A Claim term referring to an antecedent using “said” or “the” cannot be independent from the antecedent

| February 24, 2023

Infernal Technology, LLC v. Activision Blizzard Inc.

Decided: January 24, 2023

Moore, Chen, Stoll. Opinion by Chen.

Summary:

Infernal sued Activision for infringement of its patents to lighting and shadowing methods for use with computer graphics based on nineteen Activision video games. Based on the construction of the claim term “said observer data,” Activision filed a motion for summary judgment of non-infringement. The CAFC agreed with the District Court’s analysis of the noted claim term and affirmed the motion for summary judgment of non-infringement.

Details:

Infernal owns the related U.S. Patent Nos. 6,362,822 and 7,061,488 to “Lighting and Shadowing Methods and Arrangements for Use in Computer Graphic Simulations” providing methods of improving how light and shadow are displayed in computer graphics. Claim 1 of the ‘822 patent is provided:

1. A shadow rendering method for use in a computer system, the method comprising the steps of:

[1(a)] providing observer data of a simulated multi-dimensional scene;

[1(b)] providing lighting data associated with a plurality of simulated light sources arranged to illuminate said scene, said lighting data including light image data;

[1(c)] for each of said plurality of light sources, comparing at least a portion of said observer data with at least a portion of said lighting data to determine if a modeled point within said scene is illuminated by said light source and storing at least a portion of said light image data associated with said point and said light source in a light accumulation buffer; and then

[1(d)] combining at least a portion of said light accumulation buffer with said observer data; and

[1(e)] displaying resulting image data to a computer screen.

(Emphasis added).

The parties agreed to the construction of the term “observer data” as meaning “data representing at least the color of objects in a simulated multi-dimensional scene as viewed from an observer’s perspective.” The district court adopted this construction. Based on this construction and the plain and ordinary meaning of the limitation “said observer data” in step 1(d), Activision filed a motion for summary judgment of non-infringement, and the district court granted the summary judgment.

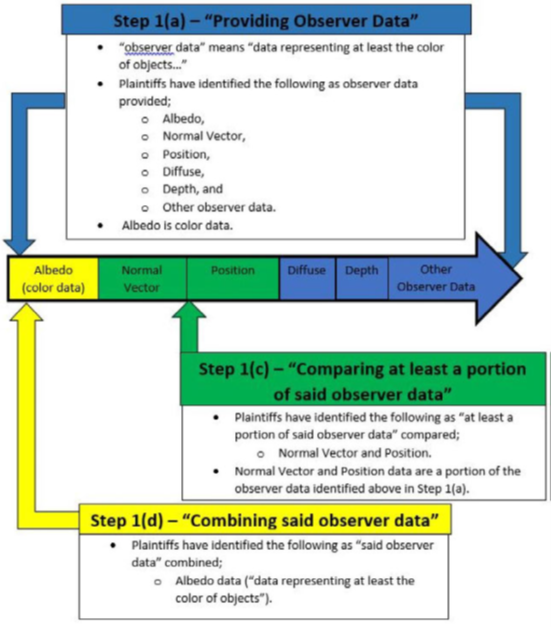

On appeal, Infernal argued that the district court misapplied its own construction of “observer data.” Infernal argued that “observer data” can refer to different data sets in steps 1(a), 1(c) and 1(d), each different data set independently satisfying the “observer data” construction. Step 1(a) recites “providing observer data,” step 1(c) recites “comparing at least a portion of said observer data,” and step 1(d) recites “combining … with said observer data.” The reason Infernal applies this construction is due to their infringement theory summarized below:

In its infringement theory, for step 1(a) Infernal refers to albedo (color data), normal vector, position, diffuse, depth, and other observer data; for step 1(c), Infernal refers to normal vector and position data; and for step 1(d), Infernal refers to only albedo data. Thus, Infernal’s infringement theory relies on applying different obverser data for steps 1(a), 1(c) and 1(d). Infernal argued that “said observer data” in step 1(d) can refer to a narrower set of data than “observer data” in step 1(a) because both independently meet the district court’s construction of “observer data.”

In analyzing Infernal’s argument, the CAFC stated the principal that “[in] grammatical terms, the instances of [‘said’] in the claim are anaphoric phrases, referring to the initial antecedent phrase” citing Baldwin Graphic Sys., Inc. v. Siebert, Inc., 512 F.3d 1338, 1342 (Fed. Cir. 2008). The CAFC further stated that based on this principle, the term “said observer data” recited in steps 1(c) and 1(d) must refer back to the “observer data” recited in step 1(a), and concluded that “the ‘observer data’ in step 1(a) must be the same “observer data” in steps 1(c) and 1(d).” The CAFC stated that this analysis applies even though the district court’s construction of “observer data” encompasses “at least color data.” In concluding that term “observer data” cannot refer to different data among steps 1(a), 1(c) and 1(d), the CAFC stated:

Although the initial “observer data” in step 1(a) includes data that is “at least color data,” the use of the word “said” indicates that each subsequent instance of “said observer data” must refer back to the same “observer data” initially referred to in step 1(a). An open-ended construction of “observer data” (“data representing at least the color of objects”) does not permit each instance of “observer data” in a claim to refer to an independent set of data.

