When the Broadest Reasonable Interpretation (BRI) Becomes Unreasonable

| March 26, 2020

Kaken Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Bausch Health Companies Inc. v. Andrei Iancu, Under Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property and Director of the United States Patent and Trademark Office

March 13, 2020

Before Newman, O’Malley, and Taranto (Opinion by Taranto)

U.S. patent practitioners constantly need to address use of the broadest reasonable interpretation (BRI) by Examiners during patent prosecution. During prosecution, arguments and amendments are typically presented to overcome prior art and become a part of the prosecution history along with the disclosure of the invention. This decision illustrates that definitions provided in the specification in conjunction with the prosecution history can potentially save a patent from a later challenge which invokes BRI. In this case, an erroneous claim construction of one claim limitation during an inter partes review caused the CAFC to reverse and remand back to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB).

U.S. patent No. 7,214,506 is directed a method for treating onychomycosis. Claim 1 recites:

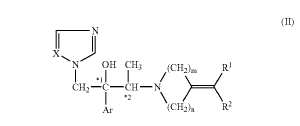

1. A method for treating a subject having onychomycosis wherein the method comprises topically administering to a nail of said subject having onychomycosis a therapeutically effective amount of an antifungal compound represented by the following formula:

wherein, Ar is a non-substituted phenyl group or a phenyl group substituted with 1 to 3 substituents selected from a halogen atom and trifluoromethyl group,

R1 and R2 are the same or different and are hydrogen atom, C1-6 alkyl group, a non-substituted aryl group, an aryl group substituted with 1 to 3 substituents selected from a halogen atom, trifluoromethyl group, nitro group and C1-16 alkyl group, C2-8 alkenyl group, C2-6 alkynyl group, or C7-12 aralkyl group,

m is 2 or 3,

n is 1 or 2,

X is nitrogen atom or CH, and

*1 and *2 mean an asymmetric carbon atom.

Acrux[1] had successfully obtained inter partes review of all claims of the ‘506 patent, with the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) ultimately determining that all claims are unpatentable for obviousness (based on a set of three references in combination with another set of two references for six total grounds). The first set of three references teach a method of topically treating onychomycosis with various azole compounds while the second set teaches KP-103 (an azole compound within the scope of claim 1) as an effective antifungal agent.

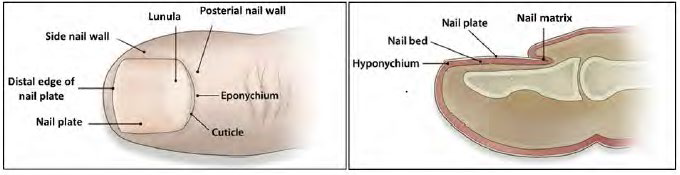

Kaken had argued that the phrase “treating a subject having onychomycosis” means “treating the infection at least where it primarily resides in the keratinized nail plate and underlying nail bed.” Kaken argued that the ‘506 patent’s key innovation is a topical treatment that can easily penetrate the tough keratin in the nail plate. This construction was rejected by the PTAB as too narrow because of the express definition of onychomycosis as including superficial mycosis, and the express definition in the specification of “nail includes the tissue or skin around the nail plate, nail bed, and nail matrix.” The PTAB concluded that “treating onychomycosis” includes treating “superficial mycosis that involves the skin or visible mucosa.”

The nail plate is defined as the “horny appendage of the skin that is composed mainly of keratin” whereas the “eponychium and hyponychium” are “the skin structures surrounding the nail.”

The CAFC reversed the PTAB’s claim construction as unreasonable in light of the specification and prosecution history as the broadest reasonable interpretation of treating a subject having onychomycosis “is penetrating the nail plate to treat a fungal infection inside the nail plate or in the nail bed under it.”

The CAFC came to this conclusion based on the specification’s characterization of onychomycosis in a way which links three other crucial passages. In particular, after defining the terms “skin” and “nail” and characterizing “superficial mycosis”, the specification stated that onychomycosis is “a kind of the above-mentioned superficial mycosis, in the other word a disease which is caused by invading and proliferating in the nail of human or an animal.” Thus, the specification conveys that onychomycosis is a disease with two basic features (1) of a disease of the nail and (2) it is a kind of superficial mycosis. As such, the BRI of onychomycosis would not include invasion of any part of what is defined as the nail other than the nail plate or nail bed, such as skin in its ordinary sense. The PTAB’s inclusion of the eponychium and hyponychium is unreasonable as the specification defined that onychomycosis is a disease involving invasion of the nail.

Other parts of the specification explain that an effective topical treatment would need to penetrate the nail plate, and the ‘506 patent explained that known topical treatments were largely ineffective. The patent further contains as objects as good permeability, good retention capacity and conservation of high activity to indicate that treating an infection of skin surrounding the nail plate alone would not require all these properties.

The prosecution history also included statements overcoming prior art as providing “decisive support” for Kaken’s claim construction. Kaken’s statements, followed by the examiner’s statements, make clear the limits on a reasonable understanding of what Kaken was claiming. The exchange between the examiner and Kaken:

“would leave a skilled artisan with no reasonable uncertainty about the scope of the claim language in the respect at issue here. Kaken is bound by its arguments made to convince the examiner that claims 1 and 2 are patentable. See Standard Oil, 774 F.2d at 452. Thus, Kaken’s unambiguous statement that onychomycosis affects the nail plate, and the examiner’s concomitant action based on this statement, make clear that “treating onychomycosis” requires penetrating the nail plate to treat an infection inside the nail plate or in the nail bed under it.”

Since the PTAB relied upon an erroneous claim construction throughout its consideration of facts in its obviousness analysis, the CAFC vacated the PTAB’s decision and remanded.

Takeaways:

Intrinsic evidence in the specification can overcome an ordinary meaning in the art (extrinsic evidence).

Although an applicant desires a broad interpretation of patent claims, too broad of an interpretation can open the patent to attacks. As such, the prosecution history plays an important role.

Some past decisions have taught patent

practitioners to avoid stating objects of the invention or discussion of prior

art. However, stating objects and providing a discussion of prior art can be

important for securing a proper claim construction, particularly in “crowded”

art areas.

[1] Acrux withdrew from the appeal, and the Director intervened to defend the PTAB’s decision.