on Social Media Websites.” The priority date of the ’997 patent is May 9, 2012.

Twitter filed two petitions for inter partes review (“IPR”), with method claims 1–19 of the ’997 patent in one petition, and medium and system claims 20–35 of the ’997 patent in the other petition. Twitter cited Bradford as the primary reference for both petitions, combined with other references.

With the petitions, Twitter filed copies of several pages of the Bradford book, and explained their relevance to the ’997 claims. Twitter also filed a Bradford copyright page that contains the following legend:

Copyright © 2011 by Anselm Bradford and Paul Haine

ISBN-13 (pbk): 978-1-4302-3861-4

ISBN-13 (electronic): 978-1-4302-3862-1

A page of the copy of Bradford cited in Twitter’s petitions also states:

Made in the USA

Middletown, DE

13 December 2015

VidStream, in its patent owner’s response, argued that Bradford is not an available reference because it was published December 13, 2015.

Twitter filed replies with additional documents, including (i) a copy of Bradford that was obtained from the Library of Congress, marked “Copyright © 2011” (this copy did not contain the “Made in the USA Middletown, DE 13 December 2015” legend); and (ii) a copy of Bradford’s Certificate of Registration that was obtained from the Copyright Office and contains following statements:

Effective date of registration: January 18, 2012

Date of 1st Publication: November 8, 2011

“This Certificate issued under the seal of the Copyright Office in accordance with title 17, United States Code, attests that registration has been made for the work identified below. The information on this certificate has been made a part of the Copyright Office records.”

Twitter also filed following declarations:

The Declaration of “an expert on library cataloging and classification,” Dr. Ingrid Hsieh-Yee, who declared that Bradford was available at the Library of Congress in 2011 with citing a Machine-Readable Cataloging (“MARC”) record that was created on August 25, 2011 by the book vendor, Baker & Taylor Incorporated Technical Services & Product Development, adopted by George Mason University, and modified by the Library of Congress on December 4, 2011.

the Declaration of attorney Raghan Bajaj, who stated that he compared the pages from the copy of Bradford submitted with the petitions, and the pages from the Library of Congress copy of Bradford, and that they are identical.

Twitter further filed copies of archived webpages from the Internet Archive, showing the Bradford book listed on a publicly accessible website (http://www.html5mastery.com/) bearing the website date November 28, 2011, and website pages dated December 6, 2011 showing the Bradford book available for purchase from Amazon in both an electronic Kindle Edition and in paperback.

VidStream filed a sur-reply challenging the timeliness and the probative value of the supplemental information submitted by Twitter.

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB” or “Board”) instituted the IPR petitions, found that Bradford was an available reference, and held claims 1–35 unpatentable in light of Bradford in combination with other cited references. Regarding Bradford, the Board discussed all the materials that were submitted, and found:

“Although no one piece of evidence definitively establishes Bradford’s public accessibility prior to May 9, 2012, we find that the evidence, viewed as a whole, sufficiently does so. In particular, we find the following evidence supports this finding: (1) Bradford’s front matter, including its copyright date and indicia that it was published by an established publisher (Exs. 1010, 1042, 2004); (2) the copyright registration for Bradford (Exs. 1015, 1041); (3) the archived Amazon webpage showing Bradford could be purchased on that website in December 2011 (Ex. 1016); and (4) Dr. Hsieh-Yee’s testimony showing creation and modification of MARC records for Bradford in 2011.”

VidStream timely appealed.

II. The Federal Circuit

The Federal Circuit unanimously affirmed all aspects of the Board’s holdings including Bradford being prior art (printed publication).

The critical issue on this appeal is whether Bradford was made available to the public before May 9, 2012, the priority date of the ’997 patent.

Admissibility of Evidence – PTAB Rules and Procedure

VidStream argued that Twitter was required to include with its petitions all the evidence on which it relies because the PTO’s Trial Guide for inter partes review requires that “[P]etitioner’s case-in-chief” must be made in the petition, and “Petitioner may not submit new evidence or argument in reply that it could have presented earlier.” Trial Practice Guide Update, United States Patent and Trademark Office 14–15 (Aug. 2018), https://www.uspto.gov/sites/de- fault/files/documents/2018_Revised_Trial_Practice_Guide. pdf.

