Primer in Patent Enforcement

| May 26, 2022

NICHIA CORPORATION, v. DOCUMENT SECURITY SYSTEMS, INC.

Decided: April 26, 2022

Before DYK, REYNA, and STOLL. Opinion by REYNA

Summary

Although not precedential, this decision serves as a primer on patent enforcement and the interplay of district court actions by a patent owner, and defenses raised by an alleged infringer with a petition for inter partes review. A review of the underlying Board decision reveals eight district court cases brought by Document Security Systems, Inc., against six different entities, where three inter partes reviews were requested. There were also petitions for inter partes reviews (IPRs) of different patents owned by Document Security Systems, Inc. not involved in this appeal.

In one of the IPRs, the Board found claims 1, 6-8, 15 and 17 of USP 7,524,087 (the ‘087 patent which is the patent involved in the decision) unpatentable (Seoul Semiconductor Co. v. Document Sec. Sys., Inc., IPR2018-00522 and Everlight Elecs. Co. v. Document Sec. Sys., Inc., IPR 2018-01226 – motion for joinder with IPR 2018-00522). In another IPR, the Board declined to institute inter partes review due to the petition being filed more than one year after service of the complaint alleging infringement (Cree, Inc., v. Document Sec. Sys., Inc., IPR2018-01221).

In the present decision, the Board found claims 1 and 6-8 of the ‘087 patent unpatentable and found that claims 2-5 and 9-19 of the ‘087 patent are not unpatentable. Nichia appeals the decision upholding claims 2-5 and 9-19 while Document Security Systems appeals the holding that claims 1 and 6-8 are unpatentable. The CAFC affirmed the Board’s findings as to all claims except claims 15-19, reversing on claim 15 and remanding on dependent claims 16-19.

Background

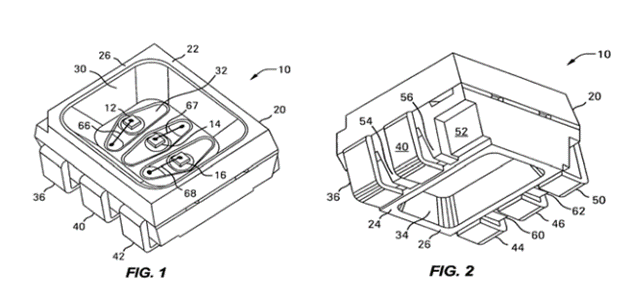

The ‘087 patent relates to an optical device with an LED die, such as for use in a large display panel. As an example, a stadium display may include numerous small light emitting elements arranged in an array and consisting of an LED die mounted to a plastic housing. In an exemplary embodiment, LEDs are mounted in a housing and encapsulated for protection from the environment. The device contains reflector housing 20 with a sidewall 26 extending between top 22 and bottom 24, with a first pocket or cavity 30 formed on top and a second pocket 34 formed on bottom shown in Figs. 1 and 2:

The first pocket 30 may be filled with encapsulant to cover and protect the LED dies. Claim 1 is representative.

1. An optical device comprising:

a lead frame with a plurality of leads;

a reflector housing formed around the lead frame, the reflector housing having a first end face and a second end face and a peripheral sidewall extending between the first end face and the second end face, the reflector housing having a first pocket with a pocket opening in the first end face and a second pocket with a pocket opening in the second end face;

at least one LED die mounted in the first pocket of the reflector housing;

a light transmitting encapsulant disposed in the first pocket and encapsulating the at least one LED die; and

wherein a plurality of lead receiving compartments are formed in the peripheral sidewall of the reflector housing.

The Board found that claims 1 and 6-8 are unpatentable as obvious over Takenaka (teaching most of claim 1) in combination with Kyowa (teaching the remaining limitation requiring multiple lead-receiving compartments in the reflector housing sidewall). The Board further found that Nichia did not demonstrate that claims 1 and 6-14 are unpatentable over Okazaki and Kyowa because Okazaki discloses a tubular vessel instead of the claimed two pockets. The Board found that Document Security’s expert was more credible than Nichia’s expert in that one of ordinary skill would understand Okazaki as teaching a tubular vessel instead of two pockets. The Board also found that Nichia did not demonstrate that claims 9-19 are unpatentable over Takenaka in view of Kyowa because Nichia did not identify disclosure in Takenaka regarding claim 9’s plastic limitation: “A display comprising a plurality of plastic leaded chip carrier LEDs, the plastic leaded chip carrier LEDs each comprising ….” The Board determined that the underlined phrase was not part of the preamble. Lastly, the Board found that Nichia also did not identify any disclosure in Takenaka that teaches or suggests the “electrical connection limitation” in independent claim 15.

Discussion

The CAFC first notes the standard of review: the Board’s legal conclusions are reviewed de novo whereas the factual findings underlying obviousness are reviewed for substantial evidence.

