A Good Fry: Patent on Oil Quality Sensing Technology for Deep Fryers Survives Inter Partes Review

| October 4, 2019

Henny Penny Corporation v. Frymaster LLC

September 12, 2019

Before Lourie, Chen, and Stoll (Opinion by Lourie)

Summary

In an appeal from an inter partes review, the Federal Circuit affirmed the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s decision to uphold the validity of a patent relating to oil quality sensing technology for deep fryers. The Board found, and the Federal Circuit agreed, that the disadvantages of pursuing the challenger’s proposed modification of the prior art weighed against obviousness, in the absence of some articulated rationale as to why a person of ordinary skill in the art would have pursued that modification. In addition, the Federal Circuit reiterated that as a matter of procedure, the scope of an inter partes review is limited to the theories of unpatentability presented in the original petition.

Details

Fries are among the most common deep-fried foods, and McDonald’s fries may still be the most popular and highest-consumed worldwide. But, there would be no McDonald’s fries without a deep fryer and a good pot of oil, and Frymaster LLC (“Frymaster”) is the maker of some of McDonald’s deep fryers.

During deep frying, chemical and thermal interactions between the hot frying oil and the submerged food cause the food to cook. These interactions degrade the quality of the oil. In particular, chemical reactions during frying generate new compounds, including total polar materials (TPM), that can change the oil’s physical properties and electrical conductivity.

Frymaster’s fryers are equipped with integrated oil quality sensors (OQS), which monitor oil quality by measuring the oil’s electrical conductivity as an indicator of the TPM levels in the oil. This sensor technology is embodied in Frymaster’s U.S. Patent No. 8,497,691 (“691 patent”).

The 691 patent describes an oil quality sensor that is integrated directly into the circulation of cooking oil in a deep fryer, and is capable of taking measurements at the deep fryer’s operational temperatures of 150-180°C, i.e., without cooling the hot oil.

Claim 1 of the 691 patent is representative:

1. A system for measuring the state of degradation of cooking oils or fats in a deep fryer comprising:

at least one fryer pot;

a conduit fluidly connected to said at least one fryer pot for transporting cooking oil from said at least one fryer pot and returning the cooking oil back to said at least one fryer pot;

a means for re-circulating said cooking oil to and from said fryer pot; and

a sensor external to said at least on[e] fryer pot and disposed in fluid communication with said conduit to measure an electrical property that is indicative of total polar materials of said cooking oil as the cooking oil flows past said sensor and is returned to said at least one fryer pot;

wherein said conduit comprises a drain pipe that transports oil from said at least one fryer pot and a return pipe that returns oil to said at least one fryer pot,

wherein said return pipe or said drain pipe comprises two portions and said sensor is disposed in an adapter installed between said two portions, and

wherein said adapter has two opposite ends wherein one of said two ends is connected to one of said two portions and the other of said two ends is connected to the other of said two portions.

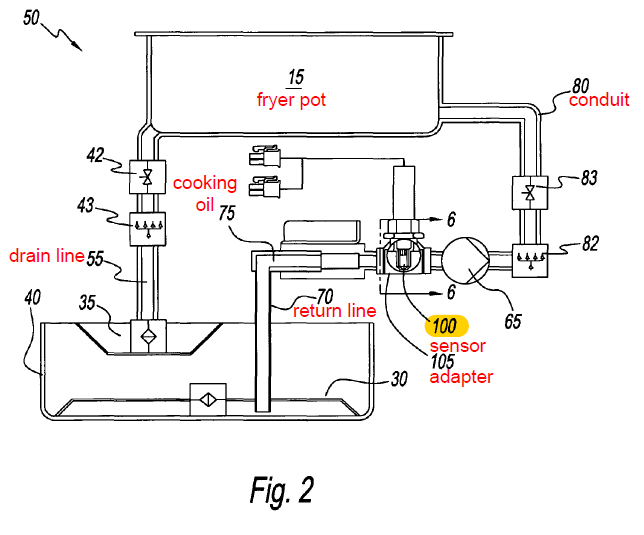

Figure 2 of the 691 patent illustrates the structure of Frymaster’s system:

Henny Penny Corporation (HPC) is a competitor of Frymaster, and initiated an inter partes review of the 691 patent.

