Vavada Casino Polska – kasyno online 2026

| February 18, 2026

Vavada Casino Polska – kasyno online 2026 – recenzja, bonusy, wskazówki

Vavada Casino to popularna platforma hazardowa dostępna dla graczy w Polsce, gdzie znaleźć możesz nie tylko bogaty wybór gier czy atrakcyjne bonusy, ale również wygodne metody płatności oraz intuicyjny interfejs. Przekonaj się,

jakie są najważniejsze zalety kasyna online Vavada dla polskich graczy. Sięgnij po bonus powitalny, zgarniaj promocje dla stałych klientów i odkryj tysiące automatów od topowych deweloperów. Dołącz do gry już dziś – załóż konto

i rozpocznij przygodę z najlepszym kasynem internetowym!

Vavada Casino recenzja – najważniejsze informacje

Z roku na rok przybywa w kasynie zarejestrowanych graczy, którzy poszukują tutaj unikalnych rozwiązań w dziedzinie hazardu. Kasyno online cieszy się rosnącym zainteresowaniem wśród entuzjastów slotów online, gier na żywo, a także

tradycyjnych rozgrywek stołowych i karcianych. Trzeba przy tym podkreślić, że kasyno jest całkowicie legalne, gdyż prowadzi działalność na podstawie posiadanej przez operatora licencji kasynowej.

Zanim przejdziesz do rejestracji, wpłaty depozytu i wyboru gry, poznaj kasyno z bliska. Najważniejsze informacje zebraliśmy dla Ciebie w poniższej tabelce:

Kasyno Vavada Poland – status na lokalnym rynku

Właściciel kasyna internetowego dokłada wszelkich starań, aby uprzyjemnić doświadczenie polskiego użytkownika podczas gry w serwisie. Dlatego też cała platforma hazardowa została przetłumaczona na język polski, a gracze mogą realizować

płatności przy użyciu polskiej waluty. Na uwagę zasługuje również dostępność witryny Vavada PL, z którą bez trudu połączyć się mogą gracze pochodzący z Polski.

Vavada Casino opinie wśród rodzimych entuzjastów hazardu online ma niezwykle pozytywne. Rośnie też liczba zarejestrowanych graczy, którzy cenią sobie fachowe podejście operatora do tematu lokalizacji językowej. Jeśli szukasz zatem godnego

zaufania kasyna sieciowego, koniecznie zajrzyj na oficjalną stronę i zacznij grać już dziś.

Licencje i bezpieczeństwo – czy Vavada Polska to legalne kasyno?

Właścicielem kasyna internetowego jest spółka Vavada B.V., która prowadzi legalną działalność hazardową na podstawie aktywnej licencji. Certyfikat ten został przyznany przez organ regulujący hazard online z Curacao. Numer dokumentu

to 8048/JAZ2017-035. W praktyce posiadanie takiej licencji sprawia, że platforma działa zgodnie z obowiązującym w Unii Europejskiej prawem.

Co się z kolei tyczy bezpieczeństwa, w tym przypadku platforma bazuje na nowoczesnych systemach ochrony danych wszystkich użytkowników. Mowa przede wszystkim o aktualnym certyfikacie SSL, którego 256-bitowe szyfrowanie jest gwarancją

bezpiecznego połączenia z serwerami kasynowymi. Ponadto właściciel kasyna funkcjonuje zgodnie z obowiązującymi zasadami polityki AML (Anti Money Laundering) oraz KYC (Know Your Customer).

Krótko mówiąc, Casino Vavada Poland to legalny operator, który prowadzi bezpieczną i licencjonowaną działalność hazardową w sieci.

Vavada kasyno online – najlepsze funkcje dla graczy

Szeroka selekcja gier

Błyskawiczne płatności

Polskojęzyczna obsługa klienta

Atrakcyjne bonusy i promocje

To tylko niektóre z wielu mocnych stron kasyna Vavada Poland. Jesteś gotów odkryć je wszystkie? Otwórz profil gracza i przekonaj się, co jeszcze dla Ciebie przygotowaliśmy!

Vavada – bonusy i promocje

Wielu graczy decyduje się na grę w kasynie internetowym ze względu na intratne oferty promocyjne. Dlatego też w naszym kasynie z myślą o nowych użytkownikach przygotowano rewelacyjny pakiet powitalny. Na tym jednak nie koniec,

ponieważ premie dla użytkowników dostępne są także za aktywną i lojalną grę.

Zobacz, jaki Vavada bonus najbardziej przypadnie Ci do gustu:

A to tylko część bogatej oferty, jaka dostępna jest w kasynie internetowym dla wszystkich graczy po zalogowaniu. Z pewnością znajdziesz tutaj odpowiednie gry i promocje dla siebie, co pozwoli Ci powalczyć o bogate nagrody i wysokie

wygrane.

Casino Vavada bonus powitalny bez tajemnic

Sprawa jest prosta: Ty zakładasz konto, a kasyno doładowuje Twój profil dodatkowymi środkami. Brzmi całkiem nieźle, prawda? Dla nowych graczy przygotowany został atrakcyjny bonus powitalny 100% od depozytu do wartości maksymalnej

5000 PLN oraz 100 darmowych spinów. Mamy dla Ciebie garść szczegółów, dzięki którym lepiej zrozumiesz zasady pakietu startowego za rejestrację profilu do gry:

Jak odebrać bonus powitalny Vavada Casino Polska? Sprawdź instrukcję krok po kroku:

Sięgnij po najbardziej atrakcyjną ofertę dla nowych graczy i już teraz odbierz swoje bonusy rejestracyjne w naszym kasynie internetowym. Poznaj też inne akcje promocyjne, w tym nader ciekawe turnieje kasynowe, w których do wygrania są

nawet dziesiątki tysięcy dolarów.

Vavada kod promocyjny: bonus 30 free spinów

Co powiesz na dodatkowe darmowe spiny za rejestrację konta w kasynie? Dostępny kod promocyjny wystarczy aktywować przy zakładaniu profilu gracza. Pozwala on otrzymać aż 30 free spinów na slot online o nazwie Towering Plays

Valhalla.

Ten przygotowany przez kasyno Vavada bonus bez depozytu nie wymaga wpłaty na konto, jest więc bonusem bez ryzyka utraty własnych środków finansowych. Za pomocą darmowych obrotów możesz wypróbować mechanikę gry w kasynie, a

także powalczyć o prawdziwe pieniądze za darmo. Pamiętaj jednak o warunkach obrotu — te wynoszą 40x, a czas na realizację wymogów to 14 dni.

Vavada cashback 10%

Raz na wozie, raz pod wozem — w naszym kasynie doskonale rozumiemy, że wygrywająca passa czasami kończy się przykrym niepowodzeniem. Cóż, wszystkie gry hazardowe są tutaj oparte na technologii losowości RNG, zapewniając uczciwość

i nieprzewidywalność rezultatów.

W związku z tym możesz aktywować w kasynie cashback, za pomocą którego zwrócimy Ci 10% utraconych na grę środków. Bonus przyznawany jest pierwszego dnia każdego miesiąca, żebyś mógł rozpocząć nowy rozdział w grze z dodatkowymi

środkami bonusowymi. Otrzymany zwrot masz prawo wykorzystać na kolejne rozgrywki w kasynie.

Vavada Casino Polska – aplikacja mobilna

Czy użytkownicy mobilni mogą pobrać Vavada App na swoje urządzenia z systemem Android lub iOS? Takie pytanie często pojawia się w przestrzeni, dlatego też spieszymy z odpowiedzią. Na chwilę obecną Vavada aplikacja mobilna nie jest

dostępna do pobrania na smartfony oraz tablety. Przygotowana została jednak alternatywna opcja, dzięki której możesz bez trudu obstawiać gry hazardowe na urządzeniu przenośnym.

Zarówno użytkownicy Android, jak i zwolennicy iOS, mogą sięgnąć po mobilną wersję strony internetowej naszego kasyna. Jest ona dostępna z poziomu dowolnej przeglądarki, co znacznie ułatwia i przyspiesza dostęp do Twoich ulubionych

gier.

Nie musisz nic ściągać i instalować na swoim urządzeniu – po prostu otwórz mobilną przeglądarkę, wpisz adres witryny kasyna, a następnie przejdź do gry. Mobilne kasyno Vavada Polska oferuje pełen dostęp do wszystkich swoich usług

i zasobów. Zdecydowanie polecamy takie rozwiązanie, jeśli chcesz mieć natychmiastowy dostęp do ulubionych gier zawsze pod ręką.

Jak założyć nowe konto? Rejestracja Vavada kasyno online

Dostęp do kilku tysięcy gier hazardowych, możliwość odblokowania bonusów, a także wiele innych korzyści jest na wyciągnięcie ręki. Wystarczy utworzyć nowy profil gracza. Prosty i nieskomplikowany formularz zapewnia starannie przygotowana

przez kasyno Vavada rejestracja dla nowych klientów. Przekonaj się, jak łatwo krok po kroku dołączyć do gry:

W serwisie kasynowym w Polsce proces rejestracji dla nowych użytkowników został maksymalnie uproszczony. Nie musisz podawać żadnych danych osobowych w formularzu, ponieważ wszelkie dodatkowe informacje możesz uzupełnić w późniejszym

terminie.

Jak zalogować się na nowy profil gracza w kasynie?

