CLAIM CONSTRUCTION – WHEN THE MEANING IS CLEAR FROM INTRINSIC EVIDENCE, THERE IS NO REASON TO RESORT TO EXTRINSIC EVIDENCE

| September 8, 2021

Seabed Geosolutions (US) Inc., v. Magseis FF LLC

Decided August 11, 2021

Before Moore, Linn and Chen

Summary

This precedential opinion reminds us of when it is proper to rely on extrinsic evidence when construing the meaning of claim terms. Claim construction begins with the intrinsic evidence, which includes the claims, written description, and prosecution history. If the meaning of a claim term is clear from the intrinsic evidence, there is no reason to resort to extrinsic evidence.

Background

Fairfield Industries Inc. (the predecessor to Magseis) had sued Seabed Geosolutions for infringement of U.S. Reissue Patent No. RE45,268 directed to seismometers. Seabed Geosolutions petitioned for inter partes review which was instituted by the Board. Interestingly, although not in the opinion, the Board’s institution decision had commented on the meaning of the claim term at issue, “internally fixed.” The institution decision specifically noted that there was nothing in the specification to suggest an intent for “internally fixed” to exclude gimbaled, specifically quoting Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303, 1315 (Fed. Cir. 2005) that the specification “is the single best guide to the meaning of a disputed term” and is usually “dispositive.” The institution decision went on to conclude that the specification does not appear to limit “internally fixed” and instead appears to contemplate a broad meaning.

During the IPR proceeding, however, extrinsic evidence had been presented, causing the Board to find that the specification was not dispositive one way or the other as to the meaning of “internally fixed.” Nine pages of the Board’s decision (also not specifically discussed by the CAFC) was dedicated to a discussion of “internally fixed.” The Board, looking at the extrinsic evidence, thus concluded that in the context of the field of art, one of ordinary skill would understand that the term “fixed” indicates that the geophone is not gimbaled.

Discussion

Every independent claim of the ‘268 patent recites “a geophone internally fixed within” either a housing or an internal compartment. Geophones are used to detect seismic reflections from subsurface structures. The Board concluded that the prior art cited in the IPR failed to disclose the geophone limitation. Seabed appealed by arguing that the Board erred in it claim construction of the geophone limitation.

The CAFC reviews the Board’s claim construction and any supporting determinations based on intrinsic evidence de novo, while subsidiary fact findings involving extrinsic evidence are reviewed for substantial evidence. The CAFC emphasized prior precedent indicating:

For inter partes review petitions filed before November 13, 2018, the Board uses the broadest reasonable interpretation (BRI) standard to construe claim terms. See 37 C.F.R. § 42.100(b) (2017). Under that standard, “claims are given their broadest reasonable interpretation consistent with the specification, not necessarily the correct construction under the framework laid out in Phillips.” PPC Broadband, Inc. v. Corning Optical Commc’ns RF, LLC, 815 F.3d 734, 742 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (citing Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (en banc)). But we still “give[] primacy” to intrinsic evidence, and we resort to extrinsic evidence to construe claims only if it is consistent with the intrinsic evidence. Tempo Lighting, Inc. v. Tivoli, LLC, 742 F.3d 973, 977 (Fed. Cir. 2014); see also Phillips, 415 F.3d at 1318 (“[A] court should discount any expert testimony ‘that is clearly at odds with the claim construction mandated by the claims themselves, the written description, and the prosecution history.’” (quoting Key Pharms. v. Hercon Labs. Corp., 161 F.3d 709, 716 (Fed. Cir. 1998))).

Based on the given standard, the CAFC reviewed the Board’s construction that “geophone internally fixed within [the] housing” requires a non-gimbaled geophone. The CAFC had noted that the Board’s construction was based entirely on extrinsic evidence. This was an error because claim construction begins with examining the intrinsic evidence (claims, written description and prosecution history). Of note, if the meaning of a claim term is clear from the intrinsic evidence, there is no reason to resort to extrinsic evidence (citing Profectus Tech. LLC v. Huawei Techs. Co., 823 F.3d 1375, 1380 (Fed. Cir. 2016)(“Extrinsic evidence may not be used ‘to contradict claimmeaning that is unambiguous in light of the intrinsic evidence.’”(quoting Phillips, 415 F.3d at 1324)).

Based upon the intrinsic evidence, “fixed” carries its ordinary meaning of attached or fastened. The adverb “internally” with “fixed” specifies the geophone’s relationship with the housing, not the type of geophone, which is consistent with the specification. The specification describes mounting the geophone inside the housing as a key feature and says nothing about the geophone being gimbaled or non-gimbaled. The specification touted the “self-contained” approach 18 times and never mentions gimbaled or non-gimbaled, nor providing a reason to exclude gimbals.

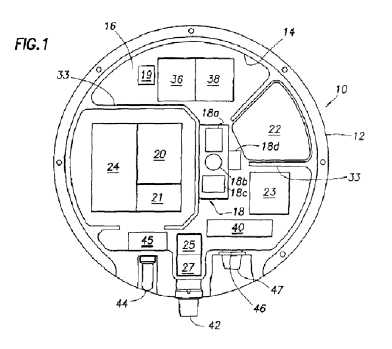

Magseis had attempted to argue that Fig. 1 limits the claims to a non-gimbaled geophone, but this was not persuasive. Fig. 1 merely disclosed geophone 18 as a black box.

The prosecution history also suggests the construction of the word fixed as meaning mounted or fastened. Each time the word came up, the applicant and examiner understood it in its ordinary sense to mean mounted or fastened. Since the intrinsic evidence consistently informed a skilled artisan that fixed means mounted or fastened, “resort to extrinsic evidence is unnecessary.” As such, the Board erred in reaching a narrower interpretation.

Takeaways

If the meaning of a claim term is clear from the intrinsic evidence, there is no reason to resort to extrinsic evidence.

Extrinsic evidence may not be used to contradict claim meaning which is unambiguous in light of the intrinsic evidence.