Twitter responded that the information filed with its replies was appropriate in view of VidStream’s challenge to Bradford’s publication date, and that this practice is permitted by the PTAB rules and by precedent, which states: “[T]he petitioner in an inter partes review proceeding may introduce new evidence after the petition stage if the evidence is a legitimate reply to evidence introduced by the patent owner, or if it is used to document the knowledge that skilled artisans would bring to bear in reading the prior art identified as producing obviousness.” Anacor Pharm., Inc. v. Iancu, 889 F.3d 1372, 1380–81 (Fed. Cir. 2018).

The Federal Circuit sided with Twitter, concluding that the Board acted appropriately, for the Board permitted both sides to provide evidence concerning the reference date of the Bradford book, in pursuit of the correct answer.

The Bradford Publication Date

VidStream argued that, even if Twitter’s evidence submitted in reply were considered, the Board did not link the 2015 copy of Bradford with the evidence purporting to show publication in 2011, i.e., the date of copyright registration, the archival dates for the Amazon and other webpages, and the date the MARC records were created. VidStream argued that the Board did not “scrutiniz[e] whether those documents actually demonstrated that any version of Bradford was publicly accessible at that time.” VidStream states that Twitter did not meet its burden of showing that Bradford was accessible prior art.

Twitter responded that that the evidence established the identity of the pages of Bradford filed with the petitions and the pages from the copy of Bradford in the Library of Congress. Twitter explains that the copy “made” on December 13, 2015 was a reprint, for the 2015 copy has the same ISBN as the Library of Congress copy, as is consistent with a reprint, not a new edition.

After citing arguments of both parties, the Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s ruling that Bradford is prior art against the ’997 patent because “[t]he evidence well supports the Board’s finding that Bradford was published and publicly accessible before the ’997 patent’s 2012 priority date.” There is no more explanation than this for the affirmance.

Obviousness Based on Bradford

The Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s rulings of unpatentability of claims 1– 35 of the ’997 patent, in the two IPR decisions on appeal because VidStream did not challenge the Board’s decision of obviousness if Bradford is available as a reference.

Takeaway

· Although all relevant evidence should be submitted with an IPR petition, new evidence submitted with a reply may have chance to be admitted if the new evidence is a legitimate reply to the evidence introduced by a patent owner, or if it is used to document the knowledge that skilled artisans would bring to bear in reading the prior art identified as producing obviousness.

Box designs for dispensing wires and cables affirmed as functional, not registrable as trade dresses

| December 23, 2020

In re: Reelex Packaging Solution, Inc. (nonprecedential)

November 5, 2020

Moore, O’Malley, Taranto (Opinion by O’Malley)

Summary

In a nonprecedential opinion, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the “CAFC”), affirmed the decision of the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (the “TTAB”), upholding the examining attorney’s refusal to register two box designs for electric cables and wire as trade dresses on grounds that the designs are functional.

Details

Reelex filed two trade dress applications for coils of cables and wire in International Class 9.

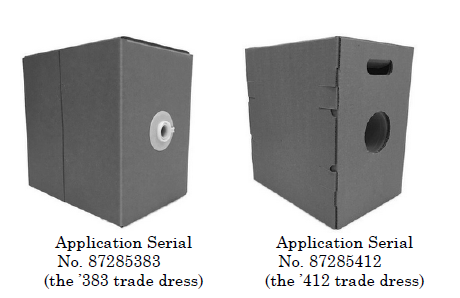

The trade dress of Application Serial No. 87285383 (the ‘383 trade dress) is described as follows:

The mark consists of trade dress for a coil of cable or wire, the trade dress comprising a box having six sides, four sides being rectangular and two sides being substantially square, the substantially square sides both having a length of between 12 and 14 inches, the rectangular sides each having a length of between 12 and 14 inches and a width of between 7.5 and 9 inches and a ratio of width to length of between 60% and 70%, one, and only one rectangular side having a circular hole of between 0.75 and 1.00 inches in the exact middle of the side with a tube extending through the hole and through which the coil is dispensed from the package, the tube having an outer end extending beyond an outer surface of the rectangular side, and a collar extending around the outer end of the tube on the outer surface of the rectangular side of the package, and one square side having a line folding assembly bisecting the square side.