Równie łatwe i szybkie, co rejestracja dla nowych graczy, jest też logowanie na profil kasynowy. W tym przypadku wystarczy postępować zgodnie z poniższymi wskazówkami, aby błyskawicznie rozpocząć korzystanie ze swojego konta online:

Proces rejestracji i logowania jest na tyle przejrzysty, że poradzą sobie z tym nawet początkujący entuzjaści kasyn online. Możesz zatem już teraz rozpocząć swoją przygodę z najlepszym kasynem – wystarczy parę sekund, aby stać

się pełnoprawnym użytkownikiem Vavada Poland.

Metody płatności – wpłaty depozytów, wypłaty wygranych

Kiedy już staniesz się posiadaczem zarejestrowanego profilu gracza, możesz od razu przejść do realizacji wpłaty depozytu na swoje saldo. Pamiętaj przy tym o możliwości uzyskania bonusu powitalnego za pierwszą wpłatę: czeka na Ciebie

100% od depozytu do 1000 USD, 100 free spinów, a także 10% cashbacku.

I tu pojawia się pytanie, jakie metody płatności kasyno honoruje wśród polskich graczy? Szczegółowa dostępność może zależeć od Twojej aktualnej lokalizacji, dlatego warto sprawdzić, jak wyglądają wszystkie dostępne opcje płatnicze.

Jest ich łącznie ponad 30, a oto najpopularniejsze z nich:

Porównaj zasady korzystania z poszczególnych sposobów wpłaty i wypłaty, jakie kasyno udostępnia w Twoim kraju. W ten sposób odpowiednio przygotowujesz się do realizacji swoich transakcji i nie będziesz musiał tracić czasu na dostosowanie się

do aktualnych wymogów finansowych.

Jak wpłacić depozyt na konto gracza?

W kasynie Vavada depozyt możesz zrealizować błyskawicznie na wiele różnych sposobów. Wśród dostępnych opcji polscy użytkownicy szczególnie upodobali sobie kilka metod płatności, które porównujemy w poniższej tabeli:

Dzięki natychmiastowemu przetwarzaniu wszystkich wpłat depozytu, możesz niezwłocznie przejść do gry na prawdziwe pieniądze. Transakcje płatnicze są tutaj pod ścisłą ochroną, więc nie musisz obawiać się o swoje dane osobowe. Aby zlecić

wpłatę środków na swoje konto, skorzystaj z naszych wskazówek:

To wszystko! Nie czekaj ani chwili dłużej – wpłać depozyt i rozpocznij grę w naszym kasynie!

Jak wypłacić wygrane na rachunek osobisty?

Wygrane pieniądze w kasynie internetowym możesz wypłacić na swoje konto osobiste. Żeby to zrobić, wystarczy dosłownie kilka sekund i parę kliknięć. W kasynie Vavada wypłaty możesz zrealizować w następujący sposób krok po kroku:

Polscy gracze powinni być świadomi ograniczeń w zakresie wypłat, jakie ustalone zostały w regulaminie kasyna. Nasze kasyno opinie o płatnościach ma dobre również ze względu na wysokie limity wypłat, które uzależnione są od poziomu

w programie lojalnościowym:

Uwaga: limit wypłat krypto wynosi 1 000 000 USD miesięcznie. Wszelkie ustalone przez kasyno ograniczenia kwotowe obowiązują w dni powszechnie. Realizacja wypłaty wygranych w weekendy ma limit 2000 USD dziennie. Płatności można realizować

codziennie i całodobowo, zaś ich przetworzenie zajmować może od kilku minut do maksymalnie 24 godzin.

Oferta gier hazardowych online

Jednym z największych atutów kasyna jest bogata oferta gier hazardowych w kilku najważniejszych kategoriach. Znajdziesz tutaj nie tylko popularne sloty online, ale również szereg gier stołowych i karcianych, a także fantastyczne

kasyna na żywo. Nasza platforma hazardowa ściśle współpracuje z najlepszymi dostawcami oprogramowania, takimi jak NetEnt, Microgaming, Play’n GO, Pragmatic Play czy też Evolution Gaming. Dzięki temu selekcja gier kasynowych

jest niezwykle zróżnicowana, a zarejestrowani użytkownicy mogą wybierać spośród setek tytułów.

Warto również dodać, że w kasynie możesz obstawiać sloty online za darmo. Zachęcamy do wypróbowania różnych automatów do gry w wersji demo, która nie wymaga od gracza wpłaty depozytu na saldo główne. Jest to idealna opcja dla każdego,

kto chce zapoznać się z mechaniką obstawiania maszyn hazardowych bez ryzykowania własnych środków finansowych.

Spośród ponad 4500 gier, jakie znajdziesz w bibliotece naszego kasyna, wybraliśmy dla Ciebie TOP 3 najchętniej wybierane maszyny. Poznaj je bliżej, aby wiedzieć, czego możesz się spodziewać po najlepszych grach kasynowych w Polsce!

Aviator – najlepsza gra crash na świecie

W kasynie Vavada Aviator cieszy się ogromnym zainteresowaniem użytkowników, którzy cenią sobie błyskawiczną rozgrywkę i wysoką jakość grafiki. Jest to stosunkowo nowa gra z kategorii crash games, a jej twórcą jest studio Spribe.

Rozgrywka polega na tym, że gracz ma na początku postawić pojedynczą lub podwójną stawkę na kolejną rundę. Gdy ta się rozpocznie, na ekranie pojawi się samolot, który będzie się wznosił, zwiększając tym samym mnożnik potencjalnych wygranych.

Zadaniem gracza jest wypłata wygranej za pomocą przycisku „Cashout” przed odlotem tytułowego Aviatora z ekranu.

Aviator RTP ma na poziomie około 97%, co gwarantuje spory poziom zwrotu stawek w formie wygranych dla graczy. Prosta rozgrywka, szybkie ładowanie się kolejnych rund, a także dostęp do statystyk sprawiają, że obstawianie Aviatora to rozrywka

na najlepszym możliwym poziomie!

Gates of Olympus – popularny slot Pragmatic Play

Jeżeli szukasz znanych i lubianych automatów online, koniecznie sprawdź ofertę dewelopera Pragmatic Play. Wśród slotów dostępnych w kasynie Vavada Gates of Olympus tego renomowanego twórcy gier cieszy się ogromną popularnością. Slot pozwala

Ci wczuć się w klimat starożytnej Grecji, towarzysząc bogom Olimpu w kręceniu bębnem maszyny hazardowej.

Stawki na zakłady w Gates of Olympus Vavada Casino mieszczą się w przedziale od 0,01 do 0,50. Dzięki temu nie musisz obstawiać za duże pieniądze, aby rozegrać parę rund. Pragmatic Play ustawił wskaźnik zwrotu RTP Gates of Olympus na poziomie

96,50%. Dołącz do gry, testując automat online za pomocą wersji demonstracyjnej, która dostępna jest w naszym kasynie całkowicie za darmo!

Tigers Gold – polecany automat online marki Booongo

Kolejna polecana przez graczy opcja to gra Tigers Gold stworzona przez studio Booongo. Ta gra w Vavada Casino opinie ma bardzo dobre, dzięki czemu od lat pozostaje częstym wyborem zarówno nowych, jak i stałych klientów. Slot online miał

swoją premierę w roku 2020 i bazuje na tradycyjnych rozwiązaniach graficznych oraz technologicznych.

W przypadku slotu Tigers Gold RTP wynosi około 95%, zmienność automatu jest średnia bądź wysoka, a maszyna posiada 25 linii płatniczych. Mechanizm rozgrywki wzbogacają dodatkowe symbole Wild i Scatter, a także dostępne rundy bonusowe.

Polecamy każdemu, kto ma ochotę powalczyć o atrakcyjne wygrane.

Kasyno na żywo

Sekcja gier na żywo w kasynie online to nie lada gratka dla wszystkich osób, które chciałyby się poczuć jak w prawdziwym kasynie. Trzeba w tym miejscu podkreślić, że kasyno na żywo to sekcja rozgrywek przy stołach obsługiwanych

przez prawdziwych krupierów. Są to profesjonaliści zatrudniani przez czołowych dostawców oprogramowania hazardowego, a obstawianie odbywa się całkowicie w czasie rzeczywistym.

Kasyno współpracuje z samą czołówką deweloperów oprogramowania live:

Oferta stale się powiększa, a wśród dostępnych gier znajdziesz stoły do ruletki, pokera, blackjacka czy bakarata. Do tego dochodzą również teleturnieje online na żywo, a wśród nich również popularna gra Sweet Bonanza Candyland.

Zdecydowanie warto rzucić okiem na dostępność gier kasynowych na żywo, gdyż gwarantują one niepowtarzalny zastrzyk emocji.

Vavada Casino Polska – sloty online

Automaty online stanowią w ofercie kasyna internetowego największy wybór gier hazardowych. Znajdziesz tutaj ponad 4000 tytułów, które dostarczane są przez ponad 40 topowych twórców oprogramowania kasynowego. Sprawdź, które sloty

online aktualnie cieszą się największą popularnością wśród polskich graczy naszego kasyna:

Starannie dobrane automaty do gry charakteryzują się atrakcyjnymi warunkami rozgrywki. Średni poziom wskaźnika zwrotu do gracza (RTP) slotów w naszym serwisie przekracza wynik 95%. Możesz typować maszyny o niskiej, średniej, a także wysokiej

zmienności i różnych opcjach bonusowych.

