“Built Tough”: Ford’s Design Patents Survive Creative Attacks by Accused Infringers

| August 21, 2019

Automotive Body Parts Association v. Ford Global Technologies, LLC

July 23, 2019

Before Hughes, Schall, and Stoll

Summary

The Federal Circuit is asked to decide two questions: what types of functionality invalidate a design patent, and whether the same rules of patent exhaustion and repair rights that apply to utility patents ought to also be applied to design patents. On the former, the Federal Circuit decides that “mechanical or utilitarian” functionality, rather than “aesthetic functionality”, invalidates a design patent. On the latter, however unique design patents are from utility patents, the Federal Circuit declines to apply the well-established rules of patent exhaustion and right to repairs differently between design and utility patents.

Details

Ford Motor Company introduced the F-150 pickup trucks in the 1970’s, and the trucks have become a mainstay of Ford’s lineup. The trucks’ popularity has endured, as the model is now in its thirteenth generation, with Ford claiming to have sold more than 1 million F-150 trucks in 2018.

Ford Global Technologies, LLC (“Ford”) is a subsidiary of Ford Motor Company, and manages the parent company’s intellectual property. Ford’s large patent portfolio includes numerous design patents covering different design elements of Ford vehicles. Among those design patents are U.S. Design Patent Nos. D489,299 and D501,685.

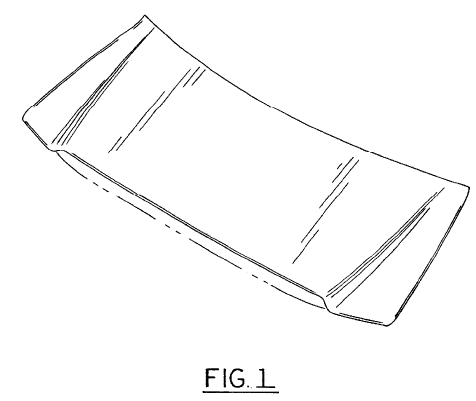

The D’299 patent is directed to an “exterior vehicle hood” having the following design:

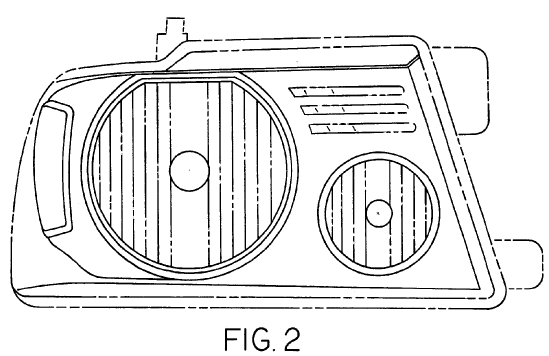

The D’685 patent is directed to a “vehicle head lamp” having the following design:

The patented designs are found on the eleventh generation F-150 trucks, which were in production from 2004 to 2008:

Automotive Body Parts Association (“Automotive Body”) is an association of companies that distribute automotive body parts. The member companies serve predominantly the collision repair industry, selling replacement auto parts to collision repair shops or directly to vehicle owners.

Ford began asserting the D’299 and D’685 patents against Automotive Body in 2005, when Ford initiated a patent infringement action in the International Trade Commission. The ITC action was ultimately settled, followed by a few years of relative quiet until 2013, when tension grew after a member of Automotive Body began selling replacement parts covered by Ford’s two design patents.

In 2013, Automotive Body, together with the member company, initiated a declaratory judgment action in a district court, seeking to have the D’299 and D’685 patents declared invalid, or if valid, unenforceable. Automotive Body moved the district court for summary judgment of invalidity and unenforceability, but was denied. Automotive Body’s appeal of that denial of summary judgment leads us to this decision by the Federal Circuit.

Automotive Body’s arguments on appeal mirror those made in the district court.

- Invalidity

Automotive Body makes two main invalidity arguments. First, the designs of Ford’s two patents are “dictated by function”, and second, the two designs are not a “matter of concern”.

The “dictated by function” argument involves a basic design patent concept: if an article has to be designed a certain way for the article to function, then the design cannot be the subject of a design patent.

Design patents protect only “new, original and ornamental design[s] for an article of manufacture”. 35 U.S.C. 171(a). To be “ornamental”, a particular design must not be essential to the use of the article.

Automotive Body argues, rather creatively, that the designs of Ford’s headlamp and hood are functionally dictated not only by the physical fit on a F-150 truck, but also by the aesthetics of the surrounding body parts. Automotive Body’s position is that these commercial requirements for aesthetic continuity, driven by customer preferences, render Ford’s designs functional.

The Federal Circuit disagrees:

We hold that, even in this context of a consumer preference for a particular design to match other parts of a whole, the aesthetic appeal of a design to consumers is inadequate to render that design functional…If customers prefer the “peculiar or distinctive appearance” of Ford’s designs over that of other designs that perform the same mechanical or utilitarian functions, that is exactly the type of market advantage “manifestly contemplate[d]” by Congress in the laws authorizing design patents.