The trade dress of Application Serial No. 87285412 (the ‘412 trade dress) is described as follows:

The mark consists of trade dress for a coil of cable or wire, the trade dress comprising a box having six sides, four sides being rectangular and two sides being substantially square, the substantially square sides both having a length of between 13 and 21 inches, the rectangular sides each having a length of the same length of the square sides and a width of between 57% and 72% of the size of the length, one, and only one rectangular side having a circular hole of 4.00 inches in the exact middle of the side with a tube extending in the hole and through which the coil is dispensed from the package, one square side having a tongue and a groove at an edge adjacent the rectangular side having the circular opening, and the rectangular side having the circular opening having a tongue and a groove with the tongue of each respective side extending into the groove of each respective side at a corner therebetween.

The examining attorney refused the applications, finding the design of the boxes as being functional and non-distinctive. Further, the examining attorney found that the designs do not function as trademarks to indicate the source of the goods. On an appeal to the TTAB, the Board affirmed the examining attorney to register on the grounds of functionality and distinctiveness. Regarding functionality, the Board found that the features of these boxes – the rectangular shape, built-in handle for the ‘412 design, and dimensions of the boxes and the size and placement of the payout tubes and payout holes, are “clearly dictated by utilitarian concerns.” The Board also found that the payout holes and their position on the boxes allowed users easy access and twist-free dispensing.

While the Board found above to be sufficient evidence to uphold the functionality refusal, the Board went further to considered the following four factors from In re Morton-Norwich Products, Inc., 671 F.2d 1332 (CCPA 1982):

(1) the existence of a utility patent that discloses the utilitarian advantages of the design sought to be registered;

(2) advertising by the applicant that touts the utilitarian advantages of the design;

(3) facts pertaining to the availability of alternative designs; and

(4) facts pertaining to whether the design results from a comparatively simple or inexpensive method of manufacture.

- Existence of a utility patent

With regard to the first factor, Reelex submitted five utility patents relating to the applied-for marks:

- U.S. Patent No. 5,810,272 for a Snap-On Tube and Locking Collar for Guiding Filamentary Material Through a Wall Panel of a Container Containing Wound Filamentary Material;

- U.S. Patent No. 6,086,012 for Combined Fiber Containers and Payout Tube and Plastic Payout Tubes;

- U.S. Patent No. 6,341,741 for Molded Fiber and Plastic Tubes;

- U.S. Patent No. 4,160,533 for a Container with Octagonal Insert and Corner Payout; and

- U.S. Patent No. 7,156,334 for a Pay-Out Tube.

The Board found that the patents revealed several benefits of various features of the two boxes, weighing in favor of finding the designs of the two boxes to be functional.

- Advertising by the applicant

The second factor also weighed in favor of finding functionality. Reelex’s advertising materials repeatedly touted the utilitarian advantages of the boxes, which allow for dispensing of cable or wire without kinking or tangling. The boxes’ recyclability, shipping, and storage advantages were also being touted. The evidence weighed in favor of finding functionality.

- Alternative designs

The Board explained that in cases where patents and advertising demonstrate functionality of designs, there is no need to consider the availability of alternative designs. Nevertheless, the Board considered evidence submitted by Reelex, and found the evidence to be speculative and contradictory to its own advertising and patents. Therefore, the Board found the evidence to be unpersuasive.

- Comparatively simple or inexpensive method of manufacture

Regarding this last factor, the Board found no evidence of record regarding the cost or complexity of manufacturing the trade dress.

Considering and analyzing the case using the Morton-Norwich factors, the Board found the design of Reelex’s trade dress to be “essential to the use or purpose of the device” as used for “electric cable and wires.”

On appeal, Reelex argued that evidence shows that the trade dresses at issue “provide no real utilitarian advantage to the user.” In addition, Reelex argued that the Board erred in failing to consider evidence of alternative designs.

The CAFC found there to be substantial evidence to support the Board’s finding of multiple useful features in the design of the boxes, and these features were properly analyzed by the Board as a whole and in combination, and the Board did not improperly dissect the designs of the two trade dresses into discrete design features. The CAFC also found there to be sufficient evidence supporting the Board’s finding of functionality using the Morton-Norwich factors.

