A Change in Language from IPR Petition to Written Decision May Not Result in A Change in Theory of Motivation to Combine

| September 25, 2019

Arthrex, Inc. v. Smith & Nephew, Corp.

August 21, 2019

Dyk, Chen, Opinion written by Stoll

Summary

The CAFC affirmed the Board’s decision that claims 10 and 11 of Patent ‘541 were obvious over Gordon in view of West and that the IPR proceeding was constitutional. The CAFC held that minor variations in wording, from the IPR Petition to the written Final Decision, do not violate the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). Further, the CAFC rejected Arthrex’s argument to reconsider evidence that was contrary to the Board’s decision since there was sufficient evidence to support the Board’s findings of obviousness by the preponderance of evidence standard.

Details

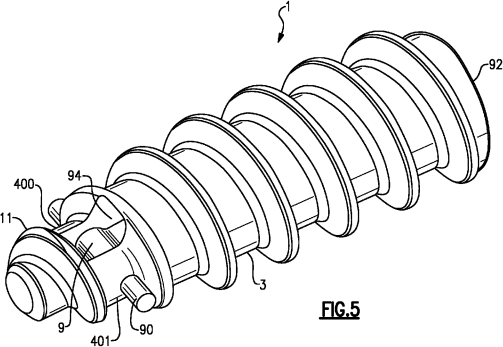

Arthrex’s Patent No. 8,821,541 (hereinafter “Patent ’541”) is directed towards a surgical suture anchor that reattaches soft tissue to bone. A feature of the suture anchor of Patent ‘541 is that the “fully threaded suture anchor’ includes ‘an eyelet shield that is molded into the distal part of the biodegradable suture anchor’”, wherein the eyelet shield is an integrated rigid support that strengthen the suture to the soft tissue. Id. at 2 and 3. The specification discloses that “because the support is molded into the anchor structure (as opposed to being a separate component), it ‘provides greater security to prevent pull-out of the suture.’ Id at col 5 ll. 52-56.” Id. at 3. Figure 5 of Patent ‘541 illustrates an embodiment of the suture anchor (component 1), wherein component 9 is the eyelet shield (integral rigid support) and component 3 is the body wherein helical threading is formed.

Claims 10 and 11 of Patent ‘541 are herein enclosed (emphasis added to the claim terms at issue in the dispute)

10. A suture anchor assembly comprising:

an anchor body including a longitudinal axis, a proximal end, a distal end, and a central passage extending along the longitudinal axis from an opening at the proximal end of the anchor body through a portion of a length of the anchor body, wherein the opening is a first suture opening, the anchor body including a second suture opening disposed distal of the first suture opening, and a third suture opening disposed distal of the second suture opening, wherein a helical thread defines a perimeter at least around the proximal end of the anchor body;

a rigid support extending across the central passage, the rigid support having a first portion and a second portion spaced from the first portion, the first portion branching from a first wall portion of the anchor body and the second portion branching from a second wall portion of the anchor body, wherein the third suture opening is disposed distal of the rigid support;

at least one suture strand having a suture length threaded into the central passage, supported by the rigid support, and threaded past the proximal end of the anchor body, wherein at least a portion of the at least one suture strand is disposed in the central passage between the rigid support and the opening at the proximal end, and the at least one suture strand is disposed in the first suture opening, the second suture opening, and the third suture opening; and

a driver including a shaft having a shaft length, wherein the shaft engages the anchor body, and the suture length of the at least one suture strand is greater than the shaft length of the shaft.

11. A suture anchor assembly comprising:

an anchor body including a distal end, a proximal end having an opening, a central longitudinal axis, a first wall portion, a second wall portion spaced opposite to the first wall portion, and a suture passage beginning at the proximal end of the anchor body, wherein the suture passage extends about the central longitudinal axis, and the suture passage extends from the opening located at the proximal end of the anchor body and at least partially along a length of the anchor body, wherein the opening is a first suture opening that is encircled by a perimeter of the anchor body, a second suture opening extends through a portion of the anchor body, and a third suture opening extends through the anchor body, wherein the third suture opening is disposed distal of the second suture opening;

a rigid support integral with the anchor body to define a single-piece component, wherein the rigid support extends across the suture passage and has a first portion and a second portion spaced from the first portion, the first portion branching from the first wall portion of the anchor body and the second portion branching from the second wall portion of the anchor body, and the rigid support is spaced axially away from the opening at the proximal end along the central longitudinal axis; and

at least one suture strand threaded into the suture passage, supported by the rigid support, and having ends that extend past the proximal end of the anchor body, and the at least one suture strand is disposed in the first suture opening, the second suture opening, and the third suture opening.