Nichia’s Appeal

Nichia makes three arguments that the Board erred in finding that Nichia failed to show that claims 9-19 are unpatentable over Takenaka in view of Kyowa.

In the first argument, Nichia argued that the Board erred in the construction of the preamble of claim 9. Nichia argued that the preamble should be considered as the entirety of “A display comprising a plurality of plastic leaded chip carrier LEDs, the plastic leaded chip carrier LEDs each” comprising” (the second “comprising” being considered the transitional phrase). The Board found the preamble to be “A display.” Claim construction is an issue of law reviewed de novo. The CAFC simply found that the phrase “[a] display comprising” is a general description followed by the transition word “comprising” and then the required elements.

In the second argument, Nichia argued that the Board abused its discretion by not including information contained in claim charts regarding plastic from Takenaka. The CAFC found that Nichia failed to establish anywhere in its petition or expert declaration that Takenaka disclosed “plastic.” Nichia’s claim charts disclosed use of resin with no argument comparing plastic and resin.

In the third argument, Nichia argued that the Board abused it’s discretion in finding that Nichia did not prove claim 15 unpatentable based on Takenaka in view of Kyowa. Claim 15 is similar to claim 1 but includes the additional limitation of “at least one LED die … electrically connected to said plurality of electrically conductive leads.” Nichia argues that the Board abused its discretion by ignoring Nichia’s reference to its claim chart for claim 1. Unlike with the plastic phrase, Nichia’s petition specifically stated that Takenaka disclosed an electrical connection. Therefore, the CAFC reversed the Board’s determination regarding claim 15 and remanded with respect to dependent claims 16-19.

Document Security’s Cross-Appeal

The cross-appeal challenged the determination that claims 1 and 6-8 are unpatentable over Takenaka in view of Kyowa. Document Security made two arguments. In the first argument, Document Security argued that Takenaka meets all the limitations of the asserted patent’s disclosed method to protect the leads from external forces, and therefore there was no need to combine with Kyowa.[1] Motivation to combine is a finding of fact. The Board relied on Nichia’s expert that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have been motivated to add the compartments described in Kyowa to the LED housing sidewall of Takenaka to protect the leads from external forces. The expert testimony and Kyowa’s disclosure provide “relevant evidence as a reasonable mind” would find supports the Board’s conclusion.

In the second argument, Document Security argued that even if there was motivation to combine, the Board erred because Kyowa does not teach a required element of the claims at issue, arguing that Kyowa does not disclose or suggest reflector housing and therefore cannot teach the lead-receiving compartments limitation. What the prior art teaches is a finding of fact. The Board explained that Kyowa teaches the device is enclosed in a resin package, which is an LED housing, and the sidewall contains multiple compartments in the housing. The Board reasoned that since Takenaka teaches a housing formed of white resin having high reflectance, it would correspond to the required reflector housing. As such, the CAFC found the Board’s findings supported by substantial evidence.

Takeaways

- Any IPR petition needs to clearly tie elements of the prior art to elements of the claim(s) at issue. For example, the resin of the prior art needed to be shown to correspond to plastic of claim 9. On the other hand, Nichia’s petition clearly set forth “electrical” connection which resulted in reversal.

[1] The author notes that this seems to be strange that the patent owner was arguing that it’s claim would be taught by one prior art reference. It is suspected that the strategy was to save the claim based on the multiple compartments limitation which was taught by the secondary reference.

Insufficient Extrinsic Evidence and Prosecution Disclaimer Led to Claim Construction in Patentee’s Favor

| May 6, 2022

Decided: April 1, 2022

Newman, Reyna, and Stoll. Opinion by Reyna.

Summary

The CAFC found in favor of a patentee seeking broad interpretation of a claim term, where an expert testimony offered by an opponent in support of narrower claim scope was insufficient to overcome a clear record of the patent, and the prosecution history lacked “clear and unmistakable” statements to establish express disavowal of claim scope.

Details

This is an appeal from a district court action where Genuine Enabling Technology LLC (“Genuine”) sued Nintendo Co., Ltd. and Nintendo of America, Inc. (“Nintendo”) for infringing certain claims of U.S. Patent No. 6,219,730. The patent relates to user input devices, such as mouse and keyboard, and its representative claim 1 recites:

1. A user input apparatus operatively coupled to a computer via a communication means additionally receiving at least one input signal, comprising:

user input means for producing a user input stream;

input means for producing the at least one input signal;

converting means for receiving the at least one input signal and producing therefrom an input stream; and

encoding means for synchronizing the user input stream with the input stream and encoding the same into a combined data stream transferable by the communication means.

(Emphasis added.)