As to whether the Board considered Reelex’s evidence of alternative designs, the Board expressly considered Reelex’s evidence of alternative designs, and found the evidence to be both speculative and contradictory. For example, although the declaration submitted by Reelex stated that the shape of the package, as well as the shape, size, and location of the payout hole, were merely ornamental, Reelex’s utility patents repeatedly refer to the utilitarian advantages of the two box designs.

Therefore, the CAFC affirmed the decision of the Board, upholding the examining attorney’s refusal to register the two trade dress applications because they are functional.

Takeaway

- Functional designs cannot be registered as a trade dress. If a utility patent exists for a design, it is likely that the same design cannot also be protected as a trade dress.

- Note that there is an overlap in design patent and trade dress. Existence of a design patent does not preclude an applicant from filing a trademark application for the same design.

Printed Matter Challenge to Patent Eligiblity

| December 11, 2020

C R Bard Inc. v. AngioDynamics Inc.

November 10, 2020

Opinion by: Reyna, Schall, and Stoll (November 10, 2020).

Summary:

A vascular access port patent recited “identifiers” that were not given patentable weight under the printed matter doctrine. Printed matter constitutes an abstract idea under Alice step 1. Nevertheless, even though printed matter was not given any patentable weight and the claim was directed to printed matter under Alice step 1, the claims were found eligible under Alice step 2.

Background:

Bard sued AngioDynamics in the District of Delaware for infringing U.S. Patent Nos. 8,475,417, 8,545,460, and 8,805,478. One representative claim is claim 1 of the ‘417 patent:

An assembly for identifying a power injectable vascular access port, comprising:

a vascular access port comprising a body defining a cavity, a septum, and an outlet in communication with the cavity;

a first identifiable feature incorporated into the access port perceivable following subcutaneous implantation of the access port, the first feature identifying the access port as suitable for flowing fluid at a fluid flow rate of at least 1 milliliter per second through the access port;

a second identifiable feature incorporated into the access port perceivable following subcutaneous implantation of the access port, the second feature identifying the access port as suitable for accommodating a pressure within the cavity of at least 35 psi, wherein one of the first and second features is a radiographic marker perceivable via x-ray; and

a third identifiable feature separated from the subcutaneously implanted access port, the third feature confirming that the implanted access port is both suitable for flowing fluid at a rate of at least 1 milliliter per second through the access port and for accommodating a pressure within the cavity of at least 35 psi.

Vascular access ports are implanted underneath a patient’s skin to allow injection of fluid into the patient’s veins on a regular basis without needing to start a new intravenous line every time. Certain procedures, such as computed tomography (CT) imaging, required high pressure and high flow rate injections through such ports. However, traditional vascular access ports were used for low pressure and flow rates, and sometimes ruptured under high pressures and flow rates. FDA approval was eventually required for vascular access ports that were structurally suitable for power injections under high pressures and flow rates. To distinguish between FDA approved power injection ports versus traditional ports, Bard used the claimed radiographic marker (e.g., “CT” etched in titanium foil on the device) on its FDA approved power injection ports that could be detected during an x-ray scan typically performed at the start of a CT procedure. Additional identification mechanisms included small bumps that were palpable through the skin, and labeling on device packaging and items that can be carried by the patient (e.g., keychain, wristband, sticker). AngioDynamics also received FDA approval for its own power injection vascular access ports including a scalloped shaped identifier and a radiographic “CT” marker.

AngioDynamics raised ineligibility under §101 using the printed matter doctrine to nix patentable weight for the claimed identifiers in its motion to dismiss the complaint, its summary judgment motion, and later during the trial on an oral JMOL motion. In advance of the trial, the district court requested a report and recommendation from a magistrate judge regarding whether “radiographic letters” and “visually perceptible information” limitations in the claims were entitled patentable weight under the printed matter doctrine, as part of claim construction. The district court judge adopted the magistrate judge’s recommendations on the printed matter and ultimately granted AngioDynamic’s JMOL motion for ineligiblity.

