APPLE MAKES ROTTEN CONVINCING THAT THE PTAB CANNOT CONSTRUE CLAIMS PROPERLY

| April 7, 2022

Apple, Inc vs MPH Technologies, OY

Decided: March 9, 2022

MOORE, Chief Judge, PROST and TARANTO. Opinion by Moore.

Summary:

Apple appealed losses on 3 IPRs attempting to convince the CAFC that the PTAB had misconstrued numerous dependent claims for a myriad of reasons. The CAFC sided with the Board on all counts, in general showing deference to the PTAB and its ability to properly interpret claims.

Background:

Apple appealed from 3 IPRs wherein the PTAB had held Apple failed to show claims 2, 4, 9, and 11 of U.S. Patent No. 9,712,494; claims 7–9 of U.S. Patent No. 9,712,502; and claims 3, 5, 10, and 12–16 of U.S. Patent No. 9,838,362 would have been obvious. Apple’s IPR petitions relied primarily on a combination of Request for Comments 3104 (RFC3104) and U.S. Patent No. 7,032,242 (Grabelsky).

The patents disclose a method for secure forwarding of a message from a first computer to a second computer via an intermediate computer in a telecommunication network in a manner that allowed for high speed with maintained security.

The claims of the ’494 and ’362 patents cover the intermediate computer. Claim 1 of the ’494 patent was used as the representative independent claim for the patents:

1. An intermediate computer for secure forwarding of messages in a telecommunication network, comprising:

an intermediate computer configured to connect to a telecommunication network;

the intermediate computer configured to be assigned with a first network address in the telecommunication network;

the intermediate computer configured to receive from a mobile computer a secure message sent to the first network address having an encrypted data payload of a message and a unique identity, the data payload encrypted with a cryptographic key derived from a key exchange protocol;

the intermediate computer configured to read the unique identity from the secure message sent to the first network address; and

the intermediate computer configured to access a translation table, to find a destination address from the translation table using the unique identity, and to securely forward the encrypted data payload to the destination address using a network address of the intermediate computer as a source address of a forwarded message containing the encrypted data payload wherein the intermediate computer does not have the cryptographic key to decrypt the encrypted data payload.

The ’502 patent claims the mobile computer that sends the secure message to the intermediate computer.

Decision:

The Court first looked at dependent claim 11 of the ’494 patent and dependent claim 12 of the ’362 patent requirement that “the source address of the forwarded message is the same as the first network address.”

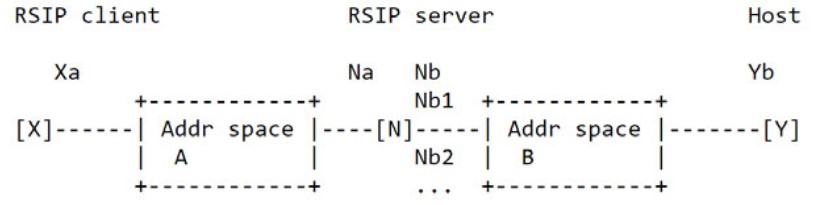

Apple had asserted RFC3104 disclosed this aspect of the claims. Specifically, RFC3104 discloses a model wherein an RSIP server examines a packet sent by Y destined for X. “X and Y belong to different address spaces A and B, respectively, and N is an [intermediate] RSIP server.” N has two addresses: Na on address space A and Nb on address space B, which are different. Apple asserted the message sent from Y to X is received by RSIP server N on the Nb interface and then must be sent to Na before being forwarded to X.

The model topography for RFC3104 is illustrated as:

In light thereof, Apple asserted that because the intermediate computer sends the message from Nb to Na before forwarding it to X, Na is both a first network address and the source address of the forwarded message. That the message was not sent directly to Na, Apple claimed, was of no import given the claim language. The Board had disagreed and found there was no record evidence that the mobile computer sent the message directly to Na.

In the appeal, Apple argued the Board misconstrued the claims to require that the mobile computer send the secure message directly to the intermediate computer. Rather, Apple asserted, the mobile computer need not send the message to the first network address so long as the message is sent there eventually. Specifically, Apple emphasized that the PTAB’s construction is inconsistent with the phrase “intermediate computer configured to receive from a mobile computer a secure message sent to the first network address” in claim 1 of the ’494 patent, upon which claim 11 depends.

The Court construed the plain meaning of “intermediate computer configured to receive from a mobile computer a secure message sent to the first network address” requires the mobile computer to send the message to the first network address. The phrase identifies the sender (i.e., the mobile computer) and the destination (i.e., the first network address). The CAFC maintained that the proximity of the concepts links them together, such that a natural reading of the phrase conveys the mobile computer sends the secure message to the first network address. Thus the CAC agreed with the PTAB that the plain language establishes direct sending.

The Court reenforced their holding by looking to the written description as confirming this plain meaning. Specifically, they noted it describes how the mobile computer forms the secure message with “the destination address . . . of the intermediate computer.” The mobile computer then sends the message to that address. There is no passthrough destination address in the intermediate computer that the secure message is sent to before the first destination address. Accordingly, like the claim language, the written description describes the secure message as sent from the mobile computer directly to the first destination address.

Second, the CAFC examined dependent claim 4 of the ’494 patent is similar to claim 5 of the ’362 patent. Claim 4 of the ‘494 recites:

…wherein the translation table includes two partitions, the first partition containing information fields related to the connection over which the secure message is sent to the first network address, the second partition containing information fields related to the connection over which the forwarded encrypted data payload is sent to the destination address. (emphasis added in opinion).

