“Kitchen” Sinks QuikTrip’s Trademark Opposition: The Federal Circuit Explains that Although Trademarks are Evaluated in their Entireties, when Determining Similarities between Trademarks, More Weight Is Applied to Distinctive Aspects of the Trademarks

| January 20, 2021

Quiktrip West, Inc. v. Weigel Stores, Inc

January 7, 2021

Lourie, O’Malley, and Reyna, (Opinion by Lourie)

Summary

QuikTrip filed a trademark opposition in the U.S. Patent & Trademarks Office (U.S.P.T.O.) against Weigel in relation to Weigel’s application for the trademark W Kitchens based on QuikTrip’s assertion that Weigel’s trademark is likely to cause confusion in relation to Quiktrip’s registered trademark QT Kitchen. The Board at the U.S.P.T.O. found that the dissimilarity of the marks weighed against the likelihood of confusion and dismissed QuikTrip’s opposition. On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed the Board’s decision. The Federal Circuit explained that the Board correctly evaluated the trademarks in their entireties, while properly giving lower weight to less distinctive aspects of the trademark, such as the term “kitchen.” The Federal Circuit also noted that although some evidence suggested that Weigel may have copied QuikTrip’s trademark, the fact that Weigel modified its trademark multiple times in response to QuikTrip’s allegations of infringement negated any inference of an intent to deceive or cause confusion.

Background

- The Factual Setting

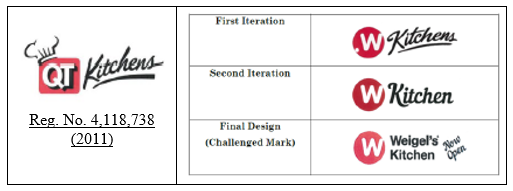

QuikTrip operates a combination gasoline and convenience store, and has sold food and beverages under its registered mark QT Kitchens (shown below left) since 2011.

In 2014, Weigel started using the stylized mark W Kitchens shown at the top-right below (First Iteration). QuikTrip sent Weigel a cease-and-desist letter. In response, Weigel adapted its mark to change Kitchens to Kitchen and to adapt the stylizing as shown at the middle-right below (Second Iteration). In response, QuikTrip demanded further modification by Weigel, and Weigel again adapted its mark to further change the font, to add its’ name Weigel’s and to include “new open” as shown at the bottom-right below (Final Challenged Mark).

The U.S.P.T.O. Proceedings

Weigel applied to register its’ Final Challenged Mark with the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (application no. 87/324,199), and QuikTrip filed an opposition to Weigel’s mark under 15 U.S.C. 1052(d) asserting that it would create a likelihood of confusion with its QT Kitchens mark.

The Board evaluated the likelihood of confusion and found that the dissimilarity of the marks weighed against the likelihood of confusion and dismissed QuikTrip’s opposition to Weigel’s registration of its mark.

QuikTrip appealed the Board’s decision to the Federal Circuit.

The Federal Circuit’s Decision

The Federal Circuit reviews the Board’s legal determination de novo, but reviews the underlying findings of fact based on substantial evidence.

Here, the legal analysis involves the determination of whether the mark being sought is “likely, when used on or in connection with the goods of the applicant, to cause confusion” with another registered mark. See 15 U.S.C. 1052(d) of the Lanham Act. The likelihood of confusion evaluation is a legal determination based on underlying findings of fact relating to the longstanding factors set forth in E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., 476 F. 2d 1357 (C.C.P.A. 1973). For reference, these factors include:

- The similarity of the marks (e.g., as viewed in their entireties as to their appearance, sound, connotation, and commercial impression);

2. The similarity and nature of the goods and services;

3. The similarity of the established trade channels;

4. The conditions under which, and buyers to whom, sales are made (e.g., impulse

verses sophisticated purchasing);

5. The fame of the prior mark;

6. The number and nature of similar marks in use on similar goods (e.g., by 3rd

parties);

7. The nature and extent of any actual confusion;

8. The length of time during, and the conditions under which, there has been

concurrent use without evidence of actual confusion;

9. The variety of goods on which a mark is or is not used;

10. The market interface between the applicant and the owner of a prior mark;

11. The extent to which applicant has a right to exclude others from use of its mark;

12. The extent of possible confusion;

13. Any other established fact probative of the effect of use.

On Appeal, QuikTrip challenges the Board’s analysis regarding the Dupont factor number one (1) based on “similarity of the marks” and the Dupont factor thirteen (13) based on “other established fact probative of the effect of use” which other fact is asserted by QuikTrip as being the “bad faith” of Weigel.