The Printed Matter Doctrine:

This decision summarized the printed matter doctrine as follows:

- “printed matter” is not patentable subject matter

- the printed matter doctrine prohibits patenting printed matter unless it is “functionally related” to its “substrate,” which includes the structural elements of the claim

- while this doctrine started out with literally “printed” material, it has evolved over time to encompass “conveyance of information using any medium,” and “any information claimed for its communicative content.”

- “In evaluating the existence of a functional relationship, we have considered whether the printed matter merely informs people of the claimed information, or whether it instead interacts with the other elements of the claim to create a new functionality in a claimed device or to cause a specific action in a claimed process.”

Here, there is no dispute that the claims include printed matter (markers) “identifying” or “confirming” suitability of the port for high pressure or high flow rate. These markers inform people of the claimed information – suitability for high pressure or high flow rate.

Bard asserted that the markers provided a new functionality for the port to be “self-identifying.” This reasoning was rejected because mere “self-identification” being new functionality “would eviscerate our established case law that ‘simply adding new instructions to a known product’ does not create a functional relationship.” For instance, marking of meat and wooden boards with information concerning the product does not create a functional relationship between the printed information and the substrate.

Bard asserted that the printed matter is functionally related to the power injection step of the method claims because medical providers perform the power injection “based on” the markers. This reasoning was also rejected because the claims did not recite any such causal relationship.

Accordingly, the Federal Circuit held that the markers and the information conveyed by the markers, i.e., that the ports are suitable for power injection, is printed matter not entitled to patentable weight.

Nevertheless, despite the holding about printed matter not given patentable weight, the Federal Circuit still found the claims to be patent eligible under Alice step 2.

Before getting to Alice step 2, the Federal Circuit equates printed matter to an abstract idea, citing to an eighty year old decision “where the printed matter, is the sole feature of alleged novelty, it does not come within the purview of the statute, as it is merely an abstract idea, and, as such, not patentable.” The court further equates this to post-Alice decisions (Two-Way Media, Elec. Pwr Grp, Digitech) recognizing that “the mere conveyance of information that does not improve the functioning of the claimed technology is not patent eligible subject matter. under §101.” “We therefore hold that a claim may be found patent ineligible under §101 on the grounds that it is directed solely to non-functional printed matter and the claim contains no additional inventive concept.”

However, with regard to Alice step 2’s inventive concept, the court viewed “the focus of the claimed advance is not solely on the content of the information conveyed, but also on the means by which that information is conveyed” (i.e., via the radiographic marker). Bard admitted that use of radiographically identifiable markings on implantable medical devices was known in the prior art. Nevertheless, “[e]ven if the prior art asserted by AngioDynamics demonstrated that it would have been obvious to combine radiographic marking with the other claim elements, that evidence does not establish that radiographic marking was routine and conventional under Alice step two.” “AngioDynamics’ evidence is not sufficient to establish as a matter of law, at Alice step two, that the use of a radiographic marker, in the ‘ordered combination’ of elements claimed, was not an inventive concept.” Even with regard to the corresponding method claim, “while the FDA directed medical providers to verify a port’s suitability for power injection before using a port for that purpose, it did not require doing so via imaging of a radiographic marker…[t]here is no evidence in the record that such a step was routinely conducted in the prior art.”

Takeaways:

- The printed matter doctrine not only precludes patentable weight for §§102 and 103 inquiries, but also raises abstract idea issues under Alice step 1.

- This case also reminds us of the eligibility hurdles for data processing inventions, with Two-Way Media “concluding that claims directed to the sending and receiving of information were unpatentable as abstract where the steps did not lead to any ‘improvement in the functioning of the system;’” Elec. Pwr Grp “holding that claims directed to ‘a process of gathering and analyzing information of a specified content, then displaying the results, and not any particular assertedly inventive technology for performing those functions’ are directed to an abstract idea;” and Digitech stating that “data in its ethereal, non-physical form is simply information that does not fall under any of the categories of eligible subject matter under section 101.”

- For Alice step 2, this case exemplifies the high bar for establishing “routine and conventional.” Here, the patentee’s admission that radiographic marking on implanted medical devices is known in the prior art was not enough to establish “routine and conventional.” Even prior art that demonstrates the obviousness of combining radiographic marking with the other claim elements was also not enough to establish “routine and conventional.”