Warto dodać, że w kasynie dostępne są liczne turnieje, które pozwalają powalczyć o podział potężnych puli nagród. Jackpoty osiągają często kilkadziesiąt tysięcy dolarów, a udział w turniejach promocyjnych jest całkowicie bezpłatny. Wystarczy

kręcić bębnami slotów, które wchodzą w ofertę danej akcji. Im więcej grasz, tym większe szanse masz na uzyskanie atrakcyjnych wygranych.

Poker w ofercie kasyna Vavada Polska

Choć brakuje tutaj oddzielnej zakładki dla najpopularniejszej gry karcianej w kasynach online, oferta Vavada poker prezentuje się naprawdę dobrze. Dostępne stoły z grami znajdziesz zarówno w zakładce kasyna na żywo, jak też gier

stołowych. Możesz zatem obstawiać pokera z prawdziwymi krupierami lub w wersji wirtualnej – wybór należy tylko do Ciebie!

Pokerzyści mogą sięgać po nowoczesne rozwiązania technologiczne, jakie oferuje portal online. Przygotowane są różne wersje pokera, od Texas Hold’em po bardziej egzotyczne odmiany, takie jak Omaha czy Caribbean Stud Poker. Regularnie

organizowane są również fachowe turnieje pokerowe, w których można wygrać atrakcyjne nagrody pieniężne.

Gra Plinko na stronie internetowej kasyna

Jeszcze jedna fantastyczna opcja gry dla wszystkich zarejestrowanych użytkowników naszego kasyna online. Dostępna w bibliotece Vavada Plinko to popularna gierka, która przenosi rozwiązania gry planszowej do Internetu. Fani tej

rozgrywki online mogą skorzystać z kilku wersji automatu:

Zapoznaj się ze szczegółowymi zasadami poszczególnych alternatyw tej rozchwytywanej rozgrywki. Gdy tylko będziesz gotów do gry, to od razu przejdź do obstawiania maszyny hazardowej w naszym serwisie. Z pewnością nie pożałujesz

tej decyzji, gdyż rozrywka w Plinko gwarantuje emocje nie z tej ziemi!

Stoły z bakaratem w kasynie

W sekcji kasyna Vavada baccarat cieszy się rosnącą popularnością, co sprawia, że w lobby pojawiają się nowe wersje tej gry karcianej. Możesz obstawiać nie tylko wirtualne stoły z bakaratem, ale również rozgrywki z prawdziwymi krupierami

w kasynie na żywo. Dostawcami ulubionych gier naszych użytkowników są między innymi Evolution Gaming, a także BetGames.

Rozpocznij grę i obstawiaj różne wersje znanych i lubianych gier karcianych czy stołowych. W kasynie znajdziesz wiele ciekawych opcji, które gwarantują moc zabawy zarówno dla nowych graczy, jak i starych kasynowych wyjadaczy.

Obsługa klienta Vavada Casino Polska

Czasami może się zdarzyć, że podczas gry w naszym kasynie internetowym napotkasz jakieś problemy lub ograniczenia. Bez obaw jednak, ponieważ wiele spraw możesz rozwiązać sam, korzystając z naszego profesjonalnego wsparcia klienta.

Sięgnij do regulaminu kasyna, zapoznaj się z najczęściej zadawanymi pytaniami i znajdź odpowiedź na swoje wątpliwości.

Jeżeli jednak potrzebujesz dodatkowej pomocy, poznaj dostępne metody kontaktu z biurem obsługi klienta. Vavada opinie o wsparciu technicznym ma bardzo dobre, gdyż pomoc działa całodobowo i przez siedem dni w tygodniu. Sprawdź,

jak możesz skontaktować się z konsultantami naszej platformy hazardowej:

W kasynie znajdziesz wsparcie w języku polskim, dzięki czemu bez żadnych przeszkód uzyskasz oczekiwaną pomoc. Skorzystaj z dostępnych opcji kontaktu, które gwarantują fachowe odpowiedzi na wszelkie pytania i wątpliwości.

Czym jest gra Aviator w Vavada Casino?

Dostępny w kasynie Vavada Polska Aviator to innowacyjna gra hazardowa, która różni się od tradycyjnych automatów. Nie ma tutaj bębna do obracania, linii płatniczych czy też free spinów. Jest za to dynamika, której nie powstydziłyby

się nawet innowacyjne video sloty.

Głównym celem rozgrywki w tej popularnej grze crash jest przewidywanie, kiedy z Twojego ekranu odleci wznoszący się w górę samolot. Im dłużej tytułowy cud techniki awiacyjnej pozostaje w powietrzu, tym większy mnożnik potencjalnej

wygranej.

Wyzwaniem stojącym przed graczem jest kliknięcie przycisku wypłaty wygranych w odpowiednim momencie, ponieważ wraz z odlotem samolotu tracisz swoją stawkę.

W serwisie Vavada Aviator cieszy się ogromnym zainteresowaniem zarejestrowanych graczy. Sporą popularność ta innowacyjna gierka kasynowa zawdzięcza wielu czynnikom. Zacznijmy od przedstawienia kilku kluczowych informacji:

Najważniejsze cechy i funkcje gry Vavada Aviator

Gra Aviator Vavada Casino to jedyna w swoim rodzaju rozgrywka w stylu crash game. Ta kategoria rozgrywek hazardowych zdobywa coraz większą popularność na całym świecie. Wzrost zainteresowania zawdzięcza nieskomplikowanej rozgrywce,

szybkiemu obstawianiu kolejnych rund, a także przejrzystemu układowi poszczególnych elementów. Aviator jest swego rodzaju prekursorem tego rodzaju automatów, dlatego też od lat pozostaje numerem jeden wśród graczy kasyna Vavada.

Zastanawiasz się, dlaczego warto przetestować tę maszynę do gry w naszym kasynie? Zwróć uwagę na najciekawsze funkcje, które wyróżniają Aviatora na tle innych automatów:

Sięgnij po grę Aviator w Vavada Casino Polska i powalcz o wygrane!

Jak rozpocząć grę w Aviator Vavada Casino?

Jeżeli chcesz przejść do obstawiania w kasynie Vavada gry Aviator, możesz zrobić to już w kilka minut. Przygotowaliśmy dla Ciebie krótki poradnik krok po kroku, dzięki któremu łatwo przejdziesz do rozgrywki za darmo lub za prawdziwe

pieniądze:

W kasynie Vavada rejestracja jest niezbędna do gry na pieniądze. Warto pamiętać, że nasza platforma oferuje również tysiące innych automatów, a także szereg godnych uwagi premii i benefitów za lojalną grę.

Bonus powitalny za rejestrację w Vavada Casino

Nowi gracze na mogą liczyć na atrakcyjny bonus powitalny, który dostępny jest już po rejestracji konta do gry. W przypadku kasyna Vavada bonus na start wymaga tylko wpłaty depozytu, a

wówczas nowy użytkownik uzyska dostęp do następujących promocji:

100 free spinów na slot Great Pigsby Megaways (Relax Gaming, RTP 96,08%)

100% od pierwszej wpłaty do 1000 USD

10% zwrotu co tydzień w formie cashback

Jak otrzymać swój bonus? To bardzo proste, zobacz sam:

Uzyskane w kasynie Vavada bonusy możesz przeznaczyć na rozegranie rund bez ryzyka utraty własnych środków finansowych. Jest to świetna okazja dla każdego, kto chce przetestować nasze kasyno za darmo.

Vavada Aviator – na czym polega rozgrywka?

Aviator to gra, w której równie istotny jest refleks, co przygotowana przez gracza strategia obstawiania. Na początku dobierasz pojedynczą lub podwójną stawkę, jaką zagrasz w kolejnej rundzie. Gdy ta się zacznie po końcowym odliczaniu,

wówczas na ekranie pojawi się wznoszący się samolot.

Im dłużej samolot leci, tym bardziej rośnie mnożnik potencjalnych wygranych. Teraz wszystko jest w Twoich rękach. Musisz zdecydować o najlepszym momencie na kliknięcie opcji „cashout”, za pomocą których uzyskasz swoje zdobycze finansowe.

Żeby lepiej przygotować się do gry, warto przetestować grę w wersji demo. Jest to opcja dostępna w kasynie Vavada, dzięki której możesz za darmo rozegrać parę rund, aby poznać wszystkie opcje rozgrywki.

Oficjalna strona internetowa Vavada casino PL

| January 22, 2026

Oficjalna strona internetowa Vavada casino PL

Oficjalna strona kasyna Vavada to platforma hazardowa online, którą można odwiedzić na głównych domenach takich jak Vavada.com albo mirror-stronach dedykowanych Polsce i innym krajom europejskim. Serwis istnieje od 2017 roku i zdobył szeroką bazę graczy dzięki ogromnej bibliotece gier, licznym promocjom i prostemu systemowi rejestracji. Kasyno działa na licencji z Curacao – oznacza to, że jest formalnie zarejestrowane i podlega zasadom regulacyjnym tej jurysdykcji, ale nie ma szczególnego nadzoru ze strony europejskich organów stricte hazardowych.

Strona jest dostępna w wielu językach, w tym po polsku, i oferuje możliwość szybkiego przejścia przez proces logowania lub rejestracji. Interfejs użytkownika jest podzielony na wygodne sekcje – konto gracza, portfel z historią transakcji i metodami płatności, sekcja bonusów oraz status lojalnościowy gracza. W panelu konta znajdziesz również komunikaty od kasyna oraz informacje o aktywnych promocjach.