Regarding the district court’s finding that Infernal failed to raise a genuine issue of material fact, Infernal argued that the district court erred in its finding that the accused video games cannot perform the claimed steps in the specified sequence. The district court held that Infernal failed to raise a genuine issue of material fact as to the accused games performing limitation 1(d): “combining … with said observer data.”

The CAFC agreed with the district court. Referring to Infernal’s infringement theory diagram, the CAFC stated that for step 1(a), Infernal identified “observer data” as albedo (color data), normal vector, position, diffuse, depth, and other observer data, but for step 1(d), Infernal identified “said observer data” as only albedo (color data). “Because it is undisputed that the mapping of the Accused Games’s ‘observer data’ in step 1(a) is different than the mapping of the “observer data” in step 1(d), … there is no genuine issue of material fact as to whether the Accused Games infringe [step 1(d)].” The CAFC also pointed out that Infernal’s mapping for step 1(d) improperly excludes data that is mapped to “a portion of said observer data” in step 1(c).

Comments

In a footnote, the CAFC stated that this analysis is consistent with other cases in which the use of the word “said” or “the” refers back to the initial limitation, “even when the initial limitation refers to one or more elements.” When drafting claims, if you intend for a later recitation of the same limitation to refer to an independent instance of the limitation, then you will need to modify the language rather than merely using “said” or “the.”

It appears that if step 1(d) in Infernal’s claim referred to “at least a portion of said observer data,” Infernal would have had a better argument that the observer data in step 1(d) can be a narrower data set than the “observer data” in step 1(a). The CAFC also pointed out that Infernal knew how to do this because that is what they did in step 1(c) and chose not to in step 1(d).

Obvious Claim Limitation Fails to Present Different Issues of Patentability Needed to Deny Collateral Estoppel

| February 16, 2023

Google LLC V. Hammond Development International, Inc.

Decided: December 8, 2022

Moore, Chen, and Stoll. Opinion by Moore.

Summary

On appeal from an inter partes review (IPR) decision finding some claims of a first patent not unpatentable over prior art, where counterpart claims of a related, second patent had been invalidated in another IPR decision, the CAFC found that the second IPR decision has collateral estoppel effect on certain challenged claims of the first patent where slight difference in claim language immaterial to the question of validity in the underlying decision does not present different issues of patentability.

Details

Google filed IPR petitions against Hammond’s patents including U.S. Patent Nos. 10,270,816 (“’816 patent”) and No. 9,264,483 (“’483 patent”). Hammond’s challenged patents relate to a communication system that allows a communication device to remotely execute one or more applications. The specification shared by these patents discloses that the inventive system enables a user to check a bank account balance or airline flight status by using a cell phone or other communication devices to interact with application servers over a network, which in turn access database storing applications so as to perform the desired functionalities. As seen in Figs. 1A-1D, for example, the system may be implemented using a single application server or multiple application servers.

In the ‘816 IPR, Google challenged all the claims of the patent, asserting different prior art combinations against different subsets of claims. Relevant to this case are obviousness challenges of claims 1, 14 and 18 which recite, among other things, one or both of two particular limitations referred to as first[1] and second[2] “request for processing service” limitations, as summarized below:

| Claims | “request for processing service” limitations recited | References/Basis |

| Independent claim 1 | Both first and second limitations | Gilmore, Dhara, and Dodrill |

| Independent claim 14 | First limitation | Gilmore and Creamer |

| Claim 18 dependent from claim 14 | Second limitation | Gilmore, Creamer and Dodrill |

As to claim 1, Google asserted that Gilmore and Dodrill in combination would meet the first and second limitations. As to claim 14, however, Google did not rely on Dodrill for the first limitation in particular. Instead, Google included Dodrill solely to obviate the second limitation as recited in claim 18 dependent from claim 14.

The above choice of references caused trouble to Google. The Board, finding Gilmore and Dodrill in combination as teaching both the first and second limitations in claim 1, determined that the combination of Gilmore and Creamer would not do so with the first limitation as recited in claim 14. Further, Google’s assertion of invalidity as to dependent claim 18 also failed with the contrary finding of claim 14; even though Google did rely on Dodrill for the second limitation as recited in claim 18, that reliance did not extend to the first limitation in parent claim 14. On June 4, 2021, a final written decision was issued in the ‘816 IPR, determining that claims 1–13 and 20–30 would have been obvious, but not claim 14 and its dependent claims 15–19.