In its petition, HPC challenged claim 1 of the 691 patent as being obvious over Kauffman (U.S. Patent No. 5,071,527) in view of Iwaguchi (JP2005-55198).

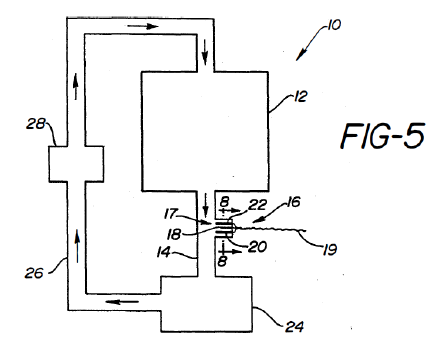

Kauffman taught a system for “complete analysis of used oils, lubricants, and fluids”. The system included an integrated electrode positioned between drain and return lines connected to a fluid reservoir. The electrode measured conductivity and current to monitor antioxidant depletion, oxidation initiator buildup, product buildup, and/or liquid contamination. Kauffman’s system operated at 20-400°C. However, Kauffman did not teach monitoring TPMs.

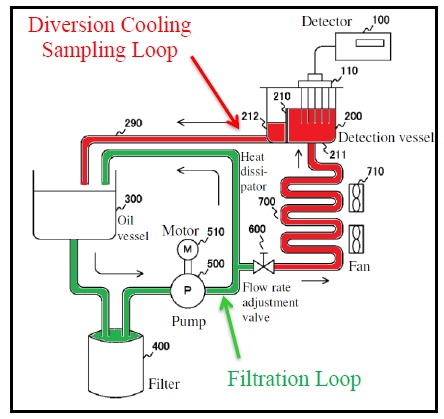

Iwaguchi taught monitoring TPMs to gauge quality of oil in deep fryers. However, Iwaguchi cooled the oil to 40-80°C before taking measurements. If the oil temperature was outside the disclosed range, Iwaguchi’s system would register an error. Specifically, oil was diverted from the frying pot to a heat dissipator where the oil was cooled to the appropriate temperature, and then to a detection vessel where a TPM detector measured the electrical properties of the oil to detect TPMs. Iwaguchi taught that cooling relieved heat stress on the detector, prevented degradation, and obviated the need for large conversion tables.

The parties’ dispute focused on the sensor feature of the 691 patent.

In the initial petition, HPC argued simply that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have found it obvious to modify Kauffman’s system to “include the processor and/or sensor as taught by Iwaguchi.”

In its patent owner’s response, Frymaster disputed HPC’s proposed modification. Frymaster argued that Iwaguchi’s “temperature sensitive” detector would be inoperable in an “integrated” system such as that taught in Kauffman, unless Kauffman’s system was further modified to add an oil diversion and cooling loop. However, such an addition would have been complex, inefficient, and undesirable to those skilled in the art.

In its reply, HPC changed course and argued that it was unnecessary to swap the electrode in Kauffman’s system for Iwaguchi’s detector. HPC argued that Kauffman’s electrode was capable of monitoring TPMs by measuring conductivity, and that Iwaguchi was relevant only for teaching the general desirability of using TPMs to assess oil quality.

However, whereas HPC’s theory of obviousness in its original petition was based on a modification of the physical structure of Kauffman’s system, HPC’s reply proposed changing only the oil quality parameter being measured. During the oral hearing before the Board, HPC’s counsel even admitted to this shift in HPC’s theory of obviousness.

In its final written decision, the Board determined, as a threshold matter of procedure, that HPC impermissibly presented a new theory of obviousness in its reply, and that the patentability of the 691 patent would be assessed only against the grounds asserted in HPC’s original petition.