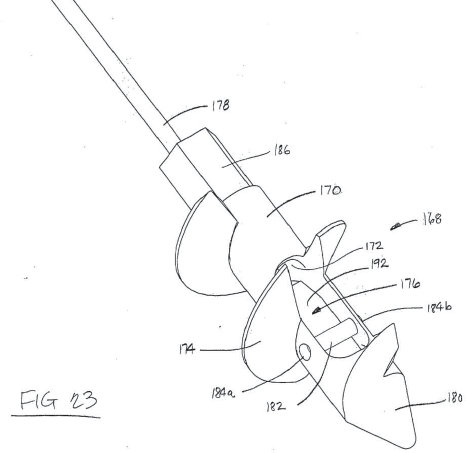

Smith & Nephew (hereinafter “Smith”) initiated an inter partes review of claims 10 and 11 of Patent ‘541. Smith alleged that claims 10 and 11 of Patent ‘541 were invalid as obvious over Gordon (U.S. Patent Application Publication No. 2006/0271060) in view of West (U.S. Patent No. 7,322,978) and alleged that claim 11 was anticipated by Curtis (U.S. Patent No. 5,464,427) (The discussion regarding Curtis (U.S. Patent No. 5,464,427) is not herein included). Smith argued that Gordon disclosed all the features claimed except for the rigid support. Gordon disclosed “a bone anchor in which a suture loops about a pulley 182 positioned within the anchor body. Figure 23 illustrates the pully 182 held in place in holes 184a, b.” Id. at 5 and 6.

Figure 23 of Gordon

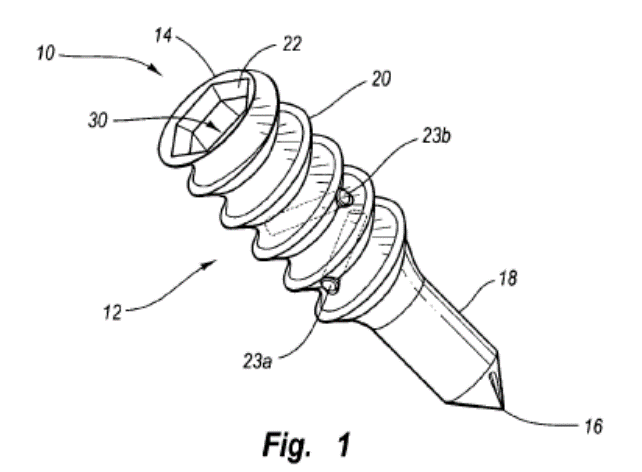

Smith acknowledged that the pulley of Gordon was not “integral with the anchor body to define a single-piece component”, a feature recited in claim 11 of Patent ‘541. Smith cited West to allege obviousness of this feature. West also disclosed a bone anchor wherein one or more pins are fixed within the bore of the anchor body. In West, “to manufacture the bone anchor, ‘anchor body 12 and posts 23 can be cast and formed in a die. Alternatively anchor body 12 can be cast or formed and post 23a and 23b inserted later.’” Id. at 7.

Figure 1 of West

Smith argued that it would have been obvious to a skilled artisan to form the bone anchor of Gordon by the casting process of West to thereby create a rigid support integral with the anchor body to define a single piece component, as recited in claim 11 of Patent ‘541. Smith’s expert testified that the casting process of West would “minimize the materials used in the anchor, thus facilitating regulatory approval, and would reduce the likelihood of the pulley separating from the anchor body.” Id. at 7. Smith asserted that the casting process of West was well-known in the art and that such a manufacturing process “would have been a simple design choice.” Id. at 7. Arthrex argued that a skilled artisan would not have been motivated to modify Gordon in view of West. The Board agreed with Smith that the claims were unpatentable. Arthrex filed an appeal.

Arthrex appealed the Board’s decision that Smith proved unpatentability of claims 10 and 11 in view of Gordon and West, on both a procedurally and a substantively basis, and the constitutionality of the IPR proceeding. The CAFC found that Arthrex’s procedural rights were not violated; that the Decision by the Board was supported by substantial evidence and the application of IPR to Patent ‘541 was constitutional.

IPR proceedings are formal administrative adjudications subject to the procedural requirements of the APA. See, e.g., Dell Inc. v. Acceleron, LLC, 818 F.3d 1293, 1298 (Fed. Cir. 2016); Belden, 805 F.3d at 1080. One of these requirements is that “‘an agency may not change theories in midstream without giving respondents reasonable notice of the change’ and ‘the opportunity to present argument under the new theory.’” Belden, 805 F.3d at 1080 (quoting Rodale Press, Inc. v. FTC, 407 F.2d 1252, 1256–57 (D.C. Cir. 1968)); see also 5 U.S.C. § 554(b)(3). Nor may the Board craft new grounds of unpatentability not advanced by the petitioner. See In re NuVasive, Inc., 841 F.3d 966, 971–72 (Fed. Cir. 2016); In re Magnum Oil Tools Int’l, Ltd., 829 F.3d 1364, 1381 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

Id. at 9.