On April 12, 2021, prior to the ‘816 IPR decision, the ‘483 IPR had concluded in a final written decision invalidating all the challenged claims for obviousness over prior art including Gilmore and Dodrill. Among those invalidated claims was claim 18 of the ‘483 patent, which recites both the first and second “request for processing service” limitations as in claim 18 of the ‘816 patent.

Google appealed the IPR rulings on claims 14-19 of the ‘816 patent to the CAFC. Google asserted, among other things, that collateral estoppel effect of the invalidity determination of claim 18 of the ‘483 patent renders claim 18 of the ‘816 patent also unpatentable. Finding collateral estoppel as applicable to this case, the CAFC reversed as to claims 14 and 18, and affirmed as to claims 15-17 and 19.

No forfeiture of collateral estoppel

As a preliminary matter, the CAFC found that Google’s omission of its collateral estoppel argument in the IPR petition does not cause forfeiture. Since the issuance and the finality of the ‘483 final written decision took place only after Google’s filing of the ‘816 IPR petition, the argument based on non-existent preclusive judgement could not have been included in that petition. As such, the CAFC held that Google is allowed to raise its collateral estoppel argument for the first time on appeal.

Collateral estoppel – Identicality requirement

Noting that the collateral estoppel can apply in IPR proceedings, the CAFC recited the four requirements for the preclusive effect to exist under In re Freeman:

(1) the issue is identical to one decided in the first action; (2) the issue was actually litigated in the first action; (3) resolution of the issue was essential to a final judgment in the first action; and (4) [the party against whom collateral estoppel is being asserted] had a full and fair opportunity to litigate the issue in the first action.

Only the first element was disputed in the present case. Citing its precedents, the CAFC emphasized that the identicality requirement concerns identicality of “the issues of patentability” (emphasis original), rather than the claim language per se. As such, applicability of collateral estoppel is not affected by mere existence of slightly different wording used to depict a substantially identical invention so long as the differences between the patent claims “do not materially alter the question of invalidity,” which is “a legal conclusion based on underlying facts.”

Claim 18 – Invalid for collateral estoppel

The CAFC held that collateral estoppel applies so as to render the claim 18 of the ‘816 patent unpatentable because it shares identical issues of patentability with the invalidated claim 18 of the ’483 patent. Specifically, the CAFC noted that “only difference between the claims is the language describing the number of application servers”: The claim 18 of the ‘816 patent recites “a plurality of application servers” including “first one” and “second one” configured to perform certain respective functions specifically associated therewith, whereas the claim 18 of the ‘483 patent requires “one or more application servers” or “the at least one application server” to perform the requisite functionality. The CAFC found that the difference is immaterial to the question of invalidity in the collateral estoppel analysis, relying on the Board’s factual findings that the above limitation of claim 18 of the ‘816 patent would have been obvious to a skilled artisan, as supported by Google’s expert evidence, which were not challenged by Hammond on appeal.

Claim 14 – Invalid for invalidation of dependent claim 18

Having found claim 18 unpatentable, the CAFC went on to hold that independent claim 14, from which claim 18 depends, is also unpatentable. In so doing, the CAFC noted that the parties had agreed on the invalidity consequence of the parent claim based on the invalidated dependent claim[3]. In a footnote, the Opinion states that since Hammond failed to assert that Google’s collateral estoppel arguments should be limited to the references asserted in the petition, the impact of Google’s original invalidity challenge against claim 14—which does not use the same combination of references as claim 18—was not explored.

Claims 15-17 and 19 – Not unpatentable due to lack of collateral estoppel arguments

The CAFC distinguished the remaining claims from claim 18 and claim 14. Unlike claim 18, Google made no collateral estoppel arguments against claims 15-17 and 19. Rather, Google’s arguments as to these claims relied on the Board’s obviousness findings as to parallel dependent claims. Moreover, unlike claim 14, Hammad did not admit that invalidity of claim 18 is consequential to unpatentability of claims 15-17 and 19. As such, Google failed to meet its burden to provide convincing arguments for reversal on appeal.

Takeaway

This case depicts an interplay between collateral estoppel analysis on appeal and obviousness findings in underlying litigation: The identicality of the issues of patentability exists where the adjudicated and the unadjudicated claims are substantially the same with their only difference being a limitation that has been found as obvious. Parties in parallel actions involving patent claims of the same family may want to be mindful of potential impact of obviousness determination as to a claim limitation unique to one patent but not in the other in the future inquiry of collateral estoppel.

[1] Recited as “the application server is configured to transmit … a request for processing service … to the at least one communication device” in claim 1 of the ‘816 patent.

[2] Recited as “wherein the request for processing service comprises an instruction to present a user of the at least one communication device the voice representation” in claim 1 of the ‘816 patent.

[3] “[T]he patentability of claim 14 rises and falls with claim 18.” During oral argument, this principle was noted referring to Callaway Golf Co. v. Acushnet Co. (Fed. Cir., August 14, 2009).