The Board’s final written decision thus addressed only whether the person skilled in the art would have been motivated to “include”—that is, integrate—Iwaguchi’s detector into Kauffman’s system. The Board found no such motivation.

The Board’s reasoning largely mirrored Frymaster’s arguments. Kauffman’s system did not include a cooling mechanism that would have allowed Iwaguchi’s temperature-sensitive detector to work. Integrating Iwaguchi’s detector into Kauffman’s system would therefore necessitate the addition of the cooling mechanism. The Board agreed that the disadvantages of such additional construction outweighed the “uncertain benefits” of TPM measurements over the other indicia of oil quality already being monitored in Kauffman.

On appeal, HPC raised two issues: first, the Board construed the scope of HPC’s original petition overly narrowly; and second, the Board erred in its conclusion of nonobviousness.[1]

The Federal Circuit sided with the Board on both issues.

On the first issue, the Federal Circuit did a straightforward comparison of HPC’s petition and reply. In the petition, HPC proposed a physical substitution of Iwaguchi’s detector for Kauffman’s electrode. In the reply, HPC proposed using conductivity measured by Kauffman’s electrode as a basis for calculating TPMs. The apparent differences between the two theories of obviousness, together with the “telling” confirmation of HPC’s counsel during oral hearing that the original petition espoused a physical modification, made it easy for the Federal Circuit to agree with the Board’s decision to disregard HPC’s alternative theory raised in its reply.

The Federal Circuit reiterated the importance of a complete petition:

It is of the utmost importance that petitioners in the IPR proceedings adhere to the requirement that the initial petition identify ‘with particularity’ the ‘evidence that supports the grounds for the challenge to each claim.

On the second issue of obviousness, HPC argued that the Board placed undue weight on the disadvantages of incorporating Iwaguchi’s TPM detector into Kauffman’s system.

Here, the Federal Circuit reiterated “the longstanding principle that the prior art must be considered for all its teachings, not selectively.” While “[t]he fact that the motivating benefit comes at the expense of another benefit…should not nullify its use as a basis to modify the disclosure of one reference with the teachings of another”, “the benefits, both lost and gained, should be weighed against one another.”

The Federal Circuit adopted the Board’s findings on the undesirability of HPC’s proposed modification of Kauffman, agreeing that the “tradeoffs [would] yield an unappetizing combination, especially because Kauffman already teaches a sensor that measures other indicia of oil quality.”

At first glance, the nonobviousness analysis in this decision seems to involve weighing the disadvantages and advantages of the proposed modification. However, looking at the history of this case, I think the problem with HPC’s arguments was more fundamentally that they never identified a satisfactory motivation to make the proposed modification. HPC’s original petition argued that the motivation for integrating Iwaguchi’s detector into Kauffman’s system was to “accurately” determine oil quality. This “accuracy” argument failed because it was questionable whether Iwaguchi’s detector would even work at the operating temperature of a deep fryer. Further, HPC did not argue that the proposed modification was a simple substitution of one known sensor for another with the predictable result of measuring TPMs. And when Kauffman argued that the substitution was far from simple, HPC failed to counter with adequate reasons why the person skilled in the art would have pursued the complex modification.

Takeaway

- The petition for a post grant review defines the scope of the proceeding. Avoid being overly generic in a petition for post grant review. It may not be possible to fill in the details later.

- Context matters. If an Examiner is selectively citing to isolated disclosures in a prior art out of context, consider whether the context of the prior art would lead away from the claimed invention.

- The MPEP is clear that the disadvantages of a proposed combination of the prior art do not necessarily negate the motivation to combine (see, e.g., MPEP 2143(V)). The disadvantages should preferably nullify the Examiner’s reasons for the modification.

[1] On the issue of obviousness, HPC also objected to the Board’s analysis of Frymaster’s proffered evidence of industry praise as secondary considerations. This objection is not addressed here.