Platforma umożliwia grę zarówno na komputerach, jak i urządzeniach mobilnych – bez konieczności instalowania osobnej aplikacji, ponieważ mobilna wersja strony oferuje funkcjonalność pełną jak na desktopie. Dodatkowo kasyno obsługuje wiele walut i ponad 17 metod płatności, co daje dużą elastyczność osobom, które preferują różne sposoby depozytów lub wypłat.

Kolekcja gier

Gdy spojrzysz na kolekcję gier dostępnych w Vavada kasyno, to pierwsze, co uderza – ogrom i różnorodność, która dosłownie zasypuje nowego gracza już na etapie przeglądania katalogu. Oficjalne dane mówią o ponad 4 500 tytułach z całego świata – od automatów typu slot po stoły z żywymi krupierami i klasyczne gry stołowe.

Sloty – serce kolekcji

Sloty stanowią lwią część całej biblioteki – często ponad 90% wszystkich dostępnych gier. Znajdziesz tu klasyczne automaty owocowe, nowoczesne video sloty z wieloma liniami wygranych oraz tytuły typu Megaways. Popularne przykłady gier to m.in. Sweet Bonanza, Book of Ra, Gates of Olympus, The Dog House czy Big Bass Bonanza – każda z nich ma własne unikalne bonusy w grze, darmowe rundy i mechaniki, które porywają uwagę.

Gry stołowe i karciane

Poza slotami, Vavada oferuje ruletkę, blackjacka, baccarat, a także inne klasyki stołowe. To mniej rozbudowana sekcja niż sloty, ale wciąż stanowi solidną opcję dla osób, które wolą strategiczną rozgrywkę nad prostym kręceniem bębnów.

Live casino – emocje jak w realu

Jeżeli chcesz poczuć atmosferę prawdziwego kasyna, dostępna jest sekcja live dealer, gdzie gra toczy się na żywo, a profesjonalni krupierzy prowadzą ruletkę, blackjacka i inne rozgrywki w czasie rzeczywistym. Transmisje odbywają się 24/7 i bywają popularne w godzinach wieczornych, gdy aktywność graczy rośnie.

Dostawcy oprogramowania

Kasyno współpracuje z dużą liczbą renomowanych dostawców gier – w katalogu pojawiają się tacy jak Pragmatic Play, Evolution Gaming, Relax Gaming, Push Gaming, NetEnt, Play’n GO, ELK Studios i wielu innych. Dzięki temu tytuły są nie tylko różnorodne, ale często aktualizowane i technicznie dopracowane.

Bonusy i promocje

System bonusów w Vavada casino online to coś, co przyciąga wiele osób – i to już od pierwszego kontaktu z kasynem. Oferta jest złożona, obejmuje bonusy powitalne, darmowe spiny, promocje cykliczne i elementy programu lojalnościowego.

Bonus powitalny

Nowi gracze otrzymują pakiet powitalny – klasyczny zestaw to 100% bonus od pierwszej wpłaty z możliwością zwiększenia salda nawet do 1000 $ lub równowartości w innej walucie oraz dodatkowe 100 darmowych spinów do wykorzystania na konkretnych slotach. Minimalna wpłata, aby aktywować ten bonus, to zazwyczaj 1 EUR / 1 $.

Warunki obrotu (czyli tzw. wager) przy bonusie depozytowym zwykle wynoszą x35, co oznacza, że środki bonusowe trzeba obrócić 35 razy przed możliwością wypłaty wygranych z bonusu. W przypadku darmowych spinów również obowiązują warunki obrotu, często x20-x40 zależnie od promocji i zasad konkretnej nagrody.

Darmowe spiny i bonus bez depozytu

Oprócz klasycznego pakietu powitalnego, kasyno regularnie oferuje darmowe spiny bez depozytu – np. 100 darmowych spinów za samo założenie konta, które można wykorzystać na wybranych automatach, często z limitem na maksymalną wysokość wypłaty wygranych z tych spinów.

Cashback i promocje stałe

Vavada casino ma też mechanizm cashback, najczęściej na miesięcznej zasadzie – gracze mogą odzyskać część przegranych środków (np. 10% różnicy między łącznymi zakładami a wygranymi) w formie bonusowej.

Program VIP i turnieje

Platforma posiada także program lojalnościowy z kilkoma poziomami – im więcej grasz i obracasz depozytami, tym wyższe statusy i lepsze bonusy możesz uzyskać, w tym wyższe limity wypłat lub indywidualne oferty. Regularnie organizowane są też turnieje z nagrodami, w których pula nagród może być znaczna.

Metody płatności i wypłaty środków

Jednym z kluczowych aspektów każdego kasyna online jest wygoda i bezpieczeństwo transakcji finansowych. Vavada casino oferuje ponad 17 metod płatności, które obejmują zarówno tradycyjne karty bankowe Visa i Mastercard, jak i nowoczesne portfele elektroniczne takie jak Skrill, Neteller czy ecoPayz. Dla graczy preferujących kryptowaluty dostępne są również opcje depozytów i wypłat w Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin oraz innych popularnych walutach cyfrowych, co zapewnia dodatkową warstwę anonimowości i szybkości przetwarzania transakcji.

Minimalna kwota depozytu jest zazwyczaj bardzo niska – często wynosi zaledwie 1 EUR lub równowartość w innej walucie, co sprawia, że platforma jest dostępna nawet dla graczy z niewielkim budżetem. Jeśli chodzi o wypłaty, kasyno deklaruje czas przetwarzania od kilku minut do 24 godzin w zależności od wybranej metody, choć w praktyce czas ten może się wydłużyć ze względu na procesy weryfikacyjne, szczególnie przy pierwszych wypłatach lub wyższych kwotach.

Bezpieczeństwo i odpowiedzialna gra

Vavada stosuje standardowe protokoły szyfrowania SSL, które chronią dane osobowe graczy oraz informacje finansowe podczas przesyłania ich przez internet. Kasyno wymaga również weryfikacji tożsamości (KYC) przed dokonaniem pierwszej wypłaty – gracze muszą przesłać kopię dokumentu tożsamości oraz potwierdzenie adresu zamieszkania, co jest standardową praktyką w branży hazardowej online i ma na celu zapobieganie praniu pieniędzy oraz oszustwom.

Platforma udostępnia również narzędzia odpowiedzialnej gry, takie jak możliwość ustawienia limitów depozytów dziennych, tygodniowych lub miesięcznych, a także opcję samowyłączenia konta na określony czas. Są to ważne mechanizmy dla graczy, którzy chcą kontrolować swoje wydatki i unikać problematycznych zachowań hazardowych. Warto jednak pamiętać, że licencja z Curacao nie zapewnia takiego samego poziomu ochrony konsumenta jak licencje wydawane przez europejskie organy regulacyjne, takie jak Malta Gaming Authority czy UK Gambling Commission.

Obsługa klienta

Kasyno Vavada oferuje wsparcie techniczne i pomoc dla graczy przez całą dobę za pośrednictwem czatu na żywo, który jest dostępny bezpośrednio na stronie internetowej. Alternatywnie gracze mogą skontaktować się z zespołem obsługi klienta przez email. Czas odpowiedzi na czacie na żywo jest zazwyczaj krótki – kilka minut w godzinach szczytu – natomiast odpowiedzi na wiadomości email mogą zająć do 24 godzin. Obsługa jest dostępna w kilku językach, co ułatwia komunikację graczom z różnych krajów. Warto podkreślić, że jakość obsługi klienta jest istotnym czynnikiem przy wyborze kasyna, ponieważ szybka i kompetentna pomoc może znacząco wpłynąć na ogólne doświadczenie użytkownika, szczególnie w przypadku problemów z transakcjami lub weryfikacją konta.

If It Isn’t The Same, It’s Different!

| December 4, 2025

MERCK SERONO S.A., Appellant v. HOPEWELL PHARMA VENTURES, INC., (Presidential)

Date of Decision: October 30, 2025

Panel: Before HUGHES, LINN, and CUNNINGHAM, Circuit Judges. LINN, Circuit Judge.

Summary:

Merck Serono S.A. (“Merck”) appeals the determinations by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) in two consolidated inter partes reviews (“IPR”). In this case, the Board held several claims of Merck’s U.S. Patent No. 7,713,947 (“’947 patent”) and U.S. Patent No. 8,377,903 (“’903 patent”) unpatentable as obvious over a combination of Bodor and Stelmasiak. The Patents in question related to oral formulations of cladribine to treat MS.

In 2002, Serono partnered with IVAX Corporation (“Ivax”) to develop oral cladribine to treat MS. Serono was acquired by Merck in 2006. Under their joint research agreement, Merck would “‘conduct clinical trials’ to determine ‘the dose, safety, and/or efficacy’” of cladribine oral tablets, and Ivax would “develop an oral dosage formulation of [cladribine] in tablet or capsule form suitable for use in clinical trials and commercial sale.” On March 26, 2004, Ivax employees Drs. Bodor and Dandiker filed the Bodor international patent application (the primary reference used by Hopewell here). The application was published less than one year before the effective filing date of the patents in-suit, which were each filed December 22, 2004. Both patents list as inventors: Drs. De Luca, Ythier, Munafo, and Lopez Bresnahan (collectively, “named inventors”). All four were employees of Serono and, in at least some way, were a part of the development team that developed the claimed oral cladribine regimen back in 2002 (as evidenced by meeting minutes).