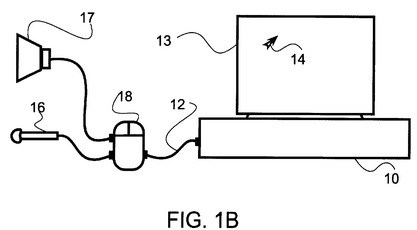

The inventive idea may be pictured as a “voice mouse.” As seen in Fig. 1B of the patent, the inventive apparatus or mouse 18, connected with a computer 10 via a communication link 12, serves the traditional function of allowing user to move an object 14 on the computer monitor 13 (i.e., “user input means for producing a user input stream”), while also capable of receiving a speech input from a microphone 16 (i.e., “input means for producing the at least one input signal”) and transmitting a speech output to a speaker 17.

At issue in the case is the construction of the term “input signal.”

During prosecution, the inventor distinguished his invention over U.S. Patent No. 5,990,866 (“Yollin”) cited in an office action, arguing that the “input signal” limitation was missing in the reference. Specifically, the inventor argued that various physiological sensors disclosed in Yollin, such as those detecting user’s muscle movement, heart rate, brain activity, blood pressure, skin temperature, etc., only produce “slow varying” signals as opposed to “signals containing audio or higher frequencies” to which his invention pertains. The inventor pointed out that the inventive apparatus would resolve a specific problem presented by the use of high frequency signals, which, unlike slow varying signals, tend to “collide” with other signals in producing a composite data stream. This “slow varying” vs. “audio or higher frequencies” distinction is repeatedly noted in the inventor’s argument.

The parties disputed the extent of prosecution disclaimer resulting from the inventor’s statements as to the term “input signal.” In the district court, Genuine proposed to construe the term as

“a signal having an audio or higher frequency,”

whereas Nintendo maintained that the proper scope should be narrower:

“A signal containing audio or higher frequencies. [The inventor] disclaimed signals that are 500 Hertz (Hz) or less. He also disclaimed signals that are generated from positional change information, user selection information, physiological response information, and other slow-varying information. Alternatively, indefinite.”

Nintendo argued that the inventor disclaimed the certain types of “slow-varying” signals taught by Yollin. While specific frequencies were not disclosed in Yollin, Nintendo relied on its expert testimony citing a reference purportedly showing that Yollin’s physiological sensors encompassed the range of “at least 500 Hz.”

Genuine contended that the disclaimed scope should be limited to “slow-varying signals below the audio frequency spectrum [of 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz],” in accordance with the inventor’s argument which only had distinguished the reference “slow-varying” signals from “fast-varying” signals.

The district court sided with Nintendo, finding non-infringement in its favor. In particular, the district court noted that “an applicant’s argument that a prior art reference is distinguishable on a particular ground can serve as a disclaimer of claim scope even if the applicant distinguishes the reference on other grounds as well.” Andersen Corp. v. Fiber Composites, LLC, 474 F.3d 1361, 1374 (Fed. Cir. 2007). That is, according to the district court, the fact that the inventor’s argument distinguished Yollin as lacking “audio or higher frequencies” did not negate the effect of the inventor’s statement also distinguishing Yollin’s range as “slow-varying” signals.

On appeal, the CAFC rejected the district court’s claim construction.

First, the CAFC noted that the role of extrinsic evidence in claim construction is limited, and cannot override intrinsic evidence where there is clear written record of the patent. And as one form of extrinsic evidence, “expert testimony may not be used to diverge significantly from the intrinsic record.” Here, the 500 Hz frequency threshold was not identified in the intrinsic record nor Yollin, and its only basis was Nintendo’s expert testimony which relied on another extrinsic reference that was not in the record. The extrinsic evidence conflicted with the prosecution history in which the examiner had accepted the inventor’s argument distinguishing Yollin without drawing a bright line between “slow-varying” and “audio or higher frequenc[y]” signals. As such, the CAFC found that the expert testimony cannot overcome the clarity of the intrinsic evidence.

Second, the CAFC noted that prosecution disclaimer requires that the patentee make a “clear and unmistakable” statement to disavow claim scope during prosecution. The fact that the inventor repeatedly distinguished the reference “slow-varying” signals from “audio or higher frequenc[y]” signals—the argument which successfully traversed the rejection—led the CAFC to decide that the “clear and unmistakable” disavowal was limited to “signals below the audio frequency spectrum.” Although the CAFC noted that the inventor’s statements “may implicate” certain frequency ranges such as 500 Hz or less, the intrinsic record was not unambiguous enough for the particular range to be disclaimed. For similar reasons, the CAFC also found no disclaimer of “signals that are generated from positional change information, user selection information, physiological response information, and other slow-varying information,” which had not been directly addressed in the inventor’s argument.

The CAFC concluded that the district court erred in the claim construction and that the proper scope of the term “input signal” is “a signal having an audio or higher frequency.”

Takeaway

This case provides a reminder that caution should be taken not to make “clear and unmistakable” statements in arguing around the prior art during prosecution. Although there appears to be no fixed criteria for assessing what qualifies as a “clear and unmistakable” disavowal, applicant’s consistency in presenting one main argument—focused on an essential distinction between the claim and the prior art—without introducing unnecessary details may help limit the extent of potential prosecution disclaimer.