Arthrex argued that the Board’s decision relied on a new theory of motivation to combine. Arthrex argued that the new theory violated their procedural rights by depriving them an opportunity to respond to said new theory. Arthrex argued that the Board’s reasoning differed from the Smith Petition by describing the casting method of West as “preferred.” The CAFC held that while the language used by the Board did differ from the Petition, said deviation did not introduce a new issue or theory as to the reason for combining Gordon and West. West disclosed “an ‘anchor body 12 and posts 23 can be cast and formed in a die. Alternatively anchor body 12 can be cast or formed and posts 23a and 23b inserted later’.” Id. at 10. The Smith Petition asserted that “a person of ordinary skill would have had ‘several reasons’ to combine West and Gordon, including that the casting process disclosed by West was a ‘well-known technique [whose use] would have been a simple design choice’.” (emphasis added) Id. at 10. In the written decision by the Board, the Board characterized West as disclosing two manufacturing methods, wherein the casting method was the “primary” and “preferred” method, and thus, a skilled artisan would have “applied West’s casting method to Gordon because choosing the ‘preferred option’ presented by West ‘would have been an obvious choice of the designer’.” Id. at 11. The CAFC noted that while the Board’s language of “preferred” differed from the language of the Petition, i.e. “well-known”, “accepted” and “simple”, the Board nonetheless relied upon the same disclosure of West as the Petition, the same proposed combination of the references and ruled on the same theory of obviousness, as presented in the Petition. “[t]he mere fact that the Board did not use the exact language of the petition in the final written decision does not mean it changed theories in a manner inconsistent with the APA and our case law…. the Board had cited the same disclosure as the petition and the parties had disputed the meaning of that disclosure throughout the trial. Id. As a result, the petition provided the patent owner with notice and an opportunity to address the portions of the reference relied on by the Board, and we found no APA violation.” Id. at 11.

Next, Arthrex argued that even if the Board’s decision was procedurally proper, an error was made by finding Smith had established a motivation to combine the cited art by a preponderance of the evidence. The CAFC held that there was sufficient substantial evidence to support the Board’s finding that a skilled artisan would be motivated to use the casting method of West to form the anchor of Gordon. First, the Board noted West’s disclosure of two methods of making a rigid support. Second, the wording by West suggested that casting was the preferred method. Third, Smith’s experts testified that the casting method would likely produce a stronger anchor, which in turn would be more likely to be granted regulatory approval. Also, casting would decrease manufacturing cost, produce an anchor that is less likely to interfere with x-rays and would reduce stress concentrations on the anchor. The CAFC agreed with Arthrex that there was some evidence that contradicts the Board’s decision, such as Arthrex’s expert’s testimony. However, “the presence of evidence supporting the opposite outcome does not preclude substantial evidence from supporting the Board’s fact finding. See, e.g., Falkner v. Inglis, 448 F.3d 1357, 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2006)”. Id. at 14. The CAFC refused to “reweight the evidence.” Id. at 14.

Lastly, the CAFC addressed Arthrex’s argument that an IPR is unconstitutional when applied retroactively to a pre-AIA patent. Since this argument was first presented on appeal, the CAFC could have chosen not to address it. However, exercising its discretion, the CAFC held that an IPR proceeding against Patent ‘541 was constitutional. Patent ‘541 was filed prior to the passage of the AIA, but was issued almost three years after the passage of the AIA and almost two years after the first IPR proceedings, on September 2, 2014. “As the Supreme Court has explained, ‘the legal regime governing a particular patent ‘depend[s] on the law as it stood at the emanation of the patent, together with such changes as have since been made.’” Eldred v. Ashcroft, 537 U.S. 186, 203 (2003) (quoting McClurg v. Kingsland, 42 U.S. 202, 206 (1843)). Accordingly, application of IPR to Arthrex’s patent cannot be characterized as retroactive.” Id. at 18. The CAFC further explained that even if Patent ‘541 issued prior to the AIA, an IPR would have been constitutional. “[t]he difference between IPRs and the district court and Patent Office proceedings that existed prior to the AIA are not so significant as to ‘create a constitutional issue’ when IPR is applied to pre-AIA patents.” Id. at 18.

Takeaway

- Slight changes in language does not create a new theory of motivation to combine.

- However, a new theory of motivation to combine

may exist when:

- the Board

creates a new theory of obviousness by mixing arguments from two different

grounds of obviousness presented in a Petition.

- In re Magnum Oil Tools Int’l, Ltd., 829 F.3d 1364, 1372–73, 1377 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

- the claim construction by the Board varies

significantly from the uncontested construction announced in an institution

decision.

- SAS Institute v. ComplementSoft, LLC, 825 F.3d 1341, 1351 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

- the Board

relies upon a portion of the prior art, as an essential part of its obviousness

finding, that is different from the portions of the prior art cited in the

Petition.

- In re NuVasive, Inc., 841 F.3d 966, 971 (Fed. Cir. 2016).

- the Board

creates a new theory of obviousness by mixing arguments from two different

grounds of obviousness presented in a Petition.