Hopewell Pharma Ventures, Inc. (“Hopewell”) filed two IPRs, respectively challenging claims of the ’947 patent and the ’903 patent as obvious over Bodor and Stelmasiak. The Board held that all challenged claims were unpatentable as obvious thereover. In doing so, the Board rejected patentee’s legal argument that “a reference’s disclosure of the invention of a subset of inventors is disqualified as prior art against the invention of all the inventors.” Id. at 36 (emphasis in original). The rule of In re Land, 368 F.2d 866 (CCPA 1966), that any difference in the “inventive entity” between the reference disclosure and the challenged claims—whether adding or subtracting inventors—rendered the reference a disclosure “by another” and therefore available as prior art, was affirmed. The Board also found there was insufficient corroboration evidence that De Luca’s contribution provided an inventive contribution found in Bodor, as would be required to exclude the disclosure from the prior ar.

Ultimately the CAFC affirmed the Board’s determinations.

Under pre-AIA § 102(e), a patent is anticipated if “the invention was described in . . . a patent granted on an application for patent by another filed in the United States before the invention by the applicant for patent.” 35 U.S.C. 102(e) (emphasis added).

The question presented to the CAFC in this appeal is “whether and to what extent a disclosure invented by fewer than all the named inventors of a patent may be deemed a disclosure “by another” and thus included in the prior art, or whether the disclosure should properly be treated as “one’s own work” and therefore excluded from the prior art.”

Merck argued for the latter, but the CAFC found for the first.

Merck focuses on the following two sentences in Applied Materials, Inc. v. Gemini Res. Corp., 835 F.2d 279 (Fed. Cir. 1987):

However, the fact that an application has named a different inventive entity than a patent does not necessarily make that patent prior art.

Id. at 281 (citing In re Kaplan, 789 F.2d 1574, 1576 (Fed. Cir. 1986)); Appellant’s Opening Br. 30–31. And:

Even though an application and a patent have been conceived by different inventive entities, if they share one or more persons as joint inventors, the 35 U.S.C. § 102(e) exclusion for a patent granted to ‘another’ is not necessarily satisfied.

Applied Materials, 835 F.2d at 281 (emphasis added); Appellant’s Opening Br. 29.

Merck essentially argued that the Courts have rejected a bright-line rule requiring an identical inventive entity to exclude a reference as not “by another.”

The CAFC held that Merck overreads Applied Materials. The CAFC clarified that the decision did not rely on the fact that two of the three named inventors in the later patent were named in the earlier reference patent. Instead, the decision rested on the fact that the later patent and the earlier reference patent were descendants of the same application. The CAFC emphasized that it is erroneous to place too much reliance on the inventive entity “named” in the earlier reference patent: “[T]he fact that an application has named a different inventive entity than a patent does not necessarily make that patent prior art.” Id. (emphasis added). Instead, like in Land, the key question is whether the disclosure in the earlier reference evidenced knowledge by “another” before the patented invention.

The CAFC stated that:

Our case law—in particular, Land—precludes our adoption of the policy argument presented by Merck. As those cases make clear, for a reference not to be “by another,” and thus unavailable as prior art under pre-AIA § 102(e), the disclosure in the reference must reflect the work of the inventor of the patent in question. That is clear enough when a single inventor is involved. What should also be clear is that when the patented invention is the result of the work of joint inventors, the portions of the reference disclosure relied upon must reflect the collective work of the same inventive entity identified in the patent to be excluded as prior art. That showing may be made by fewer than all the inventors but nonetheless must evince the joint work of them all to avoid being considered a work “by another” under the statute. Any incongruity in the inventive entity between the inventors of a prior reference and the inventors of a patent claim renders the prior disclosure “by another,” regardless of whether inventors are subtracted from or added to the patent.

Here, ultimately, Merck failed to provide sufficient evidence that one of the inventors had made an inventive contribution to the relevant disclosure in Bodor, but even if Merck had shown such a contribution, the evidence did show that Bodor’s inventors had made significant contributions, so the reference would still qualify as “by another”.

Next, Merck next argued that it was “surprised by the Board’s application of the above-discussed rule requiring complete identity of inventive entity because the rule is contrary to several provisions of the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (“MPEP”).”

Merck relies on the following MPEP sections. Appellant’s Opening Br. 34. MPEP § 2132.01:

An inventor’s or at least one joint inventor’s disclosure of his or her own work within the year before the application filing date cannot be used against the application as prior art.

And MPEP § 2136.05(b):

[E]ven if an inventor’s or at least one joint inventor’s work was publicly disclosed prior to the patent application, the inventor’s or at least one joint inventor’s own work may not be used against the application subject to preAIA 35 U.S.C. 102 unless there is a time bar.

Hopewell responded that Merck “did not lack notice of the rule because the MPEP expressly adopts the rule of Land in § 2136.04 (titled “Different Inventive Entity; Meaning of ‘By Another’”)”.

The CAFC agreed with Hopewell. Moreover, the CAFC noted that “To the extent the MPEP describes our case law differently, that interpretation does not control,” but nonetheless failed to agree that the MPEP was different.

Accordingly, the CAFC found that Bodor was proper prior art. Once confirmed, the Court went on to affirm the Board’s determination that the challenged claims were obvious in view of Bodor and Stelmasiak,

Comments:

- The phrase “by another” requires complete identity of the inventive entity to exclude a reference as prior art. In order to disqualify overlapping inventor references, corroborated evidence must be provided that all named inventors contributed to the inventive aspect of prior relevant disclosure. Thus, it is important for inventors working under joint research agreements to keep up-to-date lab and meeting notes that could aid in establishing such corroborated evidence.

- MPEP is not controlling over case law where interpretation is distinct.

when an apparatus claim depends on functioning claim to describe the apparatus, what the device does and how it does it are highly relevant to understanding what the device is

| October 22, 2025

ROTHSCHILD CONNECTED DEVICES INNOVATIONS, LLC v. COCA-COLA COMPANY

Date of Decision: October 21, 2025

Before: Prost (author), Lourie, and Stoll

Summary:

The CAFC agreed with the decision of the district court and affirmed the summary judgement of noninfringement because by looking at the claim language and the specification, the claimed communication module must be configured to perform its steps in the order in which they are written, thereby allowing a narrow claim construction.

Details:

Rothschild Connected Devices Innovations, LLC (“Rothschild”) owns U.S. Patent No. 8,417,377 (“the ’377 patent) and sued Coca-Cola Co. (“Coca-Cola”) for infringing the ’377 patent in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia, which granted summary judgement of noninfringement.

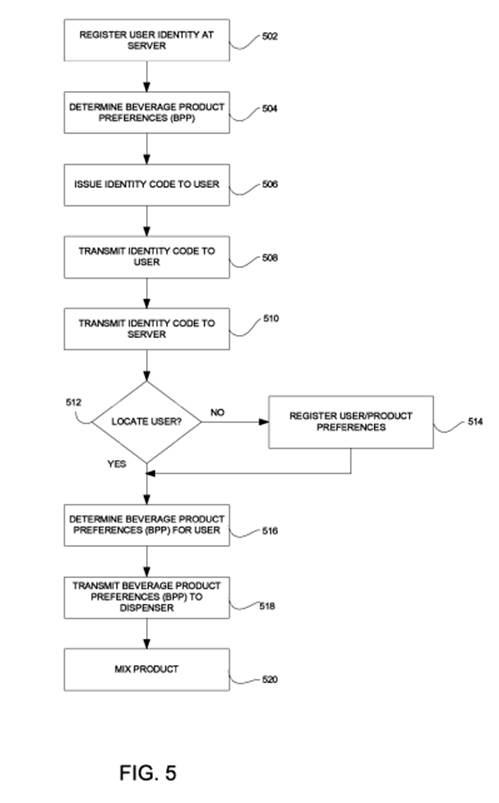

At issue is an independent claim 11, which reads as follows:

A beverage dispenser comprising:

at least one compartment containing an element of a beverage;

at least one valve coupling the at least one compartment to a dispensing section configured to dispense the beverage;

a mixing chamber for mixing the beverage;

a user interface module configured to receive an[] identity of a user and an identifier of the beverage;

a communication module configured to transmit the identity of the user and the identifier of the beverage to a server over a network, receive user generated beverage product preferences based on the identity of the user and the identifier of the beverage from the server and communicat[e] the user generated beverage product preferences to controller; and

the controller coupled to the communication module and configured to actuate the at least one valve to control an amount of the element to be dispensed and to actuate the mixing chamber based on the user gene[r]ated beverage product preferences.

At issue in this appeal is whether the claimed communication module must be configured to perform its steps in the order in which they are written:

(1) “transmit the identity of the user and the identifier of the beverage to a server over a network”;

(2) “receive user generated beverage product preferences based on the identity of the user and the identifier of the beverage from the server”; and

(3) “communicat[e] the user generated beverage product preferences to controller.”

The district court held that the communication module must be configured to perform these steps in that particular order.

The CAFC agreed with the decision of the district court and affirmed the summary judgement of noninfringement.

The CAFC applied a two-part test for determining if steps that do not otherwise recite an order “must nonetheless be performed in the order in which they are written.”

First, the CAFC look at the claim language to determine if, as a matter of logic or grammar, they must be performed in the order written.

Second, if not, the CAFC review the specification to determine whether it directly or implicitly requires such construction.

If not, the sequence in which such steps are written is not a requirement.

In this case, the CAFC held that as a matter of logic or grammar, the communication module must be configured to perform its steps in the order in which they are written – to a server and from the server.

In particular, the CAFC noted that the use of “based on” indicates that the first step precedes the second step.

Furthermore, the CAFC noted that the specification clearly contains language and figures (the below Fig. 5) describing this order and does not contain any suggestion as to Rothschild’s contrary claim interpretation.