In other words, functionality that invalidates a design should be “mechanical or utilitarian”, and not aesthetical.

Particularly damaging to Automotive Body’s argument is Ford’s abundant evidence of “performance parts”, that is, alternative headlamp and hood designs that would also fit the F-150 trucks. As the Federal Circuit explains, “the existence of ‘several ways to achieve the function of an article of manufacture,’ though not dispositive, increases the likelihood that a design serves a primarily ornamental purpose.”

To bolster its functionality argument, Automotive Body attempts to borrow the doctrine of “aesthetic functionality” from trademark law.

Under that doctrine, trademark protection is unavailable to features that serve an aesthetic function that is independent and distinct from the function of source identification. For example, “John Deere green”, the color, may invoke an immediate association with John Deere, the brand, but the color itself also serves the significant nontrademark function of color-matching many farm equipment. As such, the color is not entitled to trademark protection.[1]

The Federal Circuit quickly disposes of Automotive Body’s “aesthetic functionality” argument, finding that the doctrine rooted in trademark law does not apply to patent law. The competitive considerations driving the “aesthetic functionality” doctrine of trademark law do not apply to the anticompetitive effects of design patents.

Automotive Body’s second invalidity argument is that the designs of Ford’s two patents are not a “matter of concern”.

The “matter of concern” argument involves the straightforward concept that, if no one cares about a particular design, then that design is not deserving of patent protection. Automotive Body argues that Ford’s patented headlamp and hood designs are not a “matter of concern”, because an F-150 owner in need of a replacement headlamp or hood would assess the replacement part simply for their aesthetic compatibility with the truck.

The Federal Circuit finds two faults with Automotive Body’s arguments. First, that an F-150 owner would assess the aesthetic of a headlamp or hood design means that, by definition, the designs are a matter of concern. Second, Automotive Body errs in temporally limiting the “matter of concern” inquiry to when a consumer is purchasing a replacement part. The proper inquiry is “whether at some point in the life of the article an occasion (or occasions) arises when the appearance of the article becomes a ‘matter of concern’”.

- Unenforceability

Automotive Body’s unenforceability arguments are also two-fold.

First, Automotive Body argues that under the doctrine of patent exhaustion, the authorized sale of an F-150 truck exhausts all design patents embodied in the truck. This exhaustion therefore permits the use of Ford’s designs on replacement parts intended for use with the truck.

The Federal Circuit disagrees that the doctrine of patent exhaustion should be so broadly applied.

The doctrine of patent exhaustion is triggered only if the sale is authorized, and conveys only with the article sold. Since Ford has not authorized Automotive Body’s sales of replacement headlamps and hood, and Automotive Body is not a purchaser of Ford’s F-150 trucks, the Federal Circuit easily concludes that Automotive Body cannot rely on patent exhaustion as a defense.

Automotive Body’s second argument is that an authorized sale of the F-150 truck also conveys to the owner the right to repair, so that the owner of the F-150 truck would be permitted to replace the headlamps or hood on the truck.

Here also, the Federal Circuit disagrees with Automotive Body’s broad application of the right to repair.

The right to repair allows an owner to repair the patented headlamps or hood on the truck, but does not allow the owner to make new copies of the patented designs.

A common premise of Automotive Body’s unenforceability arguments is their broad interpretation of the term “article of manufacture” as used in the statute. From Automotive Body’s perspective, the term includes not only the patented component, but also the larger product incorporating that component. By this interpretation, the sale of either the patented headlamps or hood, or the truck containing the patented headlamps or hood would totally exhaust Ford’s rights in the design patents.

The Federal Circuit rejects Automotive Body’s broad interpretation:

In our view, the breadth of the term “article of manufacture” simply means that Ford could properly have claimed its designs as applied to the entire F-150 or as applied to the hood and headlamp… Unfortunately for ABPA, Ford did not do so; the designs for Ford’s hood and headlamp are covered by distinct patents, and to make and use those designs without Ford’s authorization is to infringe.

Had Ford’s design patents covered the whole F-150 truck, the sale of the truck would have exhausted Ford’s rights in those patents. But, as it were, Ford’s patents cover only the designs of the headlamps and the hood, and not the design for the truck as a whole. As such, while the authorized sale of an F-150 truck permits the owner to use and repair the headlamps and the hood, the sale leaves untouched Ford’s ability to prevent the owner from making new copies of those designs.

It is not uncommon for aftermarket suppliers, especially those who supply parts intended to restore a vehicle to its original condition and aesthetics, to promise identity or near identity between its products and the OEM parts. This promise, however, would effectively be an admission that the products infringe any design patents covering the part. In this respect, this Federal Circuit decision may signal a tough road ahead for aftermarket suppliers.

Takeaway

- Use design patents not only to protect a product as a whole, but also to protect the smallest sellable component of the product.

[1] Interestingly, a district court recently determined that trademark protection extended to the combination of “John Deere green” and “John Deere yellow” as a color scheme.