- For Alice step 2, this case may exemplify the breadth of what constitutes an inventive concept in “an ordered combination.” The court does not specify exactly what the “ordered combination” was here. Perhaps, the “significantly more” (beyond the abstract idea of the printed matter) could simply be the combination of a radiographic marker and a port.

Dependent Claims Cannot Broaden an Independent Claim from Which They Depend

| December 4, 2020

Network-1 Technologies, Inc. v. Hewlett-Packard Company, Hewlett-Packard Enterprise Company

Before PROST, Chief Judge, NEWMAN and BRYSON, Circuit Judges.

Summary

The Federal Circuit reversed, in part, and affirmed, in part, the district court’s decision and ordered a new trial on infringement. Because the district court erred in construing one patent claim, the Federal Circuit concluded that the district court’s erroneous claim construction established prejudice towards Network-1. The Federal Circuit also affirmed the district court’s judgment that the dependent claims did not improperly broaden one of the asserted claims.

Background

Network-1 Technologies, Inc. (“Network-1”) owns U.S. Patent 6,218,930 (the ‘930 patent), entitled “Apparatus and Method for Remotely Powering Access Equipment over a 10/100 Switched Ethernet Network,” which sued Hewlett-Packard (“HP”) for infringement in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas. The jury found the patent not infringed and invalid. But the district court granted Network-1’s motion for judgment as a matter of law (“JMOL”) on validity following post-trial motions.

Network-1 appealed the district court’s final judgment that HP does not infringe the ’930 patent, arguing the district court erred in its claim construction on “low level current” and “main power source.” HP cross-appealed the district court’s estoppel determination in raising certain validity challenges under 35 U.S.C. § 315(e)(2) based on HP’s joinder to an inter partes review (“IPR”) before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“the Board”). Also, HP argued that Network-1 improperly broadened claim 6 of the ’930 patent by adding two dependent claims 15 and 16.

Discussion

The ’930 patent discloses an apparatus and methods for allowing electronic devices to automatically determine if remote equipment is capable of accepting remote power over Ethernet. On appeal, the arguments on the alleged infringement are drawn towards claim 6 as follows.

6. Method for remotely powering access equipment in a data network, comprising,

providing a data node adapted for data switching, an access device adapted for data transmission, at least one data signaling pair connected between the data node and the access device and arranged to transmit data therebetween, a main power source connected to supply power to the data node, and a secondary power source arranged to supply power from the data node via said data signaling pair to the access device,

delivering a low level current from said main power source to the access device over said data signaling pair,

sensing a voltage level on the data signaling pair in response to the low level current, and

controlling power supplied by said secondary power source to said access device in response to a preselected condition of said voltage level.

Network-1 argued that the district court erroneously construed the claim terms “low level current” and “main power source” in claim 6. About “low level current,” the district court imposed both an upper bound (the current level cannot be sufficient to sustain start up) … and a lower bound (the current level must be sufficient to begin startup). Network-1 admitted that the term “low level current” describes current that cannot “sustain start up” but disagreed with the district court’s construction that the current has a lower bound at a level sufficient to begin start up.

The Federal Circuit reviewed the arguments and made it clear that “[T]he claims themselves provide substantial guidance as to the meaning of particular claim terms” and “the specification is the single best guide to the meaning of a disputed term.” It has been pointed out that the claim phrase is not limited to the word “low,” and the claim construction analysis should not end just because one reference point has been identified. The Federal Circuit further explained that the claim phrase “low level current” does not preclude a lower bound by using the word “low.” Rather, in the same way the phrase should be construed to give meaning to the term “low,” the phrase must also be construed to give meaning to the term “current.” The term “current” necessarily requires some flow of electric charge because “[i]f there is no flow, there is no ‘current.’” Therefore, the Federal Circuit confirms that the district court correctly construed the phrase “low level current.”

However, the Federal Circuit held that the district court erred in its construction of “main power source” in the patent claims resulting in prejudice towards Network-1. The district court construed “main power source” as “a DC power source,” thereby excluding AC power sources from its construction. The Federal Circuit concluded that the correct construction of “main power source” includes both AC and DC power sources. Although HP argued that the erroneous claim construction was harmless and no accused product meets the claim limitation “delivering a low level current from said main power source,” the Federal Circuit confirmed that Network-1 has established that the claim construction prejudiced it because the evidence shows that HP relied on the district court’s erroneous construction for its argument. The district court’s erroneous claim construction of “main power source” is entitled Network-1 to a new trial on infringement.