Rothschild argued that independent claim 11 is an apparatus claim, and therefore the claim does not require ordered steps (this apparatus claim covers what a device is, not what a device does).

The CAFC noted that while apparatus claims focus on the structure instead of the operation or use, when an apparatus claim depends on functioning claim to describe the apparatus, what the device does and how it does it are “highly relevant to understanding what the device is.”

Accordingly, the CAFC affirmed the summary judgement of noninfringement.

Takeaway:

- Functional claim language matters even for apparatus claims. When an apparatus claim depends on functioning claim to describe the apparatus, what the device does and how it does it are relevant to understanding what the device is.

- In order to obtain broad coverage of functional claim language, the specification should include several embodiments and figures describing broad functional coverage.

Functional Limitation, Claim Construction, and Obviousness: Bayer v. Mylan

| September 24, 2025

BAYER PHARMA AKTIENGESELLSCHAFT, v. MYLAN PHARMACEUTICALS INC., TEVA PHARMACEUTICALS USA, INC., INVAGEN PHARMACEUTICALS INC.

Date of Decision: September 23, 2025

Before: MOORE, Chief Judge, CUNNINGHAM, Circuit Judge, and SCARSI, District Judge.

Summary

The Federal Circuit affirmed in part, vacated in part, and remanded the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s decision invalidating claims of Bayer Pharma AG’s patent. The court upheld the invalidation of claims 1-4 but vacated and remanded with respect to claims 5-8.

Background

Bayer owns the ’310 patent (U.S. Patent No. 10,828,310), which claims methods for reducing the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and/or peripheral artery disease (PAD) through administration of rivaroxaban and aspirin.

Independent claim 1 recites administration of rivaroxaban and aspirin in clinically proven amounts. Independent claim 5 recites once-daily administration of a first product comprising rivaroxaban and aspirin and a second product comprising rivaroxaban. Claims 1 and 5 are listed below with emphasis added:

1. A method of reducing the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke or cardiovascular death in a human patient with coronary artery disease and/or peripheral artery disease, comprising administering to the human patient rivaroxaban and aspirin in amounts that are clinically proven effective in reducing the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke or cardiovascular death in a human patient with coronary artery disease and/or peripheral arterial dis-ease, wherein rivaroxaban is administered in an amount of 2.5 mg twice daily and aspirin is administered in an amount of 75-100 mg daily.

5. A method of reducing the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke or cardiovascular death in a human patient with coronary artery disease and/or peripheral artery disease, the method comprising administering to the human patient rivaroxaban and aspirin in amounts that are clinically proven effective in reducing the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke or cardiovascular death in a human patient with coronary artery disease and/or peripheral arterial disease, wherein the method comprises once daily administration of a first product comprising rivaroxaban and aspirin and a second product comprising rivaroxaban, and further wherein the first product comprises 2.5 mg rivaroxaban and 75-100 mg aspirin and the second product comprises 2.5 mg rivaroxaban.

Mylan, Teva, and InvaGen filed substantively identical IPR petitions, arguing that a 2016 journal article by Foley (summarizing a trial which includes its dosing regimen of 2.5 mg rivaroxaban twice daily and 100 mg aspirin once daily without disclosing the trial results) and a 2014 journal article by Plosker (disclosing a dosing regimen of 2.5 mg rivaroxaban twice daily, co-administered with 75-100 mg aspirin) anticipated or rendered the claims obvious. The Board agreed and held all challenged claims unpatentable. Bayer appealed.

Discussion

The Federal Circuit addressed four disputes.

The first dispute is related to the phrase “clinically proven effective.” The Board had treated it as non-limiting or inherently anticipated. Bayer argued that the phrase should operate as a substantive limitation on the claims. According to Bayer, the language required that the claimed dosages of rivaroxaban and aspirin be supported by actual clinical trial evidence of efficacy, which in turn distinguished the claims from prior art references such as Foley. Bayer emphasized that Foley disclosed dosing regimens but did not provide trial results demonstrating that the regimens were effective and therefore could not anticipate or render the claimed methods obvious.

The Federal Circuit rejected this position, explaining that it did not decide whether the phrase “clinically proven effective” was a limiting element in claims 1-8. Even assuming it was limiting, the court reasoned that the phrase would not affect patentability because it merely described a characteristic of the treatment regimen rather than altering the steps of the claimed method. The court emphasized that the claims already specify the exact dosages of rivaroxaban and aspirin to be administered, and those dosages remain unchanged regardless of whether clinical trials later demonstrate efficacy. Accordingly, the limitation was deemed functionally unrelated to the claimed method and insufficient to distinguish the claims from the prior art.

The second dispute concerned the proper construction of the phrase “first product comprising rivaroxaban and aspirin” in claim 5. The Board had construed this language broadly to encompass circumstances where rivaroxaban and aspirin were provided in separate dosage forms and administered together, not limited to a single dosage form, and, if administered separately, the dosage forms could be administered simultaneously or sequentially.

The Federal Circuit disagreed with that interpretation. Relying on both the plain language of the claim and the description in the specification, the court concluded that “a first product comprising rivaroxaban and aspirin” required a single dosage form containing both ingredients. The court emphasized that the specification describes that “combination therapy may be administered using separate dosage forms for rivaroxaban and aspirin, or using a combination dosage form containing both rivaroxaban and aspirin.” The court agreed with Bayer that “first product comprising rivaroxaban and aspirin” corresponds to the latter, which narrows the term.

Therefore, the Federal Circuit remanded for further consideration so that the Board’s analysis of the obviousness arguments would be under the correct construction of the “first product” term.

The third dispute concerned whether the Board adequately explained a skilled artisan’s motivation to combine the prior art references with a reasonable expectation of success. The Federal Circuit agreed with the Board’s decision and found it supported by substantial evidence. The court noted that the Board identified both an overlap in the disclosed dosage ranges and the established practice of administering aspirin within that range. The court further found that Foley and Plosker described similar motivations for combining rivaroxaban with aspirin in patients with cardiovascular risk, which supported the Board’s conclusion that a skilled artisan would have had reason to combine the references with a reasonable expectation of success. Accordingly, the Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s determination of obviousness as to dependent claims 3-4 and 6-7.

The fourth dispute concerned Bayer’s argument that its own clinical trial provided clinical proof of efficacy was an unexpected result. The Federal Circuit rejected this position, holding that there was no nexus between the asserted unexpected property and the claimed invention. The court explained that the asserted results were tied only to the “clinically proven effective” limitation, which it had already deemed functionally unrelated to the actual treatment method. Without that nexus, the secondary consideration of unexpected results could not support nonobviousness.

Takeaways

- Claim language that merely recites a property or result, without further defining the claimed steps or structure, may be deemed functionally unrelated and insufficient to establish distinction over the prior art.

- Secondary considerations require a demonstrated nexus between the evidence presented and the claimed invention as construed.

The Federal Circuit’s First AIA Derivation Case

| September 10, 2025

Global Health Solutions LLC v. Selner

Date of Decision: August 26, 2025

Before: Stoll, Stark, Circuit Judges. Goldberg, District Judge.

Summary:

The Federal Circuit addressed a derivation proceeding under the AIA for the first time. While derivation issues arose in pre-AIA interference proceedings, AIA derivation does not require a showing of who is first-to-conceive. Independent conception by an accused inventor overcomes the derivation accusation.

Procedural History:

Global Health Solutions (GHS) petitioned for an AIA derivation proceeding against Selner. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“Board”) granted the petition because GHS identified at least one claim in GHS’ application that is (i) the same or substantially the same as Selner’s claimed invention and is also (ii) the same or substantially the same as the invention disclosed to Selner. After the derivation proceedings, the Board ruled in Selner’s favor. GHS appealed to the Federal Circuit.

Background:

In 2013, Selner and Burnam worked together, although unsuccessfully, to make and sell a novel emulsifier-free wound treatment ointment. Burnam later left and formed GHS. GHS and Selner each filed a patent application on a wound treatment ointment and method for making it, resulting in permanently suspended nanodroplets without the use of an emulsifier that can irritate a patient’s skin. Selner is the first-filer, and GHS is the second-filer. An AIA derivation proceeding provides a limited opportunity for a first-inventor second-filer to obtain a patent despite another person filing an application first (first-filer) in the situation where the first filer derived the invention from the second-filer. During the derivation proceedings, the Board found that Burnam conceived the invention and communicated it to Selner, but the Board also found that Selner proved conception earlier the same day Burnam contacted him.

Decision:

Pre-AIA case law involving derivation often arose in the context of an interference to determine who was the first to invent under the previous first-to-invent law. However, when the AIA eliminated interferences and transformed 35 USC 135 from a law governing interferences to one governing derivation proceedings, Congress did not specify what a second-filer inventor must prove to show that the first-filer inventor derived the claimed invention from the second-filer inventor. However, the court concludes that “the required elements of a derivation claim have not changed other than to the extent necessary to reflect the transition from a first-to-invent to a first-to-file system of patent administration.”

Derivation in an AIA case requires the petitioner to “produce evidence sufficient to show (i) conception of the claimed invention, and (ii) communication of the conceived invention to the respondent prior to respondent’s filing of that patent application.” In a footnote, the Court sidestepped any decision regarding whether a party’s burden of proof in an AIA derivation proceeding is by a preponderance of evidence or by clear and convincing evidence (in pre-AIA interferences, proof of derivation was by clear and convincing evidence) since neither party raised this issue. But, a “respondent can overcome the petitioner’s showing by proving independent conception prior to having received the relevant communication from the petitioner.”