The Board had interpreted “information fields” in this claim to require “two or more fields.” However, Apple’s obviousness argument relied on Figure 21 of Grabelsky, which disclosed a partition with only a single field. Therefore, the Board found Apple failed to show the combination taught this limitation. Moreover, the Board found Apple failed to show a motivation to modify the combination to use multiple fields.

On claim construction, Apple contended there is a presumption that a plural term covers one or more items. Apple maintained that patentees can overcome that presumption by using a word, like “plurality”, that clearly requires more than one item.

The Court found that Apple misstated the law. In accordance with common English usage, the Court presumes a plural term refers to two or more items. And found that this is simply an application of the general rule that claim terms are usually given their plain and ordinary meaning.

The Court also noted that there is nothing in the written description providing any significance to using a plurality of information fields in a partition. The CAFC therefore found that absent any contrary intrinsic evidence, the Board correctly held that fields referred to more than one field.

Third, the Court looked to Claim 2 of the ’494 patent and claim 3 of the ’362 patent. Claim 2 of the ‘494 states:

…wherein the intermediate computer is further configured to substitute the unique identity read from the secure message with another unique identity prior to forwarding the encrypted data payload. (emphasis added in opinion).

The Board construed the word “substitute” to require “changing or modifying, not merely adding to.” Because it determined that RFC3104 merely involved “adding to” the unique identity, the Board found Apple had failed to show RFC3104 taught this limitation. The Board expressly addressed Apple’s argument from the hearing that “adding the header is the same as replacing the header because at the end of the day you have a different header than what you had before, a completely different header.” The Board disagreed with Apple and construed “substitute” to mean “changing, replacing, or modifying, not merely adding,” and observed that this construction disposed of Apple’s position.

The CAFC found no misconstruction by the PTAB with this interpretation. Moreover, the Court noted tat substantial evidence supports the Board’s finding that Apple failed to show a motivation to modify the prior art combination to include substitution. Apple relied solely on its expert’s contrary testimony, which the Court found the Board had properly disregarded as conclusory.

Fourth, the Court reviewed the PTAB’s interpretation of claim 9 of the ’494 patent, similar to claim 10 of the ’362 patent. Claim 9 of the ‘494 states:

…wherein the intermediate computer is configured to modify the translation table entry address fields in response to a signaling message sent from the mobile computer when the mobile computer changes its address such that the intermediate computer can know that the address of the mobile computer is changed. (emphasis added in opinion).

Apple argued that establishing a secure authorization in RFC3104 includes creating a new table entry address field as required by the claim. The Board disagreed, reasoning that “modify[ing] the translation table entry address fields” requires having existing address fields when the mobile computer changes its address. Accordingly, it found Apple failed to how the combination taught this limitation. Apple argued before the CAFC that the “configured to modify the translation table entry address fields” limitation is purely functional and, thus, covers any embodiment that results in a table with different address fields, including new address fields. The CAFC disagreed, finding as the Board held, the plain meaning of “modify[ing] the translation table entry address fields” requires having existing address fields in the translation table to modify.

Specifically, the Court reasoned that the surrounding language showing the modification occurs “when the mobile computer changes its address such that the intermediate computer can know that the address of the mobile computer is changed” further supports the existence of an address field prior to modification. Thus, the CAFC found that the limitation does not merely claim a result; it recites an operation of the intermediate computer that requires an existing address field.

Fifth and final, the Court reviewed claim 7 of the ’502 patent which recites:

…wherein the computer is configured to send a signaling message to the intermediate computer when the computer changes its address such that the intermediate computer can know that the address of the computer is changed.

The Court noted that the RFC3104 disclosed an ASSIGN_REQUEST_RSIPSEC message that requests an IP address assignment. Apple argued that, when a computer moves to a new address, the computer uses this message as part of establishing a secure connection and, in the process, the intermediate computer knows the address has been changed. The Board had found that the message was not used to signal address changes. Accordingly, the Board determined that Apple had failed to show that the intermediate computer knows that the address is changed, as required by the claim language. Apple reprises its arguments, which the Board had rejected.

The CAFC noted that claims 7–9 of the ’502 patent require a computer to send a message to the intermediate computer “such that the intermediate computer can know that the address of the computer is changed.” The Court affirmed the Board’s contrary finding was supported by substantial evidence, including MPH’s expert testimony and RFC3104 itself. MPH’s expert testified that a skilled artisan would not have understood the relevant disclosure in RFC3104 to teach any signal address changes. Agreeing with the PTAB, the Court found that the relevant disclosure in RFC3104 relates to establishing an RSIP-IPSec session, not to signal address changes. Hence, they saw no reason why the Board was required to equate communicating a new address and signaling an address change. They therefore concluded that substantial evidence supports the Board’s finding.

In the end, the CAFC affirmed all of the Board’s final written decisions holding that claims 2, 4, 9, and 11 of the ’494 patent; claims 7–9 of the ’502 patent; and claims 3, 5, 10, and 12–16 of the ’362 patent would not have been obvious.

Take away:

Although the CAFC reviews claim construction and the Board’s legal conclusions of obviousness de novo, they are inclined toward giving deference to the PTAB. Caution should be taken in attempting to convince the CAFC that the Board has misconstrued claims unless there is a clear showing that the Board did not follow the Phillips standard (Claim terms are given their plain and ordinary meaning, which is the meaning one of ordinary skill in the art would ascribe to a term when read in the context of the claim, specification, and prosecution history).