On cross-appeal, HP argued that the district court erred in concluding that HP was statutorily estopped from raising certain invalidity. In this case, HP did not petition for IPR but relied on the joinder exception to the time bar under § 315(b). HP first filed a motion to join the Avaya IPR with a petition requesting review based on grounds not already instituted. The Board correctly denied HP’s first request but later granted HP’s second joinder request, which petitioned for only the two grounds already instituted. The Federal Circuit reasoned that “HP, however, was not estopped from raising other invalidity challenges against those claims because, as a joining party, HP could not have raised with its joinder any additional invalidity challenges.” A party is only estopped from challenging claims in the final written decision based on the grounds that it “raised or reasonably could have raised” during the inter partes review (IPR). Hence, the Federal Circuit ruled that HP was not statutorily estopped from challenging the asserted claims of the ’930 patent, which were not raised in the IPR and could not have reasonably been raised by HP.

Prior to reexamination, claim 6 of the ’930 patent was construed to require the “secondary power source” to be physically separate from the “main power source.” But during the reexamination, Network-1 added claims 15 and 16, which depended from claim 6 and respectively added the limitations that the secondary power source “is the same source of power” and “is the same physical device” as the main power source. HP argued that claim 6 and the other asserted claims are invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 305 because Network-1 improperly broadened claim 6 by adding claim 15 and 16 in the reexamination. However, the Federal Circuit does not agree that claim 6 is invalid for improper broadening based on the addition of claims 15 and 16. First, a patentee is not permitted to enlarge the scope of a patent claim during reexamination. The broadening inquiry involves two steps: (1) analyzing the scope of the claim prior to reexamination and (2) comparing it with the scope of the claim subsequent to reexamination. The Federal Circuit’s broadening inquiry begins and ends with claim 6. Because claim 6 was not itself amended, the scope of claim 6 was not changed as a result of the reexamination. Where the scope of claim 6 has not changed, there has not been improper claim broadening. Dependent claims cannot broaden an independent claim from which they depend. Accordingly, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s conclusion that claim 6 and the other asserted claims are not invalid due to improper claim broadening.

Takeaway

- A party is only estopped from challenging claims in the final written decision based on grounds that it “raised or reasonably could have raised” during the inter partes review (IPR).

- Dependent claims cannot broaden an independent claim from which they depend.

What Does It Mean To Be Human?

| November 26, 2020

Immunex Corp v. Sanofi-Aventis U.S. LLC

Prost, Reyna and Taranto.Opinion by Prost

October 13, 2020

Summary

This is a consolidated appeal from two Patent and Trademark Appeal Board (“Board”) decisions in Inter partes reviews (IPR) of US Patent No. 8,679,487 (‘487 patent) owned by Immunex. In the first IPR the Board invalidated all challenged claims. Immunex appealed the construction of the claim term “human antibodies.” In the other IPR, involving a subset of the same claims, the Board did not invalidate the patent for reason of inventorship. Sanofi appealed the Boards inventorship determination.

Briefly, the CAFC agreed with the Board’s claim construction and affirmed the invalidity decision. Since this left no claims valid, the CAFC dismissed Sanofi’s inventorship appeal.

The ’487 patent is directed to antibodies that bind to human interleukin-4 (IL-4) receptor. This appeal concerned what “human antibody” means in this patent. That is, in the context of this patent, must a human antibody be entirely human, or does it include partially human, for example humanized?

Amid infringement litigation, Sanofi filed three IPR’s against the ‘487 patent, two if which were instituted. In one final decision the Board concluded that the claims were unpatentable as obvious over two references, Hart and Schering-Plough. Hart describes a murine antibody that meet all the limitations of claim 1 except that it is fully murine, so not human at all. The Schering-Plough reference teaches humanizing murine antibodies.

In response, Immunex insisted that the Board had erred in construction of “human antibody” to include humanized antibodies.