In particular, Selner need not prove that he was the first-to-conceive. Although the Board erred in focusing on whether Selner or Burnam was the first-to-invent or first-to-conceive, that was harmless error. “[A] first-to-file respondent like Selner need only prove that his conception was independent.” While the Board erroneously reached its decisions predicated on Selner being the first-to-conceive, the Board, in doing so, also indirectly determined that Selner independently conceived, and therefore, did not derive his invention from Burnam.

GHS argued that the Board erred by not requiring Selner to corroborate his inventorship with evidence independent of himself. The court found no such error. First, a “rule of reason test is used to determine whether an alleged inventor’s testimony is sufficiently corroborated.” Second, “the Board must consider ‘all pertinent evidence’ and then determine whether the ‘inventor’s story’ is credible.” More importantly, “[d]ocumentary or physical evidence that is made contemporaneously with the inventive process provides the most reliable proof that the inventor’s testimony has been corroborated.” Here, the corroboration was achieved through emails retrieved by Selner’s attorney’s law clerk from Selner’s AOL email account that were generated contemporaneously with the inventive process. And, such emails, whose authenticity was not challenged by GHS, do not require independent corroboration. In addition, the metadata generated by the web-based email server is independent of Selner’s own testimony and documents. Accordingly, the Board had substantial evidence for its findings of fact and there was no reversible error.

GHS argued that Selner did not show reduction to practice to prove conception. The court agreed with the Board that conception can occur without reducing the invention to practice. “Selner’s conception was complete at the point at which he was ‘able to define [the Invention] by its method of preparation’ or when he had formed ‘a definite and permanent idea of the complete and operative invention.’”

GHS argued that Burnam should be named as a co-inventor on Selner’s application. The court refused because GHS did not properly present this request to the Board and is thus forfeited. 37 CFR 42.22 requires a contested request for correction of inventorship in a patent application to be made in a separate motion, including a “statement of the precise relief requested” and a “full statement of the reasons for the relief requested, including a detailed explanation of the significance of the evidence including material facts, and the governing law, rules, and precedent.” No such separate motion was made to the Board, nor was any detailed explanation supporting joint inventorship and material facts relating thereto provided.

Takeaways:

In this case, even though the second-filer showed conception and communication of the invention to the first-filer, the first-filer’s independent conception was a complete defense over the derivation accusation. Unfortunately for Burnam (because GHS did not file a separate motion for correcting inventorship in Selner’s application), the “independent” nature of Selner’s conception was never really challenged despite all the interactions between him and Selner.

This case also provided good reminders that reduction to practice is not required for showing conception, and that contemporaneously generated evidence can corroborate the inventor’s story.

| August 27, 2025

Presumption of Validity Does Not Protect a Patent from Invalidity for Lack of Adequate Written Description

Case Name: MONDIS TECHNOLOGY LTD. v. LG ELECTRONICS INC.

Decided: August 8, 2025 (Precedential)

Panel: Taranto, Clevenger, and Hughes, Circuit Judges

Summary

The CAFC held that Mondis’s patent is invalid for lack of adequate written description for a claim limitation introduced by amendment to overcome a prior art rejection during prosecution, where the prosecution history itself clearly suggested a lack of written description so that Mondis could not rely solely on the presumption of validity; expert testimony on infringement issues did not provide substantive evidence of validity; and although the amendment was allowed by the Examiner, allowance alone did not prove written description compliance, where the prosecution history indicated contrary.

Details

Mondis owns U.S. Patent No. 7,475,180. The ’180 patent basically describes a technology using matching of identification information to prevent unauthorized control of a display unit by an external computer sending video signals to the display unit. For example, the patent’s specification describes an embodiment where one or more ID numbers are stored in the display unit’s database and the external computer is assigned a unique ID number. The computer’s ID number is compared against the display unit’s database and the computer is allowed to control the display unit only when there is a match between the ID numbers.

As originally filed, the underlying application recited the following claim language:

…

a memory in which at least display unit information is stored, said display unit information including an identification number for identifying said display unit and characteristic information of said display unit; and … .

During prosecution, the above claim language was amended by the applicant adding a phrase “at least a type of” to overcome an art-based rejection, to read:

…

a memory in which at least display unit information is stored, said display unit information including an identification number for identifying at least a type of said display unit and characteristic information of said display unit; and

… .

The Examiner allowed the application over the prior art in response to the amendment, including the above claim language—referred to as “the type limitation”—which is set forth in claim 14 of the resulting patent. The prosecution record includes the Examiner’s Interview Summary stating that the above amendment was proposed by the applicant during the interview so as “to more clearly specify identification number as a ‘type’ of display unit which examiner agree[d] will read over the previous art applied regarding … the claims.”

Mondis sued LG for infringement of the ’180 patent. In the district court proceeding, LG challenged the patent’s claim 14 and its dependent claim 15 as invalid for lacking written description for the type limitation. The jury determined that the ’180 patent was not proven invalid and was infringed by that LG’s accused products. Both parties appealed—Mondis dissatisfied with the district court vacating an original damages verdict and ordering retrial leading to a reduced damages award, and LG contesting the district court’s denial of its motion for judgment as a matter of law (JMOL) of invalidity and infringement, among other issues.

At issue on appeal is whether the type limitation complies with the written description requirement of 35 U.S.C. § 112, ¶ 1. The CAFC noted that the written description requirement is a question of fact, reviewed for substantial evidence. “Patents are presumed to be valid and overcoming this presumption requires clear and convincing evidence,” and the burden of persuasion was on LG.

Mondis conceded that there is no express support for the type limitation in the patent. Mondis’s main arguments were: (A) the presumption of validity frees it from the requirement to produce evidence of adequate written description support, and (B) substantial evidence of validity is provided by each of (B-1) Mondis’s expert testimony, (B-2) LG’s expert’s admissions, and (B-3) the patent’s prosecution history. The CAFC rejected each argument.

As to (A) the presumption of validity argument, the CAFC noted that some patents are “presumed valid at birth [such that] a patentee need submit no evidencein support of a conclusion of validity,” whereas others are themselves “clear enough that [the patent specification] establishes inadequacy of support in the written description for the full scope of the claimed invention unless there is contrary evidence.” The CAFC found that the ’180 patent falls under the second category, where the prosecution history made clear that the addition of the type limitation to overcome the art rejection changed the nature of the claimed ID number from one identifying a specific display unit to one identifying a type of display unit.

As to (B-1) Mondis’s expert testimony, the expert presented an infringement theory pointing to the patent’s disclosure of an embodiment where an ID number is sent from the display to a computer:

Namely, an ID number is sent to the computer 1 from the display device 6 so that the computer 1 identifies that the display device 6 having a communication function is connected and the computer 1 compares the ID number with the ID number registered in the computer 1.

The Mondis’s expert explained to the jury that the above passage to mean that “the communication function [disclosed in the specification] is an actual video format [such that] the ID number is defining what video format the display is capable of receiving.”

The CAFC noted that the above testimony was “about infringement rather than validity,” and that the plain words of the specification, read in the context of the surrounding disclosure, would convey that the patent discloses a specific display unit, as opposed to a specific type of display unit.

As to (B-2) LG’s expert’s admissions, Mondis asserted that LG’s noninfringement testimony provides substantial evidence that serial numbers could be used to identify a particular display unit, and could hypothetically be a type ID.

The CAFC noted that to meet the written description requirement, “it is the specification itself that must demonstrate possession.” Nothing in the patent specification describes a serial number that identifies any type of display unit, and the expert testimony—which was again about infringement rather than validity—does not address whether a skilled artisan would find support in the specification for the type limitation.

As to (B-3) the patent’s prosecution history, Mondis argued that the fact that the claim amendment was entered without objection led to “an especially weighty presumption of correctness,” citing Commonwealth Sci. & Indus. Rsch. Org. v. Buffalo Tech., Inc. (USA), 542 F.3d 1363, 1380 (Fed. Cir. 2008). That is, Modis argued that “when the examiners allowed the amendment, they agreed to the type limitation because they understood that it was supported by written description.”

The CAFC clarified that Commonwealth Science, while finding a “presumption of validity based on the PTO’s issuance of the patent despite the amendments,” “does not hold that the examiner’s allowance of claims by itself provides substantial evidence that the claims comply with the requirements of § 112.” “If it did, there would rarely be a situation where an issued patent could later be invalidated for lack of written description.”

Further, the CAFC pointed to the Examiner’s interview summary explaining the nature of the claim amendment as overcoming the art rejection, but silent as to whether the Examiner considered compliance with the written description requirement. As such, the prosecution history fell short of substantial evidence.

Takeaways

This case provides a reminder that allowance of claim amendments and presumption of validity of patents alone do not constitute substantial evidence that the claims comply with the written description requirement. Care should be taken when adding a claim limitation that is not expressly supported by the specification, even if the amendment would successfully overcome an art-based rejection.

| August 13, 2025

Shocking-Applicant Admitted Prior Art Sinks Own Patent

Case Name: SHOCKWAVE MEDICAL, INC. v. CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEMS, INC.

Decided: July 14, 2025

Before: LOURIE, DYK, and CUNNINGHAM, opinion by DYK

Background

Shockwave owns US patent no. 8,956,371 directed to treatment of atherosclerosis through intravascular lithotripsy. Lithotripsy is a technique used to break up kidney stones by using shockwaves induced by plasma. Atherosclerosis is a buildup of fatty deposits in blood vessels. Balloon angioplasty is a method of treating atherosclerosis by guiding a balloon catheter to the location of a blood vessel containing calcified plaque buildup.