- Factor 1 (Similarity of the Marks)

With respect to the first factor pertaining to the similarity of the marks, QuikTrip asserted that the Board incorrectly “dissected the marks when analyzing their similarity” rather than rendering its determination based on the similarity of “the marks in their entireties.”

First, QuikTrip argued that the Board improperly “ignored the substantial similarity created by … the shared word Kitchen(s)” and gave “undue weigh to other dissimilar portions of the marks.” In response, the Federal Circuit explained that “[i]t is not improper for the Board to determine that ‘for rational reasons’ it should give ‘more or less weight’ to a particular feature of the mark” as long as “its ultimate conclusion … rests on a consideration of the marks in their entireties.”

Here, the Federal Circuit indicated that the portion “Kitchen(s)” should “accord less weight” because “kitchen” is a “highly suggestive, if not descriptive, word” and also because there were numerous “third-party uses, and third-party registrations of marks incorporating the word “kitchen” for sale of food and food-related services.”

Moreover, the Federal Circuit explained that “the Board was entitled to afford more weight to the dominant, distinct portions of the marks” which included “Weigel’s encircled W next to the surname Weigel’s and QuikTrip’s QT in a square below a chef’s hat” emphasizing “given their prominent placement, unique design and color.”

The Federal Circuit also noted that the Board compared the marks in their entireties and further observe that: 1) the marks contained different letters and geometric shapes; 2) QuikTrip’s mark included a tilted chef’s hat; 3) phonetically, the marks do “not sound similar,” and the component Weigel’s adds an entirely different sound; and 4) the commercial impressions and connotations are different.

Accordingly, the Federal Circuit expressed that the Board’s finding of a lack of similarity was supported by substantial evidence.

- Factor 13 (Bad Faith as Another Probative Factor)

With respect to the thirteenth factor pertaining to asserted “bad faith” as being another probative factor, QuikTrip asserted that the evidence showed that Weigel acted in bad faith and that such bad faith further supported a finding of a likelihood of confusion.

However, the Federal Circuit explained that “an inference of ‘bad faith’ requires something more than mere knowledge of a prior similar mark.” Moreover, the Federal Circuit further explained that “[t[he only relevant intent is [an] intent to confuse.” The Federal Circuit noted that “[t]here is a considerable difference between an intent to copy and an intent to deceive.”

Accordingly, although the evidence showed that Weigel had taken photographs of QuikTrip’s stores and examined QuikTrip’s marketing materials, the Federal Circuit expressed that there was not an intent to deceive. In particular, the Federal Circuit emphasized that Weigel’s “willingness to alter its mark several times in order to prevent customer confusion [in response to QuikTrip’s cease-and-desist demands] negates any inference of bad faith.”

Accordingly, the Federal Circuit affirmed the decision of the Board.

Takeaways

- In evaluating similarities between trademarks for the determination of potential likelihood of confusion, although the evaluation is based on the marks in their entireties, different portions of the marks may be afforded different weight depending on circumstances. Accordingly, it is important to identify portions of the mark that are more distinctive in contrast to portions of the mark that may be descriptive or suggestive or commonly used in other marks.

- Although “bad faith” can help support a conclusion of a likelihood of confusion, it is important to keep in mind that “bad faith” does not merely require an “intent to copy,” but requires an “intent to deceive.”

- In the event that a trademark owner demands an alleged infringer cease-and-desist use of a mark, if the accused infringer substantially modifies its trademark in an effort to prevent customer confusion, according to the Federal Circuit, such action would “negate any inference of bad faith.” Accordingly, in order to help avoid any inference of bad faith, in response to a cease-and-desist demand, an accused infringer can help to avoid such an inference by modifying its trademark.