After Appellate briefing was complete, Immunex filed with the PTO a terminal disclaimer of its patent. The PTO accepted it, and the patent expired May 26, 2020, just over two months prior to oral arguments. Immunex then filed a citation apprising the CAFC of (but not explaining the reason for) its terminal disclaimer and asking the court to change the applicable construction standard.

Specifically, in all newly filed IPRs, the Board now applies the Phillips district-court claim construction standard. However, when Sanofi filed its IPR, the Board applied this standard to expired patents only. To unexpired patents, it applied the Broadest Reasonable Interpretation (BRI) standard.

Immunex urged the CAFC to apply Phillips citing Wasica Finance GmbH v., Continental Automotive Systems, Inc., 853 F.3d 1272, 1279 (Fed. Cir. 2017) and In re CSB-System International 832 F. 3d 1335, as support. However, unlike here, the patents at issues in these cases had expired before the Board’s decision. The CAFC noted that it had applied the Phillips standard when a patent expired on appeal. Nonetheless, the CAFC clarified that in these cases the patent terms had expired as expected and not cut short by a litigant’s terminal disclaimer.

Accordingly, the CAFC affirmed it will review the Board’s claim construction under the BRI standard.

Initially, the CAFC turned to the intrinsic record, specifically, the claims, the specification, and the prosecution history.

The CAFC noted that the claims themselves were not helpful as the dependent claims provided no further guidance.

Next, the CAFC noted that while the specification gave no actually definition, the usage of “human” throughout the specification confirmed its breadth. Specifically, the specification contrasts “partially human’ with “fully human.” For instance, the specification states that “an antibody…include, but are not limited to, partially human…. fully human.” Thus, the specification makes it clear that “human antibody” is a broad category encompassing both “fully” and “partially.”

Immunex insisted that the Board undervalued the prosecution history. While the CAFC agreed, it concluded the prosecution history supported the Board’ construction.

First, they noted that Immunex had used the term “fully human” and “human” in the same claim of another of its patents in the same family. Next, claim 1 as originally presented merely stated “an isolated antibody” and “human” were added during prosecution.

As a result, a dependent claim which recited ‘a human, partially human, humanized or chimeric antibody’ was cancelled. Immunex suggested that the amendment “surrendered” the partially human embodiment. The CAFC disagreed.

The Board noted that “human” was not added to overcome an anticipating reference that disclosed ‘nonhuman.’ The CAFC also noted that the claim language does not require the exclusion of partially human embodiments. Thus, the CAFC held that nothing indicates that “human” was added to limit the scope to fully human.

The CAFC noted that in a post-amendment office action, the Examiner expressly wrote that the amended “human” antibodies encompassed “humanized” antibodies and that Immunex had made no effort to correct this understanding.

Next, the CAFC addressed the role of extrinsic evidence. Immunex argued that the Board had failed to establish how a person of ordinary skill in the art would have understood the term. Immunex had provided expert testimony to argue that “human antibody” would have been limited to “fully human.”

The CAFC held that while it is true that they seek the meaning of a claim term from the perspective of a person of ordinary skill in the art, the key is how that person would have understood the term in view of the specification. That, while extrinsic evidence may illuminate a well-understood technical meaning, that does not mean that litigants can introduce ambiguity in a way that disregards usage in the patent itself.

Here, the extrinsic evidence provided conflicts the intrinsic evidence. Priority is given to the intrinsic evidence.

Lastly, the CAFC discussed the Boards’ departure from an earlier court’s claim construction. That is, in the litigation that prompted this IPR, a district court construed “human” to mean “fully human” only, under the narrower Phillips-based construction. However, the CAFC reiterated that the Board “is not generally bound by a previous judicial construction of a claim term.”

Thus, to conclude, the CAFC affirmed the Board’s claim construction under the BRI standard, and thus its invalidity judgment based thereon.

Take-away

- Claim drafting – words matter

- The importance of dependent claims

- Be mindful of amendments made during prosecution that are not done for the purpose of overcoming prior art.

- In claim construction, intrinsic evidence has priority over extrinsic evidence when they conflict.

- Be mindful of comments made by the Examiner during prosecution in an action (office action, notice of allowance, etc.,) regarding interpretation of the claims.