Shockwave’s claimed device uses a typical over-the-wire angioplasty balloon catheter and adds electrodes within a fluid-filled balloon with a pulse generator to generate shockwaves to break up calcified plaque deposits. Claims 1 and 5 state:

1. An angioplasty catheter comprising: an elongated carrier sized to fit within a blood vessel,

said carrier having a guide wire lumen extending there through;

an angioplasty balloon located near a distal end of the carrier with a distal end of the balloon being sealed to the carrier near the distal end of the carrier and with a proximal end of the balloon defining an annular channel arranged to receive a fluid therein that inflates the balloon; and

an arc generator including a pair of electrodes, said electrodes being positioned within and in non-touching relation to the balloon,

said arc generator generating a high voltage pulse sufficient to create a plasma arc between the electrodes resulting in a mechanical shock wave within the balloon that is conducted through the fluid and through the balloon and wherein the balloon is arranged to remain intact during the formation of the shockwave.

5. The catheter of claim 2, wherein the pair of electrodes is disposed adjacent to and outside of the guide wire lumen.

Claim 2 requires that the “pair of electrodes” include a “pair of metallic electrodes.

CSI filed an inter partes review (IPR) petition challenging all claims of Shockwave’s ‘371 patent as obvious over EP 0571306 to Levy. The EP patent describes using laser-generated pulses to disintegrate plaque in blood vessels. CSI’s petition pointed to Shockwave’s ‘371 patent disclosure discussing “typical prior art over-the-wire angioplasty balloon catheter[s] … [that] are usually non-compliant with a fixed maximum dimension when expanded with a fluid such as saline.” The petition argued that it would have been obvious to modify Levy with the well-known angioplasty balloon catheter disclosed by the applicant admitted prior art (AAPA). (Keep in mind that a rejection in an IPR petition can only be based on patents and printed publications).

The Patent Trian and Appeal Board (PTAB) issued a final decision finding claims 1-4 and 6-17 were unpatentable as obvious. The PTAB stated that AAPA qualified as “prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.” After the decision, the USPTO issued “AAPA Guidance” stating that AAPA is not “prior art consisting of patents or printed publications.” The PTAB thereafter initiated rehearing, relying on AAPA only as evidence of the background knowledge in the art to typical over-the-wire balloon catheters. The PTAB then again concluded that claims 1-4 and 6-17 had been shown to be unpatentable as obvious.

Shockwave appealed the finding of unpatentability while CSI appealed the finding that claim 5 was not unpatentable.

Discussion

AAPA as a basis vs. evidence in an IPR petition

Shockwave argued that both CSI and the PTAB improperly relied on AAPA as a basis for the IPR petition. As set forth in 35 U.S.C. 311(b), a petitioner in an inter partes review may request to cancel as unpatentable 1 or more claims of a patent only on a ground that could be raised under section 102 or 103 and only on the basis of prior art consisting of patents and printed publications. The Federal Circuit has explained that “[a]lthough the prior art that can be considered in [IPRs] is limited to patents and printed publications, it does not follow that we ignore the skilled artisan’s knowledge when determining whether it would have been obvious to modify the prior art.” Koninklijke Philips N.V. v. Google LLC, 948 F.3d 1330, 1337 (Fed. Cir. 2020). This is because the obviousness analysis “requires an assessment of the . . . ‘background knowledge possessed by a person having ordinary skill in the art.’” Dow Jones & Co. v. Ablaise Ltd., 606 F.3d 1338, 1349 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (quoting KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex, Inc., 550 U.S. 398, 401 (2007)).

As set forth in Qualcomm Incorporated v. Apple Inc., 24 F.4th 1367 (Fed. Cir. 2022) (“Qualcomm I”), AAPA can be used as evidence of background knowledge of an ordinarily skilled artisan, but that AAPA cannot be the “basis” of a ground in an IPR petition. Shockwave had noted that the PTAB’s written decision included a table with a column labeled Relevance/Basis to assert that the AAPA was the basis of the ground of rejection. The CAFC, however, distinguished the reference to “basis” by noting that it is an IPR petitioner, not the PTAB, that must comply with what defines the metes and bounds of an IPR. Here, CSI properly relied on general background knowledge to supply missing claim limitations and used AAPA as evidence of that general background in the IPR petition. As such, the IPR petition did not violate section 311(b).

Claim construction of “angioplasty balloon”

Shockwave argues that the Board erred in denying its construction for “angioplasty balloon” as “a balloon that displaces the plaque into the vessel wall to expand the lumen of the vessel” and adopting CSI’s construction of the term as “an inflatable sac that is configured to be inserted into a blood vessel for use in a medical procedure to widen narrowed or obstructed blood vessels.” This argument was dismissed because there is nothing in the language of the claims or specification which supports requiring that an angioplasty balloon press plaque into the vessel wall.

Challenge to Fact Findings

Shockwave challenges three of the PTAB’s fact findings: (1) that an ordinarily skilled artisan would have been motivated to incorporate Levy’s shockwave system into the over-the-wire balloon catheter, (2) that Levy discloses shockwaves, and (3) that Shockwave’s secondary considerations evidence did not outweigh CSI’s obviousness showing. The standard of review for fact findings is substantial evidence. The CAFC found that substantial evidence supports each of the findings.

CSI’s Cross-Appeal

CSI cross-appeals the PTAB’s conclusion that claim 5 had not been shown to be unpatentable as obvious over Levy implemented in an over-the-wire balloon catheter in view of Uchiyama. The PTAB found that the prior art combination did not disclose claim 5’s limitation relating to the placement of electrodes.

Initially, Shockwave argued that CSI lacks Article III standing. As we have discussed in other decisions related to Article III standing, a party does not need Article III standing to receive a PTAB decision, but does need Article III standing to seek review of a PTAB decision. Parties seeking relief before the CAFC have the burden of establishing the existence of an Article III case or controversy. Regarding this, when a party challenging an IPR decision “relies on potential infringement liability as a basis for injury in fact, but is not currently engaging in infringing activity, it must establish that it has concrete plans for future activity that creates a substantial risk of future infringement or would likely cause the patentee to assert a claim of infringement.” Gen. Elec. Co. v. Raytheon Techs. Corp., 983 F.3d 1334, 1341 (Fed. Cir. 2020) (quoting JTEKT Corp. v. GKN Auto, LTD., 898 F.3d 1217, 1221 (Fed. Cir. 2018)).

CSI says it has standing because it has developed an intravascular lithotripsy (IVL) device, and Shockwave’s President publicly commented that the company would aggressively assert claim 5:

We are very pleased that the [Board] validated claim 5 of our ’371 patent, which protects the broad embodiment of our IVL technologies. Specifically, claim 5 describes a device that is delivered over a guidewire and generates shockwaves with electrodes inside of a balloon catheter. We believe that any viable, much less commercially viable, IVL device must contain these elements[.] . . . We believe that our robust portfolio of 40 issued U.S. patents and 50 issued foreign patents captures and protects the truly unique and sophisticated IVL technology[.]

The CAFC found that CSI’s circumstances had constituted sufficiently concrete plans coupled with a substantial likelihood of a suit of infringement of claim 5. Shockwave’s President’s statement reflected the company’s view of claim 5 as reading broadly on IVL technology, and that CSI had sufficiently shown that it was engaging in activity that creates a substantial risk of future infringement to likely cause the patentee to assert infringement.

Regarding obviousness of claim 5, the CAFC found that the PTAB’s analysis was predicated on the teaching of a prior art reference Uchiyama alone as not disclosing electrodes positioned adjacent to and outside of the guidewire lumen. The standard of obviousness requires consideration of the prior art combination as a whole (that is, the combination of Levy with Uchiyama). CSI’s expert had testified that it would have been obvious to implement the features of Uchiyama as a routine design choice. Shockwave did not present contrary evidence. Since there was no evidence in the record supporting the finding as to claim 5, the PTAB is reversed.

Takeaways

- Avoid having an admission of prior art in your specification. If there is prior art disclosing a certain aspect that serves as a background of the invention, refer to that prior art itself instead of creating an admission.

- AAPA cannot be used as a basis of an IPR petition, but can be used as evidence of the state of art.

- Advise your clients to refrain from making statements following a PTAB decision. The President’s statement allowed CSI to establish standing to file the cross appeal which ultimately struck down the last standing claim.

- Expert testimony is important in any IPR petition. CSI had expert testimony regarding obviousness of claim 5 which was not refuted by testimony from Shockwave.

No Going Back!

| July 30, 2025

Eye Therapies, LLC v. Slayback Pharma, LLC (Precedential)

Date of Decision: June 30, 2025

Before TARANTO and STOLL, Circuit Judges, and SCARSI, District Judge. Opinion drafted by SCARSI, District Judge.

Summary:

Eye Therapies appeals from a final written decision of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (the “Board”) holding all claims of U.S. Patent No. 8,293,742 (“the ’742 patent”) unpatentable. Eye Therapies challenges (1) the Board’s construction of the phrase “consisting essentially of” and (2) the Board’s conclusion that all claims of the ’742 patent would have been obvious over the prior art. For reasons explained below, the CAFC reversed the Board’s claim construction of the “consisting essentially of” limitation, vacate its obviousness finding, and remand for further proceedings. The first challenged by Eye Therapies will be discussed in detail.